Abstract

Aims

GSK3191607, a novel inhibitor of the Plasmodium falciparum ATP4 (PfATP4) pathway, is being considered for development in humans. However, a key problem encountered during the preclinical evaluation of the compound was its inconsistent pharmacokinetic (PK) profile across preclinical species (mouse, rat and dog), which prevented reliable prediction of PK parameters in humans and precluded a well‐founded assessment of the potential for clinical development of the compound. Therefore, an open‐label microdose (100 μg, six subjects) first time in humans study was conducted to assess the human PK of GSK3191607 following intravenous administration of [14C]‐GSK3191607.

Methods

A human microdose study was conducted to investigate the clinical PK of GSK3191607 and enable a Go/No Go decision on further progression of the compound. The PK disposition parameters estimated from the microdose study, combined with preclinical in vitro and in vivo pharmacodynamic parameters, were all used to estimate the potential efficacy of various oral dosing regimens in humans.

Results

The PK profile, based on the microdose data, demonstrated a half‐life (~17 h) similar to other antimalarial compounds currently in clinical development. However, combining the microdose data with the pharmacodynamic data provided results that do not support further clinical development of the compound for a single dose cure.

Conclusions

The information generated by this study provides a basis for predicting the expected oral PK profiles of GSK3191607 in man and supports decisions on the future clinical development of the compound.

Keywords: clinical research, drug development, malaria, microdose, pharmacokinetic, phase 0

What is Already Known about this Subject

Microdose studies in drug development can be cost effective as they provide a pharmacokinetic readout before committing to the more expensive studies.

The linear extrapolation of pharmacokinetics from microdose to therapeutic doses has been shown in literature to apply especially when considering the intravenous route.

What this Study Adds

The information generated by this intravenous dose microdose study provided support for termination of the clinical development of GSK3191607 by the oral route of administration based on the short half‐life for a single dose.

The study is an example of using microdosing to enable progression or termination (Go/No Go) decisions in drug development when the preclinical information alone does not allow such decisions to be made with confidence.

Introduction

Malaria is a major global disease caused by the protozoan parasite Plasmodium, and is transmitted by infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Plasmodium falciparum is accountable for the highest mortality in malaria whereas Plasmodium vivax is associated with high morbidity. Half of the world's population are at risk of malaria and in 2015 there were around 212 million cases of malaria and approximately 400 000 deaths 1.

The effectiveness of current antimalarial therapy is under continuous threat through the spread of resistant Plasmodium strains, and even the most recent class of antimalarial drugs used in the current standard‐of‐care regimens (ACT: artemisinin combination therapies) are now showing evidence of clinical failure 2, 3, 4, 5. Consequently, there is a clear and urgent need to identify new therapies with a novel mechanism of action. Such new treatments must be efficacious against current resistant strains, display a rapid onset of antimalarial effects and demonstrate activity against different stages of parasite lifecycle.

New potential antimalarial leads have been discovered by phenotypic screening, which involves testing compounds for their activity directly against the Plasmodium parasite in vitro 6, 7, 8. By use of high throughput screening methodology, approximately two million compounds from the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) corporate collection were screened for activity against blood stages of P. falciparum. Over 13 533 potential antimalarial hits were identified and recently published as the Tres Cantos Antimalarial Set (TCAMS) 9. To identify antimalarials with the potential to block the transmission of malaria, a new assay capable of screening compounds for their inhibitory activity against mature gametocytes was also developed and used to screen the TCAMS compounds 10. This screening strategy is expected to enhance the identification of molecules that have the best chance of achieving efficacy against malaria while also having a lower risk of attrition during development.

As a result of the above screens, the quinazolinedione compound series emerged as a promising family with dual activity – both against blood stages of the parasite (schizonticidal) and against mature gametocytes (gametocytocidal). After a lead optimization effort, GSK3191607, from this series, was identified for possible progression into humans due to its excellent in vitro and in vivo (P. falciparum mouse model) potency as well as other qualities favourable to drug development (GSK data on file). It displayed a novel, but already clinically proven mechanism of action – inhibition of the PfATP4 pathway, which has been implicated in the regulation of sodium homeostasis in the parasite P. falciparum 11, 12, 13, 14. No PfATP4 inhibitors are yet approved for clinical use, although some are in development 14, 15, 16.

GSK3191607 had not been administered in humans prior to the current study. Studies of GSK3191607 in the mouse, rat and dog (GSK data on file) showed inconsistency in the PK profiles across the species studied. As a result, various methods of allometric scaling of the preclinical pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters produced a wide range of predicted values for humans (Table 1). Notably, the predicted terminal elimination half‐life of GSK3191607 in humans varied from as short as 2 h to close to 300 h. A very short half‐life in humans (e.g. 2–5 h) would make the compound unsuitable for progression into clinical development due to high risk of therapeutic failure as a consequence of insufficient systemic exposure upon once daily administration in a standard 3‐day course of antimalarial therapy. As an example, KAE609 (Cipargamin), a compound with the same mechanism of action, is considered appropriate for a 3‐day treatment course based on its half‐life of 20.8 h (range 11.3–37.6 h) 14, 15. By contrast, a long half‐life (e.g. >96 h, two parasite life cycles) may result in sufficient exposure for efficacy after only a single dose – a highly desirable profile for a new antimalarial drug. The extremely wide range of predicted half‐lives for GSK3191607 in humans, spanning the spectrum from unsuitable for clinical development to highly desirable, precluded an informed decision on progression of the compound. Furthermore, it was deemed unlikely that additional preclinical work would allow prediction of human PK parameters, including half‐life, with a greater confidence. As a result, a human microdose study was conducted to investigate the clinical PK of GSK3191607 and enable a Go/No Go decision on further progression of the compound based on knowledge of its actual half‐life in humans. A microdose study can achieve these objectives while being associated with reduced risk to the human subjects, reduced animal use and drug requirements as compared to a conventional approach to first time in human 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. In addition, this approach considerably reduces the investment of effort and funds into the costly and extensive good laboratory practise (GLP) toxicology package required to support a conventional first time in human study by requiring only a single dose GLP study in rodents, and therefore, it can subsequently allow for such an investment to be avoided altogether if a No Go decision is made. The decision was made to conduct this study using intravenous (IV) administration of GSK3191607 for reasons discussed later.

Table 1.

Scaled pharmacokinetic parameters in human from the various preclinical species

| Parameter | Scaled human range |

|---|---|

| Cl (ml min –1 kg –1 ) | 0.8–8.6 |

| V ss (l kg –1 ) | 1.5–20.5 |

| t 1/2 (h) | 2–296 |

Cl, clearance; Vss, Volume of distribution at steady state; t1/2, terminal half life

Methods

This study was conducted by GlaxoSmithKline between April 2016 and May 2016 at Hammersmith Medicines Research, London, UK. The study was performed in accordance with International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP), all applicable subject privacy requirements, and the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Local Research Ethics Committee provided approval of the study. The study is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (ID: NCT02737007). Signed informed consent was obtained from each subject before participation in the study. The human biological samples were sourced ethically and their research use was in accord with the terms of the informed consents. Additionally, all animal studies were ethically reviewed and carried out in accordance with European Directive 2010/63/EU and the GSK Policy on the Care, Welfare and Treatment of Animals.

Study population

Six healthy, male subjects aged between 18 and 55 years (inclusive), with body weight ≥50 kg and body mass index between 19.0 and 31.0 kg m–2 (inclusive) were enrolled into this study. Subjects with clinically relevant abnormalities in vital signs, electrocardiography or laboratory parameters were not allowed into the study. Subjects with exposure to significant radiation within the prior 12 months, particularly in relation to 14C, were also excluded to avoid elevation of endogenous radiocarbon in the subjects which could interfere with the sample analysis being dependent upon measurement of the [14C]‐GSK3191607 (present as a tracer in the dose) and subsequent radioactive drug‐related material.

Study design

This was an open‐label, single‐centre, single arm study comprising a screening visit, one treatment period, eight subsequent outpatient visits, and a follow‐up visit. Subjects underwent screening procedures within 30 days prior to dosing including a provision of a blood sample for assessment of endogenous 14C content.

Subjects who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were admitted to the unit on the day prior to dosing and stayed resident in the unit until after their assessments at 48 h after dosing. On the day of dosing, after an overnight fast of at least 8 h, subjects received 100 μg [14C]‐GSK3191607 (7.4 kBq) by IV infusion over 15 minutes.

Serial blood samples for parent GSK3191607 and radioactive drug‐related material (total radioactivity) PK analysis were collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes at the following times relative to the start of infusion: predose, and 0.25, 0.75, 1.5, 3, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 168, 216, 264, 312 and 336 h. Urine for total radioactivity analysis (for assessment of renal excretion of radioactive drug‐related material) was also collected during the following time periods: 0–24 and 24–48 h. Subjects returned to the unit for outpatient visits during the next 13 days for PK blood sample collection. Safety and tolerability were assessed throughout the study.

Quantification of total drug‐related radioactivity in human urine, whole blood and plasma samples

Total radioactivity measurements in urine samples (aliquot volume of 1 ml) were determined by liquid scintillation counting using an external standardization method. The lower limit of quantification (LLoQ) for total radioactivity in urine (based upon the specific activity of the radioactive GSK3191607 dosed to the subjects) was 1.3 ng equivalents of GSK3191607 ml–1 urine.

Total radioactivity measurements in whole blood (blood:water) and plasma derived from blood, were measured initially by liquid scintillation counting for screening purposes and subsequently by direct analysis by accelerator mass spectrometry following preparation to graphite (sample aliquots of 50 μl) as described in a previous publication 22. The LLoQs for total drug‐related radioactivity in blood and in plasma were 39.8 and 15.4 pg equivalents of GSK3191607 ml–1, respectively.

Bioanalysis – quantification of parent GSK3191607 in plasma

Concentrations of parent GSK3191607 in plasma (1 ml) were analysed using a validated liquid chromatography followed by accelerator mass spectrometry method. The method was validated in accordance with GSK standard operating procedures based upon published best practices 23. The LLoQ for GSK3191607 in plasma was 0.94 pg ml–1 (0.94 ng l–1).

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Plasma GSK3191607 and whole blood and plasma total radioactivity concentration–time data were analysed by noncompartmental methods with WinNonlin Version 6.3 24. Calculations were based on the actual sampling times recorded during the study. From the plasma GSK3191607 concentration–time data and total radioactivity (whole blood and plasma) data, the following PK parameters were determined: maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), area under the plasma concentration–time curve [AUC(0–t) and AUC(0–∞)], terminal phase rate constant (λz) and apparent terminal phase half‐life (t½). In addition, clearance (CL) and volume of distribution at steady‐state (Vss) were determined from the plasma GSK3191607 concentration–time data. Furthermore, the amount (Ae) and percentage of dose excreted in urine (fe) was calculated for each subject. For each of the estimated parameters, summary statistics were calculated.

Dose prediction analysis was performed utilizing the human microdose PK parameters, in addition to the in vivo efficacy preclinical parameters. The details of the dose prediction are discussed in the Supporting Information. Briefly, the microdose PK parameters were used in the simulations for dose prediction. As the microdose study was an IV study, oral absorption rate constant was assumed (KA = 0.5 h–1). A theoretical calculation of the oral bioavailability parameter (F, discussed below) of GSK3191607 provided an estimated F = 59%. The minimal parasiticidal concentration was calculated to be 0.017 μg ml–1 based on the in vivo efficacy study of GSK3191607 in the SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice model. Safety limits were calculated based on the non‐GLP studies conducted in rodents. The dose prediction aim was to predict the dosing regimen that provides blood concentrations that stay above minimal parasiticidal concentration for 3 days while maintaining safe AUC and Cmax. The evaluated dosing regimens included once daily for 1 day (i.e. single dose), twice daily for 1 day, and once daily for 3 days.

Results

The demographics of the study population are summarized in Table 2. The sample population were all men and had a mean [standard deviation (SD)] age of 35.2 (9.91) years. The mean (SD) weight for the subjects was 84.8 (8.30) kg, while the mean (SD) body mass index was 26.2 (2.74) kg m–2. Four of the six enrolled subjects were white, one was Asian, and one was Black or African American.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of clinical participants

| Demographic | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 6 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 35.2 (9.91) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| ‐ Female: | 0 |

| ‐ Male: | 6 (100) |

| Body mass index (kg m –2 ), mean (SD) | 26.2 (2.74) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 180 (6.9) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 84.8 (8.30) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino: | 0 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino: | 6 (100) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black or African American | 1 (17) |

| Asian – Central/South Asian Heritage | 1 (17) |

| White – White/Caucasian/European Heritage | 4 (67) |

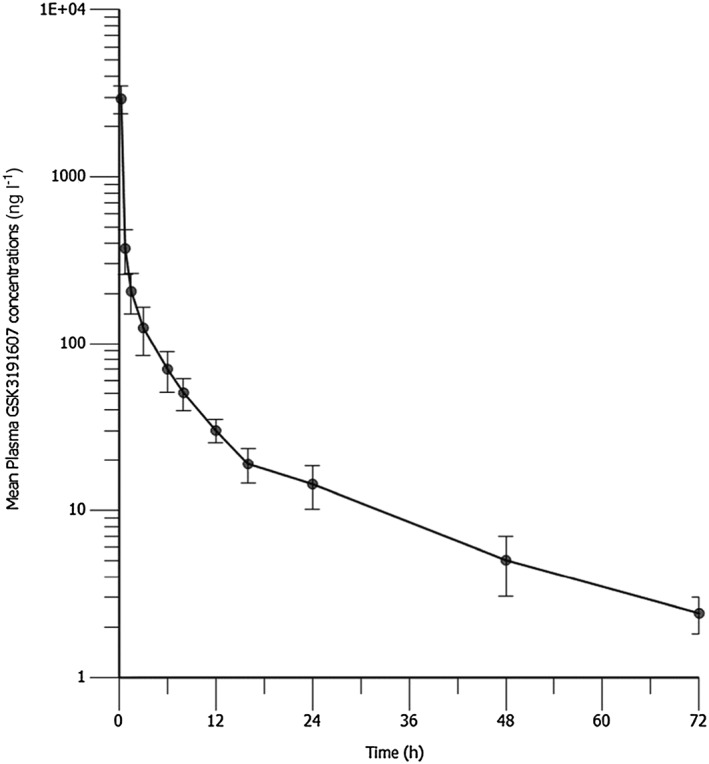

The mean (± SD) plasma GSK3191607 concentration–time profile is displayed with nominal time on a semilogarithmic scale in Figure 1. The geometric mean of GSK3191607 Cmax administered as a 100 μg single microdose by IV infusion reached 2889 ng l–1. The geometric mean AUC(0–inf) and AUC(0–t) of GSK3191607 were comparable at approximately 2500 h ng l–1. The geometric mean t½ of GSK3191607 was approximately 17 h. Total plasma clearance was 39 l h–1 and Vss was 379 l. Variability expressed as %CVb was generally low and ranged from 14 to 20% for AUC and Cmax parameters (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Mean (± standard deviation) plasma GSK3191607 concentration–time profile. Please note that concentrations expressed in ng l–1 are equivalent to pg ml–1

Table 3.

Summary of calculated human GSK3191607 parameters

| Pharmacokinetic parameter of plasma GSK3191607 | Geometric mean (%CVb) |

|---|---|

| AUC (0–inf) (h ng –1 l –1 ) | 2586 (14.4) |

| AUC (0–t) (h ng –1 l –1 ) | 2484 (15.8) |

| C max (ng l –1 ) | 2889 (20.2) |

| T max * (h) | 0.26 (0.25–0.27) |

| t½ (h) | 16.6 (39.70) |

| CL (l h –1 ) | 38.7 (14.43) |

| Vss (l) | 379 (52.2) |

AUC(0‐∞), Area under the concentration‐time curve from time zero (pre‐dose) extrapolated to infinite time; AUC(0‐t), Area under the concentration‐time curve from time zero (pre‐dose) to last time of quantifiable concentration; Cmax, Maximum observed concentration; Tmax, Time of occurrence of Cmax; t½ Terminal phase half‐life; CL, Systemic clearance of drug; Vss, Volume of distribution at steady‐state

Tmax is presented as median (minimum, maximum)

%CVb is between subject coefficient of variation and calculated as %CVb = 100*sqrt [exp(SD**2) – 1]

The PK parameters estimated for GSK3191607‐related total radioactivity in plasma and total radioactivity in blood are summarized in Table 4. The GSK3191607‐ related total radioactivity in plasma geometric mean Cmax was 1.4‐fold higher when compared to the plasma GSK3191607 Cmax. Additionally, the geometric mean of total radioactivity in plasma AUC(0–inf) and AUC(0–t) were 3.3‐ and 3.0‐fold higher than the corresponding plasma GSK3191607 parameters. The geometric mean t½ for total radioactivity in plasma was 26 h. The geometric mean Cmax of GSK3191607 total radioactivity in blood was 1.6‐fold higher in comparison to the plasma Cmax. The geometric mean of GSK3191607 total radioactivity in blood AUC(0–inf) and AUC(0–t) were both approximately 3.8‐fold higher than the corresponding plasma parameters. The mean t½ for total radioactivity in blood was approximately only 3 h. This short half‐life could be explained by the observation that the higher LLoQ for blood radioactivity probably truncated the profile and did not allow accurate determination of the terminal half‐life. Around 31% of the 100 μg GSK3191607 dose was excreted in urine within 48 h of dose administration, based on the recovery of total radioactivity in urine.

Table 4.

Summary of GSK3191607 Total Radioactivity parameters in Blood and Plasma

| Pharmacokinetic parameter | Total radioactivity in blood geometric mean (%CVb) | Total radioactivity in plasma geometric mean (%CVb) |

|---|---|---|

| AUC (0–inf) (h pgEq –1 ml –1 ) | 9918 (8.5) | 8549 (18.0) |

| AUC (0–t) (h pgEq –1 ml –1 ) | 9357 (10.1) | 7332 (18.5) |

| C max (pgEq –1 ml –1 ) | 4580 (12.9) | 4102 (19.7) |

| T max (h) | 0.26 (0.3–0.3) | 0.26 (0.3–0.3) |

| t½ (h) | 2.72 (23.893) | 25.9 (88.23) |

AUC(0‐∞), Area under the concentration‐time curve from time zero (pre‐dose) extrapolated to infinite time; AUC(0‐t), Area under the concentration‐time curve from time zero (pre‐dose) to last time of quantifiable concentration; Cmax, Maximum observed concentration; Tmax, Time of occurrence of Cmax; t½, Terminal phase half‐life; CL, Systemic clearance of drug; pgEq, picogram equivalent; Vss, Volume of distribution at steady‐state

Tmax is presented as median (minimum, maximum)

%CVb is between subject coefficient of variation and calculated as %CVb = 100*sqrt [exp(SD**2) – 1]

The results of dose prediction are provided in the Supporting Information. In summary, results of the data modelling demonstrated that the first two dosing options (one or two doses for 1 day) were not feasible when the preclinical pharmacodynamic data as well as the preclinical toxicology data and proposed safety margins for human dosing are considered. However, a once per day dosing for 3 days showed a potential for achieving the target efficacy while maintaining acceptable safety margins (especially AUC).

Administration of GSK3191607 appeared to be well tolerated in this study as no clinically significant adverse events, electrocardiography or laboratory abnormalities related to the treatment were reported or observed.

Discussion

This microdose study with GSK3191607 provided results that do not support further clinical development of the compound for a single dose cure. However, the PK profile, based on the microdose data, demonstrated a half‐life (~17 h) similar to that of KAE609, a PfATP4 inhibitor currently in clinical development (~21 h) 14, 15. The PK disposition parameters estimated from the microdose study, combined with preclinical in vitro and in vivo pharmacodynamic parameters, were all used to estimate (posthoc) the potential efficacy of various oral dosing regimens in humans. Additionally, the theoretical estimated value for the absolute bioavailability parameter estimated from the microdose study, was used in these post‐hoc simulations. Results of the dose prediction simulations demonstrated that neither single dose (single dose for 1 day) nor two doses for 1 day can achieve the efficacy target while maintaining the safety margins. However, a once per day dosing for 3 days showed a potential for achieving the target efficacy while maintaining the safety margins. Nevertheless, as a shorter dosing regimen is not feasible, GSK3191607 is not expected to offer an advantage over similar compounds in a more advanced stage of development (e.g. KAE609), especially considering that these compounds demonstrate more extended half‐lives. Therefore, a decision was made to terminate further development of GSK3191607.

Predictions of human PK based on microdose studies have been shown to provide better concordance with observed actual PK clinical data than predictions by other methods (e.g. allometry). A recent evaluation of several allometric methods was conducted on 108 compounds by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhARMA) 25.This analysis demonstrated that even with the best prediction method evaluated, the AUC in humans was only well predicted in approximately 45% of the investigated compounds. The study also demonstrated that allometric scaling methods resulted in predicting PK time–concentration curve shapes with high or medium high accuracy for only 20% of the compounds. By contrast, results from microdose studies are highly predictable of PK parameters and time–concentration curve shapes, although the prediction accuracy is dependent on the route of administration 26. With IV administration, PK parameters were scalable within a factor of two‐fold between a microdose and the therapeutic dose for all of the drugs studied (i.e. 100% success rate); in contrast, 62% of orally dosed drugs showed PK scalable within a factor of 2‐fold and 85% within a factor of 3‐fold 27. The decrease in prediction accuracy with oral dosing can be attributed to the fact that, in some cases, the assumption of dose–exposure linearity across doses (from microdose to therapeutic doses) is proven incorrect 17. PK nonlinearity can be attributed to several factors including saturation of metabolizing enzymes, drug transporters or protein binding 28. Another possible source of this nonlinearity is target‐mediated disposition; however, this is more commonly seen with biologics rather than with small molecule compounds 27. With the oral route, a major source of nonlinearity is saturation of gut wall absorption with higher doses resulting in underprediction of oral therapeutic dose in the failed prediction cases 26, 29. As nonlinearity is rarely seen with IV dosing, the current study provides high confidence for the predictions of the GSK3191607 PK parameters at higher (e.g. therapeutic) doses. GSK3191607 is being developed for oral treatment of malaria; therefore, an oral microdose study is intuitively appealing. However, GSK3191607 is a P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp) substrate. P‐gp is an intestinal efflux transporter that affects the absorption process in a saturable fashion (i.e. its limiting effect on absorption may be quantitatively important at very low doses, but is not likely to be significant at higher doses) 30. Consequently, an orally administered P‐gp substrate may exhibit nonlinearity between dose and exposure in the range from microdose to higher (therapeutic) doses. Therefore, as PK results from an oral microdose would not be extrapolated to higher oral doses with confidence, an oral microdose of GSK3191607 was not investigated in this study.

The plasma clearance of GSK3191607 was estimated (posthoc) to be moderate (~ 60% of liver plasma flow). The cumulative urinary excretion of total radioactivity of GSK3191607‐related material represented about 31% of the administered dose. This indicates that most of the compound related material is likely to be cleared hepatically via excretion into the bile (or possibly directly secreted into the gastrointestinal tract) following IV administration. The volume of distribution estimate (379 l) is much larger than total body water volume (42 l), signifying extensive tissue distribution of GSK3191607. The combination of moderate clearance and large Vss resulted in a half‐life of elimination of GSK3191607 of 17 h.

A theoretical calculation of the likely range of oral bioavailability of GSK3191607 can be performed posthoc based on the IV data alone using the following equations:

where Eh: hepatic extraction, CL: plasma clearance, Qhp: liver plasma flow = 65 l h–1 (typical value based on study subjects' weights); fe: fraction renally cleared; F: oral bioavailability; Fa: fraction absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract; Fg: fraction escaping metabolism by the gastrointestinal tract; Fh: fraction escaping metabolism by the liver.

Metabolism of GSK3191607 was not investigated in this study; therefore, as total radioactivity in urine could be attributed to the drug itself or to its metabolite(s), it provides the upper limit for fe; therefore, fe for GSK3191607 can vary between 0 and 0.31. The range obtained for Fh of GSK3191607 (Fh = 1 – Eh) is therefore 41–59%.

Fa and Fg in humans are unknown for GSK3191607. However, in nonclinical studies, the oral bioavailability of GSK3191607 has varied from 24% in rats to 83% in mice and ~100% in dogs (data on file at GSK). These results imply that the product Fa * Fg is at least 0.24 in rats, at least 0.83 in mice and close to 1.0 in dogs. Assuming Fa * Fg in humans is not outside the range seen in animals; the theoretical range for F in humans is approximately 10–59%.

The geometric mean of plasma AUC(0–t) ratio (GSK3191607 / plasma total radioactivity) was 34%, indicating that GSK3191607 accounted for ~34% of total circulating drug‐related radioactivity in plasma following IV administration. This suggests that the remaining 66% may be attributable to a metabolite, or metabolites, of GSK3191607. Plasma half‐life, following 100 μg IV dose derived from GSK3191607 was 17 h compared to 26 h derived from plasma total radioactivity, indicating that metabolite(s) probably contributed to the longer residence time and hence longer estimated half‐life of elimination for total radioactivity.

In conclusion, the information generated by this IV dose microdose study provides support for termination of the clinical development of GSK3191607 by the oral route of administration based on the short half‐life for a single dose cure. The study is an example of using microdosing to enable progression or termination (Go/No Go) decisions in drug development when the preclinical information alone does not allow such decisions to be made with confidence.

Competing Interest

At the time of conducting this study and writing the manuscript, all authors were employees and stockholders of GlaxoSmithKline. No specified compensation was given to the authors in response to the development of this article. Patent application filed in the name of GlaxoSmithKline directed to the compound GSK3191607 that is the subject of the study published in this paper. E.F. is one of the inventors of the patent application.

The authors wish to thank the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) for their supporting work on the identification of GSK3191607. This microdose study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline.

Supporting information

Data S1 The supporting document outlines the Modelling and Simulation (M&S) analysis steps involved in the dose prediction of GSK3191607

Okour, M. , Derimanov, G. , Barnett, R. , Fernandez, E. , Ferrer, S. , Gresham, S. , Hossain, M. , Gamo, F.‐J. , Koh, G. , Pereira, A. , Rolfe, K. , Wong, D. , Young, G. , Rami, H. , and Haselden, J. (2018) A human microdose study of the antimalarial drug GSK3191607 in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 482–489. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13476.

References

- 1. World Health Organization‐world malaria report, 2016. [Internet]. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/252038/1/9789241511711-eng.pdf?ua=1 (last accessed 14 December 2017).

- 2. Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phyo AP, Nkhoma S, Stepniewska K, Ashley EA, Nair S, McGready R, et al Emergence of artemisinin‐resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand: a longitudinal study. Lancet 2012; 379: 1960–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM. Evidence of artemisinin‐resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 2619–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, et al A molecular marker of artemisinin‐resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 2014; 505: 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Plouffe D, Brinker A, McNamara C, Henson K, Kato N, Kuhen K, et al In silico activity profiling reveals the mechanism of action of antimalarials discovered in a high‐throughput screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2008; 105: 9059–9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guiguemde WA, Shelat AA, Garcia‐Bustos JF, Diagana TT, Gamo FJ, Guy RK. Global phenotypic screening for antimalarials. Chem Biol 2012; 19: 116–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swinney DC, Anthony J. How were new medicines discovered? Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011; 10: 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL, et al Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature 2010; 465: 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lelièvre J, Almela MJ, Lozano S, Miguel C, Franco V, Leroy D, et al Activity of clinically relevant antimalarial drugs on Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes in an ATP bioluminescence “transmission blocking” assay. PLoS One 2012; 7: e35019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rottmann M, McNamara C, Yeung BK, Lee MC, Zou B, Russell B, et al Spiroindolones, a potent compound class for the treatment of malaria. Science 2010; 329: 1175–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spillman NJ, Allen RJ, McNamara CW, Yeung BK, Winzeler EA, Diagana TT, et al Na+ regulation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum involves the cation ATPase PfATP4 and is a target of the spiroindolone antimalarials. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 13: 227–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Pelt‐Koops J, Pett H, Graumans W, van der Vegte‐Bolmer M, van Gemert G, Rottmann M, et al The spiroindolone drug candidate NITD609 potently inhibits gametocytogenesis and blocks plasmodium falciparum transmission to anopheles mosquito vector. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 3544–3548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Phyo AP, Rueangweerayut R, Nosten F, Jittamala P, et al Spiroindolone KAE609 for falciparum and vivax malaria. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldgof GM, Durrant JD, Ottilie S, Vigil E, Allen KE, Gunawan F, et al Comparative chemical genomics reveal that the spiroindolone antimalarial KAE609 (Cipargamin) is a P‐type ATPase inhibitor. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 27806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiménez‐Díaz MB, Ebert D, Salinas Y, Pradhan A, Lehane AM, Myrand‐Lapierre M‐E, et al (+)‐SJ733, a clinical candidate for malaria that acts through ATP4 to induce rapid host‐mediated clearance of Plasmodium . Proc Natl Acad Sci 2014; 111: E5455–E5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyd R, Lalonde R. Nontraditional approaches to first‐in‐human studies to increase efficiency of drug development: will microdose studies make a significant impact? Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 81: 24–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burt T, Yoshida K, Lappin G, Vuong L, John C, Wildt SN, et al Microdosing and other phase 0 clinical trials: facilitating translation in drug development. Clin Transl Sci 2016; 9: 74–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ings RM. Microdosing: a valuable tool for accelerating drug development and the role of bioanalytical methods in meeting the challenge. Bioanalysis 2009; 1: 1293–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lewis LD. Early human studies of investigational agents: dose or microdose? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67: 277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. European Medicines Agency (EMEA) CfMPfHU . ICH guideline M3(R2) on non‐clinical safety studies for the conduct of human clinical trials and marketing authorisation for pharmaceuticals. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002941.pdf (last accessed 14 December 2017).

- 22. Young G, Corless S, Felgate C, Colthup P. Comparison of a 250 kV single‐stage accelerator mass spectrometer with a 5 MV tandem accelerator mass spectrometer–fitness for purpose in bioanalysis. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 2008; 22: 4035–4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Young GC, Seymour M, Dueker SR, Timmerman P, Arjomand A, Nozawa K. New frontiers – accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS): recommendation for best practices and harmonization from global bioanalysis consortium harmonization team. AAPS J 2014; 16: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Phoenix® WinNonlin® version 6.3 [Certara L.P. (Pharsight), St Louis, MO].

- 25. Vuppugalla R, Marathe P, He H, Jones RD, Yates JW, Jones HM, et al PhRMA CPCDC initiative on predictive models of human pharmacokinetics, part 4: prediction of plasma concentration–time profiles in human from in vivo preclinical data by using the Wajima approach. J Pharm Sci 2011; 100: 4111–4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rowland M, Benet LZ. Clinical trials and translational medicine commentaries: lead PK commentary: predicting human pharmacokinetics. J Pharm Sci 2011; 100: 4047–4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lappin G, Noveck R, Burt T. Microdosing and drug development: past, present and future. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2013; 9: 817–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lappin G, Kuhnz W, Jochemsen R, Kneer J, Chaudhary A, Oosterhuis B, et al Use of microdosing to predict pharmacokinetics at the therapeutic dose: experience with 5 drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006; 80: 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lappin G, Shishikura Y, Jochemsen R, Weaver RJ, Gesson C, Houston JB, et al Comparative pharmacokinetics between a microdose and therapeutic dose for clarithromycin, sumatriptan, propafenone, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and phenobarbital in human volunteers. Eur J Pharm Sci 2011; 43: 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lin JH, Yamazaki M. Role of P‐glycoprotein in pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003; 42: 59–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 The supporting document outlines the Modelling and Simulation (M&S) analysis steps involved in the dose prediction of GSK3191607