Summary

T‐DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to its host plant genome relies on multiple interactions between plant proteins and bacterial effectors. One such plant protein is the Arabidopsis VirE2 interacting protein (AtVIP1), a transcription factor that binds Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 VirE2, potentially acting as an adaptor between VirE2 and several other host factors. It remains unknown, however, whether the same VirE2 protein has evolved to interact with multiple VIP1 homologues in the same host, and whether VirE2 homologues encoded by different bacterial strains/species recognize AtVIP1 or its homologues. Here, we addressed these questions by systematic analysis (using the yeast two‐hybrid and co‐immunoprecipitation approaches) of interactions between VirE2 proteins encoded by four major representatives of known bacterial species/strains with functional T‐DNA transfer machineries and eight VIP1 homologues from Arabidopsis and tobacco. We also analysed the determinants of the VirE2 sequence involved in these interactions. These experiments showed that the VirE2 interaction is degenerate: the same VirE2 protein has evolved to interact with multiple VIP1 homologues in the same host, and different and mutually independent VirE2 domains are involved in interactions with different VIP1 homologues. Furthermore, the VIP1 functionality related to the interaction with VirE2 is independent of its function as a transcriptional regulator. These observations suggest that the ability of VirE2 to interact with VIP1 homologues is deeply ingrained into the process of Agrobacterium infection. Indeed, mutations that abolished VirE2 interaction with AtVIP1 produced no statistically significant effects on interactions with VIP1 homologues or on the efficiency of genetic transformation.

Keywords: Agrobacterium, VirE2, VIP1, protein‐protein interactions

Introduction

During plant genetic transformation mediated by Agrobacterium spp., the transferred DNA (T‐DNA) in a single‐stranded (ss) form and several bacterial protein effectors are exported into the host cell cytoplasm. Multiple interactions between different bacterial and host proteins facilitate and control the transport of T‐DNA into the cell nucleus and its integration into the host genome (Gelvin, 2003; Lacroix and Citovsky, 2013b). Some host factors interacting with Agrobacterium effectors represent housekeeping cellular pathways and are diverted from their native functions to facilitate T‐DNA transfer, whereas others represent host responses aimed at controlling or preventing Agrobacterium infection. Within the host cell, two of the bacterial effectors are thought to associate with the transported T‐DNA molecule: VirD2 and VirE2. VirD2 is covalently attached to the 5′ end of the T‐DNA strand (Ward and Barnes, 1988; Young and Nester, 1988). VirE2 is an ssDNA‐binding protein (Christie et al., 1988; Citovsky et al., 1989; Sen et al., 1989) that packages ssDNA into a helical nucleoprotein complex (Abu‐Arish et al., 2004; Citovsky et al., 1997), suggesting that VirE2 plays a role in protecting T‐DNA from degradation and mediating its interactions with host factors.

One of the plant proteins that interacts with VirE2 is VIP1 (VirE2‐interacting protein 1), a transcription factor of the bZIP family (Tzfira et al., 2001) involved in the stress response (Djamei et al., 2007; Pitzschke et al., 2009) and the osmosensory and touch responses (Tsugama et al., 2014, 2016). VIP1 has been suggested to act as a molecular adaptor between VirE2 and several host cell factors, such as importin α of the nuclear import pathway (Citovsky et al., 2004; Tzfira et al., 2001, 2002), plant and bacterial F‐box proteins, such as VirF and VBF, of the proteasomal degradation pathway (Tzfira et al., 2004; Zaltsman et al., 2010, 2013), and nucleosomal histones (Lacroix et al., 2008; Loyter et al., 2005). However, a recent study has challenged the role(s) of VIP1 in the Agrobacterium–plant cell interaction: using a root assay in Arabidopsis thaliana, it was reported that Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation efficiency was not affected in an Arabidopsis line with an insertional mutation in the VIP1 gene (Shi et al., 2014). Potentially, this could be a result of the overlapping activities of numerous VIP1 homologues encoded by the Arabidopsis genome that are redundant in their subcellular localization and transcriptional activation function (Tsugama et al., 2014). Furthermore, although VirE2 is important for T‐DNA transfer, it is not absolutely necessary, and a virE2 mutant of Agrobacterium tumefaciens retains a low level of virulence (Horsch et al., 1986; Stachel et al., 1985). This is consistent with the diversity of the potential pathways involved in Agrobacterium‐mediated genetic transformation of plants. Here, we explore this diversity by investigating the interactions between VirE2 from different bacterial strains and several members of the VIP1 family in Arabidopsis and tobacco, and the determinants of the VirE2 sequence involved in these interactions.

Results

Homologues of AtVIP1 in A. thaliana and other plant species

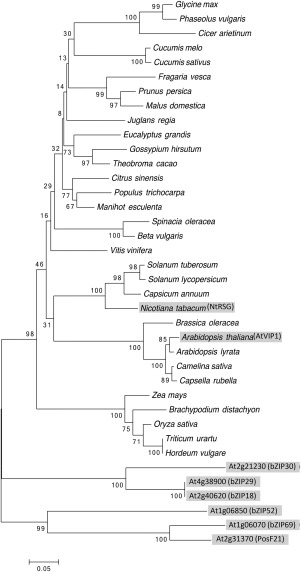

VIP1 belongs to the large family of bZIP (basic region/leucine zipper) domain transcription factors, present in all eukaryotes whose genomes have been sequenced so far; the bZIP protein family of Arabidopsis comprises 75 members—four times more than yeast, worm or human—involved in such diverse processes as plant development, light signalling, and biotic and abiotic stress responses (Jakoby et al., 2002). Based on basic region sequence similarity and on the presence of conserved motifs, Arabidopsis bZIP proteins have been clustered into 10 groups (Jakoby et al., 2002). AtVIP1 belongs to group I; within this group, phylogenetic analysis defined several subgroups, with AtVIP1 and six other bZIP proteins belonging to subgroup 1 (Tsugama et al., 2014). Homologues of AtVIP1 are encoded by genomes of many other plant species. Figure 1, which shows a phylogenetic tree of 38 of the closest homologues of AtVIP1 in different species from the main taxa of higher plants (summarized in Table S1, see Supporting Information), suggests that most plant species in the angiosperm group encode proteins closely related to AtVIP1, forming a clade distinct from the rest of the Arabidopsis bZIP proteins of the subgroup I‐1. Generally, the phylogeny of the VIP1 homologues reflects the phylogeny of the species: for example, VIP1‐like proteins from monocotyledonous plants are grouped into a single clade, distinct from the VIP1‐like sequences from dicotyledonous plants. Thus, bZIP proteins from other angiosperm species that are closely related to AtVIP1 probably represent AtVIP1 orthologues. We selected all proteins from the Arabidopsis subgroup I‐1, i.e. VIP1, bZIP18, bZIP52, bZIP69, posF21, bZIP29 and bZIP30, as well as the Nicotiana tabacum VIP1 orthologue NtRSG (Fig. 1) as an example of a non‐Arabidopsis VIP1‐like protein, to examine their potential interactions with VirE2.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of AtVIP1, its orthologues from representative plant species and Arabidopsis homologues from the same subgroup. AtVIP1, its six closest Arabidopsis thaliana homologues and the Nicotiana tabacum orthologue are highlighted by shaded boxes. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbour‐joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The optimal tree with the sum of branch lengths = 3.60596289 is shown. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches (Felsenstein, 1985). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method (Zuckerkandl and Pauling, 1965) and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The analysis involved 38 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 179 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis tool (MEGA, version 6.0.5 for Mac OS) (http://www.megasoftware.net) (Tamura et al., 2013), which also generated this description of the analysis. Scale bar, 0.05 amino acid substitutions per site.

Interactions between VirE2 from different bacterial strains and AtVIP1 and its homologues

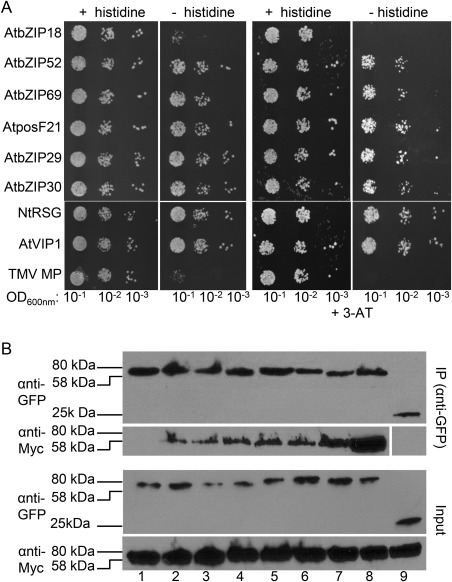

Initially, we examined potential interactions between VirE2 from Agrobacterium C58 and VIP1 homologues in a yeast two‐hybrid system, in which cell growth on a histidine‐deficient medium indicates interaction. Figure 2A shows that VirE2 interacted with five of six Arabidopsis VIP1 homologues tested, i.e. bZIP52, bZIP69, posF21, bZIP29 and bZIP30, as well as with VIP1 and NtRSG, but not with bZIP18. This interaction ability of VirE2 was specific because it was not observed with an unrelated control protein, the cell‐to‐cell movement protein (MP) of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) (Citovsky et al., 1990; Wolf et al., 1989) (Fig. 2A). To demonstrate further the selectivity of these interactions, we utilized 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT), a competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 gene product, which selects for stronger interactions that produce sufficient histidine to sustain the inhibition and allow cell survival. Indeed, under these conditions, we still observed the identified interactions of VirE2 with VIP1 homologues (Fig. 2A). Conversely, the negative control TMV MP promoted only weak cell growth, which was completely suppressed by 3‐AT (Fig. S1, see Supporting Information), indicating a lack of TMV MP interaction with any of the tested VIP1 homologues. Under non‐selective conditions, i.e. in the presence of histidine, all combinations of the tested proteins resulted in efficient cell growth, indicating that none of the constructs interfered with cell viability (Figs 2A and S1). Notably, histidine prototrophy alone may also detect weak two‐hybrid interactions, which may or may not affect the functional relevance of these interactions.

Figure 2.

Interaction of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 VirE2 with AtVIP1 and its homologues. (A) Yeast two‐hybrid interaction assay. LexA‐C58 VirE2 was co‐expressed with Gal4‐AD fused to the indicated tested proteins. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT). (B) Co‐immunoprecipitation interaction assay. C58 VirE2‐Myc was expressed with GFP‐AtVIP1 and its GFP‐tagged homologues for 3 days in agroinfiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti‐GFP antibody (top panel), followed by western blot analysis with anti‐GFP or anti‐Myc antibody. To visualize the total amounts of the tested proteins (Input), they were analysed by western blotting with anti‐GFP or anti‐Myc antibody without immunoprecipitation. Lane 1, AtbZIP18; lane 2, AtbZIP52; lane 3, AtbZIP69; lane 4, AtposF21; lane 5, AtbZIP29; lane 6, AtbZIP30; lane 7, NtRSG; lane 8, AtVIP1; lane 9, free green fluorescent protein (GFP). Two independent experiments were performed for each assay with similar results.

The yeast two‐hybrid results were then validated by an independent approach, in which individual VIP1 homologues tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) were co‐expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves with C58 VirE2 tagged with the Myc epitope and immunoprecipitated with anti‐GFP antibody followed by western blot analysis. Figure 2B shows that the resulting immunoprecipitates contained both VIP1 homologues detected by anti‐GFP and VirE2 detected by anti‐Myc; it should be noted that both fusion proteins are expected to have relative electrophoretic mobility in the range 58–80 kDa. These results confirm the data obtained in the two‐hybrid system and indicate that the latter can serve as a reliable assay for VirE2–VIP1 interactions. Collectively, the data in Fig. 2 support the notion that C58 VirE2 can interact with numerous VIP1 homologues (i.e. bZIP52, bZIP69, posF21, bZIP29 and bZIP30), VIP1 and NtRSG in plant cells.

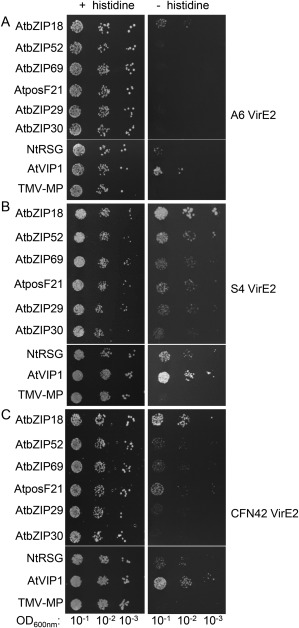

Next, we investigated whether VirE2 proteins encoded by other Agrobacterium and Rhizobium species/strains can interact with AtVIP1 and its homologues. Specifically, we selected virE2 sequences from the octopine‐type A. tumefaciens A6, Agrobacterium vitis S4 and Rhizobium etli CFN42, together with the nopaline‐type A. tumefaciens C58; these bacterial strains represent the major known examples of plant‐infecting bacteria containing a functional virulence region that can transfer T‐DNA to plants. Figure 3 shows that each of these VirE2 proteins has the ability to bind VIP1 and/or its homologues, but with different binding specificity. The yeast two‐hybrid analysis under stringent selection conditions in the presence of 0.1–5.0 mm 3‐AT demonstrated that A6 VirE2 had a relatively narrow specificity, detectibly interacting with bZIP18, VIP1 and NtRSG. In contrast, S4 VirE2 showed broad specificity, interacting with all tested VIP1 homologues, with the most prominent interactions observed with bZIP18, bZIP52, VIP1 and NtRSG; similarly, CFN42 VirE2 also interacted with all VIP1 homologues, except bZIP30, and, most prominently, with bZIP18 and VIP1 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, bZIP18, which interacted well with A6 VirE2, S4 VirE2 and CFN42 VirE2, was the only VIP1 homologue that was not recognized by C58 VirE2. Without selection, all combinations of the tested proteins resulted in comparable cell growth (Fig. 3). Thus, the ability to bind to VIP1 and its homologues appears to be conserved for VirE2 proteins from the four major representatives of known bacterial species/strains with functional T‐DNA transfer machineries, suggesting that it may represent a key aspect of their activity.

Figure 3.

Interaction of VirE2 proteins from different Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Rhizobium etli strains with AtVIP1 and its homologues. VirE2 proteins were fused to LexA and AtVIP1 and its homologues were fused to Gal4‐AD. (A) Agrobacterium tumefaciens A6 VirE2. Cells were grown in the presence of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT). (B) Agrobacterium vitis S4 VirE2. Cells were grown in the presence of 1.0 mm 3‐AT. (C) Rhizobium etli CFN42 VirE2. Cells were grown in the presence of 5.0 mm 3‐AT. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media. Two independent experiments were performed for each assay with similar results.

Transcription factor activity and subcellular localization of AtVIP1 homologues

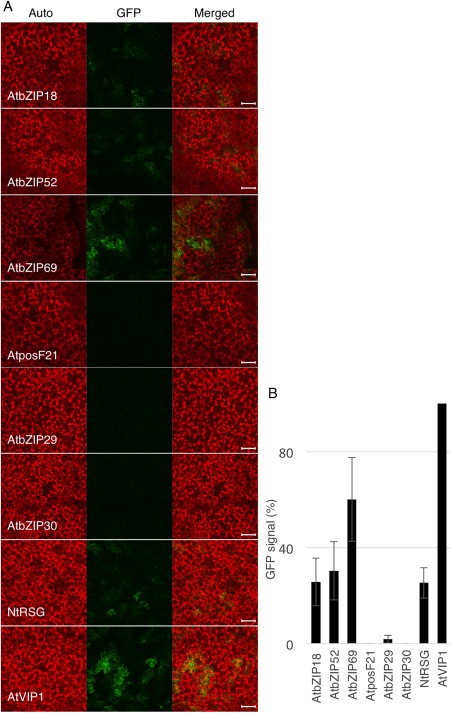

VIP1 is a transcription factor that regulates numerous genes involved mostly in stress and defence responses (Pitzschke et al., 2009) and in osmosensing (Tsugama et al., 2012). Although VIP1 homologues have been shown to possess similar transcriptional activation abilities in the osmosensory response (Tsugama et al., 2014), their potentially redundant activity in the activation of defence signalling regulatory sequences has not been examined. These sequences include a short DNA hexamer motif that acts as the VIP1 response element (VRE) (Pitzschke et al., 2009). To monitor VIP1 activation of VRE, we have developed a reporter system in which the direct tandem repeat of the VRE sequence is fused to the CaMV 35S minimal promoter that drives the expression of GFP (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2013a). Here, we took advantage of this system to measure the ability of VIP1 homologues to activate the VRE‐controlled reporter. Figure 4A shows that bZIP18, bZIP52, bZIP69 and NtRSG, as well as the positive control VIP1, induce VRE, resulting in GFP expression, whereas posF21, bZIP29 and bZIP30 lack this activity. That the endogenous VIP1 did not detectably activate GFP expression is consistent with the known naturally low levels of this protein in plant cells (Tzfira et al., 2001, 2002). The GFP signal induced by VIP1 homologues was then quantified relative to the induction by VIP1. Figure 4B shows that bZIP18, bZIP52, bZIP69 and NtRSG activate the VRE‐controlled reporter with efficiencies ranging from 20% to 50% of the activity observed with VIP1.

Figure 4.

Induction of VIP1 response element (VRE)‐controlled green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression by AtVIP1 and its homologues. (A) Confocal microscopy analysis of GFP expression in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves 3 days after co‐infiltration with two Agrobacterium strains carrying the VRE1–35Smin‐GFP reporter construct and a construct expressing AtVIP1 or its indicated homologues. The GFP signal is in green; plastid autofluorescence is in red. Images are single confocal sections, and are representative of images obtained in three infiltrations performed on three different leaves, with two images recorded per infiltration. Scale bars, 100 µm. (B) Quantification of the VRE1‐GFP reporter expression shown in (A). The GFP signal was quantified using LSM Pascal software (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) by measuring the total GFP fluorescence in one field inside the infiltration area with a low magnification objective (10×); all images used for fluorescence measurement were taken with the same settings. The basal signal measured in an area infiltrated with VRE1‐GFP alone was subtracted from the values measured for each experimental condition, and the signal obtained with AtVIP1 was set as 100%. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM) of n = 3 independent biological replicates (leaves).

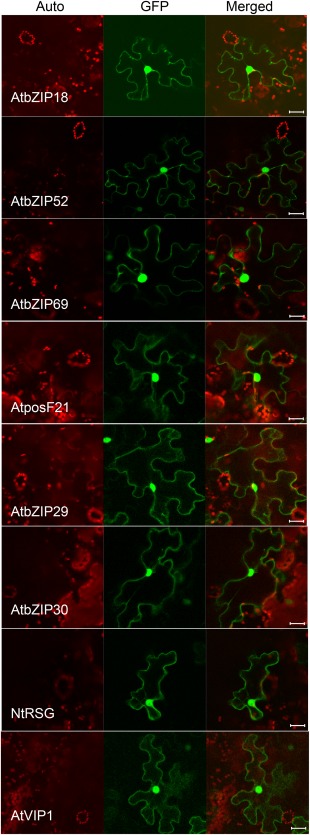

Unlike their effects on the induction of VRE, all VIP1 homologues displayed similar subcellular localization. Figure 5 shows that GFP‐tagged bZIP18, bZIP52, bZIP69, posF21, bZIP29, bZIP30 and NtRSG partitioned between the cell cytoplasm and the nucleus. The same nucleocytoplasmic distribution pattern was observed for the full‐length VIP1 protein here (Fig. 5) and in previous studies (Djamei et al., 2007; Tsugama et al., 2012). Thus, the similar subcellular localization patterns of these VIP1 homologues are consistent with their general functionality as transcription factors; yet, the specificity of their promoter response elements differs between different groups of the members of the family. Interestingly, these differences between the VIP1 homologues in their specificity of promoter recognition do not correlate with the differences in their ability to bind VirE2. Thus, the determinants that define the natural function of the VIP1 homologues in the regulation of gene expression probably differ from the determinants that define their interaction with VirE2 and possible involvement in Agrobacterium infection.

Figure 5.

AtVIP1 and its homologues localize to the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. The indicated proteins tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) were transiently expressed in agroinfiltrated leaf epidermis of Nicotiana benthamiana, and analysed by confocal microscopy at 3 days post‐infiltration. The GFP signal is in green; plastid autofluorescence is in red. Images are single confocal sections, representative of images obtained in two independent experiments performed for each protein; for each experiment, three infiltrations were performed on three different leaves, with two images recorded per infiltration. Scale bars, 20 µm.

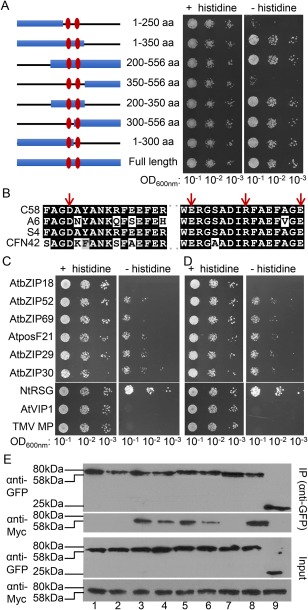

C58 VirE2 sequence determinants involved in binding to AtVIP1 and AtVIP1 homologues

Interaction between C58 VirE2 and AtVIP1 has been proposed to rely on two small central domains in the protein, i.e. amino acid residues 278–293 and 323–338, based on in vitro peptide interaction assays (Maes et al., 2014). To explore the role of these two domains further, we generated a series of deletion mutations (Fig. 6A), and tested them for the ability to interact with AtVIP1 and its homologues in the yeast two‐hybrid system, followed by validation of the resulting data by co‐immunoprecipitation. Initially, the mutants were tested for interaction with VIP1, and Fig. 6A shows that two mutants that did not contain the central domains, i.e. mutants 1–250 and 350–556, exhibited only residual levels of binding; these mutants were not toxic to yeast because, without selection, they allowed cell growth indistinguishable from that observed with other tested mutants. In contrast, the presence of both or either one of the central domains was sufficient for apparent wild‐type levels of interactions, virtually irrespective of the identity of the other VirE2 sequences present in each mutant (Fig. 6A). Amino acid sequence alignment of the two central domains between C58 VirE2, A6 VirE2, S4 VirE2 and CFN42 VirE2 showed an overall conservation, as well as the presence of a conserved FAGD/E motif in each of the domains (Fig. 6B). Based on this sequence analysis, we selected 12 amino acid residues, i.e. G280, D281, K286, F288, E290, W323, E324, R325, R331, F335, G337 and E338, conserved between the two central domains of all four bacterial strains/species and located within and outside the FAGD/E motifs; we also aimed to include charged amino acids that might be involved in protein–protein interactions. We used alanine scanning mutagenesis to substitute alanine for these 12 residues and produced a series of single, double, triple and quadruple combinations of such substitutions; the resulting mutants were tested for interaction with VIP1 in the yeast two‐hybrid system (Fig. S2, see Supporting Information).

Figure 6.

Interaction of C58 VirE2 mutants with AtVIP1 and its homologues. (A) A schematic summary of C58 VirE2 deletion mutants (left) and yeast two‐hybrid assay for interaction between the indicated C58 VirE2 mutants fused to LexA and AtVIP1 fused to Gal4‐AD (right). Numbers represent the positions of amino acid (aa) residues present in each mutant, and the two central domains are indicated with vertical ovals. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the presence of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT). (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the two central domains in C58 VirE2, A6 VirE2, S4 VirE2 and CFN42 VirE2. The residues mutated in the C58 VirE2 4M mutant, i.e. D281, E324, R331 and E338, are indicated with arrows. (C) Yeast two‐hybrid assay for C58 VirE2 4M interactions with AtVIP1 and its homologues. (D) Yeast two‐hybrid assay for C58 VirE2 350–556 interactions with AtVIP1 and its homologues. LexA‐C58 VirE2 4M or LexA‐C58 VirE2 350–556 was co‐expressed with Gal4‐AD fused to the indicated tested proteins. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the presence of 0.1 mm 3‐AT. (E) Co‐immunoprecipitation assay for C58 VirE2 4M interactions with AtVIP1 and its homologues. The experiment was performed using C58 VirE2 4M‐Myc, exactly as described in Fig. 2B for a similar assay with C58 VirE2‐Myc. Top panel: proteins immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti‐GFP antibody and analysed by western blotting with anti‐GFP antibody or anti‐Myc antibody. Bottom panel: total amounts of the tested proteins (Input) analysed by western blotting with anti‐GFP or anti‐Myc antibody without immunoprecipitation. Lane 1, AtbZIP18; lane 2, AtbZIP52; lane 3, AtbZIP69; lane 4, AtposF21; lane 5, AtbZIP29; lane 6, AtbZIP30; lane 7, NtRSG; lane 8, AtVIP1; lane 9, free green fluorescent protein (GFP). Two independent experiments were performed for each assay with similar results.

Most single, double and triple mutants retained some ability to interact with VIP1, although with different efficiency. For example, D281A, E324A and R331A, and most double or triple mutants that contained one of these mutations, showed reduced binding (Fig. S2). Remarkably, however, in one quadruple mutant of C58 VirE2, i.e. D281A/E324A/R331A/E338A (Fig. 6B, arrows), which was designated C58 VirE2 4M, the interaction with VIP1 was virtually abolished (Fig. S2). We then tested C58 VirE2 4M for its ability to interact with VIP1 homologues. Figure 6C shows that C58 VirE2 4M still interacted with bZIP52, bZIP69, posF21, bZIP29 and bZIP30, albeit relatively weakly compared with their interactions with the wild‐type C58 VirE2, whereas the interaction with NtRSG did not appear to be affected (compare Fig. 6C with Fig. 2A). A similar pattern of interactions was observed with the deletion mutant C58 VirE2 350–556 (Fig. 6D), suggesting that this C‐terminal segment of the protein, which lacks the two central domains required for binding to VIP1, probably contains sequences that allow the interaction with NtRSG and the five Arabidopsis VIP1 homologues, although there is no apparent sequence homology between the 350–556 segment of C58 VirE2 and any of the two central domains required for interaction with AtVIP1. As expected, VIP1, bZIP18 and TMV MP showed no interactions with C58 VirE2 4M or C58 VirE2 350–556, and growth under non‐selective conditions showed no effects of any of the tested protein combinations on cell viability (Fig. 6C,D). The pattern of C58 VirE2 4M interactions with VIP1 and its homologues was confirmed by co‐immunoprecipitation. Figure 6E shows that Myc‐tagged C58 VirE2 44M co‐expressed in N. benthamiana leaves with GFP‐tagged VIP1 or its different homologues, and immunoprecipitated with anti‐GFP antibody, co‐precipitated with bZIP52, bZIP69, posF21, bZIP29 and bZIP30, as detected by western blotting with anti‐Myc antibody (lanes 3–8), whereas no such co‐immunoprecipitation was observed for C58 VirE2 4M‐Myc co‐expressed with GFP‐VIP1, GFP‐bZIP18 or GFP‐TMV MP (lanes 1, 2 and 7). Taken together, these data support the idea of different C58 VirE2 sequence determinants involved in interactions with VIP1 and its homologues.

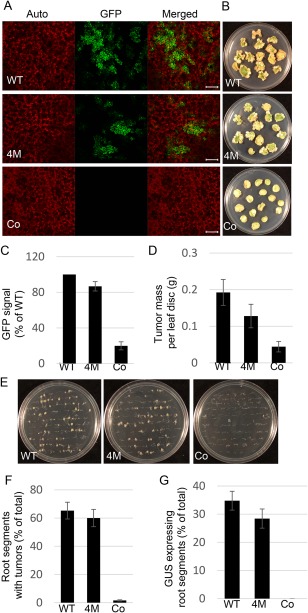

Finally, we examined the ability of C58 VirE2 4M to transform genetically Nicotiana and Arabidopsis tissues. To this end, we used the oncogenic Agrobacterium virE2 insertional mutant strain mx358, which does not express functional VirE2 (Stachel et al., 1985) and which was complemented with a construct expressing, from the native virE promoter, either the wild‐type C58 VirE2 or C58 VirE2 4M. In Nicotiana, transient genetic transformation was monitored in leaf tissues by the expression of a GFP reporter transgene, whereas stable transformation was monitored by the formation of tumours on inoculated leaf discs. In Arabidopsis, transient genetic transformation was monitored by the expression of a gus gene for the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) reporter in root segments and stable transformation was monitored by a root tumour assay (Gelvin, 2006). Figure 7A shows that both C58 VirE2 and C58 VirE2 4M allowed transient expression of the GFP transgene in Nicotiana leaves, with no such expression observed with a control construct lacking the virE2 gene. Both C58 VirE2 and C58 VirE2 4M also complemented the bacterial tumorigenicity, whereas no tumours were observed with the control plasmid, i.e. in the absence of VirE2 (Fig. 7B). Quantification of these data by measurement of the GFP signal and weighing the tumours suggested that C58 VirE2 4M exhibited a slightly lower transformation efficiency (Fig. 7C,D), but these differences were not statistically significant, with P > 0.05. The values obtained with the control plasmid were low, and they represented the background readings of each quantification method. Similarly, we did not detect statistically significant differences between C58 VirE2 and C58 VirE2 4M in their ability to complement the bacterial capacity for transient and stable transformation of Arabidopsis roots (Fig. 7E–G). These data are consistent with our observations that the 4M mutation, although blocking the VirE2 interaction with VIP1, has no effect on its interactions with Nicotiana NtRSG or with five Arabidopsis VIP1 homologues (see Fig. 6C).

Figure 7.

The effect of C58 VirE2 4M on the transient and stable transformation capacity of Agrobacterium. (A) Transient transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Plant tissues were co‐infiltrated with two cultures of the Agrobacterium strain mx358 which lacks its endogenous virE2 gene: one harbouring a plasmid that expresses either wild‐type C58 VirE2 (pEpA6‐C58virE2) or C58 VirE2 4M (pEpA6‐C58virE2–4M) in the bacterium, or carries an empty plasmid (pEpA6), and the other harbouring a binary plasmid that expresses the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter. At 3 days post‐infiltration, GFP expression in the inoculated tissues was analysed by confocal microscopy. The GFP signal is in green; plastid autofluorescence is in red. Images are single confocal sections, representative of images obtained in two independent experiments performed for each protein; for each experiment, three infiltrations were performed on three different leaves, with two images recorded per infiltration. Scale bars, 100 µm. (B) Stable transformation of Nicotiana tabacum leaves. Leaf discs were inoculated with the Agrobacterium strain mx358 with a plasmid that expresses either wild‐type C58 VirE2 (pEpA6‐C58virE2) or C58 VirE2 4M (pEpA6‐C58virE2–4M), or carries an empty plasmid (pEpA6), and the tumors were photographed 3 weeks after inoculation. Three plates, each containing 15 leaf discs, were used for each condition. (C) Quantification of GFP expression shown in (A). GFP signal was quantified as described in Fig. 4. Signal obtained with wild‐type C58 VirE2 was set as 100%. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) of n = 3 independent biological replicates (leaves). (D) Quantification of tumor formation shown in (B). Tumors were scored by their mass. Error bars represent SEM of n = 3 independent biological replicates (plates). (E) Stable transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Root segments were inoculated with the Agrobacterium strain mx358 with a plasmid that expresses either wild‐type C58 VirE2 (pEpA6‐C58virE2) or C58 VirE2 4M (pEpA6‐C58virE2–4M), or carries an empty plasmid (pEpA6), and the tumors were photographed 3 weeks after inoculation. Three plates, each containing 50 root segments, were used for each condition. (F) Quantification of tumor formation shown in (E). Root segments with tumors were counted and expressed as a percentage of the total inoculated roots. Error bars represent SEM of n = 3 independent biological replicates (plates). (G) Transient transformation of A. thaliana roots. Root segments were inoculated with two cultures of the Agrobacterium strain mx358: one with a plasmid expressing wild‐type C58 VirE2 (pEpA6‐C58virE2) or C58 VirE2 4M (pEpA6‐C58virE2–4M), or carrying an empty plasmid (pEpA6), and the other harbouring a binary plasmid expressing the β‐glucuronidase (GUS) reporter. At 3 days post‐inoculation, GUS activity in the inoculated tissues was analysed by histochemical staining, and the number of stained roots was counted and expressed as a percentage of the total inoculated roots. Three plates, each containing 50 root segments, were used for each condition. WT, wild‐type C58 VirE2; 4M, C58 VirE2 4M; Co, empty vector.

Discussion

The proposed involvement of the Arabidopsis bZIP protein VIP1 in Agrobacterium infection is consistent with its known roles in different types of biotic and abiotic stress (Djamei et al., 2007; Pitzschke et al., 2009; Tsugama et al., 2014, 2016). Yet, a recent study has suggested that a loss‐of‐function mutant of VIP1 is still susceptible to infection (Shi et al., 2014). One possible explanation is the redundant function of one or more of the 75 members of the large bZIP family, especially the six proteins that belong to the VIP1 subgroup. Thus, it was important to examine possible interactions of VirE2 with these VIP1 homologues. Indeed, our data demonstrate that, in addition to VIP1, VirE2 from a nopaline‐type pTi58 plasmid interacts with five Arabidopsis VIP1 homologues as well as with a homologue from tobacco. Importantly, the ability to interact with the members of the VIP1 family is conserved between VirE2 proteins from such diverse bacteria as nopaline‐ and octopine‐type A. tumefaciens C58 and A6, A. vitis S4 and R. etli CFN42, all of which encode a functional protein machinery for T‐DNA transfer to plants. This conserved capability of recognition of VIP1‐like proteins on the pathogen side is complemented by the conserved nature of the VIP1‐like proteins on the host plant side, at least amongst the angiosperms.

The observation that the T‐DNA transfer capacity parallels the preservation of the VirE2‐VIP1 interaction across different bacterium–host strains/species and that the VirE2‐VIP1 interaction is ‘degenerate’, i.e. the same VirE2 protein has evolved to interact with multiple VIP1 homologues in the same host, suggest a role for this interaction in the genetic transformation mechanism. However, specific VirE2 proteins showed different, yet overlapping, specificities towards individual VIP1 homologues, potentially affecting the host range of the different bacterial species. This subset of VIP1 homologues shares somewhat redundant biological functions in uninfected cells (Tsugama et al., 2014, 2016; Van Leene et al., 2016), which suggests that this redundancy could also apply to their interactions with VirE2 during the infection process. Whereas, in nature, the host range of Agrobacterium is essentially limited to dicotyledonous plants, under laboratory conditions, many more eukaryotic species can be transformed by Agrobacterium, from monocotyledonous plants, to yeast and other fungi, to mammalian cultured cells (Lacroix et al., 2006). As at least some of these species do not encode a close homologue of VIP1, most probably they are transformed via alternative (and potentially less efficient) pathways, which may, in part, explain the low efficiency of genetic transformation of mammalian cells by the wild‐type T‐DNA transfer machinery (Kunik et al., 2001) or of plant cells by a VirE2‐deficient T‐DNA transfer machinery (Horsch et al., 1986; Stachel and Nester, 1986).

The degeneracy of the VirE2–VIP1 interaction was also manifested in different and mutually independent VirE2 determinants involved in interactions with different VIP1 homologues, such that a VirE2 mutant that does not bind VIP1 still interacts with other members of this family. Specifically, for the interaction of C58 VirE2 with VIP1, one of the two conserved central domains of VirE2 was necessary and sufficient, but did not appear to be involved in binding to VIP1 homologues. Furthermore, a truncated mutant corresponding to the C‐terminal half of the protein and lacking the two central domains retained the ability to interact with VIP1 homologues, indicating that this part of VirE2 contains another domain responsible for these interactions, although we were unable to detect conserved motifs in this sequence.

The nucleocytoplasmic localization of the Arabidopsis homologues of VIP1 was similar to that of VIP1 itself, consistent with their presumably similar biological roles of transcriptional regulators. Yet, they differed from VIP1 in their ability to recognize the VIP1 response element VRE and to induce reporter expression, with no clear correlation with their common ability to interact with VirE2. This suggests that different domains of the VIP1 homologues are involved in these two different activities, and that the VIP1 functionality related to the interaction with VirE2 is independent of its function as a transcriptional regulator.

Collectively, the almost ubiquitous ability to interact with VirE2 amongst VIP1 homologues, the involvement of different VirE2 domains in interactions with different VIP1 homologues and the relative independence of these interactions on the specificity of VIP1 homologues as transcriptional activators suggest that this functionality is deeply ingrained into the process of Agrobacterium infection. Indeed, mutations that completely abolished the C58 VirE2 ability to interact with VIP1 produced no statistically significant effect on interactions with VIP1 homologues, Arabidopsis or Nicotiana, or on the efficiency of the transient and stable genetic transformation of these plants. This preservation of the VirE2‐VIP1 interaction across different bacterial species/strains and different VIP1 homologues makes the alternative explanation that this interaction is not involved in transformation unlikely, yet it cannot be ruled out. In addition, infection assays performed under laboratory conditions could influence the efficiency and the lack of requirements for the VirE2‐VIP1 interaction. Thus, it would be particularly interesting to understand whether interactions of VirE2 with VIP1 homologues might affect the host range of the different Agrobacterium strains and/or influence the efficiency of transformation of a given host plant species in nature.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and cultures

Wild‐type Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains A6 (octopine‐type) and C58 (nopaline‐type), Agrobacterium vitis S4 (a kind gift from Dr Thomas J. Burr, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA) and Rhizobium etli CFN42 (kindly provided by Dr Russell Carlson, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA) were used for plasmid extraction and cloning of the virE2 coding sequences. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105, a disarmed C58 derivative harbouring the pMP90 helper plasmid, and the mx358 virE2 insertional mutant in the A348 background (Stachel et al., 1985) were used for N. benthamiana leaf infiltration and tobacco leaf disc or Arabidopsis root transformation experiments. All A. tumefaciens strains were grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 28 °C; R. etli was grown in TY medium (5 g/L tryptone, 3 g/L yeast extract and 10 mm CaCl2) at 28 °C. The E. coli strain DH5α was used for molecular cloning and grown in LB medium at 37 °C.

Plants

Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in soil. Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Col‐0) plants were grown on MS‐based medium (0.5 g/L MES, 10 g/L sucrose, 8 g/L agar, pH 5.8) after seed surface sterilization. Nicotiana tabacum var. Turk plants were micropropagated in vitro on high‐sucrose MS medium (0.5 g/L MES, 30 g/L sucrose, 8 g/L agar, pH 5.8). All plants were grown in environment‐controlled growth chambers under long‐day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark cycle at 140 µE/s/m2 light intensity) at 22 °C.

Protein sequence analyses

Homologues of the AtVIP1 sequences in plant species were identified in sequence databases using the blastp program (PubMed); for each species, the sequence with the highest score was selected. The VIP1 homologue phylogenetic tree was generated using MEGA version 6 (Tamura et al., 2013). Protein sequence alignments were performed with the T‐Coffee (Notredame et al., 2000) and Boxshade programs.

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis

Plasmids and cloning strategies are described in Table S2 (see Supporting Information), and primer sequences used in these cloning procedures are summarized in Table S3 (see Supporting Information). For Gal4‐AD fusions, the coding sequences of VIP1, VIP1 homologues and TMV MP were PCR amplified, using total A. thaliana Col‐0 cDNA as substrate, and cloned into the indicated sites of pGAD424 (LEU2+; Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). For LexA fusions, the coding sequences of virE2 and its mutant variants were PCR amplified, using purified Ti‐plasmids from the corresponding Agrobacterium or Rhizobium strains, and cloned into the indicated sites of pSTT91 (TRP1+) (Sutton et al., 2001). To generate point mutations in C58 virE2, overlapping PCRs with the indicated primers were carried out to introduce codon substitutions. Two DNA segments were amplified by PCR: from the translation initiation codon at the 5′‐end to the target codon position and from the target codon position to the 3′‐end of the coding sequence. For example, to introduce the D281A mutation, PCRs were performed with the primer pairs 8F‐17R and 17F‐8R (Table S3). The two PCR products were then used as template to generate the full‐length mutated virE2 sequence by overlapping PCR with the primer pair 8F‐8R, followed by insertion of the resulting PCR product, which encodes the full‐length C58 VirE2 D281A mutant, into the BamHI/PstI site of plasmid pSTT91, resulting in pSTT91‐C58virE2‐D281A (Table S2). For co‐immunoprecipitation, C58 virE2 and C58 virE2 4M coding sequences were PCR amplified and inserted into the HindIII‐KpnI sites of pSAT5‐Myc‐N1 (Magori and Citovsky, 2011). For expression in plants, the coding sequences of VIP1 and its homologues were inserted into the indicated sites of pSAT5A‐MCS (Tzfira et al., 2005) to be used in transcriptional activation experiments, or pSAT5‐GFP‐C1 (Tzfira et al., 2005) to be used in subcellular localization experiments. The resulting expression cassettes were excised with ICeuI and transferred into the same site of the binary pPZP‐RCS2 vector (Tzfira et al., 2005). The binary plasmid pCB302T‐VRE1‐GFP for VIP1‐induced expression of the GFP reporter has been described previously (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2013a). For expression in Agrobacterium cells, the full virE promoter was amplified from pTiA6 with the primer pair F29/R29 and introduced into the BspHI(NcoI)/EcoRI sites of pEp (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2011), producing pEpA6. Then, the coding sequences of C58 VirE2 and C58 virE2 4M were amplified from pSTT91‐C58virE2 or pSTT‐C58virE2–4M, respectively, with the primer pair F30/R30, and cloned into the NheI/KpnI sites of pEpA6. For the monitoring of transient T‐DNA expression in Arabidopsis roots and tobacco leaf discs, we used binary plasmids pBISN1 with an expression cassette for a gus reporter gene with a plant intron sequence (gus‐int) (Narasimhulu et al., 1996), and pCB302T‐GFP carrying an expression cassette for EGFP (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2016), respectively.

Yeast two‐hybrid protein interaction assay

The assay was performed using the yeast strain L40 (Hollenberg et al., 1995), co‐transformed with pSTT91‐ and pGAD424‐derived constructs expressing the tested protein pairs. Five to ten colonies obtained on plates with synthetic defined premixed yeast growth medium (TaKaRa Clontech Mountain View, CA, USA) lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD‐Leu‐Trp) were resuspended in water and plated at the indicated dilutions on SD‐Leu‐Trp and on the same medium lacking leucine, tryptophan and histidine (SD‐Leu‐Trp‐His) supplemented with the indicated concentrations of 3‐AT. Cell growth was recorded after incubation for 2–3 days at 28 °C.

Co‐immunoprecipitation

Co‐immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described by Magori and Citovsky (2011), with some modifications. Briefly, the tagged proteins were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves after agroinfiltration, as described previously (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2011) and, after 72 h, infiltrated leaves were harvested and ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Total proteins were extracted from the ground tissues in immunoprecipitation buffer [50 mm Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% NP‐40, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 3 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 × plant protease inhibitor cocktail (Amresco Solon, OH, USA)]. Protein extracts were incubated with anti‐GFP antibody (Clontech, dilution 1 : 250) for 3 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with Protein G‐Sepharose 4B (Invitrogen Grand Island, NY, USA) for an additional 3 h at 4 °C to capture and precipitate the immune complexes. After three washes with washing buffer (50 mm Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% NP‐40 and 1 mm EDTA), immunoprecipitates were eluted in sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) sample buffer and subjected to western blot analysis. GFP‐ and My‐tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti‐GFP antibody (Clontech, dilution 1 : 2000) and anti‐cMyc antibody (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ, USA, dilution 1 : 2000), respectively, followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, dilution 1 : 2000).

Agroinfiltration and confocal microscopy

For agroinfiltration, the Agrobacterium strain EHA105 (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2013a) harbouring the appropriate binary constructs was grown overnight at 25 °C, diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3, and infiltrated into intact N. benthamiana leaves as described previously (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2011). The leaves were harvested 3 days after agroinfiltration and analysed under a Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) LSM 5 Pascal confocal laser scanning microscope. Three plants were used for each experimental condition, and all experiments were repeated at least three times.

Transient and stable transformation assays

Transient expression assays in N. benthamiana were performed exactly as described previously (Lacroix and Citovsky, 2011). Tumour assays in N. tabacum leaf discs were performed following the classical leaf disc transformation procedure (Horsch et al., 1985). An overnight culture of A. tumefaciens in LB supplemented with antibiotics was diluted in LB without antibiotics, grown for 3–4 h and adjusted to a cell density of OD600 = 0.5. Leaf discs (9 mm) from fully expanded leaves of 4‐week‐old tobacco plants were immersed for 10 min in the Agrobacterium suspension culture, placed on MS medium and incubated for 48 h in a growth chamber. Leaf discs were then rinsed in sterile water with 100 mg/L timentin, placed on MST medium (MS supplemented with 300 mg/L timentin) and incubated for 3 weeks, after which the weight of the tumours was recorded.

Transient and stable Arabidopsis root transformation assays were performed as described previously (Gelvin, 2006). Root bundles of 14‐day‐old Arabidopsis seedlings, aseptically grown on MS medium, were collected, cut into 0.5‐cm‐long segments and transferred onto MS medium. Root segment bundles were covered with approximately 0.5 mL of bacterial suspension (OD600 = 0.1). After a 10‐min incubation, the excess of bacterial suspension was removed by pipetting, and the plates were placed in a growth chamber (22 °C, long‐day conditions) for 2 days. The root segments were then rinsed three times in sterile water with 100 mg/L timentin. For GUS histochemical staining, root segments were incubated on MST medium (MS supplemented with 300 mg/L timentin) for 3 days, transferred into a GUS staining solution (50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 15 mm EDTA, 0.1% Tween 20, 10 g/L 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl‐beta‐D‐glucuronic acid, cyclohexylammonium salt (X‐Gluc)) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. For tumorigenesis assays, the roots were transferred onto MST plates and incubated for 3 weeks before observation.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Fig. S1 Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) movement protein (MP) does not interact with AtVIP1 and its homologues. Yeast two‐hybrid interaction assay. LexA‐C58 TMV MP was co‐expressed with Gal4‐AD fused to the indicated tested proteins. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT).

Fig. S2 Interaction of C58 VirE2 alanine scanning mutants with AtVIP1. Yeast two‐hybrid interaction assay. The indicated C58 VirE2 mutants fused to LexA were co‐expressed with AtVIP1 fused to Gal4‐AD. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the presence of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT). WT, wild‐type C58 VirE2.

Table S1 Protein identifiers (ID) and amino acid sequences of the AtVIP1 homologues used to construct the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1.

Table S2 Plasmids and cloning strategies.

Table S3 Primer sequences.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Thomas J. Burr (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA) and Dr Russell Carlson (University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA) for the kind gifts of Agrobacterium vitis S4 and Rhizobium etli CFN42, respectively, as well as Dr Stanton B. Gelvin (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA) for the pBISN1 plasmid. The work in V.C.'s laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (GM50224), National Science Foundation (NSF) (MCB 1118491), US Department of Agriculture/National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA/NIFA) (2013‐02918) and US‐Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund (BARD) (IS‐4605‐13C) to V.C. L.W. is supported by the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences Independent Innovation Project (CX(15)1004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471812; 31672075) and the China Scholarship Council (No. 201506850021).

Contributor Information

Benoît Lacroix, Email: benoit.lacroix@stonybrook.edu.

Jianhua Guo, Email: jhguo@njau.edu.cn.

References

- Abu‐Arish, A. , Frenkiel‐Krispin, D. , Fricke, T. , Tzfira, T. , Citovsky, V. , Wolf, S.G. and Elbaum, M. (2004) Three‐dimensional reconstruction of Agrobacterium VirE2 protein with single‐stranded DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25 359–25 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie, P.J. , Ward, J.E. , Winans, S.C. and Nester, E.W. (1988) The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virE2 gene product is a single‐stranded‐DNA‐binding protein that associates with T‐DNA. J. Bacteriol. 170, 2659–2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky, V. , Wong, M.L. and Zambryski, P.C. (1989) Cooperative interaction of Agrobacterium VirE2 protein with single stranded DNA: implications for the T‐DNA transfer process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 1193–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky, V. , Knorr, D. , Schuster, G. and Zambryski, P.C. (1990) The P30 movement protein of tobacco mosaic virus is a single‐strand nucleic acid binding protein. Cell, 60, 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky, V. , Guralnick, B. , Simon, M.N. and Wall, J.S. (1997) The molecular structure of Agrobacterium VirE2‐single stranded DNA complexes involved in nuclear import. J. Mol. Biol. 271, 718–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky, V. , Kapelnikov, A. , Oliel, S. , Zakai, N. , Rojas, M.R. , Gilbertson, R.L. , Tzfira, T. and Loyter, A. (2004) Protein interactions involved in nuclear import of the Agrobacterium VirE2 protein in vivo and in vitro . J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29 528–29 533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djamei, A. , Pitzschke, A. , Nakagami, H. , Rajh, I. and Hirt, H. (2007) Trojan horse strategy in Agrobacterium transformation: abusing MAPK defense signaling. Science, 318, 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. (1985) Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution, 39, 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin, S.B. (2003) Agrobacterium‐mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the “gene‐jockeying” tool. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 16–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelvin, S.B. (2006) Agrobacterium transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana roots: a quantitative assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 343, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg, S.M. , Sternglanz, R. , Cheng, P.F. and Weintraub, H. (1995) Identification of a new family of tissue‐specific basic helix‐loop‐helix proteins with a two‐hybrid system. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 3813–3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch, R.B. , Fry, J.E. , Hoffman, N.L. , Eichholtz, D.A. , Rogers, S.G. and Fraley, R.T. (1985) A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science, 227, 1229–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsch, R.B. , Klee, H.J. , Stachel, S. , Winans, S.C. , Nester, E.W. , Rogers, S.G. and Fraley, R.T. (1986) Analysis of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence mutants in leaf discs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 2571–2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby, M. , Weisshaar, B. , Dröge‐Laser, W. , Vicente‐Carbajosa, J. , Tiedemann, J. , Kroj, T. and Parcy, F. (2002) bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis . Trends Plant Sci. 7, 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunik, T. , Tzfira, T. , Kapulnik, Y. , Gafni, Y. , Dingwall, C. and Citovsky, V. (2001) Genetic transformation of HeLa cells by Agrobacterium . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 1871–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B. and Citovsky, V. (2011) Extracellular VirB5 enhances T‐DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to the host plant. PLoS One, 6, e25578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B. and Citovsky, V. (2013a) Characterization of VIP1 activity as a transcriptional regulator in vitro and in planta . Sci. Rep. 3, 2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B. and Citovsky, V. (2013b) The roles of bacterial and host plant factors in Agrobacterium‐mediated genetic transformation. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 57, 467–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B. and Citovsky, V. (2016) A functional bacterium‐to‐plant DNA transfer machinery of Rhizobium etli . PLOS Pathog. 12, e1005502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B. , Tzfira, T. , Vainstein, A. and Citovsky, V. (2006) A case of promiscuity: Agrobacterium's endless hunt for new partners. Trends Genet. 22, 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B. , Loyter, A. and Citovsky, V. (2008) Association of the Agrobacterium T‐DNA‐protein complex with plant nucleosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 15 429–15 434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loyter, A. , Rosenbluh, J. , Zakai, N. , Li, J. , Kozlovsky, S.V. , Tzfira, T. and Citovsky, V. (2005) The plant VirE2 interacting protein 1. A molecular link between the Agrobacterium T‐complex and the host cell chromatin? Plant Physiol. 138, 1318–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes, M. , Amit, E. , Danieli, T. , Lebendiker, M. , Loyter, A. and Friedler, A. (2014) The disordered region of Arabidopsis VIP1 binds the Agrobacterium VirE2 protein outside its DNA‐binding site. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 27, 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magori, S. and Citovsky, V. (2011) Agrobacterium counteracts host‐induced degradation of its F‐box protein effector. Sci. Signal. 4, ra69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhulu, S.B. , Deng, X.B. , Sarria, R. and Gelvin, S.B. (1996) Early transcription of Agrobacterium T‐DNA genes in tobacco and maize. Plant Cell, 8, 873–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame, C. , Higgins, D.G. and Heringa, J. (2000) T‐Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzschke, A. , Djamei, A. , Teige, M. and Hirt, H. (2009) VIP1 response elements mediate mitogen‐activated protein kinase 3‐induced stress gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 18 414–18 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou, N. and Nei, M. (1987) The neighbor‐joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen, P. , Pazour, G.J. , Anderson, D. and Das, A. (1989) Cooperative binding of Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirE2 protein to single‐stranded DNA. J. Bacteriol. 171, 2573–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Lee, L.Y. and Gelvin, S.B. (2014) Is VIP1 important for Agrobacterium‐mediated transformation? Plant J. 79, 848–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachel, S.E. and Nester, E.W. (1986) The genetic and transcriptional organization of the vir region of the A6 Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium . EMBO J. 5, 1445–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachel, S.E. , An, G. , Flores, C. and Nester, E.W. (1985) A Tn3 lacZ transposon for the random generation of beta‐galactosidase gene fusions: application to the analysis of gene expression in Agrobacterium . EMBO J. 4, 891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, A. , Heller, R.C. , Landry, J. , Choy, J.S. , Sirko, A. and Sternglanz, R. (2001) A novel form of transcriptional silencing by Sum1–1 requires Hst1 and the origin recognition complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 3514–3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K. , Stecher, G. , Peterson, D. , Filipski, A. and Kumar, S. (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugama, D. , Liu, S. and Takano, T. (2012) A bZIP protein, VIP1, is a regulator of osmosensory signaling in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiol. 159, 144–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugama, D. , Liu, S. and Takano, T. (2014) Analysis of functions of VIP1 and its close homologs in osmosensory responses of Arabidopsis thaliana . PLoS One, 9, e103930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsugama, D. , Liu, S. and Takano, T. (2016) The bZIP protein VIP1 is involved in touch responses in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 171, 1355–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira, T. , Vaidya, M. and Citovsky, V. (2001) VIP1, an Arabidopsis protein that interacts with Agrobacterium VirE2, is involved in VirE2 nuclear import and Agrobacterium infectivity . EMBO J. 20, 3596–3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira, T. , Vaidya, M. and Citovsky, V. (2002) Increasing plant susceptibility to Agrobacterium infection by overexpression of the Arabidopsis VIP1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 10 435–10 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira, T. , Vaidya, M. and Citovsky, V. (2004) Involvement of targeted proteolysis in plant genetic transformation by Agrobacterium . Nature, 431, 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzfira, T. , Tian, G.W. , Lacroix, B. , Vyas, S. , Li, J. , Leitner‐Dagan, Y. , Krichevsky, A. , Taylor, T. , Vainstein, A. and Citovsky, V. (2005) pSAT vectors: a modular series of plasmids for fluorescent protein tagging and expression of multiple genes in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 57, 503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Leene, J. , Blomme, J. , Kulkarni, S.R. , Cannoot, B. , De Winne, N. , Eeckhout, D. , Persiau, G. , Van De Slijke, E. , Vercruysse, L. , Vanden Bossche, R. and Heyndrickx, K.S. (2016) Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis transcription factor bZIP29 reveals its role in leaf and root development. J. Exp. Bot, 67, 5825–5840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E. and Barnes, W. (1988) VirD2 protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens very tightly linked to the 5′ end of T‐strand DNA. Science, 242, 927–930. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S. , Deom, C.M. , Beachy, R.N. and Lucas, W.J. (1989) Movement protein of tobacco mosaic virus modifies plasmodesmatal size exclusion limit. Science, 246, 377–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, C. and Nester, E.W. (1988) Association of the VirD2 protein with the 5′ end of T‐strands in Agrobacterium tumefaciens . J. Bacteriol. 170, 3367–3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaltsman, A. , Krichevsky, A. , Loyter, A. and Citovsky, V. (2010) Agrobacterium induces expression of a plant host F‐box protein required for tumorigenicity. Cell Host Microbe, 7, 197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaltsman, A. , Lacroix, B. , Gafni, Y. and Citovsky, V. (2013) Disassembly of synthetic Agrobacterium T‐DNA‐protein complexes via the host SCFVBF ubiquitin‐ligase complex pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 169–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl, E. and Pauling, L. (1965) Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins In: Evolving Genes and Proteins (Bryson V. and Vogel H. J., eds), pp. 97–166. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Fig. S1 Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) movement protein (MP) does not interact with AtVIP1 and its homologues. Yeast two‐hybrid interaction assay. LexA‐C58 TMV MP was co‐expressed with Gal4‐AD fused to the indicated tested proteins. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the absence (left) or presence (right) of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT).

Fig. S2 Interaction of C58 VirE2 alanine scanning mutants with AtVIP1. Yeast two‐hybrid interaction assay. The indicated C58 VirE2 mutants fused to LexA were co‐expressed with AtVIP1 fused to Gal4‐AD. The indicated dilutions of cell cultures were plated and grown on non‐selective (+histidine) and selective (–histidine) media in the presence of 0.1 mm 3‐amino‐1,2,4‐triazole (3‐AT). WT, wild‐type C58 VirE2.

Table S1 Protein identifiers (ID) and amino acid sequences of the AtVIP1 homologues used to construct the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1.

Table S2 Plasmids and cloning strategies.

Table S3 Primer sequences.