Abstract

Habits have been studied for decades, but it was not until recent years that experiments began to elucidate the underlying cellular and circuit mechanisms. The latest experiments have been enabled by advances in cell-type specific monitoring and manipulation of activity in large neuronal populations. Here we will review recent efforts to understand the neural substrates underlying habit formation, focusing on rodent studies on corticostriatal circuits.

Although actions are usually governed by an explicit representation of the desired outcome, many behaviors, commonly called habits, do not appear to rely on such representations. Intuitively, habits are adaptive because they can free up attentional resources and automatize routine behavior, yet they can also be inflexible and even disruptive when environmental contingencies change. A striking example of the latter was given by James in 1890 in his classic chapter on habits: a discharged veteran, who upon hearing “Attention!” brought his hands down to assume a military posture, and in so doing dropped the dinner he was carrying [1].

The key difference between habitual versus goal-directed actions is not the motor output per se, but how the action is generated. As noted by James, in voluntary actions, the outcome representation can somehow generate the behavior (ideomotor), whereas in habits, the triggering event appears to be the discriminative stimulus or the feedback associated with the completion of the previous behavior. To study this distinction experimentally, Dickinson and colleagues developed a clever approach. They trained rats to press a lever for food reward [2,3]. The reward outcome can then be ‘devalued’, whether by satiety or by taste aversion induction, so that the rats will no longer consume it voluntarily; they can then be tested in the absence of reward feedback in the devalued state, in order to measure the effect of devaluation on performance and the extent to which the generation of the action is based on outcome expectancy. Using these methods, it was found that, in some animals, devaluation drastically reduced performance relative to non-devalued condition, whereas in others it had little effect, i.e. lever pressing was just as likely as in the non-devalued state. Thus there appear to be two distinct modes of action control that can be experimentally dissociated. According to Dickinson, actions that are clearly reduced by devaluation are goal-directed, whereas actions that persisted in spite of the devalued outcome are habitual. These operational definitions created a fruitful framework that enabled the design of experiments quantifying habitual and goal-directed behavior. Using this framework, studies have also shown that the major factors contributing to habit formation are prolonged training and certain schedules of reinforcement (see Box 1) [2–4].

Box 1. Glossary of technical terms.

Reinforcement schedule and feedback function

Reinforcement is anything that, when presented after a behavior, will increase the probability that this behavior is repeated in the future. The reinforcement schedule determines how the reinforcement is delivered. Feedback function is a more general term describing input as a function of output, e.g. the rate of reward feedback to the rate of the instrumental action. In ratio schedules, a certain number of lever presses will yield a reinforcer. In interval schedules, some time interval must elapse before another reinforcer becomes available, so the feedback function is less linear.

Devaluation

After training with a specific food reward, the reward ‘value’ can be reduced so that the animal will no longer consume it. This can be done by pre-feeding or by inducing taste aversion. A brief probe test is then conducted to test how the instrumental action is generated. If it is based on explicit representation of the outcome, then performance should be reduced following devaluation. If not, devaluation should not have any effect.

Contingency degradation

Another strategy used to assess the status of the action is to alter the instrumental contingency or feedback function. Most commonly, the probability of reward delivery is set to be the same regardless of lever pressing. Habitual performance is less likely to be affected by degradation.

Endocannabinoid dependent long-term depression (eCB LTD)

a prominent form of LTD found at both glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses in the striatum. The site of induction for eCB LTD is in the postsynaptic neuron, but endocannabinoids act as retrograde messengers that travel to the presynaptic terminal, resulting in long-lasting reduction in the probability of presynaptic transmitter release.

AMPA/NMDA ratio

The ratio between evoked excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) through α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs) and EPSC through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs). At most glutamatergic synapses, both AMPARs and NMDARs are expressed postsynaptically, but their synaptic conductances have different time constants and voltage dependencies. NMDARs are also heavily implicated in synaptic plasticity due to their high calcium permeability. AMPA/NMDA ratio is a common measure of synaptic plasticity as many glutamatergic synapses show AMPAR insertion as a molecular mechanism for LTP expression and AMPAR endocytosis for LTD expression.

Studying the neural substrates of habits

The striatum, as the main input nucleus of the basal ganglia (BG), has long been implicated in procedural learning [5–8]. Lesion and inactivation studies using the behavioral assays discussed above further established a crucial role of the striatum, suggesting that goal-directed actions require the dorsomedial striatum (DMS) whereas habits require the dorsolateral striatum (DLS) [9–12].

These initial findings raise several questions. Are separate neural circuits driving habitual and goal-directed performance? Since the striatum itself contains different cell populations that can be distinguished by connectivity and expression of receptors for neuromodulators, what are the local circuit mechanisms that change during habit formation? Recent studies taking advantage of new tools for selective monitoring and perturbation of neural activity have begun to address these questions.

Region-specific coordination of habitual behavior

Striatal subregions are known to receive inputs from distinct cortical regions [13,14]. Gremel et al (2016) employed a within-subject design using distinct discriminative stimuli for two different reinforcement schedules to promote goal-directed or habitual behavior (see Box 1). They found that chemogenetically inhibiting excitatory projections from orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) to DMS promoted habitual behavior in otherwise goal-directed mice [15]. Similar effects were observed after DMS lesion or inactivation [16]. Previous studies implicated endocannabinoid signaling in long-term depression (LTD, Box 1) and in habit formation [17–19]. Gremel et al (2106) tested whether endocannabinoid signaling through its receptor, CB1R, on DMS-projecting OFC neurons was required for the transition from goal-directed to habitual behavior. They found that deleting CB1Rs specifically from DMS-projecting OFC neurons prevented the transition from goal-directed to habitual behavior [15]. One caveat is that CB1R deletion can also alter presynaptic function at other sites that OFC afferents target. It is unclear whether the DMS-projecting OFC neurons also project to other areas, and if so what the contributions of these other areas are.

Since OFC neurons have been previously associated with reward-outcome representations [20,21], a specific depression of OFC-DMS transmission during habit formation might reduce the influence of such representations on action selection. The study by Gremel et al is therefore in accord with prior studies [16,22] showing that disrupting DMS output alone could promote habitual control.

Striatal direct and indirect pathway plasticity in habits

Besides potential competition between different striatal regions, within a striatal region there are two classes of projection neurons with opponent influences on BG output [23]. Although the relative contributions of these two pathways remain controversial [24], pathway-specific differences in both DMS and DLS have been identified as a function of behavioral training. In the DMS, striatal A2A adenosine receptors (A2ARs) have been manipulated to understand contributions of the indirect pathway to instrumental behavior [25–27]. A2ARs are Gs-coupled receptors selectively expressed in striatal indirect pathway neurons (iSPNs). A2AR activation can promote iSPN activity and reduce net output from a given striatal region. Using rhodopsin-A2AR chimeras, Li et al (2016) found that optogenetic activation of A2ARs in DMS iSPNs suppresses expression of goal-directed actions, as measured by outcome devaluation. In contrast, knockdown of A2ARs in the same area, which is expected to increase DMS output, also increased goal-directed control [26]. These results suggest that the degree of iSPN activity can determine the contribution of the DMS to instrumental action selection.

So far we have discussed recent results involving manipulations and observations in the DMS. Yet DLS has also been implicated in habit formation [22]. One question is whether habit emerges from reduced DMS output or increased DLS output. Lesion and inactivation results suggest that both could be involved. This is supported by recent studies on pathway-specific changes in DLS activity.

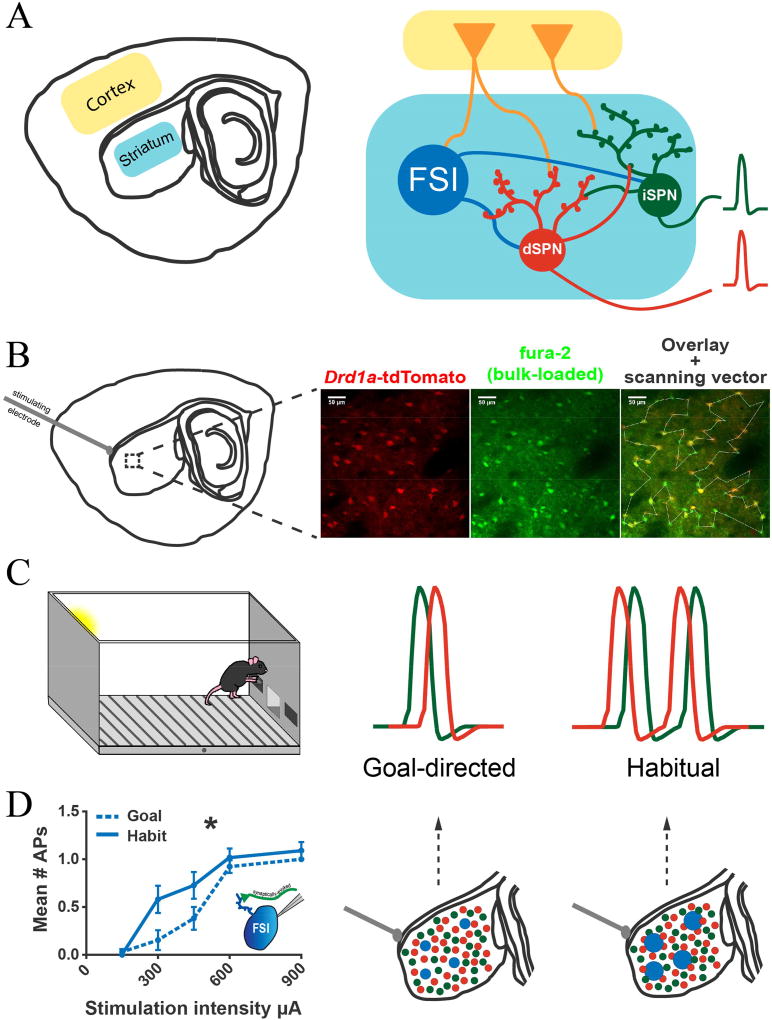

O’Hare & Ade et al (2016) reported DLS plasticity in habit using an approach that measured striatal circuit outputs (Fig. 1). Mice were trained in a lever press task and their degree of habitual performance was measured prior to sacrifice and preparation of DLS brain slices. Striatal output (e.g. action potential firing by projection neurons) was evoked by electrical stimulation of cortical inputs and measured using transgenic cell-type reporters, a calcium indicator dye, and two-photon laser scanning microscopy [28,29]. The investigators found that the DLS corticostriatal input/output function was shaped by training and predicted the degree of habitual control in individual mice. Habitual behavior correlated with larger evoked amplitudes of SPN calcium transients in both the direct (dSPNs) and indirect (iSPNs) pathways, but not with spike probability [29], indicating that the increase in calcium transient amplitude likely reflects increased SPN burst firing. On the other hand, weakening of inputs to the direct pathway predicts suppression of the same habit. Given previous work suggesting that the DLS is also involved in habit extinction [30], depression of corticostriatal inputs to the direct pathway could be a key underlying mechanism.

Figure 1. Probing circuit- and microcircuit-level striatal adaptations in habit formation.

A) Schematic of corticostriatal circuitry. Left: Illustration of a parasaggital brain section containing the dorsolateral region of the striatum and one of its main inputs, the cortex. Right: Simplified diagram to indicate that cortical projections directly excite striatal projection neurons (SPNs) belonging to the direct and indirect pathways as well as local striatal interneurons such as the fast-spiking interneuron (FSI). Direct and indirect pathway SPN firing represent striatal output, indicated by the red and green action potential waveforms, far right. B) Dual pathway Imaging of Striatal Circuit Output (DISCO). Left: Corticostriatal afferent fibers are electrically stimulated to drive action potential firing in large populations of SPNs and striatal interneurons. Right: Using a transgenic reporter mouse with high sensitivity and specificity for dSPNs and a calcium indicator dye (fura-2, AM) that fluoresces at basal calcium levels, action potential firing is monitored in dSPNs and iSPNs simultaneously using two-photon laser scanning microscopy. C) Evoked DLS circuit output properties in individual mice correlate with behavior across the goal-directed to habitual spectrum. In mice trained in a lever press task, habit was predicted by increases in evoked output of both direct and indirect pathway neurons. Additionally, whereas in goal-directed mice iSPNs tend to respond to cortical excitation before dSPNs, this timing bias was reversed in habitual animals, i.e. dSPNs fired earlier. D) Left: Using lever press training as in (C) and electrophysiological recordings, FSIs from habitual mice were found to fire more readily than those from goal-directed mice in response to afferent stimulation. Right: proposed model for FSI role in shaping striatal output in habit, based on additional pharmacological and optogenetic FSI inhibition experiments. Enhancing FSI activity (indicated by larger blue dots) is assumed to be responsible for the habit-predictive features of striatal projection neuron firing identified in (C).

In addition, a shift in the relative timing to fire between dSPNs and iSPNs (Fig. 1C) also strongly correlated with the degree of habitual responding [29]. This is in agreement with in vivo electrophysiological measures of output timing from the direct and indirect pathways. These studies show that the particular pathway in which activity is first detected predicts behavior in an action cancellation task [31]. A subsequent study by the same team identified a specific inhibitory pathway from arkypallidal neurons to the striatum as responsible for action cancellation. Activation of this pathway, however, failed to interrupt those actions with the shortest latencies [32]. These observations predict that plasticity in the DLS accompanying habit formation would make action cancellation less likely, possibly by giving the direct pathway a “headstart” in initiating behavior and shortening reaction times [33].

Since dSPNs and iSPNs are concurrently activated with action initiation [34,35], together the above findings suggest that habit learning reconfigures the DLS circuitry to be more responsive to descending cortical commands, which might represent antecedent stimuli or the completion of the previous component in a sequence. Indeed, previous work has shown that cortical inputs to DLS carrying representations of discriminative stimuli are selectively potentiated in an auditory discrimination task [36].

In a more recent study, O’Hare et al identified that striatal fast spiking interneurons (FSIs) modulate the “habit-predictive” features of striatal output, indicating a potential cellular mechanism for the previously described circuit plasticity[37]. These GABAergic interneurons, which can be identified by their expression of parvalbumin, are more numerous in the DLS than in any other striatal region [38,39]. Habit training was accompanied by long-lasting increases of FSI excitability (Fig. 1) and FSI activity was necessary for habitual lever pressing. Interestingly, although FSIs are commonly known to inhibit SPNs, O’Hare et al discovered that their effects on SPNs are more complex than previously assumed. While FSIs exert a strong inhibitory effect on many SPNs, FSIs appear to have an excitatory effect on a select population of SPNs that show high burst firing. This selective potentiation may be akin to a winner-take-all “focusing” mechanism that increases the signal-to-noise ratio in corticostriatal transmission. The population of highly active SPNs would be facilitated while less active SPNs would be suppressed by the inhibition. This finding suggests a mechanism for action selection that activates the appropriate combination of SPNs while suppressing irrelevant or antagonistic SPNs. The demonstration of striatal FSI plasticity also suggests that multiple sites of plasticity in the striatum may dynamically interact to shape habitual behavior.

Although recent studies have identified select DMS inputs from OFC as a significant modulator of habitual behavior, the identity of specific DLS inputs that undergo plasticity during habit formation is not yet known. The particular subregion of DLS showing habit-related plasticity in the study by O’Hare & Ade et al (2016) is notable for receiving massive inputs from primary sensorimotor cortices [13–14]. Interestingly, selective plasticity in cortical DLS inputs from M2 has recently been identified in serial order learning, which requires a specific sequence of actions to earn rewards. The DLS has long been implicated in sequential behavior, whether innately specified sequences like grooming [40], or skills like learning to stay on a rotarod [41]. The acquisition of a simple AB sequence requires the DLS [42] and to a lesser extent the secondary motor cortex (M2)[43]. Rothwell et al (2015) found that M2-DLS glutamatergic synapses were strengthened with learning, and specifically at synapses onto dSPNs. These results also suggest that the AB sequence is initiated as a single unit by the M2-DLS projections. In accord with previous lesion studies, they also highlight the potential for overlapping circuitry between habit formation and learning of behavioral sequences. They support the idea that habit formation often involves linking diverse components and turning it into a single unit [1,6].

From kinematics to habits

One difficulty in understanding the contribution of the DLS to habit formation is that neurons in this region also show strong correlations with movement kinematics, and its output is thought to be critical for voluntary movements [44–46]. It should be noted, however, that the role of the DLS in performance is not incompatible with its contribution to habit formation. These views can be reconciled if we consider the striatal output as orders to achieve high level movement parameters, especially the rate at which a given behavioral sequence is executed or movement velocity. These are integrated at the level of the basal ganglia output nuclei to yield detailed position parameters for movements [47]. Learning, including habit formation, would involve adaptive modification of these descending orders, especially at the corticostriatal synapse. Such a model predicts that the kinematic representations in the DLS could change with learning as new SPNs are recruited [48].

Recently, Rueda-Orozco et al (2015) asked how kinematic representations in the DLS changed with habit formation, using a task in which rats used contextual cues to precisely time their acceleration into a “goal zone” at the front of a treadmill and thus obtain a sucrose reward. Contingency degradation and outcome devaluation were used to assess how habitual the rats were. They found that DLS activity represented position and velocity on the treadmill. Interestingly, correlations between SPN activity and kinematics were stronger in habitual subjects and steadily increased with training up to and well beyond the point of asymptotic performance [49]. Consistent with a role for DLS in performance of stereotyped sequences, pharmacological silencing of this brain region increased variability in the timing and magnitude of acceleration when rats made their dash for the goal zone. These results suggest that, with training, DLS takes on a more active role in controlling kinematic features of a learned behavior.

Summary and Outstanding Questions

Recent work on habit formation illustrates the power of combining appropriate behavioral assays and new tools in imaging, electrophysiology, and cell-type specific manipulations of neural activity. Studies have begun to elucidate the circuit and cellular mechanisms for habits and how this circuitry interacts with circuitry for goal-directed behavior.

Although a coherent model of habit formation has yet to be developed, converging evidence allows several generalizations. First, pathway-specific findings in the striatum suggest that plasticity favoring the direct pathway (whether by weakening indirect and/or strengthening direct pathway activity) can promote different modes of behavioral control depending on the striatal region affected. Such a change in the DMS can promote goal-directed actions, e.g. acquisition of goal-directed actions has been associated with corticostriatal synaptic changes favoring direct pathway neurons [50]. On the other hand, increasing indirect pathway activity in the DMS promotes habitual performance, presumably through the DLS circuit [26]. In the DLS, by contrast, habit correlates with shorter latencies of direct pathway neurons in comparison to indirect pathway neurons. Moreover, suppression of a learned habit is predicted solely by weakening of direct pathway output [29].

Recent studies also suggest that brain regions upstream of the BG, especially the cerebral cortex, can dictate which striatal circuit, DMS or DLS, will be responsible for generating actions. For example, the contribution of DMS in action selection appears to be weakened with habit formation as a result of reduced excitatory synaptic strength in the OFC-DMS input [15]. On the other hand, the M2-DLS pathway is strengthened during serial order learning [51]. Although there is significant overlap in the neural circuit for habits and that underlying sequential behavior, it is important to keep in mind that not all highly trained behavioral sequences are habits, as the initiation of many of these motor routines can be highly goal-directed. The execution of individual components of a complex sequence could share key mechanisms with habitual performance. Thus, a distinction must be made between the initiation and termination of a learned behavioral sequence and the execution of individual elements within the sequence. Even for highly trained sequences, such as riding a bike, the initiation could still be entirely goal-directed and governed by outcome expectancy. In normal behaviors, there could be frequent switching between goal-directed and habitual modes of action generation or even simultaneous engagement of the underlying circuits.

Recent modeling work has shown that, as a network of recurrently connected inhibitory units, the striatum is capable of generating sequential neural activity patterns with adjustable temporal scaling of the sequence [52]. The plasticity mechanism required in such a network is in accord with known striatal LTD at inhibitory synapses [53]. Moreover, once acquired sequential behavior can be generated even when the excitatory drive is no longer present [52], suggesting that cortical and other inputs may not required to trigger each component of a sequence, but only at the start and termination [54]. This possibility remains to be tested.

While recent studies have led to significant insights into the synaptic and circuit mechanisms underlying habit formation, they have also revealed major gaps in our understanding. What is the role of other afferents to the striatum, e.g. thalamostriatal projection, in driving DLS and DMS output? How do outputs from different striatal regions affect downstream basal ganglia output nuclei to generate habitual behavior? What, if any, is the role of cortex in long-term storage of habitual repertoires? These questions remain to be addressed. What is clear from the foregoing discussion is that an integrative approach involving multiple levels of analysis – including single synapses, local networks, and in vivo dynamics – will be needed to clarify the relationship between neuronal plasticity in the basal ganglia and habitual behavior.

Highlights.

Goal-directed and habitual modes of behavioral control can be behaviorally dissociated

Recent work reveals distinct contributions of striatal cell populations to goal-directed actions and habits

Corticostriatal plasticity as well as striatal interneuron plasticity are implicated in habit formation

Habitual actions and learned behavioral sequences share some common mechanisms

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the following sources of funding: NS064577 (N.C.), ARRA supplement to NS064577 (N.C.), AA021075 and DA040701 (H.Y.), McKnight Foundation (N.C., H.Y.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not have any conflict of interest

References

- 1.James W. The principles of psychology. Vol. 1. New York: Henry Holt; 1890. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams CD, Dickinson A. Instrumental responding following reinforcer devaluation. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1981;33:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams CD. Variations in the sensitivity of instrumental responding to reinforcer devaluation. Quarterly journal of experimental psychology. 1982;33b:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derusso AL, Fan D, Gupta J, Shelest O, Costa RM, Yin HH. Instrumental uncertainty as a determinant of behavior under interval schedules of reinforcement. Front Integr Neurosci. 2010;4 doi: 10.3389/fnint.2010.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saint-Cyr J, Taylor AE, Lang A. Procedural learning and neostriatal dysfunction in man. Brain. 1988;111:941–960. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graybiel AM. The basal ganglia and chunking of action repertoires. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1998;70:119–136. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jog MS, Kubota Y, Connolly CI, Hillegaart V, Graybiel AM. Building neural representations of habits. Science. 1999;286:1745–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowlton BJ, Mangels JA, Squire LR. A neostriatal habit learning system in humans [see comments] Science. 1996;273:1399–1402. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin HH, Knowlton BJ. The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:464–476. doi: 10.1038/nrn1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh SW, Harris JA, Ng L, Winslow B, Cain N, Mihalas S, Wang Q, Lau C, Kuan L, Henry AM. A mesoscale connectome of the mouse brain. Nature. 2014;508:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature13186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace ML, Saunders A, Huang KW, Philson AC, Goldman M, Macosko EZ, McCarroll SA, Sabatini BL. Genetically Distinct Parallel Pathways in the Entopeduncular Nucleus for Limbic and Sensorimotor Output of the Basal Ganglia. Neuron. 2017;94:138–152.e135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin HH, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. Inactivation of dorsolateral striatum enhances sensitivity to changes in the action-outcome contingency in instrumental conditioning. Behav Brain Res. 2006;166:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGeorge AJ, Faull RL. The organization of the projection from the cerebral cortex to the striatum in the rat. Neuroscience. 1989;29:503–537. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hintiryan H, Foster NN, Bowman I, Bay M, Song MY, Gou L, Yamashita S, Bienkowski MS, Zingg B, Zhu M, et al. The mouse cortico-striatal projectome. Nat Neurosci. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nn.4332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 15.Gremel CM, Chancey JH, Atwood BK, Luo G, Neve R, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Lovinger DM, Costa RM. Endocannabinoid modulation of orbitostriatal circuits gates habit formation. Neuron. 2016;90:1312–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.043. Shows that the projection from orbitofrontal cortex to dorsomedial striatum plays an important role in gating the expression of habits, and that endocannabinoid-dependent LTD at this corticostriatal synapse can promote habitual behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin HH, Ostlund SB, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. The role of the dorsomedial striatum in instrumental conditioning. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:513–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilario MRF, Clouse E, Yin HH, Costa RM. Endocannabinoid signaling is critical for habit formation. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2007;1:6. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.006.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazzaro C, Greco B, Cerovic M, Baxter P, Rubino T, Trusel M, Parolaro D, Tkatch T, Benfenati F, Pedarzani P, et al. SK channel modulation rescues striatal plasticity and control over habit in cannabinoid tolerance. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:284–293. doi: 10.1038/nn.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerdeman GL, Ronesi J, Lovinger DM. Postsynaptic endocannabinoid release is critical to long-term depression in the striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nn832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schultz W, Tremblay L, Hollerman JR. Reward processing in primate orbitofrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:272–284. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Doherty JP, Deichmann R, Critchley HD, Dolan RJ. Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. Neuron. 2002;33:815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin HH, Knowlton BJ, Balleine BW. Lesions of dorsolateral striatum preserve outcome expectancy but disrupt habit formation in instrumental learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:181–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends in neurosciences. 1989;12:366–375. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.Yin HH. The Basal Ganglia in Action. Neuroscientist. 2017;23 doi: 10.1177/1073858416654115. A review of the role of the basal ganglia circuits in movement, with emphasis on the relationship between velocity control and position control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu C, Gupta J, Chen JF, Yin HH. Genetic deletion of A2A adenosine receptors in the striatum selectively impairs habit formation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15100–15103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4215-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, He Y, Chen M, Pu Z, Chen L, Li P, Li B, Li H, Huang ZL, Li Z, et al. Optogenetic Activation of Adenosine A2A Receptor Signaling in the Dorsomedial Striatopallidal Neurons Suppresses Goal-Directed Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1003–1013. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furlong TM, Supit AS, Corbit LH, Killcross S, Balleine BW. Pulling habits out of rats: adenosine 2A receptor antagonism in dorsomedial striatum rescues methamphetamine-induced deficits in goal-directed action. Addict Biol. 2017;22:172–183. doi: 10.1111/adb.12316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ade KK, Wan Y, Chen M, Gloss B, Calakos N. An Improved BAC Transgenic Fluorescent Reporter Line for Sensitive and Specific Identification of Striatonigral Medium Spiny Neurons. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:32. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **29.O'Hare JK, Ade KK, Sukharnikova T, Van Hooser SD, Palmeri ML, Yin HH, Calakos N. Pathway-Specific Striatal Substrates for Habitual Behavior. Neuron. 2016;89:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.032. Shows that both direct and indirect pathway neurons increase response to input following habit formation. Relative timing of these two pathways is altered, with earlier activation of the direct pathway. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman J, Ressler RL, Packard MG. The dorsolateral striatum selectively mediates extinction of habit memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;136:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt R, Leventhal DK, Mallet N, Chen F, Berke JD. Canceling actions involves a race between basal ganglia pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1118–1124. doi: 10.1038/nn.3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallet N, Schmidt R, Leventhal D, Chen F, Amer N, Boraud T, Berke JD. Arkypallidal Cells Send a Stop Signal to Striatum. Neuron. 2016;89:308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo CC, Wang XJ. Cortico-basal ganglia circuit mechanism for a decision threshold in reaction time tasks. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:956–963. doi: 10.1038/nn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cui G, Jun SB, Jin X, Pham MD, Vogel SS, Lovinger DM, Costa RM. Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature. 2013;494:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klaus A, Martins GJ, Paixao VB, Zhou P, Paninski L, Costa RM. The Spatiotemporal Organization of the Striatum Encodes Action Space. Neuron. 2017;95:1171–1180. e1177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong Q, Znamenskiy P, Zador AM. Selective corticostriatal plasticity during acquisition of an auditory discrimination task. Nature. 2015;521:348–351. doi: 10.1038/nature14225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 37.O'Hare JK, Li H, Kim N, Gaidis E, Ade K, Beck J, Yin H, Calakos N. Striatal fast-spiking interneurons selectively modulate circuit output and are required for habitual behavior. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.26231. Provides the first evidence that FSIs are more excitable in habitual mice and that chemogenetic inhibition of FSIs in DLS prevents the expression of habitual lever pressing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tepper JM, Tecuapetla F, Koos T, Ibanez-Sandoval O. Heterogeneity and diversity of striatal GABAergic interneurons. Front Neuroanat. 2010;4:150. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramanathan S, Hanley JJ, Deniau JM, Bolam JP. Synaptic convergence of motor and somatosensory cortical afferents onto GABAergic interneurons in the rat striatum. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8158–8169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08158.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldridge JW, Berridge KC. Coding of serial order by neostriatal neurons: a"natural action" approach to movement sequence. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2777–2787. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02777.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin HH, Mulcare SP, Hilario MR, Clouse E, Holloway T, Davis MI, Hansson AC, Lovinger DM, Costa RM. Dynamic reorganization of striatal circuits during the acquisition and consolidation of a skill. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:333–341. doi: 10.1038/nn.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin HH. The sensorimotor striatum is necessary for serial order learning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:14719–14723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3989-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin HH. The role of the murine motor cortex in action duration and order. Front Integr Neurosci. 2009;3:23. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.023.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim N, Barter JW, Sukharnikova T, Yin HH. Striatal firing rate reflects head movement velocity. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40:3481–3490. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panigrahi B, Martin KA, Li Y, Graves AR, Vollmer A, Olson L, Mensh BD, Karpova AY, Dudman JT. Dopamine Is Required for the Neural Representation and Control of Movement Vigor. Cell. 2015;162:1418–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barter J, Li S, Lu D, Rossi M, Bartholomew R, Shoemaker CT, Salas-Meza D, Gaidis E, Yin HH. Beyond reward prediction errors: the role of dopamine in movement kinematics. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2015;9:39. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2015.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barter JW, Li S, Sukharnikova T, Rossi MA, Bartholomew RA, Yin HH. Basal ganglia outputs map instantaneous position coordinates during behavior. Journal of Neuroscience. 2015;35:2703–2716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3245-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin HH. Cortico-basal ganglia networks and the neural substrates of actions. In: Noronha A, editor. Neurobiology of Alcohol Dependence. Academic Press; 2014. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- * 49.Rueda-Orozco PE, Robbe D. The striatum multiplexes contextual and kinematic information to constrain motor habits execution. Nature neuroscience. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nn.3924. Shows that kinematic representations in the dorsolateral striatum can change with habit formation using locomotion as a behavioral measure. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shan Q, Ge M, Christie MJ, Balleine BW. The Acquisition of Goal-Directed Actions Generates Opposing Plasticity in Direct and Indirect Pathways in Dorsomedial Striatum. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:9196–9201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0313-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 51.Rothwell PE, Hayton SJ, Sun GL, Fuccillo MV, Lim BK, Malenka RC. Input- and Output-Specific Regulation of Serial Order Performance by Corticostriatal Circuits. Neuron. 2015;88:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.035. Shows that plasticity in the corticostriatal projections from the secondary motor cortex to the dorsolateral striatum is critical for learning of serial order (a simple AB sequence of nose pokes in mice) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 52.Murray JM, Escola GS. Learning multiple variable-speed sequences in striatum via cortical tutoring. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.26084. Presents a biologically plausible model of sequence learning and performance. Shows how the striatal recurrent inhibition network can acquire new sequences and scale the speed at which these sequences are performed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adermark L, Lovinger DM. Frequency-dependent inversion of net striatal output by endocannabinoid-dependent plasticity at different synaptic inputs. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1375–1380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3842-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bjursten L-M, Norrsell K, Norrsell U. Behavioural repertory of cats without cerebral cortex from infancy. Experimental brain research. 1976;25:115–130. doi: 10.1007/BF00234897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]