Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine whether higher cumulative proton pump inhibitor (PPI) exposure is associated with increased dementia risk.

DESIGN

Prospective population-based cohort study.

SETTING

Kaiser Permanente Washington, an integrated health-care delivery system, Seattle, Washington

PARTICIPANTS

3,484 participants aged 65 and older without dementia at study entry.

MEASUREMENTS

Participants were screened for dementia every 2 years and those screening positive underwent extensive evaluation. Dementia outcomes were determined using standard diagnostic criteria. Time-varying PPI exposure was defined from computerized pharmacy data and consisted of the total standardized daily doses (TSDDs) dispensed to an individual in the prior 10 years. We also assessed duration of use. Multivariable Cox regression was used to estimate the association between PPI exposure and time to dementia or Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

RESULTS

Over a mean follow-up of 7.5 years, 827 participants (23.7%) developed dementia (670 with possible or probable AD). PPI exposure was not associated with risk of dementia (p=0.66) or AD (p=0.77). For dementia, the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing 365, 1095, and 1825 TSDDs of PPI exposure (representing a quantity of PPI equivalent in amount to 1, 3, and 5 years of daily use) to no use were 0.87 (95% CI, 0.65–1.18); 0.99 (0.75–1.30); and 1.13 (0.82–1.56). Duration of PPI use was also not associated with dementia outcomes.

CONCLUSION

PPI use was not associated with increased dementia risk, even for people with high cumulative exposure. While there are other safety concerns with long-term PPI use, results from our study do not support that patients and clinicians should avoid these medications because of concern over dementia risk.

Keywords: dementia, Alzheimer disease, pharmacoepidemiology, cohort study, proton pump inhibitor, aged

INTRODUCTION

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are widely used to treat acid-related gastrointestinal disorders, including gastroesophageal reflux disease. In 2011, approximately one in five older adults in the US reported using a PPI,[1] and these medications are frequently used long-term.[2] PPIs are overprescribed across the spectrum of care, including primary care, inpatient and nursing home settings,[3,4] with estimates that up to 40% of use is not supported by evidence.[5] PPIs are often prescribed inappropriately for stress ulcer prevention in hospitalized patients and continued after discharge.[6]

For many years, PPIs were thought to have minimal toxicity; however, mounting evidence suggests these agents may be associated with negative health consequences including fractures and kidney disease.[7,8] Especially concerning is the potential link between PPI use and increased dementia risk.[9–11] Researchers from Germany first reported an association between PPI use and dementia in a multicenter cohort study of older primary care patients.[9] Subsequently, two studies using administrative data also reported increased dementia risk with PPI use;[10,11] however, relying on administrative data to identify incident dementia cases may be problematic. Importantly, prior studies were unable to control for potential confounders such as exercise, obesity, functional status and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. Despite these limitations, there is some biological plausibility for these findings. PPIs may accelerate senescence in human endothelial cells and affect amyloid metabolism in cellular and animal models of AD although data are conflicting for the latter.[12–14] PPIs have also been postulated to increase dementia risk by contributing to vitamin B12 deficiency,[9,10] which can occur with long-term gastric acid suppression.[15]

Given the enormous public health implications of widespread PPI use, a better understanding of potential cognitive risks of cumulative PPI use is urgently needed. Unanswered questions remain regarding the impact of dose and duration of use beyond 18 months. Longer PPI exposure may be particularly relevant for a condition with a long latent period such as dementia. We used data from a prospective cohort study with research-quality dementia diagnoses, detailed electronic pharmacy data, and extensive capture of participant health, functional, and other confounding characteristics to evaluate the association between cumulative PPI use over a long exposure window and the risk for dementia or Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We hypothesized that higher cumulative use would be associated with increased risk.

METHODS

Design, Study Setting, and Participants

The Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study is a population-based prospective cohort study conducted within Kaiser Permanente Washington, an integrated health-care delivery system in the northwest US. This healthcare delivery system was previously known as Group Health and was acquired by Kaiser Permanente in 2017. Study methods have been described in detail elsewhere.[16] Participants aged 65 years and older without dementia were randomly sampled from Seattle-area members. Participants were enrolled during three waves: the original cohort between 1994 and 1996 (n=2581), the expansion cohort between 2000 and 2003 (n=811), and continuous enrollment beginning in 2004. Participants were assessed at study entry and at two-year intervals to evaluate cognitive function and collect information about demographic characteristics, medical history, health behaviors, and functional measures. The ACT study has an excellent index of completeness of follow-up[17] of greater than 95%. These analyses were limited to participants that had at least one follow-up visit (4221 subjects as of April 30, 2014). To ensure adequate information about long-term medication exposure, we excluded participants with less than 10 years of health plan membership prior to ACT enrollment (n=737), leaving a sample of 3484 for this analysis. Study procedures are approved by our Human Subjects Review Committee, and participants provide written informed consent

Assessment of Dementia and AD

Participants were screened for dementia at study entry and every two years using the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI).[18] Those screening positive on the CASI (score ≤85) underwent a standardized diagnostic evaluation which included neuropsychological testing.[16] A multidisciplinary committee assigned diagnoses of dementia and AD using research criteria.[19,20] Date of dementia onset was assigned as the midpoint between the ACT study visit triggering the dementia evaluation and the preceding visit. Participants with new onset dementia underwent one follow-up examination to confirm the diagnosis.

Proton Pump Inhibitor Medication Use

PPI use was ascertained from computerized pharmacy data that included drug name, strength, route of administration, date dispensed, and amount dispensed. PPIs first became available as prescription medications in 1989 and some as over-the-counter (OTC) in late 2003. The health plan continued to cover prescription PPIs that were also available OTC. Information was collected at interviews every 2 years about self-reported current medication use, including use of OTC medications. We supplemented prescription records with self-reported non-prescription medications to increase capture of OTC PPI usage.

Our primary exposure measure was cumulative dose measured as follows. We first calculated the total PPI dose for each prescription by multiplying the medication strength by the number of tablets dispensed. We then calculated the number of standardized daily doses (SDD) for each prescription by dividing the total PPI dose by the minimum effective dose per day for the product (omeprazole 20 mg; pantoprozole 40 mg; esomeprazole 20 mg; lansoprazole 30 mg; and rabeprazole 20 mg). After converting these dispensings to SDD, we then determined each participant’s time-varying cumulative PPI exposure – measured as total standardized daily dose (TSDD) – at each point in time during study follow-up.[21,22] We did this by summing the SDD for all of a participant’s PPI pharmacy fills within the past 10 years after excluding dispensings in the most recent 1 year, to address bias that might result from altered use of PPIs during the prodromal phase of dementia.[23] Supplementary Figure S1 illustrates how the time-varying exposure window was defined. The reason we limited exposure measurement to 10-year windows, rather than looking at all available data for each individual, was to ensure a common exposure assessment period for all individuals being compared at each point during follow-up. Otherwise, differential error in exposure capture could lead to biased results. Also, a 10-year exposure period was thought to be sufficiently long to ensure reasonably good capture of cumulative exposure levels across individuals. To incorporate OTC use into our exposure measure, we added 100 SDDs to the TSDD from visits where participants reported current use of OTC PPIs (only 16 visits involving 15 participants).[24]

Because the precise aspect of PPI exposure that may impact dementia risk is not known, we also examined two additional exposure constructs using the same 10-year window approach: total duration of use and longest duration of continuous use. We measured duration by first determining episodes of PPI use for each person in our sample on the basis of prescription fill dates, days supply of the dispensings, an assumed compliance factor (80%) for adhering to the prescribed regimen, and a stockpiling algorithm to account for the fact that people may refill prescriptions early (i.e., before the prior fill’s runout date) adapted from prior work.[25,26] Then at each point in time during study follow-up for each participant, we computed the total duration of all the person’s distinct episodes of PPI use within the current 10-year exposure window after excluding dispensings in the most recent 1 year, as well as their longest duration of continuous use (i.e. episode of use) in that window.

Covariates

Based on a literature review, we selected covariates that may be potential confounders of the association between PPI use and dementia risk including demographic characteristics, health behaviors, comorbidities, functional measures, and medications.[7,9,10] Information about covariates came from standardized questionnaires administered at each study visit and from health plan electronic databases. Demographic characteristics included age at study entry, sex, and years of education. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.[27] Participants were asked about smoking, self-rated health and exercise. Regular exercise was defined as ≥ 15 minutes of activity at least three times a week.[28] We ascertained presence of medication-treated hypertension and diabetes mellitus (computerized pharmacy data), history of stroke (self-report or diagnosis codes from electronic databases), and coronary heart disease (self-report of prior myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, angioplasty, or angina). Depressive symptoms were assessed using the short version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.[29] Number of hospitalizations (from electronic databases) in the past two years was included as a proxy of health status. Functional measures included gait speed (10 foot timed walk) and difficulty with activities of daily living (ADLs; self-report).[30] Use of anticholinergic medications and NSAIDs was ascertained from computerized pharmacy data (represented as TSDDs).[21,31] APOE genotype was categorized as presence or absence of any ε4 alleles.[32,33]

Statistical Analyses

We used multivariable Cox regression models, with participant’s age as the time scale, to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between PPI use and incident all-cause dementia or possible or probable AD. We modeled exposure with cubic splines.[34] Participants were followed until the earliest of dementia onset, GH disenrollment, or last study visit before April 30, 2014. For the AD analysis, we censored participants at time of onset of any non-AD dementia. Separate models were estimated for each outcome (all-cause dementia and possible or probable AD) and exposure measure (TSDD, total duration, longest duration of continuous use) pair. For each, we present HR and 95% CI estimates from a minimally adjusted model that only included age at study entry and study cohort, as well as a primary model that included additional adjustment for sex, years of education, BMI, current smoking, self-rated health, regular exercise, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, coronary heart disease, depressive symptoms, gait speed, difficulties with ADLs, number of recent hospitalizations, and cumulative exposure (TSDDs) to NSAIDs and anticholinergic medications. We included time-varying measures for coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes and medication use measured over the same time-varying 10 year window as PPI use. Values from the ACT baseline visit were used for all other covariates. We excluded 152 (4.4%) participants with missing covariate information from all model estimates. We assessed proportional hazards using Schoenfeld residuals.[35]

Sensitivity Analyses

We performed several sensitivity analyses. Interaction terms were used to estimate separate HRs for PPI exposure according to sex. We considered models additionally adjusted for the Charlson comorbidity index[36] and APOE genotype, as well as models for the outcome of probable AD only.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R, version 3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

The median age of participants at study entry was 74, 90% were white, and 59% were female. People using PPIs prior to study enrollment were more likely to be female, have difficulty with ADLs, and have higher overall comorbidity (Table 1). Omeprazole was the most common PPI used during the entire exposure period, including the 10 years prior to study entry through the end of follow-up (Supplementary Table S1). During this time, 1061 (30.5%) participants had at least 1 dispensing for a PPI. Of PPI users, 460 (43.4%) used between 1 and 180 TSDDs, 211 (19.9%) used between 180 and 730 TSDDs, 159 (15.0%) used between 730 and 1825 TSDDs, and 231 (21.8%) used greater than 1825 TSDDs. Of those 231, 167 (72.3%) individuals had periods of continuous use lasting more than 3 years.

Table 1.

| No PPI Use | PPI use | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| N=3,082 | N=402 | |

| Age, median (IQR) | 74 (70, 80) | 75 (70, 81) |

| Female | 1809 (58.7) | 260 (64.7) |

| White | 2782 (90.3) | 354 (88.3) |

| Years of education, median (IQR) | 14 (12, 16) | 16 (12, 18) |

| Obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2) | 766 (25.4) | 106 (27.5) |

| Current smoker | 158 (5.1) | 6(1.5) |

| Fair/poor self-rated health | 453 (14.7) | 79 (19.7) |

| Regular exercisec | 2,226 (72.4) | 259 (64.9) |

| Treated hypertensiond | 1,831 (59.4) | 308 (76.6) |

| Treated diabetese | 250 (8.1) | 41 (10.2) |

| Strokef | 183 (5.9) | 40 (10.0) |

| Coronary heart diseaseg | 539 (17.5) | 93 (23.1) |

| Depression (CES-D score ≥ 10)h | 276 (9.1) | 54 (14.0) |

| Slow gait speed (<0.6m/sec) | 265 (8.6) | 48 (12.2) |

| Difficulty with ≥ 1 ADLs | 639 (20.8) | 123 (30.9) |

| Hospital admission within 2 yrs | 500(16.2) | 111 (27.6) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | ||

| 0 | 2,113 (68.6) | 216 (53.7) |

| 1 | 510 (16.5) | 82 (20.4) |

| 2+ | 459 (14.9) | 104 (25.9) |

| Use of any NSAIDsi | 2,243 (72.8) | 307 (76.4) |

| Use of any anticholinergic medicationsi | 2,367 (76.8) | 337 (83.8) |

| At least 1 APOE ε4 allele | 700 (25.8) | 80 (24.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; ADLs, Activities of Daily Living; NSAIDs, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs; IQR, interquartile range; PPI, Proton Pump Inhibitor.

Data are presented as N (%) unless otherwise noted. Column percentages based on non-missing data. Missing data for each variable: years of education (n=1), BMI (n=78), depression (n=57), smoking (n=8), regular exercise (n=9), self-rated health (n=7), slow gait speed (n=26), ADL (n=17) and APOE ε4 allele (n=435).

Use of PPIs was determined in the 10 years prior to baseline.

≥ 15 minutes of activity at least three times a week

Two or more fills in computerized pharmacy data for antihypertensive medications in 12 months prior to ACT study entry.

Two or more fills in computerized pharmacy data for insulin or oral diabetic medications in 12 months prior to ACT study entry.

Self-report or codes 430.X, 431.X, 432.X, 434.X, 436.X and 438.X from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

Self-reported history of heart attack, angina, angioplasty, or coronary artery bypass surgery

Score of 10 or greater on the modified version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) questionnaire.

From computerized pharmacy data in the 10 years prior to ACT study entry.

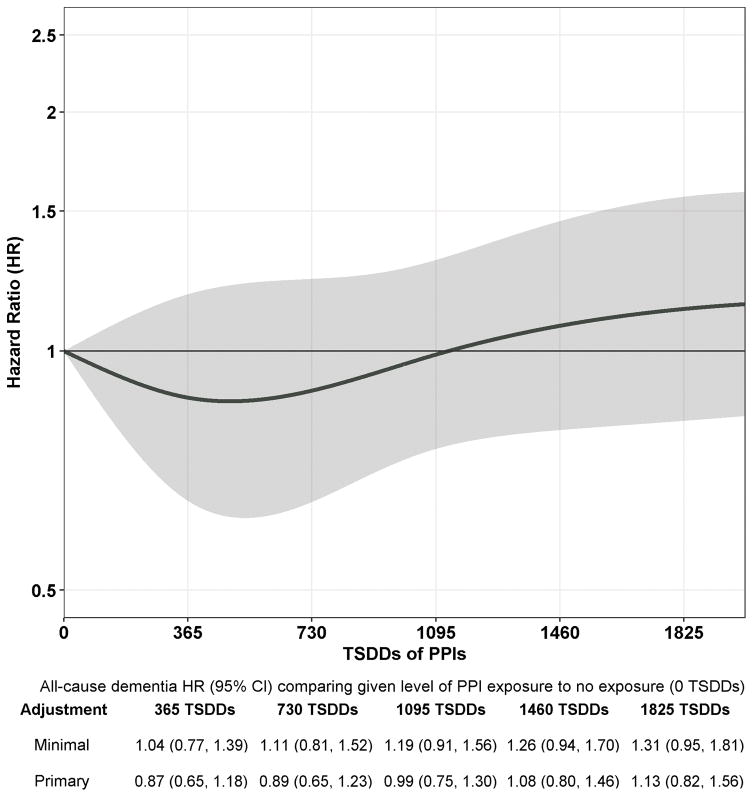

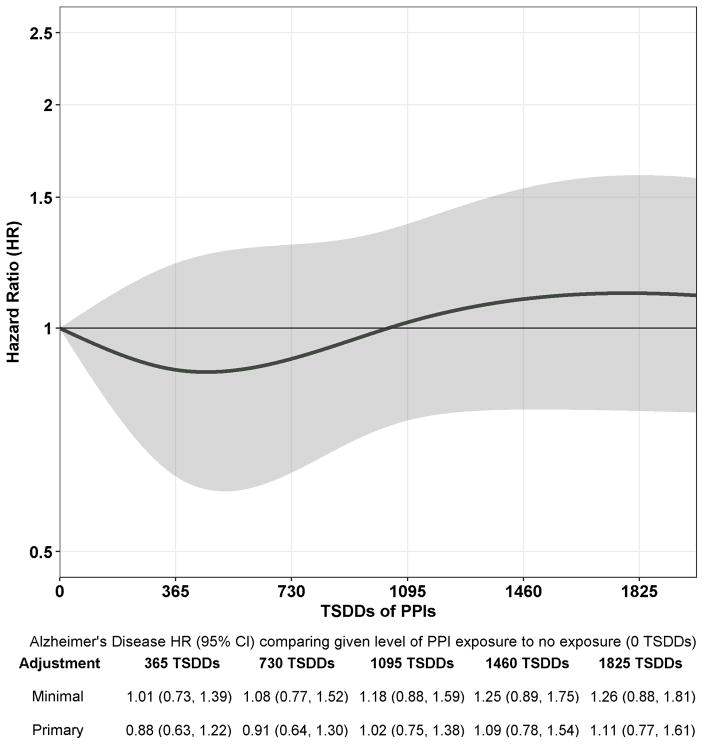

Participants had a mean (SD) follow-up of 7.5 (5.0) years and accrued 26,012 person-years of follow-up time. Of 3484 participants, 827 (23.7%) developed dementia of which 670 developed possible or probable AD. Figure 1 shows the estimated HR and 95% CI for dementia for each level of exposure relative to no cumulative exposure (0 TSDDs). Overall, PPI use was not related to dementia risk (p=0.66). When examining specific levels of exposure compared to no use, the adjusted HRs for 365, 1095, and 1825 TSDDs (representing a quantity of PPI equivalent in amount to 1, 3, and 5 years of daily use) were 0.87 (95% CI, 0.65–1.18); 0.99 (95% CI, 0.75–1.30); and 1.13 (95% CI, 0.82–1.56) (Figure 1). Results were similar for AD (Figure 2; p=0.77). We found no evidence of non-proportional hazards for estimates of interest.

Figure 1.

Association between Cumulative Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Incident Dementia. The curve corresponds to estimated adjusted HRs for dementia comparing a given level of proton pump inhibitor exposure (on x-axis) to no exposure (0 TSDDs). Shading corresponds to 95% confidence intervals for the adjusted HR estimates. Y-axis uses a log scale but with corresponding HRs denoted. The minimally adjusted estimates (shown only in the table below the plot) are from a model adjusted only for age and study cohort. The estimates from the primary adjusted model (shown both in the table and the plot) are adjusted for age, study cohort, sex, education, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, stroke, coronary heart disease, body mass index, exercise, self-rated health, depression, gait speed, difficulties with activities of daily living, hospitalizations, and cumulative exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and anticholinergic medications. 152 (4.4%) participants with missing covariate information were excluded from all model estimates. TSDD, Total Standardized Daily Dose

Figure 2.

Association between Cumulative Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease. The curve corresponds to estimated adjusted HRs for Alzheimer’s disease comparing a given level of proton pump inhibitor exposure (on x-axis) to no exposure (0 TSDDs). Shading corresponds to 95% confidence intervals for the adjusted HR estimates. Y-axis uses a log scale but with corresponding HRs denoted. The minimally adjusted estimates (shown only in the table below the plot) are from a model adjusted only for age and study cohort. The estimates from the primary adjusted model (shown both in the table and the plot) are adjusted for age, study cohort, sex, education, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, stroke, coronary heart disease, body mass index, exercise, self-rated health, depression, gait speed, difficulties with activities of daily living, hospitalizations, and cumulative exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and anticholinergic medications. 152 (4.4%) participants with missing covariate information were excluded from all model estimates. TSDD, Total Standardized Daily Dose

We also did not find a significant association between dementia outcomes and PPI use when we examined total duration of use (Supplementary Figures S2A and S2B) or longest duration of continuous use (Supplementary Figures S3A and S3B). Results were similar after adjusting for comorbidity index or APOE genotype (Supplementary Table S2). Effect modification by sex was not detected (p = 0.14 for dementia, p=0.15 for AD).

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort study of older adults, we found that PPI use was not associated with dementia or AD risk. This finding was consistent across a wide range of cumulative doses, including high levels of cumulative PPI exposure. For example, people with high PPI exposure (1825 TSDDs) had a HR of 1.13 (95% CI, 0.82–1.56) for developing dementia compared to those having no use. In addition to cumulative dose, we also failed to find an association between duration of PPI use, including both total duration and the longest duration of continuous use. No prior study had as detailed information about medication exposure over an extended period of time to examine this important issue; therefore, this study fills an important clinical and research gap. Findings were robust in a variety of sensitivity analyses.

Our findings are in contrast with results from longitudinal studies conducted in Germany and Taiwan.[9–11] In a prospective, population based study of 3327 patients from primary care clinics in Germany, PPI use was associated with an increased risk for dementia (HR 1.38; 1.04–1.83) and AD (HR 1.44; 1.01–2.06).[9] These same investigators reported a similar magnitude of risk for PPI use and dementia (HR 1.44; 1.36–1.52) in a cohort study using administrative data from a large German health insurer involving 73,679 participants.[10] These studies differed in the method for dementia ascertainment (case finding[9] versus claims data[10]) and exposure assessment (self-report[9] versus claims data[10]). Using time-varying methods, both studies examined risk for dementia over the 18 months following ascertainment of PPI use. Lastly, PPI use was associated with increased dementia risk (HR 1.22, 1.05–1.42) in a cohort study using administrative data from the Taiwan’s National Insurance Research Database.[11]

Several aspects of our study may explain the discrepancy in our findings compared with these prior studies. Compared with the German studies, we examined medication use over a much longer exposure period, which may be a more biologically plausible timeframe for assessing this relationship given the long latent period of dementia.[37] Another difference was our study’s ability to capture cumulative PPI use and duration and examine dementia risk across a wide range of exposure levels rather than relying on a categorical measure of use versus no use.[9,10] In our study, participants underwent regular cognitive screening and standardized dementia evaluations to detect incident dementia, and thus we are able to avoid biases such as underrecognition or under-coding of dementia that are inherent to studies based on administrative claims data.[38,39] For example, people with unrecognized dementia have more frequent contact with the healthcare system up to 3 years prior to the diagnosis which may lead to greater opportunities to receive prescriptions for PPIs.[40] Alternatively, people being treated with PPIs for active symptoms may have more frequent contact with the healthcare system, possibly resulting in a higher likelihood of dementia being recognized and coded. Both of these scenarios can lead to differential misclassification of outcomes. Lastly, we adjusted for many confounders that have not been available in prior studies including exercise, BMI, functional measures and NSAID use.

Prior studies finding a PPI-dementia link postulated that vitamin B12 deficiency may be one mechanism underlying this increased risk.[9,10] By decreasing gastric acidity, PPIs may decrease B12 absorption, leading to deficiency.[15] However, the relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency and dementia is not firmly established.[41] Challenges include inaccuracies in measuring B12 and variation across studies in operational definitions of B12 deficiency.[41] The ACT study did not collect measures of B12 deficiency so we cannot answer this question directly. The prevalence of medication-induced B12 deficiency is not known, but it is most likely to occur with long-term gastric acid suppression therapy.[15] Nonetheless, we did not observe a duration-response relationship between PPIs and dementia risk.

A few limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. We examined cumulative dose over a 10-year period, therefore, we were unable to determine whether a dose-response relationship existed (e.g. does omeprazole 40 mg daily confer more risk than 20 mg daily). Most participants in this study were of European ancestry, which may limit generalizability. We had few users in the highest end of our exposure range and cannot entirely rule out a modestly increased risk with high cumulative use, as 95% CIs at the high exposures (e.g., >1460 TSDDs) included HRs as large as 1.4 or 1.5. PPIs became available as OTC in 2003, so there could be misclassification of PPI use. We addressed this by incorporating information about self-reported use collected at study interviews; only 15 participants (< 5%) reported over the counter use.

In summary, our study is the first to combine rigorous ascertainment of dementia status with computerized pharmacy data dating back many years, which allowed us to examine the impact of cumulative PPI use over an extended period of time. Contrary to past studies, we did not find an increased risk of dementia or AD with PPI use. Given the widespread use of PPIs, these results will be of great interest to patients and clinicians weighing risks and benefits of long-term use of these medications. This work is an important step in better understanding the safety of PPI medications. Given some of the conflicting findings across published studies, further research would be helpful in large cohort studies with careful case-finding for dementia and adequate numbers of long-term PPI users. While there are other safety concerns with long-term PPI use, results from our study do not support that patients and clinicians should avoid these medications because of concern over dementia risk.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1: Scheme for Exposure Definition for Proton Pump Inhibitors.

Supplementary Figure S2: Association between Total Duration of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Incident Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease.

Supplementary Figure S3: Association between Longest Duration of Continuous Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Incident Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease.

Supplementary Table S1. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use over the Entire Exposure Period

Supplementary Table S2. Sensitivity Analyses: Association between Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute on Aging U01AG00678 (Dr. Larson).

We would like to thank Drs. Susan McCurry, Wayne McCormick and James Bowen, who participated in multidisciplinary consensus committee meetings that determined study participants’ dementia status.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: This paper was presented in part at the AAIC Annual meeting, Toronto, ON, July 27th, 2016.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors did not play a role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of Interest: EBL receives royalties from UpToDate; RLW received funding as a biostatistician from a research grant awarded to Group Health Research Institute from Pfizer; OY received funding as a biostatistician from research grants awarded to Group Health Research Institute from Bayer; and SLG, SD, EJAB, PKC, MLA have no financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | SLG | RLW | SD | OY | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | MLA | EJAB | PKC | EBL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | x | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | x | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

Authors’ contributions: SLG, MLA, SD, RLW, OY, EJAB, and EBL contributed to study conception and design; all authors contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; SLG and RW drafted the manuscript; all authors revised the manuscript for critical intellectual content; RW conducted statistical analyses; and EBL and PKC obtained funding. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, et al. Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):473–482. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gawron AJ, Pandolfino JE, Miskevics S, et al. Proton pump inhibitor prescriptions and subsequent use in US veterans diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):930–937. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2345-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008 Jan 5;336(7634):2–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39406.449456.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rane PP, Guha S, Chatterjee S, et al. Prevalence and predictors of non-evidence based proton pump inhibitor use among elderly nursing home residents in the US. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.02.012. pii: S1551–7411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Magnitude and economic effect of overuse of antisecretory therapy in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):e228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leri F, Ayzenberg M, Voyce SJ, et al. Four-year trends of inappropriate proton pump inhibitor use after hospital discharge. South Med J. 2013;106(4):270–273. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31828db01f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray SL, LaCroix AZ, Larson J, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use, hip fracture, and change in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(9):765–771. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238–246. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haenisch B, von Holt K, Wiese B, et al. Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(5):419–428. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomm W, von Holt K, Thome F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: A pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410–416. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tai SY, Chien CY, Wu DC, et al. Risk of dementia from proton pump inhibitor use in Asian population: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yepuri G, Sukhovershin R, Nazari-Shafti TZ, et al. Proton pump inhibitors accelerate endothelial senescence. Circ Res. 2016;118(12):e36–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badiola N, Alcalde V, Pujol A, et al. The proton-pump inhibitor lansoprazole enhances amyloid beta production. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sodhi RK, Singh N. Defensive effect of lansoprazole in dementia of AD type in mice exposed to streptozotocin and cholesterol enriched diet. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, et al. PRoton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin b12 deficiency. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2435–2442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, et al. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1737–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002 Apr 13;359(9314):1309–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1994;6(1):45–58. doi: 10.1017/s1041610294001602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):401–407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray SL, LaCroix AZ, Blough D, et al. Is the use of benzodiazepines associated with incident disability? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1012–1018. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamim H, Monfared AA, LeLorier J. Application of lag-time into exposure definitions to control for protopathic bias. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(3):250–258. doi: 10.1002/pds.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray SL, Walker R, Dublin S, Haneuse S, Crane PK, Breitner JC, Bowen J, McCormick W, Larson EB. Histamine-2 receptor antagonist use and incident dementia in an older cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(2):251–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boudreau DM, Yu O, Chubak J, et al. Comparative safety of cardiovascular medication use and breast cancer outcomes among women with early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144:405–16. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2870-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mini-Sentinel Medical Product Assessment. [Accessed April 20, 2017];A Protocol for Assessment of Dabigatran. Available at http://www.mini-sentinel.org/work_products/Assessments/Mini-Sentinel_Protocol-for-Assessment-of-Dabigatran.pdf.

- 27.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [Accessed April 20, 2017];Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/obesity_guidelines_archive.pdf.

- 28.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10(1):20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dublin S, Walker RL, Gray SL, et al. Prescription opioids and risk of dementia or cognitive decline: A prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(8):1519–1526. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emi M, Wu LL, Robertson MA, et al. Genotyping and sequence analysis of apolipoprotein E isoforms. Genomics. 1988;3(4):373–379. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990;31(3):545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hastie T, Tibshirani RJ, Freedman J. Elements of statistical learning. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. Statistical analysis of failure time data. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newcomer R, Clay T, Luxenberg JS, et al. Misclassification and selection bias when identifying Alzheimer’s disease solely from Medicare claims records. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(2):215–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor DH, Jr, Fillenbaum GG, Ezell ME. The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen L, Reed C, Happich M, et al. Health care resource utilisation in primary care prior to and after a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a retrospective, matched case-control study in the United Kingdom. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Health Quality Ontario. Vitamin B12 and cognitive function: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13(23):1–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1: Scheme for Exposure Definition for Proton Pump Inhibitors.

Supplementary Figure S2: Association between Total Duration of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Incident Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease.

Supplementary Figure S3: Association between Longest Duration of Continuous Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Incident Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease.

Supplementary Table S1. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use over the Entire Exposure Period

Supplementary Table S2. Sensitivity Analyses: Association between Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Dementia or Alzheimer’s Disease