Abstract

Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum (T. pallidum) causes syphilis via sexual exposure or vertical transmission during pregnancy. T. pallidum is renowned for its invasiveness and immune-evasiveness; its clinical manifestations result from local inflammatory responses to replicating spirochetes and often imitate those of other diseases. The spirochete has a long latent period during which patients have no signs or symptoms, but can remain infectious. Despite the availability of simple diagnostic tests and the effectiveness of treatment with a single dose of long-acting penicillin, syphilis is re-emerging as a global public health problem, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) in high-income and middle-income countries. Syphilis also causes several hundred thousand stillbirths and neonatal deaths every year in developing nations. Although several low-income countries have achieved WHO targets for the elimination of congenital syphilis, an alarming increase of syphilis in HIV-infected MSM serves as a strong reminder of the tenacity of T. pallidum as a pathogen. Strong advocacy and community involvement is needed to ensure that syphilis is given high priority on the global health agenda. More investment in research is needed on the interaction between HIV and syphilis in MSM, as well as into improved diagnostics, a better test of cure, intensified public health measures and, ultimately, a vaccine.

Introduction

Syphilis is a sexually and vertically transmitted infection (STI) caused by the spirochaete Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum (order Spirochaetales) (Fig. 1). Three other organisms within this genus are causes of nonvenereal or endemic treponematoses. T. pallidum subspecies pertenue is the causative agent of yaws, T. pallidum subspecies endemicum causes endemic (non-venereal) syphilis and T. carateum causes pinta. These pathogens are morphologically and antigenically indistinguishable. They can, however, be differentiated by their age of acquisition, principal mode of transmission, clinical manifestations, capacity for invasion of the central nervous system and placenta, and genomic sequences, although the accuracy of these differences remains a subject of debate1. Analyses based on the mutation rates of genomic sequences suggest that the causative agents of yaws and venereal syphilis diverged several thousand years ago from a common progenitor originating in Africa2. These estimates argue against the so-called Columbian hypothesis — the notion that shipmates of Christopher Columbus imported a newly evolved spirochete causing venereal syphilis from the New World into Western Europe in the late 15th century3.

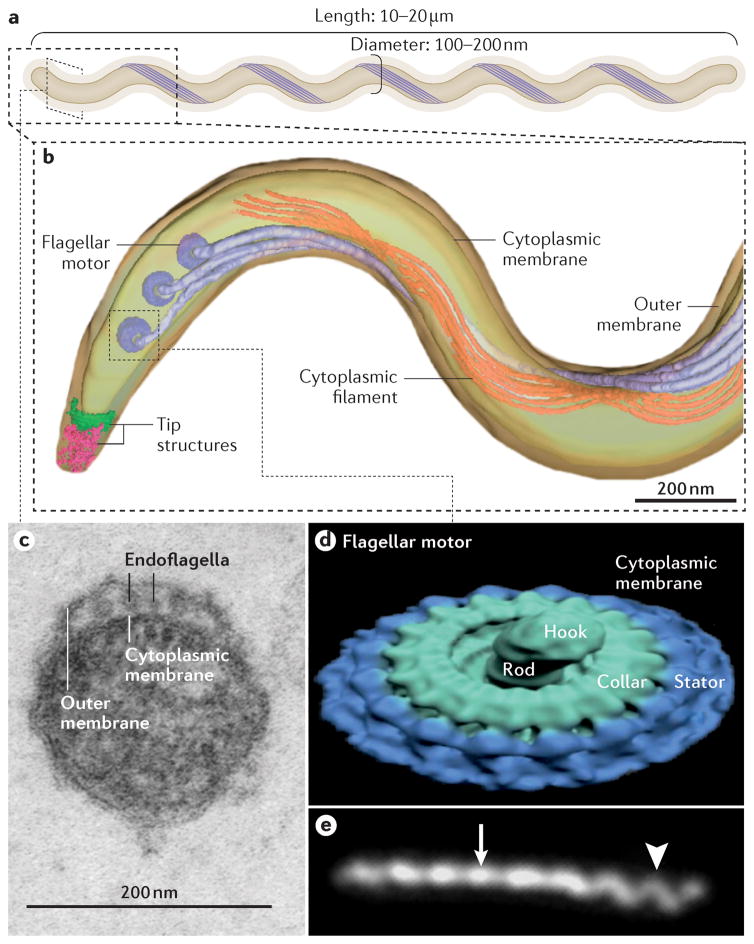

Figure 1. Treponema pallidum.

A | Like all spirochetes, T. pallidum consists of a protoplasmic cylinder and cytoplasmic membrane bounded by a thin peptidoglycan sacculus and outer membrane239,240. Usually described as spiral-shaped, T. pallidum is actually a thin planar wave similar to Borrelia burgdorferi, the agent of Lyme borreliosis239. The bacterium replicates slowly and poorly tolerates desiccation, elevated temperatures and high oxygen tensions55. B | Periplasmic flagellar filaments, a defining morphological feature of spirochetes, originate from nanomotors situated at each pole and wind around the cylinder atop the peptidoglycan, overlapping at mid-cell. Force exerted by the rigid filaments against the elastic peptidoglycan deforms the sacculus to create the flat wave morphology of the spirochete100. Panel B used with permission from Ref.239 C | Ultra-thin section of T. pallidum showing the outer and cytoplasmic membranes and flagellar filaments (endoflagella) within the periplasmic space9. D | Surface rendering of a flagellar motor based on cryoelectron tomograms. Panel D used permission from Ref.240. E | Darkfield micrograph showing the flat-wave morphology of Tpallidum. The arrow and arrowhead indicate segments that are oriented 90° from each other. The different appearances of the helical wave at 90° to the viewer can be explained only by a flat wave morphology; a corkscrew would appear the same from any angle. Panel E used permission from Ref 239.

T. pallidum is an obligate human pathogen renowned for its invasiveness and immunoevasiveness4–7; clinical manifestations result from the local inflammatory response elicited by spirochetes replicating within tissues8–10. Infected individuals typically follow a disease course divided into primary, secondary, latent and tertiary stages over a period of ≥10 years. Different guidelines define early latency as starting 1–2 years after exposure. Typically, ‘early syphilis’ refers to infections that can be transmitted sexually (including primary, secondary and early latent infections) and is synonymous with active (infectious) syphilis; the WHO defines ‘early syphilis’ as infection of <2 years duration11, whereas the guidelines from the United States12 and Europe13 define it as infection <1 year in duration. These differences in definition can affect interpretation of results and in therapeutic regimens used in some circumstances.

Owing to its varied and often subtle manifestations that can mimic other infections, syphilis has earned the names of the Great Imitator or Great Mimicker14. Patients with primary syphilis present with a single ulcer (chancre) or multiple lesions on the genitals or other body sites involved in sexual contact and regional lymphadenopathy ~3 weeks post-infection; these are typically painless and resolve spontaneously. Resolution of primary lesions is followed 6–8 weeks later by secondary manifestations, which can include fever, headache and a maculopapular rash on the flank, shoulders, arm, chest or back and that often involves the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. As signs and symptoms subside, patients enter a latent phase, which can last many years. A patient in the first 1–2 years of latency are still considered infectious owing to a 25% risk of secondary syphilis-like relapses15. Historical literature suggests that 15–40% of untreated individuals will develop tertiary syphilis, which can manifest as destructive cardiac or neurological conditions, severe skin or visceral lesions (gummas) or bony involvement9. More-recent data suggest tertiary syphilis may be less common today, perhaps owing to wide use of antibiotics. Numerous case reports and small series suggest that HIV infection predisposes to neuro-ophthalmological complications in those with syphilis16. Importantly, neurosyphilis is typically described as a late manifestation but can occur in early syphilis. Indeed, T. pallidum can be frequently identified in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) of patients with early disease9,15,17. However, the majority of patients with early syphilis who have CSF abnormalities do not demonstrate central nervous system symptoms and do not require therapy for neurosyphilis12. Symptomatic manifestations of neurosyphilis include chronic meningitis, meningovascular stroke-like syndromes and manifestations common in the neurological forms of tertiary syphilis (namely, tabes dorsalis and general paresis, a progressive dementia mimicking a variety of psychotic syndromes)9.

Sexual transmission of syphilis occurs during the first 1–2 years after exposure (that is, during primary, secondary and early latent stages of infection) 9. The risk of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) is highest in primary and secondary stages, followed by early latent syphilis. However, transmission risk continues during the first 4 years after exposure, after which vertical transmission risk declines over time18. The rate of fetal infection depends on stage of maternal infection, with approximately 30% of pregnancies resulting in fetal death in utero, stillbirth (late second and third trimester fetal death) or death shortly after delivery19–21. Infants born to infected mothers are often preterm, of low birth weight or with clinical signs that mimic neonatal sepsis (that is, poor feeding, lethargy, rash, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly and anaemia).

Given that T. pallidum has a relatively long generation time of 30–33 hours22, long-acting penicillin preparations such as benzathine penicillin G is the preferred therapy for most patients with syphilis. Since the 1940s (when penicillin became widely available), syphilis prevalence continued decline in regions able to appropriately test and treat the infection. However, syphilis outbreaks continue to occur throughout the world. In particular, with declining AIDS-related mortality related to effective HIV treatment over the past two decades, syphilis has re-emerged in urban settings among men who have sex with men (MSM). High-income and middle-income countries have observed rises in syphilis case rates as well as increased case rates of neurosyphilis (such as ocular syphilis) and, in some countries, congenital syphilis. In low income countries where syphilis prevalence remains high, MTCT of syphilis continues to be the most common cause of STI-related mortality outside of HIV23,24, with perinatal deaths owing to untreated syphilis exceeding those of HIV or malaria25. Syphilis is now the second leading cause of preventable stillbirths worldwide, following malaria25.

Syphilis should be an ideal disease for elimination as it has no known animal reservoir, can usually be diagnosed with simple inexpensive tests and can be cured9,16. Nevertheless, syphilis remains a continuing public health challenge globally26. In this Primer, we describe recent discoveries that have improved our understanding of the biological and genetic structure of the pathogen, novel diagnostic tests and testing approaches that can improve disease detection, as well as current, evidence-based management recommendations. We also draw attention to the call for global elimination of MTCT of syphilis and HIV and recent success in elimination in in low and middle income countries (LMICs), particularly through fundamental public health strategies such as ensuring quality antenatal care that includes testing for syphilis early in pregnancy and providing prompt treatment of women and their partners. We also report on the rising numbers of syphilis cases in MSM, ongoing work supporting improved interventions against syphilis in marginalized populations and, ultimately, development of an effective vaccine.

Epidemiology

According to the most recent estimation of the WHO, approximately 17.7 million individuals 15–49 years of age globally had syphilis in 2012, with an estimated 5.6 million new cases every year27 (Fig. 2). The estimated prevalence and incidence of syphilis varied substantially by region or country, with the highest prevalence in Africa and >60% of new cases occurring in LMICs27. The greatest burden of maternal syphilis occurs in Africa, representing >60% of the global estimate23,24.

Figure 2. Incidence of syphilis worldwide.

The WHO estimates of incident cases of syphilis by region in 2012 are shown for the different geographical regions. Data from Ref.27

Prevalence and incidence

In LMICs, heterosexual spread of syphilis has declined in the general population but remains problematic in some high-risk sub-populations, such as female sex workers (FSWs) and their male clients. A recent study of FSWs in Johannesburg, South Africa, showed that 21% of participating women had antibodies that suggested past or current infection and 3% had active (infectious) infection28. Another study of FSWs in 14 zones in Sudan showed high seroprevalence (median 4.1%), with the highest value of 8.9% in the eastern zone of the country29. A large study of >1,000 FSWs in Kampala, Uganda, showed 21% were seropositive for syphilis and 10% had active infection30. Studies in emerging economies, such as China, indicate that syphilis is increasing among ‘mobile men with money’31. Although syphilis case rates are low in the general population in China, syphilis prevalence is ~5% among FSWs and 3% among their male clients31,32. Risk of infection varies among FSWs working in different venues, with the highest prevalence (~10%) among street-based FSWs and lower prevalence (~2%) among venue-based FSWs33.

By contrast, higher-income countries have had declining syphilis prevalence among heterosexual men and women. However, a resurgence of syphilis that disproportionately affects MSM has been noted. Syphilis is associated with high-risk sexual behaviours and substantially increased HIV transmission and acquisition. Indeed, the numbers and rates of reported cases of syphilis among MSM in the United States and Western Europe have been increasing since 1998 (Ref.34). In 2015, the case rates for primary and secondary syphilis among MSM (309 per 100,000) in the United States were 221-times the rate for women (1.4 per 100,000) and 106 times the rate for heterosexual men (2.9 per 100,000)35. In Canada, compared with reported cases in the general male population, the incidence of syphilis was >300-times greater among HIV-positive MSM36. Syphilis infection has been associated with certain behavioural and other factors, including incarceration; multiple or anonymous sex partners; sexual activity connected with illicit drug use; seeking sex partners through the internet and other high-risk sexual network dynamics37–41. Risk factors for syphilis are frequently overlapping40. Reports of unusual presentations and rapid progression of syphilis in patients with concurrent HIV infection has led to the hypothesis that infection with or treatment for HIV alters the natural history of syphilis42.

MTCT

Adverse birth outcomes caused by fetal exposure to syphilis are preventable if women are screened for syphilis and treated before the end of the second trimester of pregnancy21. However, MTCT of syphilis continued to cause such perinatal and infant mortality that, in 2007, the WHO and partners launched a global initiative to eliminate it as a public health problem43–45. At the time of the campaign launch, an estimated 1.4 million pregnant women had active syphilis infections, of whom 80% had attended at least one antenatal visit — suggesting missed opportunities for testing and treatment23. At that time, untreated maternal syphilis infection was estimated to have resulted in >500,000 adverse pregnancy outcomes, including more than 300,000 perinatal deaths (stillbirths and early neonatal deaths).

Syphilis testing and treatment during pregnancy is highly effective and was included in the Lives Saved Tools of effective maternal–child health interventions46. Furthermore, studies have shown that prenatal syphilis screening, treatment support testing and treatment during pregnancy are highly cost-effective in most countries regardless of prevalence or availability of resources, and can even be cost-saving in LMICs with syphilis prevalence ≥3% in pregnant women47–50. In China, where syphilis and HIV prevalence in pregnant women is low but rising, integration of prenatal syphilis and HIV screening was found to be highly cost-effective51.

Since 2007, an increasing number of countries have implemented regional and national initiatives to prevent MTCT of syphilis52, improving guidance documents, using point-of-care (POC) tests as a means of improving access to testing and treatment and integrating behavioural and medical interventions into HIV prevention and control programmes53. By 2012, these efforts had contributed to a reduction in global adverse pregnancy outcomes due to MTCT of syphilis to 350,000, including 210,000 perinatal deaths, and decreased the rates of maternal and congenital syphilis decreased by 38% and 39%, respectively23,24. In 2015, Cuba became the first country to be validated for having achieved elimination of MTCT of HIV and syphilis54. Subsequently, Thailand, Belarus and four United Kingdom Overseas Territories (Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat and Antigua) was validated for elimination of MTCT of HIV and syphilis, Moldova was validated for elimination of MTCT of syphilis, and Armenia was validated for elimination of MTCT of HIV. However, these gains were mostly in Asia and the Americas — maternal prevalence in Africa has remained largely unchanged23,24.

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

Although a local inflammatory response elicited by spirochetes is thought to be the root cause of all clinical manifestations of syphilis9, the mechanisms that cause tissue damage, as well as the host defences that eventually gain a measure of control over the bacterium, are ill defined. The recalcitrance of T. pallidum to in vitro culture and the consequent inability to harness genetic techniques to delineate its virulence determinants remains the primary obstacle to progress55. Additionally, the fragility and low protein content of its outer membrane have confounded efforts to characterize surface-exposed molecules56,57. Finally, facile murine models to dissect the host response and the components of protective immunity are also lacking58. Outbred rabbits are essential for isolating T. pallidum strains from clinical specimens59 and routine propagation in the laboratory60. Because rabbits are highly susceptible to T. pallidum infection, develop lesions grossly and histopathologically resembling chancres following intradermal inoculation and generate antibody responses similar to those in humans, the rabbit is the model of choice for studying endogenous and exogenous protective immunity61,62. However, the rabbit model poorly recapitulates many clinical and immunological facets of human disease63. Not surprisingly, even in the post-genomics era, our understanding of pathogenic mechanisms in syphilis lags well behind other common bacterial diseases63.

Molecular Features

The morphological features of T. pallidum are described in Figure 1. Because of its double-membrane structure, the spirochete is often described as a Gram-negative bacterium. However, this analogy is phylogenetically, biochemically and ultrastructurally inaccurate63,64. The T. pallidum outer membrane lacks lipopolysaccharide65 and has a markedly different phospholipid composition than the outer membranes of typical Gram-negative bacteria66. Although T. pallidum expresses abundant lipoproteins, these molecules reside predominantly below the surface5,63,67. Accordingly, this paucity of surface-exposed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) enables the spirochete to avoid triggering host innate surveillance mechanisms, facilitating local replication and early dissemination. Its limited surface antigenicity promotes evasion of adaptive immune responses (that is, antibodies), facilitating persistence5,56,68,69. Collectively, these attributes have earned T. pallidum its designation as ‘the stealth pathogen’63,69. Understanding events unfolding at the host–pathogen interface requires a detailed knowledge of the T. pallidum repertoire of surface-exposed proteins. However, characterization of the protein constituents of the outer membrane has been, and continues to be, daunting8,55,57,63.

Lipoproteins

In the 1980s, investigators screened E. coli recombinant libraries with syphilitic sera and murine monoclonal antibodies based upon the unproven (and, as it turned out, immunologically incorrect) assumption that immunoreactive proteins ought to be surface-exposed in T. pallidum57. Biochemical and genetic analyses subsequently revealed that most of the antigens identified by these screens are lipoproteins70–72 tethered by their N-terminal lipids to the cytoplasmic membrane (hence, the protein moieties are in the periplasmic space)67,73–75. However, convincing evidence now shows that the spirochete displays small amounts of lipoproteins on its surface that have the potential to enhance infectivity (Fig. 3). For example, TP0751 (also known as pallilysin) is a laminin-binding lipoprotein and zinc-dependent metalloproteinase capable of degrading clots and extracellular matrix76–78. Although expressed by T. pallidum in minute quantities, surface exposure of TP0751 has been demonstrated by knock-in experiments in Borrelia burgdorferi (the spirochete that causes Lyme borreliosis79), and the cultivatable commensal treponeme T. phagedenis80, opsonophagocytosis assays in T. pallidum77 and, most recently, protection of immunized rabbits against dissemination of spirochetes following intradermal challenge81. The X-ray structure of TP0751, demonstrating an unusual lipocalin fold, should inform efforts to clarify its multi-functionality79. Additionally, the lipoprotein Tpp17 (also known as TP0435) has been shown to be at least partially surface-exposed and can function as a cytadhesin82. The structurally characterized lipoprotein TP0453 attaches to the inner leaflet of the outer membrane via its N-terminal lipids and two amphipathic helices within its protein moiety83.

Figure 3. Molecular architecture of the cell envelope of Treponema pallidum.

Shown in the outer membrane are TP0751 (as known as pallilysin)79,81 and Tpp17 (also known as TP0435)82,241 — two surface-exposed lipoproteins; TP0453, a lipoprotein attached to the inner leaflet of the outer membrane83; BamA (also known as TP0326)84,94; a full-length T. pallidum repeat (Tpr) attached by its N-terminal portion to the peptidoglycan93,94; and a generic β-barrel that represents other non-Tpr outer-membrane proteins identified by computational mining of the T. pallidum genome112. Substrates and nutrients present in high concentration in the extracellular milieu (such as, glucose) traverse the outer membrane through porins, such as TprC. At the cytoplasmic membrane, prototypic ABC-like transporters (such as RfuABCD, a riboflavin transporter) use a periplasmic substrate-binding protein (SBP), usually lipoproteins, and components with transmembrane and ATP-binding domains to bind nutrients that have traversed the outer membrane for transport across the cytoplasmic membrane. The energy coupling factor (ECF)-type ABC transporters use a transmembrane ligand-binding protein in place of a separate periplasmic SBP for binding of ligands (BioMNY is thought to transport biotin)242. Symporter permeases (for example, TP0265) use the chemiosmotic or electrochemical gradient across the cytoplasmic membrane to drive substrate transport243. The tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP)-type transporters also use transmembrane electrochemical gradients to drive substrate transport; the periplasmic component protein TatT (also known as TP0956) likely associates with the SBP TatP (also known as TP0957) that binds ligands (perhaps hydrophobic molecules, such as long chain fatty acids), uptake of which is probably is facilitated by the permease TatQ-M (also known as TP0958) 244,245. Figure adapted from Ref.63 with permission.

BamA

With the publication of the T. pallidum genome in 1998 (Ref.65), only one protein with sequence relatedness to an outer membrane protein of Gram-negative bacteria was identified: TP0326 (also known as β-barrel assembly machinery A; BamA)84,85. BamA has a dual domain architecture consisting of a 16-stranded, outer membrane-inserted, C-terminal β-barrel and five tandem polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) repeats within the periplasm84,85. The opening of the channel is covered by a ‘dome’ comprising three extracellular loops, one of which contains an opsonic target that is sequence variable among T. pallidum strains85. BamA is the essential central component of the molecular machine that catalyses insertion of newly exported outer membrane proteins to the outer membrane86.

Tpr proteins

The T. pallidum repeat (Tpr) proteins, a 12-member paralogous family with sequence homology to the major outer sheath protein of the oral commensal T. denticola, were also identified by the T. pallidum genomic sequence65. Of these, TprK (TP0897) has received the greatest attention because of its presumed role in immune evasion by the spirochete87,88; it has been shown to undergo antigenic variation in seven regions believed to be extracellular loops harbouring B-cell epitopes89–92. DNA sequence cassettes that correspond to V-region sequences in an area of the T. pallidum chromosome located away from the tprK gene have been proposed to serve as unidirectional donor sites for the generation of variable regions by nonreciprocal gene conversion89. Two other Tpr proteins, TprC and TprI, have met stringent experimental criteria for rare outer membrane proteins. They form trimeric β-barrels when refolded in vitro, cause large increases in permeability upon insertion into liposomes and are surface-exposed opsonic targets in T. pallidum93,94. Unlike classic porins, for which the entire polypeptide forms a β-barrel, TprC and TprI are bipartite. As with BamA, the C-terminal domain forms the surface-exposed β-barrel, whereas the N-terminal half anchors the barrel to the peptidoglycan sacculus. These results collectively imply that Tprs serve as functional orthologs of Gram-negative porins, using variations in substrate specificities of their channel-forming β-barrels, probably along with differential expression, to import the spirochete’s nutritional requirements into the periplasmic space from blood and body fluids95,96. These proteins also furnish a topological template for efforts to understand how antibody responses to Tprs promote bacterial clearance.

Biosynthetic machinery

T. pallidum has evolved to dispense with a vast amount of the biosynthetic machinery found in other bacterial pathogens55,63–65. To compensate for its loss of biosynthetic capacity, the spirochete maintains a complex assortment of ABC transporters and symporters (totalling ~5% of its 1.14 MB circular genome) to transfer the broad spectrum of molecules essential for viability from periplasm to cytosol (Fig. 3). T. pallidum relies on an optimized conventional glycolytic pathway as its primary means for generating ATP. By dispensing with oxidative phosphorylation, the spirochete has no need for cytochromes and the iron required to synthesize them. Accordingly, the spirochete maintains a complex, yet parsimonious, assortment of ABC transporters and symporters (totalling ~5% of its 1.14 MB circular genome) to transfer essential molecules from the periplasmic space to the cytosol (Fig. 3). Whereas many pathogens have highly redundant systems for uptake of transition metals across the cytoplasmic membrane, T. pallidum accomplishes this task with just two ABC transporters (Tro, which imports zinc, manganese and iron, and Znu, which is zinc-specific). A small, but powerful arsenal of enzymes neutralize superoxides and peroxides to fend off host responses to infection. Lastly, the spirochete possesses novel and surprisingly intricate mechanisms ostensibly to redirect transcription and fine-tune metabolism in response to environmental cues and nutrient flux63.

Transmission and dissemination

Transmission of venereal syphilis occurs during sexual contact with an actively infected partner; exudate containing as few as 10 organisms can transmit disease8,68. Spirochetes directly penetrate mucous membranes or enter through abrasions in skin, which is less heavily keratinized in peri-genital and peri-anal areas than skin elsewhere8,68. To establish infection, T. pallidum must adhere to epithelial cells and extracellular matrix components; in vitro binding studies suggest that fibronectin and laminin are key substrates for these interaction76,97–99. Once below the epithelium, organisms multiply locally and begin to disseminate through the lymphatics and bloodstream. Spirochetes penetrate extracellular matrix and intercellular junctions by ‘stop and go’ movements that coordinate adherence with motility, powered by front-to-back undulating waves generated by flagellar rotation and presumably assisted by the proteolytic activity of TP0751 77,100. Ex vivo studies using cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Fig. 4A) suggest that spirochetes invade tissues using direct motility to negotiate their way through intercellular junctions, so-called inter-junctional penetration7,101. The infection rapidly becomes systemic9,16,100. Profuse spirochetes within the epidermis and superficial dermis in secondary syphilitic lesions (Fig. 4B) enable tiny abrasions created during sexual activity to transmit infection10,102. Penetration of the blood–brain barrier, occurring in as many as 40% of individuals with untreated early syphilis, can cause devastating neurological complications9,16.

Figure 4. Treponema pallidum invasion.

A | Transmission electron micrograph of T. pallidum (arrowheads) penetrating the junctions between cultured umbilical vein endothelial cells. ‘Inter-junctional invasion’ following attachment to vascular endothelium is thought to provide T. pallidum access to tissue parenchyma during haematogenous dissemination. Reprinted with permission from Reference101. B | Immunohistochemical staining (using commercial anti-T. pallidum antibodies) of a secondary syphilis skin lesion reveals abundant spirochetes embedded within a mixed cellular inflammatory infiltrate in the papillary dermis. The inflammatory response elicited by spirochetes replicating in tissues is widely thought to be the cause of clinical manifestations in all stages of syphilis. Reprinted with permission from10. C | Human syphilitic serum (HSS) dramatically enhances opsonophagocytosis of T. pallidum by purified human peripheral blood monocytes compared with D | normal human serum (NHS). Arrowheads indicate treponemes being degraded within phagolysosomes.

Adaptive immune response and inflammation

Although the paucity of PAMPs in the T. pallidum outer membrane enables the bacterium to replicate locally and undergo repeated bouts of dissemination, pathogen sensing in the host is eventually triggered. The organisms are taken up by dendritic cells103, which then traffic to draining lymph nodes to present cognate treponemal antigens to naive B cells and T cells. The production of opsonic antibodies markedly enhances the uptake and degradation of spirochetes by phagocytes (Fig. 4C,D), liberating lipopeptides and other PAMPs for binding to Toll-like receptors lining the interior of the phagosome and antigenic peptides for presentation to locally recruited T cells62,104,105. Activated lesional T cells secrete IFN-γ, promoting clearance by macrophages, but also bolstering the production of tissue-damaging cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6 10,106,107. Immunohistochemical analysis has identified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells10,106,108,109, natural killer cells10 and activated macrophages in early syphilis lesions10,109. Perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes, histiocytes (phagocytic cells in connective tissues) and plasma cells with endothelial cell swelling and proliferation are characteristic histopathological findings in all stages of syphilis and can progress to frank endarteritis obliterans (leading to occlusion of arteries and severe clinical manifestations, such as the stroke syndromes of meningovascular syphilis)9,110.

Antibody avoidance

T. pallidum is widely regarded as an extracellular bacterium61. Thus, a question of paramount importance is why, unlike ‘classic’ extracellular pathogens, syphilis spirochetes not only fail to be cleared rapidly but can replicate and circulate in the midst of a prolific antibody response8,68,69. Immunolabelling, opsonophagocytosis, and complement-dependent neutralization assays have shown that T. pallidum populations consist of antibody-binding and non-binding subpopulations; the minority of organisms that bind antibodies do so in minute amounts and with delayed kinetics10,111–114. Accordingly, one can envision a scenario whereby nonbinders replenish the spirochetes that bind and are cleared63.

Understanding the basis for the heterogeneity of T. pallidum’s surface antigenicity is critical to unravelling its strategy for antibody avoidance. The picture emerging from our evolving concepts of the spirochete’s molecular architecture is multi-factorial and likely involves copious production of antibodies against subsurface lipoprotein ‘decoys’57,110; poor target availability owing to low copy numbers of outer membrane proteins and surface-exposed lipoproteins67,77,82,84,93; in the case of bipartite outer membrane proteins, limited production of antibodies against surface-exposed epitopes along with skewed production of antibodies against periplasmic domain84,93; organism-to-organism variation in the levels of expression of outer membrane proteins and outer surface lipoproteins through a variety of mechanisms, including phase variation82,92,115,116; and, in the case of TprK, antigenic variation as a result of intra-genomic recombination89,92,117. Additionally, the ability of motile spirochetes to ‘outrun’ infiltrating phagocytes and reach sequestered locations, including the epidermis, could be an under-appreciated aspect of immune evasion10,102. As infection proceeds, the antibody repertoire possibly broadens and intensifies to the point where the antigen-poor surface of the spirochete is overwhelmed and its capacity for antigenic variation is exhausted, ushering in the asymptomatic period called latency. Once in the latent state, the organism can survive for years in untreated individuals, establishing niduses of inflammation in skin, bones, the thoracic aorta, the posterior uveal tract and the central nervous system, that set the stage for recrudescent disease — collectively referred to as tertiary syphilis. How immune containment mechanisms decline and enable the balance to shift back in favour of the pathogen in tertiary syphilis is inclear9, although a hyper-intense cellular response to the spirochete is generally believed to be the cause of the highly destructive lesions of tertiary syphilis9. Numerous case reports and small series suggest that HIV infection predisposes to neuro-ophthalmological complications in those with syphilis16. Cardiovascular syphilis, typically involving the aortic arch and leading to aneurysmal dilatation, usually occurs 10–30 years after the initial infection9.

Congenital infection

Although MTCT of syphilis can occur at the time of delivery, the overwhelming majority of cases are caused by to in utero transmission. Studies have shown spirochetes in placenta and umbilical cord samples, supporting transplacental passage of the organism to the fetus, as early as 9–10 weeks of gestation118. Although fetal syphilis infection was not thought to occur prior to the second trimester, the fetus can indeed be infected very early in pregnancy but may be unable to mount a characteristic immune response until development of the embryonic immune system at 18–20 weeks gestation.

Transmission risk is directly related to stage of syphilis in the pregnant woman (that is, the extent and duration of fetal exposure to spirochetes). Small case series have found highest MTCT risk in primary and secondary stages, during which transmission probability may be ≥80%. In latent (asymptomatic) infections during pregnancy, probability of transmission to the fetus is highest during the first 4 years after infection, after which risk declines18,45. Systematic reviews assessing women with predominantly asymptomatic infections are consistent in showing that delayed or lack of adequate treatment results in stillbirth, early neonatal death, prematurity, low birth weight or congenital infection in infants (more than half of syphilis-exposed pregnancies); syphilitic stillbirth was the most commonly observed adverse outcomes in syphilis-exposed pregnancies21,45,119.

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Syphilis has varied and often subtle manifestations that make clinical diagnosis difficult and lead to many infections being unrecognized. The classically painless lesions of primary syphilis can be missed, especially in hidden sites of exposure such as the cervix or rectum. The rash (Fig. 5) and other symptoms of secondary syphilis can be faint or mistaken for other conditions. A syphilis diagnosis is often based on a suggestive clinical history and supportive laboratory9,16 (that is, serodiagnostic) tests. Serological testing has become the most common means to diagnose syphilis whether in people with symptoms of syphilis, or in those who have no symptoms but are detected through screening. A limitation of all syphilis serological tests is their inability to distinguish between infection with T. pallidum subsp. pallidum and the non-venereal T. pallidum subspecies that cause yaws, pinta or bejel.

Figure 5. Clinical presentation of primary, secondary and congenital syphilis.

A | Primary chancre. B | Primary chancre with rash of secondary syphilis. C | Secondary syphilis in a pregnant woman, who has palmar rash. D | Secondary syphilis as palmar rash. E | 3-month old baby with congenital syphilis, showing hepatosplenomegaly and desquamating rash. The child also presented with nasal discharge. F | Typical palmar desquamating rash in baby with congenital syphilis.

Ensuring accuracy and reliability of syphilis testing is important, especially in nonspecialized laboratories where most patients are tested120. Syphilis-specific quality assurance strategies include training of technologists on specific techniques, internal quality control systems; test evaluation; and interassay standardization of commercially available test kits on a regular basis37,120. It is especially important to provide adequate training and regular external quality assessment or proficiency testing with corrective action to ensure the quality of tests and testing for health care providers who perform rapid tests in clinic based or outreach settings121–124. Because many parts of the world lack laboratory capacity for accurate diagnosis, the requirement for laboratory testing has greatly constrained syphilis control and congenital syphilis elimination. However, development of inexpensive rapid tests that can be performed at the POC has greatly increased access to prenatal screening and diagnosis, even in low-resourced and remote settings.

Definitive diagnosis by direct detection

The choice of method for diagnosing syphilis depends on the stage of disease and the clinical presentation125. In patients presenting with primary syphilitic ulcers, condyloma lata (genital lesions of secondary syphilis) or lesions of congenital syphilis, direct detection methods — which include darkfield microscopy, fluorescent antibody staining, immunohistochemistry and PCR — may be used to make a microbiological diagnosis. However, with the exception of PCR, these methods are insensitive and require fresh lesions from which swab or biopsy material can be collected as well as well-experienced technologists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Direct detection methods for Treponema pallidum

| Method | Sample | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Darkfield microscopy | Fresh (<20 minutes) sample from chancres or erosive cutaneous lesions of primary, secondary or congenital syphilis |

|

|

| Direct fluorescent antibody staining for T. pallidum | Sample from chancres or erosive cutaneous lesions of primary, secondary or congenital syphilis |

|

|

| Immunohistochemistry | Skin, mucosal or tissue lesions performed on fixed paraffin embedded tissues using commercially available treponemal antibody reagents |

|

|

| PCR | Skin, mucosal or tissue lesions; not recommended for blood or CSF as few organisms present |

|

|

Microscopy had been used for direct detection and diagnosis since 1920, but is now used infrequently. A 2014 survey of national reference and large clinical laboratories in Latin America and the Caribbean found that only two of 69 participating facilities, of which half were reference laboratories, still performed darkfield or direct fluorescent antibody staining for T. pallidum (DFA-TP)126. The most recent European guidelines recommended against DFA-TP testing in clinical settings, and the reagents are no longer available13. PCR techniques are increasingly used; however, there is as yet no commercially available or internationally approved test for T. pallidum13. Species-specific and subspecies-specific T. pallidum PCR testing is a developing technology that is still primarily available in research laboratories127,128, although these tests are anticipated to be more widely available in the near future. A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that T. pallidum PCR was more efficient for confirmation than to exclude syphilis diagnosis in lesions129. Recent research indicates that this technology may be helpful for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis by the detection of T. pallidum DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with syphilis, particularly among HIV-infected individuals130,131.

Diagnosis using serology

Serodiagnostic tests are the only means for screening asymptomatic individuals and are the most commonly used methods to diagnose patients presenting with signs and symptoms suggestive of syphilis. Serodiagnostic tests for syphilis can be broadly categorized into non-treponemal tests (NTTs) and treponemal tests (TTs).

NTTs

NTTs measure immunoglobulins (IgM and IgG) produced in response to lipoidal material released from the bacterium and/or dying host cells. The most commonly used NTTs — the Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) test, the Toluidine Red Unheated Serum Test (TRUST) and the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test — are flocculation (precipitation) tests that detect antibodies to a suspension of lecithin (including phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine), cholesterol and cardiolipin. NTTs are useful in detecting active syphilis. However, because they do not become positive until 10–15 days after onset of the primary lesion, 25–30% of primary syphilis cases may be missed (Fig. 6)132,133. Although relatively simple and inexpensive, NTTs must be performed manually on serum, and rely on subjective interpretation (Table 2). These tests also require trained laboratory personnel and specialized reagents and equipment and, therefore, do not fulfil the ASSURED (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, equipment-free and Deliverable to those who need them) criteria for tests that can be used at the point of care 134.

Figure 6. Serological response to primary and secondary syphilis.

Diagnosis of syphilis can be made by measuring a patient’s serological response to infection. IgM antibodies against Treponema pallidum proteins are the first to appear, followed a few weeks later by IgG antibodies. Both IgM and IgG antibodies can be measured using treponemal tests such as the T. pallidum Haemagglutination Assay (TPHA), T. pallidum Particle Assay (TPPA), Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorption assay (FTA-ABS), enzyme immunoassays (EIA) and Chemilluminescent immunoassays (CIA). IgM and IgG antibodies against proteins that are not specific to T. pallidum (non-treponemal antibodies) can be detected using the Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) or toluidine red unheated serum (TRUST) tests and usually appear 2–3 week after treponemal antibodies. With effective treatment (which is arbitrarily shown here at 6 months), the non-treponemal antibody levels decline whereas the treponemal antibodies remain high for many years. In ~20% of patients, non-trepnemal antibodies persist 6 months after treatment; these individuals are labelled as having a serofast status. Despite repeated treatment, ~11% of patients remain serofast187. Here, we show early syphilis (including primary, secondary and early latent infections; infectious syphilis) and late syphilis (including late latent and tertiary infections) as being ≤1 year in duration and >1 year in duration, respectively, in line with US and European guidelines. However, the WHO guidelines place this demarcation at 2 years. Beyond primary and secondary syphilis, the pattern of serological response over time is less well defined and is accordingly not shown.

Table 2.

Serological tests for Treponema pallidum

| Method | Sample | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nontreponemal tests (NTTs) | |||

| Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) slide test | Serum, plasma or CSF |

|

|

| Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) or Toluidine Unheated Serum Test (TRUST) | Serum or plasma |

|

|

| Treponemal tests (TTs) | |||

| Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorbed (FTA-ABS) test | Serum or plasma, CSF |

|

|

| T. pallidum Particle Agglutination (TPPA) | Serum or plasma |

|

|

| T. pallidum Haemagglutination (TPHA) and micro-haemagglutination assay (MHA-Tp) | Serum or plasma |

|

|

| Treponemal Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) | Serum |

|

|

| Chemiluminescence Immunoassay (CIA) | Serum |

|

|

| Rapid tests | |||

| Treponemal | Whole blood, plasma or serum |

|

|

| Treponemal/nontreponemal test | Whole blood, plasma or serum |

|

|

| Dual syphilis/HIV tests | Whole blood, plasma or serum |

|

|

The data on sensitivity and specificity of each test with respect to disease stage are reported in the WHO Manual on Laboratory Diagnosis of Sexually Transmitted Infections, including HIV 252.

Without treatment, titres peak at 1–2 years after infection and remain positive even in late disease (usually at a low titre). After treatment, titres generally decline and in most immunocompetent individuals become nonreactive within 6 months. However, up to 20% of syphilis-infected individuals have a persistently reactive (albeit low-titre) NTT even after treatment, possibly related to a less robust pro-inflammatory immune response135. These patients are labelled as having a serofast status and are observed more commonly with treatment for late latent than early syphilis37,136. Biologic false positive results can occur in ~2–5% of the population, regardless of the NTT test used— although the proportion is difficult to estimate with certainty because it is influenced by the population studied137. These low-titre reactions might be of limited duration if related to acute factors (such as febrile illness, immunization or pregnancy) or longer duration if related to chronic conditions (such as autoimmune diseases, hepatitis C infection or leprosy) 136,138. By contrast, false-negative results can occur in sera with very high titres (such as those with secondary syphilis) that are not diluted before testing, a phenomenon known as a Prozone effect. Pre-dilution of sera re-establishes the concentration needed for optimal antibody–antigen interaction and avoids this problem.

TTs

In contrast to NTTs, TTs detect antibodies directed against T. pallidum proteins and are theoretically highly specific. However, as most syphilis-infected individuals develop treponemal antibodies that persist throughout life, TTs cannot be used to distinguish an active from a past or previously treated infection and are not useful in evaluating treatment efficacy. TTs are used as confirmatory assays following a positive NTT result.

TTs become positive 6–14 days after the primary chancre appears (~5 weeks after infection) and, therefore, may be useful to detect early syphilis missed by NTT testing. These tests are usually laboratory based and include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS) test, the microhaemagglutination assay for antibodies to T. pallidum (MHA-TP), the T. pallidum passive particle agglutination (TPPA) and T. pallidum haemagglutination (TPHA) assays (Table 2). These tests also require trained personnel in a laboratory setting, are more expensive and technically more complex than NTTs and involve specialized reagents and equipment. For these reasons, in the developing world, laboratory-based TTs are not widely available in primary care settings, hence limiting their utility as confirmatory assays for NTTs.

In recent years, TTs using recombinant T. pallidum antigens in enzyme and chemiluminescence immunoassay (EIA and CIA, respectively) formats have been commercialized. These assays are useful for large-scale screening as they are automated or semi-automated and, because they are read spectrophotometrically, are not subjective13,139–142. In higher income countries, many health care institutions depend upon high throughput screening and have adopted ‘reverse’ algorithms that screen with an automated treponemal EIA or CIA and confirm with a NTT rather than the opposite, traditional approach (Fig. 7). Few studies as yet have addressed the accuracy of these ‘reverse testing’ algorithms 40,143. The traditional and reverse approaches should theoretically produce the same result. However, the reverse alogorithm results in the detection of early syphilis cases (TT-positive, NTT-negative) that would not detected by the conventional approach144. As this pattern of serological reactivity occurs in very early primary syphilis, in previously treated disease and late infection, considerable attention should be given to a thorough physical examination of the patient, previous history and recent sexual risk before initiating any treatment and partner notification activities.

Figure 7. Screening algorithms for syphilis.

A | The traditional algorithm begins with a qualitative non-treponemal test (NTT) that is confirmed with a treponemal test (TT). This algorithm has a high positive predictive value when both tests are reactive, although early primary and previously treated infections can be missed owing to the lower sensitivity of NTTs136. Importantly, this algorithm is less costly than reverse screening algorithms, and does not require highly specialized laboratory equipment, but is limited by subjective interpretation of the technologist. Additionally, false negative NTT results can arise from the prozone effect (when there is an excess of antibody). Finally, because the traditional algorithm is not always followed by a confirmatory TT, previously treated, early untreated and late latent cases can be missed and biologically false-positive cases can be overtreated. B | The reverse screening algorithm uses a TT with recombinant T. pallidum antigens in enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or chemiluminescence immunoassay (CIA) formats that, when reactive, is followed by an NTT. This approach is associated with higher initial setup costs and ongoing operational costs than the traditional algorithm, but the algorithm permits treatment of 99% of syphilis cases, compared to the traditional algorithm in a low-prevalence setting246. Also, because TTs are not flocculation assays, false negative tests due to the Prozone effect do not occur. However, in high-risk populations, screening with a TT can result in a high rate of positive results due to previously treated infections, leading to increased clinician workload needed to review cases and determine appropriate management. Some guidelines recommend further evaluation of reactive TT with a quantitative NTT and, if results of the latter are nonreactive, a second (different) TT to help resolve the discordant results143,247,248. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control uses a variation of this approach: a reactive TT immunoassay is followed by a second (different) TT of any kind (that is, not followed by an NTT)249. Ideally, a positive TT should be supplemented by another TT or an NTT. However, in most developing countries, and in particular given the serious consequences of syphilis in pregnancy, treatment is recommended in a patient with a positive TT result.

Rapid tests

POC rapid TTs are a recent technology that enable onsite screening and treatment, and are particularly useful in settings with limited laboratory capacity. Rapid syphilis use a finger-prick whole blood sample and are are typically immuno-chromatographic strip-based TT assays that can be stored at room temperature, require no equipment and minimal training, and give a result in <20 minutes145 (Table 2). Various rapid tests have been evaluated in a range of clinical and community settings and shown to fulfil the ASSURED criteria134,146–154. Like other TTs, most POC diagnostics have the limitation of being unable to distinguish between recent and previously treated syphilis infection and, therefore, could lead to overtreatment. Ideally, patients found to have a reactive POC TT would be further evaluated with an NTT to support management decisions; however, this is often not possible in settings with limited laboratory capacity as is the case in many antenatal care clinics and outreach programmes for high-risk populations. POC rapid tests play an important part when delayed diagnosis is problematic, such as in pregnant women in whom delayed or no treatment poses significant risks to the fetus that far outweigh the risks of overtreatment for the mother45,155. In non-pregnant individuals, treatment is recommended in those who test positive if they have no prior history of treatment, and to refer those with a prior history to have an NTT11.

At least one test has been developed that enables simultaneous detection of non-treponemal and treponemal antibodies in a single POC device156–158. Additionally, dual syphilis/HIV rapid tests are available to screen for HIV and treponemal antibodies using a single lateral flow immunochromatographic strip. These are an increasingly important tool in the global elimination of MTCT of HIV and syphilis in settings in which laboratory capacity is limited159.

Tests useful in special situations

Neurosyphilis

The diagnosis of neurosyphilis is challenging. The CSF is frequently abnormal in patients with neurosyphilis with both pleocytosis (lymphocyte accumulation) and a raised protein concentration. The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) assay performed on CSF is considered the gold standard for specificity but is recognized to have limited sensitivity160,161. Other CSF tests, including serological assays — such as the Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR)162, FTA-ABS163 and TPHA164 — and molecular assays including PCR165 have all been assessed for CSF and have variable specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Difficulties in interpretation of CSF pleocytosis in individuals co-infected with HIV and syphilis challenge the evaluation of the relationship between the two diseases. CSF pleocytosis occurs in individuals with either infection alone37,165; thus, discerning the cause of pleocytosis in co-infected individuals is not always possible.

Congenital syphilis

Diagnosis of congenital syphilis in exposed, asymptomatic infants is another area in testing can be improved. Because maternal nontreponemal and treponemal IgG antibodies can be transferred from mother to child, treponemal testing of infant serum is difficult to interpret and is not recommended37. An infant with a reactive RPR or VDRL serum titre that is ≥4-times than those of the mother is highly suggestive of congenital syphilis, but its absence does not exclude the diagnosis. A clinical examination, reactive infant CSF VDRL, abnormal complete blood count or liver function tests or suggestive long-bone radiographs (that, for example, show retarded ossification or dislocation of epiphyses and radiolucencies, especially of long bones) can support a diagnosis of congenital syphilis. Use of IgM immunoblots is controversial owing to limited availability of tests and inconclusive data thus far on sensitivity; their use in diagnosing congenital syphilis is recommended in some guidelines11,13 but not others37. Maternal syphilis infection is highly correlated with fetal loss, therefore, evaluation of a stillborn infant should include evaluation of maternal tests for syphilis11.

Screening

The wide availability of effective treatment and resulting decline in syphilis prevalence has led to low yield of screening in low prevalence settings; thus, screening in low-risk adults (for example, premarital adults or those admitted to hospital) has been abandoned in most places. However, systematic reviews provide convincing evidence in favour of syphilis screening in pregnant women13,166, adults and adolescents at increased risk for infection13,40 and individuals donating blood, blood products or solid organs 13,167–169. Several countries also recommend syphilis testing in people with unexplained sudden visual loss, deafness or meningitis as these may be manifestations of early neurosyphilis13,37.

Prenatal screening

Syphilis screening is universally recommended for pregnant women, regardless of previous exposure, because of the high risk of MTCT during pregnancy and the availability of a highly effective preventive intervention against adverse pregnancy outcomes11,37,41,46. Global normative authorities and most national guidelines recommend syphilis screening at the first prenatal visit, ideally during the first trimester11,37,41,170. Some countries recommend that women at high risk have repeat screening in the third trimester and again at delivery to identify new infections37. Women should be tested in each pregnancy, even if they have tested negatively in a previous pregnancy. When access to prenatal care is not optimal or laboratory capacity is limited, rapid tests have been found beneficial in detecting and treating syphilis in pregnancy148. Guidelines recommend that, post-delivery, neonates should not be discharged from the health facility unless the serological status of the mother had been determined at least once during pregnancy and preferably again at delivery11,37.

The importance of universal syphilis screening in pregnancy to prevent perinatal and infant morbidity and mortality is highlighted in the current WHO global initiative to eliminate congenital syphilis43,44 and justified by the continuing high global burden of congenital syphilis, availability of an effective and affordable preventive intervention and wider availability of low cost POC rapid tests that can be used when laboratory capacity is lacking23,43,44,46,145. A systematic review of studies (most of which were conducted in low-income countries) reporting on antenatal programmes initiating or expanding syphilis screening, compared with various local control conditions, found that enhanced screening reduced syphilis-associated adverse birth outcomes by >50% 171. Integration of syphilis testing with other prenatal interventions, including HIV testing, has been shown to be cost-effective across settings, even when syphilis prevalence is low48–51. Strategies that enhance screening coverage, such as increased use of POC rapid testing and integrating syphilis and HIV screening, will further support global elimination of congenital syphilis145,172–174.

Screening at-risk populations

Increased risk for infection can be related to personal or partner behaviours leading to syphilis infection or living in a community with high syphilis prevalence37,40. In many countries, syphilis testing is recommended for all attendees at STI or sexual health centres and as part of integrated services targeted to high-risk groups (such as HIV testing centres or drug treatment centres)13,37. The optimal screening interval for individuals at increased risk for infection is not well established; however, some guidelines suggest that MSM or people with HIV may benefit from more frequent screening than others at risk for syphilis (for example, 3 monthly rather than annual screening) 37,40,175,176.

At-risk communities are often marginalized from care and experience discrimination and stigma when using traditional STI services177. Innovations in promoting uptake of testing and developing user-friendly services are important in the control of syphilis in these communities to reduce transmission. Social entrepreneurship and crowdsourcing approaches have been shown as innovative approaches to improve HIV and syphilis testing coverage rates and accelerate linkage to care, two fundamental elements within the cascade of STI service delivery178,179. Evaluation studies of other interventions, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for syphilis, are also underway180. One option in the future might be to simultaneously administer PrEP for syphilis and HIV181.

Blood bank screening

Although syphilis was among the first identified infectious risks for blood donation and s transmission through blood has been documented182–184, reports of transfusion-transmitted syphilis have become exceedingly rare over the past 60 years as increasingly more countries adopt donor selection processes, universal serological screening of donors and use of refrigerated products rather than fresh blood components183,185. Survival of T. pallidum in different blood components has been shown to vary according to storage conditions, with fresh blood or blood components stored for <5 days more infectious than blood stored for longer periods183. Syphilis screening of blood, blood components or solid organs remains a recommendation in many countries13,169. Occasional cases of transfusion-transmitted syphilis are still reported in settings with high syphilis prevalence, particularly with transfusion of fresh blood167.

Prevention

There is as yet no vaccine against syphilis, and the most effective mode of prevention is prompt treatment to avoid continued transmission of the disease sexually or vertically from mother-to-child, and treatment of all sex partners to avoid reinfection. Other prevention modalities against venereal transmission of syphilis are latex condom use, male circumcision and avoiding sex with infected partners37. Treatment of exposed sex partners is important to avoid reinfection37.

Management

Important factors in managing syphilis are early detection, prompt treatment with an effective antibiotic regimen and treatment of sex partners of a person with infectious syphilis (primary, secondary or early latent infections). The WHO guidelines11 (Box 1) and European guidelines13 for the management of early syphilis in adults are the same. The CDC guidelines do not offer procaine penicillin as a treatment, but are otherwise identical12. Patients with late syphilis are no longer infectious. Thus, the objective of treatment is to prevent complications in persons who are asymptomatic (that is, have late latent syphilis) or arrest their development if the patient has manifestations of tertiary disease. Treatment of late syphilis requires longer courses of antimicrobial therapy than early disease.

Box 1. WHO guidelines for the treatment of syphilis.

Early syphilis

Intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (single dose)

Or intramuscular procaine penicillin (daily doses for 10–14 days)

If penicillin-based treatment cannot be used, oral doxycycline (twice daily doses for 10–14 days)* or intramuscular ceftriaxone (daily doses for 10–14 days)

Late syphilis

Intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (weekly doses for 3 weeks)

Or intramuscular procaine penicillin (daily doses for 20 days)

If penicillin-based treatment cannot be used, oral doxycycline (daily doses for 30 days)*

Congenital syphilis

Intravenous aqueous benzyl penicillin six hourly (for 10–15 days)

Or intramuscular procaine penicillin daily (for 10–15 days)

*Contraindicated in pregnancy. From Ref.11

Penicillin

Penicillin has been the mainstay of treatment for syphilis since it first became widely available in the late 1940s. Although its efficacy was never demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial, it was clearly far superior to all previous treatments, and T. pallidum resistance to penicillin has never been reported. As T. pallidum divides slower than most bacteria, it is necessary to maintain penicillin levels in the blood above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for at least 10 days; this can be achieved by giving a single intramuscular injection of long-acting benzathine penicillin G (which benefits from not requiring patient adherence to a prolonged drug regimen). The first-line treatments for early syphilis recommended by the CDC and European (authored by the International Union Against Sexually Transmitted Infections) guidelines are very similar12,13 as are recommendations for treatment of exposed sex partners. Patients with late syphilis, or with syphilis of unknown duration, should receive longer courses of treatment (Box 1). Those with symptoms suggestive of neurosyphilis or ocular involvement should undergo lumbar puncture to confirm or rule out the presence of neurosyphilis, which requires more intensive treatment. However, CDC and European guidelines define latent syphilis as occurring beginning at 1 year after infection, whereas the WHO defines latent syphilis to occur beginning at 2 years, resulting in some differences in management; that is, longer treatment duration is required for some patients in the United States and Europe.

Given that confirmation or exclusion of the presence of viable T. pallidum after treatment is not possible, treatment efficacy is measured indirectly using serology. Cure is usually defined as reversion to negative or a fourfold reduction in titre of an NTT. However, as noted earlier, a minority of patients remain seropositive, with a less than four-fold reduction in NTT titre, in spite of almost certainly having been cured and with no evidence of progressive disease — the so-called serofast state186. The management of these patients depends on taking a careful sexual history to exclude the possibility of reinfection, which can be challenging as patients may not recognize new infections. The serofast state more commonly occurs in patients with late syphilis and low NTT titres and in HIV-positive patients who are not on anti-retroviral treatment187. Because few data are available on long-term clinical outcomes in serofast patients, CDC guidelines recommend continuing clinical follow up and retreatment if follow up cannot be ensured12.

Second-line treatments

Patients who are allergic to penicillin should be treated with doxycycline or ceftriaxone (though allergy to cephalosporins is more common in those who are allergic to penicillin) with repeat NTT serology as follow up. Doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnancy. Two treatment trials of early syphilis in Africa showed that a single oral dose of azithromycin was equivalent to benzathine penicillin G188,189. Unfortunately, strains of T. pallidum with a mutation that confers resistance to azithromycin and other macrolide antibiotics are common in the United States, Europe, China and Australia190–194. A study in HIV-positive patients with syphilis showed that azithromycin to prevent opportunistic infections led to better serological outcomes195. The WHO recommends the use of azithromycin for the treatment of syphilis only in settings where the prevalence of macrolide-resistant T. pallidum is known to be very low.

HIV co-infection

In patients with early syphilis, a raised CSF cell count and protein are found more frequently in the CSF of patients with HIV infection than in HIV-uninfected patients, and there is some evidence that early symptomatic neurosyphilis is more common in HIV-positive patients196,197. As single-dose benzathine penicillin G does not reliably lead to treponemicidal levels in the CSF, some experts have suggested that HIV co-infected patients with early syphilis should receive enhanced treatment 198. However, a randomized controlled trial (n= 541) showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes between patients receiving standard or enhanced treatment15. Notably, the 101 HIV-infected patients enrolled in the trial responded less well serologically, but due to loss to follow up the study was underpowered to detect a two-fold difference in standard versus enhanced treatment in HIV co-infected patients. Furthermore, a large (n=573) prospective observational study in Taiwan found no difference between single-dose benzathine penicillin G and enhanced treatment in a per-protocol analysis199. However, using a last-observed-carried-forward analysis to account for missing data, the authors concluded that 67.1% of those who received one dose responded serologically compared with 74.8%who received the enhanced treatment, a statistically significant difference (P=0.044) 199. Finally, a retrospective study (n= 478) showed no difference in serological response at 13 months between those receiving single-dose benzathine penicillin G and enhanced treatment 200. Given the inconclusive results of these studies, many clinicians continue to offer enhanced therapy to HIV co-infected patients with early syphilis.

Treatment in pregnancy

Adverse pregnancy outcomes are common in women with syphilis45,119. A study in Tanzania found that, of women with latent syphilis who had RPR titres ≥1:8, 25% delivered a stillborn, and 33% a live but preterm infant21. A second study showed that adverse pregnancy outcomes due to syphilis can be prevented with a single dose of benzathine penicillin G given before 28 weeks’ gestation201 and that, in this setting, in which 5–6% of pregnant women had syphilis, this was one of the most cost-effective interventions available in terms of cost per disability-adjusted life year saved202.

Penicillin is the only antibiotic known to be effective in treating syphilis in pregnancy and preventing adverse birth outcomes. Since doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnancy, and macrolides such as azithromycin and erythromycin do not cross the placenta well, there are few alternatives to penicillin for the treatment of pregnant women with syphilis who are allergic to penicillin. The CDC recommends desensitization for those who are allergic to penicillin12.

Congenital syphilis

The WHO recommends that infants with suspected congenital syphilis, including infants who are born to syphilis-seropositive mothers who were not treated with penicillin >30 days before delivery, should be treated with aqueous benzyl penicillin or procaine penicillin (Box 1). All syphilis-exposed infants, including infants without signs or symptoms at birth, should be followed closely, ideally with NTT titres. Titres should decline by 3 months of age and be nonreactive by 6 months12. TTs are not useful in infants due to persistent maternal antibody.

Neurosyphilis and ocular syphilis

CNS involvement can occur during any stage of syphilis, but there is no evidence supporting a need to deviate from recommended syphilis regimens without presence of clinical neurological findings (such as ophthalmical or auditory symptoms, cranial nerve palsies, cognitive dysfunction, motor or sensory deficits, or signs of meningitis or stroke)203. With symptoms and tests indicating neurosyphilis, or any suggestion of ocular syphilis regardless of CSF testing, more-intensive treatment is recommended. For example, the CDC recommends that adults with neurosyphilis or ocular syphilis should be treated with high-dose intravenous aqueous crystalline, or intramuscular procaine penicillin plus probenecid, for 10–14 days204.

Quality of life

Historical reports dating from the 15th century indicate that syphilis was perceived as a dangerous infection, and a source of public alarm via fear of contagion and dread of its manifestations and anxiety around its highly toxic ‘cures’ (heavy metal therapy with mercury, arsenicals or bismuth)205–207. Case reports through the 19th century as well as modern re-evaluations of skeletal remains support the fact that the disease could cause severe physical stigmata, with individuals having disfiguring rashes; non-healing ulcerations; painful bony lesions that often involved destruction of the nose and palate; visceral involvement; dementia and other incapacitating neurological complications; and early death208. Stigmatization associated with syphilis was also evident, with symptomatic patients quarantined to specialized hospitals, and affected people hiding their symptoms — perhaps fearing societal shunning or the dubiously effective treatment regimens even more than the disease209. Reductions in syphilis prevalence were documented after the introduction of penicillin210 and since that time, the most virulent manifestations of the disease have almost vanished, and today it is rare to find a patient with tertiary disease211. Nevertheless, continuing reports emphasize that complications of late syphilis, particularly those involving the eyes, CNS and cardiovascular system, can cause lifelong disability and even death9. For example, case numbers of ocular syphilis have increased with rising syphilis incidence rates in many communities212, with delayed treatment associated with permanently diminished visual acuity213. It is essential, therefore, that caregivers be cognizant of the need to screen at-risk patients for latent infection and administer therapy if previous treatment has not been documented.

Few modern studies have addressed quality of life in men and women with syphilis, whether in social, psychological or economic contexts. One study (n= 250) showed only a minor effect on patient-reported quality of life at time of treatment, and essentially no effect 1 month after treatment214. The currently high case rates of syphilis infection and reinfection among MSM in urban centres throughout the world may lend support to the notion that syphilis in the modern era poses limited impact on quality of life as long as it is detected and treated. However, partner notification studies suggest STI diagnoses can lead to significant social stigma, intense embarrassment, and fear of retaliation, domestic violence or loss of relationship177. Public health experts have posited that syphilis is the source of more stigma than other STI diagnoses, although this is difficult to measure with certainty because STI programmes tend to focus contact tracing efforts more strongly on syphilis than other curable STIs owing to its serious consequences 215. In one study measuring the level of shame associated with several stigmatizing skin diseases, patients assigned greatest shame to syphilis — more than to AIDS, other STIs or several disfiguring skin conditions216.

Untreated maternal syphilis results in severe adverse perinatal outcomes, most prominently stillbirth, in at least half of affected pregnancies45. While MTCT of syphilis is clearly linked to lack of prenatal care, WHO data indicate that globally, whether in wealthy or poor nations, most adverse pregnancy outcomes caused by maternal syphilis are in women who attended prenatal care but were not adequately tested or treated24. This suggests other factors, such as weak health systems, gender inequality, lack of political will to support quality STI and reproductive health services, or other structural influences associated with lack of screening might be at play217. An increasing literature supports that, as for infant loss, a stillbirth can lead to poor mental and other health outcomes for both parents and the wider family, even extending to health care providers. For example, experiencing a stillbirth has been linked to ‘unspoken grief’ and a variety of psychosocial consequences such as depression, blame, shame, social isolation, problems in future pregnancies and relationship dissolution218–220. In Haiti, pregnancy loss associated with syphilis (which had a maternal prevalence of 6%) is so common that a myth about a werewolf sucking the blood out of the unborn fetus has developed to help women with their loss and suffering221. Economic research suggests a stillbirth results in substantial direct and indirect costs and can sometimes require more resources than a livebirth219.

Outlook

With syphilis continuing to be the leading cause of preventable stillbirths in the developing world and re-emerging as a public health threat in developed nations, particularly in HIV co-infected MSM, the demand for improved diagnostics, prevention strategies and treatments is growing. Here, we describe the most pressing issues and propose a call to action (Box 2).

Box 2. Major challenges and a call to action wish list.

Eliminate mother-to-child transmission of syphilis

Requires political commitment

Prenatal syphilis screening to be integrated into mother-to-child elimination programmes for HIV or as a component of an essential diagnostic package for prenatal care

Develop point-of-care tests with data connectivity or data transmission capability to facilitate automated surveillance and to improve the efficiency of health systems

Address HIV and syphilis co-infection in MSM

Requires research into potential synergies between the two infections

Implement scientific and community involvement to reach at-risk populations

Integrate programmes for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis and other STIs

Develop tests for active infection, neurosyphilis and congenital syphilis

Development of biomarkers for test development

Development of network of clinical sites for rapid validation of new tests

Develop new oral drugs to prevent transmission to fetus and to sexual partners

Provide incentives for drug discovery programmes

Provide incentives to evaluate drug combinations

Develop vaccines

Requires research to better understand pathogenesis

Requires research to identify vaccine targets and methods for validation

Elimination of MTCT of syphilis

The WHO campaign to eradicate yaws, which treated >50 million people with penicillin and reduced the number of cases by at ≥95% worldwide between 1952 and 1964, was ultimately unsuccessful. What can we learn from this heroic failure? The yaws eradication campaign was based on clinical examination and serological testing to determine prevalence by community, and mass treatment or selective mass treatment (cases and contacts) of communities with penicillin, depending on prevalence. Unfortunately, as the prevalence of yaws fell, it was no longer perceived as an important public health problem worthy of an expensive vertical programme; resources were diverted to other programmes, yaws was forgotten, and it came re-emerged222. To some extent the same is true of syphilis; once penicillin became available, its incidence and prevalence declined in many parts of the world, and it was no longer seen as a public health priority. Although screening of all pregnant women for syphilis has continued to be recommended in most countries, coverage has been low in many regions; for example, WHO estimates that approximately 50% of antenatal clinic attenders in Africa are not currently screened for syphilis24. This low coverage has resulted in a high burden of entirely preventable stillbirths and neonatal deaths23. Exacerbating this situation, the WHO has received reports of stock outs and shortages of injectable benzathine penicillin G in multiple countries, many with a high burden of maternal and congenital syphilis. In collaboration with international partners, the WHO has spearheaded an initiative to assess global supply, current and projected demand, and production capacity for benzathine penicillin G223.