Abstract

“Bath salts” preparations contain synthetic cathinones which interact with monoamine transporters and function as either monoamine uptake inhibitors or releasers. 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), 3,4-methylenedioxymethcathinone (methylone), and 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone) were three of the most common cathinones (i.e., “first-generation” cathinones); however, after the US Drug Enforcement Administration placed them under Schedule I regulations, they were replaced with structurally related cathinones that were not subject to regulations (i.e., “second-generation” cathinones). Although the reinforcing effects of some second-generation cathinones have been described (e.g., α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone [α-PVP]), little is known about how structural modifications, particularly those involving the methylenedioxy moiety and α-alkyl side chain, impact the abuse liability of other second-generation cathinones (e.g., α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone [α-PPP], 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinobutiophenone [MDPBP], and 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone [MDPPP]). The present study used male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=12 per drug) to directly compare: (1) the acquisition of responding for α-PVP (0.032 mg/kg/inf), α-PPP (0.32 mg/kg/inf), MDPBP (0.1 mg/kg/inf), and MDPPP (0.32 mg/kg/inf) under a fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcement; and (2) full dose-response curves for each drug to maintain responding under an FR5 schedule of reinforcement. The average number of days (~4 days) and percentage (100%) of rats that acquired self-administration was similar for each drug. The observed rank order potency to maintain responding under an FR5 schedule of reinforcement (α-PVP≈MDPBP>α-PPP>MDPPP) is consistent with their potencies to inhibit dopamine uptake. These are the first studies to report on the reinforcing effects of the unregulated second-generation cathinones MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PPP and indicate all three compounds are readily self-administered, suggesting each possesses high potential for abuse.

1. Introduction1

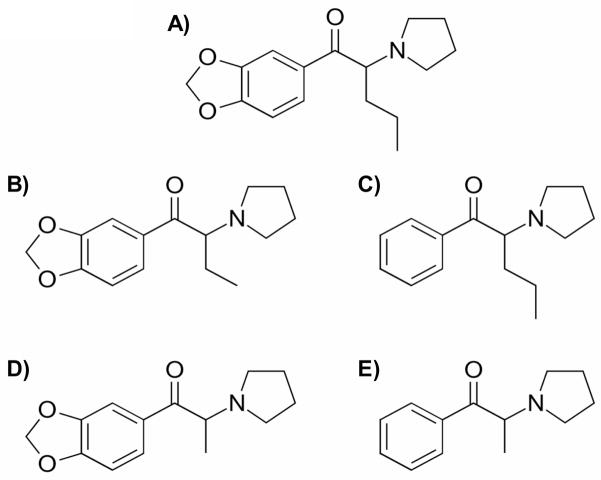

Synthetic cathinones found in “bath salts” preparations account for nearly 25% of all new psychoactive substances (UNODC, 2016). Although originally sold as safe and legal alternatives to illicit stimulants such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), use of these products has been linked to a number of adverse effects including abuse, agitation, paranoia, tachycardia, and death (Johnson and Johnson, 2014; Kyle et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2012; Spiller et al., 2011). Due to the abuse and toxicity associated with use of “bath salts” preparations, three of the most prevalent synthetic cathinones 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), 3,4-methylenedioxymethcathinone (methylone), and 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone) (i.e., the “first-generation” cathinones) were classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as Schedule I compounds (DEA, 2011). Following regulatory control of these first-generation cathinones, a new series of structurally similar (Figure 1) synthetic cathinones (i.e., “second-generation” cathinones) including α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP), α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (α-PPP), 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinobutiophenone (MDPBP), and 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (MDPPP) emerged on the market. Subsequently, the US DEA has placed 10 additional second-generation cathinones, including α-PVP, under Schedule I regulations; however, several hundred synthetic cathinones, including MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PPP, are not currently subject to regulatory control (DEA, 2014).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the first–generation synthetic cathinone (a) MDPV and the second-generation synthetic cathinones (b) MDPBP, (c) α-PVP, (d) MDPPP, and (e) α-PPP.

Synthetic cathinones interact with dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin transporters (DAT, NET, and SERT, respectively) where they function as cocaine-like monoamine uptake inhibitors or amphetamine-like transporter substrates to increase extracellular monoamine levels (Baumann et al., 2013; Eshleman et al., 2013, 2017; Simmler et al., 2013). In rodents, MDPV, α-PVP, α-PPP, and MDPBP have been shown to increase locomotor activity and produce cocaine-, methamphetamine-, and MDMA-like discriminative stimulus effects (e.g., Collins et al., 2016; Fantegrossi et al., 2013; Gannon et al., 2016; Gatch et al., 2013, 2015, 2017; Naylor et al., 2015). MDPV and α-PVP have also been shown to facilitate intracranial self-stimulation and maintain self-administration in rats, suggesting that they function as reinforcers (e.g., Aarde et al., 2015a; 2015b; Gannon et al., 2017a; 2017b; 2017c; Huskinson et al., 2017; Watterson et al., 2014a, 2014b). Additionally, it has been shown that a subset of rats trained to self-administer MDPV (but not cocaine) develop a persistent “high-responder” phenotype, characterized by high levels of drug intake and increased responding during post-infusion timeouts (Gannon et al., 2017b), an effect that may be related to the selective actions of MDPV at DAT relative to SERT (SERT/DAT ~100-800) (Baumann et al., 2013; Eshleman et al., 2013; Simmler et al., 2013). Eshleman and colleagues (2017) recently reported that a number of second-generation cathinones also preferentially inhibit DAT relative to SERT (SERT/DAT ratios: ~3000 for α-PVP, ~350 for α-PPP, ~50 for MDPBP, and ~30 for MDPPP); raising the possibility that rats trained to self-administer these drugs might also develop this high-responder phenotype.

Interestingly, based on functional data reported by Eshleman and colleagues (2017), the presence of a methylenedioxy moiety (e.g., MDPV versus α-PVP) or a longer α-alkyl side chain (e.g., MDPV versus MDPBP) seems related to enhanced potency to inhibit DAT. The same report also suggests that selectivity for DAT over SERT is greater for the synthetic cathinones that lack a methylenedioxy moiety and have a longer α-alkyl side chain (e.g., α-PVP > MDPV > MDPBP). Given that DAT has been shown to be essential for the reinforcing effects of cocaine, the prototypical monoamine reuptake inhibitor (Thomsen et al., 2009), structural differences among these second-generation synthetic cathinones that impact their potency at DAT are also expected to impact their potency to function as reinforcers.

Accordingly, the current studies were designed to test the hypotheses that: (1) rats would acquire responding for regulated (α-PVP) and unregulated (MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PPP) synthetic cathinones; and (2) their potency to maintain responding under a fixed ratio (FR) 5 schedule of reinforcement would be related to their potency to inhibit DAT. Together, these studies provide direct evidence that a number of second-generation cathinones that are structurally related to MDPV function as reinforcers, regardless of regulatory status, and that key attributes of their chemical structures (the presence of a methylenedioxy moiety and the length of the a-alkyl side chain) can be used to predict their abuse-related effects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (275–300 g) obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) were singly housed and maintained on a 10/14-h dark/light cycle with free access to tap water and Purina rat chow in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and the Eighth Edition of the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011).

2.2. Surgery

All rats were implanted with chronic indwelling catheters in the left femoral vein under isoflurane anesthesia as previously described (Gannon et al., 2017a; 2017b; 2017c). Catheters were passed under the skin and attached to a vascular access port positioned between the shoulder blades. Post-surgery, Penicillin G (60,000 U/rat; SC) was administered to prevent infection, and rats were allowed 5–7 days to recover before initiating experiments. Catheters were flushed before (0.2 ml saline) and after (0.5 ml heparinized saline [100 U/ml]) operant sessions daily. If resistance was noted while flushing the catheters either before or after the operant session, catheter patency was further assessed with 3 mg/kg methohexital. All catheters remained patent throughout these studies.

2.3. Apparatus

Experiments were conducted using standard two-lever operant conditioning chambers (Med Associates, St Albans, VT) situated inside sound attenuating cubicles. Above each lever were three LED lights (red, green, and yellow); a white houselight was located at the top center of the opposite wall. Infusions were delivered by a variable speed syringe pump through Tygon® tubing that was connected to a stainless steel fluid swivel and spring tether held in place by a counter-balanced arm.

2.4. Self-Administration

All self-administration sessions were conducted during the light cycle, and all rats were experimentally naïve (no history with operant chambers or drug exposure) prior to initiating self-administration experiments. Illumination of the yellow LED above the active lever (left or right; counterbalanced) served as the discriminative stimulus and signaled drug availability. Completion of the response requirement resulted in a drug infusion (0.1 ml/kg over ~1-sec) and initiated a 5-sec timeout (TO) during which all lights above the active lever and the houselight were illuminated. Responding during timeouts or on the inactive lever were recorded but had no scheduled consequence. Rats (n=12 per drug) were trained to respond under an FR1:TO 5-sec schedule of reinforcement for 0.1 mg/kg/inf MDPBP, 0.32 mg/kg/inf MDPPP, 0.032 mg/kg/inf α-PVP, or 0.32 mg/kg/inf α-PPP across 10 daily 90-min sessions. Doses for acquisition were selected based their relative potencies to inhibit DAT, stimulate locomotor activity, and produce stimulant-like discriminative stimulus effects (Eshleman et al., 2017; Collins et al., 2016; Fantegrossi et al., 2013; Gannon et al., 2016; Gatch et al., 2013, 2015, 2017; Naylor et al., 2015), as well as pilot self-administration studies suggesting that these doses would be on the descending limb of the FR5 dose-response curve. Acquisition of self-administration for each drug was defined as ≥20 infusions for two consecutive days with ≥80% responding on the active lever. After 10 sessions, the response requirement increased to an FR5 for at least an additional 10 sessions and until stability criteria (±20% of the mean number of infusions of 3 consecutive sessions and no increasing or decreasing trend) were met. Dose substitution was then used to generate full dose-response curves for MDPBP (0.001–0.32 mg/kg/inf), MDPPP (0.01–1 mg/kg/inf), α-PVP (0.001-0.1mg/kg/inf), and α-PPP (0.01–1 mg/kg/inf) under the FR5:TO 5-sec schedule of reinforcement. Doses were evaluated in a random order and until stability criteria were met. All rats (n=12 per drug) completed all portions of these experiments.

2.5. Drugs

All drugs were synthesized by Agnieszka Sulima or Kenner Rice at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD), dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline, and administered intravenously in a volume of 0.1 ml/kg.

2.6. Data Analysis

Acquisition data are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) of the number of responses made on the active and inactive levers across the 10-day acquisition phase. The rate of acquisition is reported as the mean ± S.E.M. number of days required for all rats to acquire responding for each drug, and is graphically depicted as the percent of rats in each group that met acquisition criteria as a function of time. Drug-maintained responding during acquisition was analyzed by repeated measures (day) two-way (drug and day) ANOVA followed by a Holm-Sidak’s test for multiple comparisons, whereas rates of acquisition were compared by a survival analysis (timecourse).

Dose-response data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of the number of infusions earned for each unit dose of drug across the 3 days where stability criteria were met. Drug intake was calculated by multiplying the number of infusions earned by the unit dose of the drug and is presented as mean ± S.E.M. total dose of drug earned during the sessions where stability criteria were met. The unit dose that maintained the most responding (i.e., the peak dose) served as a measure of reinforcing potency for individual subjects, and is presented as the group mean ± the 95% confidence intervals. Non-overlapping confidence intervals were used to determine if the reinforcing potencies differed among the second-generation cathinones. One-way ANOVA followed by the Holm-Sidak’s test for multiple comparisons was used to compare the number of infusions earned at the peak dose of each drug. A Pearson’s correlation test was performed to determine if the potency of each drug to maintain peak levels of responding was related to the potency of each drug to inhibit DAT, NET, or SERT, as reported by Eshleman et al. (2017).

The number of days to meet stability criteria are reported as the mean (± S.E.M.) for each dose of each drug, with stability data for each drug analyzed by one-way (dose) repeated measures ANOVA. For individual subjects, the average number of days to stability for each drug (Table 1; All Doses) was determined by averaging the number of days to criteria for each dose. This allowed for within drug comparisons of the number of days to meet stability criteria between high-responders and low-responders by an unpaired t-test with a Welch’s correction. Dose-response curves for the number of infusions earned and total drug intake were compared between high- and low-responders by two-way, repeated measures ANOVAs with post-hoc Holm-Sidak’s tests.

Table 1.

Number of days (± S.E.M.) to meet stability criteria for each doses of each drug tested.

| MDPBP | MDPPP | α-PVP | α-PPP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Grouped (n=12) | Saline | 3.3 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.2) |

| 0.001 | 4.5 (0.6) | --- | 5.1 (0.7) | --- | |

| 0.0032 | 4.0 (0.2) | --- | 4.4 (0.4) | --- | |

| 0.01 | 4.1 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.4) | |

| 0.032 | 3.7 (0.2) | 6.5 (0. 8) | 4.2 (0.6) | 4.8 (0. 7) | |

| 0.1 | 3.6 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.4) | 3.6 (0.2) | |

| 0.32 | 3.3 (0.2) | 3.5 (0.3) | --- | 3.7 (0.4) | |

| 1 | --- | 3.3 (0.3) | --- | 3.3 (0.1) | |

|

| |||||

| All Doses | 3.8 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.3) | 4.2 (0.2) | |

|

| |||||

| Low-Responders | Saline | 3.2 (0.1) | 3.6 (0.2) | 4.3 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.3) |

| 0.001 | 4.6 (0.7) | --- | 4.1 (0.7) | --- | |

| 0.0032 | 4.0 (0.3) | --- | 4.6 (0.7) | --- | |

| 0.01 | 4.1 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.3) | 3.1 (0.1) | 5.5 (0.6) | |

| 0.032 | 3.6 (0.2) | 6.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.6) | |

| 0.1 | 3.2 (0.2) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.2) | |

| 0.32 | 3.0 (0.0) | 3.2 (0.1) | --- | 3.3 (0.2) | |

| 1 | --- | 3.1 (0.1) | --- | 3.3 (0.2) | |

|

| |||||

| All Doses | 3.8 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.2) | 3.9 (0.1) | |

|

| |||||

| High-Responders | Saline | 3.5 (0.5) | 5.0 (---) | 4.8 (1.0) | 3.5 (0.3) |

| 0.001 | 4.0 (0.0) | --- | 6.4 (1.2) | --- | |

| 0.0032 | 4.0 (0.0) | --- | 4.2 (0.5) | --- | |

| 0.01 | 4.0 (0.0) | 8.0 () | 6.0 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.5) | |

| 0.032 | 4.0 (1.0) | 9.0 (---) | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.3 (1.0) | |

| 0.1 | 5.5 (0.5) | 4.0 (---) | 4.6 (0.7) | 3.8 (0.2) | |

| 0.32 | 4.5 (1.5) | 7.0 (---) | --- | 3.9 (0.6) | |

| 1 | --- | 6.0 (---) | --- | 3.4 (0.2) | |

|

| |||||

| All Doses | 4.3 (0.5) | 6.8 (---) | 5.3 (0.5)# | 4.3 (0.3) | |

indicates statistically different (p < 0.05) compared with low responders. Group sizes for high-responders and low-responders are n=2 and n=10 for MDPBP, n=1 and n=11 for MDPPP, n=5 and n=7 for α-PVP, n=8 and n=4 for α-PPP, respectively.

Active lever responses made during the post-infusion timeouts are expressed as the percentage of active lever responses during the timeout relative to the total number of active lever responses and plotted as a frequency distribution using 10% bins. Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used to generate figures and conduct statistical analyses.

3. Results

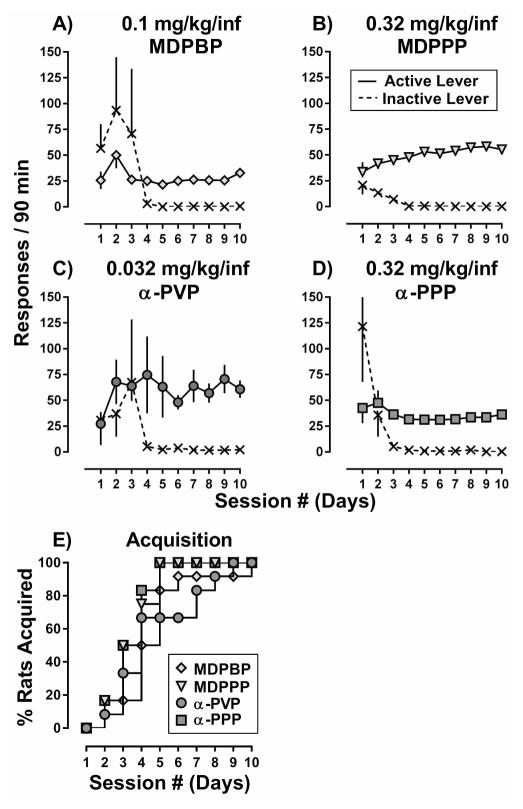

As shown in Figure 2, rats readily acquired responding for 0.1 mg/kg/inf MDPBP (A), 0.32 mg/kg/inf MDPPP (B), 0.032 mg/kg/inf α-PVP (C), or 0.32 mg/kg/inf α-PPP (D), with 100% of rats acquiring responding by the end of the 10-day period (E). The mean time to acquire was not significantly different among the groups, with acquisition of responding occurring in 4.8 ± 0.6 days for MDPBP, 3.6 ± 0.3 days for MDPPP, 4.8 ± 0.7 days for α-PVP, and 3.5 ± 0.3 days for α-PPP. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures revealed a main effect of drug (F[3,434]=17.4, p<0.001) but not day (F[9,434]=0.6, p=0.77) on the mean number of active lever responses (infusions earned) during the acquisition period with α-PVP maintaining more responses (infusions) than MDPBP (days 4, 5, 6, and 8) and α-PPP (days 4, 5, and 6) (p<0.05). However, by the end of the acquisition phase, no significant differences were detected among the drugs. A substantial amount of responding on the inactive lever was noted during the first few days of acquisition for all drugs; however, this effect was absent by the end of the acquisition period.

Figure 2.

Acquisition of responding for (A) 0.1 mg/kg/inf MDPBP, (B) 0.32 mg/kg/inf MDPPP, (C) 0.032 mg/kg/inf α-PVP, and (D) 0.32 mg/kg/inf α-PPP over the course of the 10-day acquisition phase in male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=12 per drug). Filled symbols represent active lever responses and unfilled symbols represent inactive lever responses. Abscissa: Numbers refer to sessions conducted on consecutive days during the acquisition period. Ordinate: Total responses emitted on each lever during the active portion of the 90-minute session. Error bars represent ± S.E.M. (E) Percent of MDPBP (diamonds), MDPPP (triangles), α-PVP (circles), and α-PPP (squares) rats that acquires self-administration over the course of 10 days. Abscissa: numbers refer to consecutive days during the acquisition period. Ordinate: cumulative percent of rats within each training group to acquire self-administration of the training drug/dose.

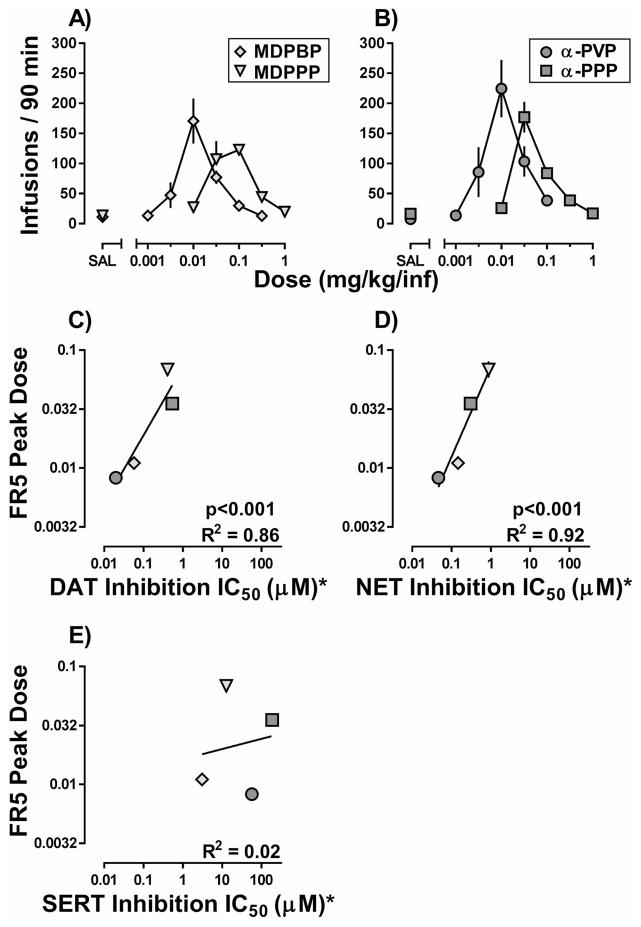

Figure 3 (top row) shows the number of infusions earned for each unit dose of MDPBP and MDPPP (A; diamonds and triangles, respectively) or α-PVP and α-PPP (B; circles and squares, respectively) under an FR5 schedule of reinforcement. A one-way, repeated measures ANOVA indicated the number of days to meet stability criteria did not differ as a function of dose for MDPBP (F[5,55]=1.4, p=0.24) or α-PVP (F[4,44]=1.1, p=0.35); however, the number of day to stability varied as a function of dose for MDPPP (F[4,44]=11.2, p<0.001) and α-PPP (F[4,44]=5.2, p<0.01) (Table 1). Although slight differences in the number of infusions earned at the peak dose were observed among α-PVP (223.4 ± 48.0 infusions), α-PPP (176.9 ± 25.7 infusions), MDPBP (170.7 ± 37.6 infusions), and MDPPP (122.9 ± 9.1 infusions) these differences were not significant. Importantly, significant differences in reinforcing potency (i.e., peak of the dose response-curve) were observed among the cathinones, with a rank order potency of α-PVP (0.008 [0.006, 0.011] mg/kg/inf) ≈ MDPBP (0.011 [0.009, 0.013] mg/kg/inf) > α-PPP (0.035 [0.029, 0.042] mg/kg/inf) > MDPPP (0.068 [0.050, 0.094] mg/kg/inf). In order to determine whether the reinforcing effects of the cathinones were related to their capacity to inhibit dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin uptake, the potencies to maintain responding were compared to previously reported IC50 values for each drug to inhibit monoamine uptake at DAT, NET and SERT (Eshleman et al., 2017). As shown in Figure 3, the reinforcing potencies of the second-generation cathinones were positively correlated with their potency to inhibit DAT (Figure 3C) and NET (Figure 3D) but not SERT (Figure 3E), with R-squared values of these linear regressions equal to 0.86, 0.92, and 0.02, respectively.

Figure 3.

Dose-response curves for the self-administration of (A) MDPBP and MDPPP and (B) α-PVP and α-PPP obtained under an FR5:TO 5-sec schedule of reinforcement. Abscissa: “SAL” represents infusions of saline, whereas numbers refer to the unit dose of MDPBP (diamonds), MDPPP (triangles), α-PVP (circles), or α-PPP (squares) available during each session. Ordinate: Mean number of infusions obtained during the 90-minute session. Error bars represent ± S.E.M. Correlations between the mean dose of MDPBP (diamonds), MDPPP (triangles), α-PVP (circles), or α-PPP (squares) that maintained the largest number of infusions under an FR5:TO 5-sec schedule of reinforcement and the potency (IC50) of each drug to inhibit uptake at (C) DAT, (D) NET, or (E) SERT. Abscissa: Numbers refer to the concentration of MDPBP (diamonds), MDPPP (triangles), α-PVP (circles), or α-PPP (squares) necessary to inhibit monoamine reuptake by 50%, expressed as μM on a log scale. Ordinate: Group means of the dose of each drug that maintained the most responding. Error bars represent ± S.E.M. Asterisk indicates the IC50 values for each drug at DAT, NET, and SERT were reported by Eshleman et al., 2017.

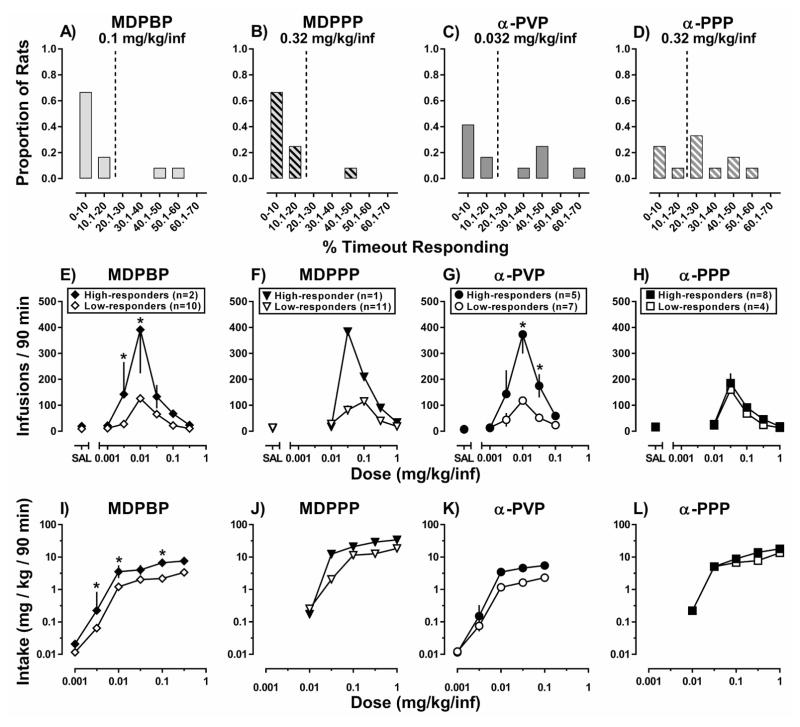

The criteria previously established to characterize individual differences in MDPV self-administration (percent active lever responses emitted during timeout periods; Gannon et al., 2017b) were used to probe for individual differences in responding for MDPBP, MDPPP, α-PVP, and α-PPP (Figure 4 top row). The number of rats exhibiting >20% of their responses during timeouts (high-responders) differed among the drugs (α-PPP [n=8] > α-PVP [n=5] > MDPBP [n=2] > MDPPP [n=1]); statistical analyses of differences between high- and low-responders were not conducted for MDPPP (Figure 4F; 4J) because only one rat exhibited the high-responder phenotype. The number of days to meet stability criteria differed between high-responders and low-responders for α-PVP (Table 1; t=3.01, p<0.05), but not MDPBP (t=1.00, p=0.46) or α-PPP (Table 1; t=3.58, p=0.16). With regard to the number of infusions earned, although each drug maintained responding in a dose-dependent manner (MDPBP: F[6,60]=40.4; p<0.001; MDPPP: F[5,50]=48.9; p<0.001; α-PVP: F[5,50]=20.5; p<0.001; α-PPP: F[5,50]=27.4; p<0.001), a main effect of responding phenotype (i.e., dose-response curves for high-responders were shifted upward relative to the low-responders) was observed for MDPBP (F[1,10]=15.8; p<0.01) (Figure 4E), and α-PVP (F[1,10]=10.4; p<0.01) (Figure 4G), but not for α-PPP (F[1,10]=1.1; p=0.32) (Figure 4H). Although total session intake increased as a function of the unit dose available for injection for MDPBP (F[5,50]=215.6; p<0.001) (Figure 4I), MDPPP (F[4,40]=98.2; p<0.001) (Figure 4J), α-PVP (F[4,40]=165.4; p<0.001) (Figure 4K), and α-PPP (F[4,40]=218.6; p<0.001) (Figure 4L), a main effect of responder phenotype was only observed for MDPBP (F[1,10]=18.2; p<0.01), and α-PVP (F[1,10]=7.9; p<0.05), with no significant effect of responding phenotype on α-PPP intake (F[1,10]=2.0; p=0.19).

Figure 4.

Distribution of (A) MDPBP-trained, (B) MDPPP-trained, (C) α-PVP-trained, and (D) α-PPP-trained rats based on timeout responding. Abscissa: percent of total responses emitted on the active lever occurring during the post-infusion timeout, presented in 10% bins. Ordinate: proportion of rats in each group (n=12 per drug). Self-administration dose-response curves for low-responders (white symbols) and high-responders (black symbols) obtained under an FR5:TO 5-sec schedule of reinforcement. Abscissa: “SAL” represents infusions of saline, while numbers refer to the unit dose of (E) MDPBP, (F) MDPPP, (G) α-PVP, or (H) α-PPP available during each session expressed as mg/kg/inf on a log scale. Ordinate: Mean number of infusions obtained during the 90-minute session. Drug intake for low-responders (white symbols), high-responders (black symbols), and the group (gray symbols) during the 90-min self-administration session. Abscissa: Numbers refer to the unit dose of (I) MDPBP, (J) MDPPP, (K) α-PVP, or (L) α-PPP available during each session expressed as mg/kg/inf on a log scale. Ordinate: Mean drug intake obtained during the 90-minute session. Error bars represent ± S.E.M. *, p<0.05; represent differences in the number of infusion earned, or total drug intake between high- and low-responders as determined by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc Holm-Sidak’s tests [n.b., statistics were not performed for MDPPP because only 1 rat exhibited the high-responder phenotype].

4. Discussion

The use and abuse of designer drugs, such as synthetic cathinones, has increased dramatically over the past decade, and seizures of synthetic cathinones found in “bath salts” preparations have progressively increased on an international level since 2010 (UNODC, 2016). Also trending is the introduction of new synthetic cathinones to the marketplace, many of which are structurally related to previously reported/regulated cathinones, such as MDPV and α-PVP (UNODC, 2016). As a result of the ever-evolving nature of cathinone-containing “bath salts” preparations, relatively little is known about how these structural modifications can impact their abuse-related effects. Accordingly, the present study directly compared the reinforcing effects of several structurally similar synthetic cathinones, including currently regulated (α-PVP) and unregulated (MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PPP) cathinones, to determine how structural modifications impact their abuse liability. Self-administration of MDPBP, MDPPP, α-PVP, and α-PPP was rapidly acquired, and each drug maintained responding over a range of doses, suggesting that each of these second-generation cathinones functions as a reinforcer. Similar to previous reports with MDPV (Gannon et al., 2017b), self-administration of these second-generation cathinones was also associated with high levels of inactive lever responding during the first ~4 days of access; however, this effect was short-lived. Together, the present study suggests that the length of the α-alkyl side chain is positively correlated with the reinforcing potency of these synthetic cathinones, and provides strong evidence that these second-generation cathinones function as reinforcers in rats and have the potential to be abused by humans.

The potency of a drug to maintain responding is often related to its potency to produce other behavioral effects (e.g., Spealman and Kelleher, 1981). In the current study, the rank order of the potency of these second-generation cathinones to maintain responding was α-PVP ≈ MDPBP > α-PPP > MDPPP. Although this rank order is similar to that reported for drug discrimination, it differs from that reported for locomotor stimulation (MDPBP > α-PVP ≈ α-PPP) (Gatch et al., 2015; 2017), suggesting the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of these drugs are mediated by similar mechanisms, but may only partially overlap with those that underlie their effects on locomotor activity. Notably, when the potency of each drug to function as a reinforcer was compared to its potency to inhibit uptake at DAT, NET, and SERT (Eshleman et al., 2017), a positive correlation was observed for DAT and NET, but not SERT. Consistent with previous reports linking the reinforcing effects of drugs acting at monoamine transporters to their actions at DAT (e.g., Lile et al., 2003; Thomsen et al., 2009; Wilcox et al., 2000, 2005), the current studies suggest that the potency of these second-generation cathinones to reinforce responding is related to their capacity to inhibit dopamine uptake.

The present findings also suggest that key attributes of the chemical structures of these synthetic cathinones are related to their reinforcing effects, with longer α-alkyl side chains resulting in more potent reinforcers than otherwise identical cathinones (e.g., MDPBP is more potent than MDPPP, and α-PVP is more potent than α-PPP). This notion is further supported by comparing the potencies of MDPBP and MDPPP to that which we previously reported for MDPV (Gannon et al., 2017b). Indeed, reducing the length of the α-alkyl side chain from three carbons (MDPV) to two carbons (MDPBP) to one carbon (MDPPP) results in a similar reduction in the potency of these drugs to reinforce responding. In addition, because MDPV (Gannon et al., 2017b) is more potent than α-PVP at maintaining responding under fixed ratio schedules of reinforcement, it is also possible that the presence of the methylenedioxy moiety influences the reinforcing potency of these structurally related cathinones. However, because the current studies did not include direct comparisons between MDPBP and α-PBP, and because MDPPP was found to be less potent than α-PPP, further studies are required to determine how the methylenedioxy moiety impacts the reinforcing effects of these synthetic cathinones.

In addition to maintaining high levels of responding, MDPBP, MDPPP, α-PVP, and α-PPP also occasioned high levels of active lever responding during timeout periods, an effect we and others have previously shown to be associated with higher levels of MDPV intake (Aarde et al., 2015b; Gannon et al., 2017b), and has been suggested to represent a compulsive pattern of responding that may contribute to addiction in humans (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2004). These observations appear to be consistent with the human “bath salts” literature, where intense craving and compulsive patterns of drug-taking are noted (e.g., Johnson and Johnson, 2014; Winstock et al., 2011). Although small group sizes limited the power for statistical comparisons between high- and low-responders, responding tended to be more variable on a day-to-day basis for high-responders relative to low-responders, resulting in a trend for high-responders to meet stability criteria slower than low-responders for each drug. Similar to what we have previously reported for MDPV (Gannon et al., 2017b), these high levels of timeout responding were associated with marked increases in drug intake when MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PVP were available. Curiously, although 8 of 12 rats responding for α-PPP met criteria to be considered a high-responder (i.e., >20% of active lever responses occurring during the timeout), these rats only earned slightly more infusions and had only slightly greater levels of intake relative to their low-responder counterparts. Interestingly, MDPV, MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PVP are all more potent at inhibiting uptake at DAT than NET or SERT, whereas α-PPP is more potent at inhibiting uptake at NET than DAT or SERT (Baumann et al., 2013; Eshleman et al., 2013; 2017 Simmler et al., 2013). Thus, whereas large SERT/DAT ratios (e.g., MDPV, MDPBP, MDPPP, α-PVP, and α-PPP) may be sufficient for a drug to establish high levels of timeout responding, selectivity for DAT over NET may be necessary for a this behavioral phenotype to drive higher levels of drug intake. Although we have not yet determined the mechanism(s) responsible for the development of this high-responder phenotype, the fact that it has been observed in rats trained to MDPV, MDPBP, MDPPP, α-PVP, and α-PPP, but not cocaine (Gannon et al., 2017b) suggests that it may be related to the pharmacology of synthetic cathinones with an MDPV-like structure.

5. Conclusions

The ever-changing face of designer drugs (e.g., synthetic cathinones and synthetic cannabinoids) has created an evolving threat to public health and introduced new challenges to physicians, law enforcement, and regulators. As regulations evolve to control the emergence of designer drugs of abuse, a better understanding of the relationship between chemical structure, pharmacology, and abuse potential is essential. The present study characterized the reinforcing effects of four second-generation cathinones, and found that responding for each of these cathinones was rapidly acquired and not different from previous reports for the first-generation cathinone, MDPV (Gannon et al. 2017b). Although self-administration of α-PVP (DEA Schedule I) has previously been described (Aarde et al., 2015a; Gannon et al., 2017c; Huskinson et al., 2017), these studies provide new and important information about the reinforcing effects of MDPBP, MDPPP, and α-PPP, and suggest that they each possess a high potential for abuse. In addition, all four of these synthetic cathinones established high levels of drug intake and/or compulsive-like patterns of responding during post-infusion timeouts in a subset of rats. The potency of these second-generation cathinones to maintain responding was positively correlated with their potency to inhibit DAT and NET, a relationship that appears to be determined by the length of the α-alkyl side chain. Collectively, these data suggest the abuse-related effects of the selected, unregulated second-generation cathinones may be similar to those of Schedule I synthetic cathinones, such as MDPV and α-PVP; however, more work is needed to determine whether the structure activity relationships reported herein for reinforcing potency also extend to measures of reinforcing effectiveness.

Highlights.

Self-administration of the structurally related synthetic cathinones 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinobutiophenone (MDPBP), 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone

(MDPPP), α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP), and α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (α-PPP) was rapidly acquired.

Responding for MDPBP, MDPPP, α-PVP, and α-PPP was maintained over a range of doses.

The potency of each drug to reinforce responding was related to its potency to inhibit dopamine uptake.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA039146) (GTC); a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32DA031115) (BMG); and the NIH Intramural Research Programs of NIDA and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (KCR). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), 3,4-methylenedioxymethcathinone (methylone), 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP), α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (α-PPP), 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinobutiophenone (MDPBP), 3,4-methylenedioxy-α-pyrrolidinopropiophenone (MDPPP), dopamine transporter (DAT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), serotonin transporter (SERT), fixed ratio (FR), timeout (TO), standard error of the mean (S.E.M), analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarde SM, Creehan KM, Vandewater SA, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. In vivo potency and efficacy of the novel cathinone α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone: self-administration and locomotor stimulation in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015a;232:3045–3055. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarde SM, Huang PK, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. Binge-like acquisition of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) self-administration and wheel activity in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015b;232:1867–1877. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3819-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR, Thorndike EB, Hoffman AF, Holy M, et al. Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive 'bath salts' products. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:552–562. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Abbott M, Galindo K, Rush EL, Rice KC, France CP. Discriminative Stimulus Effects of Binary Drug Mixtures: Studies with Cocaine, MDPV, and Caffeine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;359:1–10. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.234252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D, Piazza PV. Evidence for addiction-like behavior in the rat. Science. 2004;305:1014–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1099020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice. Schedules of controlled substances: temporary placement of three synthetic cathinones into Schedule I. Final Order. Fed Regist. 2011;76:65371–65375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice. Schedules of controlled substances: temporary placement of 10 synthetic cathinones into Schedule I. Final Order. Fed Regist. 2014;79:12938–12943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman AJ, Wolfrum KM, Hatfield MG, Johnson RA, Murphy KV, Janowsky A. Substituted methcathinones differ in transporter and receptor interactions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1803–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman AJ, Wolfrum KM, Reed JF, Kim SO, Swanson T, Johnson RA, et al. Structure-Activity Relationships of Substituted Cathinones, with Transporter Binding, Uptake, and Release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;360:33–47. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.236349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantegrossi WE, Gannon BM, Zimmerman SM, Rice KC. In vivo effects of abused 'bath salt' constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) in mice: drug discrimination, thermoregulation, and locomotor activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:563–573. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Galindo KI, Mesmin MP, Rice KC, Collins GT. Reinforcing effects of binary mixtures of common bath salts constituents: studies with 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), 3,4-methylenedioxymethcathinone (methylone), and caffeine in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017a doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.141. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Galindo KI, Rice KC, Collins GT. Individual Differences in the Relative Reinforcing Effects of 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone under Fixed and Progressive Ratio Schedules of Reinforcement in Rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017b;361:181–189. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.239376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Rice KC, Collins GT. Reinforcing effects of abused “bath salts” constituents 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) and α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP) and their enantiomers. Behav Pharmacol. 2017c doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000315. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon BM, Williamson A, Suzuki M, Rice KC, Fantegrossi WE. Stereoselective effects of abused "bath salt" constituent 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone in mice: drug discrimination, locomotor activity, and thermoregulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;356:615–623. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Dolan SB, Forster MJ. Comparative behavioral pharmacology of three pyrrolidine-containing synthetic cathinone derivatives. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:103–110. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.223586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Dolan SB, Forster MJ. Locomotor activity and discriminative stimulus effects of a novel series of synthetic cathinone analogs in mice and rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017;234:1237–1245. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4562-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Taylor CM, Forster MJ. Locomotor stimulant and discriminative stimulus effects of 'bath salt' cathinones. Behav Pharmacol. 2013;24:437–447. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328364166d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskinson SL, Naylor JE, Townsend EA, Rowlett JK, Blough BE, Freeman KB. Self-administration and behavioral economics of second-generation synthetic cathinones in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2017;234:589–598. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PS, Johnson MW. Investigation of "bath salts" use patterns within an online sample of users in the United States. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46:369–378. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.962717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle PB, Iverson RB, Gajagowni RG, Spencer L. Illicit bath salts: not for bathing. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2011;52:375–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Wang Z, Woolverton WL, France JE, Gregg TC, Davies HM, et al. The reinforcing efficacy of psychostimulants in rhesus monkeys: the role of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:356–366. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray BL, Murphy CM, Beuhler MC. Death following recreational use of designer drug "bath salts" containing 3,4-Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) J Med Toxicol. 2012;8:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0196-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8. National Academy Press; Washington DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor JE, Freeman KB, Blough BE, Woolverton WL, Huskinson SL. Discriminative-stimulus effects of second generation synthetic cathinones in methamphetamine-trained rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmler LD, Buser TA, Donzelli M, Schramm Y, Dieu LH, Huwyler J, et al. Pharmacological characterization of designer cathinones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:458–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Kelleher RT. Self-administration of cocaine derivatives by squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;216:532–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller HA, Ryan ML, Weston RG, Jansen J. Clinical experience with and analytical confirmation of “bath salts” and “legal highs” (synthetic cathinones) in the United States. Clin Toxicol. 2011;49:499–505. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.590812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Caine SB. Dramatically decreased cocaine self-administration in dopamine but not serotonin transporter knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1087–1092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4037-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2016. United Nations publication; 2016. Sales No. E.16.XI.7. [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Burrows BT, Hernandez RD, Moore KN, Grabenauer M, Marusich JA, et al. Effects of α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 4-methyl-N-ethylcathinone, two synthetic cathinones commonly found in second-generation "bath salts," on intracranial self-stimulation thresholds in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014a;18 doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu014. pii: pyu014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson LR, Kufahl PR, Nemirovsky NE, Sewalia K, Grabenauer M, Thomas BF, et al. Potent rewarding and reinforcing effects of the synthetic cathinone 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Addict Biol. 2014b;19:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox KM, Kimmel HL, Lindsey KP, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Howell LL. In vivo comparison of the reinforcing and dopamine transporter effects of local anesthetics in rhesus monkeys. Synapse. 2005;58:220–228. doi: 10.1002/syn.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox KM, Rowlett JK, Paul IA, Ordway GA, Woolverton WL. On the relationship between the dopamine transporter and the reinforcing effects of local anesthetics in rhesus monkeys: practical and theoretical concerns. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;153:129–147. doi: 10.1007/s002130000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock A, Mitcheson L, Ramsey J, Davies S, Puchnarewicz M, Marsden J. Mephedrone: use, subjective effects and health risks. Addiction. 2011;106:1991–1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]