Abstract

Prevention can help older patients avoid illness by identifying and addressing conditions before they cause symptoms. However, prevention can also harm older patients if conditions that are unlikely to cause symptoms in the patient’s lifetime are identified and treated. To identify older patients who are most likely to benefit (and most likely to be harmed) by preventive interventions, we propose a framework that compares a patient’s life expectancy (LE) with the time to benefit (TTB) for an intervention. If the LE << TTB, the patient in unlikely to benefit but is exposed to the risks of the intervention. Thus, the intervention should generally NOT be recommended. If the LE >> TTB, the patient could benefit and the intervention should generally be recommended. If the LE ~ TTB, the decision is a “close call” and the patient’s values and preferences should be the major driver of the decision. To facilitate the use of this framework in routine clinical care, we 1) explore ways to estimate LE, 2) identify the TTB for common preventive interventions and 3) recommend strategies for communicating with patients. We synthesize these strategies and demonstrate how they can be used to individualize prevention for a hypothetical patient in the setting of a Medicare Annual Wellness Visit. Finally, we place prevention in the context of curative and symptom-oriented care and outline how prevention should be focused on healthier older adults, while symptom-oriented care should predominate in sicker older adults.

Keywords: Prevention, Life Expectancy, Time to Benefit, Cancer Screening

Introduction

Prevention holds the promise of maintaining good health by testing, diagnosing and treating conditions before they cause symptoms. The idea of avoiding illness is tremendously popular,1 and led to the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit, which reimburses providers for a visit focusing on prevention in older adults.2

However, prevention has the potential to harm as well as help.3 Prevention requires interventions (tests or treatments) for asymptomatic conditions which can cause immediate complications, with the hope of improved health in the future. “Time to benefit” (TTB) is defined as the time between the preventive intervention (when complications and harms are most likely) to the time when improved health outcomes are seen.4,5 Just as different interventions have different magnitudes of benefit, different preventive interventions have different times to benefit, with estimates ranging from 6 months (statin therapy for secondary prevention) to >10 years (prostate cancer screening).6

For older adults, the time to benefit, or the answer to the question “When will it help?”, is a critical factor in determining whether a preventive intervention is more likely or help or harm. For older adults whose life expectancy (LE) is substantially shorter than the time to benefit for a preventive intervention (LE << TTB), performing that intervention exposes them to the immediate risks of the intervention with little likelihood of surviving long enough to benefit.4,7,8 In addition, the factors associated with limited life expectancy (such as increased age, comorbidities and functional limitations) are strong risk factors for complications of interventions.9 Thus, older patients who are least likely to benefit because of limited life expectancy are also most likely to be harmed from the complications of prevention. Many guidelines now explicitly endorse the central role of life expectancy in targeting prevention, recommending preventive interventions such as cancer screening only for those patients with an extended life expectancy.10–13

To maximize the chances that patients are helped (rather than harmed) by prevention, we propose a framework to individualize prevention that focuses on comparing an older patient’s life expectancy (LE) with the intervention’s time to benefit (TTB). Then, we will provide guidance on 1) determining LE for individual patients, 2) TTB for different interventions and 3) communicating with patients. We will highlight how this framework could be applied in the context of an Annual Wellness Visit. Finally, we will conclude by placing prevention in the context of other healthcare needs in older adults.

Framework for Individualized Prevention

We propose juxtaposing estimated life expectancy with the estimated time to benefit in decision making for all preventive interventions in older adults. Specifically, life expectancy should be estimated for each patient and the time to benefit for preventive interventions should be determined. When the life expectancy is substantially greater than the time to benefit, the intervention should be recommended since it is more likely that the patient will benefit than be harmed by the intervention. Conversely, when the time to benefit is less than the life expectancy, the intervention should not be recommended, since it is more likely to harm than help the patient. When the life expectancy is close to the time to benefit, the benefits versus harms of the preventive intervention are a “close call” and patient preferences (e.g., the degree of importance placed on the potential benefits and harms) should play the dominant role in whether the preventive intervention is recommended.

How to Estimate Life Expectancy

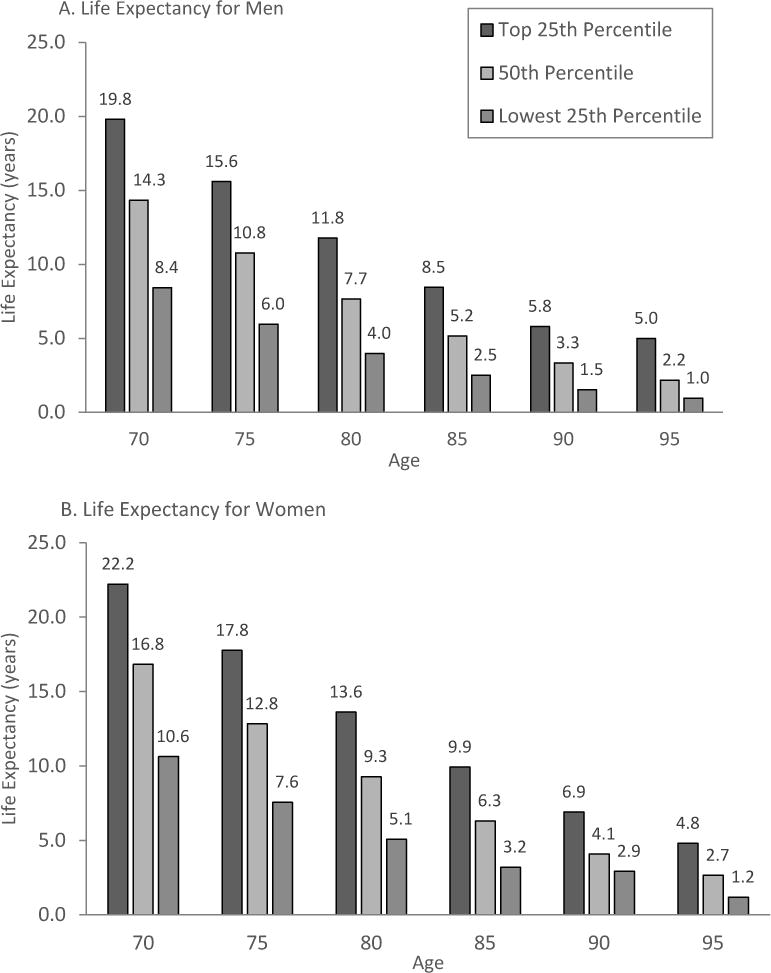

We will highlight 2 ways to estimate life expectancy for older adults. First, US life table data can be used to estimate life expectancy for the average person at any age. To account for patients who may be healthier (or less healthy) than average, life tables can provide the life expectancy of the healthiest quartile and least healthy quartile.7 (Figure 1) To use these tables, a clinician must first estimate whether their patient (compared to others the same age) is in the healthiest quartile, least healthy quartile or, in one of the middle quartiles. Then, the clinician can find the appropriate age and gender data which provides an estimate of life expectancy for the patient.

Figure 1.

Upper, Middle and Lower Quartiles of Life Expectancy for Women and Men at Selected Ages

From US life table data available at: https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html

Adapted from: Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA 2001;285:2750-6.

The second way to estimate life expectancy uses previously developed mortality indexes. A systematic review identified 16 unique mortality indexes for older adults across a variety of settings (e.g. hospitalized patients, patients in the nursing home and patients being seen in clinic).6 To facilitate use by clinicians, these mortality indexes have been compiled and translated into online calculators at ePrognosis.com. To use these indexes, a clinician needs to enter the data elements required for the specific index (i.e. age, gender, comorbidities, functional limitations) and the website will provide the predicted mortality risk or life expectancy.

How to Estimate Time to Benefit

While the measures and methodologies to quantify the magnitude of benefit (i.e. relative risk reduction or number needed to treat) have been standardized and are now widely accepted, the methodology to estimate time to benefit remains relatively novel. We developed and published a survival meta-analysis methodology to quantify the time to benefit between breast and colorectal cancer screening and observed mortality reduction.4,14 Combining data from high-quality trials of screening mammography, we found that to prevent 1 breast cancer death for 1000 women screened, it would take 10.7 years (95% CI: 4.4, 21.6) to achieve this magnitude of benefit.4 Similarly, to prevent 1 colorectal cancer death for 1000 persons screened with flexible sigmoidoscopy, it would take 9.4 years (95% CI: 7.6, 11.3) to achieve this benefit. Since major complications from screening occur in approximately 1 in 1000 persons, we believe that targeting cancer screening to those adults with a life expectancy >10 years will maximize the benefits and minimize the harms of breast and colorectal cancer screening.

A second methodology for determining time to benefit was described by van de Glind and colleagues, which relied on statistical process control methods to estimate the time to decreased fracture risk with alendronate. Re-analyzing data from the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT), they found that for women <70, the time to benefit is 19 months while for women ≥70, the time to benefit is 8 months.15 Both methods calculate a time to benefit (e.g. 1.5 years to achieve an absolute risk reduction of 5%) by re-examining data from trials that report magnitude of benefit for a fixed time interval (e.g. HR 0.80 for median follow-up of 3.5 years). Going forward, the ideal solution would be for all trials of interventions for older adults to report a time to benefit, which would obviate the need for subsequent analyses to estimate time to benefit.3

Times to Benefit for Specific Interventions

Table 1 provides a summary of times to benefit for preventive interventions, ranging from bisphosphonates for osteoporosis (8 – 19 months) to prostate cancer screening (10 – 15 years). For primary prevention of cardiovascular events for hypertension, a recent review suggested that the time to benefit is 1–2 years.16 Studies that included secondary prevention and studies that focused stroke outcomes generally showed shorter times to benefit.16 The recent SPRINT trial (which included some secondary prevention patients with baseline cardiovascular disease) suggested that for patients over age 75, those who are fit with a lower baseline risk of events have a longer time to benefit (~2 years) while frail patients with a higher baseline risk of events have a shorter time to benefit (~1 year).17

Table 1.

Time to Benefit for Preventive Interventions for Older Adults

| Time to Benefit (years) |

Preventive Intervention | Guideline? | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 mos – 19 mos | Bisphosphonates for Osteoporosis | none | 15 |

| 1 – 2 | Primary prevention, hypertension | none | 16,17,31 |

| 2 – 5 | Primary prevention with statins | none | 16,18–20,32 |

| 5 | Surgical (vs Transcatheter) Aortic valve replacement for High risk Aortic Stenosis | none | 33 |

| 6 – 8 | Open (vs Endovascular) Repair for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm | none | 23 |

| 10 | Aspirin for Cardiovascular disease and Colorectal Cancer prevention | USPSTF | 34 |

| 10 | Intensive Glycemic Control in Diabetes mellitus | American Geriatrics Society | 35 |

| 10 | Colorectal Cancer Screening | USPSTF, American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine |

1,36–38 |

| 10 | Breast Cancer Screening | Society of General Internal Medicine, American College of Physicians |

1,37,38 |

| 10–15 | prostate cancer screening | American Urological Association, American College of Physicians |

11,22,37 |

USPSTF is the US Preventive Services Task Force

For primary prevention of cardiovascular events for hyperlipidemia using statins, a narrative review found that the time to decrease myocardial infarction ranged from 2 – 5 years.18 Although only few studies report time to benefit data, studies that focused on younger patients reported shorter time to benefit (ACAPS study, mean age 61, time to benefit 1.5 years19) compared to studies that focused on older patients (JUPITER study, mean age 66, time to benefit 2.5 – 3 years).18,20 A recent meta-analysis focusing on trials reporting results for adults over age 65 found that statins decreased risk for myocardial infarction and stroke, but did not decrease cardiovascular or all-cause mortality over 3.5 years.16,21

For prostate cancer screening, the American Urological Association review noted that there was strong evidence of lack of treatment benefit in men with life expectancy below 10 – 15 years.11 Specifically, the SPCG-4 trial found that for men age 65 and older, prostate cancer treatment (radical prostatectomy) did not decrease all-cause or prostate cancer mortality compared to watchful waiting at 15 years, suggesting that while the prostate cancer screening time to benefit may be 10 years for those younger than 65, the time to benefit for those older than 65 is >15 years.22

In addition to preventive interventions, time to benefit can also inform decisions about procedures when one procedure has better longer term outcomes but a second procedure has better shorter term outcomes. For example, for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, endovascular procedures result in better short term outcomes (i.e. less pain, lower short-term mortality), but worse long term outcomes (i.e. increased risk of late graft failure and need for re-intervention) compared to open surgical repair. Current data suggests that it takes 6–8 years for the long-term benefits of open surgical repair to outweigh the short-term risks, suggesting patients with a life expectancy > 6–8 years may be better served with open surgical repair.23

How to Communicate the Balance between the Benefits and Harms of Prevention

One barrier to implementing this framework is the challenge of communicating the rationale for starting, stopping or continuing preventive interventions.24 While some patients want to discuss life expectancy, many do not,25 citing the inherent uncertainty with any prediction as well as the discomfort brought on by the topic.26 Thus, while the framework of life expectancy and time to benefit may be useful from a population health perspective, when communicating with patients, it may be better to focus on the most likely end results of screening. Specifically, one study found that patients respond negatively to statements such as, “You may not live long enough to benefit from this test.”26 In contrast, patients responded much more positively to statements such as, “This test isn’t going to help you live longer,” 27 or “This test is more likely to hurt you than help you.”26 One resource that models best practices in prognosis communication are videos available at http://ePrognosis.ucsf.edu/communication.

Uncertainty

Life expectancy and time to benefit are probabilistic population estimates with inherent uncertainty at the individual level. Despite the uncertainty, population estimates can provide important insights into individual risks and lead to better clinical decisions. The ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk calculator and the CHADS2 atrial fibrillation stroke risk score are examples of population risk estimates that are commonly used to guide individual patient decisions. In fact, much of evidence-based medicine relies on applying uncertain population estimates to individual patients to target treatments to individuals that are most likely to be beneficial. Thus, despite the uncertainty, using life expectancy and time to benefit can lead to better patient outcomes more often than if we ignore life expectancy and time to benefit.

Addressing and communicating uncertainty is a core competency in palliative medicine. Best practices include normalizing the uncertainty, resetting expectations and acknowledging emotions around uncertainty.28 Finally, the inherent uncertainty in current estimates of life expectancy and time to benefit suggests that patient preferences should be given substantial deference when making prevention decisions in older adults.

Applying the Framework During An Annual Medicare Wellness Visit

Mr. A is a 75 year old gentleman who has hypertension (blood pressure 135/75 on fosinopril and chlorthalidone), hyperlipidemia (on Simvastatin) and diabetes (last Hemoglobin A1c 7.2 on glipizide and metformin), chronic obstructive lung disease and painful osteoarthritis. He no longer smokes but has difficulty walking several blocks and bathing independently. He rates his overall health as good and he has not been hospitalized in the past year. He is wondering whether he should be screened for colorectal cancer. Further, he is wondering whether he can stop one of his medicines.

Step 1: Determine the patient’s life expectancy

Using published general mortality indexes for older adults from a systematic review, we identify the Schonberg and Lee indexes as appropriate for this patient. Using the web calculators for these indexes at www.ePrognosis.com, we find that the Schonberg index estimates that the patient has a 5 year mortality risk of 59% whereas the Lee index estimates that the patient has a 4 year mortality risk of 45%. Since the median life expectancy is the time to 50% mortality risk, these indexes suggest that this patient’s life expectancy is approximately 5 years.

Step 2a: Determine the time to benefit for colorectal cancer screening

Our recent studies suggest that for colorectal cancer screening, the time to benefit for an absolute risk reduction of 1 death prevented for 1000 persons screened is approximately 10 years. Since the time to benefit exceeds the patient’s life expectancy, it is unlikely that he would benefit from colorectal cancer screening. Thus, this patient should be advised that colorectal cancer screening is more likely to harm than help and that he would likely be best served by focusing on other health concerns such as his osteoarthritis or hypertension.

Step 2b: Determine the time to benefit for blood pressure control

The ADVANCE study suggests the benefits of more intensive blood pressure control in older patients with diabetes first appear at 12 months, with full benefit at approximately 33 months.29 Given Mr A’s life expectancy of 5 years, continuing more intensive blood pressure control is likely to decrease his mortality risk and would be recommended.

Step 2c: Determine the time to benefit for lipid control

The time to benefit for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with hyperlipidemia vary from 1.5 years to 5 years, depending on the population studied. (see Table 1) Given Mr A’s life expectancy of 5 years, he has a reasonable chance of benefiting from hyperlipidemia treatment. The decision to continue or stop his simvastatin depends primarily on how much he wants to decrease his medication burden.

Step 2d: Determine the time to benefit for glycemic control

The American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for the Care of Older Patients with Diabetes suggests limited benefit with lowering Hemoglobin A1c to <8% for patients with life expectancy <10 years.12 Given Mr A’s life expectancy of 5 years, it is unlikely that he would benefit from tight glycemic control. Given his desire to eliminate one of his medications, decreasing or discontinuing glipizide may be a reasonable recommendation.

Prevention, Treatment and Symptom-Oriented Care

Treatment for many chronic asymptomatic conditions in older adults also has immediate risks and delayed benefits and should be viewed similarly to prevention. For example, treatment for hypertension can quickly lead to orthostatic hypotension and falls but decreased cardiovascular outcomes occur many months or years later. Glycemic treatment for diabetes can cause immediate hypoglycemia, with decreased vascular complications seen many years in the future. Whenever an intervention has immediate risks and delayed benefits, the intervention is preventive and should be targeted to those older adults who have an extended life expectancy that exceeds the time to benefit. Thus, the framework for individualizing prevention applies to the treatment of many diseases in older adults.

In contrast to the treatment of asymptomatic diseases, time to benefit is not a consideration in symptom-oriented care because the harms and benefits both occur immediately. If a patient has a bothersome symptom, any treatment for that symptom could produce immediate benefits, meaning the time to benefit is zero. For example, analgesics for low back pain may cause renal insufficiency, but the benefits of analgesia also occur immediately. Thus, time to benefit and the framework of juxtaposing life expectancy and time to benefit are irrelevant for symptom-oriented care.

Prevention and Palliative Care

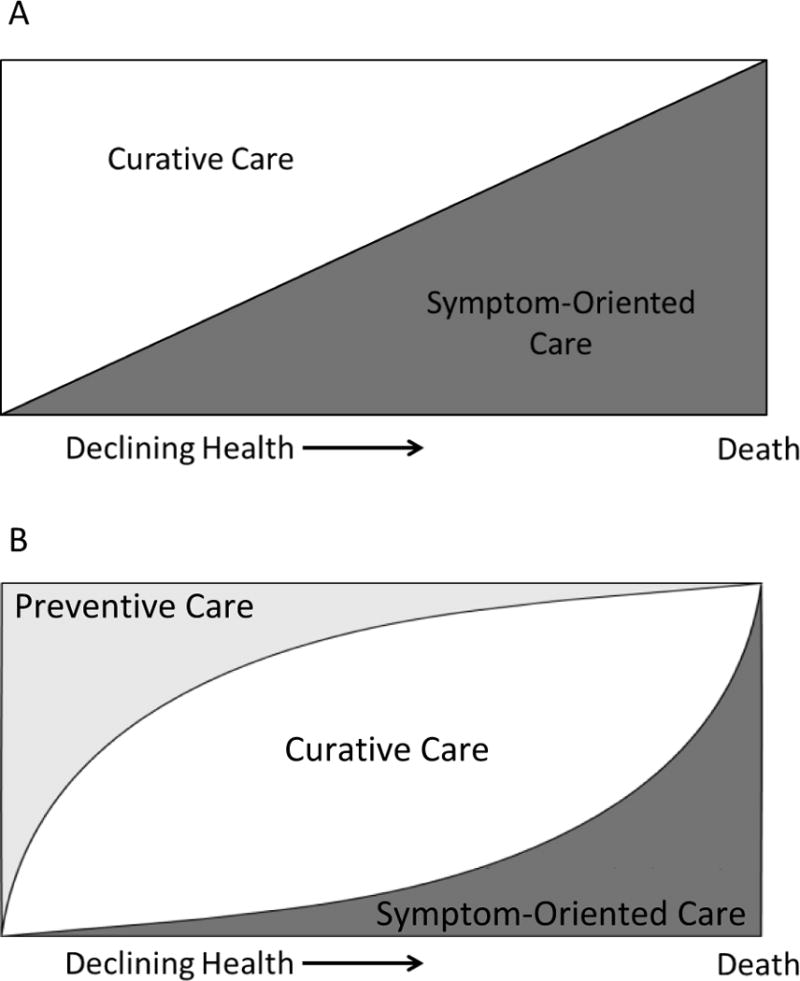

Figure 2A shows one of the current dominant paradigms in palliative care.30 It shows that as patients slowly progress through declining health toward death, the proportion of curative care should decrease and the proportion of symptom-oriented care should increase. Figure 2B shows how we can build on this paradigm to place preventive care in relationship with curative and symptom-oriented care for patients progressing through declining health. When patients are healthy (on the left side of the graph), most of their care should focus on the prevention of future adverse outcomes. As a patient become sicker (in the middle of the graph), the proportion of their care that is focused on prevention should decrease because they have more pressing needs. The care at this stage should focus on diseases that are fixable, such as infections or treatable cancers. As patients approach death (on the right side of the graph), most of their care should focus on symptoms and a palliative approach to care is often most appropriate. Thus, prevention and symptom-oriented palliative care represent the opposite ends of the spectrum of care needed by older adults as their health declines.

Figure 2.

A: Current Paradigm in Palliative Care

B: Incorporating Preventive Care into the Palliative Care Paradigm

Conclusion

Preventing illness through early detection and treatment is a central component of medical care for older adults. However, most prevention exposes patients to immediate risks for the hope of improved health outcomes in the future. Thus, it is critical to the answer to the question, “When will it help?” when individualizing preventive decisions in older adults. While research will continue to improve the accuracy of life expectancy prediction and times to benefit, we are already at the point where many guidelines have moved beyond age and explicitly encourage clinicians to juxtapose life expectancy and time to benefit to maximize benefits and minimize harms of prevention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01AG047897 and V A HSR&D IIR 15-434. Additionally, this work was made possible by the facilities and resources of the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

Sponsor’s Role: Sponsors had no in the conceptualization and preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: SJL and CMK have no conflicts of interests to disclose. Specifically, SJL and CMK have no financial, personal or potential conflicts.

Author Contributions: SJL conceptualized and prepared this manuscript. CMK provided critical revisions to the manuscript. SJL and CMK meet the criteria for authorship stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals. No other authors contributed substantively to this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sei J. Lee, San Francisco VA Medical Center, UCSF Division of Geriatrics, 4150 Clement Street, Bldg 1, Rm 220F, San Francisco, CA 94121, 415-221-4810 x24543, Twitter: @seijlee.

Christine M. Kim, University of California-San Francisco, 1600 Divisadero Street, 3rd Floor, San Francisco, CA 94115, 415-353-9900.

References

- 1.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(1):71–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quick Reference Information: The ABCs of Providing the Annual Wellness Visit. The Medicare Learning Network. 2012 http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/AWV_chart_ICN905706.pdf. Accessed September 5, 2013.

- 3.Lee SJ, Leipzig RM, Walter LC. Incorporating lag time to benefit into prevention decisions for older adults. Jama. 2013;310(24):2609–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes HM, Hayley DC, Alexander GC, Sachs GA. Reconsidering medication appropriateness for patients late in life. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(6):605–609. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yourman LC, Lee SJ, Schonberg MA, Widera EW, Smith AK. Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. Jama. 2012;307(2):182–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. Jama. 2001;285(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SJ, Eng C. Goals of glycemic control in frail older patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1350–1351. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–637. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. The Journal of urology. 2013;190(2):419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 update. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2020–2026. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang V, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Lee SJ. Time to benefit for colorectal cancer screening: survival meta-analysis of flexible sigmoidoscopy trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2015;350:h1662. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van de Glind EM, Willems HC, Eslami S, et al. Estimating the Time to Benefit for Preventive Drugs with the Statistical Process Control Method: An Example with Alendronate. Drugs & aging. 2016;33(5):347–353. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz JB. Primary prevention: do the very elderly require a different approach? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25(3):228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes in Adults Aged >/=75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673–2682. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes HM, Min LC, Yee M, et al. Rationalizing prescribing for older patients with multimorbidity: considering time to benefit. Drugs & aging. 2013;30(9):655–666. doi: 10.1007/s40266-013-0095-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furberg CD, Adams HP, Jr, Applegate WB, et al. Effect of lovastatin on early carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Progression Study (ACAPS) Research Group. Circulation. 1994;90(4):1679–1687. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savarese G, Gotto AM, Jr, Paolillo S, et al. Benefits of statins in elderly subjects without established cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(22):2090–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1708–1717. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel R, Sweeting MJ, Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm in 15-years’ follow-up of the UK endovascular aneurysm repair trial 1 (EVAR trial 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10058):2366–2374. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schonberg MA, Walter LC. Talking about stopping cancer screening-not so easy. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):532–533. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahalt C, Walter LC, Yourman L, Eng C, Perez-Stable EJ, Smith AK. “Knowing is better”: preferences of diverse older adults for discussing prognosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):568–575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1933-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older Adults’ Views and Communication Preferences About Cancer Screening Cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. Jama. 2014;311(13):1336–1347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AK, White DB, Arnold RM. Uncertainty–the other side of prognosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2448–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2007;370(9590):829–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferris FD, Balfour HM, Bowen K, et al. A model to guide patient and family care: based on nationally accepted principles and norms of practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(2):106–123. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beckett N, Peters R, Tuomilehto J, et al. Immediate and late benefits of treating very elderly people with hypertension: results from active treatment extension to Hypertension in the Very Elderly randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2011;344:d7541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):691–700. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2015;385(9986):2477–2484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bibbins-Domingo K. Aspirin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Colorectal Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):836–845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):622–631. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Jama. 2016;315(23):2564–2575. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilt TJ, Harris RP, Qaseem A. Screening for cancer: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):718–725. doi: 10.7326/M14-2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ten Things Clinicians and Patients Should Question. 2015 http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-geriatrics-society/. Accessed July 17. 2017, 2017.