Abstract

Extracellular phosphate (Pi) can act as a signaling molecule that directly alters gene expression and cellular physiology. The ability of cells or organisms to detect changes in extracellular Pi levels implies the existence of a Pi-sensing mechanism that signals to the body or individual cell. However, unlike in prokaryotes, yeasts, and plants, the molecular players involved in Pi sensing in mammals remain unknown. In this study, we investigated the involvement of the high-affinity, sodium-dependent Pi transporters PiT1 and PiT2 in mediating Pi signaling in skeletal cells. We found that deletion of PiT1 or PiT2 blunted the Pi-dependent ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation and subsequent gene up-regulation of the mineralization inhibitors matrix Gla protein and osteopontin. This result suggested that both PiTs are necessary for Pi signaling. Moreover, the ERK1/2 phosphorylation could be rescued by overexpressing Pi transport–deficient PiT mutants. Using cross-linking and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer approaches, we found that PiT1 and PiT2 form high-abundance homodimers and Pi-regulated low-abundance heterodimers. Interestingly, in the absence of sodium-dependent Pi transport activity, the PiT1-PiT2 heterodimerization was still regulated by extracellular Pi levels. Of note, when two putative Pi-binding residues, Ser-128 (in PiT1) and Ser-113 (in PiT2), were substituted with alanine, the PiT1-PiT2 heterodimerization was no longer regulated by extracellular Pi. These observations suggested that Pi binding rather than Pi uptake may be the key factor in mediating Pi signaling through the PiT proteins. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Pi-regulated PiT1-PiT2 heterodimerization mediates Pi sensing independently of Pi uptake.

Keywords: bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), bone, cartilage, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK), signaling, PiT1, PiT2, membrane transporters, phosphate sensing

Introduction

Phosphorus is the sixth most abundant element in the human body, constituting ∼1% of total body weight (1). About 85% of total phosphate can be found in the skeleton, where it is a major constituent of hydroxyapatite crystals deposited on the extracellular organic matrix during the mineralization process. The remaining 15% is found mainly in cells from soft tissues and in extracellular volume, where it represents <1% of total phosphate (2–4). In plasma, ∼16% of circulating phosphate is found as organic phosphate bound to proteins and lipids, whereas the major part (84%) is orthophosphate, or free inorganic phosphate (Pi),5 that can be filtered by the kidney (1). At physiological pH, the monovalent H2PO4− and the divalent HPO42− forms are present at a 1:4 molar ratio (5). Although this plasma Pi represents a small fraction of total body phosphorus, it serves as an exchange pool between the various Pi-containing and -regulating organs, and disturbances in Pi homeostasis can affect almost all organ systems.

In addition to the widespread structural and metabolic functions of Pi, it has become increasingly apparent during the past 15 years that extracellular Pi can act as a signaling molecule directly altering gene expression and cell phenotype (6–9). The abundance of Pi in the skeleton has led to early studies describing the effects of extracellular Pi in this organ. Exposing cultured chondrocytes to a high level of extracellular Pi leads to their terminal maturation and subsequent matrix mineralization (10–13). Similarly, the apoptosis of terminally differentiated hypertrophic chondrocytes was shown to be dependent upon the circulating plasma Pi levels in vivo (14). In both of these in vitro and in vivo approaches, the Pi-mediated apoptosis of chondrocytes was dependent upon the activation of the MAPK ERK1/2 pathway (15–17), but not of other mitogen-activated protein kinases, such as p38 or c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Interestingly, the Pi-dependent activation of the ERK1/2 pathway up-regulated the gene expression of the mineralization inhibitors matrix Gla protein (Mgp) and osteopontin (Opn), most likely setting off a feedback mechanism to control Pi-induced mineralization (7, 16, 18, 19). The elevated extracellular Pi level was also shown to be important in osteoblast proliferation and differentiation (16, 20–24), cementoblast formation (25), odontoblast differentiation (26, 27), and osteoclast differentiation (28–30).

The Pi-mediated signaling underlies the notion that cells must possess a Pi-sensing mechanism on the surface of or within the cell that is able to detect and respond to the variation of extracellular Pi levels. The ability of organisms to detect changes in extracellular levels of other metabolites (such as Ca2+, glucose, or amino acids) has already been described (31–33), and emerging evidence suggests that similar events are at work to mediate the cellular effects of Pi (8, 34–36). Although the identity of the molecules involved in these mechanisms is still unknown in mammals, Pi-sensing machineries have been characterized in prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms (37). In Escherichia coli, the phosphate transporter PstS and other periplasmic proteins (PstC, Pst, and PstB/PhoU) detect the variation of external Pi concentrations. In case of a low extracellular Pi level, this system increases the efficiency of Pi retention in the bacteria (38). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a low extracellular Pi level resulted in induction of the Pi transporter Pho84, now identified as the essential component of the Pi-sensing system (38, 39). Interestingly, following Pi restriction, it was demonstrated that Pho84 could trigger the rapid activation of protein kinase A without transporting Pi (40).

In mammals, the Slc20a1/PiT1 and Slc20a2/PiT2 proteins are expressed at the plasma membrane and have been described as mediating the intracellular uptake of Pi with a high affinity (41–43). PiT1 and PiT2 have a wide tissue distribution, being the only Pi transporters expressed in bone (44, 45). Interestingly, their expression can be modulated by extracellular Pi (21, 43, 44, 46, 47), and previous studies have suggested that they can mediate downstream effects of extracellular Pi. In bone, the elegant study of Kimata et al. (48) suggests that the chondrocyte response to extracellular Pi is mediated by a PiT1-dependent up-regulation of cyclin D1 through ERK1/2 pathway activation. The authors hypothesize that Pi-driven conformational changes of PiT1 could be involved in the Pi-sensing mechanism. In parathyroid cells, PiT1 was suggested to act as a Pi sensor to modulate the secretion of the phosphaturic parathyroid hormone (49). On the other hand, based on its property of oligomerizing upon extracellular Pi variation, PiT2 was also proposed to serve as a Pi sensor (50). Although these data support a possible role for PiT1 or PiT2 as Pi sensors, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. Because PiT1 and PiT2 have very close Pi transport characteristics (51), they may also share Pi-sensing properties and thus have interconnected roles in Pi sensing. Moreover, because Pi-independent functions have been highlighted recently for PiT1 (52–56), the involvement of Pi transport in the Pi sensing by PiT1 or PiT2 remains to be investigated.

In this report, we investigated the role of PiT1 and PiT2 as Pi sensors in osteoblastic and chondrocytic cell lines. We show that both PiT1 and PiT2 are required for mediating Pi-dependent signaling. We demonstrate that PiT1 and PiT2 could interact together and that extracellular Pi modulates this interaction. Finally, we show that cellular Pi uptake is not required to mediate Pi signaling through the PiT proteins.

Results

Requirement of both PiT1 and PiT2 for Pi-mediated signaling

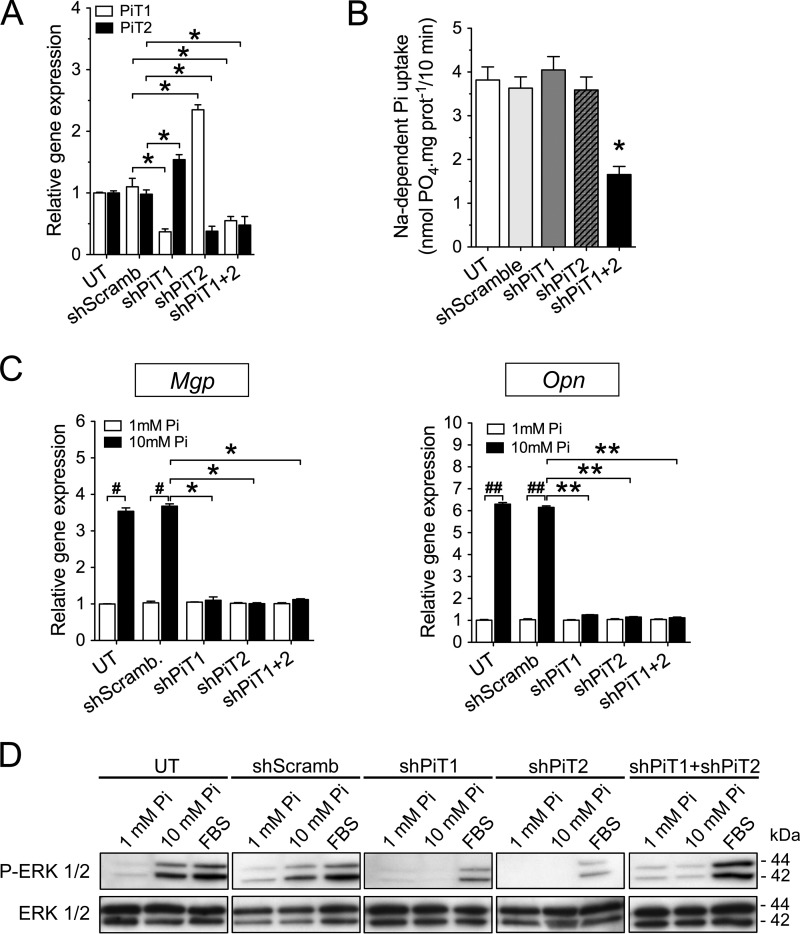

We first investigated whether PiT1 and/or PiT2 were involved in the Pi-dependent up-regulation of Mgp and Opn expression. To this aim, using RNA interference, we established stably transfected osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 clones in which PiT1 or PiT2 expression was knocked down. In MC3T3-E1 shPiT1 clones, PiT1 gene expression showed a 63% reduction, together with a significant up-regulation of PiT2 (Fig. 1A). Similarly, the MC3T3-E1 shPiT2 clones displayed a 62% decrease in PiT2 mRNA level, together with a significant up-regulation of PiT1 (Fig. 1A). Comparable results were observed when cells were incubated with 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration (Fig. S1A). Interestingly, the sodium-dependent Pi uptake was similar in MC3T3-E1 shPiT1 and shPiT2 clones and control MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 1B), suggesting that a depletion of either PiT may be compensated by the remaining PiT, as was previously suggested (56). Consistent with this possibility, MC3T3-E1 clones stably transfected with both shPiT1 and shPiT2 resulted in a 52% reduction of both PiTs (Fig. 1A), resulting in a similar decrease in sodium-dependent Pi uptake (Fig. 1B). In contrast to wildtype differentiated MC3T3-E1 cells in which Mgp and Opn expression was up-regulated following stimulation with 10 mm extracellular Pi for 24 h, the up-regulation of Mgp and Opn expression in PiT-depleted MC3T3-E1 clones was blunted (Fig. 1C). The defect in Pi-dependent Mgp and Opn up-regulation arose despite a normal Pi transport in the shPiT1 or shPiT2 MC3T3-E1 clones, suggesting that a variation in intracellular Pi content is unlikely to account for defects in Pi-dependent signaling in the absence of either PiTs. Because the ERK1/2 signaling pathway was shown to be required for Pi-dependent regulation of Mgp and Opn expression (16, 19), we investigated the Pi-dependent ERK1/2 activation in differentiated PiT-depleted MC3T3-E1 clones. We showed that following a 30-min (Fig. S1B) or 24-h (Fig. 1D) stimulation with 10 mm extracellular Pi, the activation of ERK1/2 pathway was blunted in shPiT1, shPiT2, or shPiT1/shPiT2 clones, as compared with untransfected and shScramble-transfected cells. Similar data were obtained in three separate PiT-depleted MC3T3-E1 clones (Fig. S1, B–D) and in transiently transfected MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. S2). Interestingly, the effect of PiT depletion on the activation of ERK1/2 pathway following stimulation with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was not as pronounced as Pi stimulation, arguing for a specificity of PiT1 and PiT2 in the Pi-dependent activation of the ERK1/2 pathway.

Figure 1.

Pi-dependent Mgp and Opn gene regulation and ERK1/2 signaling require both PiT1 and PiT2 in MC3T3-E1 cells. A, RT-qPCR analysis of PiT1 (white bars) and PiT2 (black bars) mRNA levels in untransfected (UT) or stably transfected MC3T3-E1 cells, as indicated. Data are means ± S.E. (*, versus shScramb, p < 0.05, n = 3). B, sodium-dependent Pi uptake was measured in untransfected or stably transfected MC3T3-E1 cells, as indicated. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3). C, RT-qPCR analysis of Mgp and Opn mRNA levels in untransfected or stably transfected MC3T3-E1 cells, as indicated. Cells were incubated in low-serum (0.5%) medium for 24 h and stimulated with 1 mm (white bars) or 10 mm (black bars) extracellular Pi concentration for 24 h. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (#, p < 0.05; ##, p < 0.01 versus 1 mm Pi control; and *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus shScramb; n = 3) D, Western blot analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (P-ERK 1/2) in untransfected or stably transfected MC3T3-E1 cells, as indicated. Cells were incubated in low-serum (0.5%) medium for 24 h and stimulated for another 24 h with 1 mm or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration or with 10% FBS used as a positive control for ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Total ERK1/2 proteins were used as a loading control.

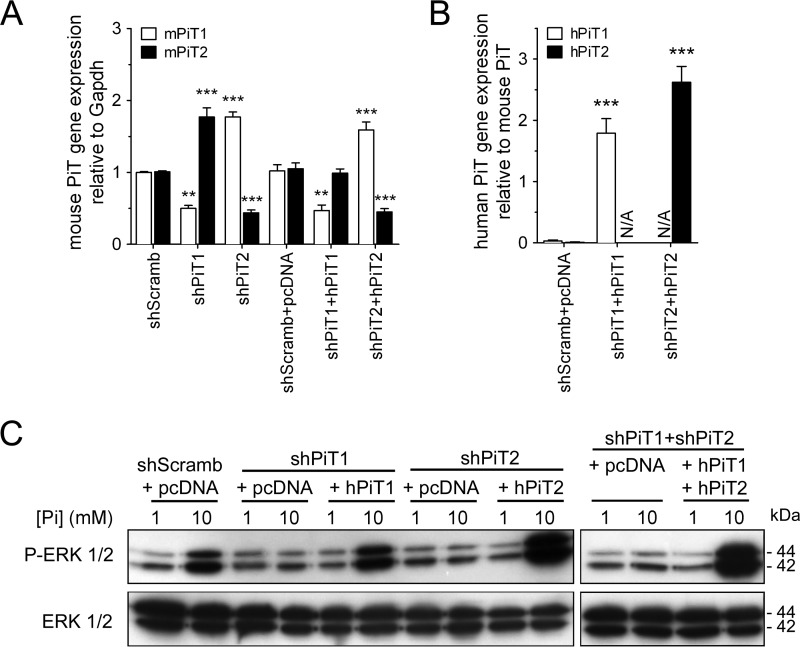

Moreover, we performed similar experiments in the MC615 chondrogenic cell line. We used a transient transfection approach leading to a 50 and 56% deletion of PiT1 and PiT2 mRNA levels, respectively (Fig. 2A). A similar extent of PiT deletion was obtained at the protein level, as shown by immunofluorescence (Fig. S3). MC615 cells were also used to rescue PiT deletion by overexpressing human PiT1 and PiT2 in PiT1- and PiT2-depleted cells, respectively (Fig. 2B). Similar to what was observed in MC3T3-E1 cells, depletion of either PiT1 or PiT2 in MC615 cells blunted the activation of the ERK1/2 pathway by 10 mm extracellular Pi, despite the up-regulation of the remaining PiT (Fig. 2C). When human PiT1 was overexpressed in PiT1-depleted MC615 cells, we could rescue the Pi-dependent ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained when human PiT2 was overexpressed in PiT2-depleted MC615 cells or when both human PiT1 and PiT2 were overexpressed in PiT1-PiT2–depleted MC615 cells (Fig. 2C). This further illustrated the requirement of both PiT1 and PiT2 for the Pi-dependent ERK signaling in cell lines of skeletal origin.

Figure 2.

Pi-dependent ERK1/2 signaling requires both PiT1 and PiT2 in MC615 cells. A, RT-qPCR analysis of mPiT1 (white bars) and mPiT2 (black bars) mRNA levels in transiently transfected MC615 cells, as indicated. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus shScramb; n = 3). B, RT-qPCR analysis of hPiT1 (white bars) and hPiT2 (black bars) mRNA levels in transiently transfected MC615 cells, as indicated. The endogenous murine PiT1 or PiT2 genes were used as reference genes to evaluate the overexpression of the transfected human PiT genes. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (***, p < 0.001 versus shScramb+pcDNA, n = 3). N/A, not applicable. C, Western blot analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (P-ERK 1/2) in transiently transfected MC615 cells, as indicated. Cells were incubated in low-serum (0.5%) medium for 24 h and stimulated for 30 min with 1 mm or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration as indicated. Total ERK1/2 proteins were used as a loading control.

PiT1 and PiT2 form hetero-oligomers upon variation of extracellular Pi concentrations

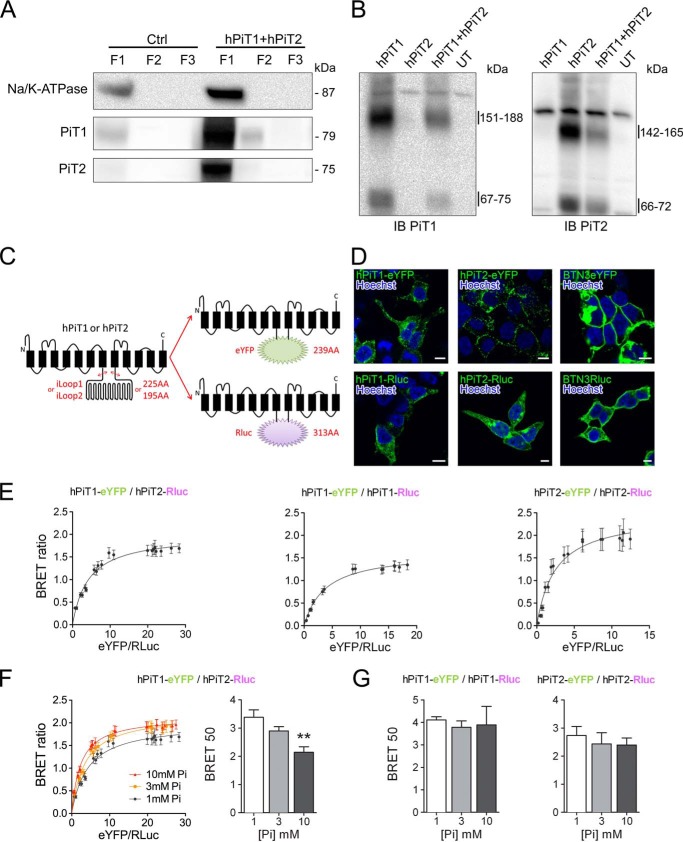

The requirement of both PiT1 and PiT2 for Pi-dependent ERK1/2 signaling may indicate the existence of a functional protein complex comprising both PiTs. This possibility is also reinforced by the presence in PiT1 and PiT2 protein sequences of a conserved and highly hydrophobic 127-amino acid domain that was suggested to be important for determining the quaternary structure of the protein (57). To investigate the formation of hetero- and homo-oligomers, we used HEK293T cells that are easy to transfect, allow a robust expression of PiTs at the plasma membrane, and have been shown to have similar Pi-mediated ERK1/2-specific activation (58). In addition, because PiT proteins are often difficult to detect using total cell extracts in Western blot experiments, we used a crude cell fractionation approach to analyze an enriched plasma membrane protein fraction revealed by the specific expression of the Na/K-ATPase, as shown in Fig. 3A. When analyzing the enriched plasma membrane fraction from PiT1- and/or PiT2-transfected cells by Western blotting, we could observe protein complexes after cell surface cross-linking using BS3, a membrane-impermeable cross-linker (Fig. 3B). The apparent molecular mass of 142–165 kDa that we detected from cells transfected with hPiT2 alone recapitulated the results obtained by Salaün et al. (50) demonstrating the formation of PiT2 homodimers. Similarly, the 151–188 kDa apparent molecular mass band detected from cells transfected with hPiT1 is consistent with the association of two PiT1 molecules. When cells were co-transfected with both hPiT1 and hPiT2, no change was observed in the band profile, apart from a less intense signal due to transfection with 50% fewer hPiT1 or hPiT2 plasmids. In this condition, we could not detect a distinct band at the theoretical PiT1-PiT2 heterodimer molecular mass, most likely due to the expected similar molecular weights of PiT homo- and heterodimers.

Figure 3.

Specific interaction between PiT1 and PiT2 varies upon extracellular Pi concentration. A, Western blotting analysis of Na/K-ATPase, hPiT1, and hPiT2 expression in pmaxGFP-transfected (Ctrl) or hPiT1 and hPiT2 co-transfected HEK293T cells after crude cellular fractionation, as indicated (see “Experimental procedures” for details). Overexpression of hPiT1 and PiT2 allowed a better signal than Ctrl. B, Western blotting analysis (IB) of hPiT1 (left) and hPiT2 (right) expression in HEK293T cells untransfected (UT) or transfected with hPiT1, hPiT2, or both after cell surface cross-linking using bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate and cellular fractionation. Enriched plasma membrane fraction (F1) was analyzed. C, schematic representation of chimeric hPiT1-eYFP or -Rluc and hPiT2-eYFP or -Rluc proteins used for BRET assays. The DNA region encoding for the large internal loop of PiT1 and PiT2 (iLoop1 and iLoop2, respectively) was replaced by coding sequences of eYFP or Rluc. Transmembrane domains (black rectangles) are shown. D, confocal images obtained from transfected HEK293T cells, as indicated. Rluc was detected after immunofluorescence and nuclei were stained using Hoechst (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. E, representative BRET saturation curves of co-transfected HEK293T cells, as indicated. F, representative BRET saturation curves (left panel) and BRET 50 index (right panel) of HEK293T co-transfected with hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc obtained following a 10-min incubation with 1, 3, or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration, as indicated. BRET 50 data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (**, p < 0.01 versus 1 mm Pi condition, n = 8). G, the BRET 50 index was measured from BRET saturation curves obtained from HEK293T co-transfected with hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT1-Rluc (left) or hPiT2-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc (right) following a 10-min incubation with 1, 3, or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration. BRET 50 data are means ± S.E., and no statistically difference was observed (n = 4–8).

To study further the PiT oligomerization, we then used a BRET approach. To this aim, we constructed hPiT1 and hPiT2 chimeric proteins expressing the eYFP acceptor or Rluc donor. Because structure-function studies have excluded a role of the large intracellular loop (iLoop) in Pi transport and retrovirus binding (59–62) and showed no overlapping between iLoop and the highly hydrophobic domain (57), we substituted the iLoop with eYFP and Rluc sequences (Fig. 3C). When expressed in HEK293T, the chimeric hPiT1-eYFP or -Rluc and hPiT2-eYFP or -Rluc proteins could be visualized at the plasma membrane, as shown by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3D), enabling us to study their role in detecting the variation of extracellular Pi levels. We performed saturation BRET experiments in living cells to investigate their potential hetero- and homo-oligomerization. As shown in Fig. 3E, we obtained typical BRET-saturable curves when using hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc proteins, together with a high BRET ratio. In contrast, when the BTN3A2 protein was used instead of either PiT, no saturation could be achieved, together with a weak BRET ratio (Fig. S4, A and B). These data support the notion that PiTs can form hetero- and homo-oligomers specifically. We confirmed the specificity of the hetero-oligomers by a competition assay (Fig. S4C) whereby overexpression of untagged PiT1 or PiT2 reduces the BRET ratio, whereas unrelated BTN3A2 expression does not. We next determined whether the interaction of PiTs could be modulated by the variation of extracellular Pi concentration. We therefore performed the same saturation BRET experiments after a 10-min stimulation with 1, 3, or 10 mm extracellular Pi. Results reported in Fig. 3 (F and G) and Fig. S5A showed that saturation curves were different upon extracellular Pi concentration only for hPiT1-hPiT2 hetero-oligomers. Indeed, calculating the BRET 50 values from these curves, we showed a significant decrease at 10 mm extracellular Pi, suggesting a stronger interaction between PiT1 and PiT2 in this condition, whereas no variation was observed for homo-oligomers. In all conditions, the BRET max values did not vary significantly (Fig. S5B).

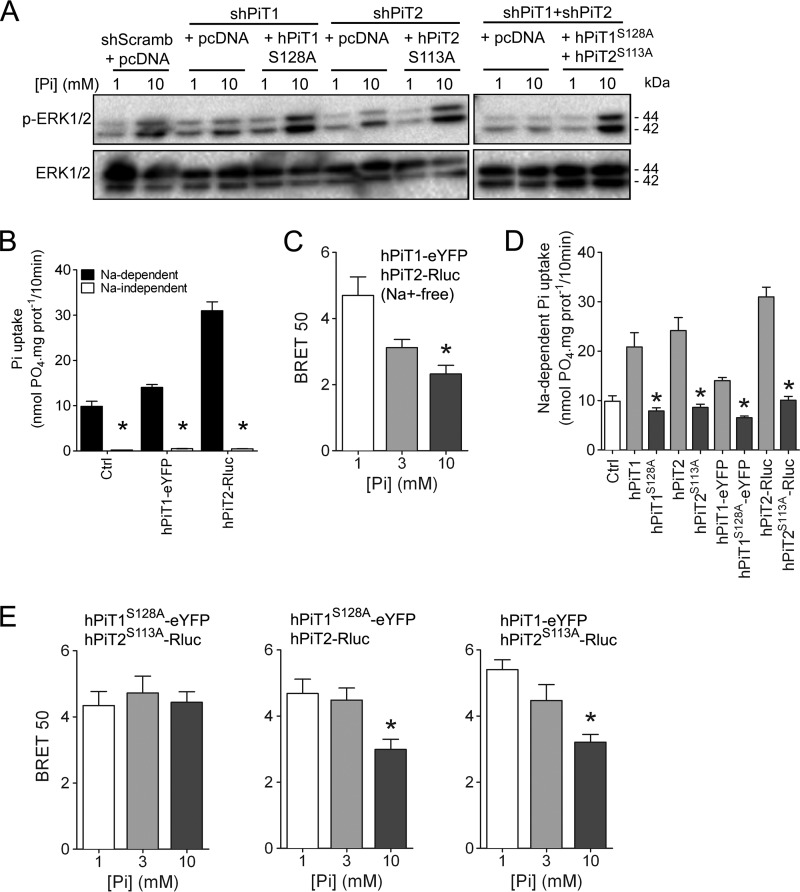

PiT1-PiT2–mediated ERK1/2 activation by extracellular Pi and regulation of PiT hetero-oligomerization are Pi transport–independent

Our results illustrated that both PiT proteins are important for Pi-dependent ERK signaling and that Pi can modulate PiT hetero-oligomerization. To elucidate whether the Pi transport function of PiTs was important to mediate Pi-dependent ERK1/2 signaling, we used the previously reported hPiT1S128A and hPiT2S113A Pi transport–deficient mutants (56, 63, 64). When hPiT1S128A was overexpressed in PiT1-depleted cells in which Pi-dependent ERK1/2 activation was lost, we could rescue the activation of ERK1/2 signaling (Fig. 4A). Similarly, we could rescue the Pi-dependent ERK1/2 activation in PiT2-depleted cells by overexpressing hPiT2S113A mutant. This was also true when cells depleted from both PiTs were transfected by both hPiT1S128A and hPiT2S113A (Fig. 4A). These data demonstrated that the Pi transport function of PiTs was dispensable for the Pi-dependent ERK1/2 activation. To further study whether the sodium-dependent Pi transport function of PiTs was important to mediate Pi-dependent PiT hetero-oligomerization, we performed BRET experiments in the absence of Na+. In this condition where Pi transport was blunted, the variation of extracellular Pi concentrations was still able to modulate PiT interaction (Fig. 4 (B and C) and Fig. S5C). Because Pi was able to modulate PiT interaction without being transported, this suggests that the binding of Pi to PiT proteins rather than its actual uptake into the cell may be involved in the modulation of PiT interaction. We next generated mutated versions of the chimeric hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc proteins in which Ser128 or Ser113 was replaced by an alanine residue. As expected, overexpression of chimeric hPiT1S128A-eYFP and hPiT2S113A-Rluc resulted in decreased sodium-dependent Pi transport compared with transporting chimeric PiT proteins (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, using a BRET approach, we showed that although hPiT1S128A-eYFP and hPiT2S113A-Rluc were still able to interact together, this interaction was not modulated anymore by extracellular Pi variations (Fig. 4E (left) and Fig. S5C), consistent with a role for Ser128 or Ser113 in Pi binding. When BRET experiments were performed with a transport-deficient mutant (hPiT1S128A-eYFP or hPiT2S113A-Rluc) and a transporting chimeric PiT protein (hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc), we could recover the modulation of PiT interaction by Pi (Fig. 4E (middle and left) and Fig. S5C), further supporting a role of Ser128 or Ser113 in the Pi-dependent interaction of PiTs.

Figure 4.

Pi-dependent ERK1/2 signaling and PiT1-PiT2 hetero-oligomerization are independent of Pi transport. A, Western blot analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation (P-ERK 1/2) in transiently transfected MC615 cells, as indicated. Overexpression of Pi transport–deficient hPiT1 (PiT1S128A) and/or hPiT2 (PiT2S113A) was performed in PiT1–, PiT2–, or PiT1-PiT2–depleted cells, respectively. Cells were incubated in low-serum (0.5%) medium for 24 h and stimulated for 30 min with 1 or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration. Total ERK1/2 proteins were used as a loading control. B, sodium-dependent and -independent Pi uptake was measured in HEK293T cells transfected as indicated. Data are means ± S.E. (error bars) (*, p < 0.05 versus sodium-dependent, n = 4). C, BRET 50 index was measured from BRET saturation curves obtained after a 10-min stimulation with 1, 3, or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration from HEK293T co-transfected with hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc in an Na+-free medium. Data are means ± S.E. (*, p < 0.05 versus 1 mm Pi condition, n = 4). D, sodium-dependent Pi uptake was measured in HEK293T cells transfected with pcDNA6A plasmid (Ctrl) or with plasmids containing normal (hPiT1 and hPiT2) or Pi transport–deficient mutants (hPiT1S128A and hPiT2S113A) with or without BRET chimeric acceptor or donor, as indicated. Data are means ± S.E. (*, p < 0.05 versus Pi-transporting PiTs, n = 4). E, BRET 50 index was measured from BRET saturation curves obtained after 1, 3, or 10 mm extracellular Pi concentration stimulation for 10 min from HEK293T co-transfected with the indicated plasmids. Data are means ± S.E. (*, p < 0.05 versus 1 mm Pi condition, n = 4–5).

Discussion

The ability of a cell to detect changes in extracellular Pi levels is paramount for its adequate response to environmental fluctuations and critical for the appropriate modulation of Pi homeostasis and skeletal mineralization. In this work, we provided mechanistic insights into the molecular events leading to the detection of changes in extracellular Pi concentrations using skeletal cell lines as a model.

Skeletal cells are constantly exposed to high local extracellular Pi levels, mainly due to the continual resorption and formation of the mineralized extracellular matrix of bone and the need for tremendous quantities of Pi for mineralization purposes (65). This has made bone a model of choice to study Pi signaling, where it has been shown in early studies to regulate the programmed cell death of hypertrophic chondrocytes (10, 11, 13). In subsequent studies, we and others have shown that Pi could regulate skeletal mineralization by controlling the expression of the mineralization inhibitors Mgp and Opn through the activation of the ERK1/2 pathway (7, 15, 16, 18, 19). Our present study brings evidence for a role of PiT1 and PiT2 in transmitting the Pi signal to the cell by showing that the Pi-dependent up-regulation of Mgp and Opn and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were blunted in PiT1- or PiT2-depleted cells. A role for PiT1 in mediating ERK1/2 signaling has been reported earlier (48, 55); however, a similar role for PiT2 has never been illustrated before.

A critical aspect in studying the molecular events involved in Pi signaling is whether or not Pi needs to be transported within the cell to fulfill its role. This question is particularly relevant in view of the role of PiT1 and PiT2 as mediators of Pi signaling because these two proteins have well-described Pi transport functions (41–43). By using Pi transport–deficient mutants of PiT proteins, we could rescue the ERK1/2 signaling, demonstrating that PiT1 and PiT2 can mediate a Pi signal without transporting the ion. Furthermore, the loss of ERK1/2 signaling in the absence of PiT1 or PiT2 was not associated with a change in cellular Pi uptake, further indicating that the transport of Pi into the cell is not necessary for Pi signaling.

These data have major implications for the understanding of the Pi-signaling mechanism. The absence of functional compensation by PiT1 in PiT2-depleted cells, and vice versa, together with the requirement of both PiTs for Pi signaling, suggested that they could interact functionally and/or physically to mediate the Pi signal. Consistent with this hypothesis, using a BRET approach, we showed that PiT proteins could form homo- and heterodimers. More strikingly, we could illustrate that the formation of PiT1-PiT2 heterodimers only was affected by the variation of extracellular Pi levels. We could not quantify the relative importance of hetero- versus homodimers, but the cross-linking data supported the idea that the Pi-sensitive PiT1-PiT2 heterodimers were present at much lower quantities. It is possible that a low-abundance Pi-sensitive PiT1-PiT2 heterodimer may be more effectively tunable than a highly abundant Pi sensor. This abundance may also be consistent with the on/off Pi effect on ERK1/2 signaling that we have observed when deleting the PiT proteins.

Although a Pi-sensitive PiT1-PiT2 heterodimer is likely to represent an important component of the Pi-sensing machinery, deciphering the detailed functioning of such a sensor requires additional work. Nevertheless, our data provide several important mechanistic insights that may give clues to the understanding of the Pi-signaling cascade. We showed that in the absence of Na+, which blunts the Pi transport activity of PiT proteins, the formation of PiT1-PiT2 heterodimers was still sensitive to extracellular Pi variations. This is consistent with the idea that binding of Pi, rather than transport itself, is important for PiT1-PiT2 heterodimerization. This also suggests that Ser128 and Ser113 residues that were demonstrated to be critical for Pi transport by PiT1 and PiT2 (56, 63) may indeed be involved in Pi binding, a prerequisite step for Pi transport (51). In line with this possibility, when BRET experiments were performed using PiT1 and PiT2 chimeric proteins in which Ser128 and Ser113 were substituted with alanine residues, the PiT1-PiT2 heterodimer was not responsive anymore at extracellular Pi variations. The substitution of only one serine, however, rescued Pi sensitivity of the PiT1-PiT2 heteroduplex, illustrating the complex relationship between the structural arrangement of the Pi binding site and Pi sensitivity. A determination of the crystal structure of PiT proteins is therefore necessary to help determine the identity of the Pi binding site and its role in Pi transport and sensing.

An interesting consequence of our work is that PiT proteins should not be considered anymore as Pi transporters solely but also as Pi receptors able to mediate Pi signaling by activating specific downstream pathways. Such a hybrid transporter-receptor behavior may indicate that the PiT1-PiT2 heteroduplex could behave as a Pi transceptor, whereby conformational changes during the transport cycle (including the Pi-binding step) affect a signal transduction component that triggers a downstream signaling pathway (66). The difference between a transceptor and a pure receptor is that the transceptor can also transport the ligand into the cell. In recent years, evidence for transporters functioning as transceptors has been obtained in several eukaryotic systems (67). Interestingly, in yeast, the Pho84 phosphate carrier that is considered as an essential component of the Pi-sensing system was characterized as a Pi transceptor (40). In prokaryotic or lower eukaryotic organisms, true transceptors could be functionally characterized by specific mutants that either lack the signaling capacity and retain normal transport or have lost transport but retain signaling. In the case of PiT proteins, the signaling capacity is lost when either PiT1 or PiT2 is deleted, indicating that the possible transceptor function may only be revealed by heterodimerization and may not be associated with structural changes of either PiT. The gain of function provided through PiT heterodimerization implies that a unique protein complex mediates Pi signaling. This underlies the idea that specific PiT1 and PiT2 protein partners may be involved in this process. If this is the case, the identification of PiT-specific partners in the future may provide unique targets to modulate Pi signaling in specific organs or specific physiological conditions.

In summary, this study provided mechanistic insights into the Pi-signaling cascade in skeletal cell line models by unraveling PiT1-PiT2 heterodimers as essential components of a Pi-sensing machinery. Although in vivo studies are required to strengthen the physiological relevance of these findings, our work may help in deciphering the mechanisms underlying the ability of the organism to respond to the serum Pi level variations, which is the necessary first step in the Pi homeostasis-regulating cascade.

Experimental procedures

Cells and culture conditions

Murine preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded at 104 cells/cm2 and cultured for 10 days in α-minimum essential medium GlutaMAXTM (catalogue no. 32751, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Saint-Aubin, France) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Murine chondrogenic MC615 cells were seeded at 104 cells/cm2 and maintained in a medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) high glucose GlutaMAXTM/Ham's F-12 (1:1) (catalogue no. 31966 and 31765, respectively, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HEK293T cells were maintained in DMEM high glucose GlutaMAXTM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mm HEPES, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air, and media were renewed every 2–3 days. When indicated, cells were incubated in low-serum (0.5%) medium for 24 h and stimulated with various concentrations of Pi for 30 min or 24 h. Pi was added as a mixture of NaH2PO4 and Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4), as described previously (10).

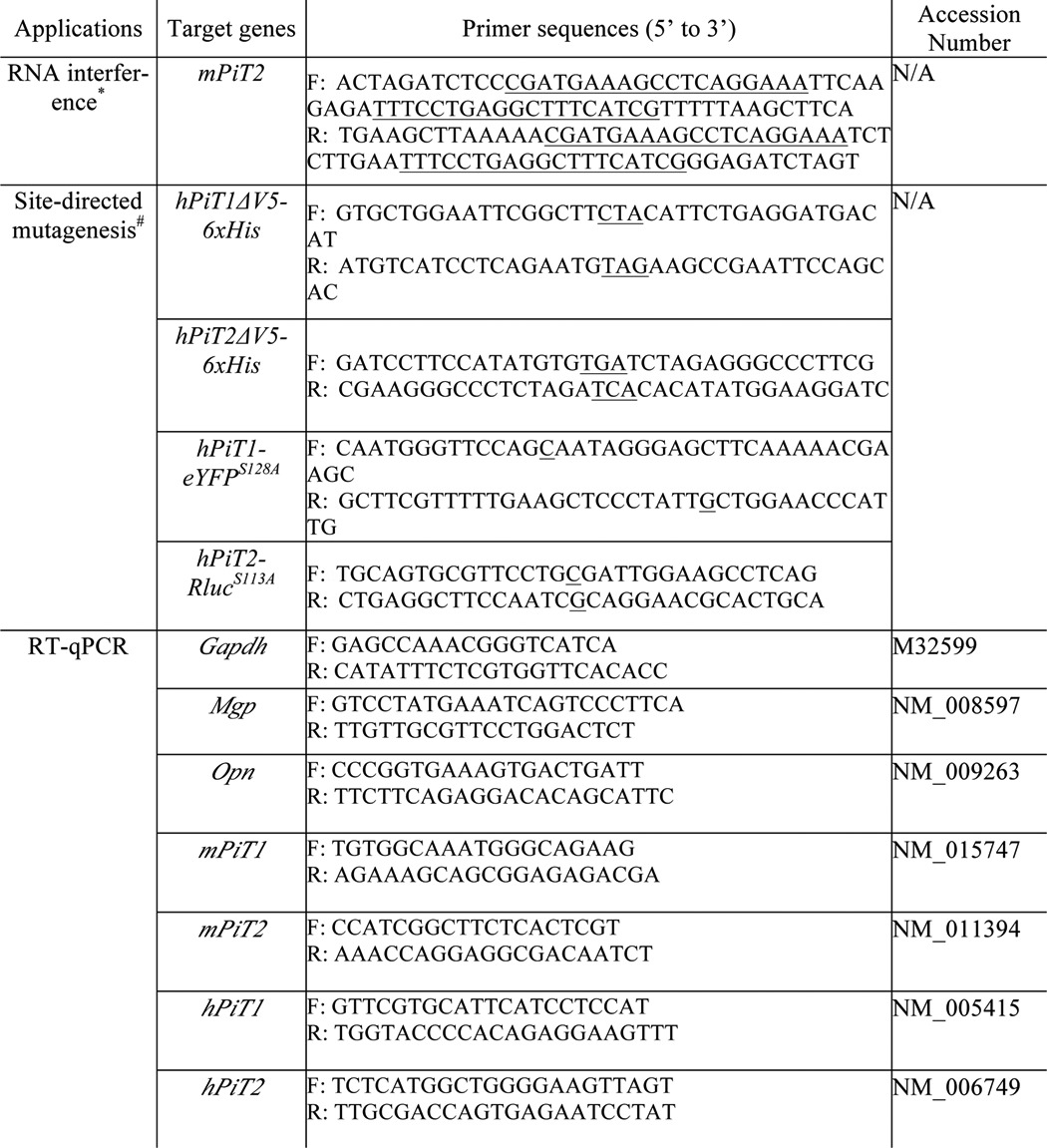

RNA interference

Inactivation of PiT1 or PiT2 were performed by cloning an shPiT1 (56) or shPiT2 (see sequences in Table 1) into pSUPER vector (68) expressing a puromycin resistance gene. A scramble sequence cloned into pSUPER was used as a negative control (56). Stable knockdown of PiT1 or PiT2 was obtained by transfecting MC3T3-E1 cells with 5 μg of the pSUPER-shRNAs using the T-20 program of the Amaxa nucleofector system (Cell Line NucleofectorTM Kit V VCA-1003, Lonza, Bâle, Switzerland). Cells were plated at limiting density, and puromycin-resistant clones were picked, expanded, and tested for PiT expression. Experiments were performed with three independent stable transfectants, and the data presented illustrate a representative clone. Transient inactivation of PiT was also performed in MC3T3-E1 and MC615 cells using transfection as described above. These transient experiments were stopped 72 h after transfection.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for RNA interference, site-directed mutagenesis and RT-qPCR

m, mouse; h, human; F, Forward primer; R, Reverse primer. N/A, not applicable.

*, siRNA sequences are underlined.

#, desired mutation is underlined.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed using Affinity Script (Agilent Genomics, Santa Clara, CA) as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Real-time PCR was performed on a Mx3000P system (Stratagene, San Diego, CA) using Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR QPCR Master Mix (Agilent Genomics). The following temperature profile was used: denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, amplification during 40 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 20 s at 60 °C, followed by a step at 95 °C for 1 min and 65 °C for 30 s. Expression of target genes were normalized to GAPDH expression levels and were calculated as described previously (69). Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

One day after transient transfection, MC615 cells were fixed/permeabilized in methanol at −20 °C for 5 min and blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Immunodetection of PiT1 and PiT2 was performed using rabbit anti-mouse PiT1 or PiT2 antibody, respectively (generously provided by Dr. G. Friedlander), at a 1:200 dilution overnight at 4 °C, and goat anti-rabbit Alexa488 secondary antibody (catalogue no. A11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:1,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. The nuclei were counterstained using 1 μg/ml TO-PRO 3 iodide solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The stained cells were mounted in Prolong Antifade mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000E confocal microscope (Nikon, Badhoevedorp, The Netherlands) equipped with a ×60 oil immersion objective. The averaged intensity for PiT1 and PiT2 staining was determined using Metamorph version 7.5 software.

HEK293T cells were seeded at 3 × 104 cells/cm2 in μ-slide 8-well ibiTreat (catalogue no. 80826, Ibidi, Madison, WI) precoated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were transfected with 0.125 μg/well of plasmid using JetPrime (Polyplus transfection, Illkirch, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, HEK293T cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. Immunodetection of hPiT1-Rluc, hPiT2-Rluc, and BTN3A2-Rluc was performed using anti-Rluc antibody (catalogue no. GTX47953, GeneTex, Irvine, CA) at a 1:200 dilution overnight at 4 °C and goat anti-rabbit Alexa488 secondary antibody (catalogue no. A11008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 1:1,000 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. Nucleus staining was performed using 2 μg/ml Hoescht solution (catalogue no. H3569, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and immunofluorescence was preserved in Citifluor AF1 (Biovalley, Nanterre, France). Images were acquired with a Nikon A1Rsi confocal microscope (Nikon, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a ×60 oil immersion objective.

Phosphate uptake measurements

HEK293T cells were seeded at 105 cells/cm2 in poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich)–precoated 24-well plates. Cells were transfected with 0.5 μg/well of plasmid using JetPrime (Polyplus transfection) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pi uptake in HEK293T cells was measured 24 h after transfection. To perform uptake experiments in MC3T3-E1 cells, PiT-depleted MC3T3-E1 clones were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2, and uptake was performed 24 h later. Pi uptake was performed as described previously (70). Briefly, after three washing steps, cells were incubated in an uptake medium containing 100 μm [32P]KH2PO4 (0.5 μCi/ml) in the presence of 137 mm NaCl (total Pi transport) or N-methyl-d-glucamine (sodium-independent transport) at 37 °C for 10 min. sodium-dependent Pi transport was calculated as the difference between total and sodium-independent Pi transports. Cells were washed three times and lysed with 0.1 m NaOH solution, and aliquots of cell lysates were taken for the determination of protein content (Pierce BCA protein assay kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the radioactivity by liquid scintillation counting (Ultima Gold LLT, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in a Hidex 300 SL β counter.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed for 30 min in ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mm potassium chloride, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 20 mm β-glycerophosphate, 2 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 mm NaF). After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the protein extracts (supernatants) were boiled in Laemmli loading buffer before SDS-PAGE. For cross-linking experiments, proteins were not boiled, and electrophoresis was done on NuPAGETM 3–8% Tris acetate gel (catalogue no. EA0378BOX, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane, and blocking was performed with 5% nonfat dry milk/TBST (10 mm Tris, 154 mm NaCl, 0.15% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were probed with primary antibodies in 5% nonfat dry milk/TBST overnight at 4 °C followed by secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Anti-ERK1/2 (catalogue no. 9102) and anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (catalogue no. 4370) were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) and used at a 1:2,000 dilution. Anti-PiT1 (catalogue no. 12423-1-AP) and anti-PiT2 (catalogue no. 12820-1-AP) were from ProteinTech (Rosemont, IL) and used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Anti-Na/K-ATPase (catalogue no. ab7671) was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK) and used at a 1:5,000 dilution. Monoclonal anti-β-actin clone AC-74 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a 1:5,000 dilution as a loading control. Anti-rabbit (catalogue no. 7074, Cell Signaling) and anti-mouse (catalogue no. A9917, Sigma-Aldrich) secondary antibodies were used at 1:2,000 and 1:80,000 dilutions, respectively. Signal detection was performed using ECL Western blotting detection reagent and ECL hyperfilm (GE Healthcare) or ChemiDoc Imaging SystemTM (Bio-Rad).

Crude cellular fractionation and cross-linking

HEK293T cells were seeded at 105 cells/cm2 in 6-well plates and transfected with 1 μg/well each of hPiT1 and hPiT2 plasmids using JetPrime (Polyplus transfection) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were scraped and lysed in 1 ml of buffer A/well (10 mm Hepes, pH 7, 10% sucrose, 5 mm EDTA, Phosphatase Inhibitor Mixture 3 (catalogue no. P0044), and Protease Inhibitor Mixture (catalogue no. P8340) from Sigma-Aldrich. Lysates were passed 10 times through a 22-gauge 1-ml syringe and centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Pellet (fraction 1; F1) was resuspended in 20 μl of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 20 mm EDTA, Phosphatase Inhibitor Mixture 3, and Protease Inhibitor Mixture). The supernatant was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant (Fraction 2; F2) was reserved. The pellet (Fraction 3; F3) was resuspended in 20 μl of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer and submitted to two freeze/thaw cycles, a 10-min incubation at 100 °C, and a 30-s sonication. All fractions were incubated 1 h at 4 °C with gentle mix. F3 was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and supernatant was used for analysis.

For cross-linking experiments, transfected HEK293T cells were washed three times in cold PBS and cross-linked 30 min at 4 °C with 1 mm bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (catalogue no. 21580, Thermo Fisher Scientific). This cell surface cross-linker was blunted with ice-cold 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, for 15 min and washed twice with cold PBS. Cells were then lysed in Buffer A and processed for cell fractionation as described above.

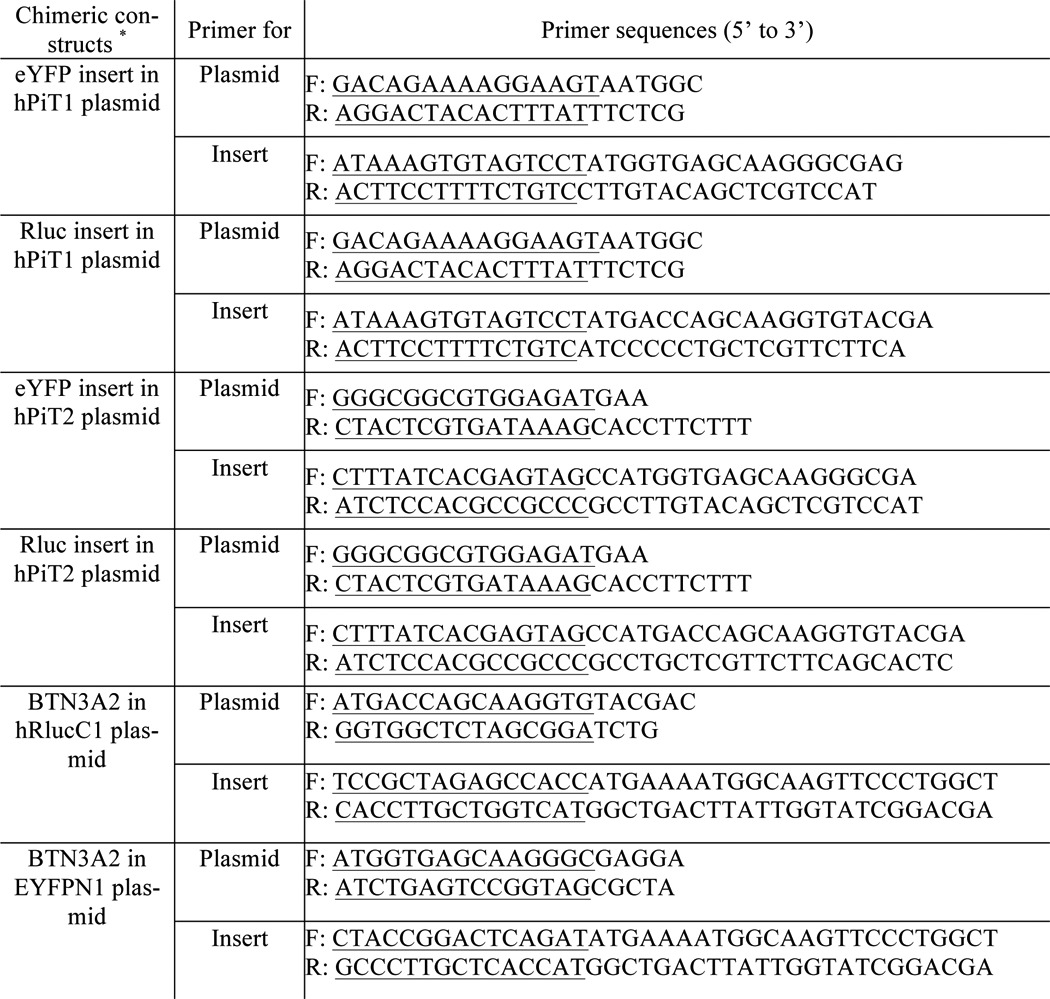

Construction of chimeric and transport-deficient PiT plasmids

The hPiT1 and hPiT2 sequences were previously cloned into pcDNA6A plasmid (56). The V5-His6 fusion tag sequence present in pcDNA6A was excluded by introducing a stop codon at the end of the hPiT coding sequence using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange, Agilent Genomics) (see primers in Table 1). The iLoop of hPiT1 and hPiT2 was then replaced by eYFP or RLuc proteins using FastCloning (71). Briefly, using Phusion® high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) and overlapping specific primers (Table 2), we PCR-amplified the pcDNA6A-hPiT1 and pcDNA6A-hPiT2 vectors with the exception of the iLoop regions and the coding regions of eYFP and Rluc from pEYFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and phRluc-C1 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) plasmids, respectively. After digestion of the DNA templates by DpnI, PCR-amplified overlapping sequences were reassembled by E. coli-mediated recombination-ligation following transformation in high-efficiency NEB® 10-β competent cells (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). In the final hPiT1-eYFP or -Rluc chimeric constructs, the eYFP or Rluc coding sequences were inserted in place of iLoop1 (amino acids 268–492). Similarly, the eYFP or Rluc coding sequence was inserted in place of iLoop2 (amino acids 256–450) in the hPiT2-eYFP or -Rluc constructs. The integrity of the constructs was verified by sequencing. To serve as a control for BRET experiments, the BTN3A2 DNA sequence (generously provided by Dr. Scotet, INSERM UMR1232, Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie et Immunologie, Nantes-Angers, France), encoding a small cell surface–expressed protein, was fused to the N terminus of eYFP or Rluc coding sequences using the same strategy (primers used are reported in Table 2).

Table 2.

Primer sequences used for FastCloning

*, overlapping sequences underlined.

To generate transport-deficient mutant versions of hPiT1-eYFP and hPiT2-Rluc chimeric constructs, we replaced the Ser128 of hPiT1 or Ser113 of hPiT2 by an alanine using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange, Agilent Genomics), as reported previously (56, 63). The sequences of the primers used are listed in Table 1.

BRET saturation assays

HEK293T cells were seeded at 5 × 104 cells/cm2 in 12-well plates. The next day, cells were co-transfected using JetPrime (Polyplus transfection) with a fixed amount of hPiT1-Rluc (50 ng/well), hPiT2-Rluc (100 ng/well), or BTN3A2-Rluc (10 ng/well) plasmids (encoding BRET donors) and variable amounts of hPiT1-eYFP or hPiT2-eYFP (from 12.5 to 1,500 ng/well) or BTN3A2-eYFP (from 1.56 to 50 ng/well) plasmids (encoding BRET acceptors). The pcDNA6A empty vector was used to compensate for the variable amounts of transfected DNA and to ensure equivalent transfection conditions in each well. Twenty-four hours later, transfected cells were detached using 0.5 mm EDTA solution and seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2 in white flat bottom 96-well plates in duplicate. BRET experiments were performed 48 h post-transfection. Cells were washed once with 0.9% NaCl solution and stimulated with various concentrations of Pi for 10 min. Pi was added as a mixture of NaH2PO4 and Na2HPO4 (pH 7.4). When indicated, cells were previously starved of Pi by incubating cells overnight with DMEM high glucose no phosphates (catalogue no. 11971, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mm HEPES, and 50 μg/ml gentamicin before Pi stimulation. The coelenterazine h substrate (UPR3078, Interchim Uptima, Montluçon, France) was added at a final concentration of 5 μm by automated injection in the Mithras LB940 plate reader (Berthold Technologies, Versailles, France), and 485- and 530-nm light emissions were measured consecutively several times. The BRET ratio was calculated as the ratio of light emitted by the acceptor fusion protein at 530 nm over the light emitted by the donor fusion protein at 485 nm. Values were corrected with the background signal calculated from a well without donor fusion protein. The BRET 50 was calculated as the eYFP/Rluc value at which the BRET ratio is half of the maximum BRET ratio achieved at saturating substrate concentration.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. GraphPad version 5.0 software was used to perform Mann–Whitney tests. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise stated, experiments were repeated at least three times.

Author contributions

N.B., G.C., and A.B. conducted most of the experiments, from conception and design to acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data. S.S. provided technical assistance. L.B., J.G., and S.B.C. conceived the idea and supported the coordination of the project. N.B. and L.B. wrote the paper. N.B., G.C., A.B., S.B.C., J.G., and L.B. made adjustments to the final paper version. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the IMPACT platform of the Federative Research Structure François Bonamy (Nantes, France) for technical support and expertise to carry out the BRET assays. Specifically, we gratefully acknowledge Dr. Fabien Gautier for help with this technique. We also thank Philippe Hulin and Steven Nedellec of the Cellular and Tissular Imaging Core Facility (MicroPICell) of the Federative Research Structure François Bonamy (Nantes, France) for assistance with confocal microscopy.

This work was supported by in part grants from INSERM, Région des Pays de la Loire (CIMATH 2, Nouvelle Equipe/Nouvelle Thématique and SENSEO). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Figs. S1–S5.

- Pi

- inorganic phosphate

- iLoop

- large intracellular loop

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- eYFP

- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- BRET

- bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- F1–F3

- fractions 1–3, respectively.

References

- 1. Berner Y. N., and Shike M. (1988) Consequences of phosphate imbalance. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 8, 121–148 10.1146/annurev.nu.08.070188.001005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walser M. (1961) Ion association. VI. Interactions between calcium, magnesium, inorganic phosphate, citrate and protein in normal human plasma. J. Clin. Invest. 40, 723–730 10.1172/JCI104306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marshall W. (1976) Plasma fractions. In Calcium, Phosphate, and Magnesium Metabolism (Nordin B. E. C., ed) pp. 162–185, Churchill Livingstone, London [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knochel J. P. (1977) The pathophysiology and clinical characteristics of severe hypophosphatemia. Arch. Intern. Med. 137, 203–220 10.1001/archinte.1977.03630140051013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klahr S., and Peck W. A. (1980) Cyclic nucleotides in bone and mineral metabolism. II. Cyclic nucleotides and the renal regulation of mineral metabolism. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 13, 133–180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camalier C. E., Yi M., Yu L. R., Hood B. L., Conrads K. A., Lee Y. J., Lin Y., Garneys L. M., Bouloux G. F., Young M. R., Veenstra T. D., Stephens R. M., Colburn N. H., Conrads T. P., and Beck G. R. (2013) An integrated understanding of the physiological response to elevated extracellular phosphate. J. Cell Physiol. 228, 1536–1550 10.1002/jcp.24312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck G. R. Jr., Zerler B., and Moran E. (2000) Phosphate is a specific signal for induction of osteopontin gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8352–8357 10.1073/pnas.140021997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khoshniat S., Bourgine A., Julien M., Weiss P., Guicheux J., and Beck L. (2011) The emergence of phosphate as a specific signaling molecule in bone and other cell types in mammals. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 205–218 10.1007/s00018-010-0527-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michigami T. (2013) Extracellular phosphate as a signaling molecule. Contrib. Nephrol. 180, 14–24 10.1159/000346776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magne D., Bluteau G., Faucheux C., Palmer G., Vignes-Colombeix C., Pilet P., Rouillon T., Caverzasio J., Weiss P., Daculsi G., and Guicheux J. (2003) Phosphate is a specific signal for ATDC5 chondrocyte maturation and apoptosis-associated mineralization: possible implication of apoptosis in the regulation of endochondral ossification. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 1430–1442 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mansfield K., Rajpurohit R., and Shapiro I. M. (1999) Extracellular phosphate ions cause apoptosis of terminally differentiated epiphyseal chondrocytes. J. Cell Physiol. 179, 276–286 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199906)179:3%3C276::AID-JCP5%3E3.0.CO%3B2-# [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teixeira C. C., Mansfield K., Hertkorn C., Ischiropoulos H., and Shapiro I. M. (2001) Phosphate-induced chondrocyte apoptosis is linked to nitric oxide generation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 281, C833–C839 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.3.C833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mansfield K., Teixeira C. C., Adams C. S., and Shapiro I. M. (2001) Phosphate ions mediate chondrocyte apoptosis through a plasma membrane transporter mechanism. Bone 28, 1–8 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00409-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sabbagh Y., Carpenter T. O., and Demay M. B. (2005) Hypophosphatemia leads to rickets by impairing caspase-mediated apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9637–9642 10.1073/pnas.0502249102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khoshniat S., Bourgine A., Julien M., Petit M., Pilet P., Rouillon T., Masson M., Gatius M., Weiss P., Guicheux J., and Beck L. (2011)Phosphate-dependent stimulation of MGP and OPN expression in osteoblasts via the ERK1/2 pathway is modulated by calcium. Bone 48, 894–902 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Julien M., Khoshniat S., Lacreusette A., Gatius M., Bozec A., Wagner E. F., Wittrant Y., Masson M., Weiss P., Beck L., Magne D., and Guicheux J. (2009) Phosphate-dependent regulation of MGP in osteoblasts: role of ERK1/2 and Fra-1. J. Bone Miner. Res. 24, 1856–1868 10.1359/jbmr.090508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miedlich S. U., Zalutskaya A., Zhu E. D., and Demay M. B. (2010) Phosphate-induced apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes is associated with a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and is dependent upon Erk1/2 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18270–18275 10.1074/jbc.M109.098616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Julien M., Magne D., Masson M., Rolli-Derkinderen M., Chassande O., Cario-Toumaniantz C., Cherel Y., Weiss P., and Guicheux J. (2007) Phosphate stimulates matrix Gla protein expression in chondrocytes through the extracellular signal regulated kinase signaling pathway. Endocrinology 148, 530–537 10.1210/en.2006-0763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beck G. R. Jr., and Knecht N. (2003) Osteopontin regulation by inorganic phosphate is ERK1/2-, protein kinase C-, and proteasome-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41921–41929 10.1074/jbc.M304470200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adams C. S., Mansfield K., Perlot R. L., and Shapiro I. M. (2001) Matrix regulation of skeletal cell apoptosis: role of calcium and phosphate ions. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20316–20322 10.1074/jbc.M006492200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beck G. R. Jr., Moran E., and Knecht N. (2003) Inorganic phosphate regulates multiple genes during osteoblast differentiation, including Nrf2. Exp. Cell Res. 288, 288–300 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00213-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conrads K. A., Yi M., Simpson K. A., Lucas D. A., Camalier C. E., Yu L. R., Veenstra T. D., Stephens R. M., Conrads T. P., and Beck G. R. (2005) A combined proteome and microarray investigation of inorganic phosphate-induced pre-osteoblast cells. Mol. Cell Proteomics 4, 1284–1296 10.1074/mcp.M500082-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naviglio S., Spina A., Chiosi E., Fusco A., Illiano F., Pagano M., Romano M., Senatore G., Sorrentino A., Sorvillo L., and Illiano G. (2006) Inorganic phosphate inhibits growth of human osteosarcoma U2OS cells via adenylate cyclase/cAMP pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 98, 1584–1596 10.1002/jcb.20892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshiko Y., Candeliere G. A., Maeda N., and Aubin J. E. (2007) Osteoblast autonomous Pi regulation via Pit1 plays a role in bone mineralization. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4465–4474 10.1128/MCB.00104-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foster B. L., Nociti F. H. Jr., Swanson E. C., Matsa-Dunn D., Berry J. E., Cupp C. J., Zhang P., and Somerman M. J. (2006) Regulation of cementoblast gene expression by inorganic phosphate in vitro. Calcif. Tissue Int. 78, 103–112 10.1007/s00223-005-0184-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lundquist P. (2002) Odontoblast phosphate and calcium transport in dentinogenesis. Swed. Dent. J. Suppl., 1–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bourgine A., Beck L., Khoshniat S., Wauquier F., Oliver L., Hue E., Alliot-Licht B., Weiss P., Guicheux J., and Wittrant Y. (2011) Inorganic phosphate stimulates apoptosis in murine MO6-G3 odontoblast-like cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 56, 977–983 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanatani M., Sugimoto T., Kano J., Kanzawa M., and Chihara K. (2003) Effect of high phosphate concentration on osteoclast differentiation as well as bone-resorbing activity. J. Cell Physiol. 196, 180–189 10.1002/jcp.10270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Takeyama S., Yoshimura Y., Deyama Y., Sugawara Y., Fukuda H., and Matsumoto A. (2001) Phosphate decreases osteoclastogenesis in coculture of osteoblast and bone marrow. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 282, 798–802 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mozar A., Haren N., Chasseraud M., Louvet L., Mazière C., Wattel A., Mentaverri R., Morlière P., Kamel S., Brazier M., Mazière J. C., and Massy Z. A. (2008) High extracellular inorganic phosphate concentration inhibits RANK-RANKL signaling in osteoclast-like cells. J. Cell Physiol. 215, 47–54 10.1002/jcp.21283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hyde R., Cwiklinski E. L., MacAulay K., Taylor P. M., and Hundal H. S. (2007) Distinct sensor pathways in the hierarchical control of SNAT2, a putative amino acid transceptor, by amino acid availability. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19788–19798 10.1074/jbc.M611520200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown E. M., Gamba G., Riccardi D., Lombardi M., Butters R., Kifor O., Sun A., Hediger M. A., Lytton J., and Hebert S. C. (1993) Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature 366, 575–580 10.1038/366575a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacDonald P. E., Joseph J. W., and Rorsman P. (2005) Glucose-sensing mechanisms in pancreatic beta-cells. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 360, 2211–2225 10.1098/rstb.2005.1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bergwitz C., and Jüppner H. (2011) Phosphate sensing. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 18, 132–144 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kumar R. (2009) Phosphate sensing. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 18, 281–284 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32832b5094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Silver J., and Dranitzki-Elhalel M. (2003) Sensing phosphate across the kingdoms. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 12, 357–361 10.1097/00041552-200307000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qi W., Baldwin S. A., Muench S. P., and Baker A. (2016) Pi sensing and signalling: from prokaryotic to eukaryotic cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 44, 766–773 10.1042/BST20160026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lamarche M. G., Wanner B. L., Crépin S., and Harel J. (2008) The phosphate regulon and bacterial virulence: a regulatory network connecting phosphate homeostasis and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 461–473 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mouillon J. M., and Persson B. L. (2006) New aspects on phosphate sensing and signalling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 6, 171–176 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Popova Y., Thayumanavan P., Lonati E., Agrochão M., and Thevelein J. M. (2010) Transport and signaling through the phosphate-binding site of the yeast Pho84 phosphate transceptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2890–2895 10.1073/pnas.0906546107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Olah Z., Lehel C., Anderson W. B., Eiden M. V., and Wilson C. A. (1994) The cellular receptor for gibon ape leukemia virus is a novel high affinity sodium-dependent phosphate transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 25426–25431 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miller D. G., and Miller A. D. (1994) A family of retroviruses that utilize related phosphate transporters for cell entry. J. Virol. 68, 8270–8276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kavanaugh M. P., Miller D. G., Zhang W., Law W., Kozak S. L., Kabat D., and Miller A. D. (1994) Cell-surface receptors for gibbon ape leukemia virus and amphotropic murine retrovirus are inducible sodium-dependent phosphate symporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 7071–7075 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zoidis E., Ghirlanda-Keller C., Gosteli-Peter M., Zapf J., and Schmid C. (2004) Regulation of phosphate (Pi) transport and NaPi-III transporter (Pit-1) mRNA in rat osteoblasts. J. Endocrinol. 181, 531–540 10.1677/joe.0.1810531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Collins J. F., Bai L., and Ghishan F. K. (2004) The SLC20 family of proteins: dual functions as sodium-phosphate cotransporters and viral receptors. Pflugers Arch. 447, 647–652 10.1007/s00424-003-1088-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chien M. L., Foster J. L., Douglas J. L., and Garcia J. V. (1997) The amphotropic murine leukemia virus receptor gene encodes a 71-kilodalton protein that is induced by phosphate depletion. J. Virol. 71, 4564–4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chien M. L., O'Neill E., and Garcia J. V. (1998) Phosphate depletion enhances the stability of the amphotropic murine leukemia virus receptor mRNA. Virology 240, 109–117 10.1006/viro.1997.8933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kimata M., Michigami T., Tachikawa K., Okada T., Koshimizu T., Yamazaki M., Kogo M., and Ozono K. (2010) Signaling of extracellular inorganic phosphate up-regulates cyclin D1 expression in proliferating chondrocytes via the Na+/Pi cotransporter Pit-1 and Raf/MEK/ERK pathway. Bone 47, 938–947 10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miyamoto K., Tatsumi S., Segawa H., Morita K., Nii T., Fujioka A., Kitano M., Inoue Y., and Takeda E. (1999) Regulation of PiT-1, a sodium-dependent phosphate co-transporter in rat parathyroid glands. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 14, 73–75 10.1093/ndt/14.suppl_1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Salaün C., Gyan E., Rodrigues P., and Heard J. M. (2002) Pit2 assemblies at the cell surface are modulated by extracellular inorganic phosphate concentration. J. Virol. 76, 4304–4311 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4304-4311.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ravera S., Virkki L. V., Murer H., and Forster I. C. (2007) Deciphering PiT transport kinetics and substrate specificity using electrophysiology and flux measurements. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C606–C620 10.1152/ajpcell.00064.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Forand A., Koumakis E., Rousseau A., Sassier Y., Journe C., Merlin J.-F., Leroy C., Boitez V., Codogno P., Friedlander G., and Cohen I. (2016) Disruption of the Phosphate transporter Pit1 in hepatocytes improves glucose metabolism and insulin signaling by modulating the USP7/IRS1 interaction. Cell Rep. 16, 2736–2748 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Forand A., Beck L., Leroy C., Rousseau A., Boitez V., Cohen I., Courtois G., Hermine O., and Friedlander G. (2013) EKLF-driven PIT1 expression is critical for mouse erythroid maturation in vivo and in vitro. Blood 121, 666–678 10.1182/blood-2012-05-427302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salaün C., Leroy C., Rousseau A., Boitez V., Beck L., and Friedlander G. (2010) Identification of a novel transport-independent function of PiT1/SLC20A1 in the regulation of TNF-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34408–34418 10.1074/jbc.M110.130989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chavkin N. W., Chia J. J., Crouthamel M. H., and Giachelli C. M. (2015) Phosphate uptake-independent signaling functions of the type III sodium-dependent phosphate transporter, PiT-1, in vascular smooth muscle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 333, 39–48 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Beck L., Leroy C., Salaün C., Margall-Ducos G., Desdouets C., and Friedlander G. (2009) Identification of a novel function of PiT1 critical for cell proliferation and independent of its phosphate transport activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31363–31374 10.1074/jbc.M109.053132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Salaün C., Rodrigues P., and Heard J. M. (2001) Transmembrane topology of PiT-2, a phosphate transporter-retrovirus receptor. J. Virol. 75, 5584–5592 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5584-5592.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yamazaki M., Ozono K., Okada T., Tachikawa K., Kondou H., Ohata Y., and Michigami T. (2010) Both FGF23 and extracellular phosphate activate Raf/MEK/ERK pathway via FGF receptors in HEK293 cells. J. Cell Biochem. 111, 1210–1221 10.1002/jcb.22842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Farrell K. B., Tusnady G. E., and Eiden M. V. (2009) New structural arrangement of the extracellular regions of the phosphate transporter SLC20A1, the receptor for gibbon ape leukemia virus. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29979–29987 10.1074/jbc.M109.022566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bøttger P., and Pedersen L. (2011) Mapping of the minimal inorganic phosphate transporting unit of human PiT2 suggests a structure universal to PiT-related proteins from all kingdoms of life. BMC Biochem. 12, 21 10.1186/1471-2091-12-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bøttger P., and Pedersen L. (2004) The central half of Pit2 is not required for its function as a retroviral receptor. J. Virol. 78, 9564–9567 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9564-9567.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bøttger P., and Pedersen L. (2005) Evolutionary and experimental analyses of inorganic phosphate transporter PiT family reveals two related signature sequences harboring highly conserved aspartic acids critical for sodium-dependent phosphate transport function of human PiT2. FEBS J. 272, 3060–3074 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Salaün C., Maréchal V., and Heard J. M. (2004) Transport-deficient Pit2 phosphate transporters still modify cell surface oligomers structure in response to inorganic phosphate. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 39–47 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bottger P., and Pedersen L. (2002) Two highly conserved glutamate residues critical for type III sodium-dependent phosphate transport revealed by uncoupling transport function from retroviral receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42741–42747 10.1074/jbc.M207096200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shapiro I. M., and Boyde A. (1984) Microdissection-elemental analysis of the mineralizing growth cartilage of the normal and rachitic chick. Metab. Bone Dis. Relat. Res. 5, 317–326 10.1016/0221-8747(84)90019-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thevelein J. M., and Voordeckers K. (2009) Functioning and evolutionary significance of nutrient transceptors. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 2407–2414 10.1093/molbev/msp168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kriel J., Haesendonckx S., Rubio-Texeira M., Van Zeebroeck G., and Thevelein J. M. (2011) From transporter to transceptor: signaling from transporters provokes re-evaluation of complex trafficking and regulatory controls. BioEssays 33, 870–879 10.1002/bies.201100100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brummelkamp T. R., Bernards R., and Agami R. (2002) A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 296, 550–553 10.1126/science.1068999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Livak K. J., and Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Escoubet B., Silve C., Balsan S., and Amiel C. (1992) Phosphate transport by fibroblasts from patients with hypophosphataemic vitamin D-resistant rickets. J. Endocrinol. 133, 301–309 10.1677/joe.0.1330301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Li C., Wen A., Shen B., Lu J., Huang Y., and Chang Y. (2011) FastCloning: a highly simplified, purification-free, sequence- and ligation-independent PCR cloning method. BMC Biotechnol. 11, 92–102 10.1186/1472-6750-11-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.