Abstract

Using longitudinal, experience sampling data from 214 ethnic/racial minority adolescents (Wave 1 Mean age = 15.24), the present study investigated how the longitudinal effect of parental cultural socialization on adolescent private regard was mediated through various daily pathways and novel constructs. Both the mean levels and variability of adolescents’ ethnic feelings (i.e. private regard) and social interactions (i.e. intragroup contact) in daily situations, as well as the situational association between intragroup contact and private regard, emerged as mediators. Greater cultural socialization promoted greater and more stable ethnic feelings and interactions, as well as their situational association, all of which promoted private regard over time. This study provides a framework to explore how development occurs in daily lives.

Keywords: cultural socialization, private regard, daily mediation, variability, associative mediation

Ethnic/racial identity helps adolescents navigate a culturally, ethnically/racially diverse society, and for this reason, the social context in which ethnic/racial identity (ERI) is constructed has received extensive research attention (Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). The role of family context, particularly parents’ efforts to teach young people about their ethnic culture (i.e., cultural socialization; Hughes et al., 2006), in shaping adolescents’ ERI has been a key focus of this discovery process. While existing studies have documented the direct link between parental cultural socialization and adolescents’ positive feelings towards their ethnic/racial groups using cross-sectional or longitudinal data (Hernández, Conger, Robins, Bacher, & Widaman, 2014; Rodriguez, Umaña-Taylor, Smith, & Johnson, 2009), how parental cultural socialization is enacted in adolescents’ daily lives is less clear. As young people move through adolescence, their social environments become increasingly complex (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Adolescents’ feelings towards their ethnic/racial groups (Kiang, Yip, Gonzales-Backen, Witkow, & Fulgni, 2006; Yip & Fulgni, 2002) and social interactions (e.g., intragroup and intergroup contact; Shelton, Douglass, Garcia, Yip, & Trail, 2014; Yip, Douglass, & Shelton, 2013) also vary substantially from situation to situation and day to day. Given these variations and complexities, whether and how parental cultural socialization translates into long-term development through adolescents’ daily experiences is an open question. Drawing upon theories that highlight the importance of daily experiences for development (Lam & McHale, 2015; Weisner, 2002), the present study investigates how adolescents’ situational experiences may mediate the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and adolescents’ ERI.

Although existing work has investigated the social influences of ERI on a daily basis (Kiang et al., 2006; Yip & Fulgni, 2002) and over time (Rivas-Drake & Witherspoon, 2013; Seaton, Yip, & Sellers, 2009), there is less research integrating these two perspectives to elucidate the exact mechanisms through which contexts influence long-term development through individuals’ daily or situational experiences. The present study proposes multiple daily pathways underlying the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and adolescent ERI. We adopt novel methodologies based on experience sampling data to capture various aspects of adolescents’ situational experiences, including the stability (i.e., an adolescent’s average level) and variability (i.e., how much an adolescent varies from his/her own average) in their experiences, as well as dynamic relationships between situational events. We focus on adolescents’ situational ethnic feelings and social interactions which have been implicated in ERI development (i.e., intragroup; Yip et al., 2013) as potential mediators. Informed by the life course theory, which posits that particular social circumstances and dynamic linkages between social experiences accumulate to influence development (Elder, Shanahan, & Jennings, 2015), we hypothesize that parental cultural socialization promotes ERI not only through positive experiences of one’s ethnicity/race across situations (e.g., positive ethnic/racial affect, intragroup contact), but also by setting in motion dynamic linkages between adolescents’ social interactions and ethnic/racial affect. We focus on a particular dimension of ERI development, private regard, or how positively adolescents feel about their ethnic/racial group membership (Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998), as this dimension is closely tied to well-being (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014) and parental cultural socialization goals (Rodriguez et al., 2009).

Parental Cultural Socialization and Ethnic/Racial Private Regard

Parents are key socializing agents for ERI development (Hughes et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). Parents promote cultural knowledge and pride by explicitly teaching children about their ethnic culture, respecting their ethnic culture, and encouraging children to form friendships with same-ethnic others. Parents are also often responsible for involving adolescents in cultural activities, such as celebrating festivals and preparing ethnic food (Hughes et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor, 2004). By conveying positive messages about their ethnic background through these practices, parents foster youths’ positive feelings towards their ethnic background and thus promote ERI development (Rodriguez et al., 2009). Indeed, empirical work has documented both concurrent and longitudinal links between parental cultural socialization and positive ethnic/racial affect among adolescents from diverse ethnic/racial groups (Else-Quest & Morse, 2015; Hernández et al., 2014).

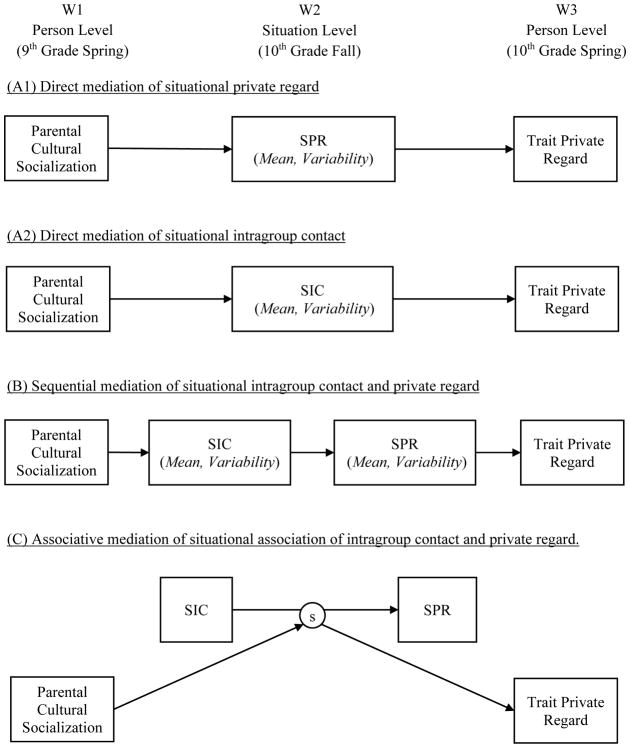

While there is evidence to suggest that parental efforts to socialize their children around ethnicity/race can affect the development of adolescents’ private regard, what is less clear is how these messages are enacted in adolescents’ day-to-day lives. The investigation of daily mediating mechanisms is grounded in theoretical work that stresses the importance of everyday life for development in general (Lam & McHale, 2015; Weisner, 2002; Yip & Douglass, 2013) and identity development in particular (Erikson, 1968; Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). According to these theories, daily activities serve as a medium through which adolescents are exposed to social influences and learning opportunities (Lam & McHale, 2015; Weisner, 2002), and identity evolves through adolescents’ daily experiences and social interactions (Erikson, 1968; Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). The present study builds upon this theoretical base to explore the daily mediating mechanisms that might explain the longitudinal effect of parental cultural socialization on adolescents’ private regard. We focus on adolescents’ feelings (i.e., private regard) and social interactions (i.e., intragroup contact) in their everyday situations as potential mediating mechanisms. We propose and test three types of mediation in four models (Figure 1). The first type, direct mediation, entails two possible models: one model examines situational private regard, quantified as the mean and variability of private regard across situations, as a direct mediator between parent socialization and adolescent private regard in the long term (Panel A1 in Figure 1); another model examines intragroup contact, quantified as the mean and variability of intragroup contact across situations, as the mediator (Panel A2 in Figure 1). In the second type, sequential mediation, parental cultural socialization sets in motion a sequential link from situational intragroup contact to situational private regard, which subsequently predicts the long-term development of private regard (Panel B in Figure 1). Finally, we offer a third type of mediation in our fourth model, associative mediation whereby the association between intragroup contact and private regard serves as the mediator (Panel C in Figure 1). Each of these mediating mechanisms is informed by theoretical and empirical work, which we review below.

Figure 1.

Conceptual models testing the daily mediating pathways for the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and trait private regard. SIC = Situational intragroup contact. SPR = Situational private regard. The latent construct of “s” represents the random slope of intragroup contact predicting private regard.

Direct Mediation of Situational Private Regard: Mean and Variability

Similar to the notions of “trait” and “state” psychological constructs, ERI has been conceptualized in terms of stability and variability (Sellers et al., 1998; Yip & Fulgni, 2002; Yip, 2005). “Trait” ERI is a person-level construct that remains stable across days and situations, yet develops across time through the life-course. In contrast, “state” ERI is fluid and responds to immediate setting and contextual cues. Empirical work has identified considerable variability in adolescents’ daily reports of ERI in general, and private regard in particular (Yip, Douglass & Shelton, 2013; Kiang et al., 2006; Yip & Fulgni, 2002; ). As such, the current study decomposes adolescents’ situational private regard into two dimensions, one capturing their average feelings from situation to situation (i.e., mean level across situations) and the other capturing the changing nature of private regard across situations (i.e., variance level across situations). Prior work demonstrates that both the mean and variability of adolescents’ ethnic/racial experiences in everyday life are related to their ERI developmental processes and well-being (Douglass, Wang, & Yip, 2016; Yip, 2014). Yet, their developmental implications differ. While higher mean levels of daily ERI may be associated with a more developed identity status and more positive well-being, variability in daily experiences may be considered a sign of instability and vulnerability. Indeed, prior work on ethnic/racial salience observed that higher variability in salience across situations was associated with lower levels of committing to one’s ERI (Douglass et al., 2016). Similarly, research on emotional dynamics has also linked mood variability to poorer psychological well-being in the long term (Houben, Van Den Noortgate, & Kuppens, 2015). While limited work has examined how private regard develops through daily experiences, we hypothesize that higher mean levels and lower variability in situational private regard, would be related to higher levels of trait-like private regard in the long term. To distinguish private regard assessed at different time scales, we use “situational” private regard to capture adolescents’ ethnic feelings in their daily situations, and “trait” private regard to capture their ethnic feelings over a relatively long period of time.

Moreover, the present study builds upon prior work to examine the extent to which the mean level and variability of daily private regard mediates the link between parental cultural socialization and trait private regard over time. Because parental cultural socialization practices promote positive affect towards one’s ethnic/racial group (Hughes et al., 2006), adolescents with greater parental cultural socialization will likely report more positive private regard in their daily situations. Parental messages may also serve as a stable resource such that adolescents report consistent feelings towards their ethnic/racial groups across daily situations. Thus, we hypothesize that greater parental cultural socialization will be related to higher mean levels and less variability in private regard in adolescents’ daily lives, which will in turn promote higher levels of trait private regard in the long term (Panel A1 in Figure 1).

Direct Mediation of Situational Intragroup Contact: Mean and Variability

In addition to adolescents’ daily feelings towards their ethnicity/race, adolescents’ daily social interactions may also mediate the longitudinal relation between parental cultural socialization and trait-like private regard. Because adolescents’ world views and self-concepts become increasingly influenced by peers and individuals outside of the family (Côté, 2009; Erikson, 1968), the investigation of how daily interactions play a role in the link between family settings and identity development becomes particularly critical. The present study focuses on intragroup contact across everyday situations as an important process that promotes adolescents’ positive feelings towards their ethnic/racial groups (Yip et al., 2013). A nascent body of work suggests that adolescents receive messages about what it means to be a member of their ethnic/racial group from various socialization agents in and outside their families (Hughes, McGill, Ford, & Tubbs, 2011; Wang & Benner, 2016), and this process is particularly salient in their interactions with same-ethnic others (Kiang & Fuligni, 2008). Indeed, empirical work demonstrates that adolescents with greater intragroup contact are more likely to report an achieved ERI (Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001) or changes in their ERI status (Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2010). Daily diary research demonstrated that more intragroup contact was associated with more positive private regard the next day (Yip et al., 2013).

Building on this research, the current study aims to capture the complexity of adolescents’ daily social interactions, and investigates contact with same-ethnic others using an experience sampling design. Similar to their feelings and private regard in everyday life, adolescents’ social interactions vary from situation to situation (Fuligni, Yip, & Tseng, 2002). This is particularly true given that young people are spending increasing amounts of time outside family settings and engaging in more complex social interactions (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Larson, Richards, Moneta, Holmbeck, & Duckett, 1996). Similar to our investigation of situational private regard, we attend to both the mean level and variability in intragroup contact across adolescents’ daily situations to capture the stability and variability in social interactions. Informed by prior work, we hypothesize that higher mean levels of situational intragroup contact will be related to higher levels of trait private regard in the long term. While there has been limited work on how variability in daily social interactions may impact adolescents’ feelings, we propose that more stable (less variable) situational intragroup contact with same-ethnic others may promote adolescents’ positive private regard in the long term.

In addition to exerting a direct impact on the development of trait private regard, adolescents’ situational intragroup contact may mediate the association between parental socialization and trait private regard in the long term (Panel A2 in Figure 1). The investigation of relations between parental cultural socialization and adolescents’ situational intragroup contact is motivated by developmental theories that emphasize the interdependent nature of developmental settings (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006). Theoretical frameworks focusing on family and peer linkages also highlight the mediating mechanisms whereby parents not only influence adolescent adjustment directly, but also indirectly, by influencing adolescents’ choices of friendships and contacts with others (Brown & Bakken, 2011). In our study, parents may promote adolescents’ intragroup contact through cultural socialization practices. Specifically, parents could exert a direct influence on their children’s peer relationships by encouraging adolescents to associate with same-ethnic others. Indeed, empirical work demonstrates that Latino parents showed more support for their children’s friendships when friends were more oriented towards their ethnic culture (Updegraff, Kim, Killoren, & Thayer, 2010). Parents may also exert an indirect influence by creating opportunities and contexts for their children’s peer interactions (McDowell & Parke, 2009; Parke, Burks, Carson, Neville, & Boyum, 1994). For example, parents could choose neighborhoods or schools that increase the likelihood that their children will have exposure to same-ethnic peers. They may also involve adolescents in cultural activities and events, facilitating increased contact with same-ethnic others. Informed by prior work, we hypothesize that adolescents reporting greater parental cultural socialization will also report greater mean-level intragroup contact in their daily lives across situations, which in turn will promote higher levels of trait private regard in the long term (Panel A2 in Figure 1). Similar to our predictions with respect to situational private regard, we also propose that parental cultural socialization may serve as a stable structure that shapes adolescents’ daily interactions. As such, adolescents who report greater parental socialization will also report more stable (less variable) contact with same-ethnic others in their daily lives.

Sequential Mediation of Situational Intragroup Contact and Situational Private Regard

Moving beyond examining situational intragroup contact and private regard as separate mediators, the present study also investigates the dynamic linkages between potential mediators. This investigation is informed by the life course theory, which posits that chains of interrelated events may accumulate to influence development (Elder et al., 2015). Building upon this theory, the present study conceptualizes the dynamic between situational intragroup contact and private regard using two approaches. We first examined situational intragroup contact and private regard as sequential mediators (Taylor, MacKinnon, & Tein, 2007; or serial mediators in Hayes, 2013) whereby parental cultural socialization structures adolescents’ situational intragroup contact, which, in turn, predicts their situational private regard – and, over time, results in higher levels of trait private regard (Panel B in Figure 1). While the daily associations between intragroup contact and private regard are a relatively new area of inquiry, research has suggested that contact with same-ethnic others predicts subsequent feelings about oneself (Tatum, 1997). Daily diary work also demonstrates that contact precedes feelings of private regard but not the other way around (Yip et al., 2013). Attending to both the stability and variability of adolescents’ situational experiences, we test two sequential mediating pathways simultaneously, one through the mean levels of intragroup contact and private regard, and the other through the variability of the two variables.

Associative Mediation of Situational Association between Intragroup Contact and Private Regard

In addition to examining situational intragroup contact and private regard as sequential mediators, the final approach we use to investigate the dynamics between the two constructs is to focus on their association, or the co-occurrence between intragroup contact and private regard in daily situations, as a daily mediating mechanism. This novel approach moves beyond considering particular constructs as mediators, focusing instead on the strength of relationships. We propose that parental cultural socialization may promote the repeated co-occurrence of situational intragroup contact and situational private regard, and hence a strong positive association between the two constructs across situations. Developmentally, this repeated co-occurrence across situations might promote higher levels of private regard over time (Panel C in Figure 1). The notion of accumulative developmental effects is informed by the life course theory, which suggests that interrelated events occur repeatedly over time to maintain and promote the same behavioral outcomes (Elder et al., 2015). Although the concept of repeated co-occurrence has been suggested in the theoretical work, empirical research has yet to investigate this developmental process. The present study uses experience sampling data and multilevel modeling in a structural equation modeling framework (Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010) to estimate the situational association between intragroup contact and private regard. In this framework, the repeated co-occurrence of these two constructs across situations is captured by a person-level latent construct of their situational associations (i.e., random slope; expressed as the oval “s” in Panel C in Figure 1).

Linking a person-level predictor (e.g., parental cultural socialization) to a random slope (e.g., contact-regard association) is not methodologically new. It is equivalent to a cross-level interaction (Preacher, Zhang, & Zyphur, 2015) such that a person-level predictor (e.g., parental cultural socialization) interact with a situation-level predictor (e.g., situational intragroup contact) to influence a situation-level outcome (e.g., situational private regard). The novelty of our associative mediation approach, however, lies in the latter part of the mediating pathway—the developmental implications of the random slope. In our model, the random slope is not only an outcome (as considered in cross-level interaction), but also a predictor that can translate into long-term development. A similar notion of strength-of-relationship has recently been used in research assessing individuals’ affective responses to stress in daily lives (Charles, Piazza, Mogle, Sliwinski, & Almeida, 2013; Mandel, Dunkley, & Moroz, 2015). By linking the person-level association between daily stress and affect (i.e., stress reactivity) to long-term psychological well-being, this line of work highlights the developmental significance of investigating accumulative affective responses in daily lives.

Applying this approach to the current study, we hypothesize that as parents encourage their children to appreciate their ethnic culture and promote interactions with same-ethnic others (Hughes et al., 2006; Updegraff et al., 2010), adolescents will be more likely to report positive feelings towards their ethnic group when interacting same-ethnic others. That is, they are more likely to exhibit a strong co-occurrence between situational intragroup contact and situational private regard. In turn, individuals who experience a strong, repeated co-occurrence between situational intragroup contact and situational private regard in their daily lives are more likely to report high levels of trait private regard in the long term.

The Current Study

The current study draws data from an ethnically/racially diverse sample of adolescents participating in a longitudinal project with an experience sampling design. To explore the daily mediating mechanisms underlying the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and adolescents’ private regard, we use survey data on family cultural socialization collected when adolescents were in the spring of the 9th grade (Wave 1), experience sampling data on situational private regard and intragroup contact in the fall of the 10th grade (Wave 2), and survey data on trait private regard in the spring of the 10th grade (Wave 3).

The present study investigates three types of mediation in four models (Figure 1). The first pathway tests a direct mediation between Wave 1 parental cultural socialization and Wave 3 private regard through the mean level and variability of situational private regard at Wave 2 (Panel A1 in Figure 1). The second pathway tests a direct mediation through the mean level and variability of situational intragroup contact at Wave 2 (Panel A2 in Figure 1). The third model investigates a sequentially mediated pathway through situational intragroup contact and situational private regard, attending both to their mean levels and to variability across situations (Panel B in Figure 1). Finally, the fourth model represents a novel conceptual and analytical departure from the other models in that it considers the situation-level association between intragroup contact and private regard as a potential mediator (Panel C in Figure 1).

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from adolescents participating in a longitudinal, experience sampling study at five public high schools in New York City. The current sample includes 214 ethnic/racial minority students who participated in the study in the spring of the 9th grade, fall of the 10th grade, and spring of the 10th grade (labeled as Waves 1, 2, and 3 in the present study). This analytic sample is 68% female and includes diverse ethnic/racial minority groups (36% Latinos, 50% Asian Americans, 14% African Americans). A majority (81%) of adolescents were born in the United States. A considerable portion of adolescents reported not knowing the highest level of education completed by their parents (43% for mothers, 45% for fathers), and the next most common response was that their parents completed high school (18% for mothers, 19% for fathers).

Procedure

The research team identified five public schools with varying levels of ethnic/racial composition in New York City. The five schools included a predominantly Asian (58% Asian Americans), a predominantly Latinx (64% Latinx), a predominantly White (47% Whites), and two ethnically/racially diverse (28% Asian Americans, 24% Latinx, 13% African Americans, 34% Whites, 1% other; 16% Asian Americans, 28% Latinx, 22% African Americans, 33% Whites, 1% other) schools. Parental consent letters were sent home to all 9th graders in the fall of 2008 and 2009, drawing in two cohorts of participants (cohort 1: N = 248, cohort 2: N =157). Only students with completed consent and assent forms participated in the study. Data collection occurred in six waves, in the fall and spring semesters from 9th to 11th grade. In each fall semester, participants were invited to complete a survey. They were then given a cellular phone to complete experience sampling reports for the next seven days. To avoid disruption of academic time, participants were randomly prompted after school hours to complete brief surveys five times per day for a week for a total of 35 surveys. Experience-sampling studies employing signal-contingent designs such as the one employed in the current study report response rates in the 50–70% range (Christensen, Barrett, Bliss-Moreau, Lebo, & Kaschub, 2003; Otsuki, Tinsley, Chao, & Unger, 2008), slightly lower than electronic-based diary studies in which participants’ responses are not signal-contingent, but are provided at the end of each day (e.g., 99% in Yip et al., 2013). To encourage compliance, participants were sent daily reminders and were compensated on sliding scale. On average, the response rate was 66% (23 out of 35 possible surveys per person, SD = 11), which is comparable to other signal-contingent experience-sampling studies. In each spring semester, participants completed another round of surveys without the experience sampling reports. Participants were compensated $50, $70, and $90 in the fall semesters from the 9th to 11th grade, and $20 in each spring semester.

While the larger project includes six waves of data, the present study includes the three waves that allow the investigation of our hypothesized models while also retaining the largest sample. In order to capture the temporal order of the study variables, we used data on parental cultural socialization in the spring of the 9th grade (Wave 1), adolescents’ daily experiences in the fall of the 10th grade (Wave 2), and trait private regard in the spring of the 10th grade (Wave 3). The larger project includes 405 adolescents (139 Asian Americans, 102 Latinx, 49 African Americans, 94 Whites, 17 other race/ethnicities, 4 with missing ethnicity/race data) who participated in fall 9th grade (Wave 0). Given our focus on ethnic/racial minorities, we excluded 94 White adolescents and 4 with missing ethnic/racial data. We also excluded 17 students who identified as “other” due to difficulties determining same- versus cross-ethnic groups for these adolescents. Of the remaining 290 adolescents, we further excluded 63 adolescents who did not participate in Wave 2 and 13 adolescents who participated in the survey component but not the experience sampling component in Wave 2. The final analytic sample included 214 ethnic/racial minority adolescents who responded in both the survey and experience sampling components at Wave 2. To explore potential differential attrition, we compared demographic characteristics (i.e., cohort, age, gender, ethnicity/race, nativity) of the analytic sample to: 1) those who did not participated in Wave 2 (N = 63), and 2) those wo participated in the survey component but not the experience sampling component in Wave 2 (N = 13). No significant differences were observed.

Measures

Parental Cultural Socialization

Parental cultural socialization at the person level was assessed using five items adapted from the parental ethnic/racial socialization scale (Hughes & Chen, 1997). At Wave 1, adolescents rated their parents’ practices to promote their ethnic/racial cultural background (e.g., “How often have your parents said you should be proud to be the race or ethnicity that you are?”) using a five-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The internal consistencies were satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = .85 for the analytic sample; .84 for Latinx, .84 for Asian Americans, and .82 for African Americans).

Situational Intragroup Contact

Adolescents’ situational intragroup contact was assessed at Wave 2 using an experience sampling design. Participants were prompted to answer a brief survey five times randomly each day after school for one week. In each survey, adolescents responded to the following question: “Look around and think about the people who you are interacting with. How many of the people who you are interacting with are the same race/ethnicity as you?” (Yip et al., 2013). Adolescents rated their intragroup contact using a five-point scale ranging from 0 (none: 0%) to 4 (all: 100%). On average, each adolescent had 15 assessments (SD = 9) over the course of study. We controlled for the number of assessments for each student in the analyses.

Situational Private Regard

Adolescents’ situational private regard was assessed at Wave 2 using an experience sampling design. When participants were prompted, they rated feelings of private regard on two items (“I am happy that I am a member of my racial/ethnic group”, “I feel good about people of my race/ethnicity”; Yip et al., 2013) using a seven-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 6 (extremely). The two items were highly correlated with each other (r = .89) and averaged together. On average, each adolescent had 23 assessments (SD = 11) over the course of study. We controlled for the number of assessments in the analyses.

Trait Private Regard

Adolescents’ trait private regard at the person-level was assessed by an adapted version of the private regard subscale from the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). At both Waves 1 and 3, adolescents rated their positive feelings toward their ethnic/racial groups on seven items (e.g., “I am happy that I am a member of my racial/ethnic group”) using a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The internal consistencies were satisfactory at both waves (Cronbach’s αs = .74 to .78 for the analytic sample; .72 to .79 for Latinx, .79 to .83 for Asian Americans, and .68 to .86 for African Americans). In the present study, we controlled for adolescents’ private regard at Wave 1 when examining adolescents’ private regard at Wave 3.

Analysis Plan

All analyses were conducted in a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Before testing our hypothesized models, we first used multilevel SEM (MSEM; Preacher et al., 2010) to estimate quantities that were needed in these models: a) mean levels and variability of situational private regard; b) mean levels and variability of situational intragroup contact; and c) situational association between intragroup contact and private regard. These estimates were then saved and used in the primary analyses.

To assess each adolescent’s mean level and variability of situational private regard, we fitted a MSEM model that estimated the situation-level latent component and the person-level latent component of private regard. At the situation-level, prompt order (i.e., 1st to 5th beep for each day), day order (i.e., 1st to 7th day in the study), and weekday indicators (0 = weekday, 1 = weekend) were included as covariates. Mean level of situational private regard for each adolescent was estimated by the mean of the person-level latent component. Variability of situational private regard for each adolescent was estimated by the standard deviation of the situation-level latent component residual (Houben et al., 2015). The mean level and variability of adolescents’ situational intragroup contact were estimated in an identical approach as those of situational private regard. To estimate the association between intragroup contact and private regard across situations, we fitted another MSEM model in which private regard was predicted by intragroup contact at both the situation- and person-levels. These estimates were saved and used to fit the hypothesized mediation models in Figure 1.

Our primary analyses tested the daily mediating mechanisms underlying the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 and trait private regard at Wave 3 in four mediation models in Figure 1. In each mediation model, direct paths were estimated by Mplus. The unstandardized mediation effect was assessed by the product of all the unstandardized path coefficients involved in the mediating pathway. The significance of the mediation effect was determined by its 95% confidence interval using the Monte Carlo method in the RMediation package in R (version 1.1.4; Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2016). The standardized mediation effect is calculated by the unstandardized mediation effect multiplied with the SD of parental cultural socialization and divided by the SD of trait private regard (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Although we had theoretical and empirical support for testing the models above, we also considered alternative models for the sequential and associative mediation models. For the sequential mediation model, we considered an alternative model where the order of situational private regard and intragroup contact were reversed (i.e., parental cultural socialization predicts situational private regard, which predicts situational intragroup contact, all of which predict trait private regard). For the associative mediation model, we considered an alternative model in which the reversed association between private regard and intragroup contact (i.e., private regard predicting intragroup contact) across situations served as the mediator.

All analyses controlled for adolescents’ demographic characteristics (i.e., cohort, gender, ethnicity/race, and nativity) and their trait private regard at Wave 1. We also controlled for the number of assessments of situational variables (i.e., intragroup contact, private regard). The missing data rates were low among all study variables (0% to 3%). Missing data was handled by the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure. We also addressed the nested nature of the data (i.e., students nested in schools) using the cluster feature of Mplus.

Results

Descriptive Statistics of Adolescents’ Daily Experiences

Table 1 shows the means, SDs, and zero-order correlations of all study variables. For adolescents’ daily social interactions at Wave 2, the mean level of situational intragroup contact was .69 (SD = .18), indicating that, on average, adolescents reported that 69% of the people they were interacting with in a situation were from their own ethnic/racial group. The average variability of situational intragroup contact was .25 (SD = .13), suggesting considerable variability in the ethnic/racial composition of adolescents’ social interactions across situations. For adolescents’ daily feelings toward their ethnicity/race, the mean level of private regard was 3.87 (SD = 1.18, ranging from 0 to 6) across situations, indicating relatively positive feelings about their ERI. The average variability of their situational private regard was .76 (SD = .38), suggesting considerable variability in adolescents’ ethnic feelings across situations. For the association between intragroup contact and private regard across situations, the average association was .33 (unstandardized coefficient estimates; SD = .46), indicating some degree of co-occurrence between the two variables in adolescents’ daily lives.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental Cultural Socialization (W1) | ||||||||||||

| 2. Situational Intragroup Contact Mean (W2) | .14 | * | ||||||||||

| 3. Situational Intragroup Contact Variability (W2) | −.13 | −.41 | *** | |||||||||

| 4. Situational Private Regard Mean (W2) | .21 | * | .29 | *** | −.10 | |||||||

| 5. Situational Private Regard Variability (W2) | −.11 | −.10 | .20 | −.03 | ||||||||

| 6. Situational Contact-Regard Association (W2) | .12 | *** | .09 | ** | −.03 | .59 | *** | .30 | *** | |||

| 7. Trait Private Regard (W3) | .31 | *** | .26 | *** | −.06 | .50 | *** | −.19 | ** | .26 | *** | |

| Mean | 3.19 | .69 | .25 | 3.87 | .76 | .33 | 5.17 | |||||

| SD | .93 | .18 | .13 | 1.18 | .38 | .46 | .96 | |||||

Notes. Estimates were obtained from Mplus that handled missing data using full information maximum likelihood (FIML).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Daily Mediation between Parental Cultural Socialization and Trait Private Regard

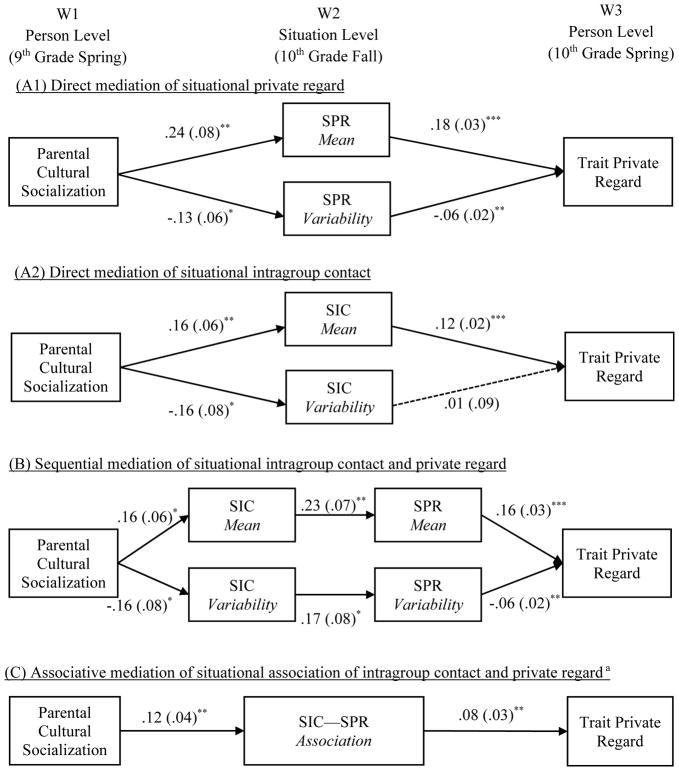

A preliminary path analysis demonstrated that parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was positively linked to adolescents’ private regard at Wave 3 (β = .18, SE = .06, p < .01). As expected, reports of parental cultural socialization were associated with higher levels of trait private regard one year later. We next considered how adolescents’ daily experiences might explain this longitudinal association. Specifically, we explored the four mediation models linking parent socialization at Wave 1 to adolescent private regard at Wave 3. We reported direct path coefficients in Figure 2 and mediation effects in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Standardized coefficient estimates for the daily mediating pathways underlying the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and private regard. Standard errors are shown in parentheses. SIC = Situational intragroup contact. SPR = Situational private regard. Significant paths are depicted by solid lines. Non-significant paths are depicted by dash lines. Although not depicted in the figure, the direct effect of Wave 1 parental cultural socialization on Wave 3 trait private regard was also significant. All analyses controlled for adolescent demographics (i.e., cohort, gender, ethnicity/race, and nativity), trait private regard at Wave 1, and number of assessments of situational variables.

a Model C was also tested within a multilevel structural equation modeling framework which simultaneously estimates the situational intragroup contact and situational private regard and the mediation effect. Similar model relations were observed. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Table 2.

Estimates of Indirect Effects for the Daily Mediating Pathways for the Longitudinal Link between Parental Cultural Socialization and Private Regard

| ab | 95% CI | αβ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A1. Direct mediation of situational private regard | ||||

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SPR Mean (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .041 | [.013, .066] | .040 | * |

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SPR Variability (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .008 | [.000, .023] | .008 | * |

| Model A2. Direct mediation of situational intragroup contact | ||||

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SIC Mean (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .019 | [.004, .035] | .019 | * |

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SIC Variability (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | −.003 | [−.043, .030] | −.003 | |

| Model B. Sequential mediation | ||||

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SIC Mean (W2) → SPR Mean (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .006 | [.000, .014] | .006 | * |

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SIC Variability (W2) → SPR Variability (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .001 | [−.000, .002] a | .001 | † |

| Model C. Associative mediation | ||||

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → Association between SIC and SPR (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .012 | [.003, .024] | .011 | * |

| Model B′. Alternative sequential mediation | ||||

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SPR Mean (W2) → SIC Mean (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .001 | [.000, .003] | .001 | * |

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → SPR Variability (W2) → SIC Variability (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | .000 | [−.002, .003] b | .000 | |

| Model C′. Alternative associative mediation | ||||

| Cultural Socialization (W1) → Association between SPR and SIC (W2) → Trait Private Regard (W3) | −.004 | [−.019, .009] | −.003 | |

Note. SIC = Situational intragroup contact. SPR = Situational private regard. CI = Confidence interval. We use ab to indicate unstandardized estimates and αβ for standardized estimates.

90% CI for the sequential mediation through SIC variability and SPR variability was [.000, .002].

90% CI for the alternative sequential mediation through SPR variability and SIC variability was [−.002, .003].

p < .10.

p < .05.

Direct mediation of situational private regard: mean and variability

Our first model tested the extent to which the mean level and variability of situational private regard at Wave 2 mediated the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 and trait private regard at Wave 3 (Panel A1 in Figure 2). Parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was linked to higher mean levels and less variability in situational private regard at Wave 2. In turn, higher mean levels and more stable (less variable) private regard across situations at Wave 2 were associated with more positive trait private regard at Wave 3. The mediating effects were significant for both the mean level and variability of situational private regard at Wave 2.

Direct mediation of situational intragroup contact: mean and variability

The second model tested the extent to which the mean level and variability of adolescents’ situational intragroup contact at Wave 2 mediated the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 and trait private regard at Wave 3 (Panel A2 in Figure 2). Parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was associated with greater and more stable intragroup contact across situations at Wave 2. Moreover, adolescents who had higher mean levels of situational intragroup contact at Wave 2 also reported more positive trait private regard at Wave 3. Unlike findings observed for situational private regard, the relation between variability of situational intragroup contact and trait private regard was not significant. The only significant indirect effect was observed for mean level of situational intragroup contact, but not for its variability.

Sequential mediation of situational intragroup contact and situational private regard

The third model tested a sequential mediating pathway from parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 to situational intragroup contact at Wave 2, to situational private regard at Wave 2, and to trait private regard at Wave 3 (Panel B in Figure 2). Regarding the link between parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 and situational intragroup contact at Wave 2, adolescents with greater parental cultural socialization also had greater and more stable intragroup contact across daily situations. Regarding the link between intragroup contact and private regard across situations at Wave 2, adolescents who had higher levels of situational intragroup contact also reported more positive private regard; those who reported more stable situational intragroup contact also had more stable private regard across situations. Regarding the relation between situational private regard at Wave 2 and trait private regard at Wave 3, adolescents whose private regard was higher and more stable across situations also reported more positive trait private regard six months later.

We identified two sequential mediating pathways. The first mediating pathway involved the mean levels of adolescents’ daily experiences: greater parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was associated with higher mean levels of intragroup contact across situations at Wave 2, which in turn was linked to higher mean levels of private regard across situations in the same wave; this, consequently, was related to higher levels of trait private regard at Wave 3. The second mediating pathway involved the variability of adolescents’ daily experiences, which was marginally significant: greater parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was associated with more stable (less variable) intragroup contact across situations at Wave 2, which in turn was associated with more stable (less variable) private regard across situations in the same wave; this, consequently, was linked to higher levels of trait private regard at Wave 3.

Associative mediation of situational association between intragroup contact and private regard

Our final model tested the mediating effect for the association between intragroup contact and private regard across situations at Wave 2 (Panel C in Figure 2). Greater parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was linked to stronger positive associations between intragroup contact and private regard across situations at Wave 2. Moreover, stronger positive associations between intragroup contact and private regard at Wave 2 was associated with higher levels of trait private regard at Wave 3. The mediating effect for this contact-regard association was also significant.

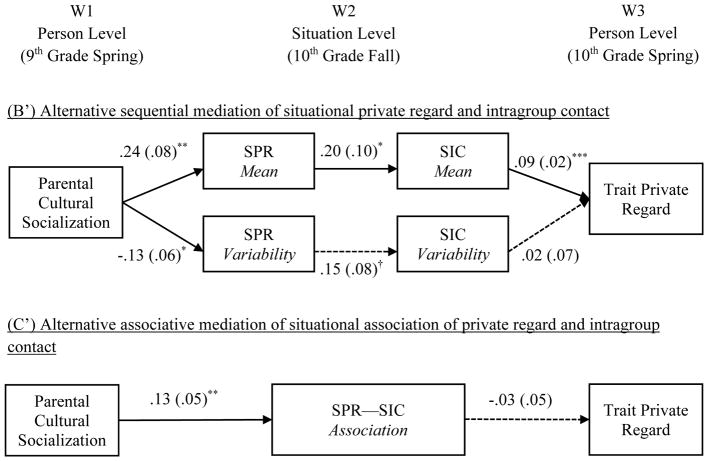

Alternative Mediation between Parental Cultural Socialization and Trait Private Regard

To rule out competing hypotheses, we tested two alternative models for the sequential and relational mediating pathways. We reported direct path coefficients in Figure 3 and mediation effects in the bottom portion of Table 2.

Figure 3.

Standardized coefficient estimates in alternative models for the daily mediating pathways underlying the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and private regard. Standard errors are shown in parentheses. SIC = Situational intragroup contact. SPR = Situational private regard. Significant paths are depicted by solid lines. Non-significant paths are depicted by dash lines. Although not depicted in the figure, the direct effect of Wave 1 parental cultural socialization on Wave 3 trait private regard was also significant. All analyses controlled for adolescent demographics (i.e., cohort, gender, ethnicity/race, and nativity), trait private regard at Wave 1, and the number of assessments of situational variables. †p < .10. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Alternative sequential mediation of situational private regard and situational intragroup contact

We first investigated an alternative, sequential mediating pathway from parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 to situational private regard at Wave 2, to situational intragroup contact at Wave 2, and to trait private regard at Wave 3 (Panel B’ in Figure 3). Adolescents with parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 reported higher mean levels and more stable private regard across situations at Wave 2. Moreover, those who reported higher mean levels of private regard across situations at Wave 2 also had more intragroup contact simultaneously; those who reported more stable private regard across situations also reported more stable intragroup contact, although the effect was only marginally significant. Regarding the link between situational intragroup contact at Wave 2 and trait private regard at Wave 3, adolescents who had greater intragroup contact across situations reported more positive trait private regard subsequently; the variability of intragroup contact across situations was not associated with trait private regard. The mediating pathway through the mean levels of situational private regard and intragroup contact was significant; yet, this indirect effect (αβ = .001) was of a smaller effect size compared to the indirect effect in our hypothesized sequential mediating model (αβ = .006). The mediating pathway through the variability of situational private regard and intragroup contact was not significant at either .05 or .10 levels.

Alternative associative mediation of situational association between private regard and intragroup contact

We then tested an alternative, associative mediating pathway through the association between private regard and intragroup contact across situations at Wave 2 (Panel C’ in Figure 3). Greater parental cultural socialization at Wave 1 was linked to stronger associations between intragroup contact and private regard across daily situations at Wave 2. However, stronger associations between intragroup contact and private regard at Wave 2 was not associated with higher levels of trait private regard at Wave 3. The mediating effect for the contact-regard link was also not significant.

Discussion

Research on the social context of ethnic/racial identity (ERI) development has highlighted the critical role of parental cultural socialization using cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data; however, less is known about how these socialization messages are enacted in adolescents’ daily experiences (Hughes, Watford, & Toro, 2016). To fill in this void, the present study investigated adolescents’ daily feelings towards their ethnicity/race and daily social interactions (i.e., intragroup contact) as mediators of the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and adolescents’ private regard. By integrating longitudinal and experience sampling data, we identified a series of daily mediating mechanisms. First, we identified both direct and sequential mediation through the mean level of adolescents’ intragroup contact and private regard across daily situations. Targeting the changing nature of adolescents’ daily experiences from situation to situation, we also identified a direct mediation effect for the variability in adolescents’ situational private regard and, to some extent, a sequential mediation effect for the variability of their situational intragroup contact and private regard. Finally, moving beyond the concept of variables serving as mediators, we identified an associative mediation in which the dynamic co-occurrence between intragroup contact and private regard across situations served as a mediator for the socialization-trait regard link. These mediating pathways highlight a variety of developmental mechanisms through which parental cultural socialization is enacted in daily dynamics to influence adolescents’ long-term ERI development.

Among the various mediating pathways, we first identified the mean level of adolescents’ situational private regard as a direct mediator between parental cultural socialization and long-term private regard. As hypothesized, adolescents with greater parental cultural socialization were more likely to report more positive private regard across their daily experiences six months later, which in turn were linked to more positive trait private regard another six months later. This mediating pathway is wholly consistent with the extensive literature highlighting the positive effect of parental cultural socialization on adolescents’ ERI (Hughes et al., 2006, 2016). More importantly, this finding elucidates how children’s perceptions of parental messages are enacted in daily life to influence their ERI development.

In addition to adolescents’ daily feelings, we also identified the mean level of adolescents’ daily social interactions, in the form of contact with same-ethnic others, as a mediator underlying the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and trait private regard. Adolescents who had greater parental cultural socialization also had more daily contact with same-ethnic others, on average, and this contact, in turn, was associated with more positive private regard, both in their daily lives and in the long term. While prior research has documented the promotive effect of intragroup contact for adolescents’ private regard (Yip et al., 2013), the present study identified parental cultural socialization as a contextual factor that may set this dynamic in motion. Adolescents reporting more parental cultural socialization likely have parents who support and encourage same-ethnic contacts and friendships (Updegraff et al., 2010). Parents may also create opportunities for adolescents to interact with same-ethnic others, such as participating in ethnic and cultural activities, choosing neighborhoods with a concentration of co-ethnics, or placing their children in schools with same-ethnic peers. While research on family-peer linkages has stressed the active role parents play in shaping adolescents’ social contexts and interactions (Brown & Bakken, 2011; McDowell & Parke, 2009), there has been limited work in understanding such linkages in cultural and ethnic/racial contexts (Mistry & Wu, 2010). The present study contributes to this literature by demonstrating the parental influences on adolescents’ daily social experiences related to ethnicity and race.

In addition to these important theoretical contributions, the present study also highlights some novel approaches to understanding adolescents’ daily experiences. One such approach is the investigation of variability in adolescents’ daily experiences as a developmentally meaningful construct. Specifically, variability of adolescents’ private regard across situations functioned as a direct mediator for the longitudinal effect of parental cultural socialization on trait private regard: adolescents with greater parental cultural socialization reported more stable ERI private regard feelings across situations, which in turn was associated with more positive trait private regard in the long term. We also observed some evidence for the variability of adolescents’ situational intragroup contact and private regard as sequential mediators: those with greater parental cultural socialization had more stable intragroup contact across situations, which in turn led to more stable ethnic feelings in these situations, and consequently more positive trait private regard in the long term. Although the literature on ERI development has recognized daily variations in adolescents’ ethnic feelings (Kiang et al., 2006; Yip & Fulgni, 2002), much less is known about where such variability comes from and how it influences ERI development. The present study provided insights to both questions. In terms of the sources of variability, our finding suggests that the changing nature of adolescents’ social interactions from one situation to another contributes to the variability of their ethnic feelings. In contrast, family contexts may function as a source of stability in shaping adolescents’ social interactions and feelings in everyday life. In line with research stressing the role of family structure and routines in creating a sense of stability (Fiese, Foley, & Spagnola, 2006), as well as the negative impact of chaos on adjustment (Evans, Gonnella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005), our findings demonstrate how adolescents’ family settings and social interactions contribute to stability and change in ERI in adolescents’ daily lives.

The current study also provides unique insight into how the stability of adolescents’ feelings about their ethnic/racial group contributes to their ERI development over time. Prior research has highlighted mood variability as an indicator of instability and vulnerability compromising individuals’ well-being (see Houben et al., 2015 for a meta-analysis). Similarly, adolescents who exhibited daily variability in their ethnic feelings may experience challenges in maintaining a stable and secure sense of self, and these challenges likely impede the development of positive trait private regard in the long term. In contrast, those who feel consistently positive about their ethnic/racial group across situations are better positioned to maintain these positive feelings over time. While variability is associated with compromised developmental outcomes in the present study, our other work shows that variability can also promote development for other dimensions of ERI. For example, ethnic/racial minority adolescents who reported more variable awareness of their ethnicity/race (i.e., salience) across situations engaged in greater ERI exploration activities (Wang, Douglass, & Yip, 2016). This promising area of research suggests that the affective (e.g., private regard) versus cognitive (e.g., salience) components of ERI at the level of the specific situation may have important yet different developmental implications. These findings together highlight the value of examining variability in various ERI domains to better understand the process of identity development.

In addition to the investigation of variability in adolescents’ daily experiences, the current study offers another notable analytical contribution by introducing associative mediation, a novel analytical approach to unpack how the association between daily experiences is related to development over time. This is an approach that has not yet been observed in developmental science. In the current study, we focus on situational associations between intragroup contact and private regard as a mediator for the longitudinal link between parental cultural socialization and trait private regard. Specifically, adolescents with greater parental cultural socialization were more likely to have a strong, positive daily association between intragroup contact and private regard, which, in turn, was linked to positive trait private regard in the long term. Adolescents reporting greater parental cultural socialization likely received more positive messages about their heritage culture and ethnic/racial group; as a result, we hypothesized that they would be more likely to feel better about their ethnic/racial group membership when they spent time with same-ethnic others. In other words, these adolescents would exhibit a stronger association between intragroup contact and private regard in a particular situation. Methodologically, this first portion of the associative mediation (i.e., the path linking parental cultural socialization to contact-regard association) is equivalent to a cross-level interaction (Preacher et al., 2015), in which parental cultural socialization (person-level) interacted with adolescents’ situational intragroup contact to influence situational private regard. Yet, our associative mediation approach represents a conceptual departure from cross-level interactions, as it highlights the developmental implications of the random slope (i.e., contact-regard association). Specifically, this repeated co-occurrence of intragroup contact and private regard subsequently accumulates across situations to promote long-term trait private regard. ERI development is not only an accumulation of isolated daily events (e.g., contact with same-ethnic others or private regard), but also the result of dynamic associations between these everyday experiences. Indeed, theoretical work has highlighted the developmental importance of interrelated events that occur repeatedly over time (Elder et al., 2015). This assertion is further supported with empirical observations on stress reactivity where the daily association between stress and negative mood (i.e., stress reactivity) predicts subsequent psychological well-being (Charles et al., 2013; Mandel et al., 2015). The investigation of associative, or strength-of-relationship, mediation is made possible by intensive longitudinal data measuring individual experiences across situations, highlighting the value of experience sampling approaches for elucidating nuanced, dynamic pathways of development.

While the present study contributes to the theoretical, conceptual, and analytical literature on the association between parental cultural socialization and private regard, findings should also be interpreted with caveats. First, we use the term “trait private regard” to distinguish it from our situation-level measure. However, we acknowledge research observing developmental changes in private regard over the life course (Hughes, Way, & Rivas-Drake, 2011; Rivas-Drake & Witherspoon, 2013). Our findings also highlight the developmental mechanisms underlying the change in this “trait” construct over time. In addition, the present study assessed parental cultural socialization as a stable family context that underpins adolescents’ daily experiences. However, recent work using observational methods has identified the dynamic ways in which parents adapt their messages based on adolescents’ experiences with discrimination (Smith-Bynum, Lambert, English, & Ialongo, 2014). As such, future research would benefit from employing methodological approaches that consider variability in parental cultural socialization over time and space. Relatedly, research has observed that parental cultural socialization varies across ethnic/racial groups in important and meaningful ways (Hughes, 2003), yet the current study was unable to explore differences across these groups due to the limited sample size. Moreover, although our sample was collected from schools of varying ethnic/racial composition, the study was not sufficiently powered to explore the moderating effect of school context (e.g., one participating school only had 36 students in the analytic sample). Future work with larger samples is needed to continue this line of work. Finally, the present study assessed parental cultural socialization and trait private regard using adolescent reports, which may introduce shared method variance to the observed relation between parental cultural socialization and trait private regard over time. While our analyses controlled for earlier levels of trait private regard, future work using data from multiple informants (e.g., parent reported cultural socialization) would be ideal.

Despite these limitations, this study makes an important and unique contribution to the study of how parents’ messages about race are enacted in adolescents’ daily lives, and the psychological significance of these messages in shaping how adolescents feel about themselves and members of their ethnic/racial group. The novel combination of person- and situation-level data helped to elucidate developmental mechanisms and processes that have not been uncovered in existing survey research methods. We hope the present study can provide a framework for future research exploring the diverse pathways through which development occurs in adolescents’ daily experiences.

Acknowledgments

Author Note: This research was supported by a Grant awarded to the fourth author and J. Nicole Shelton of Princeton University from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1 R01 HD055436). The first author was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (1354134) awarded to Tiffany Yip.

Contributor Information

Yijie Wang, Michigan State University.

Heining Cham, Fordham University.

Meera Aladin, Fordham University.

Tiffany Yip, Fordham University.

References

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The bioecological model of human development. In: Lerner RM, Damon W, Lerner RM, Damon W, editors. Handbook of child psychology (6th ed.): Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Bakken JP. Parenting and peer relationships: Reinvigorating research on family-peer linkages in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00720.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charles S, Piazza JR, Mogle J, Sliwinski MJ, Almeida DM. The wear and tear of daily stressors on mental health. Psychological Science. 2013;24:733–741. doi: 10.1177/0956797612462222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen TC, Barrett LF, Bliss-Moreau E, Lebo K, Kaschub C. A practical guide to experience-sampling procedures. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2003;4:53–78. doi: 10.1023/A:1023609306024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE. Identity formation and self-development in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 1: Individual bases of adolescent development. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009. pp. 266–304. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass S, Wang Y, Yip T. The everyday implications of ethnic-racial identity processes: Exploring variability in ethnic-racial identity salience across situations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45:1396–1411. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Shanahan MJ, Jennings JA. Human development in time and place. In: Lerner RM, Bornstein MH, Leventhal T, editors. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, Volume 4, Ecological settings and processes. 7. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2015. pp. 1–49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Morse E. Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;21:54–64. doi: 10.1037/a0037820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Gonnella C, Marcynyszyn LA, Gentile L, Salpekar N. The roles of chaos in poverty and children’s socioemotional adjustment. Psychological Science. 2005;16:560–565. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH, Foley KP, Spagnola M. Routine and ritual elements in family mealtimes: Contexts for child well-being and family identity. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2006;111:67–89. doi: 10.1002/cd.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Yip T, Tseng V. The impact of family obligation on the daily activities and psychological well-being of Chinese American adolescents. Child Development. 2002;73:302–314. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to meditaion, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández MM, Conger RD, Robins RW, Bacher KB, Widaman KF. Cultural socialization and ethnic pride among Mexica-origin adolescents during the transition to middle school. Child Development. 2014;85:695–708. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben M, Van Den Noortgate W, Kuppens P. The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141:901–930. doi: 10.1037/a0038822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Chen L. When and what parents tell children about race: An examination of race-related socialization among African American families. Applied Developmental Science. 1997;1:200–214. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads0104_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, McGill RK, Ford KR, Tubbs C. Black youths’ academic success: The contribution of racial socialization from parents, peers, and schools. In: Hill NE, Mann TL, Fitzgerald HE, editors. African American children and mental health: Development and context, prevention and social policy. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger/ABC-CLIO; 2011. pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Watford JA, Del Toro J. A transactional/ecological perspective on ethnic-racial identity, socialization, and discrimination. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 2016;51:1–41. doi: 10.1016/bs.acdb.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Way N, Rivas-Drake D. Stability and change in private and public ethnic regard among African American, Puerto Rican, Dominican, and Chinese American early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:861–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00744.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Fuligni AJ. Ethnic identity in context: variations in ethnic exploration and belonging within parent, same-ethnic peer, and different-ethnic peer relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;38:732–743. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9278-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, Gonzales-Backen M, Witkow MR, Fulgni AJ. Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Development. 2006;75:1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM. Time use as cause and consequence of youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2015;9:20–25. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH, Moneta G, Holmbeck G, Duckett E. Changes in adolescents’ daily intercations with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:744–754. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel T, Dunkley DM, Moroz M. Self-Critical perfectionism and depressive and anxious symptoms over 4 years: The mediating role of daily stress reactivity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62:703–717. doi: 10.1037/cou0000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell DJ, Parke RD. Parental correlates of children’s peer relations: An empirical test of a tripartite model. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:224–235. doi: 10.1037/a0014305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry J, Wu J. Navigating cultural worlds and negotiating identities: A conceptual model. Human Development. 2010;53:5–25. doi: 10.1159/000268136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki M, Tinsley BJ, Chao RK, Unger JB. An ecological perspective on smoking among asian american college students: The roles of social smoking and smoking motives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:514–523. doi: 10.1037/a0012964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Burks VM, Carson JL, Neville B, Boyum LA. Family-peer relationships: A tripartite model. In: Parke RD, Kellam SG, editors. Exploring family relationships with other social contexts. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Romero I, Nava M, Huang D. The role of language, parents, and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30:135–153. doi: 10.1023/A:1010389607319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes AF, Slater MD, Snyder LB, editors. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 13–54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ. Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological Methods. 2015;21:189–205. doi: 10.1037/met0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods. 2010;15:209–233. doi: 10.1037/a0020141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Syed M, Umaña-Taylor A, Markstrom C, French S, Schwartz SJ, Lee R. Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic–racial affect and adjustment. Child Development. 2014;85:77–102. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Witherspoon D. Racial identity from adolescence to young adulthood: Does prior neighborhood experience matter? Child Development. 2013;84:1918–1932. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, Umaña-Taylor A, Smith EP, Johnson DJ. Cultural processes in parenting and youth outcomes: examining a model of racial-ethnic socialization and identity in diverse populations. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:106–111. doi: 10.1037/a0015510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Yip T, Sellers RM. A longitudinal examination of racial identity and racial discrimination among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2009;80:406–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, Smith MA. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and constuct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:805–815. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith MA, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, Douglass S, Garcia LR, Yip T, Trail ET. Feeling (mis) understood and intergroup friendships in interracial interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2014;40:1193–1204. doi: 10.1177/0146167214538459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bynum MA, Lambert SF, English D, Ialongo NS. Associations between trajectories of perceived racial discrimination and psychological symptoms among African American adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:1049–1065. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AB, MacKinnon DP, Tein JY. Tests of the three-path mediated effect. Organizational Research Methods. 2007;11:241–269. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?: And other conversations about race. New York: Basic Books; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. Monte Carlo confidence intervals for complex functions of indirect effects. Structural Equation Modeling. 2016;23:194–205. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2015.1057284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: Examining the role of social context. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, … Seaton E. Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Kim JY, Killoren SE, Thayer SM. Mexican American parents’ involvement in adolescents’ peer relationships: Exploring the role of culture and adolescents’ peer experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:65–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Benner AD. Cultural socialization across contexts: Family–peer congruence and adolescent well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45:594–611. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Douglass S, Yip T. Longitudinal relations between ethnic/racial identity process and content: Exploration, commitment, and salience among diverse adolescents. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/dev0000388. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner TS. Ecocultural understanding of children’s developmental pathways. Human Development. 2002;45:275–281. doi: 10.1159/000064989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T. Sources of situational variation in ethnic identity and psychological well-being: A Palm Pilot study of Chinese American students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(2):1603–1616. doi: 10.1177/0146167205277094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T. Ethnic identity in everyday life: The influence of identity development status. Child Development. 2014;85:205–219. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Douglass S. The application of experience sampling approaches to the study of ethnic identity: New developmental insights and directions. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7(4):211–214. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Douglass S, Shelton JN. Daily intragroup contact in diverse settings: Implications for Asian adolescents’ ethnic identity. Child Development. 2013;84:1425–1441. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Fulgni AJ. Daily variation in ethnic identity, ethnic behaviors, and psychological well-being among American adolescents of Chinese descent. Child Development. 2002;73:1557–1572. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip T, Seaton EK, Sellers RM. Interracial and intraracial contact, school-level diversity, and change in racial identity status among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2010;81:1431–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]