Abstract

The archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus is emerging as a metabolic engineering platform for production of fuels and chemicals, such that more must be known about this organism’s characteristics in bioprocessing contexts. Its ability to grow at temperatures from 70 to greater than 100°C and thereby avoid contamination, offers the opportunity for long duration, continuous bioprocesses as an alternative to batch systems. Towards that end, we analyzed the transcriptome of P. furiosus to reveal its metabolic state during different growth modes that are relevant to bioprocessing. As cells progressed from exponential to stationary phase in batch cultures, genes involved in biosynthetic pathways important to replacing diminishing supplies of key nutrients and genes responsible for the onset of stress responses were up-regulated. In contrast, during continuous culture, the progression to higher dilution rates down-regulated many biosynthetic processes as nutrient supplies were increased. Most interesting was the contrast between batch exponential phase and continuous culture at comparable growth rates (~0.4 h−1), where over 200 genes were differentially transcribed, indicating among other things, N-limitation in the chemostat and the onset of oxidative stress. The results here suggest that cellular processes involved in carbon and electron flux in P. furiosus were significantly impacted by growth mode, phase and rate, factors that need to be taken into account when developing successful metabolic engineering strategies.

Keywords: Pyrococcus furiosus, hyperthermophiles, continuous culture, growth phase, growth rate, transcriptome

Extremely thermophilic archaea and bacteria are distinguished from other microorganisms by their ability to grow optimally at temperatures of 70°C and above. Although extreme thermophiles were isolated and described nearly 50 years ago, their known diversity expanded considerably in the 1980s and 1990s as discoveries made it clear that thermal microbial biotopes contained a broad range of physiological and metabolic features. Recent advances in the development of molecular genetics tools for extreme thermophiles have focused their interest on the prospects of using these microorganisms as metabolic engineering platforms for bio-based fuels and chemicals (Zeldes et al. 2015). Indeed, the extremely thermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus (Fiala and Stetter 1986) has been engineered to produce 3-hydroxypropionate (3-HP), n-butanol acetoin, ethanol, and to produce H2 from formate and carbon monoxide (Adams and Kelly 2017). However, further efforts with high temperature bioprocessing for biotechnology applications will require better understanding of the metabolic and physiological features of non-model microorganisms.

Prior to the development of genetics tools for P. furiosus, transcriptomic analyses were valuable for gaining insights into the growth physiology under a range of conditions, including peptide fermentation, heat shock, cold shock, exposure to gamma radiation, and oxidative stress. Variations in the transcriptome were also used to monitor genetic exchange at high temperatures, to re-annotate the genome, evaluate starch metabolism, determine carbohydrate substrate preference, identify genes related to glucan-degrading enzymes, measure the effects of a spontaneous mutation on motility, and examine the functionality of genetically modified strains. In all of these cases, except one (Chou et al. 2007), batch culture provided samples for analysis, and growth phase and growth rates were not considered. Given that P. furiosus can be cultured in a continuous bioprocessing operation for long durations with minimal contamination risk, important questions arise on how growth mode, growth phase, and growth rate impact P. furiosus growth physiology.

P. furiosus was grown in batch culture at 90°C to compare exponential (E) (5 hours, 5 × 107 cells/mL), early stationary (ES) (8 hours, 9.5 × 107 cells/mL), and late stationary (LS) (16 hours, 1.2 × 108 cells/mL) phase transcriptomes (see Table I). In batch culture, 92 genes were up-regulated and 40 genes down-regulated when LS phase was compared to E phase (Table II). Entrance into ES resulted in up-regulation of 64 genes relative to E, and 40 genes were down-regulated in E relative to ES (Table I). Most of the up-regulated genes in ES or LS compared to E were related to de novo synthesis of cellular building blocks (e.g., cofactors and amino acids), presumably reaching limiting concentrations (Table II). For example, PF1529, which encodes a pyridoxine biosynthesis protein, was up-regulated 14-fold during the transition from E to ES, while genes implicated in thiamine anabolism (PF1333-1338) were up-regulated as much as 20-fold in LS (Table II). On the other hand, many genes implicated in the catabolism of amino acids, such as acyl-CoA synthetase (PF0532), indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductasee (IOR, PF0533), 2-ketoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase (KGOR, PF1767-1770) and a putative ferredoxin oxidoreductase of unknown specificity (PF1771-1773), were strongly down-regulated in stationary phase (Table SI). Taken together, these results show that upon approaching and entering stationary phase, several biosynthetic pathways in P. furiosus were induced to replenish the diminishing supply of key growth factors, while at the same time catabolic functions were minimized.

Table 1. Growth phase and growth rate effects on P. furiosus transcriptome.

Listed are ORFS changing 8-fold or more for any contrast; LS: late stationary phase at 16 h after inoculation, ES: early stationary phase at 8 h after inoculation, E: exponential phase at 5 h after inoculation. For continuous cultures, dilution rates are denoted as the following: D1 = 0.15 h−1; D2 = 0.25 h−1; D4 = 0.45 h−1.

| Function | Gene ID | Annotation | Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BATCH CULTURE CONTRASTS | ES vs. E | LS vs. E | LS vs. E | ||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | PF1053 | aspartate kinase | 7 | --- | 8 |

| PF1055 | threonine synthase | 9 | --- | 9 | |

| PF1951 | asparagine synthetase A | 30 | --- | 16 | |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers | PF1333 | phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase | --- | 8 | 9 |

| PF1335 | hydroxyethylthiazole kinase | --- | 12 | 9 | |

| PF1337 | transcriptional activator, TenA (thiamine biosynthesis) | --- | 14 | 20 | |

| PF1338 | transcriptional activator, TenA family | --- | 21 | 17 | |

| PF1529 | pyridoxal biosynthesis lyase, pdxS | 14 | --- | 20 | |

| PF1530 | thiazole biosynthetic enzyme | --- | 10 | 12 | |

| Cellular processes | PF1557 | universal stress protein A (USPA) | --- | 13 | 17 |

| Energy Metabolism | PF1975 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 10 | --- | 7 |

| CONTINUOUS CULTURE CONTRASTS | D2 vs. D1 | D4 vs. D2 | D4 vs. D1 | ||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | PF1052 | serine/threonine biosynthesis | --- | 5 ↓ | 8↓ |

| PF1266 | cystathionine gamma-synthase | --- | 18↓ | 11↓ | |

| PF1267 | 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | --- | 15↓ | 9↓ | |

| PF1268 | homosysteine methyltransferase | --- | 8↓ | 5↓ | |

| Biosynthesis of cofactors, prosthetic groups, and carriers | PF1528 | pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase PdxT | 3↓ | 5↓ | 15↓ |

| PF1529 | pyridoxal biosynthesis protein | --- | 29↓ | 38↓ | |

| Cell envelope | PF0489 | hypothetical membrane protein | 14↓ | --- | 11↓ |

| Cellular processes | PF1033 | alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | 3 | 5 | 14 |

| Energy metabolism | PF0477 | extracellular alpha amylase | 3 | 17 | 50 |

| Purines, pyrimidines, nucleosides, and nucleotides | PF0421 | 5-formaminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-(beta)-D-ribofuranosyl 5′-monophosphate synthetase | --- | 19↓ | 29↓ |

| PF0422 | phosphoribosylamine-glycine ligase | --- | 13↓ | 12↓ | |

| PF0426 | phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase | --- | 7↓ | 8↓ | |

| PF0427 | phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase | 2↓ | 4↓ | 8↓ | |

| PF0430 | phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase | 2 | 36↓ | 16↓ | |

| PF1516 | GMP synthase | --- | 10↓ | 6↓ | |

| Unclassified | PF0449 | glutamine metabolism | 10↓ | --- | 10↓ |

| CONTINUOUS (D4) VS. BATCH (0.45 hr−1) CONTRASTS | D4 vs. E | ||||

| Amino acid biosynthesis | PF0450 | glutamine synthetase I | 8 | ||

| PF1711 | indoleglycerol phosphate synthase | 8 | |||

| PF1951 | asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase | 42 | |||

| Oxidative stress | PF1033 | alkyl hydroperoxide reductase | 17 | ||

| Hypothetical | PF1347 | small peptide, 88AA | 13 | ||

In addition, growth phase transitions also impacted nearly two-dozen genes encoding hypothetical proteins, many of which are unique to the archaea and the Thermococcales. A number of these correspond to short open reading frames (ORFs) encoding proteins of less than 100 aa (see Table SII); a similar observation was made for T. maritima where several short ORFs responded to nutritional limitations (Frock et al. 2012). For example, PF1347, a peptide of 88 residues and unique to the order Thermococcales, was up-regulated 6-fold in ES. Its neighboring gene, PF1346, is a homolog to a membrane-bound PrgY pheromone shutdown protein, which can interfere with self-induction of a small peptide hormone secreted by Enterococcus faecalis via an unknown mechanism (Buttaro et al. 2000).

Growth rate effects on the P. furiosus transcriptome were also examined using continuous culture. Dilution rates of 0.15 (low), 0.25 (medium) and 0.45 (high) h−1 were employed. Note that washout was observed at dilution rates slightly above 0.45 h−1 (data not shown). Cell densities were found to consistently lie between 2.0–2.4 × 108 cells/mL for all dilution rates (see Table I). The P. furiosus transcriptome from two independent continuous cultures operated at a dilution rate of 0.45 hr−1 were essentially identical; only one gene was differentially transcribed 2-fold (PF1055) between replicate experiments (data not shown). This result confirmed that the system used here was capable of both mechanical and biological steady state operation. Transcriptome comparisons among the three dilution rates yielded a total of 333 genes differentially regulated (Table SIII). Comparing the lowest (0.15 h−1) to the highest (0.45 h−1) dilution rates, 229 genes (140 up/89 down) were differentially transcribed 2-fold or more (Table I, Table SIII). It was interesting that some genes were transcribed at their highest or lowest levels at the intermediate dilution rate examined (0.25 hr−1). Table II shows that as dilution rate was increased, thereby increasing the supply of nutrients to the culture, many biosynthetic processes were down-regulated. This reflects differences in transcriptomes for growth phase transitions from E to ES to LS. For example, the up-regulation of the genes encoding a soluble hydrogenase (SHI, PF0891-0894) with increasing dilution rate reflects the increase in fermentation intensity and disposal of excess reducing equivalents. An extracellular α-amylase (PF0477) was up-regulated 50-fold at the highest compared to the lowest dilution rate (Table II), suggested that carbohydrate availability triggered a metabolic response.

Evidence of stress response was noted for certain growth conditions. For example, PF1557, which encodes a universal stress response protein (USP), was up-regulated 12-fold in ES and 17-fold in LS (Table II). The product of PF1557 belongs to a conserved protein superfamily found in all domains of life, implicated in oxidative stress response, energy deficiency and adhesion (Kvint et al. 2003). Several gene clusters encoding putative DNA repair enzymes were up-regulated in batch exponential phase when compared to high dilution rate continuous cultures (Table SIV). The gene clusters PF0641-0642 and PF1125-1129 (Table SIV) feature CAS (CRISPR associated proteins) genes (Makarova et al. 2002). Interestingly, the gene encoding for the argonaute protein (PF0537), serving as the “slicer” for the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC), exhibited a transcriptional profile strikingly similar to that of PF1125-PF1129 CAS gene cluster (Table SIV), although the mechanistic implications of this are not clear.

Differential transcription of heat shock protein encoding genes is also indicative of a stress response. Several genes that were previously found to be heat shock-related in P. furiosus (Shockley et al. 2003) responded at the lowest and intermediate dilution rates, including the thermosome (PF1974) (up-regulated 4-fold) (Table SIII). On the other hand, two known stress proteins, small heat shock protein (PF1883) and myo-inositol-1 phosphate synthase (PF1616), were transcribed highest at the intermediate dilution rate (0.25 hr−1) (Table SIII). The heat shock regulon in P. furiosus is driven by a Phr repressor (PF1790) (Vierke et al. 2003) and a TFIIB homolog (PF0687) (Shockley et al. 2003). While PF1790 was slightly up-regulated (~two-fold) in exponential batch culture compared to continuous culture, PF0687 was 4.8-fold higher for the same comparison.

An antioxidative response, consisting of superoxide reductase (PF1281), it’s electron donor rubredoxin (PF1282) (Thorgersen et al. 2012) and peroxiredoxins (PF0722 and PF1033) (Burton et al. 1995), was up-regulated with increasing dilution rate (Table SIII). In particular, PF1033 was up-regulated 14-fold at 0.45 h−1 compared to 0.15 h−1, but was not affected by growth phase transitions (Table SI). PF0722 and PF1033 are thought to utilize the peroxide generated by superoxide reductase (SOR) (PF1281). The possible introduction of small amounts of oxygen into the bioreactor in continuous mode cannot be ruled out given the external feed to the bioreactor, especially at higher dilution rates. While the possibility of O2 toxicity needs to be considered during continuous culture, the high growth temperature of P. furiosus renders poor oxygen solubility and furthermore P. furiosus has developed stress response mechanisms to deal with this issue (Thorgersen et al. 2012). For long-term operation of anaerobic conditions at larger scales, metal or plastic piping would likely be used as feed lines as opposed to the rubber tubing used at smaller scale, thus reducing oxygen contamination.

A key question addressed here was whether growth of P. furious at comparable rates, but in a different mode (batch vs. continuous), would be reflected in the transcriptome. When continuous and batch culture transcriptomes for similar growth rates (~0.4 hr−1 for batch compared to 0.45 hr−1 for continuous) were compared, 229 genes were differentially transcribed, 122 higher in batch and 107 higher in continuous. Growth rate comparisons with batch during ES phase was not included in this study given that growth at this phase is not balanced. Table II shows the ORFs changing 8-fold or more (see Table SIV for additional information). P. furiosus was grown on complex (containing yeast extract), heterotrophic media yet the up-regulation of amino acid biosynthesis genes was consistent with previous chemostat transcriptome studies with E. coli (Hua et al. 2004) and S. cerevisiae (Boer et al. 2003) in which nitrogen limitation was observed. In this study, the cell density was at least two times higher in the continuous culture than in the batch culture (Table I), which may have contributed to nitrogen limitations and thus differences in expression of nitrogen metabolism genes. For example, the significant up-regulation of PF1951, asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase (42-fold for chemostat vs. batch), suggests that the culture was amino acid-limited in the chemostat. Note that this gene was also highly responsive in ES and LS in batch culture. Since members of the Thermococcales are known to use peptides as a N-source (Rinker and Kelly, 1997), the up-regulation of this gene indicates that the culture was likely N-limited. In fact, when P. furiosus was grown in batch culture, supplemented with amino acids, doubling times decreased from 3.5 to 2.5 h and peak cell density doubled (data not shown). Transcriptome response comparisons under nitrogen limitation at low dilution rates during continuous culture and ES during batch culture were not undertaken in this study but should be considered in future work. Evidence in the transcriptome for nutrient limitations beyond nitrogen was not identified.

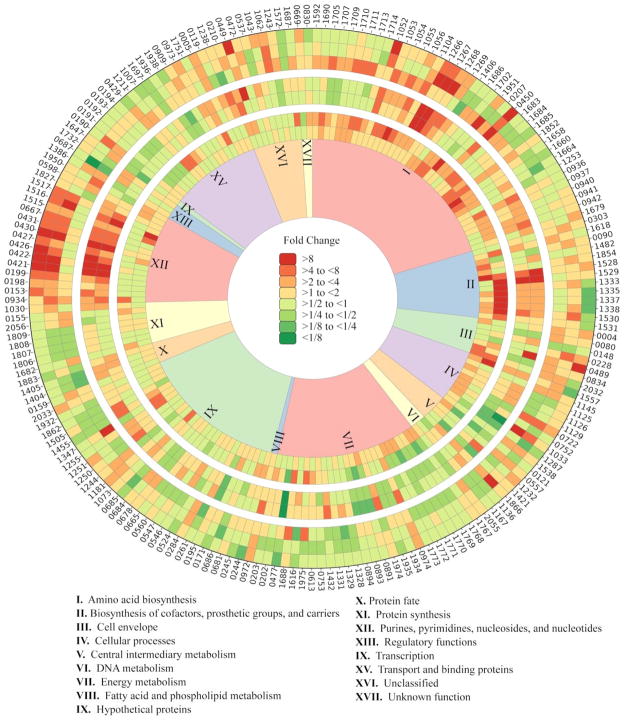

P. furiosus was one of the first extreme thermophiles ever isolated (Fiala and Stetter 1986) and yet specific aspects of its growth physiology have remained unknown. In this report, we shed light on the growth physiology during batch and continuous culture by examining the transcriptome. During P. furiosus growth in batch cultures, stress response genes were up-regulated as were anabolic genes (catabolic genes down-regulated), suggesting the cell’s need to replenish growth factors. Likewise, in continuous cultures of P. furiosus at a low dilution rate (0.15 hr−1), genes implicated in energy metabolism were down-regulated. In contrast, exponential phase growth in batch culture or continuous culture at a high dilution rate (0.45 hr−1), led to an up-regulation of catabolic genes. The heat plot in Figure 1 summarizes the transcriptional response experiments looking at batch vs. continuous culture for P. furiosus. It is clear that growth phase, rate, and mode all impact the transcriptome such that these effects must be accounted for when interpreting phenotype changes in response to environmental perturbations. Recent work involving the metabolic engineering of P. furiosus benefitted from transcriptomic analysis for insights into heterologous gene expression changes and possible bottlenecks for product formation (Hawkins et al. 2015). While different products generated from engineered strains will impact the transcriptome in different ways, this study provides a transcriptome baseline when selecting target products and demonstrates that growth mode, phase and rate considerations could prove critical for steering carbon and electron flux to desired products in engineered strains.

Figure 1. Differentially transcribed ORFs in batch and continuous cultures of Pyrococcus furiosus grown at 90°C in SSM supplemented with maltose.

(Left) Growth of P. furiosus in batch culture with 1.8L working volume on maltose supplemented SSM medium. Arrows indicate sampling times for RNA extraction (5, 8, 16 hours). EXP: exponential phase. ES: early stationary phase. LS: late stationary phase. (Right) Growth of P. furiosus in continuous culture with 1L working volume on maltose supplemented SSM medium at 0.15 hr−1 (■), 0.25 hr−1 (

), and 0.45 hr−1 (▲). The arrow indicates the start of steady state (to); samples for transcriptional analysis were taken after 5 reactor volume changes.

), and 0.45 hr−1 (▲). The arrow indicates the start of steady state (to); samples for transcriptional analysis were taken after 5 reactor volume changes.

Numbers represent transcribed ORFs (≥ 2-fold) for comparisons between column and corresponding row. For example, 64 ORFs were up-regulated in ES phase (8 hours) compared to E phase (5 hours).

Dark gray areas

represent comparisons from batch cultures.

represent comparisons from batch cultures.

Light gray areas

represent comparisons from continuous cultures.

represent comparisons from continuous cultures.

E: exponential phase; ES: early stationary phase;LS: late stationary phase

Materials and Methods

Growth of Pyrococcous furiosus in batch and continuous culture

P. furiosus (DSM3638) was grown anaerobically in either batch or continuous culture at 90°C on sea salts-based medium (SSM) (40 g/L sea salt, 3.1 g/L PIPES, 1 mL trace element solution, and 1 g/L yeast extract (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The pH of base medium (950) was adjusted to 6.8 with NaOH solution and autoclaved. The medium was then supplemented with 50 mL filter-sterilized maltose solution (66 g/L) to a final maltose concentration of 5 g/L. Prior to inoculation, the medium was sparged with N2, heated at 90°C and made anaerobic with 0.6% (by volume) of a 10% sodium sulfide solution. Culture cell density was monitored by fixing samples (1 mL) in 5% glutaraldehyde solution and then counting cells using epifluorescence microscopy (acridine orange stain), paying careful attention to cells with uniform morphology and size to ensure that the cultures under study were healthy.

For batch culture, P. furiosus was first passaged six times in 125 mL serum bottles with a 60 mL working volume. Each transfer was allowed to grow for 12 hours, which typically corresponded to a cell density of 1.5 × 108 cells/mL. Inoculation levels were gradually reduced from 4% to 1% as the culture became acclimated. Batch culture experiments were done in a bioreactor (1.8 L working volume) consisting of a round bottom glass flask with five 24/40 connection necks; this design is the same as described previously for continuous operation (Pysz et al. 2001), but without feed and efflux streams. The reactor was continuously sparged with 0.02 vessel volumes per minute (vvm) of N2 to maintain anaerobic conditions. A Teflon-coated stir bar and a stir plate underneath the heating mantle were used to mix culture contents (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA); the same stirring rate was used for all experiments. Temperature control at 90 ± 1°C was accomplished through a heating element, a type K thermocouple, and a temperature controller (Cole Palmer Instrument, Vernon Hills, IL). The pH of the culture broth was monitored via an autoclavable pH probe and a pH controller (Cole Palmer Instrument, Vernon Hills, IL). To obtain material for transcriptional response analysis, samples were drawn from the reactors of two biological replicates. During exponential phase (E, 5 hours after inoculation) 600 mL was collected, during early stationary phase (ES, 8 hours post inoculation) 400 mL was collected, and at late stationary phase (LS, 16 hours post inoculation) 400 mL was collected. Given the higher cell densities at ES and LS versus E, smaller sample volumes were sufficient. Samples were quickly harvested with a peristaltic pump and then flash frozen in a dry ice bath.

The continuous culture bioreactor configuration (1 L working volume) was the same as described above for batch operation. Starter cultures (30 mL) were prepared as described above; the bioreactor was inoculated at 6 × 106 cells/mL. After 6 hours in batch mode, continuous operation was initiated. The feed and the effluent streams were driven by two independent peristaltic pumps (Cole Palmer Instrument, Vernon Hills, IL), set at the desired volumetric flow rates, through rubber tubing. Feed was provided from a 10 L reservoir maintained at anaerobic conditions through continuous N2 sparging. After 12 hours, the dilution rate was set to 0.15, 0.25 or 0.45 hr−1 (corresponding to doubling times of 4.6, 2.8, and 1.5 h, respectively). Samples for cell counts were taken from the reactor every 2 hours. Cultures usually achieved steady state (based on pH and cell density) after three volume changes; samples for transcriptome analysis were taken after 5 volume changes. Samples for transcriptome analysis were first taken from two biological replicate continuous cultures set at the 0.45 hr−1 dilution rate. Only one ORF changed 2-fold or more between the replicate runs, validating the consistent operation of the bioreactor system at mechanical and biological steady states. Single runs at 0.15 and 0.25 hr−1 were carried out given the long duration time for each continuous culture experiment.

Transcriptomics

Extraction and purification of P. furiosus RNA was performed as previously described (Conners et al. 2005). An equal amount of total RNA (5.5 μg −10.0 μg) from two independent extractions (bioreps) was pooled (11 μg – 20.0 μg) and then used for a reverse transcription reaction. cDNA was generated using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), random primers (Life Technologies), and the incorporation of 5-(3-amino-allyl)-2′-deoxyurinidine-5′-triphosphate (Life Technologies). The reaction mixture was incubated at 46°C for 16 h. The probes for each whole genome microarray were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies, Iowa), re-suspended in 50% dimethyl sufloxide, and printed on Ultragap microarray slides (Corning, New York) using a QArrayMini arrayer (Genetix, United Kingdom). The isolated total RNA was converted to fluorescently-labeled cDNA and hybridized to each respective P. furiosus whole genome DNA microarray slide. The amount of cDNA generated from each RNA extraction varied but was normalized (equal concentrations of each) before hybridization to the slide to minimize variation in the output data. Depending on the experiment, final cDNA normalization values could range from ~50 ng/μl to ~100 ng/μl. For each comparison within each experiment (organism under study), cDNA from one treatment/condition was labeled with either Cyanine-3 dye (Cy3) or Cyanine-5 dye (Cy5) (GE Healthcare) and combined with cDNA from a contrasting treatment/condition labeled with the opposite dye. To control for dye effects, every treatment/condition was labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 in the course of the array loop. For example, in its simplest form (a dye flip), RNA from condition 1 (cy3 labeled) and condition 2 (cy5 labeled) would be combined and hybridized to slide 1 followed by condition 1 (cy5 labeled) and condition 2 (cy3 labeled) which would be combined and hybridized to slide 2. This scenario is expanded when three or more slides form a loop. The combined cDNA samples were then hybridized to a GAPS II coated slide for 18 hours, according to modified TIGR protocols (Hegde et al. 2000). Each slide was then washed and scanned (ScanArrayExpress Scanner, Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA). Spot intensities were quantified by the vendor-supplied software and quality control was confirmed by an RI plot (Cui and Churchill 2003) of raw intensity values. Raw signal intensities were normalized by a mixed effects ANOVA model as described previously (Conners et al. 2005). The Bonferroni significance cut-off equal to or below a −log10 (p-value) of ~5.0 was used to determine statistical significance of genes that were differentially transcribed two-fold or more.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Heat map of log2-fold change comparisons in P. furiosus. Inner ring: batch culture at 8 h and 16 h compared to 5 h (inside to outside). Middle ring: chemostat culture at D = 0.25 h−1 and 0.15 h−1 compared to 0.45 h−1(inside to outside). Outer ring: chemostat compared to batch: D = 0.45 h−1 vs. 5 h, D = 0.25 h−1 vs. 8 h, D = 0.15 h−1 vs. 16 h (inside to outside). Only genes with a 3-fold change for at least one contrast are shown.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the US National Science Foundation (CBET-1264052, CBET-1264053). AJ Loder acknowledges support from an NIH Biotechnology Traineeship (NIH T32GM008776-11).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional supporting information may be found in the on-line version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- Adams MWW, Kelly RM. The renaissance of life near the boiling point - at last, genetics and metabolic engineering. Microbial Biotechnology. 2017;10(1):37–39. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer VM, de Winde JH, Pronk JT, Piper MD. The genome-wide transcriptional responses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae grown on glucose in aerobic chemostat cultures limited for carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(5):3265–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton NP, Williams TD, Norris PR. A potential anti-oxidant protein in a ferrous iron-oxidizing Sulfolobus species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134(1):91–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttaro BA, Antiporta MH, Dunny GM. Cell-associated pheromone peptide (cCF10) production and pheromone inhibition in Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(17):4926–33. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4926-4933.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CJ, Shockley KR, Conners SB, Lewis DL, Comfort DA, Adams MW, Kelly RM. Impact of substrate glycoside linkage and elemental sulfur on bioenergetics of and hydrogen production by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(21):6842–53. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00597-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners SB, Montero CI, Comfort DA, Shockley KR, Johnson MR, Chhabra SR, Kelly RM. An expression-driven approach to the prediction of carbohydrate transport and utilization regulons in the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(21):7267–7282. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7267-7282.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Churchill GA. Statistical tests for differential expression in cDNA microarray experiments. Genome Biol. 2003;4(4):210. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-4-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala G, Stetter KO. Pyrococcus furiosus sp. nov. represents a novel genus of marine heterotrophic archaebacteria growing optimally at 100 degrees C. Arch Microbiol. 1986;145(1):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Frock AD, Gray SR, Kelly RM. Hyperthermophlic Thermotoga species differ with respect to specific carbohydrate transporters and glycoside hydrolases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(6):1978–1986. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07069-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AB, Lian H, Zeldes BM, Loder AJ, Lipscomb GL, Schut GJ, Keller MW, Adams MW, Kelly RM. Bioprocessing analysis of Pyrococcus furiosus strains engineered for CO2-based 3-hydroxypropionate production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112(8):1533–43. doi: 10.1002/bit.25584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde P, Qi R, Abernathy K, Gay C, Dharap S, Gaspard R, Hughes JE, Snesrud E, Lee N, Quackenbush J. A concise guide to cDNA microarray analysis. Biotechniques. 2000;29(3):548–50. 552–4. doi: 10.2144/00293bi01. 556 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Q, Yang C, Oshima T, Mori H, Shimizu K. Analysis of gene expression in Escherichia coli in response to changes of growth-limiting nutrient in chemostat cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(4):2354–66. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2354-2366.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvint K, Nachin L, Diez A, Nystrom T. The bacterial universal stress protein: function and regulation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6(2):140–5. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova KS, Aravind L, Grishin NV, Rogozin IB, Koonin EV. A DNA repair system specific for thermophilic Archaea and bacteria predicted by genomic context analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(2):482–96. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.2.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pysz MA, Rinker KD, Shockley KR, Kelly RM. Continuous cultivation of hyperthermophiles. Methods Enzymol. 2001;330:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)30369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shockley KR, Ward DE, Chhabra SR, Conners SB, Montero CI, Kelly RM. Heat shock response by the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(4):2365–71. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.4.2365-2371.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgersen MP, Stirrett K, Scott RA, Adams MW. Mechanism of oxygen detoxification by the surprisingly oxygen-tolerant hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(45):18547–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208605109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierke G, Engelmann A, Hebbeln C, Thomm M. A novel archaeal transcriptional regulator of heat shock response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):18–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeldes BM, Keller MW, Loder AJ, Straub CT, Adams MW, Kelly RM. Extremely thermophilic microorganisms as metabolic engineering platforms for production of fuels and industrial chemicals. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1209. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.