Abstract

Background

Many sepsis survivors develop chronic critical illness (CCI) and are assumed to be immunosuppressed, but there is limited clinical evidence to support this. We sought to determine whether the incidence of secondary infections and immunosuppressive biomarker profiles of patients with CCI differ from those with rapid recovery (RAP) after sepsis.

Methods

This prospective observational study evaluated 88 critically ill patients with sepsis and 20 healthy controls. Cohorts were defined based on clinical trajectory (early death, RAP or CCI) while immunosuppression was clinically determined by the presence of a post-sepsis secondary infection. Serial blood samples were collected for absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC), monocytic HLA-DR (mHLA-DR) expression and plasma soluble programmed death-ligand 1 (sPD-L1) concentrations.

Results

Of the 88 patients with sepsis, three (3%) died within 14 days of sepsis onset, 50 (57%) experienced RAP, and 35 (40%) developed CCI. Compared to RAP patients, CCI patients exhibited a higher incidence and overall number of infections adjusted for hospital length of stay. ALC and mHLA-DR levels were dramatically reduced at the time of sepsis diagnosis when compared to healthy controls, while sPD-L1 concentrations were significantly elevated. There were no differences between RAP and CCI patients in ALC, sPD-L1 or mHLA-DR at time of diagnosis or within 24 hours after sepsis diagnosis. However, in contrast to the RAP group, CCI patients failed to exhibit any trend toward restoration of normal values of ALC, HLA-DR and sPD-L1.

Conclusion

Septic patients demonstrate clinical and biological evidence to suggest they are immunosuppressed at the time of sepsis diagnosis. Those who develop CCI have a greater incidence of secondary infections and persistently aberrant markers of impaired host immunity, although measurements at the time of sepsis onset did not distinguish between subjects with RAP and CCI.

Keywords: shock, inflammation, immunosuppression, catabolism, HLA-DR, soluble programmed death-ligand 1

INTRODUCTION

During recent years, in-hospital mortality to sepsis has substantially declined (1). However, this decrease in mortality has not translated into improved long-term outcomes, nor has it resulted in expedited patient recoveries. Instead, the improvement in short-term survival in the sepsis population has been matched by a growing number of sepsis survivors that develop chronic critical illness (CCI). These patients not only exhibit physical and cognitive deficits that persist beyond their initial hospitalization, but routinely succumb to late complications of sepsis (2, 3). In fact, recent studies demonstrate that over a third of patients diagnosed with sepsis are dead within a year and that another one third have not returned to independent living within 6 months (3). CCI patients are often assumed by the clinician to be chronically immunosuppressed, but clinical data to support this are lacking. To date, there have been no studies that examined whether patients with prolonged recoveries after sepsis demonstrate a greater degree of immune suppression as compared to patients who experience a more rapid recovery.

Host protective immunity has been studied in various patient populations with diverse methodologies being used to assess a patient’s immune status. Some of these methodologies are clinically based, measuring outcomes such as the incidence of secondary infections occurring after admission, while others focus on biological measures including gene expression patterns, biomarker profiles, specific cell counts, and immune functional assays (4–6). Most of these studies, however, fail to link biomarkers of immunosuppression with poor clinical outcomes such as increased long-term mortality and development of nosocomial infections after sepsis. Thus, we attempted to quantify immune suppression in two different populations of sepsis survivors using clinical outcomes, specifically the incidence of post-sepsis secondary infections, as well as biological measures to suggest altered host immunity. We hypothesize that all post-sepsis patients will show clinical and biomarker evidence of immune suppression when compared to healthy age-matched controls. Furthermore, we hypothesize that patients who develop CCI after sepsis will exhibit more severe or persistent alterations in biomarkers to suggest greater impairment in protective immunity, which places these patients at risk for subsequent infections and, perhaps, results in increased long-term mortality. Ultimately, our goal was to determine whether rapid recovery (RAP) from sepsis is associated with biomarker evidence to suggest restoration of host protective immunity, or conversely, whether those with CCI exhibit persistent immune suppression and increased incidence of secondary infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Site and Patients

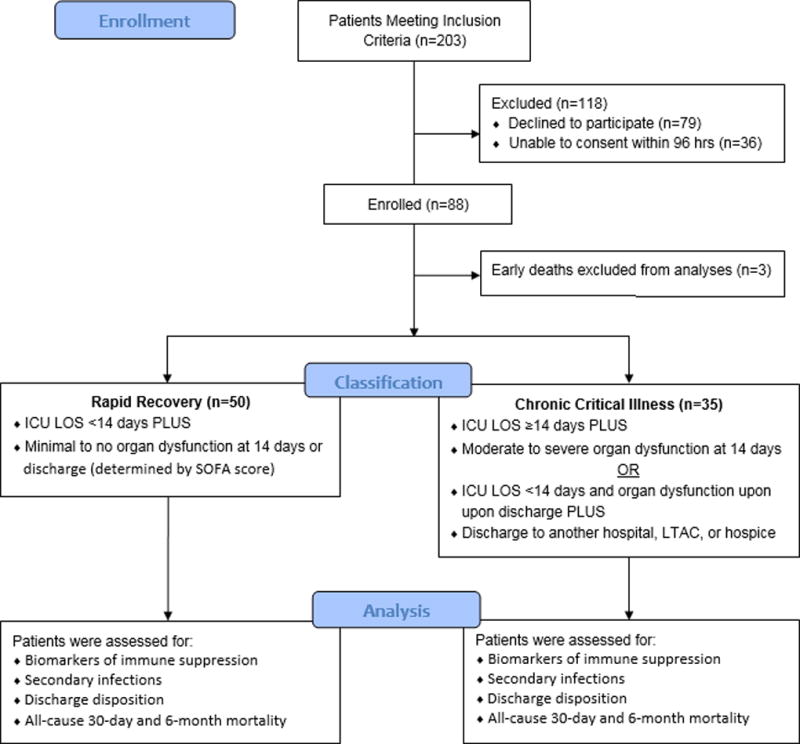

This prospective observational cohort study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Florida (UF) and was performed between April 2016 and April 2017 at UF Health Shands Hospital, a 996-bed academic quaternary-care referral center. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02276417) and conducted by the Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center at UF, whose study design and protocols have been previously published (7). Over the one-year period during which the study was conducted, 85 surgical intensive care unit (ICU) patients were enrolled who were either admitted with, or subsequently developed sepsis during their hospitalization. Patient enrollment and classification is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Outlining Patient Enrollment and Classification.

Screening for sepsis was carried out using the Modified Early Warning Signs-Sepsis Recognition System (MEWS-SRS), which quantifies derangements in vital signs, white blood cell count, and mental status (8). All patients eligible for inclusion in the study were enrolled within 12 hours of sepsis protocol onset on a delayed waiver of consent, which was approved by our Institutional Review Board. If written informed consent could not be obtained from the patient or their legally assigned representative within 96 hours of study enrollment, the patient was removed from the study and all collected biologic samples and clinical data were destroyed. All patients with sepsis were managed using a standardized, evidence-based protocol that emphasizes early goal-directed fluid resuscitation as well as other time-appropriate interventions such as administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Emperic antibiotics were chosen based on current hospital antibiograms in conjunction with the suspected source of infection (9). Antimicrobial therapy was then narrowed based on culture and sensitivity data. If a patient did not improve on this standardized empiric antibiotic regimen, a consult was placed to Infectious Disease for alternative recommendations.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients eligible for participation in the study met the following inclusion criteria: (1) admission to the surgical or trauma ICU; (2) age ≥18 years; (3) clinical diagnosis of sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock with this being the patient’s first septic episode; and (4) entrance into our sepsis clinical management protocol.

Patients were excluded if any of the following were present: (1) refractory shock (i.e. patients expected to die within the first 24 hours); (2) an inability to achieve source control (i.e. irreversible disease states such as unresectable dead bowel); (3) pre-sepsis expected lifespan <3 months; (4) patient/family not committed to aggressive management; (5) severe CHF (NYHA Class IV); (6) Child-Pugh Class C liver disease or pre-liver transplant; (7) known HIV with CD4+ count <200 cells/mm3; (8) organ transplant recipient or use of chronic corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents; (9) pregnancy; (10) institutionalized patients; (11) chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 30 days; (12) severe traumatic brain injury (i.e. evidence of neurological injury on CT scan and a GCS <8); (13) spinal cord injury resulting in permanent sensory and/or motor deficits; or (14) inability to obtain informed consent.

Patient Classification

Patients were diagnosed with sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock using the definitions established by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, and the Surgical Infection Society (SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS) 2001 International Sepsis Definitions Conference (10). CCI was defined as an ICU length of stay (LOS) greater than or equal to 14 days with evidence of persistent organ dysfunction, measured using components of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at 14 days (i.e. cardiovascular SOFA ≥ 1, or score in any other organ system ≥ 2) (11). Patients with an ICU LOS less than 14 days would also qualify for CCI if they were discharged to another hospital, a long-term acute care facility, or to hospice and demonstrated evidence of organ dysfunction at the time of discharge. Those patients experiencing death within 14 days of sepsis onset were excluded from the clinical and biomarker analyses. Any patient who did not meet criteria for CCI or early death was classified as RAP. Since there is no consensus definition for CCI, we focused on combining key elements established by previous definitions reported in the literature, including the requirement for prolonged intensive care and the presence of persistent organ dysfunction. However, our definition was modified to include a more broad classification of organ dysfunction, as previous definitions relied heavily on the presence of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Primary Clinical Outcomes

Primary outcomes included incidence and overall number of secondary infections per patient during the index hospitalization, secondary infections corrected for the time at risk (i.e. secondary infections per 100 hospital person days), discharge disposition, and all-cause 30-day and 6-month mortality. Immunosuppression was determined clinically, by the presence of a secondary infection, since these patients are prima facie immunocompromised. This concept is supported by a recent study, which demonstrated the genomic response of patients who acquire secondary infections after sepsis is consistent with that of immune suppression (6). As previously described, secondary infections were defined as any probable or microbiologically-confirmed bacterial, yeast, fungal, or viral infection requiring treatment with antimicrobials and occurring ≥48 hours after sepsis protocol onset during the index hospitalization (6, 12, 13). Coexisting infections, that is, those occurring within the first 48 hours after sepsis diagnosis, were not included, since these were felt to represent simultaneous infections independent of the primary sepsis event. Viral titers were not routinely measured, therefore subclinical viral infections are not presented in this analysis.

Selection of Biomarkers

In routine laboratory analyses, absolute lymphocyte counts (ALCs) have been used as an indicator of immune suppression since lower ALCs are linked to the reactivation of latent viruses as well as recurrent bacterial infections requiring hospital admission (14–16). In addition, mHLA-DR expression on CD14+ blood monocytes has been found to correlate with mortality in severe sepsis patients and susceptibility to secondary infections in neurosurgical patients (17, 18). Elevated levels of sPD-L1, the soluble form of the transmembrane receptor PD-L1, has been associated with decreased activation of T cells and T cell apoptosis in cancer (19, 20).

Sample Collection and Laboratory Analyses

Serial blood samples were collected from hospitalized septic patients at 12 hours, one, four, seven, 14, 21, and 28 days after sepsis protocol initiation. Blood samples were also collected from twenty healthy controls, which were age-, race- and gender-matched to the sepsis population. For septic patients, complete blood counts with differential were performed by the Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratories at UF Health Shands Hospital for determination of absolute lymphocyte counts (ALCs). Plasma levels of sPD-L1 were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Monocyte Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR (mHLA-DR) expression was determined using fluorescence quantification with the Quantibrite™ HLA-DR/Monocyte system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorescent beads were used to quantitate the number of binding antibodies per CD14+ cell. Fluorescence was determined using a Becton-Dickinson LSR II™ Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as frequency and percentage for categorical variables, or mean and standard deviation, or median and 25th/75th percentiles for continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used for comparison of categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The number of secondary infections per 100 hospital person days and number of secondary infections per patient were modeled using a Poisson model with overdispersion. Six month survival and incidence of secondary infection curves were plotted for both the CCI and RAP groups using the Kaplan Meier method.

The effect of time and group on laboratory results were modeled using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with Poisson variance assumption and log link, which incorporated time, group, and the interaction of the two variables into the model. The fitted mean functions are plotted with 95% pointwise confidence bands. The means of the laboratory results for each group at distinct time points have been added to all plots.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models using HLA-DR, sPDL1, and ALC at 24 hours after sepsis onset were constructed to predict clinical trajectory (CCI and early death versus RAP), as well as the incidence of secondary infection. Adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve values (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported. All significance tests were two-sided, with p-value ≤0.05 considered statistically significant. These statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R 3.4.0 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Sepsis Characteristics

Demographics of the overall cohort and the individual RAP and CCI groups appear in Table 1. Of the 88 patients enrolled, three died within the first 14 days of sepsis onset (3%), 35 patients progressed to CCI (40%), and 50 patients experienced RAP (57%). Between the CCI and RAP groups, there were no significant differences in patient age, race, number of comorbidities, or hospital transfer status. However, patients with CCI showed greater physiological derangement within 24 hours after sepsis onset, as indicated by their APACHE II scores (p<0.001). Only 40% of the entire cohort was admitted for either sepsis or an infectious-related complication, while the majority of surgical patients enrolled in the study were admitted for non-infectious etiologies, a planned surgical procedure, or severe traumatic injury.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics by Clinical Trajectory

| Demographics | Entire Cohort* (n=88) |

Rapid Recovery (n=50) |

CCI (n=35) |

P-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 48 (54.6) | 23 (46.0) | 23 (65.7) | 0.082 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 57.8 (16.2) | 55.5 (15.9) | 59.7 (16.5) | 0.153 |

| Age ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 34 (38.6) | 16 (32.0) | 15 (42.9) | 0.363 |

| BMI, median (25th, 75th) | 30.4 (25.3, 36.2) | 30.4 (25.5, 36.9) | 29.6 (24.9, 36.2) | 0.751 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.841 | |||

| Caucasian (White) | 78 (88.6) | 43 (86.0) | 32 (91.4) | |

| African American | 9 (10.2) | 6 (12.0) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 3.91 (2.90) | 3.44 (2.86) | 4.47 (2.96) | 0.069 |

| APACHE II score (24 hrs), mean (SD) | 17.5 (7.6) | 14.6 (6.04) | 20.9 (8.07) | <0.001 |

| ICU LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 7 (3, 20.5) | 4 (2, 7) | 21 (17, 37) | |

| Hospital LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 17 (9, 29) | 10.5 (7, 16) | 32 (26, 44) | |

| Inter-facility hospital transfer, n (%) | 38 (43.2) | 18 (36.0) | 18 (51.4) | 0.185 |

| Admission Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.288 | |||

| Infection-related | 35 (39.8) | 24 (48.0) | 11 (31.4) | |

| Non-infectious complication | 38 (43.2) | 20 (40.0) | 15 (42.9) | |

| Planned surgery or procedure | 9 (10.2) | 4 (8.0) | 5 (14.3) | |

| Trauma | 6 (6.8) | 2 (4.0) | 4 (11.4) |

Definitions of Abbreviations: CCI = chronic critical illness; SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; APACHE II = acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay

Patients experiencing early death (n=3), within 14 days of their hospitalization, are excluded from this and subsequent analyses

p-value comparing the CCI and rapid recovery groups

Sepsis characteristics of the two cohorts of interest, that is, RAP and CCI, appear in Table 2. In comparison to patients who experience RAP, CCI patients were twice as likely to develop hospital-acquired sepsis (sepsis onset ≥48 hours after hospital admission) and three times as likely to present in septic shock (p<0.001 and p=0.008, respectively). With regards to primary sepsis diagnosis, CCI patients demonstrated a predisposition towards pneumonia, whereas RAP patients were more likely to present with necrotizing soft tissue infections or urosepsis. Notably, the incidence of intra-abdominal infections did not significantly differ between groups, nor did the number of surgical source control procedures performed.

Table 2.

Sepsis Characteristics by Clinical Trajectory

| Sepsis Characteristics | Rapid Recovery (n=50) |

CCI (n=35) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital-acquired sepsis*, n (%) | 15 (30.0) | 25 (71.4) | <0.001 |

| Primary Sepsis Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.005 | ||

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | 20 (40) | 17 (48.6) | 0.507 |

| Pneumonia | 4 (8) | 8 (22.9) | 0.065 |

| NSTI | 13 (26) | 2 (5.7) | 0.020 |

| Urosepsis | 8 (16) | 1 (2.9) | 0.075 |

| Surgical site infection | 4 (8) | 2 (5.7) | 1 |

| Empyema | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | 0.167 |

| CLABSI | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.412 |

| Bacteremia | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.412 |

| Mediastinitis | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 0.412 |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Sepsis source control procedure, n (%) | 36 (72.0) | 19 (54.3) | 0.110 |

| Sepsis Severity, n (%) | 0.013 | ||

| Sepsis | 21 (42) | 7 (20) | 0.038 |

| Severe Sepsis | 23 (46) | 15 (42.9) | 0.827 |

| Septic Shock | 6 (12) | 13 (37.1) | 0.008 |

Definitions of Abbreviations: CCI = chronic critical illness; NSTI = necrotizing soft tissue infection; CLABSI = central line-associated blood stream infection

Hospital-acquired sepsis refers to sepsis onset ≥48 hours after admission to any hospital, including outside hospitals with subsequent inter-facility transfers

Patient Outcomes and Clinical Evidence of Immune Suppression

Patient outcomes are presented in Table 3. A striking number of CCI patients acquired a secondary infection (25 patients, or 71%), with a mean onset of 12 days. In contrast, only a small percentage (6%) of RAP patients developed a secondary infection (p<0.001). Within the CCI cohort, the mean number of secondary infections per patient was 1.11, in comparison to 0.06 in the RAP group (p<0.001). Even after adjusting for time at risk, (i.e., hospital length of stay), the difference in the incidence of secondary infections between CCI and RAP groups remained statistically significant (p<0.001). The most commonly observed secondary infection was pneumonia (n=11), followed by intra-abdominal infections (n=10), surgical site infections (n=6), urinary tract infections (n=4), and reactivation of latent viruses (n=4). Of the intra-abdominal infections, the most common etiologies were intra-abdominal abscesses, anastomotic leaks, and Clostridium difficile colitis. While the etiology of secondary infections did not significantly differ between groups, there was a trend towards increasing viral, fungal, and surgical site infections in the CCI group, without a single patient in the RAP group experiencing one of these infections (Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary Infections, Discharge Disposition, and Mortality By Clinical Trajectory

| Secondary Infection Characteristics | Rapid Recovery (n=50) |

CCI (n=35) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of secondary infections*, mean per patient (SD) | 0.06 (0.24) | 1.11 (0.90) | <0.001 |

| Number of patients with secondary infections, n (%) | 3 (6.0) | 25 (71.4) | <0.001 |

| Total number of secondary infections | 3 | 39 | |

| Secondary infections per 100 hospital person days, mean (SD) | 0.31 (1.29) | 3.47 (3.24) | <0.001 |

| Type of secondary infection, n (%) | |||

| Intra-abdominal | 1 (33.3) | 9 (23.1) | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (66.7) | 9 (23.1) | 0.163 |

| UTI | 0 (0) | 4 (10.3) | 1 |

| NSTI | 0 (0) | 2 (5.1) | 1 |

| Surgical Site Infection | 0 (0) | 6 (15.4) | 1 |

| Empyema | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 |

| Bacteremia / CLABSI | 0 (0) | 2 (5.1) | 1 |

| Viral Infections | 0 (0) | 4 (10.3) | 1 |

| Fungal/Yeast Infections | 0 (0) | 2 (5.1) | 1 |

| Days to secondary infection from sepsis onset, mean (SD) | 13.0 (17.3) | 12.3 (11.2) | 0.352 |

| Discharge disposition†, n (%) | |||

| “Good” disposition | 46 (92.0) | 10 (32.3) | <0.001 |

| Home | 13 (26.0) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Home healthcare services | 31 (62.0) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Rehab | 2 (4.0) | 2 (6.5) | |

| “Poor” disposition | 4 (8.0) | 21 (67.7) | <0.001 |

| Long term acute care facility | 0 (0) | 10 (32.3) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 4 (8.0) | 4 (12.9) | |

| Another Hospital | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | |

| Hospice | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | |

| Death | 0 (0) | 4 (12.9) | |

| 30-Day mortality‡, n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (11.4) | 0.015 |

| 6-Month mortality‡, n (%) | 2 (4.0) | 9 (25.7) | 0.002 |

Definitions of Abbreviations: CCI = chronic critical illness; SD = standard deviation; UTI = urinary tract infection; NSTI = necrotizing soft tissue infection; CLABSI = central line-associated bloodstream infection

Secondary infection refers to any additional viral, fungal, yeast, or bacterial infection occurring ≥48 hours after sepsis onset and requiring antimicrobial treatment during the index hospitalization

To detect significant differences in discharge disposition between groups, CCI patients with an ICU length of stay ≤ 14 days (n=4) were excluded since these patients qualified for CCI based on discharge disposition.

30-day and 6-month mortality include deaths from all causes within the 30 to 180 day period following sepsis protocol initiation, respectively.

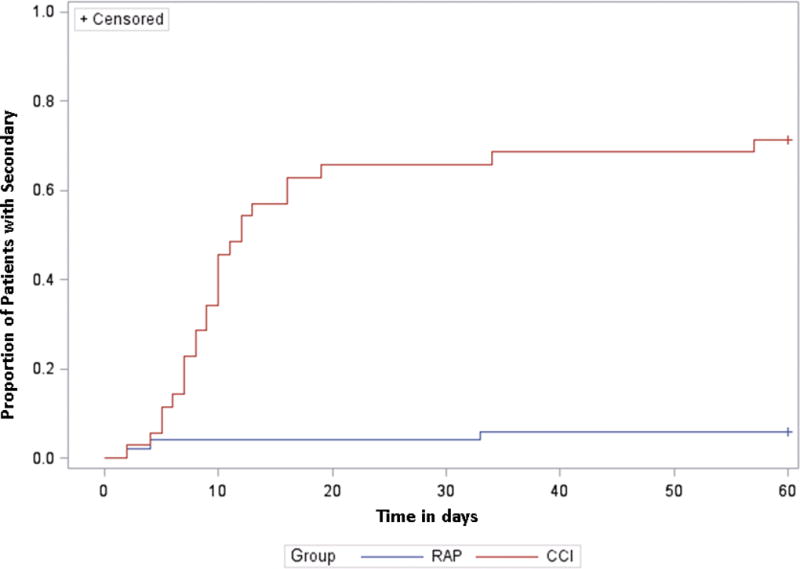

Notably, most RAP patients who developed a secondary infection were likely to present with these infections within the first 10 days of sepsis onset, but thereafter, the incidence of secondary infections slowed, reaching a plateau. Conversely, in the CCI group, there was a continued sharp rise in the incidence of secondary infections until approximately 20 days after sepsis diagnosis, at which point the curve stabilized (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Incidence of Secondary Infections Over Time in Patients with Chronic Critical Illness (CCI) versus Rapid Recovery (RAP).

Kaplan-Meier curves show cumulative incidence of secondary infections in the CCI and RAP groups over a 60-day period.

In addition to the frequency of secondary infections, discharge dispositions between the two groups were examined. To determine significant differences between groups, the four patients who met the criteria for CCI based on their discharge disposition and an ICU length of stay < 14 days were excluded. After excluding these individuals, we found that CCI patients were still more likely to be discharged to “poor” discharge dispositions, as compared to patients with RAP, the majority of which (92%) were discharged to home or to a rehabilitation facility.

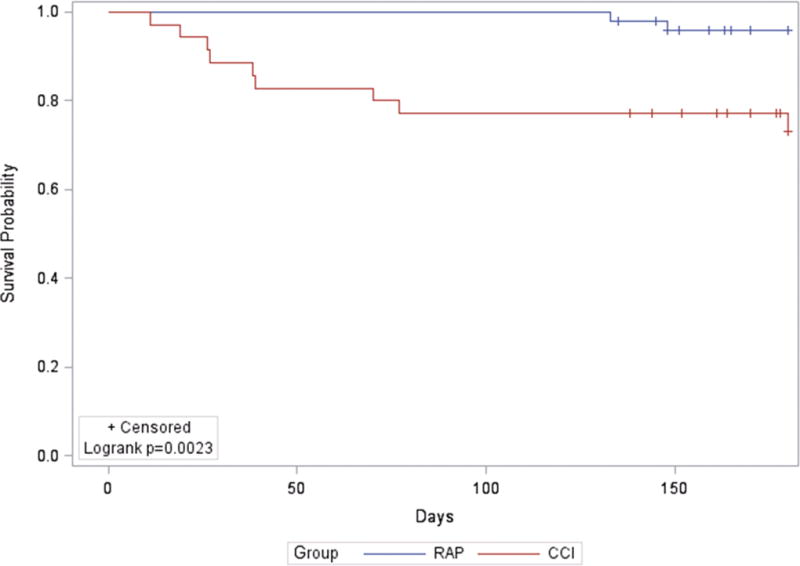

Not only were CCI patients more likely to require a higher level of care due to presumed functional impairment, but these patients also exhibited a statistically significant increase in 30-day and 6 month mortality (p=0.015 and p=0.002, respectively) (Table 3 & Figure 3). A striking 26% of CCI patients had succumbed within 6 months after their initial sepsis event, with 11% dying within the first 30 days. Comparatively, 96% of RAP patients were alive 6 months.

Figure 3. Six Month Mortality Analysis in Patients with Chronic Critical Illness (CCI) versus Rapid Recovery (RAP).

The Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrates cumulative survival rate over 6 months in CCI versus RAP patients. Patients who have yet to reach 6 months after their initial sepsis event are censored and are denoted with tick marks.

Characteristics of Patients with Secondary Infections

A subgroup analysis was performed to examine differences in the characteristics of patients who developed secondary infections and those who did not (Table 4). On average, patients who acquired secondary infections after sepsis were older (62 ± 16 years versus 55 ± 16 years, p=0.044), had more comorbidities (4.9 versus 3.4, p=0.025), and were more likely to present in septic shock, demonstrating greater measurable organ dysfunction within 24 hours (APACHE II scores of 21 ± 8 versus 15 ± 7, p=0.003). Furthermore, these patients had significantly longer hospital and ICU lengths of stay (p<0.001), and were more likely to present with intra-abdominal sepsis as their primary sepsis diagnosis, whereas patients who did not develop secondary infections showed a predilection for necrotizing soft tissue infections.

Table 4.

Demographic Data for Patients with and without Secondary Infections

| Demographics | Patients without secondary infections (n=57) |

Patients with secondary infections (n=28) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 29 (50.9) | 17 (60.7) | 0.489 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 55.0 (16.2) | 61.9 (15.5) | 0.044 |

| Age ≥ 65 years, n (%) | 18 (31.6) | 13 (46.4) | 0.232 |

| BMI, median (25th, 75th) | 30.6 (25.3, 36.9) | 29.5 (25.3, 33.9) | 0.861 |

| Race, n (%) | 1 | ||

| Caucasian (White) | 50 (87.7) | 25 (89.3) | |

| African American | 6 (10.5) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 3.39 (2.74) | 4.85 (3.10) | 0.025 |

| APACHE II score (24 hrs), mean (SD) | 15.4 (6.8) | 20.9 (7.8) | 0.003 |

| ICU LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 5 (3, 9) | 20 (15.5, 32.5) | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOS, median (25th, 75th) | 12 (8, 21) | 29 (20, 47) | <0.001 |

| Inter-facility hospital transfer, n (%) | 20 (37.7) | 16 (50.0) | 0.365 |

| Sepsis severity, n (%) | 0.018 | ||

| Sepsis | 23 (40.4) | 5 (17.9) | 0.050 |

| Severe Sepsis | 26 (45.6) | 12 (42.9) | 1 |

| Septic Shock | 8 (14.0) | 11 (39.3) | 0.013 |

| Primary sepsis diagnosis, n (%) | 0.092 | ||

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | 20 (35.1) | 17 (60.7) | 0.036 |

| Pneumonia | 8 (14.0) | 4 (14.3) | 1 |

| NSTI | 13 (22.8) | 2 (7.1) | 0.128 |

| Surgical site infection | 5 (8.8) | 1 (3.6) | 0.659 |

| Empyema | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.6) | 1 |

| CLABSI | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Bacteremia | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 0.329 |

| Mediastinitis | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 0.329 |

| Urosepsis | 8 (14.0) | 1 (3.6) | 0.260 |

| Other | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 |

Definitions of Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index; APACHE II = acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay; NSTI = necrotizing soft tissue infection; CLABSI = central line-associated blood stream infection

Commonly identified etiologies of secondary infections within the surgical sepsis population included gram-negative bacteria (34.5%), followed by gram-positive bacteria (25.6%), fungi (15.5%), and viral infections (5.2%). Causative organisms were often either resistant or opportunisitic pathogens such as Candida spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Causative Pathogens Involved in Secondary Infections*

| Type of Pathogen | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Candida spp. | 9 (20.9) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 5 (11.6) |

| Enterobacter spp. | 4 (9.3) |

| Klebsiella spp. | 4 (9.3) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 (9.3) |

| Escherichia coli | 3 (7) |

| Herpes simplex virus (HSV) | 3 (7) |

| Streptococcus viridans | 3 (7) |

| Clostridium diffficile | 2 (4.7) |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 1 (2.3) |

| Corynbacterium striatum | 1 (2.3) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 1 (2.3) |

| Morganella morganii | 1 (2.3) |

| Providencia rettgeri | 1 (2.3) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltiphilia | 1 (2.3) |

Secondary infection refers to any additional viral, fungal, yeast, or bacterial infection occurring ≥48 hours after sepsis onset and requiring antimicrobial treatment during the index hospitalization

Biological Evidence of Immune Suppression

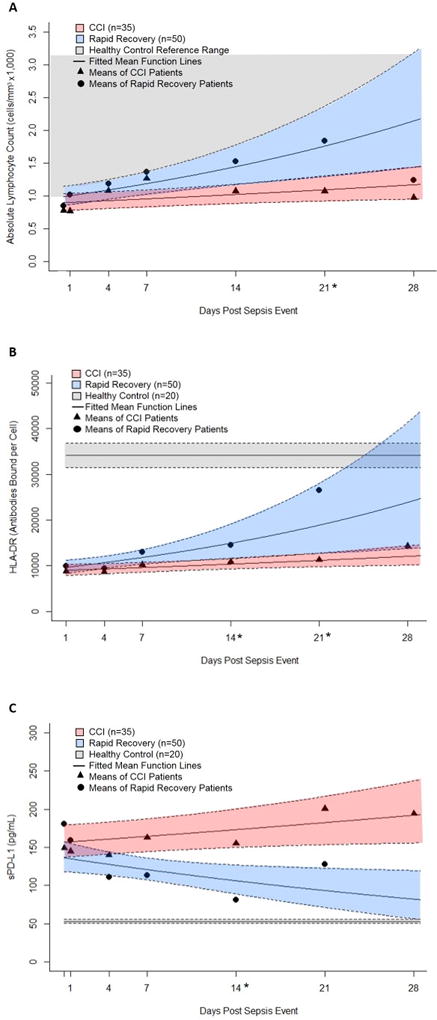

All sepsis patients demonstrated biomarker evidence to suggest impaired host immunity, with CCI patients displaying the greatest alterations in these biomarkers. In comparison to matched healthy controls, sepsis patients had lower ALCs, particularly within the first four days post sepsis event. Based on GEE model results, there were significant estimated differences in the slope for ALC over time between the CCI and RAP groups (p=0.036), with RAP patients demonstrating accelerated restoration of their ALCs (Figure 4A). In contrast, CCI patients experienced a more gradual increase in cell count, with ALCs often remaining suppressed out to 28 days (Figure 4A). HLA-DR expression was also dramatically reduced in all sepsis patients at every time point when compared to healthy controls (Figure 4B). GEE model analyses, used to examine the CCI and RAP groups, revealed that HLA-DR, over time, was significantly lower in CCI patients. Likewise, significant differences in HLA-DR were found at 14 and 21 days when examining means between groups at individual time points using non-parametric rank sum tests (p<0.05). Concentrations of sPD-L1 were markedly elevated in the sepsis population when compared to healthy controls. Among sepsis survivors, RAP patients demonstrated a decline of sPD-L1 towards normal range while sPD-L1 remained persistently elevated in CCI patients (p<0.05) (Figure 4C). Subanalysis of patients admitted with sepsis versus those who acquired sepsis after another injury such as trauma or a planned surgery, revealed no significant differences between the two groups with respect to the above biomarkers.

Figure 4. Biomarkers of Immunosuppression Over Time in Patients with Chronic Critical Illness (CCI) versus Rapid Recovery (RAP).

Blood samples were collected at 0.5, 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after sepsis protocol onset from patients who developed sepsis in the surgical ICU and these patients were prospectively followed for development of CCI versus RAP. Absolute Lymphocyte counts (ALC) (panel A), HLA-DR expression on CD14+ monocytes (panel B), and plasma concentrations of sPD-L1 (panel C) were used to measure immune status in these patients. The biomarker means of CCI (▲) and RAP (●) patients are reported at each time point. Using general estimating equations with Poisson variance assumption and log link, fitted mean function lines were plotted for the CCI and RAP groups with 95% confidence interval bands (RAP designated in blue and CCI designated in red). The estimated differences in slopes between CCI and RAP groups over time were significant for ALC (p=0.036) and sPD-L1 (−0.03, p=0.004) at 0.05 level and for HLA-DR (p=0.069) at 0.1 level, indicating ALC and HLA-DR were increasing and sPD-L1 was decreasing over time faster for RAP group. Non-parametric rank tests were also performed to determine significant differences at individual times, which are denoted along the x-axis with an asterisk (*). For ALC, the normal range for healthy controls are reported according to our institution’s reference range. With regards to HLA-DR and sPD-L1, values from healthy controls are reported as the mean with standard error bands.

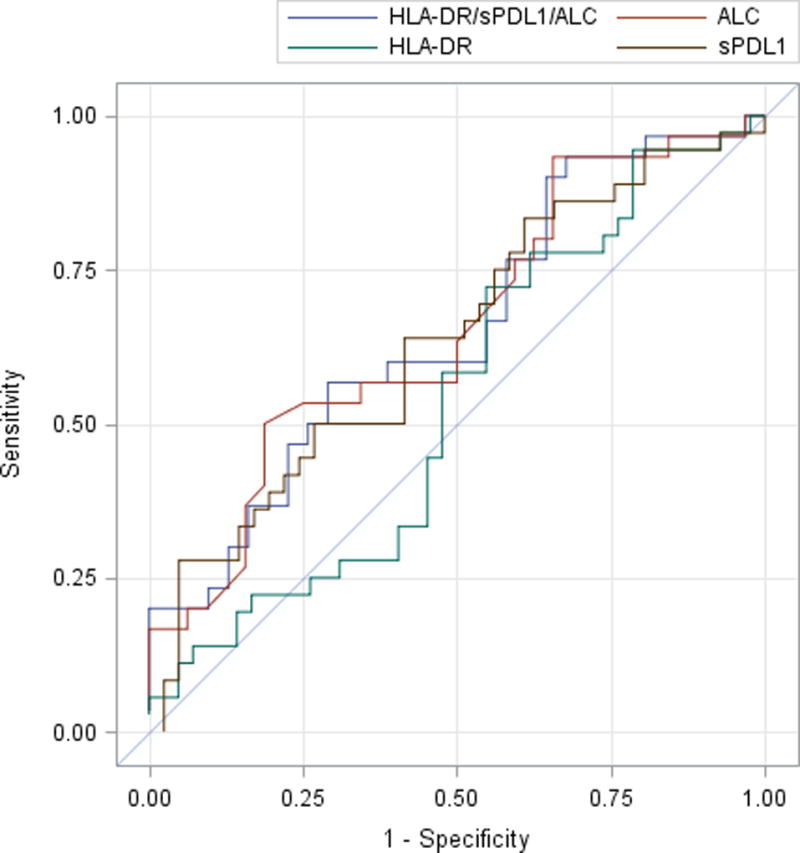

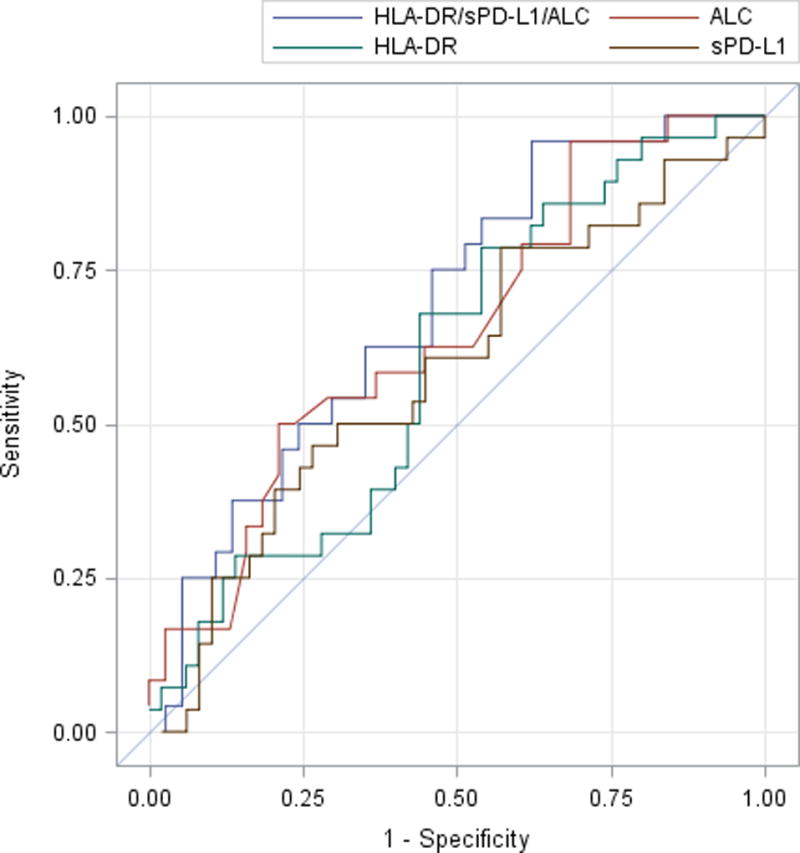

Univariate logistic regression model analyses revealed that all biomarkers were relaticting the development of CCI at 24 hours with AUCs of 0.536 (95% CI 0.405–0.666), 0.637 (95% CI 0.512–0.762), and 0.654 (95% CI 0.516–0.792) for HLA-DR, sPD-L1, and ALC, respectively (Figure 5A). When combined, the multivariate model yielded an AUC of 0.652 (95% CI 0.513–0.790). None of the unadjusted or adjusted odds ratios were significant. Similar results were observed for the outcome of secondary infections (Figure 5B). Clinical scoring, using patient APACHE II scores obtained at 24 hours, only slightly improved the performance of the prediction models with AUCs of 0.748 (95% CI 0.638–0.858) and 0.699 (95% CI 0.583–0.815) for predicting CCI and secondary infections, respectively.

Figure 5. Biomarker Prediction Modeling for the Development of Chronic Critical Illness (CCI) and Secondary Infections.

Odds ratios were derived using logistic regression models both individually and including all listed variables, simultaneously. All prediction models were created using data obtained 24 hours after sepsis management protocol onset. Receiver operating curves were constructed with the relative AUCs of each curve being reflected in the corresponding table. Aside from the absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), the other biomarkers (HLA-DR and sPD-L1) were relatively poor at predicting CCI and secondary infections.

| A. Model for CCI | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) for CCI |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) for CCI |

AUC (95% CI) for CCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 0.536 (0.405, 0.666) |

| sPD-L1 | 1.005 (0.998, 1.011) | 1.001 (0.993, 1.009) | 0.637 (0.512, 0.762) |

| ALC | 0.342 (0.109, 1.074) | 0.331 (0.102, 1.073) | 0.654 (0.516, 0.792) |

| HLA-DR/sPD-L1/ALC | ---------- | ---------- | 0.652 (0.513, 0.790) |

| B. Model for Secondary Infection |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) for Secondary Infection |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) for Secondary Infection |

AUC (95% CI) for Secondary Infection |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DR | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 1.000 (1.000, 1.000) | 0.6014 (0.4727, 0.7302) |

| sPD-L1 | 1.002 (0.996, 1.008) | 1.003 (0.995, 1.012) | 0.5904 (0.4553, 0.7255) |

| ALC | 0.239 (0.061, 0.933) | 0.257 (0.065, 1.009) | 0.6497 (0.5094, 0.7900) |

| HLA-DR/sPD-L1/ALC | ---------- | ---------- | 0.6881 (0.5542, 0.8219) |

DISCUSSION

An increasing number of patients survive the exaggerated inflammatory phase of their initial septic insult, but often develop protracted hospital courses and ongoing organ dysfunction. These chronically critically ill patients are presumed to enter a prolonged immunosuppressive state, during which they are at increased risk for secondary infections and resulting mortality (21, 22). This immunosuppressive state may occur as a result of chronic antigenic stimulation and T-cell exhaustion, but requires further investigation (23). While there is sufficient evidence to confirm immune suppression in those who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure, there is a relative paucity of data surrounding immune suppression in sepsis survivors, particularly those who develop CCI (24). Rather, most studies, to date, have focused on characterizing the immunological phenotype of sepsis survivors as compared to non-survivors, with the goal of identifying biomarkers to predict mortality to sepsis.

Our study shows that all sepsis survivors, regardless of their clinical trajectory, exhibit impairment in host immunity, with biomarker alterations to suggest ongoing immunosuppression persisting out to a month after the initial septic insult. This immune suppression is manifested, clinically, by increased susceptibility to secondary infections during the index hospitalization after sepsis onset, with one-third of sepsis survivors (33%) developing a secondary infection. Strikingly, the nosocomial infection rate observed in post-sepsis patients is almost three times higher than the current reported rate of health-care associated infections observed in adults and children in ICUs across the United States (13%) (25). However, it is important to note that CCI patients accounted for the majority of subjects (89%) with secondary infections. One may assume this is due to their prolonged hospital and ICU lengths of stay, which increase their exposure to highly virulent and resistant pathogens, and hence their risk of nosocomial infections. However, we found that differences between the mean secondary infections occurring in the CCI versus RAP population, when adjusted for hospital days, remained statistically significant (3.5 secondary infections per 100 hospital person days versus 0.3, p<0.001), suggesting an alternative explanation for the increased incidence of nosocomial infections in these patients.

One plausible explanation for the increased susceptibility to secondary infections in sepsis survivors is ongoing immune dysfunction, which is consistent with our previously proposed syndrome of persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism (PICS) (26–29). In our current study, we show that all septic patients demonstrate reduced ALCs and HLA-DR expression and increased sPD-L1 concentrations, which persist for weeks to months after sepsis onset. Compared to healthy individuals, the ALCs of CCI patients remained suppressed over time, while ALCs increased dramatically in the RAP group. Similarly, expression of HLA-DR in the septic population, measured by antibodies bound per cell, was one-third to one-half of that seen in healthy controls, suggesting greater monocyte deactivation in these patients (30). There is also evidence to support a blunted adaptive immune response in septic patients, as indicated by their increased plasma concentrations of sPD-L1, which ultimately leads to the down-regulation of T-cells (31). Of the sepsis population, those who developed CCI had significantly higher sPD-L1 concentrations and lower HLA-DR expression, most notable around 2 weeks after sepsis onset. These findings support a greater and a more prolonged impairment of both innate and adaptive immunity in the CCI group.

The immune suppression observed in the CCI group is not only reflected by deviations in quantifiable biomarkers such as the ALC, sPD-L1 concentrations, and HLA-DR expression, but is also clinically supported by these patients’ increased susceptibility to secondary infections and all-cause mortality at 6 months. The pairing of physiological biomarkers of immunosuppression with clinical data to support immune suppression makes this study unique, since previous studies have often looked at these entities in isolation of one another, or have looked at the relationship between these biomarkers and outcomes such as in-hospital mortality or multiple organ failure. Therefore, this is the first study to link the physiological and clinical data to support immune suppression with clinical outcomes such as chronic critical illness and secondary infections. With the research paradigm evolving to a bench-to-bedside-to-bench format, studies of this nature which will be increasingly relevant to ensure the applicability of future translational research.

With regards to the broader context of this research, our study challenges previous immune deficiency thresholds used to predict the risk of nosocomial sepsis. These thresholds include: (1) neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count < 500 cells/mm3), (2) monocyte deactivation (HLA-DR expression <30% or <8000 – 12000 molecules per cell), (3) lymphopenia (ALC < 1,000 cells/mm3), and (4) hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG < 500 mg/dl) (32). Refuting any of the above has significant clinical implications since several of these thresholds are used as criteria for enrollment into current clinical trials. One ongoing clinical trial is evaluating immunomodulatory therapies, specifically GM-CSF, to decrease ICU acquired infections (NCT02361528). In this clinical trial, HLA-DR expression levels of <8,000 molecules per cell at day 3 of sepsis onset are used to determine sepsis-associated immunosuppression. However, this is problematic because our data suggests that a single measurement of HLA-DR, especially at the time of sepsis diagnosis, is a poor early predictor of outcomes such as the development of CCI and secondary infections, which represent the clinical manifestations of underlying immune suppression. In fact, HLA-DR levels of patients who rapidly recover versus those who progress to CCI and are at increased risk for nosocomial infections cannot be reliably distinguished until 7–14 days after sepsis onset, which is significantly longer than the collection time during which HLA-DR is measured in current clinical trials. Taken together, these findings raise the question as to whether these biomarkers of immune suppression can be used early in a patient’s clinical course after sepsis to stratify patients into presumed clinical trajectories. Our data suggests that biomarkers obtained within the first 12–24 hours will not aid in early prediction of CCI or secondary infections for this surgical sepsis cohort, although the utility of these biomarkers at later time points, or in sepsis with other origins, has yet to be determined. It is clear that additional studies will be required to assess the robustness of current biomarker thresholds being used to enroll sepsis patients in clinical trials, which are assumed to be linked to poor clinical outcomes.

Although these biomarkers could not distinguish between RAP and CCI patients at early time points, specifically within the first 24 hours of sepsis diagnosis, there are significant differences in the overall trends between CCI and RAP patients, which mirrors their clinical trajectories. The divergence of these two patient populations, with respect to their clinical outcomes and immunologic phenotype, demonstrates there are key underlying differences present in host protective immunity. Whether these differences supersede a patient’s sepsis diagnosis or arise as a product of sepsis, has yet to be determined. However, the similarities in patient demographics and biomarkers, at baseline, suggests perhaps that these immunologic changes are triggered by sepsis, with more persistent immunologic alterations coinciding with increasing sepsis severity. Still, this hypothesis remains speculative, and further studies which include functional assays will be needed to fully assess the immunologic phenotype of these patient populations.

There are a number of limitations to this study that require comment. First, our study is limited to sepsis occurring within the surgical ICU population so the results may not be applicable when extrapolated to the overall community. Additionally, surgical patients are prone to recurrent inflammatory insults, which may lead to persistent immune dysregulation, predisposing them to develop CCI with resulting immune suppression. This study is also centered around the inpatient experience, and does not include post-discharge data following the index hospitalization so infections occurring after hospital discharge are not accounted for in this analysis. Blood sampling is also confined to the inpatient setting, making it difficult to obtain samples at later time points, particularly in the RAP group since many of these patients were discharged. Undoubtedly, further long-term studies that involve collection of blood samples during later time points with a larger study cohort, including possible outpatient follow up, may be required to reliably determine long-term differences in immune status between groups. Another limitation worth noting is the selection of the control population for this study. Septic ICU patients were compared to healthy age, race, and gender-matched controls rather than non-infected ICU patients, since there was concern that admission to the ICU for non-sepsis events such as severe traumatic injury generates a highly heterogeneous group of patients with varying organ injury that would likely minimize detectable differences in the experimental group. Finally, the recently established sepsis-3 definitions were not used to classify patients in the study since the use of qSOFA and operationalizing sepsis-3 remains controversial, and because CMS continues to use the old definitions, complicating the ability of physician-scientists to fully embrace sepsis-3.

Despite these limitations, we were able to conclude the following: 1) Post-sepsis patients, for the most part, are immunosuppressed; and 2) In comparison to those who rapidly recover, patients who develop CCI experience greater and more prolonged impairment of host protective immunity, as evidenced by their increased susceptibility to secondary infections, lower ALCs and mHLA-DR expression, and marked elevations in sPD-L1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all clinicians and support staff of the Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center at UF Shands Health engaged in ongoing sepsis and inflammation research. We specifically acknowledge Bridget Baisden, Jillianne Brakenridge, Ruth Davis, Jennifer Lanz, and Ashley McCray for their invaluable work and contributions to this project.

Supported, in part, by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants: R01 GM-040586 and R01 GM-104481 (LLM), R01 GM-113945 (PAE), and P50 GM-111152 (FAM, SCB, LLM, PAE, BAB, AMM, AB) awarded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). In addition, this work was supported, in part, by a postgraduate training grant T32 GM-008721 (JAS, JCM, TJL) in burns, trauma, and perioperative injury by NIGMS.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: JAS, TJM, SLR, JCM and TJL contributed extensively to the drafting of the manuscript, revision of its content, and approval of the manuscript in its final form. TOB, ZW, GLG, BAB contributed to the conception and design of the project as well as data analysis. RU, MLS, and DCN contributed to data analysis and interpretation. AMM, AB, PAE, LLM, FAM, and SB contributed to data analysis, interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, revision of its content, and approval of the manuscript in its final form.

References

- 1.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(13):1308–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yende S, Austin S, Rhodes A, Finfer S, Opal S, Thompson T, Bozza FA, LaRosa SP, Ranieri VM, Angus DC. Long-Term Quality of Life Among Survivors of Severe Sepsis: Analyses of Two International Trials. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(8):1461–1467. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budde K, Matz M, Durr M, Glander P. Biomarkers of over-immunosuppression. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(2):316–322. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser DR, Dombrovskiy VY, Vogel TR. Infectious complications after vehicular trauma in the United States. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2011;12(4):291–296. doi: 10.1089/sur.2010.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Vught LA, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Spitoni C, Scicluna BP, Wiewel MA, Horn J, Schultz MJ, Nurnberg P, Bonten MJ, Cremer OL, van der Poll T. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Attributable Mortality of Secondary Infections in the Intensive Care Unit After Admission for Sepsis. JAMA. 2016;315(14):1469–1479. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loftus TJ, Mira JC, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ghita GL, Wang Z, Stortz JA, Brumback BA, Bihorac A, Segal MS, Anton SD, Leeuwenburgh C, Mohr AM, Efron PA, Moldawer LL, Moore FA, Brakenridge SC. Sepsis and Critical Illness Research Center investigators: protocols and standard operating procedures for a prospective cohort study of sepsis in critically ill surgical patients. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015136. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croft CA, Moore FA, Efron PA, Marker PS, Gabrielli A, Westhoff LS, Lottenberg L, Jordan J, Klink V, Sailors RM, McKinley BA. Computer versus paper system for recognition and management of sepsis in surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(2):311–317. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000121. discussion 318–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitousis K, Moore LJ, Hall J, Moore FA, Pass S. Evaluation of empiric antibiotic use in surgical sepsis. Am J Surg. 2010;200(6):776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.001. discussion 782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G. Sccm/Esicm/Accp/Ats/Sis: 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Melot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286(14):1754–1758. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calandra T, Cohen J. International Sepsis Forum Definition of Infection in the ICUCC: The international sepsis forum consensus conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(7):1538–1548. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000168253.91200.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, Horan TC, Hughes JM. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16(3):128–140. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong DSY, Bonten MJM, Spitoni C, Verduyn Lunel FM, Frencken JF, Horn J, Schultz MJ, van der Poll T, Klein Klouwenberg PMC, Cremer OL. Epidemiology of Multiple Herpes Viremia in Previously Immunocompetent Patients With Septic Shock. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(9):1204–1210. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 2015;313(10):1055–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walton AH, Muenzer JT, Rasche D, Boomer JS, Sato B, Brownstein BH, Pachot A, Brooks TL, Deych E, Shannon WD, Green JM, Storch GA, Hotchkiss RS. Reactivation of multiple viruses in patients with sepsis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e98819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asadullah K, Woiciechowsky C, Docke WD, Egerer K, Kox WJ, Vogel S, Sterry W, Volk HD. Very low monocytic HLA-DR expression indicates high risk of infection--immunomonitoring for patients after neurosurgery and patients during high dose steroid therapy. Eur J Emerg Med. 1995;2(4):184–190. doi: 10.1097/00063110-199512000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ditschkowski M, Kreuzfelder E, Rebmann V, Ferencik S, Majetschak M, Schmid EN, Obertacke U, Hirche H, Schade UF, Grosse-Wilde H. HLA-DR expression and soluble HLA-DR levels in septic patients after trauma. Ann Surg. 1999;229(2):246–254. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199902000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, Roche PC, Lu J, Zhu G, Tamada K, Lennon VA, Celis E, Chen L. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norde WJ, Maas F, Hobo W, Korman A, Quigley M, Kester MG, Hebeda K, Falkenburg JH, Schaap N, de Witte TM, van der Voort R, Dolstra H. PD-1/PD-L1 interactions contribute to functional T-cell impairment in patients who relapse with cancer after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5111–5122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(12):862–874. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otto GP, Sossdorf M, Claus RA, Rodel J, Menge K, Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC. The late phase of sepsis is characterized by an increased microbiological burden and death rate. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):R183. doi: 10.1186/cc10332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):260–268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD, 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Srivastava A, Swanson PE, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306(23):2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, Cardo DM. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(2):160–166. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentile LF, Cuenca AG, Efron PA, Ang D, Bihorac A, McKinley BA, Moldawer LL, Moore FA. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(6):1491–1501. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318256e000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mira JC, Gentile LF, Mathias BJ, Efron PA, Brakenridge SC, Mohr AM, Moore FA, Moldawer LL. Sepsis Pathophysiology, Chronic Critical Illness, and Persistent Inflammation-Immunosuppression and Catabolism Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2016 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal MD, Moore FA. Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolism: Evolution of Multiple Organ Dysfunction. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2016;17(2):167–172. doi: 10.1089/sur.2015.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanzant EL, Lopez CM, Ozrazgat-Baslanti T, Ungaro R, Davis R, Cuenca AG, Gentile LF, Nacionales DC, Cuenca AL, Bihorac A, Leeuwenburgh C, Lanz J, Baker HV, McKinley B, Moldawer LL, Moore FA, Efron PA. Persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome after severe blunt trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(1):21–29. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182ab1ab5. discussion 29–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volk HD, Reinke P, Krausch D, Zuckermann H, Asadullah K, Muller JM, Docke WD, Kox WJ. Monocyte deactivation--rationale for a new therapeutic strategy in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(Suppl 4):S474–481. doi: 10.1007/BF01743727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frigola X, Inman BA, Lohse CM, Krco CJ, Cheville JC, Thompson RH, Leibovich B, Blute ML, Dong H, Kwon ED. Identification of a soluble form of B7-H1 that retains immunosuppressive activity and is associated with aggressive renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(7):1915–1923. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carcillo JA. Critical Illness Stress-induced Immune Suppression. In: Vincent J-L, editor. Intensive Care Medicine: Annual Update 2007. Springer Science & Business Media; 2007. [Google Scholar]