Abstract

Aims

Explore the association between clinical findings and prognosis in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) and analyze the influence of etiology on clinical presentation and prognosis.

Methods and results

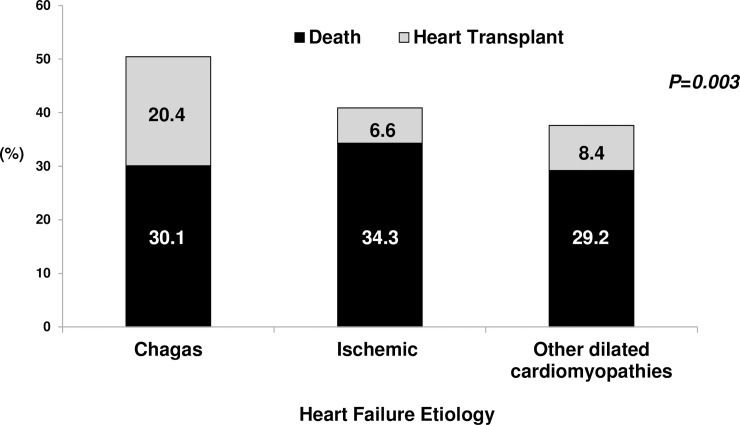

Prospective cohort of 500 patients admitted with ADHF from Aug/2013-Feb/2016; patients were predominantly male (61.8%), median age was 58 (IQ25-75% 47–66 years); etiology was dilated cardiomyopathy in 141 (28.2%), ischemic heart disease in 137 (27.4%), and Chagas heart disease in 113 (22.6%). Patients who died (154 [30.8%]) or underwent heart transplantation (53[10.6%]) were younger (56 years [IQ25-75% 45–64 vs 60 years, IQ25-75% 49–67], P = 0.032), more frequently admitted for cardiogenic shock (20.3% vs 6.8%, P<0.001), had longer duration of symptoms (14 days [IQ25-75% 4–32.8 vs 7.5 days, IQ25-75% 2–31], P = 0.004), had signs of congestion (90.8% vs 76.5%, P<0.001) and inadequate perfusion more frequently (45.9% vs 28%, P<0.001), and had lower blood pressure (90 [IQ25-75% 80–100 vs 100, IQ25-75% 90–120], P<0.001). In a logistic regression model analysis, systolic blood pressure (P<0.001, OR 0.97 [95%CI 0.96–0.98] per mmHg) and jugular distention (P = 0.004, OR 1.923 [95%CI 1.232–3.001]) were significant. Chagas patients were more frequently admitted for cardiogenic shock (15%) and syncope/arrhythmia (20.4%). Pulmonary congestion was rare among Chagas patients and blood pressure was lower. The rate of in-hospital death or heart transplant was higher among patients with Chagas (50.5%).

Conclusions

A physical exam may identify patients at higher risk in a contemporaneous population. Our findings support specific therapies targeted at Chagas patients in the setting of ADHF.

Author summary

It is recognized that the clinical evaluation of patients remains the basis for the characterization of diseases, data interpretation, and patient care. However, incorporation of technological methods into clinical practice has challenged the way cardiologists’ value of history and clinical examination. The present study sought to analyze the importance of clinical findings in a contemporaneous cohort of patients admitted with decompensated heart failure. Our results indicate that the physical exam may identify patients at higher risk in a contemporaneous patient population, and that clinical presentation varies according to etiology—especially Chagas disease—and ventricular function. Our findings support the need of development of specific therapeutic approaches targeted at Chagas patients in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure, as they represent a more vulnerable population.

Introduction

Advances in technologies applied to medical diagnosis have broadened medical understanding of patients and opened new possibilities for therapeutic interventions; however, it is recognized that the clinical evaluation of patients remains the basis for the characterization of diseases, data interpretation, and patient care.[1] Despite the value of clinical history to medical practice, incorporation of technological methods has challenged the way cardiologists’ value history and clinical examination.[2] Additionally, there has been concern regarding the possibility that clinical skills may be lost in face of the extensive technological evaluation currently available.[3]

This is particularly the case with heart failure,[4] a clinical syndrome that results from different processes affecting the cardiovascular system. As a heterogeneous entity,[5] various forms of categorization have been proposed to describe manifestations, predict prognosis, and identify patient groups that may benefit from specific interventions.[6] Most of the data used to elaborate such categorizations is obtained through history and clinical examination. In acute decompensated heart failure patients, assessment of prognosis in individual patients has been especially challenging due to the variability in the clinical course and presentation of the disease, along with the presence of different etiologies. Even though some findings, such as the presence of a third heart sound[7] and persistent congestion,[8] have been associated with a worse prognosis, detailed clinical features, and their associations with prognosis and therapy have not been fully evaluated during episodes of acute decompensation in recent series that included a broad spectrum of etiologies.[9,10,11,12]

This is particularly the case of Chagas cardiomyopathy, an etiology consistently associated with worse prognosis in the setting of chronic heart failure.[13] Interest in Chagas disease has grown not only due to its epidemiologic importance in both endemic and non-endemic areas,[14] but also due to the possibility of a specific pattern of treatment response.[15] Despite the availability of a large amount of data regarding the clinical presentation and prognosis of ambulatory patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy, information regarding its importance during episodes of acute decompensated heart failure is scarce.

In the present study, we hypothesized that clinical findings of patients with acute decompensated heart failure may vary according to the heart failure etiology and left ventricular function, and may contribute to the prognostic evaluation in a contemporaneous cohort of patients.

Methods

Ethics statements

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research Project Analysis, which considered unfeasible and unnecessary to obtain formal consent from the patients studied.

Objective

The aim of our study was to analyze the association between findings from history and physical exam with in-hospital prognosis in patients with acute decompensated heart failure, and analyze the influence of Chagas etiology and left ventricular function on patient presentation and prognosis.

Study design

This was a prospective cohort study of patients admitted to the Heart Institute (InCor) of the Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (HC-FMUSP) with a diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure. The first inclusion occurred in August 2013 and the last inclusion in February 2016. Patients were followed until hospital discharge and all patient data analyzed were anonymized.

Patients

We included patients over 18 years of age admitted with a diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure, irrespective of the ejection fraction. We excluded patients hospitalized for less than 24 hours and patients with cardiogenic shock or decompensated heart failure during the postoperative period after heart surgery.

Variables

The data were obtained from medical records, including demographic information, epidemiological data, pathological history, reason for hospitalization, presence and duration of heart failure-related symptoms, etiologic diagnosis of heart failure or cardiomyopathy, physical examination data, electrocardiographic data, echocardiographic data, and major events during hospitalization, ie, death and heart transplantation.

Definitions

The diagnosis of heart failure was made according to the Framingham criteria.[16] Acute heart failure was defined as new-onset decompensated heart failure or exacerbation of chronic heart failure that met the above criteria and required unplanned hospitalization.

The diagnosis of heart failure etiology was based on (1) typical clinical presentation for a given etiology; (2) presence of confirmatory tests, as indicated; (3) exclusion of other possible etiologies. The diagnosis of ischemic etiology was based on the presence of a history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, previous coronary artery bypass surgery, stable angina pectoris with electrocardiographic changes, myocardial ischemia demonstrated by modified ergometric testing, and myocardial perfusion scintigraphy or coronary angiography showing ≥ 75% obstructions. The diagnosis of a Chagas etiology was based on positive serology for Chagas disease. The diagnosis of valvar etiology was based on a history of rheumatic heart disease or previous valve replacement surgery. The diagnosis of a hypertensive etiology was based on a history of severe hypertension and previous treatment with antihypertensive drugs, or evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram or echocardiogram in association with dilatation of the ventricular chambers.[17] The diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy was based on evidence of ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction by the different causes mentioned above. For the purpose of the present analysis, heart failure etiology was categorized in three groups: patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy, ischemic cardiomyopathy and those with dilated cardiomyopathy related to other conditions.

Patients were categorized according to the presence of symptoms and signs associated with congestion and/or inadequate perfusion. We considered as signs of congestion a history of orthopnea, jugular venous distention, rales, hepatojugular reflux, ascites, peripheral edema, and hepatomegaly; we considered symptomatic hypotension, cool extremities, impaired mentation, and oliguria to be signs of inadequate perfusion.

Patients were categorized according to hemodynamic profile at hospital admission. [18] We included in profile A, patients with no evidence of congestion or hypoperfusion; in profile B, patients with signs of congestion but adequate perfusion; in profile C, patients with signs of congestion and hypoperfusion; and profile L, patients with hypoperfusion but no signs of congestion. Patients were further categorized according to left ventricular ejection fraction measured by transthoracic echocardiography.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are described as absolute value and percentage; continuous variables are described as median ± interquartile range 25–75%. For non-normal distribution of variables, the nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used, and for the normal distribution, the Student paired t test was used. Comparison of proportions between groups was performed with the X2 test. Multivariate analysis was performed with stepwise logistic regression. We included in the model variables with a P value in univariate analysis less than 0.1. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 11.0.

Results

The study population consisted of 500 patients admitted with heart failure between August 2013 and February 2016 (Table 1); patients were predominantly male (61.8%), with a median age of 58 years (interquartile range [IQ] 47–66 years); main etiologies were dilated cardiomyopathy in 141(28.2%) patients, ischemic heart disease in 137 (27.4%), and Chagas heart disease in 113 (22.6%). The leading admission diagnoses were progressive heart failure (60.6%) and cardiogenic shock (12.4%); median left ventricular ejection fraction was 26% (IQ25-75% 22–35); median creatinine at admission was 1.65 mg/dL (IQ25-75% 1.23–2.34); and median brain natriuretic peptide was 1,086 pg/dL (IQ25-75% 463–2,028). During hospital admission, 154 (30.8%) patients died and 53 (10.6%) underwent heart transplantation.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients.

| Clinical characteristics | N(%)/median(IQR25-75) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 500 |

| Age (years) | 58 (47–66) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 309 (61.8) |

| Female | 191 (38.2) |

| Heart failure etiology | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 141 (28.2) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 137 (27.4) |

| Chagas heart disease | 113 (22.6) |

| Hypertension | 56 (11.2) |

| Valvular heart disease | 28 (5.6) |

| Others | 25 (5.0) |

| Admission diagnosis | |

| Progressive heart failure | 303 (60.6) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 62 (12.4) |

| Arrhythmia/Syncope | 53 (10.6) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 22 (4.4) |

| Infections | 15 (3.0) |

| Others | 45 (9.0) |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 10 (3–31) |

| Previous history | |

| Arterial hypertension | 262 (52.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 179 (35.8) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 156 (31.2) |

| Previous VT/VF | 68 (13.6) |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 26 (22–35) |

| Medications | |

| Beta-blocker | 397 (79.4) |

| ACE inhibitor/AT blocker | 312 (62.4) |

| Spironolactone | 269 (53.8) |

| Diuretics | 377 (75.4) |

| Digoxin | 115 (23) |

| Ivabradine | 8 (1.6) |

| Warfarin | 135 (27) |

| Inotropes | 148 (29.6) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.65 (1.23–2.34) |

| Brain natriuretic peptide (pg/dL) | 1086 (463–2028) |

| Implantable defibrillator | 59 (11.8) |

LV: left ventricle; VT: ventricular tachycardia; VF: ventricular fibrillation; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme

When clinical characteristics of patients were analyzed according to outcomes (Table 2), we found that, compared with patients discharged, patients who died or had a heart transplant during hospital stay were younger (median age 56 years [IQ25-75% 45–64 versus 60 years, IQ25-75% 49–67], respectively, P = 0.032), were more frequently admitted for cardiogenic shock (20.3% versus 6.8%, respectively, P<0.001), were less frequently admitted for arrhythmia or syncope (6.3% versus 13.7%, respectively, P<0.001), less frequently had a history of hypertension (45.9% versus 57%, respectively, P<0.018), had a longer duration of symptoms (14 days [IQ25-75% 4–32.8 versus 7.5 days, IQ25-75% 2–31], respectively, P = 0.004), more frequently had signs of congestion (90.8% versus 76.5%, respectively, P<0.001) and inadequate perfusion (45.9% versus 28%, respectively, P<0.001), and had lower blood pressure (90 [IQ25-75% 80–100 versus 100, IQ25-75% 90–120], respectively, P<0.001). These findings indicate the relevance of the admission diagnosis for the prognosis. Interestingly, we found no significant influence of gender, co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus and atrial fibrillation in prognosis.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of patients according to outcomes.

| Clinical characteristics | Discharge% N(%)/median(IQR25-75) |

Death/Transplant N(%)/median(IQR25-75) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 293 | 207 | |

| Age (years) | 60 (49–67) | 56 (45–64) | 0.032 |

| Sex | 0.64 | ||

| Male | 184 (62.8) | 125 (60.4) | |

| Female | 109 (37.2) | 82 (39.6) | |

| Admission diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| Progressive heart failure | 178 (60.8) | 125 (60.4) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 20 (6.8) | 42 (20.3) | |

| Arrhythmia/Syncope | 40 (13.7) | 13 (6.3) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 14 (4.8) | 8 (3.9) | |

| Infections | 8 (2.7) | 7 (3.4) | |

| Others | 33 (11.3) | 12 (5.8) | |

| Heart failure etiology | 0.072 | ||

| Chagas Heart Disease | 56 (19.1) | 57 (27.5) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 81 (27.6) | 56 (27.1) | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 156 (53.2) | 94 (45.4) | |

| Previous history | |||

| Hypertension | 167 (57) | 95 (45.9) | 0.018 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 88 (30) | 68 (32.9) | 0.557 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 102 (34.8) | 77 (37.2) | 0.636 |

| Symptoms at admission | |||

| Orthopnea | 134 (45.7) | 109 (52.7) | 0.146 |

| NPD | 121 (41.3) | 99 (47.8) | 0.17 |

| Chest pain | 91 (31.1) | 52 (25.1) | 0.16 |

| Syncope | 38 (3) | 36 (17.4) | 0.201 |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 7.5 (2–31) | 14 (4–32.8) | 0.004 |

| Physical exam | |||

| Any sign of congestion | 224 (76.5) | 188 (90.8) | <0.001 |

| Lower limbs edema | 146 (49.8) | 127 (61.4) | 0.014 |

| Pulmonary rales | 131 (44.7) | 99 (47.8) | 0.524 |

| Jugular distension | 127 (43.3) | 136 (65.7) | <0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 99 (33.8) | 98 (47.3) | 0.003 |

| Ascites | 50 (17.1) | 60 (29) | 0.002 |

| Mitral systolic murmur | 74 (25.3) | 78 (37.7) | 0.003 |

| Tricuspid systolic murmur | 25 (8.5) | 20 (9.7) | 0.751 |

| Third heart sound | 21 (7.2) | 9 (4.3) | 0.251 |

| Inadequate perfusion | 88 (28) | 95 (45.9) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 80 (68–100.5) | 80 (68–96) | 0.419 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 100 (90–120) | 90 (80–100) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 70 (60–80) | 60 (56–70) | <0.001 |

bpm: beats per minute; BP: blood pressure; mm Hg: millimeters of mercury; NPD: nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnea

When these variables were analyzed in a logistic regression model, only systolic blood pressure (P<0.001, OR 0.97 [95% CI 0.96–0.98] per mmHg) and jugular distention (P = 0.004, OR 1.923 [95% CI 1.232–3.001]) remained as statistically significant variables (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable analysis of clinical findings associated with the occurrence of death or heart transplantation during hospital admission.

| Variable | P | OR | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.479 | 0.995 | 0.982–1.008 |

| Lower limb edema | 0.086 | 1.461 | 0.948–2.251 |

| Jugular distension | 0.004 | 1.923 | 1.232–3.001 |

| Ascites | 0.582 | 1.156 | 0.691–1.934 |

| Hepatomegaly | 0.626 | 0.894 | 0.571–1.401 |

| Inadequate perfusion | 0.226 | 1.296 | 0.852–1.973 |

| Systolic mitral murmur | 0.186 | 1.336 | 0.870–2.051 |

| Systolic blood pressure | <0.001 | 0.970 | 0.960–0.980 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Analysis according to etiology

When patients were analyzed according to etiology (Table 4), we found that their clinical characteristics differed regarding age, sex distribution, admission diagnosis, duration of symptoms, and findings on physical exam. Patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy were younger than patients with ischemic heart disease (median 56 years [IQ25-75 45–63]; 53.5 [41–64]; 63 [57–71], respectively; P<0.001) and had lower proportion of male patients (55.8%; 53.5% and 72.3% respectively, P = 0.01). Chagas patients were more frequently admitted for cardiogenic shock than patients with ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy (15%; 11.7%; 11.6%, respectively; P<0.001). Furthermore, admission for syncope or arrhythmia was most frequent among Chagas patients (20.4%). Regarding findings on the physical exam, signs of pulmonary congestion were less frequently found among Chagas patients (pulmonary rales in 29.2%) compared with other etiologies. Admission blood pressure, however, was lowest among Chagas patients (systolic blood pressure 90 mm Hg [IQ25-75 80–100]; diastolic blood pressure 61 mm Hg [IQ25-75 55–72]). The distribution of in-hospital outcomes according to etiology showed that patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy had the highest rate of death or heart transplant (50.5%)(Fig 1); it is noteworthy the finding that patients with valvular heart disease had the highest in-hospital mortality (42.9%) and lowest frequency of heart transplantation (no patient received a transplant).

Table 4. Clinical characteristics of patients according to etiology.

| Clinical characteristics |

Chagas’ Disease N(%)/median (IQR25-75) |

Ischemic Heart Disease N(%)/median (IQR25-75) |

Other Dilated Cardiomyopathies N(%)/median (IQR25-75) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 113 | 137 | 250 | |

| Age (years) | 56 (45–63) | 63 (57–71) | 53.5 (41–64) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.01 | |||

| Male | 63 (55.8) | 99 (72.3) | 147(58.8) | |

| Female | 50 (44.2) | 38 (27.7) | 103 (41.2) | |

| Admission diagnosis | <0.001 | |||

| Progressive heart failure | 63 (55.8) | 63 (46) | 177 (70.8) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 17 (15) | 16 (11.7) | 29 (11.6 | |

| Arrhythmia/Syncope | 23 (20.4) | 19 (13.9) | 11 (4.4) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 2 (1.8) | 14 (10.2) | 6 (2.4) | |

| Infections | 2 (1.8) | 8 (5.8) | 5 (2.0) | |

| Others | 6 (5.3) | 17 (12.4) | 22 (8.8) | |

| Symptoms at admission | ||||

| Orthopnea | 54 (47.8) | 54 (39.4) | 135 (54) | 0.023 |

| NPD | 47 (41.6) | 50 (36.5) | 123 (49.2) | 0.046 |

| Chest pain | 30 (26.5) | 41 (29.9) | 72 (28.8) | 0.837 |

| Syncope | 25 (22.1) | 19 (13.9) | 30 (12) | 0.04 |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 10 (3–31) | 7 (1–30) | 14(3–31) | 0.035 |

| Physical exam | ||||

| Lower limbs edema | 59 (52.2) | 68 (49.6) | 146 (58.4) | 0.215 |

| Pulmonary rales | 33 (29.2) | 65 (47.4) | 132 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| Jugular distension | 70 (61.9) | 54 (39.4) | 139 (55.6) | 0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 55 (48.7) | 35 (25.5) | 107(42.8) | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 31 (27.4) | 28 (20.4) | 51 (20.4) | 0.285 |

| Mitral systolic murmur | 43 (38.1) | 29 (21.2) | 80 (32) | 0.011 |

| Tricuspid systolic murmur | 14 (12.4) | 9 (6.6) | 22 (8.8) | 0.275 |

| Third heart sound | 7 (6.2) | 5 (3.6) | 18 (7.2) | 0.37 |

| Inadequate perfusion | 51 (45.1) | 37 (27) | 89 (35.6) | 0.012 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72 (60.5–88.5) | 79 (65.5–98) | 85 (70–103) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 90 (80–100) | 100 (88–120) | 100 (83–110) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 61 (55–72) | 65 (60–80) | 63 (60–77) | 0.512 |

bpm: beats per minute; BP: blood pressure; mm Hg: millimeters of mercury; NPD: nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnea

Fig 1. In-Hospital outcomes according to heart failure etiology.

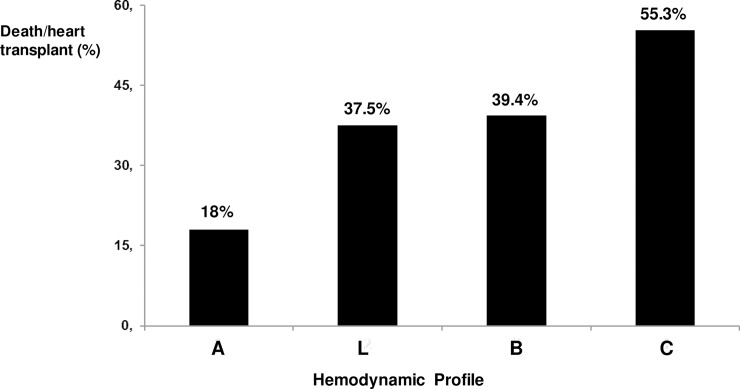

We further analyzed patients according to the presence of specific hemodynamic profiles, based on clinical findings, as previously described: profile A (72 [14.4%] patients), profile B (251 [50.2%] patients), profile C (161 [32.2%] patients), and profile L (16 [3.2%] patients). Profiles B and C were associated with increased chance of heart transplant or death during hospital admission (39.4% and 55.3%, respectively) (Fig 2). The distribution of the hemodynamic findings varied according to heart failure etiology (Fig 3): profile C was more frequent in patients with Chagas as compared to other etiologies.

Fig 2. In-hospital prognosis according to hemodynamic profile.

Profile A: patients with no evidence of congestion or hypoperfusion (dry-warm); profile L: patients with hypoperfusion without congestion (dry-cold); profile B: patients with congestion with adequate perfusion (wet- warm); profile C: patients with congestion and hypoperfusion (wet-cold).

Fig 3. Distribution of the hemodynamic profile according to etiology.

Analysis according to ventricular function

When clinical characteristics of patients were analyzed according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (Table 5), we found that patients with LVEF≥40%, compared with patients with LVEF<40%, were older (63 years [IQ25-75% 55–76 versus 57 years, IQ25-75% 45–64], respectively, P<0.001), were more frequently female (49.5% versus 45.5%, respectively, P = 0.014) and had a higher frequency of ischemic heart disease (34% versus 25.8%, respectively, P<0.001). Symptoms of orthopnea (34% versus 52.1%, respectively, P = 0.001) and nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnea (28.9% versus 47.6%, respectively, P = 0.001) were less frequent among patients with preserved LVEF compared with patients with reduced LVEF, as well as signs of right side congestion (73.2% versus 84.6%, respectively, P = 0.011); finally, blood pressure was higher among patients with preserved LVEF compared with patients with reduced LVEF (110 mm Hg, [IQ25-75% 94–127 versus 92 mmHg, IQ25-75% 80–110], respectively, P<0.001).

Table 5. Clinical characteristics of patients according to cardiac function.

| Clinical characteristics | LV Ejection Fraction <40% N(%)/median(IQR25-75) | LV Ejection Fraction ≥40% N(%)/median(IQR25-75) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 403 | 97 | |

| Age (years) | 57 (45–64) | 63 (55–76) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.014 | ||

| Male | 260 (64.5) | 49 (50.5) | |

| Female | 143 (45.5) | 48 (49.5) | |

| Admission diagnosis | 0.174 | ||

| Progressive heart failure | 247 (61.3) | 56 (57.5) | |

| Cardiogenic shock | 56 (13.9) | 6 (6.2) | |

| Arrhythmia/Syncope | 39 (9.7) | 14 (14.4) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 16 (4) | 6 (6.2) | |

| Infections | 11 (2.7) | 4 (4.1) | |

| Others | 34 (8.4) | 11 (11.3) | |

| Heart failure etiology | 0.014 | ||

| Chagas Heart Disease | 101 (25.1) | 12 (12.4) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 104 (25.8) | 33 (34) | |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 198 (49.1) | 52 (53.6) | |

| Previous history | |||

| Hypertension | 202 (50.1) | 60 (61.9) | 0.042 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 123 (30.5) | 33 (34) | 0.542 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 140 (34.7) | 39 (40.2) | 0.346 |

| Symptoms at admission | |||

| Orthopnea | 210 (52.1) | 33 (34) | 0.001 |

| NPD | 192 (47.6) | 28 (28.9) | 0.001 |

| Chest pain | 117 (29) | 26 (26.8) | 0.709 |

| Syncope | 63 (15.6) | 11 (11.3) | 0.341 |

| Duration of symptoms (days) | 12 (3–31) | 7 (1–31) | 0.149 |

| Physical exam | |||

| Any sign of congestion | 341 (84.6) | 71 (73.2) | 0.011 |

| Lower limbs edema | 225 (55.8) | 48 (49.5) | 0.307 |

| Pulmonary rales | 184 (45.7) | 46 (47.4) | 0.821 |

| Jugular distension | 228 (56.5) | 35 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Hepatomegaly | 170 (42.2) | 27 (27.8) | 0.011 |

| Ascites | 95 (23.6) | 15 (15.5) | 0.101 |

| Mitral systolic murmur | 132 (32.8) | 20 (20.6) | 0.020 |

| Tricuspid systolic murmur | 34 (8.4) | 11 (11.3) | 0.428 |

| Third heart sound | 30 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 0.002 |

| Inadequate perfusion | 153 (38) | 24 (24.7) | 0.018 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 81 (68–100) | 78 (68–95) | 0.198 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 92 (80–110) | 110 (94–127) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 60 (57–72) | 70 (60–80) | 0.004 |

bpm: beats per minute; BP: blood pressure; mm Hg: millimeters of mercury; NPD: nocturnal paroxysmal dyspnea

Discussion

The present study sought to analyze the importance of clinical findings in a contemporaneous cohort of patients admitted with decompensated heart failure. The strengths of our study are based, first, on the finding that clinical characteristics of patients remain important for prognostic evaluation in a contemporaneous cohort of high-risk patients with advanced heart failure; second, clinical characteristics at presentation vary according to heart failure etiology, particularly among patients with Chagas disease, and according to left ventricular function, findings with significant clinical and therapeutic implications.

In the present cohort, median age was 58 years, patients were predominantly male (61.8%), and there was a high proportion of Chagas etiology (22.6%). It is important to note that in-hospital mortality was high (30.8%). These findings markedly contrast with reports from other authors. Data from the ADHERE registry that included patients from the United States showed a mean age of 72 years, a higher prevalence of female patients, and ischemic heart disease as the main etiology. Significantly, the in-hospital mortality reported was 4%.[19] Similarly, data from a European registry reported mean age 70±13 years and a predominance of male patients. The total in-hospital mortality rate was 3.8%.[20] Data from the Brazilian Registry of patients with decompensated heart failure reported a mean age of 64 years, a predominance of male patients, and in-hospital mortality of 12.6%.[21] Therefore, it should be noted that our study included a relatively young population with advanced heart failure. Possible reasons for these discrepancies are the inclusion of a high proportion of patients with Chagas heart disease that tend to affect a younger population compared with other forms of heart disease, especially ischemic heart disease.[22] Even though few other studies reported on the comparative outcomes of patients with Chagas heart disease and other etiologies, data from studies with patients with chronic heart failure indicate that Chagas patients have a worse prognosis compared with patients with hypertensive and ischemic heart disease[13,23,24] which may have contributed to the excessive mortality we have found. In the setting of decompensated heart failure, a recent study compared the prognosis of patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy to that of patients with other etiologies; no difference was found regarding in-hospital mortality, but Chagas patients had a higher rate of hospital readmission.[25] Additionally, our center is a tertiary hospital dedicated to cardiology that treats patients with advanced heart failure, with a higher expected mortality compared with that in community hospitals. In this sense, it is remarkable that a third of our patients received inotropes during their hospital stay.

We found that clinical findings at admission could identify patients with a worse prognosis during hospital stay, in particular, presence of cardiogenic shock, low arterial blood pressure and the presence of jugular distension. These findings are in accordance with previous reports and point to the importance of clinical examination of patients with acute decompensated heart failure. In the ADHERE registry, the presence of systolic blood pressure under 125 mm Hg was associated with a worse prognosis in patients with reduced ejection fraction, as well as in patients with preserved ejection fraction. Other clinical variables associated with prognosis in other studies were heart rate, dyspnea at rest, age, diabetes, and ischemic etiology.[26,27]

We found that the clinical presentation of patients was markedly influenced by heart failure etiology. Specifically, Chagas patients had the highest proportion of hospital admissions for cardiogenic shock (15%) and arrhythmia (20.4%), were more hypotensive, and had a higher proportion of patients with signs of right ventricular heart failure such as ascites (27.4%), hepatomegaly (48.7%) and jugular distension (61.9%). These findings suggest that right ventricular dysfunction may be more frequent in Chagas patients. Another study reported the presence of lower limb edema in 94.6% and of jugular engorgement of 48.6% in 37 Chagas patients as compared to 85.9% and 37.4%, respectively, in 99 patients with other etiologies; the differences were not statistically significant, what might be partially explained by the relatively small number of patients.[25] The finding of right ventricular dysfunction has been consistently described among patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy with and without heart failure.[28,29,30] Previous authors have described that pulmonary congestion is a rare phenomenon among Chagas patients and with a mild presentation.[31,32] Mechanisms related to this finding are largely unknown, but may be related to lower arterial blood pressure, autonomic dysfunction or modifications in left ventricular compliance.

Interestingly, when patients were categorized according to hemodynamic profile, Chagas had a higher proportion of patients with the C profile. Few other studies explored the association between heart failure etiology and clinical findings. A previous study[25] that included patients with Chagas heart disease found a higher occurrence of cardiogenic shock or arrhythmia during hospitalization, lower blood pressure, and a higher proportion of signs of right ventricular heart failure compared with other etiologies. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has explored the hemodynamic profile of Chagas patients in episodes of acute decompensation, a finding with significant therapeutic implications.

We found that the outcomes of patients were also markedly influenced by heart failure etiology and hemodynamic profile. Specifically, Chagas patients had the lowest proportion of hospital discharge, and the highest proportion of cardiac transplant when compared to other etiologies; therefore the worse prognosis of these patients is more related to the necessity of heart transplantation due to the severity of decompensation, reflected on clinical findings, than death during hospitalization. Few other studies explored the association between heart failure etiology and outcomes, and previous comparisons between ischemic versus nonischemic heart failure found lower survival in patients with ischemic heart disease. [33,34,35] In this respect, other studies have reported a worse prognosis among Chagas patients admitted with decompensated heart failure, including excessive mortality and higher rates of readmission.[25,36] Our data confirm that Chagas patients do have a worse prognosis during episodes of acute decompensated heart failure. Different mechanisms have been proposed for the worse prognostic found in patients with Chagas, and most data is derived from patients with chronic heart failure.[37] These mechanisms may include increased rate of right ventricular dysfunction, ventricular arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities as well and thromboembolic events[38,39]

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings indicate that the physical exam may identify patients at higher risk in a contemporaneous patient population. Our findings reinforce the need of specific therapeutic approaches targeted at Chagas patients in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure, as they represent a more vulnerable population.

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged; we included a limited number of patients compared with other cohorts reported, and we did not include consecutive patients; therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias. Additionally, as clinical data was obtained from medical records, heterogeneity regarding information from anamnesis and physical examination cannot be excluded. Prognostic information of patients was limited to the admission period, and our data may not be applicable to longer-term follow-up. Finally, some particular characteristics of our population, specifically the younger age and high proportion of patients with Chagas disease, may hinder the applicability of our results to other populations.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study has been funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo. The grant number related to this study is 2015/13063-6. The URL of the funder's website is http://www.fapesp.br. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Reilly BM. Physical examination in the care of medical inpatients: an observational study. Lancet 2003;362:1100–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14464-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeMaria AN. Wither the cardiac physical examination? J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:2156–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elder A, Japp A, Verghese A. How valuable is physical examination of the cardiovascular system? BMJ 2016;354:i3309 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart Fail 2016;18:891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Keuleaner GW, Brutsaert DL. The heart failure spectrum: time for a phenotype-oriented approach. Circulation 2009;119:3044–3046. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbustini E, Narula N, Tavazzi L, Serio A, Grasso M, Favalli V, Bellazzi R, Tajik JA, Bonow RO, Fuster V7. The MOGE(S) classification of cardiomyopathy for clinicians. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:304–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minami Y, Kajimoto K, Sato N, Aokage T, Mizuno M, Asai K, Munakata R, Yumino D, Murai K, Hagiwara N, Mizuno K, Kasanuki H, Takano T. Third heart sound in hospitalised patients with acute heart failure: insights from the ATTEND study. 2015;69:820–8. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambrosy AP, Pang PS, Khan S, Konstam MA, Fonarow GC, Traver B, Maggioni AP, Cook T, Swedberg K, Burnett JC Jr, Grinfeld L, Udelson JE, Zannad F, Gheorghiade M; EVEREST Trial Investigators. Clinical course and predictive value of congestion during hospitalization in patients admitted for worsening signs and symptoms of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: findings from the EVEREST trial. Eur Heart J 2013;34:835–43. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho JE, Gona P, Pencina MJ, Tu JV, Austin PC, Vasan RS, Kannel WB, D’Agostino RB, Lee DS, Levy D. Discriminating clinical features of heart failure with preserved vs reduced ejection fraction in the community. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1734–1741. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbs FD, Roalfe AK, Davis RC, Davies MK, Hare R. Midlands Research Practices Consortium (MidReC). Prognosis of all-cause heart failure and borderline left ventricular systolic dysfunction: 5 year mortality follow-up of the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening Study (ECHOES). Eur Heart J 2007;28:1128–1134. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal DI, Verghese A. Meaning and the Nature of Physicians’ Work. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1813–1815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kajimoto K,Minami Y, Sato N, Kasanuki H. Etiology of heart failure and outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol 2016;118:1881–1887. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.08.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vilas Boas LG1, Bestetti RB, Otaviano AP, Cardinalli-Neto A, Nogueira PR. Outcome of Chagas cardiomyopathy in comparison to ischemic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Requena-Méndez A1, Aldasoro E1, de Lazzari E1, Sicuri E1, Brown M2, Moore DA2, Gascon J1, Muñoz J1. Prevalence of Chagas disease in Latin-American migrants living in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(2):e0003540 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bocchi EA, Bestetti RB, Scanavacca MI, Cunha Neto E, Issa VS. Chronic Chagas Heart Disease Management: From Etiology to Cardiomyopathy Treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol;70(12):1510–1524 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara P, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: Framingham study. N Engl J Med 1971;285:1441–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freitas HF, Chizzola PR, Paes AT, Lima AC, Mansur AJ. Risk stratification in a Brazilian hospital-based cohort of 1220 outpatients with heart failure: role of Chagas' heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2005;102:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nohria A, Tsang SW, Fang JC, Lewis EF, Jarcho JA, Mudge GH, Stevenson LW. Clinical assessment identifies hemodynamic profiles that predict outcomes in patients admitted with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, Berkowitz RL, LeJemtel TH, Cheng ML, Wynne J; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators; ADHERE Study Group. In-hospital mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure requiring intravenous vasoactive medications: an analysis from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Targher G, Dauriz M, Laroche C, Temporelli PL, Hassanein M, Seferovic PM, Drozdz J, Ferrari R, Anker S, Coats A, Filippatos G, Crespo-Leiro MG, Mebazaa A, Piepoli MF, Maggioni AP, Tavazzi L; ESC-HFA HF Long-Term Registry investigators. In-hospital and 1-year mortality associated with diabetes in patients with acute heart failure: results from the ESC-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:54–65. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albuquerque DC, Neto JD, Bacal F, Rohde LE, Bernardez-Pereira S, Berwanger O, Almeida DR; Investigadores Estudo BREATHE. I Brazilian Registry of Heart Failure—clinical aspects, care quality and hospitalization outcomes. Arq Bras Cardiol 2015;104:433–42. doi: 10.5935/abc.20150031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bocchi EA, Arias A, Verdejo H, Diez M, Gómez E, Castro P; Interamerican Society of Cardiology. The reality of heart failure in Latin America. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:949–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bestetti RB, Otaviano AP, Fantini JP, Cardinalli-Neto A, Nakazone MA, Nogueira PR. Prognosis of patients with chronic systolic heart failure: Chagas disease versus systemic arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2990–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Issa VS, Amaral AF, Cruz FD, Ferreira SM, Guimarães GV, Chizzola PR, Souza GE, Bacal F, Bocchi EA. Beta-blocker therapy and mortality of patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy: a subanalysis of the REMADHE prospective trial. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:82–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.882035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos LN, Rocha MS, Oliveira EN, Moura CA, Araujo AJ, Gusmão ÍM, Feitosa-Filho GS, Cruz CM. Decompensated chagasic heart failure versus non-chagasic heart failure at a tertiary care hospital: Clinical characteristics and outcomes. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2017;63:57–63. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.01.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, De Marco, Fonarow GC; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crespo-Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, Coats AJ, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, Ferrari R, Piepoli MF, Delgado Jimenez JF, Metra M, Fonseca C, Hradec J, Amir O, Logeart D, Dahlström U, Merkely B, Drozdz J, Goncalvesova E, Hassanein M, Chioncel O, Lainscak M, Seferovic PM, Tousoulis D, Kavoliuniene A, Fruhwald F, Fazlibegovic E, Temizhan A, Gatzov P, Erglis A, Laroche C, Mebazaa A; Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:613–25. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreira HT, Volpe GJ, Marin-Neto JA, Ambale-Venkatesh B, Nwabuo CC, Trad HS, Romano MM, Pazin-Filho A, Maciel BC, Lima JA, Schmidt A. Evaluation of Right Ventricular Systolic Function in Chagas Disease Using Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10(3). pii: e005571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furtado RG, Frota Ddo C, Silva JB, Romano MM, Almeida Filho OC, Schmidt A, Rassi S. Right ventricular Doppler echocardiographic study of indeterminate form of chagas disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;104:209–17 doi: 10.5935/abc.20140197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunes Mdo C, Barbosa Mde M, Brum VA, Rocha MO. Morphofunctional characteristics of the right ventricle in Chagas' dilated cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2004. March;94(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barral MM, Nunes Mdo C, Barbosa MM, Ferreira CS, Tavares WC Jr, Rocha MO. Echocardiographic parameters associated with pulmonary congestion in outpatients with Chagas' cardiomyopathy and non-chagasic cardiomyopathy. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012;45(2):215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocha MO, Nunes MC, Ribeiro AL. Morbidity and prognostic factors in chronic chagasic cardiopathy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009;104 Suppl 1:159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shore S, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Eapen ZJ, Hernandez AF, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Characteristics, Treatments, and Outcomes of Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients Stratified by Etiologies of Cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2015. November;3:906–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostręga M, Gierlotka MJ, Słonka G, Nadziakiewicz P, Gąsior M. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of patients with ischemic and nonischemic acute severe heart failure. Analysis of data from the COMMIT-AHF registry. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2017. May 31;127(5):328–335 doi: 10.20452/pamw.3996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lourenço C, Saraiva F, Martins H, Baptista R, Costa S, Coelho L, Vieira H, Monteiro P, Franco F, Gonçalves L, Providência LA. Ischemic versus non-ischemic cardiomyopathy—are there differences in prognosis? Experience of an advanced heart failure center. Rev Port Cardiol. 2011. February;30(2):181–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochiai ME, Cardoso JN, Vieira KR, Lima MV, Brancalhao EC, Barretto AC. Predictors of low cardiac output in decompensated severe heart failure. Clinics 2011;66:239–44. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000200010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Issa VS, Amaral AF, Cruz FD, Ferreira SM, Guimarães GV, Chizzola PR, Souza GE, Bacal F, Bocchi EA. Beta-blocker therapy and mortality of patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy: a subanalysis of the REMADHE prospective trial. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3(1):82–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.882035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayub-Ferreira SM, Mangini S, Issa VS, Cruz FD, Bacal F, Guimarães GV, Chizzola PR, Conceição-Souza GE, Marcondes-Braga FG, Bocchi EA. Mode of death on Chagas heart disease: comparison with other etiologies. a subanalysis of the REMADHE prospective trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(4):e2176 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribeiro AL, Nunes MP, Teixeira MM, Rocha MO . Diagnosis and management of Chagas disease and cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:576–589. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.