Abstract

Aims

Topical growth factors accelerate wound healing in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU). Due to the absence of head‐to‐head comparisons, we carried out Bayesian network meta‐analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of growth factors.

Methods

Using an appropriate search strategy, randomized controlled trials on topical growth factors compared with standard of care in patients with DFU, were included. Proportion of patients with complete healing was the primary outcome. Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) was used as the effect estimate and random effects model was used for both direct and indirect comparisons. Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation was used to obtain pooled estimates. Rankogram was generated based on surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA).

Results

A total of 26 studies with 2088 participants and 1018 events were included. The pooled estimates for recombinant epidermal growth factor (rhEGF), autologous platelet rich plasma (PRP), recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (rhPDGF) were 5.72 [3.34, 10.37], 2.65 [1.60, 4.54] and 1.97 [1.54, 2.55] respectively. SUCRA for rhEGF was 0.95. Sensitivity analyses did not reveal significant changes from the pooled estimates and rankogram. No differences were observed in the overall risk of adverse events between the growth factors. However, the growth factors were observed to lower the risk of lower limb amputation compared to standard of care.

Conclusion

To conclude, rhEGF, rhPDGF and autologous PRP significantly improved the healing rate when used as adjuvants to standard of care, of which rhEGF may perform better than other growth factors. The strength of most of the outcomes assessed was low and the findings may not be applicable for DFU with infection or osteomyelitis. The findings of this study needs to be considered with caution as the results might change with findings from head‐to‐head studies.

Keywords: autologous platelet transfusion, epidermal growth factor, platelet derived growth factor

What is Already Known about this Subject

Growth factors enhance healing of diabetic foot ulcers.

Currently there are no head‐to‐head trials directly comparing the efficacy of various growth factors.

What this Study Adds

Indirect comparisons between the growth factors conclude that recombinant human epidermal growth factor may perform better compared to other growth factors.

Introduction

Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is a full‐thickness wound involving dermis in either ankle or foot 1 with a 25% lifetime risk 2. DFU is associated with significant morbidity and the mortality ranges between 4 and 10% 3, 4. Further, the risk of amputation was between 0.06 and 3.83 per 1000 diabetics in developed countries 5 and a recurrence rate of 50% 6. Management of DFU incurs significant financial burden amounting to 45 000 USD per patient 7.

Management of DFU includes wound debridement, off‐loading the ulcer area using casts, extracellular matrix protein extracts, bio‐engineered skin substitutes, negative pressure wound therapy, hyperbaric oxygen and growth factors such as platelet derived growth factor, epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 8. These growth factors serve as the principal immediate mediators of wound healing 9. Several randomized controlled trials confirmed the efficacy of each of the above‐mentioned agents. The only meta‐analysis comparing growth factors in DFU from Cochrane concluded that the use of growth factors improved wound healing compared to standard of care alone 10. However, due to the absence of head‐to‐head clinical trials comparing all the different types of available growth factors, the authors did not attempt to evaluate the differences on determine which one was superior. Hence, we conducted the present network meta‐analysis to compare the efficacy of various growth factors used topically in the management of DFU.

Methods

Information sources and search strategy

The protocol for this review was registered with PROSPERO with the registration number CRD 42016053523 on 23 December 2016. A thorough literature search was completed on 25 December 2016 with the detailed search strategy available in Figure S1 of the supporting information. Databases searched for potential articles included Medline (through PubMed), Cochrane CENTRAL and Google Scholar. No limits were placed with respect to either language or year of publication. References from screened literature were also searched for eligible studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials comparing growth factors for DFU. Those studies that included patients with infected DFU or complicated with osteomyelitis were excluded as were the studies comparing growth factors with skin substitutes. If the studies had additional arms that received interventions other than growth factors, the data pertaining to the growth factor and placebo or standard of care arms were considered. Similarly, for the studies that had several arms receiving different doses of the same growth factor, data from the arm with the highest dose was included. Studies were to be included if they provided data on the outcome measures, number of patients achieving complete healing (primary outcome) or adverse events (secondary outcomes).

Study procedure

Two authors independently performed a literature search in the above‐mentioned databases. A pre‐tested data extraction form was created and both authors independently extracted the following data from each eligible study: trial site, year, trial methods, participants, interventions and outcomes. Disagreement between the authors was resolved through discussion. The present review and network meta‐analysis has been reported as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis (PRISMA) guidelines 11.

Statistical considerations

We assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tool under seven domains for all the eligible studies 12. A random effects model was used for both direct and indirect comparisons as this has limited assumptions and is more robust compared to a fixed effects model. The direct comparisons were performed using Revman 5.3 following heterogeneity assessment using Chi‐squared and I2 tests. We used a logistic regression model with the logit link function and binomial likelihood and chose to present the results as odds ratios (OR) for these models so as to avoid the ceiling effect that limits relative risks for outcomes with proportions around 0.8–0.95. NetMetaXL 13 and WinBUGS statistical analysis program version 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Institute of Public Health, Cambridge, UK) were used for generating results as the pooled estimates were obtained by means of the Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation method. We evaluated the sensitivity of the network to individual trials. We removed each trial one at a time and investigated the impact on the probability of which growth factor was ‘best’. We also excluded trials that measured the outcome at 20 weeks and intended to do a sensitivity analysis by excluding trials with a high risk of bias in at least one domain. Inconsistency between direct and indirect comparisons was evaluated by plotting the posterior mean deviance of individual data points for consistency and inconsistency 13. A step plot was used to compare treatment arms and a cumulative rankogram was generated based on the surface under cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) 14. Under a Bayesian approach, SUCRA estimates the probability of a treatment being the best. The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group approach was used to assess the quality of evidence 12. A probability of ≤0.05 was considered significant and no adjustments were made to multiple comparisons.

Results

Search results

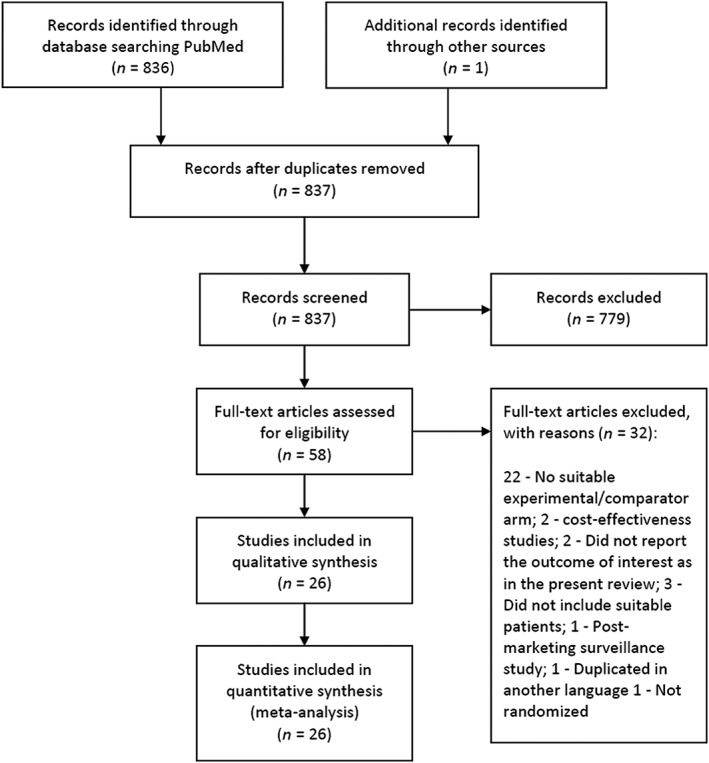

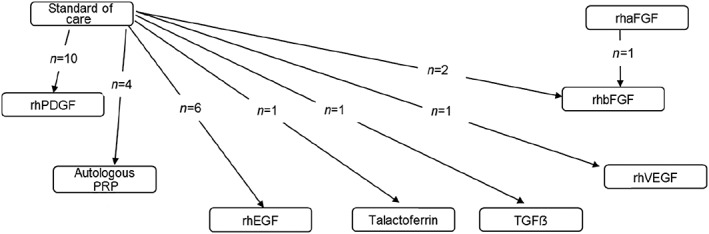

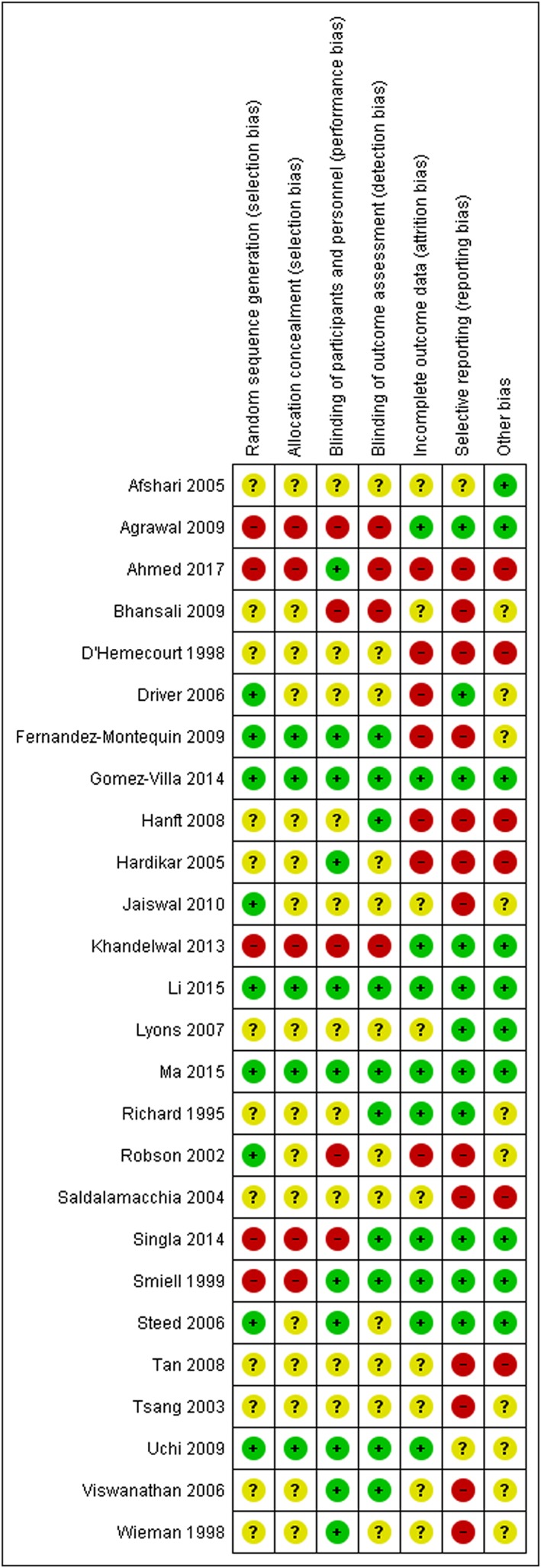

A total of 837 articles were obtained of which 26 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 were found to be eligible to be included for final analysis (Figure 1). There were a total of 2088 participants with 1018 events from all these eligible studies. Direct data with pairwise comparisons was available for eight studies. All studies except one compared the effects of adjuvant growth factors with standard of care. Ten eligible studies were obtained evaluating recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor (rhPDGF), six assessed recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhEGF), five compared autologous platelet rich plasma (PRP), three evaluated recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (two compared with standard of care and one with recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor) and one each with recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (rhVEGF) and recombinant human transforming growth factor beta (rhTGFβ). Network diagram is depicted in Figure 2. Key details of the individual studies are summarized in Table S1 of the supporting information. A summary of risk of bias of the included studies is depicted in Figure 3. We observed high risk of bias with respect to random sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding in five studies. Four studies had detection bias, seven reported incomplete outcomes and 13 had selective reporting bias. Six studies had other biases in terms of imbalances in the demographic variables, failure to report baseline characteristics of the study participants and funding.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. A total of 26 studies were found eligible to be included from 837 articles that were obtained with the search strategy

Figure 2.

Network diagram rhPDGF, recombinant human platelet derived growth factor; PRP, platelet rich plasma; rhEGF, recombinant human epidermal growth factor; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta; rhVEGF, recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor; rhbFGF, recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor; rhaFGF, recombinant human acidic fibroblast growth factor. Large majority of studies compared rhPDGF followed by rhEGF with standard of care

Figure 3.

Summary of risk of bias of the included studies. This indicates that the majority of the studies have either an unclear or a high risk in most of the elements

Pooled results

Primary outcome

Direct comparisons

All except one of the direct comparisons were performed between growth factors and standard of care. Only one study compared the efficacy of rhbFGF and rhaFGF, directly. The pooled analysis included data from 22 studies with 1785 participants. I2 was 47% and the odds ratio [95% confidence interval] was observed to be 2.23 [1.82, 2.72] favouring the use of growth factors. With regard to autologous PRP, four studies comprising a total of 227 patients without any heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) were included (Figure S2), while 10 studies (with 1129 patients; I2 = 52%) were pooled for rhPDGF (Figure S3). A total of six studies with 280 patients were included for direct comparison of rhEGF and standard of care with I2 of 42% (Figure S4). Two studies (99 patients; I2 = 46%) were included for the comparison of rhbFGF (Figure S5). The pooled estimates (Odds ratio [95% confidence interval]) for the direct comparisons revealed that rhPDGF, autologous PRP and rhEGF were associated with higher odds of complete healing against standard of care (Table 1). Only one study was obtained for each of the factors, talactoferrin, rhVEGF, rhTGFβ and rhaFGF, and so pooling of the results could not be attempted.

Table 1.

Point estimate (odds ratio) with 95% credible intervals for the mixed treatment comparisons and odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals for the direct comparisons

| Growth factor | rhEGF | Autologous PRP | rhPDGF | Talactoferrin | rhaFGF | rhVEGF | rhbFGF | Standard of care | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference intervention | Autologous PRP | Direct | – | |||||||

| MTC | 2.62 (0.75–10.36) | |||||||||

| rhPDGF | Direct | – | – | |||||||

| MTC | 3.38* (1.28–8.97) | 1.32 (0.43–3.74) | ||||||||

| Talactoferrin | Direct | – | – | – | ||||||

| MTC | 3.26 (0.31–27.72) | 0.95 (0.09–7.61) | 0.95 (0.09–7.61) | |||||||

| rhaFGF | Direct | – | – | – | – | |||||

| MTC | 3.38 (0.49–33.55) | 1.28 (0.16–14.36) | 0.97 (0.15–8.83) | 1.05 (0.08–25.89) | ||||||

| rhVEGF | Direct | – | – | – | – | – | ||||

| MTC | 3.51 (0.55–25.63) | 3.51 (0.55–25.63) | 1.05 (0.17–6.87) | 1.09 (0.08–16.40) | 1.02 (0.07–11.7) | |||||

| rhbFGF | Direct | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| MTC | 5.52* (1.30–29.33) | 5.52* (1.3–29.33) | 1.59 (0.44–6.83) | 1.73 (0.15–24.72) | 1.59 (0.35–7.11) | 1.54 (0.20–14.14) | ||||

| Standard of care | Direct | 6.81* (2.73–16.97) | 2.6* (1.56–4.36) | 2.66* (1.42–4.98) | 0.33 (0.01–8.83) | – | – | 0.84 (0.21–3.35) | ||

| MTC | 7.08* (3.24–16.88) | 2.73* (1.04–7.17) | 2.08* (1.26–3.64) | 2.22 (0.29–19.91) | 2.10 (0.28–34.75) | 2.01 (0.33–11.20) | 1.29 (0.33–4.37) | |||

| TGFβ | Direct | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| MTC | 10.69* (1.77–73.91) | 4.06 (0.57–29.93) | 3.09 (0.55–19.60) | 3.24 (0.21–55.87) | 3.22 (0.21–34.75) | 2.99 (0.26–31.28) | 1.91 (0.20–8.58) | 1.47 (0.27–8.58) | ||

Direct data are presented in the form of odds ratio (95% confidence interval) and MTC data are presented in the form of odds ratio (95% credible intervals).

P ≤ 0.05

rhEGF, autologous PRP and rhPDGF were observed with better healing response than standard of care alone both by direct and mixed treatment comparison analyses.

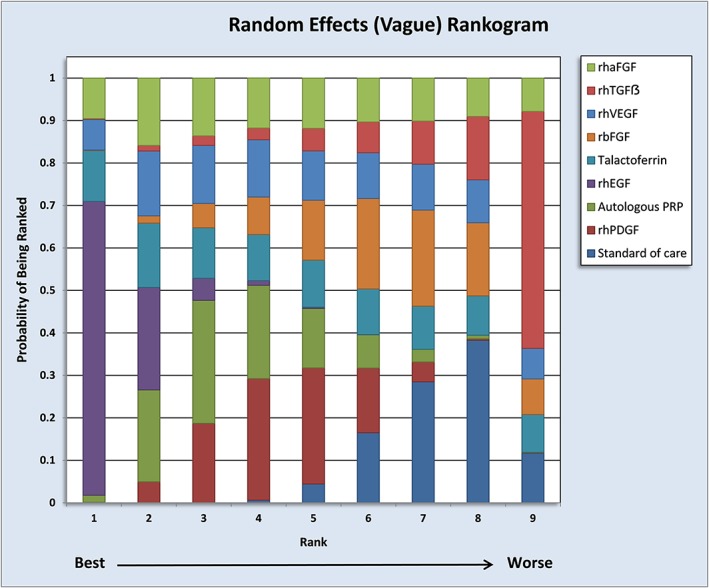

Mixed treatment comparisons

Comparisons of the efficacy between the interventions indirectly through a common comparator were performed. A statistically significant increase in the number of individuals with complete healing was observed with rhEGF, rhPDGF and autologous PRP when compared with standard of care (Table 1). Additionally, rhEGF was observed to be better than autologous PRP, rhPDGF, rhbFGF and rhTGFβ. Similarly, rhPDGF and autologous PRP significantly improved the outcome measure when compared with rhTGFβ. The consistency between the pooled estimates of indirect and available direct comparisons is illustrated in Table 1. Recombinant human epidermal growth factor was observed to perform better than other factors (Table 1). This is also substantiated by SUCRA (Figure 4). We observed a high probability for rhEGF to be the best growth factor for complete healing in DFU. No inconsistencies were observed between the direct and indirect comparisons (Figure S6).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of rankogram by SUCRA estimates. Rankogram assessment indicates a high probability for rhEGF to be the ‘best’ in the pool

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed 26 times, of which 25 involved eliminating each trial one at a time. The outcomes were analysed at 12 weeks in seven studies 16, 20, 21, 24, 26, 32, 35, at 20 weeks in six studies 28, 29, 33, 34, 37, 39, four studies 18, 23, 25, 30 measured at 8 weeks, three studies 15, 19, 36 measured at 10 weeks and one each at 4, 5, 6, 15, 16 and 24 weeks. Analysis was also performed by excluding data from studies that measured the outcome at 20 weeks as was carried out in the previous Cochrane review. At each analysis, we evaluated the factor that performed best as per SUCRA as well as the pooled effect estimates. Subsequently rhEGF was found to have the maximum probability of being the best. Regarding the pooled estimates, the results of the sensitivity analyses largely agreed with that of the main results, despite small numerical differences between both analyses. With regard to eliminating six studies that assessed the outcomes at 20 weeks, rhEGF had the highest probability of being the best intervention. The sensitivity analyses confirmed that none of the individual studies had a biased effect on both the effect estimates of the comparisons and ranking of treatment arms.

Sensitivity analyses could not be carried out for direct comparisons excluding trials with high risk of bias as there were a total of 18 studies with high risk in at least one domain. The mixed treatment comparison pooled estimates (Odds ratio [95% confidence interval]) were observed as follows: rhPDGF (1.68 [1.07, 2.64]), rhEGF (5.64 [2.07, 15.35) and autologous PRP (2.6 [1.28, 5.32]) and were comparable to the overall results.

Secondary outcomes (safety analysis)

The total number of adverse events reported in each study was pooled for each growth factor. We included data from 11 studies with 1474 participants (four in rhPDGF, three with autologous PRP, two with rhEGF and one each with rhVEGF and talactoferrin) that reported wound infection, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, skin ulceration and peripheral oedema. Sub‐group analyses were not possible for other growth factors except for rhPDGF due to limited numbers of studies. We observed six studies with 1043 participants that reported adverse events and no heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 0%) in the pooled analysis with odds ratio [95% confidence interval] of 0.90 [0.69, 1.18]. The pooled estimate for rhPDGF in the sub‐group analysis was 0.77 [0.54, 1.1]. Details of the pooled estimates for the individual adverse events are represented in Table 2 and Figures S7–S13 depict the forest plots of the same between the growth factors. The overall analysis revealed significant results only for lower limb amputation. TGFβ and autologous PRP were associated with reduced incidence of wound infection (0.23 [0.06, 0.88] and 0.35 [0.14, 0.9] respectively), TGFβ also reduces cellulitis (0.11 [0.03, 0.33]), peripheral oedema (0.02 [0, 0.01]) and rhEGF reduces local pain/burning sensation (0.36 [0.16, 0.78]). Only one study each was included for generating the above‐mentioned pooled estimates.

Table 2.

Pooled estimates for the secondary outcome measures for adjuvant growth factors

| Secondary outcomes | Number of studies; Total number of participants | Odds ratio [95% confidence intervals] |

|---|---|---|

| Wound infection | 6; 693 | 0.66 [0.41, 1.06] |

| Cellulitis | 4; 491 | 0.42 [0.11, 1.54] |

| Peripheral oedema | 3; 426 | 0.24 [0.03, 1.98] |

| Skin ulceration | 4; 443 | 1.56 [0.84, 2.4] |

| Lower limb amputation | 3; 264 | 0.41 [0.17, 0.97] * |

| Lower limb pain/burning sensation | 5; 481 | 0.75 [0.43, 1.31] |

P ≤ 0.05.

GRADE

Grading the quality of evidence was carried out separately for direct and indirect comparisons (Tables 3 and 4). The quality of evidence for most of the comparisons evaluated in the present study was observed to be low due to serious imprecision and indirectness of the estimates. For few comparisons, the quality of evidence was observed to be very low thus expressing uncertainty. Evidence for adverse events was very low due to serious limitations in consistency, indirectness and imprecision. Additionally, we could not assess the quality of evidence for adverse events to talactoferrin as there was only one study included in this review and no adverse events were observed.

Table 3.

Grading the quality of evidence for direct comparisons

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% confidence intervals) | Derived odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed risk a | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Standard of care | Growth factor | ||||

| Complete wound healing with any growth factor | 425 per 1000 | 624 per 1000 (573–664) | 2.23 [1.82, 2.72] | 1785 (22) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete wound healing with autologous PRP | 554 per 1000 | 776 per 1000 (640–862) | 2.66 [1.42, 4.98] | 227 (4) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete wound healing with rhPDGF | 361 per 1000 | 524 per 1000 (462–574) | 1.93 [1.51, 2.47] | 1129 (10) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete wound healing with rhEGF | 431 per 1000 | 795 per 1000 (693–870) | 5.11 [2.96, 8.82] | 330 (6) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete wound healing with rhbFGF | 610 per 1000 | 622 per 1000 (419–785) | 1.04 [0.46, 2.33] | 99 (2) | ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ ⊝ Very low b , c , d |

| Adverse events with any growth factor | 214 per 1000 | 199 per 1000 (159–243) | 0.90 [0.69, 1.18] | 1043 (6) | ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ ⊝ Very low b , c , e |

Assumed risk was the median control group risk across the studies

Downgraded one level for inconsistency (I2 > 40%)

Downgraded one level for imprecision of the estimates as evident by the wider confidence intervals

Downgraded one level for low sample size

Downgraded one level for less number of events

Low: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Table 4.

Grading the quality of evidence for indirect treatment comparisons

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% confidence intervals) | Derived odds ratio [95% confidence intervals] | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assumed risk a | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Growth factor 1 or standard of care | Growth factor 2 | ||||

| Complete healing with rhEGF in comparison to rhPDGF | 561 per 1000 | 824 per 1000 (598–915) | 3.38 [1.28, 8.97] | 701 (16) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete healing with rhEGF in comparison to standard of care | 421 per 1000 | 828 per 1000 (718–923) | 7.08 [3.24, 16.88] | 1167 (25) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete healing with rhEGF in comparison to rhTGFβ | 614 per 1000 | 951 per 1000 (725–991) | 10.69 [1.77, 73.91] | 218 (7) | ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ ⊝ Very low c , d |

| Complete healing with autologous PRP in comparison to standard of care | 421 per 1000 | 676 per 1000 (434–839) | 2.73 [1.04, 7.17] | 1106 (25) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

| Complete healing with rhPDGF in comparison to standard of care | 421 per 1000 | 604 per 1000 (482–726) | 2.08 [1.26, 3.64] | 1520 (25) | ⊕ ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ Low b , c |

Assumed risk was the median control group risk across the studies

Downgraded one level for serious limitations in the precision of the estimates

Downgraded one level considering the absence of direct comparisons and the indirect comparison involves one loop

Downgraded two levels for precision as evident by a wide confidence interval

Low: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low: We are very uncertain about the estimate.

Discussion

We conducted the present Bayesian network meta‐analysis to identify the effect of different growth factors in healing of DFU. A total of 26 studies involving 2088 participants with 1018 events were included. The results of the study should be carefully interpreted considering the high risk of bias observed in most of the included studies. Only three growth factors, namely rhEGF, rhPDGF and autologous PRP, were found to be better than standard of care. Additionally, rhEGF was found to be better than autologous PRP, rhPDGF, rbFGF and rhTGFβ and both autologous PRP and rhPDGF were found to be better than rhTGFβ. We also observed that rhEGF has the highest probability of being the best growth factor for the treatment of DFU and was significantly associated with a higher proportion of complete healing with standard of care, rhPDGF, autologous PRP, rhbFGF and rhTGFβ. No significant differences in the risk of adverse events were observed in the pooled analyses by indirect comparisons. However, direct comparisons revealed minor reduction in the risk of lower limb amputation.

This is the first network meta‐analysis to analyse the efficacy of various growth factors used topically for the treatment of DFU. A network meta‐analysis offers the advantage of comparison between multiple treatments not only directly but also indirectly using a common comparator 41. This is especially used in head‐to‐head comparisons with a common comparator. To discuss with a simple example, when there are three treatment arms, A, B and C, and when head‐to‐head trials have been conducted only between A and B and B and C, indirect comparisons between A and C can be made through the common comparator B. By doing so, it may be possible to identify the best among a basket of agents that can be used for treating a particular disease in the case of limited clinical evidence 42. The conclusion of a Cochrane review on a similar topic was based on the use of autologous PRP or rhPDGF with little information on rhEGF 10. The review included head‐to‐head trials that compared growth factors to either placebo or standard of care. Hence, there was no inference from the review regarding the superiority of growth factors.

Growth factors play a significant role in angiogenesis, enzyme production, cell migration and proliferation 43. EGF has been shown to stimulate epidermal and dermal repair in animal wound models 44. Deep injection of EGF into the ulcer stimulates the production of extracellular matrix proteins thereby enhancing cell proliferation and migration 45. A meta‐analysis specifically evaluating the effects of rhEGF in DFU corroborated with the findings of the present network meta‐analysis 46.

Topical use of growth factors was observed to reduce the incidence of lower limb amputation. Studies suggest good tolerability profile with frequent adverse events that include burning sensation, tremor, chills and local pain 47. This is also confirmed by a prospective, active post‐marketing surveillance study in 41 hospitals and 19 primary care polyclinics wherein 1835 DFU patients on rhEGF were evaluated 48. However, the safety results from this review should be considered as preliminary evidence because of limited data precluding firm conclusions. Further, the quality of evidence for adverse event outcomes for growth factors in the present review was graded very low due to serious limitations in terms of inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision.

Multi‐disciplinary approaches are essential for the management of any wound, particularly DFU. Wound debridement, removal of necrotic tissue and infection control are the prime requisites of wound management and addition of growth factors facilitates the therapeutic effect. Generation of cost‐effectiveness data is required urgently to prioritize the use of growth factors in the management of DFU. Also, head‐to‐head comparison using various growth factors in the management of DFU may also shed light on the difference in clinically significant effect size between the agents 49.

The strength of the present review is that this is the first evidence comparing the efficacies and safety of various growth factors, albeit indirectly. From a clinical standpoint, it might take years to generate real‐time evidence based on clinical trials. Secondly, we also found that both rhPDGF and autologous PRP tend to be more efficacious than standard of care when trials that assessed the outcome at 20 weeks were included. Future studies should explore the temporal relationship of the wound‐healing effects of these growth factors. However, the results should be interpreted considering the variations in the duration of ulcer, standard of care, administration of antimicrobial agents and anti‐diabetic drugs that were administered to the study participants. Also, this review excluded patients with infected DFU or DFU complicated with osteomyelitis. Eighteen studies in the present review had high risk of bias in one or more elements. Authors of future studies should take care in eliminating or reducing systematic errors in all domains to generate high quality evidence. Another limitation of the study is the low quality of evidence for most of the comparisons and that we did not search EMBASE due to access constraints.

To conclude, adjuvant topical rhEGF, rhPDGF and autologous PRP were found to be more beneficial than standard of care and rhEGF might be the best growth factor in the pool. However, the results should be interpreted with extreme caution as the results might change with the publication of head‐to‐head studies in future.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

We thank PROSPERO for registering the review protocol and Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health for utilizing NetMetaXL in generating the pooled results. We are also grateful to MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge for using WINBUGS software and Cochrane Group for utilizing the risk of bias tool and RevMan software in generating forest plots.

Contributors

K.S. conceived the idea of this review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; K.S. and G.S. were involved in designing the protocol, data collection and data analysis, and reviewed and approved the final draft.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Search strategy

Table S1 Key characteristics of the included studies

Figure S2 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for autologous PRP for wound healing

Figure S3 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for rhPDGF with standard of care for wound healing

Figure S4 Forest plot of the direct comparisons between rhEGF with standard of care for wound healing

Figure S5 Forest plot of the direct comparison of rhbFGF with standard of care for wound healing

Figure S6 Consistency plot between the direct and indirect estimates

Figure S7 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for adverse events

Figure S8 Forest plot of the direct comparisons for wound infection

Figure S9 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for incidence of cellulitis

Figure S10 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for peripheral oedema

Figure S11 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for skin ulceration

Figure S12 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for the risk of lower limb amputation

Figure S13 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for lower limb pain or burning sensation

Sridharan, K. , and Sivaramakrishnan, G. (2018) Growth factors for diabetic foot ulcers: mixed treatment comparison analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 434–444. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13470.

References

- 1. Lavery LA, Peters EJG, Williams JR, Murdoch DP, Hudson A, Lavery DC, et al Re‐evaluating the way we classify the diabetic foot. Restructuring the diabetic foot risk classification system of the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim JZ, Ng NS, Thomas C. Prevention and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J R Soc Med 2017; 110: 104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lauterbach S, Kostev K, Kohlmann T. Prevalence of diabetic foot syndrome and its risk factors in the UK. J Wound Care 2010; 19: 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Med 2017; 49: 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alexiadou K, Doupis J. Management of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Ther 2012; 3: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boulton AJ, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson‐Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet 2005; 366: 1719–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stockl K, Vanderplas A, Tafesse E, Chang E. Costs of lower‐extremity ulcers among patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 2129–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jeffcoate WJ. The incidence of amputation in diabetes. Acta Chir Belg 2005; 105: 140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bennett SP, Griffiths GD, Schor AM, Leese GP, Schor SL. Growth factors in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martí‐Carvajal AJ, Gluud C, Nicola S, Simancas‐Racines D, Reveiz L, Oliva P, et al Growth factors for treating diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; Issue 10. Art. No.: CD008548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1 edn. Available at www.cochrane.org/handbook (last accessed 9 February 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown S, Hutton B, Clifford T, Coyle D, Grima D, Wells G, et al A Microsoft‐Excel‐based tool for running and critically appraising network meta‐analyses: an overview and application of NetMetaXL. Syst Rev 2014; 3: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rucker G, Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta‐analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015; 15: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khandelwal S, Chaudhary P, Poddar DD, Saxena N, Singh RA, Biswal UC. Comparative study of different treatment options of grade III and IV diabetic foot ulcers to reduce the incidence of amputations. Clin Pract 2013; 3: e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahmed M, Reffat SA, Hassan A, Eskander F. Platelet‐rich plasma for the treatment of clean diabetic foot ulcers. Ann Vasc Surg 2017; 38: 206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Driver VR, Handft J, Fylling CP, Beriou JM, the Autogel Diabetic Foot Ulcer study group . A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of autologous platelet‐rich plasma gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 2006; 52: 68–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gomez‐Villa R, Aguilar‐Rebolledo F, Lozano‐Platonoff A, Teran‐Soto JM, Fabian‐Victoriano MR, Kresch‐Tronik NS, et al Efficacy of intralesional recombinant human epidermal growth factor in diabetic foot ulcers in Mexican patients: a randomized double‐blinded controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen 2014; 22: 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jaiswal SS, Gambhir RPS, Agrawal A, Harish S. Efficacy of topical recombinant human platelet derived growth factor on wound healing in patients with chronic diabetic lower limb ulcers. Indian J Surg 2010; 72: 27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li L, Chen D, Wang C, Yuan N, Wang Y, He L, et al Autologous platelet‐rich gel for treatment of diabetic chronic refractory cutaneous ulcers: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Wound Repair Regen 2015; 23: 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyons TE, Miller MS, Serena T, Sheehan P, Lavery L, Kirsner RS, et al Talactoferrin alfa, a recombinant human lactoferrin promotes healing of diabetic neuropathic ulcers: a phase 1/2 clinical study. Am J Surg 2007; 193: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma C, Hernandez MA, Kirkpatrick VE, Liang L‐J, Nouvong AL, Gordon II. Topical platelet‐derived growth factor vs placebo therapy of diabetic foot ulcers offloaded with windowed casts: a randomized, controlled trial. Wounds 2015; 27: 83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernández‐Montequín JI, Valenzuela‐Silva CM, Díaz OG, Savigne W, Sancho‐Soutelo N, Rivero‐Fernández F, et al Intra‐lesional injections of recombinant human epidermal growth factor promote granulation and healing in advanced diabetic foot ulcers: multicenter, randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study. Int Wound J 2009; 6: 432–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Richard JL, Parer‐Richard C, Daures JP, Clouet S, Vannereau D, Bringer J, et al Effect of topical basic fibroblast growth factor on the healing of chronic diabetic neuropathic ulcer of the foot. Diabetes Care 1995; 18: 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singla S, Garg R, Kumar A, Gill C. Efficacy of topical application of beta urogastrone (recombinant human epidermal growth factor) in Wagner's grade 1 and 2 diabetic foot ulcers: comparative analysis of 50 patients. J Nat Sci Biol Med 2014; 5: 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsang MW, Wong WK, Hung CS, Lai KM, Tang W, Cheung EY, et al Human epidermal growth factor enhances healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1856–1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Viswanathan V, Pendsey S, Sekar N, Murthy GSR. A phase III study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of recombinant human epidermal growth factor (REGEND™ 150) in healing diabetic wounds. Wounds 2006; 18: 186–196. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smiell JM, Wieman J, Steed DL, Perry BH, Sampson AR, Schwab BH. Efficacy and safety of becaplermin (recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor‐BB) in patients with non healing, lower extremity diabetic ulcers: a combined analysis of four randomized studies. Wound Repair Regen 1999; 7: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wieman TJ, Smiell JM, Su Y. Efficacy and safety of a topical gel formulation of recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor‐BB (Becaplermin) in patients with chronic neuropathic diabetic ulcers. Diabetes Care 1998; 21: 822–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uchi H, Igarashi A, Urabe K, Koga T, Nakayama J, Kawamori R, et al Clinical efficacy of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) for diabetic ulcer. Eur J Dermatol 2009; 19: 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Afshari M, Larigani B, Fadayee M, Darvishzadeh F, Ghahary A, Pajouhi M, et al Efficacy of topical epidermal growth factor in healing diabetic foot ulcers. Therapy 2005; 2: 759–765. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Agrawal RP, Jhajharia A, Mohta N, Dogra R, Chaudhari V, Nayak KC. Use of a platelet‐derived growth factor gel in chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Diabet Foot J 2009; 12: 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhansali A, Venkatesh S, Dutta P, Dhillon MS, Das S, Agrawal A. Which is the better option: recombinant human PDGF‐BB 0.01% gel or standard wound care, in diabetic neuropathic large plantar ulcers off‐loaded by a customized contact cast? Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009; 83: e13–e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. D'Hemecourt PA, Smiell J, Karim MR. Sodium carboxymethylcellulose aqueous‐based gel vs. becaplermin gel in patients with nonhealing lower extremity diabetic ulcers. Wounds 1998; 10: 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hanft JR, Pollak RK, Barbul A, van Gils C. Phase 1 trial on the safety of topical rhVEGF on chronic neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. J Wound Care 2008; 17: 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hardikar JV, Reddy C, Bung DD, Varma N, Shilotri PP, Prasad ED, et al Efficacy of recombinant human platelet derived growth factor (rhPDGF) based gel in diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized, multicenter, double blind, placebo controlled study in India. Wounds 2005; 17: 141. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robson MC, Steed DL, McPherson JM, Pratt BM. Effects of transforming growth factor +2 on wound healing in diabetic foot ulcers: a randomized controlled safety and dose‐ranging trial. J Appl Res 2002; 2: 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saldalamacchia G, Lapice E, Cuomo V, De Feo E, D'Agostino E, Rivellesse AA, et al A controlled study of the use of autologous platelet gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2004; 14: 395–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steed DL. Clinical evaluation of recombinant human platelet‐derived growth factor for the treatment of lower extremity ulcers. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117: 143S–150S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tan Y, Xiao J, Huang Z, Xiao Y, Lin S, Jin L, et al Comparison of the therapeutic effects of recombinant human acidic and basic fibroblast growth factors in wound healing in diabetic patients. J Health Sci 2008; 54: 432–440. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li T, Puhan MA, Vedula SS, Singh S, Dickersin K, Ad Hoc Network Meta‐analyis Methods Meeting Working Group . Network meta‐analysis: highly attractive but more methodological research is needed. BMC Med 2011; 9: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Greco T, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Saleh O, Pasin L, Cabrini L, Zangrillo A, et al The attractiveness of network meta‐analysis: a comprehensive systematic and narrative review. Heart Lung Vessel 2015; 7: 133–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fitton AR, Drew P, Dickson WA. The use of a bilaminate artificial skin substitute (Integra) in acute resurfacing of burns: an early experience. Br J Plast Surg 2001; 54: 208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mustoe TA, Pierce GF, Morishima C, Deuel TF. Growth factor induced acceleration of tissue repair through direct and inductive activities. J Clin Invest 1991; 87: 694–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berlanga J, Fernández JI, López E, López PA, del Rio A, Valenzuela C, et al Heberprot‐P: a novel product for treating advanced diabetic foot ulcer. MEDICC Rev 2013; 15: 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang S, Geng Z, Ma K, Sun X, Fu X. Efficacy of topical recombinant human epidermal growth factor for treatment of diabetic foot ulcer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2016; 15: 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dumantepe M, Fazliogullari O, Seren M, Uyar I, Basar F. Efficacy of intralesional recombinant human epidermal growth factor in chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Growth Factors 2015; 33: 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Year‐Alos I, Alonso‐Carbonell L, Valenzuela‐Silva CM, Tuero‐Iglesias AD, Moreira‐Martínez M, Marrero‐Rodríguez I, et al Active post‐marketing surveillance of the intralesional administration of human recombinant epidermal growth factor in diabetic foot ulcers. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2013; 14: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kavitha KV, Tiwari S, Purandare VB, Khedkar S, Bhosale SS, Unnikrishnan AG. Choice of wound care in diabetic foot ulcer: a practical approach. World J Diabetes 2014; 5: 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Search strategy

Table S1 Key characteristics of the included studies

Figure S2 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for autologous PRP for wound healing

Figure S3 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for rhPDGF with standard of care for wound healing

Figure S4 Forest plot of the direct comparisons between rhEGF with standard of care for wound healing

Figure S5 Forest plot of the direct comparison of rhbFGF with standard of care for wound healing

Figure S6 Consistency plot between the direct and indirect estimates

Figure S7 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for adverse events

Figure S8 Forest plot of the direct comparisons for wound infection

Figure S9 Forest plot of the direct comparison analysis for incidence of cellulitis

Figure S10 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for peripheral oedema

Figure S11 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for skin ulceration

Figure S12 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for the risk of lower limb amputation

Figure S13 Forest plot of direct comparison analysis for lower limb pain or burning sensation