Abstract

Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) is characterized by compact and trabecular layers of the left ventricular myocardium. This cardiomyopathy may occur with congenital heart disease (CHD). Single cases document co-occurrence of LVNC and heterotaxy, but no data exist regarding the prevalence of this association. This study sought to determine whether a non-random association of LVNC and heterotaxy exists by evaluating the prevalence of LVNC in patients with heterotaxy.

In a retrospective review of the Indiana Network for Patient Care, we identified 172 patients with heterotaxy (69 male, 103 female). Echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging results were independently reviewed by two cardiologists to ensure reproducibility of LVNC. A total of 13/172 (7.5%) patients met imaging criteria for LVNC. The CHD identified in this subgroup included atrioventricular septal defects [11], dextrocardia [10], systemic and pulmonary venous return abnormalities [7], and transposition of the great arteries [5]. From this subgroup, 61% (n = 8) of the patients developed arrhythmias; and 61% (n = 8) required medical management for chronic heart failure.

This study indicates that LVNC has increased prevalence among patients with heterotaxy when compared to the general population (0.014–1.3%) suggesting possible common genetic mechanisms. Interestingly, mice with a loss of function of Scrib or Vangl2 genes showed abnormal compaction of the ventricles, anomalies in cardiac looping, and septation defects in previous studies. Recognition of the association between LVNC and heterotaxy is important for various reasons. First, the increased risk of arrhythmias demonstrated in our population. Secondly, theoretical risk of thromboembolic events remains in any LVNC population. Finally, many patients with heterotaxy undergo cardiac surgery (corrective and palliative) and when this is associated with LVNC, patients should be presumed to incur a higher peri-operative morbidity based on previous studies. Further research will continue to determine long-term and to corroborate genetic pathways.

Keywords: Left ventricular noncompaction, Cardiomyopathy, Heterotaxy syndrome, MHY7 variant

1. Introduction

Left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) is a clinically heterogeneous 1 currently classified as a primary genetic cardiomyopathy by the American Heart Association [1]. It is characterized by a two-layered structure consisting of prominent trabeculations and inter-trabecular recesses [2–4]. The mechanistic basis for this cardiomyopathy remains controversial but it is thought to be secondary to an early fetal arrest of myocardial development with lack of compaction of the myocardial meshwork [2,3,5–7]. Based on the morphologic appearance of the myocardium, diagnostic criteria have been generated from different imaging modalities [8–12]. The prevalence of LVNC is rather difficult to accurately obtain however some studies estimate it at about 0.014–1.3% in the general population [3,7,8,13–15]; however, this is probably an underestimate, since improved echocardiographic image quality and increasing awareness of LVNC has led to enhanced recognition. LVNC has been associated with different modes of inheritance including: X-linked, autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, mitochondrial [12,16]. This cardiomyopathy has also been associated with several genetic syndromes, inborn errors of metabolism, and mitochondrial disorders [1]. In addition, single genetic causes of LVNC have been associated to genes encoding sarcomeric and cytoskeletal proteins, and genes implicated in cardiac morphogenesis, such as DTNA, LDB3, MYH7, MYBPC3, ACTC1, NNT, among others [2,16–19]. Corroboration of LVNC in association with various forms of congenital heart disease (CHD) has been documented; some of these forms include but are not limited to stenotic lesions of the left ventricular outflow tract, Ebstein's anomaly, septation defects and tetralogy of Fallot [7,20,21].

Heterotaxy is a heterogeneous syndrome where the internal thoraco-abdominal organs demonstrate abnormal arrangement across the left-right axis of the body [20]. Cardiovascular malformations are commonly encountered in this condition due to abnormal heart looping during development [22,23]. The prevalence of heterotaxy in the general population has been reported as approximately 1 in 10,000 individuals [24]. Heterotaxy has the highest relative recurrence risk among congenital heart defects, indicating a strong genetic basis [18,20]. Mutations in ZIC3 cause the X-linked form of heterotaxy [18,25–28]. In addition, mutations in genes important for cilia function underlie a subset of heterotaxy cases, often autosomal recessive in nature and overlapping with primary ciliary dyskinesia [29,30]. However, despite a good understanding of left-right development from animal models, in the majority of patients a genetic cause for heterotaxy is not well established [17,31,32]. From the clinical perspective, heterotaxy syndrome has been associated with increased postoperative mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing cardiac surgical procedures [20,24,29,33]. Single cases have documented co-occurrence of LVNC and heterotaxy syndrome, but no data exist on the prevalence of this association [34]. In this study, we sought to determine whether a nonrandom association of LVNC and heterotaxy exists by evaluating the prevalence of LVNC in patients with heterotaxy and CHD.

2. Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Indiana University Health approved the project. For the purposes of this study, we performed a retrospective chart review of medical records to identify patients with situs abnormalities. This information was obtained from the Indiana Network for Patient Care. By reviewing medical records, a total of 172 individuals were identified with heterotaxy syndrome and concomitant congenital heart disease (69 male, 103 female). Echocardiography was obtained in all patients, additional cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) was available in three patients who did not have good quality echocardiograms due to poor imaging windows; all the studies (at least three different echocardiograms per patient) were independently reviewed by two cardiologists with additional expertise in heart failure and cardiomyopathies to ensure reproducibility in the diagnosis of LVNC. The echocardiographic criteria for LVNC was defined as the presence of a two-layered myocardial structure (a compact epicardial layer and an endocardial layer consisting of a prominent trabecular meshwork and deep intertrabecular spaces) particularly towards the apex at the end of systole in a standard parasternal short axis view. A non-compacted to a compacted layer ratio > 2:1 was determined to be diagnostic based on previous publications [8,35]. Patients who met this criterion also presented multiple recesses in the left ventricular walls that communicate with the ventricular cavity by 2D and color Doppler echocardiography. Diagnosis for LVNC by cMRI was based on long axis views at the end of diastole in which the non-compacted to compacted ratio measured > 2.3:1 at the end of diastole [9]. Electrocardiograms, 24-hour Holter monitoring and telemetry reports were assessed to determine the prevalence and type of rhythm abnormalities. Heterotaxy was diagnosed when patients with congenital heart defect(s) had at least one additional visceral situs anomaly or evidence of isomerism.

3. Results

We identified 172 patients with heterotaxy syndrome associated with congenital heart disease. After completing the evaluation of cardiac imaging in this cohort, we found thirteen patients (7.5%) who met non-invasive imaging criteria for LVNC (three patients were diagnosed by cMRI and ten of them by echocardiography). From these thirteen patients, only one had been previously identified to have LVNC, demonstrating that it was under-recognized initially. Demographics of this subgroup showed 70% White (n = 9), 15% Asian (n = 2), 15% African American (n = 2). Cardiovascular malformations identified in the LVNC patients included but were not limited to atrioventricular septal defects [11], dextrocardia [10], systemic and pulmonary venous drainage abnormalities [7], and transposition of the great arteries [5]. All the patients in this subgroup underwent surgical procedures to repair or palliate their congenital heart defects; a summary of the cardiac defects is presented on Table 1. Most patient were able to undergo surgical repair with biventricular physiology (n = 7) 54%; some were palliated for the single ventricle anatomy (n = 6) 38%; and (n = 1) 8% died in the neonatal period with no opportunity to undergo any surgical intervention except for a pacemaker implantation. At birth, this patient presented with prominent noncompaction cardiomyopathy which manifested soon a full spectrum of comorbidities; including severe cardiac dysfunction, thromboembolic events and supraventricular tachycardia (Fig. 1). From the electrophysiologic stand point, 61% (n = 8) had abnormalities, including supraventricular tachyarrhythmias (n = 5), congenital atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker implantation (n = 2), and post-surgical atrioventricular block (n = 1); these findings are summarized in Table 1. From the group of patients presenting with heterotaxy and LVNC, subjects 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13 (61%) have required long-term (> 6 months) medical therapy for myocardial dysfunction after their latest surgical or palliative procedure (Table 1). The presence of arterial and venous thromboembolic events was reviewed; when present, some these cases were related to the use of central venous catheters hence further statistical analyses were not performed.

Table 1.

Summary of cardiovascular phenotype of the heterotaxy/LVNC group.

| Subjects | CHD diagnosis | Initial surgical procedure | Genetics analysis | Current CV medical therapy | EP disturbances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject 1 | Dex, AVSD, DORV, L-TGA, PS | Modified BTS and PDA ligation. | n/a | Captopril, Atenolol, Digoxin, Sildenafil, Aspirin | Postoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia |

| Subject 2 | Dex, AVSD, PAPVR, iIVC with Azy cont, LSVC | AV canal repair | 1.17-megabase duplication at 13q31.1 identified by CGH. | None | Atrial ectopic tachycardia, complete AV block |

| Subject 3 | Dex, uAVSD, AS, PAPVR, LSVC | DKS + modified BTS | n/a | Aspirin | Complete AV block |

| Subject 4 | Levocardia, uAVSD, TAPVR, iIVC with Azy cont | AV canal repair | n/a | None | Atrial ectopic tachycardia |

| Subject 5 | Levocardia, AVSD, CoA, iIVC with Azy cont | CoA repair | 1.19-megabase deletion at 1q21.1 identified by CGH. | None | Postoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia |

| Subject 6 | Levocardia, uAVSD, iIVC with Azy cont, LSVC, PAPVR | uAVSD | 596.05-kb deletion at 3q25 identified by CGH. | Losartan | None |

| Subject 7 | Dex, L-TGA, VSD, PS | None | n/a | None | None |

| Subject 8 | Dex, L-TGA, ASD, VSD, PS, PAPVR | Double switch, PAPVR repair | n/a | Digoxin, Metoprolol | Atrial flutter |

| Subject 9 | Dex, uAVSD | Glenn procedure | n/a | Carvedilol | Atrial ectopic tachycardia |

| Subject 10 | Dex, uAVSD, iIVC with Azy cont | AV canal repair | n/a | Carvedilol | None |

| Subject 11 | Dex, AVSD, DORV, LSVC, TAPVR | Pacemaker implantation | Normal CMA, 4 VUS from the heterotaxy gene panel by GeneDx® | Milrinone | Congenital compete AV block |

| Subject 12 | Dex, L-TGA, PS, uAVC, Ebstein's anomaly | Modified BTS | Normal 22q FISH analysis | Aspirin, Captopril, Coumadin, Furosemide | None |

| Subject 13 | Dex, D-TGA, PS, uAVSD | DKS + modified BTS | n/a | Digoxin, Lisinopril | None |

This table is assorted by subject number and it describes the cardiac phenotype in these patients, their initial surgical procedure, the post-operative medical regimen, and their genetic analysis when available.

(AS) aortic valve stenosis; (ASD) atrial septal defect; (AV) atrioventricular; (AVSD) atrioventricular septal defect; (Azy cont) azygous vein continuation to the superior vena cava; (BTS) Blalock-Taussig shunt; (CGH) comparative genomic hybridization; (CMA) chromosomal microarray; (CoA) coarctation of the aorta; (CTJ) cervicothoracic junction; (CV) cardiovascular; (DD) developmental delay; (Dex) dextrocardia; (DKS) Damus-Kaye-Stansel procedure; (DORV) double outlet right ventricle; (D-TGA) D-transposition of the great arteries; (EP) electrophysiological; (FISH) fluorescent in situ hybridization; (iIVC) interrupted inferior vena cava; (LSVC) left superior vena cava; (L-TGA) L-transposition of the great arteries; (PAPVR) partial anomalous pulmonary venous return; (PDA) patent ductus arteriosus; (PS) pulmonary valve stenosis; (TAPVR) total anomalous pulmonary venous return; (uAVSD) unbalanced atrioventricular septal defect; (VSD) ventricular septal defect; (VUS) variant of unknown significance.

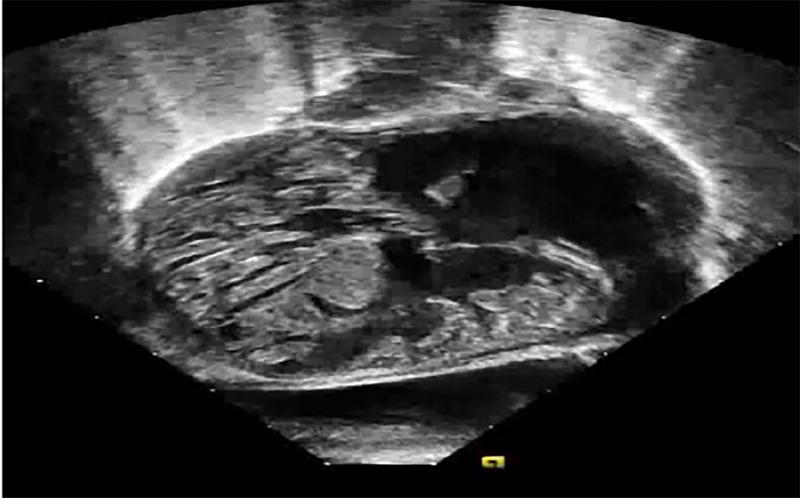

Fig. 1.

Echocardiographic imaging of LVNC in the setting of heterotaxy syndrome. Echocardiography shows from a subcostal 4-chamber view, a patient with dextroversion, an unbalanced atrioventricular septal defect, and LVNC characterized by a prominent myocardial trabeculations and deep intertrabecular recesses.

4. Discussion

This study reveals that LVNC has an increased prevalence among patients with heterotaxy (7.5%) when compared to the general population (0.014–1.3%) [3,7,8,13–15]. In this retrospective review, we observed that patients with bilateral right-sidedness presented a more complex cardiovascular phenotype, Table 1. In fact, the only patient who died at a young age within this cohort, belonged to this subtype and passed away at age three weeks. Knowledge of the association of heterotaxy and LVNC is important for the awareness of clinical implications in the pre- and post-operative periods which may identify a population at increased risk for additional morbidity [20,21]. Although the percentage of patients requiring heart failure therapy is elevated in this group (n = 8; 61%), one may opine that the clinical interpretation is variable due to the difference in the anatomy of these patients, and the surgical techniques used to manage them. After data collection was extracted, we attempted to analyze patient re-hospitalization rate, length of stay, and thromboembolic episodes as specific predictors of morbidity and mortality in this population. The attempt to analyze these data was not feasible due to a small number of subjects in the cohort, the lack of a control group and unmeasured factors that differed between these patients. This study is also limited by collection of data from a single institution. Some frequent postoperative comorbidities linked to heterotaxy syndrome include arrhythmias, prolonged pleural effusions and re-operation [22,36,37]. Although LVNC and heterotaxy are recognized as disorders with a genetic etiology based on the heritability of their manifestations, potential genetic pathways responsible for their co-occurrence have not been investigated. Interestingly, mice with a loss of function of Scrib or Vangl2 genes show abnormal compaction of the ventricular walls, anomalies in cardiac looping and septation defects [17,31]. The Drosophila scribble gene regulates apical-basal polarity and is implicated in control of cellular architecture and cell growth control; mutations in mammalian Scrib (circletail; Crc mutant) also result in neural tube defects and body axis anomalies similar to those observed when the planar cell polarity (PCP) gene Vangl2 is disrupted in the loop-tail (Lp) mutant models; further studies have concluded that Scrib and Vangl2 are not only required for PCP signaling during early embryogenesis but also for cardiomyocyte organization in the primary heart tube [31,38,39]. The phenotype of these mice suggest that shared characteristics of a primitive myocardium and abnormal cellular polarity in these disorders may encompass common developmental and genetic mechanisms [31]. Loss of Scrib prevents normal heart looping resulting in a clearly abnormal cardiac anatomy such as discordant ventriculo-arterial connections, double outlet right ventricle, atrioventricular septal defects and abnormal asymmetrical remodeling of the aortic arch arteries [31]. Interestingly, a study from Phillips et al. also demonstrated that the ventricles in Crc/Crc mutants remained with prominent trabeculae with deep intratrabecular recesses extending to the subepicardial region when compared with developmentally matched control embryos [31]. These abnormalities in the organization of the ventricular myocardium are similar to those described in the human cardiomyopathy, LVNC [35].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study indicates that LVNC has an increased prevalence among patients with heterotaxy when compared to the general population suggesting possible common developmental and genetic mechanisms. Recognition of this association between LVNC and heterotaxy syndrome is important for clinicians for multiple reasons. First, the increased risk of arrhythmias demonstrated in our population. Secondly, theoretical risk of thromboembolic events remains in any LVNC population. Finally, many patients with heterotaxy undergo cardiac surgery (corrective and palliative) and when this is also associated with LVNC these patients should be presumed to incur a higher peri-operative morbidity based on previous studies. Further research will continue to determine long-term outcome in this population and possibly to corroborate common genetic pathways.

Acknowledgments

Lindsey R. Elmore, clinical research coordinator.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, et al. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2006;113:1807–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. (published online EpubApr 11) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finsterer J, Stollberger C, Towbin JA. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy: cardiac, neuromuscular, and genetic factors. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.207. (published online EpubJan 12) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Andre F, Burger A, Lossnitzer D, Buss SJ, Abdel-Aty H, Gianntisis E, et al. Reference values for left and right ventricular trabeculation and non-compacted myocardium. Int J Cardiol. 2015;185:240–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.065. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.065. (published online EpubApr 15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tizon-Marcos H, de la Paz Ricapito M, Pibarot P, Bertrand O, Bibeau K, Le Ven F, et al. Characteristics of trabeculated myocardium burden in young and apparently healthy adults. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1094–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.025. (published online EpubOct 01) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussein A, Karimianpour A, Collier P, Krasuski RA. Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricle in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:578–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.017. (published online EpubAug 04) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W, Chen H, Qu X, Chang CP, Shou W. Molecular mechanism of ventricular trabeculation/compaction and the pathogenesis of the left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) Am J Med Genet C: Semin Med Genet. 2013;163C:144–56. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31369. (published online EpubAug) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stahli BE, Gebhard C, Biaggi P, Klaassen S, Valsangiacomo Buechel E, Attenhofer Jost CH, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: prevalence in congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2477–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.095. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.095. (published online EpubSep 10) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oechslin E, Jenni R. Left ventricular non-compaction revisited: a distinct phenotype with genetic heterogeneity? Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1446–56. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq508. (published online EpubJun) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen SE, Selvanayagam JB, Wiesmann F, Robson MD, Francis JM, Anderson RH, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction: insights from cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:101–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.045. (published online EpubJul 05) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bax JJ, Lamb HJ, Poldermans D, Schalij MJ, de Roos A, van der Wall EE. Noncompaction cardiomyopathy-echocardiographic diagnosis. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2002;3:301–2. (published online EpubDec) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreini D, Pontone G, Bogaert J, Roghi A, Barison A, Schwitter J, et al. Long-term prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance in left ventricle noncompaction: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2166–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.053. (published online EpubNov 15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arbustini E, Favalli V, Narula N, Serio A, Grasso M. Left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct genetic cardiomyopathy? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:949–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.096. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.096. (published online EpubAug 30) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pignatelli RH, McMahon CJ, Dreyer WJ, Denfield SW, Price J, Belmont JW, et al. Clinical characterization of left ventricular noncompaction in children: a relatively common form of cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;108:2672–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100664.10777.B8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000100664.10777.B8. (published online EpubNov 25) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aras D, Tufekcioglu O, Ergun K, Ozeke O, Yildiz A, Topaloglu S, et al. Clinical features of isolated ventricular noncompaction in adults long-term clinical course, echocardiographic properties, and predictors of left ventricular failure. J Card Fail. 2006;12:726–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.08.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.08.002. (published online EpubDec) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanton C, Bruce C, Connolly H, Brady P, Syed I, Hodge D, et al. Isolated left ventricular noncompaction syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1135–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.062. (published online EpubOct 15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tariq M, Ware SM. Importance of genetic evaluation and testing in pediatric cardiomyopathy. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:1156–65. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i11.1156. http://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i11.1156. (published online EpubNov 26) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boczonadi V, Gillespie R, Keenan I, Ramsbottom SA, Donald-Wilson C, Al Nazer M, et al. Scrib: Rac1 interactions are required for the morphogenesis of the ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104:103–15. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvu193. (published online EpubOct 01) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware SM, Peng J, Zhu L, Fernbach S, Colicos S, Casey B, et al. Identification and functional analysis of ZIC3 mutations in heterotaxy and related congenital heart defects. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:93–105. doi: 10.1086/380998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/380998. (published online EpubJan) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bainbridge MN, Davis EE, Choi WY, Dickson A, Martinez HR, Wang M, et al. Loss of function mutations in NNT are associated with left ventricular noncompaction. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:544–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/circgenetics.115.001026. (published online EpubAug) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs JP, Pasquali SK, Morales DL, Jacobs ML, Mavroudis C, Chai PJ, et al. Heterotaxy: lessons learned about patterns of practice and outcomes from the congenital heart surgery database of the society of thoracic surgeons. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2011;2:278–86. doi: 10.1177/2150135110397670. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2150135110397670. (published online EpubApr) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran P, Woo JG, Ryan TD, Bryant R, Heydarian HC, Jefferies JL, et al. The impact of concomitant left ventricular non-compaction with congenital heart disease on perioperative outcomes. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37:1307–12. doi: 10.1007/s00246-016-1435-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00246-016-1435-2. (published online EpubOct) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGovern E, Kelleher E, Potts JE, O'Brien J, Walsh K, Nolke L, et al. Predictors of poor outcome among children with heterotaxy syndrome: a retrospective review. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000328. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2015-000328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedom RM, Jaeggi ET, Lim JS, Anderson RH. Hearts with isomerism of the right atrial appendages - one of the worst forms of disease in 2005. Cardiol Young. 2005;15:554–67. doi: 10.1017/S1047951105001708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1047951105001708. (published online EpubDec) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin AE, Ticho BS, Houde K, Westgate MN, Holmes LB. Heterotaxy: associated conditions and hospital-based prevalence in newborns. Genet Med. 2000;2:157–72. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200005000-00002. (10.109700125817-200005000-00002 published online EpubMay–Jun) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebbia M, Towbin JA, Casey B. Failure to detect connexin43 mutations in 38 cases of sporadic and familial heterotaxy. Circulation. 1996;94:1909–12. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belmont JW, Mohapatra B, Towbin JA, Ware SM. Molecular genetics of heterotaxy syndromes. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:216–20. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cowan J, Tariq M, Ware SM. Genetic and functional analyses of ZIC3 variants in congenital heart disease. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:66–75. doi: 10.1002/humu.22457. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/humu.22457. (published online EpubJan) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowan JR, Tariq M, Shaw C, Rao M, Belmont JW, Lalani SR, et al. Copy number variation as a genetic basis for heterotaxy and heterotaxy-spectrum congenital heart defects. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2016;371 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0406. (published online EpubDec 19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW, Dell S, Morgan L, Molina PL, et al. Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation. 2007;115:2814–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649038. (published online EpubJun 05) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapiro AJ, Davis SD, Ferkol T, Dell SD, Rosenfeld M, Olivier KN, et al. Laterality defects other than situs inversus totalis in primary ciliary dyskinesia: insights into situs ambiguus and heterotaxy. Chest. 2014;146:1176–86. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1704. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1704. (published online EpubNov) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips HM, Rhee HJ, Murdoch JN, Hildreth V, Peat JD, Anderson RH, et al. Disruption of planar cell polarity signaling results in congenital heart defects and cardiomyopathy attributable to early cardiomyocyte disorganization. Circ Res. 2007;101:137–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.142406. (published online EpubJul 20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware SM, Harutyunyan KG, Belmont JW. Heart defects in X-linked heterotaxy: evidence for a genetic interaction of Zic3 with the nodal signaling pathway. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1631–7. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.20719. (published online EpubJun) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutherland MJ, Ware SM. Disorders of left-right asymmetry: heterotaxy and situs inversus. Am J Med Genet C: Semin Med Genet. 2009;151C:307–17. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.30228. (published online EpubNov 15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goncalves LF, Souto FM, Faro FN, Mendonca Rde C, Oliveira JL, Sousa AC. Dextrocardia with situs inversus associated with non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;101:e33–6. doi: 10.5935/abc.20130158. http://dx.doi.org/10.5935/abc.20130158. (published online EpubAug) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenni R, Oechslin E, Schneider J, Attenhofer Jost C, Kaufmann PA. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: a step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2001;86:666–71. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azakie A, Merklinger SL, Williams WG, Van Arsdell GS, Coles JG, Adatia I. Improving outcomes of the Fontan operation in children with atrial isomerism and heterotaxy syndromes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1636–40. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim HG, Bacha EA, Marx GR, Marshall A, Fynn-Thompson F, Mayer JE, et al. Biventricular repair in patients with heterotaxy syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:371–9. e373. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.027. (published online EpubFeb) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murdoch JN, Rachel RA, Shah S, Beermann F, Stanier P, Mason CA, et al. Circletail, a new mouse mutant with severe neural tube defects: chromosomal localization and interaction with the loop-tail mutation. Genomics. 2001;78:55–63. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/geno.2001.6638. (published online EpubNov) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montcouquiol M, Rachel RA, Lanford PJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kelley MW. Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature. 2003;423:173–7. doi: 10.1038/nature01618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature01618. (published online EpubMay 08) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]