Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this laboratory-based study was to compare the efficacy of two hearing aid fittings, with and without non-linear frequency compression, implemented within commercially available hearing aids. Previous research regarding the utility of non-linear frequency compression has revealed conflicting results for speech recognition, marked by high individual variability. Individual differences in auditory function and cognitive abilities, specifically hearing loss slope and working memory, may contribute to aided performance. The first aim of the study was to determine the effect of non-linear frequency compression on aided speech recognition in noise and listening effort using a dual-task test paradigm. The hypothesis, based on the Ease of Language Understanding model, was that non-linear frequency compression would improve speech recognition in noise and decrease listening effort. The second aim of the study was to determine if listener variables of hearing loss slope, working memory capacity, and age, would predict performance with non-linear frequency compression.

Design

A total of 17 adults (age: 57–85) with symmetrical sensorineural hearing loss were tested in the sound field using hearing aids fit to target (NAL-NL2). Participants were recruited with a range of hearing loss severities and slopes. A within-subjects, single-blinded design was used to compare performance with and without non-linear frequency compression. Speech recognition in noise and listening effort were measured by adapting the Revised Speech in Noise Test into a dual-task paradigm. Participants were required trial-by-trial to repeat the last word of each sentence presented in speech babble and then recall the sentence-ending words after every block of six sentences. Half of the sentences were rich in context for the recognition of the final word of each sentence and half were neutral in context. Extrinsic factors of sentence context and non-linear frequency compression were manipulated, and intrinsic factors of hearing loss slope, working memory capacity, and age were measured in order to determine which participant factors were associated with benefit from non-linear frequency compression.

Results

On average, speech recognition in noise performance significantly improved with the use of non-linear frequency compression. Individuals with steeply sloping hearing loss received more recognition benefit. Recall performance also significantly improved at the group level with non-linear frequency compression revealing reduced listening effort. The older participants within the study cohort received less recall benefit than the younger participants. The benefits of non-linear frequency compression for speech recognition and listening effort did not correlate with each other, suggesting separable sources of benefit for these outcome measures.

Conclusions

Improvements of speech recognition in noise and reduced listening effort indicate that adult hearing aid users can receive benefit from non-linear frequency compression in a noisy environment, with the amount of benefit varying across individuals and across outcome measures. Evidence supports individualized selection of non-linear frequency compression, with results suggesting benefits in speech recognition for individuals with steeply sloping hearing losses and in listening effort for younger individuals. Future research is indicated with a larger data set on the dual-task paradigm as a potential cognitive outcome measure.

INTRODUCTION

Depending upon degree of high-frequency hearing loss and output limits of hearing aid receiver technology, critical high-frequency speech information is commonly not available to hearing aid users. Monson, Story, and Lotto (2014) reviewed the role of high-frequency energy (5–20 kHz) in speech and singing and discussed the importance of high-frequency energy for sound quality, localization and speech intelligibility. A number of studies have shown that difficulty perceiving high-frequency speech information can have negative consequences for speech perception (e.g., Lippmann 1996; Hogan & Turner 1998; Stelmachowicz et al. 2001; McCreery et al. 2013).

Non-linear frequency compression is a hearing aid processing strategy that is intended to restore high-frequency cues that would otherwise be unavailable to a listener with hearing loss (Simpson et al. 2005). In order to shift high-frequency spectral information from inaudible frequency regions to audible frequency regions, non-linear frequency compression algorithms use individualized compression ratios and cut-off frequencies, based upon the user’s audiogram (cf., Alexander 2013). From an acoustic point of view, individuals with steeply-sloping high-frequency hearing losses, which are often observed in an older adult population, would be predicted to receive the most benefit from this processing strategy, given that previously inaccessible high-frequency cues would be compressed into an audible frequency range (Hopkins et al. 2014). Additionally, high-frequency cues have been found to be particularly helpful for speech perception when background noise is present (Baer et al. 2002; Hornsby et al. 2011). Therefore, if non-linear frequency compression successfully restores high-frequency cues, individuals who would otherwise not have access to these cues would be predicted to benefit, particularly in noisy listening conditions.

Alexander (2013) recently provided an extensive review of frequency-lowering amplification strategies, emphasizing the individual variability in outcomes with frequency-lowering strategies. Even though non-linear frequency compression is commercially available, there remains conflicting evidence across numerous studies published over the last decade regarding its benefit for adults using a range of outcome measures in simulations or with commercial hearing aids, including consonant recognition in adults (Glista et al. 2009; McDermott & Henshall 2010; Alexander et al. 2014) and speech recognition for words and sentences (Simpson et al. 2005, 2006; Bohnert et al. 2010; Wolfe et al. 2010, 2011; McCreery et al. 2013). Several studies have investigated the use of non-linear frequency compression with a pediatric population as well, measuring its effects on phoneme discrimination, word and sentence level recognition, and subjective preferences (Glista et al. 2009; Wolfe et al. 2011; Brennan et al. 2014). Several studies published since the Alexander (2013) review have measured speech perception outcomes with non-linear frequency compression within an older adult population with hearing loss using commercially-available hearing aids.

Outcomes with Non-Linear Frequency Compression in Commercial Hearing Aids

Ellis and Munro (2015a, 2015b) published among the few studies demonstrating benefit of non-linear frequency compression for speech recognition in an adult population using commercially available hearing aids. They observed significantly improved monosyllabic word recognition in quiet and in noise as well as significantly improved sentence recognition in noise. Recognition performance was predicted most strongly by high-frequency hearing loss. However, two other recent studies demonstrated little to no benefit in a similar population using different outcome measures (Hopkins et al. 2014; Picou et al. 2015). Significant improvements for identification of the consonants /s/ and /t/ were found in quiet conditions, but no improvement for speech recognition in noise. Aside from task differences, one possible source of the variability in speech perception outcomes is the fitting algorithm used for each study to apply hearing aid gain. Studies without significant improvement for speech recognition used the NAL-NL1 prescription (Byrne et al. 2001), whereas studies with significant improvements in speech recognition made use of the NAL-NL2 prescription (Keidser et al. 2011). NAL-NL2 provides more high-frequency gain than NAL-NL1, perhaps providing greater potential benefit from non-linear frequency compression. Therefore, the high-frequency gain provided by the NAL-NL2 prescriptive hearing aid fittings as compared to NAL-NL1 would likely result in additional high-frequency cues being available after the signal is compressed.

Despite the variability in speech recognition outcomes with non-linear frequency compression, several manufacturers automatically enable non-linear frequency compression during a first-fit procedure, with the strength of the settings depending on hearing loss severity and slope. When dispensing audiologists then fit to a prescriptive target following evidence-based guidelines for practice (Valente et al. 2006), the clinical decision-making process then turns to selecting processing features that are appropriate for the needs of the individual. It is important to better understand the sources of variability in speech recognition outcomes with non-linear frequency compression in order to determine which hearing aid candidates could potentially benefit from non-linear frequency compression and in which listening environments non-linear frequency compression may be beneficial. A better understanding of which variables are driving speech perception performance with non-linear frequency compression will contribute to the evidence base for patient-centered hearing aid feature selection.

Cognitive Factors in Hearing Aid Outcomes

An emerging area of research within the field of cognitive hearing science examines how various cognitive factors in addition to hearing status influence hearing aid outcomes. The Ease of Language Understanding (ELU) model proposed by Rönnberg and colleagues (2008, 2013) highlights the significance of cognitive factors for the processing of speech in listening conditions with varying perceptual and cognitive demands. According to this model, most individuals with normal hearing sensitivity can easily process incoming speech signals rapidly and implicitly (Rapid Automatic Multimodal Binding of Phonology system). Multi-sensory information, namely from the auditory and visual peripheral networks, is combined within this system for rapid integration of incoming sensory information. However, when the speech signal is degraded either due to competing noise or hearing loss, the encoding of the speech signal may not match representations within an individual’s lexicon. Within the ELU model, when there is mismatch between an incoming speech signal and lexical representations in memory, explicit processing of the signal is assumed to become necessary to achieve speech understanding.

According to this model, explicit processing due to lexical mismatch is further hypothesized to recruit working memory, which is the ability to maintain and manipulate incoming sensory information within memory. Recruiting working memory for additional processing of a distorted speech signal is hypothesized to lead to more effortful speech perception. Since additional cognitive resources are allocated for the processing of the speech signal, there may be fewer resources that can be allocated to provide deeper encoding of the incoming message. Additionally, when context is unavailable, it is much more difficult to repair the degraded signal. Some populations, including older adults, are known to rely heavily upon context in order to determine the gist of a sentence or phrase (Pichora-Fuller et al. 1995; Pichora-Fuller 2008).

Acknowledging the potential influence that cognitive factors may have on speech perception, researchers have begun to measure not only the proportion of words or sentences that an individual can perceive and repeat (speech recognition), but also to measure the amount of listening effort that was expended for a speech perception task. Listening effort has been defined as, “The mental exertion required to attend to, and understand, an auditory message,” (McGarrigle et al. 2014, p. 434). Evidence from multiple studies demonstrates that older adults with hearing loss expend more listening effort for perceptual processing of speech stimuli than older adults with normal hearing (McCoy et al. 2005; Wingfield et al. 2005; Tun et al. 2009). The additional cognitive resources expended for perceptual processing may result in a “downstream effect” of fewer cognitive resources being available for further signal manipulation and storage into long-term memory. One measurement method with potential for clinical application in audiology is to assess listening effort using a dual-task involving memory recall of speech stimuli presented for speech recognition tasks (e.g. Smith et al. 2016). If hearing aid signal processing strategies help to reduce listening effort, then improvements in a secondary recall task can be expected. In an examination of the benefits of hearing aid signal processing, listening effort measures have been found to be sensitive to differences in the effects of signal processing even when speech recognition scores remain unchanged (Sarampalis et al. 2009; Hornsby 2013).

Sarampalis, Kalluri, Edwards, and Hafter (2009) measured listening effort with digital noise reduction processing using a dual-task test method for an adult population with hearing thresholds within normal limits. In the primary task, participants reported the final word of a sentence presented in quiet or 4-talker babble at different signal-to-noise ratios. The secondary task was to recall as many of those words as possible from blocks of eight sentences. While the noise reduction algorithm under study did not improve speech recognition, it did improve recall performance at the most difficult signal-to-noise ratio tested (−2 dB SNR). The benefit provided by the noise reduction algorithm was hypothesized to decrease the listening effort during the recognition task, possibly freeing cognitive resources within working memory for the recall task. Therefore, measures of listening effort that involve a memory task in addition to a recognition task may be more sensitive than measures of speech recognition alone to the benefit received by hearing aid users from particular processing strategies.

Interpreting the findings of Sarampalis and colleagues (2009) within the ELU framework, noise reduction processing may have helped to reduce the listening effort at the more difficult signal-to-noise ratio by improving the acoustic content of the amplified signal, thereby increasing phonological precision. The improved phonological representation of the speech signal with noise reduction would mean less explicit processing would be necessary to perceive the signal as compared to conditions without noise reduction. Another interpretation may be that the reduction of the noise level made the noise less distracting and the signal more comfortable for participants, even without direct improvements in recognition performance. Either explanation would account for a reduction in the cognitive demand for the recognition task and release cognitive resources for the secondary recall task.

Desjardins and Doherty (2014) also utilized a dual-task measure that had a primary task of sentence recognition in noise with a different secondary task (visual-tracking) to assess the benefits of noise reduction in a commercial hearing aid for listeners with hearing loss. They found that noise reduction helped reduce listening effort in the most difficult signal-to-noise ratio condition, but did not significantly improve sentence recognition in noise performance, which is consistent with the findings of Sarampalis and colleagues (2009). This finding suggests that although recognition performance did not significantly improve with the use of noise reduction, the secondary recall task was sensitive to a reduction in listening effort.

In summary, studies of cognitive factors in hearing aid outcomes support the measurement of listening effort in evaluations of hearing aid signal processing technology. In the present study, it is hypothesized that if non-linear frequency compression can successfully restore phonological cues that would otherwise be unavailable to a listener with hearing loss, then it would be likely that the improved phonological encoding would reduce the listening effort required, as measured using a recall task in addition to a recognition task. More specifically, the partial restoration of high-frequency speech acoustic cues to individuals who would otherwise not have access to them should reduce the listening effort necessary for the primary task of speech recognition, releasing cognitive resources on the secondary recall task.

Individual Differences in Hearing Aid Outcomes

The ELU model also suggests that individuals with a higher working memory capacity would be able to make better use of amplified signals provided by hearing aid processing strategies (Lunner et al. 2009; Sarampalis et al. 2009; Arehart et al. 2013; Ng et al. 2013; Souza et al. 2015a). Some hearing aid algorithms are intended to provide additional audibility to the users, but alterations of the speech signal may also be conceptualized as a form of distortion (Arehart et al., 2013; Souza et al., 2015b). Even though hearing aids do help to improve audibility for a speech signal, they also alter its spectral and temporal characteristics with the use of processing strategies such as noise reduction or non-linear frequency compression. Again, within the ELU framework, distortion introduced by hearing aid signal processing algorithms could be interpreted as inducing phonological mismatch. Individuals with higher working memory capacity would then be more likely to receive benefit from the increased audibility, while using their greater working memory capacity to resolve phonological mismatch. By contrast, individuals with lower working memory capacity may not have the cognitive resource to rapidly process the spectro-temporal alterations introduced by the signal processing strategy. Previous research has suggested that working memory capacity, often measured using the Reading Span Test (Daneman et al. 1980), may be a good predictor of benefit or detriment when using various hearing aids programmed with noise reduction, frequency lowering, and compression attack and release times (Lunner et al. 2009; Sarampalis et al. 2009; Arehart et al. 2013; Ng et al. 2013; Souza & Sirow 2014). Individuals with greater working memory capacity have tended to receive more benefit from various hearing aid processing strategies than individuals with low working memory capacity. Given that non-linear frequency compression changes the spectral representations of incoming sound, working memory capacity may influence recognition and recall of speech in noise while using this particular processing strategy.

Current Study

The purpose of the present study was to assess aided speech perception in noise and listening effort with and without non-linear frequency compression, implemented within commercially available hearing aids for older adults with hearing loss. A secondary goal of the study was to determine how working memory, slope of hearing loss, and age (intrinsic factors, c.f., Alexander 2013) contribute to individual differences in the potential benefits from non-linear frequency compression. Older adults with sensorineural hearing loss were chosen as the test population for this study since they commonly have high-frequency hearing loss, thus potentially benefitting from non-linear frequency compression. Following from the work of Sarampalis et al. (2009), a dual-task paradigm was used to measure aided benefit in recognition and recall tasks for older adults with bilateral sensorineural hearing losses. Within the framework of the ELU model, this test methodology should be an effective means to measure changes in speech recognition and recall performance. The level of sentence context was also manipulated in order to determine how context might interact with non-linear frequency compression for speech perception in noise performance. It was predicted that in difficult speech recognition in noise tasks, non-linear frequency compression would improve recognition performance by restoring high-frequency speech acoustic cues. It was also predicted that benefit from non-linear frequency compression may be more apparent when there is limited context, when listeners cannot rely on top-down processing and lexical knowledge to recognize speech. Further, if non-linear frequency compression improves the phonological representation of the acoustic signal, thereby reducing listening effort, then performance on the memory recall task should also improve.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

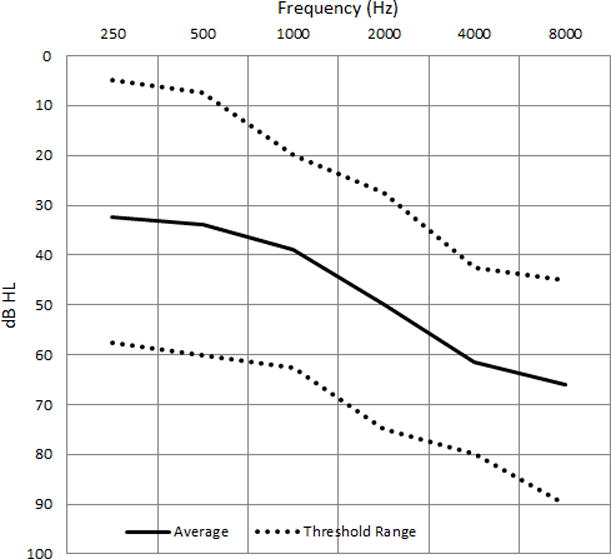

Seventeen adults with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss were recruited from the University of Arizona Hearing Clinic via flyers, letters, and word-of-mouth. The average participant age was 72 years (range: 57–85 years, SD: 7.6 years). All of the participants had symmetrical hearing thresholds (≤15 dB difference between test ears at any frequency between 250 to 6000 Hz) no worse than 90 dB HL between 250 to 6000 Hz. Four-frequency pure tone averages (0.5, 1, 2, & 4 kHz) ranged between mild to moderately-severe in degree (range: 26 to 69 dB HL; mean: 46 dB HL; see Fig. 1). All participants had acquired hearing loss as adults, and 13 participants had used hearing aids for at least one year while 4 participants did not have prior experience with amplification. Audiometric slope was determined by calculating the dB/octave slope of the thresholds between 1000 and 4000 Hz. Participants obtained passing scores on a screening for cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al. 1975). All of the participants spoke American English as their primary language and were paid for their participation. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Arizona approved the research protocol.

Figure 1.

The average and range of behavioral pure tone air conduction thresholds.

Stimuli

The stimuli for the dual-task experiment were voice recordings of a male talker from the Revised-Speech in Noise Test (R-SPIN; Bilger et al. 1984). The R-SPIN is composed of 8 lists of 50 sentences with four-talker babble. Listeners were instructed to repeat the last word of each sentence. Half of the sentences were high context sentences in which the final word in each sentence was predictable, and half of the sentences were low context sentences in which the context did not help to predict the final word in the sentence. All sentence stimuli (70 dBA) and babble (variable level) were presented at 0° azimuth via a loudspeaker (NHT SuperOne, Benicia, California, USA).

Hearing Aids

All participants wore a pair of Phonak (Stafa, Switzerland) Naida IX UP (Spice Generation) hearing aids with custom foam tips for the study (Comply™ Canal Tips, Hearing Components, Oakdale, MN). Individualized fitting targets were created for each participant using the NAL-NL2 prescription procedure (Keidser et al. 2011). Real-ear verification measures confirmed hearing aid output within ±5 dB HL of each target frequency (250–6000 Hz) using the Aurical FreeFit (GN Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark) with an input level of 65 dBA while non-linear frequency compression was turned off. The hearing aids were set to omnidirectional mode with all noise management programs turned off and volume controls disabled.

Two hearing aid programs were created for testing: one program without non-linear frequency compression and one program with non-linear frequency compression activated. The non-linear frequency compression parameters were set according to the default settings recommended by the manufacturer’s fitting software (Phonak Target 3.0) for each participant (Cutoff frequency range: 3.5–4.6 kHz; Compression ratio range: 2.3:1–2.8:1). We did not include an acclimatization period; however, previous studies of non-linear frequency compression using an adult population did not find any significant improvement in speech recognition performance due to extended use of non-linear frequency compression (Hopkins et al. 2014; Ellis & Munro 2015a).

Audible bandwidth was calculated with and without non-linear frequency compression. The audible bandwidth was defined as the total input bandwidth contained within the real-ear aided output, from the lowest and up to the highest frequency at which each participant’s thresholds intersected with the aided output measured using real ear verification (McCreery et al., 2013). The input and output bandwidth calculations were made using input-output curves that were generated for each participant using an Aurical HIT test box based on stored real-ear data (GN Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark) with an input level of 65 dB SPL. Speech intelligibility indices for average-level conversation at 1 meter were calculated for each participant, both with and without frequency compression, using the Situational Hearing Aid Response Profile (SHARP) Version 7 (Stelmachowicz et al. 2013).

Procedures

Participants were seated in the center of a 12′ × 12′ double-walled sound booth, at a distance of 1 meter from a loudspeaker, which presented the stimuli from 0° azimuth at 70 dBA SPL. Participants responded by repeating words aloud, and their responses were captured by a ceiling-mounted microphone placed directly above the participant in the sound booth. Participants were blinded to the differences in settings between the hearing aid programs.

Because of the potential for large variation in speech perception in noise ability between participants, the signal to noise ratio (SNR) was set individually by finding the aided SNR (without non-linear frequency compression) corresponding to 50% correct performance. This was accomplished by varying the SNR from +20 dB to −8 dB SNR by changing the level of the multitalker babble in 4 dB steps, with six sentences tested per SNR (Wilson et al. 2012). Using the performance data at each SNR, the 50% correct performance point was calculated using the Spearman-Kärber equation (Finney 1952). Once the 50% performance SNR was set, each participant was tested with and without non-linear frequency compression in randomized order. The measured 50% SNR points for our participants ranged from −2 to +7 dB SNR (Mean= 2.87 dB SNR, SD= 3.93).

The experimental tasks used modifications to the R-SPIN test procedures, similar to those of Pichora-Fuller et al. (1995), which modified the test into a dual-task to measure listening effort (recall) in addition to speech perception in noise performance (see also Sarampalis et al. 2009). On each trial, the participants heard a sentence and had the primary task of repeating the last word of the sentence. After every six sentences, the participants had a secondary task of recalling as many previously reported words as possible. Previous studies with this dual-task method have used blocks of 2, 4, 6, or 8 sentences (Pichora-Fuller et al. 1995; Sarampalis et al. 2009). Pilot testing for the current study revealed that participants struggled to recall 8 sentence-final words, and the sentence blocks were reduced to 6 sentences for this study. Performance was scored for accuracy of recognition of the final word of each sentence and for the ability to recall the sentence-final words of every 6-sentence block. Scoring procedures did not penalize for recalling words out of order. Two lists from the R-SPIN were presented for each amplification condition for a total of 100 sentences per condition.

We assessed each participant’s working memory capacity using a sentence span task that was a modified version of Daneman and Carpenter’s (1980) Reading Span test (Waters, 1996; Waters & Caplan, 2003). Participants were visually presented with a sequential list of sentences to read (silently) on a computer monitor (iMo S10, Mimo Monitors, Princeton, NJ). After each sentence, participants firstly made a plausibility judgment as to whether the sentence made sense or not by pressing buttons on an E-prime 2.0 response box (Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Sharpsburg, PA) labeled “good” and “bad”. After each block of 2 to 6 sentences, the participants were tasked to recall the last word of each sentence in the order that they were presented. Test scores were calculated two ways: the total number of sentence-ending words repeated aloud correctly (total scoring) and the total number of words that were repeated in the proper order (serial scoring).

RESULTS

Speech Recognition in Noise

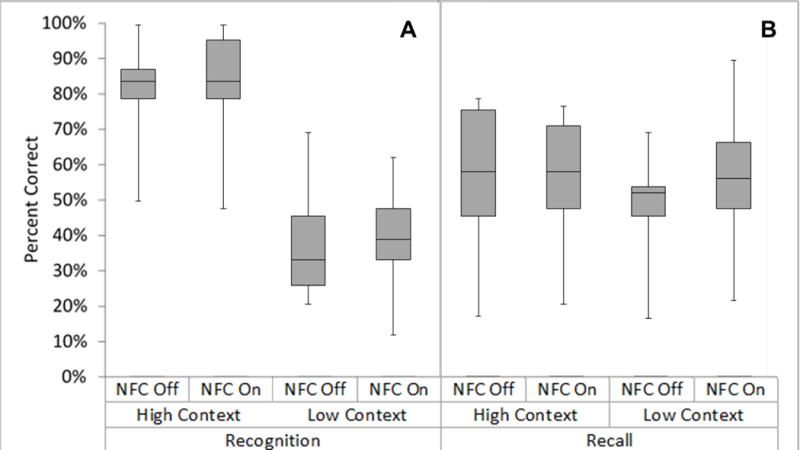

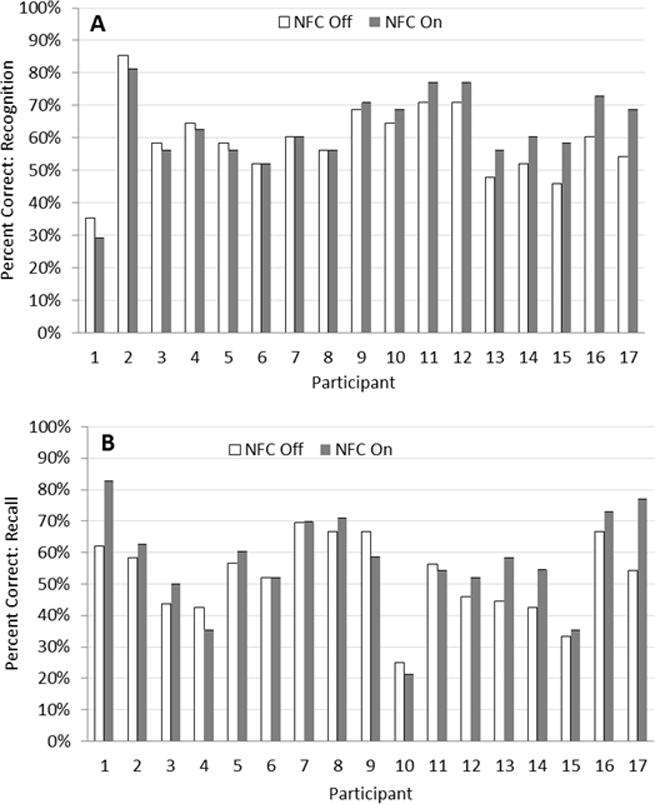

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to measure the effects of non-linear frequency compression (off vs. on) and sentence context (high context vs. low context) on speech recognition in noise, resulting in a 2×2 within-subjects ANOVA (Fig. 2, Panel A). There was a main effect of non-linear frequency compression for the recognition of speech in noise (F(1,16)=5.72, p=0.03, = 0.26), with higher speech recognition scores for non-linear frequency compression enabled (Mean=63%, SD=12%) than disabled (Mean = 59%, SD=12%). As predicted, the recognition of sentence-final words was better with high context (Mean=82%, SD = 12%) than low context (Mean=36%, SD=13%), and this main effect of context was statistically significant (F(1,16)=380.48, p<0.001, = 0.96). As seen in Figure 2, panel A, speech recognition improved by a greater amount with non-linear frequency compression on compared to off for low context sentences than it did for high context sentences. However, the interaction between non-linear frequency compression and context was not statistically significant (F(1,16)=1.98, p=0.18, = 0.11). At the individual level (Figure 3, Panel A), recognition scores increased with the addition of non-linear frequency compression for 9 of the 17 participants, ranging from 2% to 15% improvement combined across conditions.

Figure 2.

Boxplots for percent correct sentence-ending word recognition in noise (A) and word recall (B) with non-linear frequency compression off and on. Scores were averaged across high and low contexts.

Figure 3.

Percent of sentence-ending words correctly recognized (A) and recalled (B) with and without non-linear frequency compression (NFC) enabled. Participant scores are ordered from least recognition benefit to most recognition benefit with non-linear frequency compression.

Listening Effort

Figure 2, panel B illustrates performance on the recall task with and without non-linear frequency compression for low and high context sentences. Recall performance was analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA. The participants had significantly higher recall performance (F(1,16)=4.56, p=0.05, = .22) with non-linear frequency compression on (Mean=57%, SD=16%) than off (Mean=52%, SD=13%). There was no significant effect of context on recall performance (F(1,16)=2.09, p=0.17, = 0.12) and no significant interaction was observed between non-linear frequency compression and context (F(1,16)=1.30, p=0.27, = 0.08). At the individual level, 11 of the 17 participants improved in recall performance (2% to 23% benefit, Figure 3, Panel B). To determine whether individuals who received recall benefit from non-linear frequency compression were the same individuals who received recognition benefit, a simple linear regression was conducted and no significant correlation was found between recognition benefit and recall benefit (r=0.14, p=0.57). Benefit scores were averaged across context for this analysis since there was no significant interaction between context and benefit from non-linear frequency compression. The lack of a significant correlation between recognition and recall benefit would suggest that different individuals received benefits for different reasons which are explored below.

Individual Differences

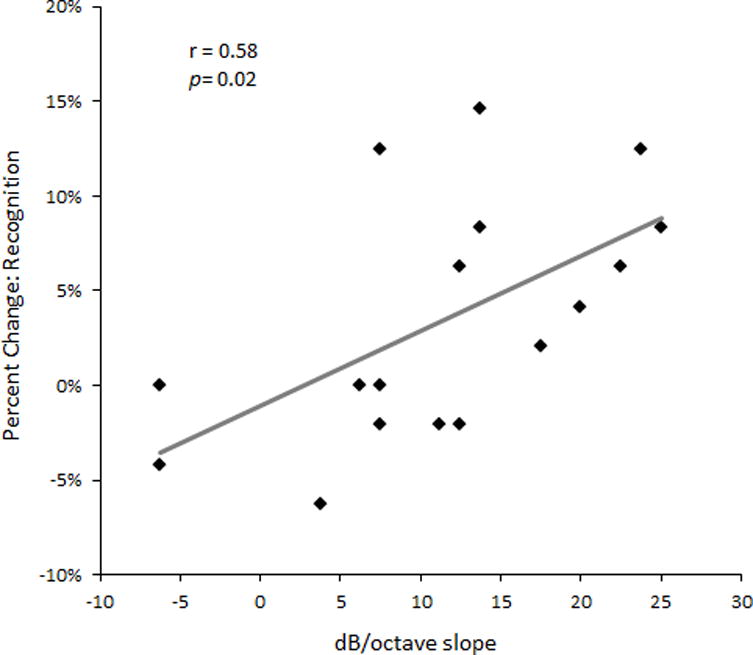

The second aim of the study was to evaluate the intrinsic factors that may influence individual differences in aided benefit or detriment from non-linear frequency compression. Based on previous studies, we examined the influence of hearing loss slope and severity, audible bandwidth, working memory capacity, and age on the amount of change with non-linear frequency compression for speech recognition in noise and listening effort using simple multiple linear regression modeling. See Table 1 for results of correlational analysis of the predictor variables. Because hearing loss slope and severity correlated significantly with one another, hearing loss severity was excluded from the regression modeling. For the significant improvement in recognition performance due to non-linear frequency compression, the only significant predictor variable was hearing loss slope. Audible bandwidth, Sentence Span scores, and age all had poor prediction values (p>0.20) and were excluded from the regression model. As predicted, participants with more steeply sloping hearing losses received more benefit from non-linear frequency compression (R2=0.33, F(1,15)=7.42, β=0.58, p=0.02; see Fig. 4). Surprisingly, Sentence Span score (p=0.64) and audible bandwidth (p=0.23) were not significant predictors of speech recognition benefit from non-linear frequency compression and were excluded from the model. Audible bandwidth was not a significant predictor even though a statistically significant increase in audible bandwidth for our listeners due to non-linear frequency compression was observed (F(1,16)=21.36, p<0.001, = .57) with the average audible bandwidth improving from 4.3 kHz (SD=0.6) to 5 kHz (SD=1.2).

Table 1. Predictor Variable Correlation Table.

Correlation table for individual predictor variables of age, four tone pure tone average (PTA, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz average), slope of hearing loss (dB/octave change between 1–4 kHz), audible bandwidth, and Sentence Span test total item scores.

| Age | Four Tone PTA | Slope | Audible Bandwidth | Sentence Span | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age | Pearson r | 1 | −0.03 | 0.37 | −0.61** | −0.45 |

| p | – | 0.92 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.07 | |

|

| ||||||

| Four Tone PTA | Pearson r | −0.03 | 1 | −0.51* | −.017 | −0.36 |

| p | 0.92 | – | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.16 | |

|

| ||||||

| Slope | Pearson r | 0.37 | −0.51* | 1 | −0.57* | −0.10 |

| p | 0.15 | 0.04 | – | 0.02 | 0.71 | |

|

| ||||||

| Audible Bandwidth | Pearson r | −0.61** | −0.02 | −0.57* | 1 | 0.06 |

| p | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.02 | – | 0.81 | |

|

| ||||||

| Sentence Span | Pearson r | −0.45 | −0.36 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 1 |

| p | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.71 | 0.81 | – | |

p < .05,

p <.01

Figure 4.

Correlation between the change in recognition performance with and without non-linear frequency compression and slope of hearing loss, calculated as the threshold slope between 1–4 kHz.

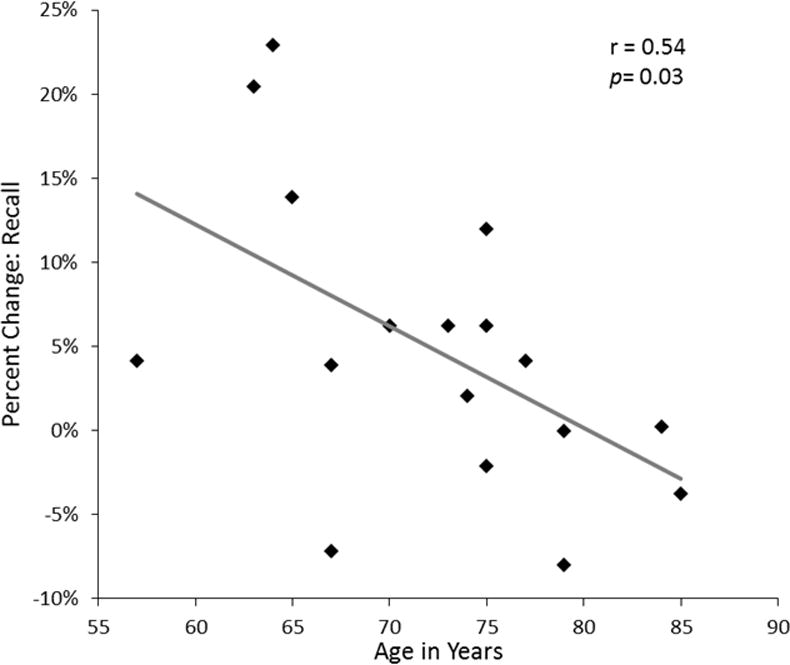

We used simple multiple linear regression modeling again to determine which listener variables contributed most to the significant improvement in recall performance due to non-linear frequency compression. The only significant predictor variable was participant age, and the other predictor variables were excluded from the model. Change in recall performance significantly and negatively correlated with participant age (R2=0.29, F (1,15)=6.094, β=−0.54, p=0.03; see Figure 5). Since age rather than working memory capacity correlated with recall performance, it is possible that Sentence Span test scores alone are not enough to capture age-related cognitive changes, given that the younger participants received significantly more recall benefit due to non-linear frequency compression. Additionally, the correlation between Sentence Span scores and age approached but did not reach significance (Serial Scoring: r=−0.45, p=0.08; Total Score: r=−0.45, p=0.07). The Sentence Span mean raw scores were 43.7 items correct (SD=14.5; Range=22–72) for serial scoring and 48.8 items correct (SD=14.86; Range=31–77) for total scores.

Figure 5.

Correlation between the change in recall performance with and without non-linear frequency compression and age in years.

DISCUSSION

The effects of non-linear frequency compression on speech recognition in noise and listening effort were assessed in this study in an older adult population with hearing loss. The main findings were that on average, activating the non-linear frequency compression setting resulted in improved speech recognition performance for low but not high context sentences and reduced listening effort. Improvements in listening to and remembering speech in background babble indicate that some, though not all, adults with mild to severe hearing loss can receive benefit from non-linear frequency compression in a noisy environment.

Effects of Non-Linear Frequency Compression

One objective for this study was to manipulate the extrinsic factor of sentence context. We predicted that minimal benefit from non-linear frequency compression would be observed in high context listening conditions, since participants would have access to contextual information to support the explicit processing of presented sentences. Greater improvement, on average, in recognition performance for low context sentences due to non-linear frequency compression was observed. However, the interaction between non-linear frequency compression and sentence context was not statistically significant. Conversely, the relatively good performance even without non-linear frequency compression for high context sentences may have operated as a ceiling effect, limiting the potential benefit from non-linear frequency compression.

For the sentences with high context, participants were likely able to use contextual cues to predict the final word and avoid the need for explicit processing (Wingfield et al. 2015). Older adults have been found to be especially proficient at making use of sentence context in adverse listening conditions (e.g., Pichora-Fuller et al. 1995), which is likely why less benefit from non-linear frequency compression was observed in high context than in low context sentences. If true, then the use of high context sentences in Picou et al. (2015) could explain why they did not observe a benefit of non-linear frequency compression for sentence recognition in noise. Their study used the Connected Speech Test (Cox et al. 1987, 1988), which is rich in context, allowing the older listeners to make use of their conceptual and semantic knowledge to accommodate a degraded speech signal (Aydelott et al. 2010). Conversely, context neutral sentences force listeners to depend more heavily on the acoustic signal (Kalikow et al. 1977; Pichora-Fuller et al. 1995). In real world listening conditions, such as a conversation at a restaurant with a group of several talkers, listeners with hearing loss may not always have context-rich listening conditions. For example, when switching attention between multiple talkers or monitoring several conversations simultaneously, the predictability of speech is diminished. Listeners in noisy listening environments often do not have access to the context of each conversation, especially individuals with hearing loss, and as a result they must exert more effort to follow each conversation or may even avoid participation in the conversation (Pichora-Fuller et al. 1995; Desjardins & Doherty 2013).

In the present study, we also measured aided listening effort within a dual-task paradigm while using non-linear frequency compression. Previous studies using a similar paradigm found reduced listening effort using digital noise reduction processing for normally hearing listeners (Sarampalis et al. 2009) and adults fitted with hearing aids (Desjardins & Doherty 2014). Likewise, we found recall performance on average was significantly better when non-linear frequency compression was enabled. Interpreted through the ELU model, our findings suggest that non-linear frequency compression may have improved the phonological representation of the speech signal during the recognition task. The improved phonological representation would reduce the listening effort necessary for the processing of the speech signal, enabling our listeners to expend more cognitive resources on the recall task.

Individual Differences

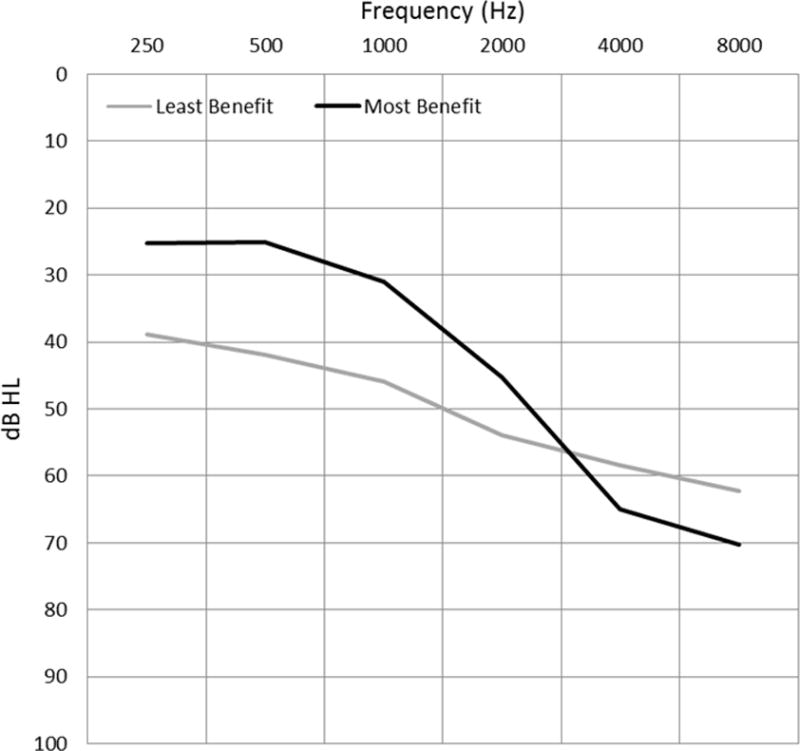

A secondary goal for this study was to determine the impact of intrinsic factors of hearing loss slope, working memory capacity and age on the effects of non-linear frequency compression for speech recognition and recall in noise. When considering speech recognition in noise, we firstly examined how individual factors related to performance while manipulating sentence context. Non-linear frequency compression significantly improved recognition performance. The only intrinsic factor found to correlate with non-linear frequency compression benefit for speech recognition in noise was hearing loss slope; individuals who had more steeply sloping hearing losses received more benefit. For demonstration purposes, Figure 6 illustrates the hearing loss configuration for the participants with the least amount of recognition benefit (Group A) and the most recognition benefit (Group B) from non-linear frequency compression. Note that the participants who received more recognition benefit from non-linear frequency compression had on average more steeply sloping hearing losses. Ellis and Munro (2015b) also found that non-linear frequency compression benefit correlated with high-frequency pure tone average (2000-6000 Hz). Two recent studies did not find significant improvements is speech recognition performance with non-linear frequency compression possibly due to using the NAL-NL1 prescription gain formula, which applies less high-frequency gain than the NAL-NL2 prescription gain formula (Hopkins et al. 2014; Picou et al., 2015). Reduced high-frequency gain would result in fewer high-frequency cues being compressed into audible frequency regions potentially limiting the effect that non-linear frequency compression may have on speech recognition performance. Our study, similar to the studies that did find improvements in speech recognition due to non-linear frequency compression (Ellis & Munro 2015a, 2015b), made use of the NAL-NL2 prescription fit formula, instead, which may have provided more high-frequency cues than an NAL-NL1 prescription fitting would have.

Figure 6.

Average pure tone thresholds for individuals who received the least benefit (-9% to +5% change; Group A) and the most benefit (+5% to +22% change; Group B) for speech recognition performance with non-linear frequency compression in low context sentences.

We also evaluated the contribution of working memory capacity for the effect of non-linear frequency compression on recall. However, in the current study, age rather than working memory capacity correlated with benefit from non-linear frequency compression on recall performance. Benefit of non-linear frequency compression on recall negatively correlated with age, meaning younger participants received more recall benefit than older participants. Previous research concerning speech perception performance with hearing aid processing strategies such as digital noise reduction, frequency lowering, and compression attack and release times found that potential benefit from these hearing aid strategies were positively correlated with working memory capacity based on Reading Span test scores (Lunner et al. 2009; Arehart et al. 2013; Ng et al. 2013; Souza & Sirow 2014), which is something we did not observe in this study. One potential reason is that we made use of a different version of the measure. The original version of the Reading Span test was designed to have participants recall only the last words of each sentence (Daneman & Carpenter 1980), which is the method we used for this study. Other studies which found the significant correlation with Reading Span test scores required participants to repeat either the first words or the last words of each sentence, and the participants were not informed which words were to be recalled until after each block of sentences was completed. By knowing a priori that only the last words of each sentence were to be recalled, it is possible that our participants were better able to make use of memory strategies, such as sub-vocal rehearsal, than if they did not know which words they were going to be tasked to recall. However, the participants were instructed not to rehearse the sentence-ending words and the primary plausibility judgment task would have made rehearsal difficult.

Working memory capacity was not a significant factor in benefit from non-linear frequency compression for either recall or recognition performance in our study. Others have reported that the relation between working memory and response to non-linear frequency compression is mixed (Ellis & Munro 2015). As discussed in a recent review by Souza, Arehart, and Neher (2015a), one possibility is that within studies using commercially available hearing aids, such as Ellis & Munro (2015b) and the present study, each listener received a different amount of signal processing whereas in other studies showing a relationship between working memory (reading span) and non-linear frequency compression, all participants received the same amount of processing. It is also possible that the Sentence Span Test as a measure of working memory capacity may not capture all age-related cognitive changes that may contribute to speech recognition performance and potential benefit from hearing aid processing strategies. Other measures that may be helpful in determining the cognitive status of participants could include tests that specifically measure executive function, attention, and processing speed (Akeroyd 2008). Future studies should consider the use of a broader cognitive test battery to capture additional age-related changes in cognition (Rönnberg et al. 2016).

Clinical Implications

The present findings are relevant for clinical practice because dispensing audiologists must decide when to apply non-linear frequency compression. We found improvements in word recognition and recall in background babble, indicating that some, though not all, adults with mild to moderately-severe hearing loss can receive benefit from non-linear frequency compression in a noisy environment. These findings add to the evidence base documenting that the benefit of non-linear frequency compression varies across individuals (Glista et al. 2009; Picou et al. 2015). Our findings support the conclusion that non-linear frequency compression may be useful for patients with steeply sloping hearing loss, though clinical expectations for the amount of benefit may be tempered by an individual’s age. Within our sample, the amount of change in performance by enabling non-linear frequency compression in the hearing aids ranged from −8% to 22% in speech recognition and −8% to 23% in scores for recall from memory. Further, scores on these outcome measures were not correlated with one another, suggesting that adult listeners may experience reduced listening effort even when recognition performance is unchanged. Our data suggest that adults with more steeply sloping sensorineural hearing loss may receive speech recognition benefit from non-linear frequency compression in low-context, noisy listening conditions.

Taken together, these findings add to the evidence base supporting patient-centered hearing aid feature selection. Specifically, the data suggest that candidacy for non-linear frequency compression should be assessed on a patient-by-patient basis, taking into consideration the expected variability in benefit for speech recognition and listening effort. In clinical settings, assessment of hearing aid outcomes may need to go beyond measures of speech recognition in noise to include listening effort (Johnson et al. 2015; Lunner et al. 2016). Future research is indicated with a larger data set on the dual-task paradigm of speech recognition and listening effort as a potential cognitive outcome measure that is sensitive to differences in hearing technology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants in the study for volunteering their time, the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback and insight, Dr. Andrea Pittman for helpful discussions of the study results, and Dr. Gayle DeDe for providing the Sentence Span test materials. The authors also thank the University of Arizona Hearing Clinic for lending the hearing aids used in this study to the laboratory. Funding for this study was provided by the research grant associated with the James S. and Dyan Pignatelli/Unisource Clinical Chair in Audiologic Rehabilitation for Adults at The University of Arizona. Preliminary data were presented at the AudiologyNOW! meeting April, 2013 and at the International Conference of Cognitive Hearing Science for Communication meeting, June, 2013.

Financial Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest:

Funding for this study was provided by the research grant associated with the James S. and Dyan Pignatelli/Unisource Clinical Chair in Audiologic Rehabilitation for Adults at The University of Arizona.

References

- Akeroyd MA. Are individual differences in speech reception related to individual differences in cognitive ability? A survey of twenty experimental studies with normal and hearing-impaired adults. International Journal of Audiology. 2008;47(S2):S53–S71. doi: 10.1080/14992020802301142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JM. Individual variability in recognition of frequency-lowered speech. Seminars in Hearing. 2013;34(2):86–109. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JM, Kopun JG, Stelmachowicz PG. Effects of frequency compression and frequency transposition on fricative and affricate perception in listeners with normal hearing and mild to moderate hearing loss. Ear and Hearing. 2014;35(5):519–532. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arehart KH, Souza P, Baca R, et al. Working memory, age and hearing loss: susceptibility to hearing aid distortion. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34(3):251–260. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318271aa5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydelott J, Leech R, Crinion J. Normal adult aging and the contextual influences affecting speech and meaningful sound perception. Trends in Amplification. 2010;14(4):218–232. doi: 10.1177/1084713810393751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer T, Moore BC, Kluk K. Effects of low pass filtering on the intelligibility of speech in noise for people with and without dead regions at high frequencies. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2002;112(3):1133–1144. doi: 10.1121/1.1498853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger RC, Nuetzel JM, Rabinowitz WM, et al. Standardization of a test of speech perception in noise. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1984;27(1):32–48. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2701.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A, Nyffeler M, Keilmann A. Advantages of a non-linear frequency compression algorithm in noise. European Archives of Oto-rhino-laryngology. 2010;267(7):1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-1170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan MA, McCreery R, Kopun J, et al. Paired Comparisons of Nonlinear Frequency Compression, Extended Bandwidth, and Restricted Bandwidth Hearing Aid Processing for Children and Adults with Hearing Loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2014;25(10):983–998. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.25.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne D, Dillon H, Ching T, Katsch R, Keidser G. NAL-L1 procedure for fitting nonlinear hearing aids: Characteristics and comparisons with other procedures. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2001;12(1):37–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RM, Alexander GC, Gilmore C. Development of the Connected Speech Test (CST) Ear and Hearing. 1987;8(5):119S–126SS. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198710001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RM, Alexander GC, Gilmore C, et al. Use of the Connected Speech Test (CST) with hearing-impaired listeners. Ear and Hearing. 1988;9(4):198–207. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198808000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1980;19(4):450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins JL, Doherty KA. Age-related changes in listening effort for various types of masker noises. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34(3):261–272. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31826d0ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins JL, Doherty KA. The effect of hearing aid noise reduction on listening effort in hearing-impaired adults. Ear and Hearing. 2014;35(6):600–610. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Munro KJ. Benefit from, and acclimatization to, frequency compression hearing aids in experienced adult hearing-aid users. International Journal of Audiology. 2015a;54(1):37–47. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.948217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Munro KJ. Predictors of aided speech recognition, with and without frequency compression, in older adults. International Journal of Audiology. 2015b;54(7):467–475. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.996825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney DJ. Statistical method in biological assay. Vol. 8. London: Griffin; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glista D, Scollie S, Bagatto, et al. Evaluation of nonlinear frequency compression: Clinical outcomes. International Journal of Audiology. 2009;48(9):632–644. doi: 10.1080/14992020902971349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins K, Khanom M, Dickinson, et al. Benefit from non-linear frequency compression hearing aids in a clinical setting: The effects of duration of experience and severity of high-frequency hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology. 2014;53(4):219–228. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.873956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby BW. The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34(5):523–534. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828003d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby BW, Johnson EE, Picou E. Effects of degree and configuration of hearing loss on the contribution of high-and low-frequency speech information to bilateral speech understanding. Ear and Hearing. 2011;32(5):543–555. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31820e5028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Xu J, Cox R, Pendergraft P. A comparison of two methods for measuring listening effort as part of an audiologic test battery. American Journal of Audiology. 2015;24(3):419–431. doi: 10.1044/2015_AJA-14-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalikow DN, Stevens KN, Elliott LL. Development of a test of speech intelligibility in noise using sentence materials with controlled word predictability. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;61(5):1337–1351. doi: 10.1121/1.381436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keidser G, Dillon HR, Flax M, et al. The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiology Research. 2011;1(1):e24. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2011.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan CA, Turner CW. High-frequency audibility: Benefits for hearing-impaired listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;104(1):432–441. doi: 10.1121/1.423247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby BW. The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34(5):523–534. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828003d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann RP. Accurate consonant perception without mid-frequency speech energy. IEEE Transactions on Speech and Audio Processing. 1996;4(1):66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lunner T, Rudner M, Rönnberg J. Cognition and hearing aids. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2009;50(5):395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunner T, Rudner M, Rosenbom T, Ågren J, Ng EHN. Using speech recall in hearing aid fitting and outcome evaluation under ecological test conditions. Ear and Hearing. 2016;37:145S–154S. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SL, Tun PA, Cox LC, Colangelo M, Stewart RA, Wingfield A. Hearing loss and perceptual effort: Downstream effects on older adults’ memory for speech. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 2005;58(1):22–33. doi: 10.1080/02724980443000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreery RW, Brennan MA, Hoover B, et al. Maximizing audibility and speech recognition with non-linear frequency compression by estimating audible bandwidth. Ear and Hearing. 2013;34(2):e24–e27. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31826d0beb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott H, Henshall K. The use of frequency compression by cochlear implant recipients with postoperative acoustic hearing. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2010;21(6):380–389. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.21.6.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarrigle R, Munro KJ, Dawes P, et al. Listening effort and fatigue: What exactly are we measuring? A British Society of Audiology Cognition in Hearing Special Interest Group ‘white paper’. International Journal of Audiology. 2014;53(7):433–445. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.890296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson BB, Hunter EJ, Lotto AJ, et al. The perceptual significance of high-frequency energy in the human voice. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, article 587. 2014:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BB., Jr The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1962;65(5):482. [Google Scholar]

- Ng EHN, Rudner M, Lunner T, et al. Effects of noise and working memory capacity on memory processing of speech for hearing-aid users. International Journal of Audiology. 2013;52(7):433–441. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.776181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichora-Fuller MK. Use of supportive context by younger and older adult listeners: Balancing bottom-up and top-down information processing. International Journal of Audiology. 2008;47(sup2):S72–S82. doi: 10.1080/14992020802307404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichora‐Fuller MK, Schneider BA, Daneman M. How young and old adults listen to and remember speech in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1995;97(1):593–608. doi: 10.1121/1.412282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picou EM, Marcrum SC, Ricketts TA. Evaluation of the effects of nonlinear frequency compression on speech recognition and sound quality for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology. 2015;54(3):162–169. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.961662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnberg J, Lunner T, Ng EHN, Lidestam B, Zekveld AA, Sörqvist P, Hällgren M. Hearing impairment, cognition and speech understanding: exploratory factor analyses of a comprehensive test battery for a group of hearing aid users, the n200 study. International Journal of Audiology. 2016;55(11):623–642. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1219775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnberg J, Lunner T, Zekveld A, et al. The Ease of Language Understanding (ELU) model: theoretical, empirical, and clinical advances. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 7. 2013:1–17. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00031. article 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnberg J, Rudner M, Foo C, et al. Cognition counts: A working memory system for ease of language understanding (ELU) International Journal of Audiology. 2008;47(sup2):S99–S105. doi: 10.1080/14992020802301167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner M, Ng HN, Rönnberg N, Mishra S, Rönnberg J, Lunner T, Stenfelt S. Cognitive spare capacity as a measure of listening effort. Journal of Hearing Science. 2011;1(2):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sarampalis A, Kalluri S, Edwards B, et al. Objective measures of listening effort: Effects of background noise and noise reduction. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52(5):1230–1240. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0111). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A, Hersbach AA, McDermott HJ. Improvements in speech perception with an experimental nonlinear frequency compression hearing device. International Journal of Audiology. 2005;44(5):281–292. doi: 10.1080/14992020500060636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A, Hersbach AA, Mcdermott HJ. Frequency-compression outcomes in listeners with steeply sloping audiograms. International Journal of Audiology. 2006;45(11):619–629. doi: 10.1080/14992020600825508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SL, Pichora-Fuller MK, Alexander G. Development of the Word Auditory Recognition and Recall Measure: A Working Memory Test for Use in Rehabilitative Audiology. Ear and Hearing. 2016;37(6):e360–e376. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza P, Arehart K, Neher T. Working Memory and Hearing Aid Processing: Literature Findings, Future Directions, and Clinical Applications. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. 2015a:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01894. article 1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza PE, Arehart KH, Shen J, Anderson M, Kates JM. Working memory and intelligibility of hearing-aid processed speech. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. 2015b:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00526. article 526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza PE, Sirow L. Relating working memory to compression parameters in clinically fit hearing aids. American Journal of Audiology. 2014;23(4):394–401. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelmachowicz P, Lewis D, Kalberer A, Creutz T. User’s Manual, Situational Hearing Aid Response Profile (SHARP, Version 2.0) Boys Town National Research Hospital; Omaha, Nebraska: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stelmachowicz PG, Pittman AL, Hoover BM, et al. Effect of stimulus bandwidth on the perception of/s/in normal-and hearing-impaired children and adults. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2001;110(4):2183–2190. doi: 10.1121/1.1400757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun PA, McCoy S, Wingfield A. Aging, hearing acuity, and the attentional costs of effortful listening. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24(3):761–766. doi: 10.1037/a0014802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente M, Abrams H, Benson D, Chisolm T, Citron D, Hampton D, Sweetow R. Guidelines for the audiologic management of adult hearing impairment. Audiology Today. 2006;18(5):32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Waters GS. The measurement of verbal working memory capacity and its relation to reading comprehension. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Section A. 1996;49(1):51–79. doi: 10.1080/713755607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters GS, Caplan D. The reliability and stability of verbal working memory measures. Behavioral Research Methods. 2003;35(4):550–564. doi: 10.3758/bf03195534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RH, McArdle R, Watts KL, et al. The Revised Speech Perception in Noise Test (R-SPIN) in a multiple signal-to-noise ratio paradigm. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2012;23(8):590–605. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.7.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield A, Amichetti NM, Lash A. Cognitive aging and hearing acuity: Modeling spoken language comprehension. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. 2015:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00684. article 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield A, Tun PA, McCoy SL. Hearing loss in older adulthood what it is and how it interacts with cognitive performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(3):144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J, John A, Schafer E, et al. Evaluation of nonlinear frequency compression for school-age children with moderate to moderately severe hearing loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 2010;21(10):618–628. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.21.10.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J, John A, Schafer E, et al. Long-term effects of non-linear frequency compression for children with moderate hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology. 2011;50(6):396–404. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2010.551788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]