Abstract

Adherence is pivotal but challenging in ulcerative colitis (UC) treatment. Many methods to assess adherence are subjective or have limitations. (Nac‐)5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) urinalysis by high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) seems feasible and reproducible in healthy volunteers. We performed a prospective study in adult quiescent UC patients to evaluate the feasibility of spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis by HPLC to assess adherence in daily inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care. Twenty‐nine patients (51.7% male, mean age 52 ± 11 years) were included (median FU 9 months) and weekly spot urine samples were collected. We found large variation in spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion that was unrelated to brand, dosing schedule or dosage of 5‐ASA. In conclusion, spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis is not applicable to assess 5‐ASA adherence in daily IBD care.

Keywords: adherence, compliance, HPLC, inflammatory bowel disease, MMX‐mesalazine

What is Already Known about this Subject

It is challenging to objectively measure adherence.

HPLC can be used to perform (Nac‐)‐5ASA urinalysis.

24–96 h urinary (Nac‐)5ASA excretion is comparable for most oral 5‐ASA formulations.

What this Study Adds

Results from (Nac‐)5ASA excretion measured in 24–96 h urine cannot be extrapolated to results measured in spot urine.

There is a wide variation in urinary (Nac‐)5‐ASA excretion in UC patients regardless of disease activity, 5‐ASA brand or dosing schedules.

Spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis is not suitable for assessing (partial) 5‐ASA adherence in daily IBD practice.

Introduction

Adherence to drug therapy is indispensible for successful inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treatment, because non‐adherence bears a higher risk of relapse 1, 2, 3, 4 and higher costs 5, 6. The reported prevalence of non‐adherence to drugs is around 40–91% in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients on 5‐ASA 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Self‐report measures for adherence have well‐known limitations 12 and overestimate actual use 13, with electronic monitoring systems being more reliable but costly 14, 15. Another ‘more objective’ method to measure adherence is to assess serum or urinary drug levels. Potential pitfalls of spot serum drug analysis are poor correlation with daily steady‐state concentrations 16, and ‘white coat compliance’ 13, 16, 17. Urinalysis with more stable drug metabolites is therefore preferable. High‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) can be used to measure urinary 5‐ASA and N‐acetyl‐5‐ASA (Nac‐5‐ASA) metabolites 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24. In 2015, we performed urinalysis in healthy volunteers using MMX‐mesalazine (Mezavant®). HPLC spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis proved to be fast, reproducible and sensitive 25. The question arose whether these results could be extrapolated to UC patients on 5‐ASA, in view of the presence of diarrhoea, co‐morbidity and use of co‐medication in UC patients. To this end, we conducted a study in UC patients to assess feasibility, reliability and usefulness of HPLC 5‐ASA urinalysis for 5‐ASA adherence in daily IBD practice.

Methods

We conducted a randomized prospective study (trial number NTR4648) in UC patients using 5‐ASA, modelled after a pilot study in healthy volunteers 25. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Informed consent was obtained. We included adult UC patients (Montreal E1–E3) 26, who were in clinical remission (Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) <5) 27 and treated with 5‐ASA monotherapy or combination with topical therapy. Patients were randomized at baseline to either 2400 mg MMX‐mesalazine (Mezavant®) once‐daily (OD) or 1200 mg twice daily (BID). At randomization and during follow‐up, we collected clinical characteristics, blood and faecal samples, and weekly spot urinary (Nac‐)5‐ASA samples. Urine samples were frozen at −20°C by the UC patients, and stored at −20°C in the laboratory until further analysis with HPLC as described in detail previously 25. To mimic daily practice, patients visited the outpatient clinic twice a year, urine and faeces samples were collected at home, and quarterly interviews were conducted by telephone or digitally.

Results

We included 29 patients with a median follow‐up of 9 months. Missing values were not imputed. Demographic data, SCCAI, Morisky adherence scale (MMAS‐8) 28, 29 and laboratory results are described in Table 1. In line with the SCCAI, laboratory results did not change during 6 months of follow‐up, but faecal calprotectin fluctuated. Self‐reported adherence was high according to MMAS‐8.

Table 1.

Demographics and laboratory results

| Demographics | n = 29 a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n, %) | 15 (51.72%) | ||

| Age (years) | 52 ± 11 (20–67) | ||

| Duration disease (months) | 168 ± 114 (9–468) | ||

| Duration FU (months) | 9.7 ± 4.1 (1.6–18) | ||

|

Laboratory results |

Baseline

a

n = 29 |

3 months

n = 17 |

6 months

a

n = 19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faecal calprotectin (μg g −1 ) (median) | 117 (5–1800) | 46 (5–483) | 74 (5–1578) |

| Haemoglobin (mmol l −1 ) | 9.1 ± 0.9 (7.1–11) | ‐ | 9.2 ± 0.8 (8–10.4) |

| CRP (mg l −1 ) (median) | 3 (3–20) | ‐ | 3 (2–26) |

| Albumin (g l −1 ) | 39.2 ± 2.8 (33–44) | ‐ | 38.2 ± 2.2 (34–42) |

| Creatinine (mg mmol l −1 ) | 75.3 ± 14.6 (53–113) | ‐ | 76.9 ± 14.0 (53–107) |

| n = 29 | n = 22 | n = 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCCAI (median) | 2 (0–5) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–9) |

| MMAS‐8 (median) | 10 (1–11) | 10 (4–11) | 11 (5–11) |

Data mentioned as mean ± SD (range), unless specified otherwise

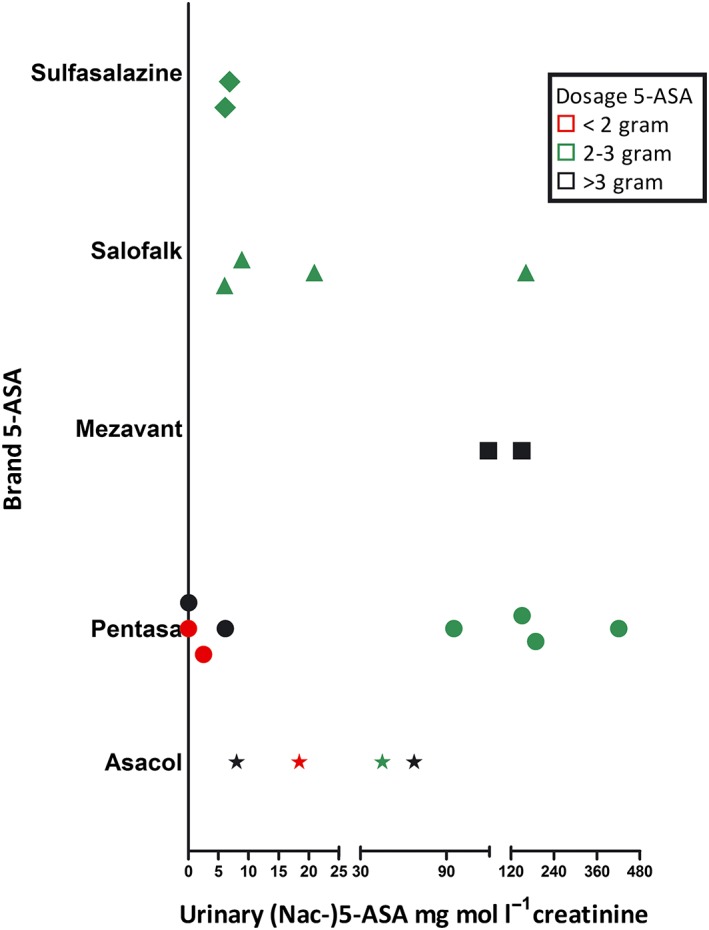

At screening, patients used different brands and dosages of 5‐ASA medication. Twenty patients provided a spot urine sample at screening to measure (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion, which showed a large variation independent of dosage or brand. Results are depicted in Figure 1, where each point reflects an individual patient.

Figure 1.

Individual spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion (5‐ASA/mg mmol l−1 creatinine) using different brands and dosages 5‐ASA at screening

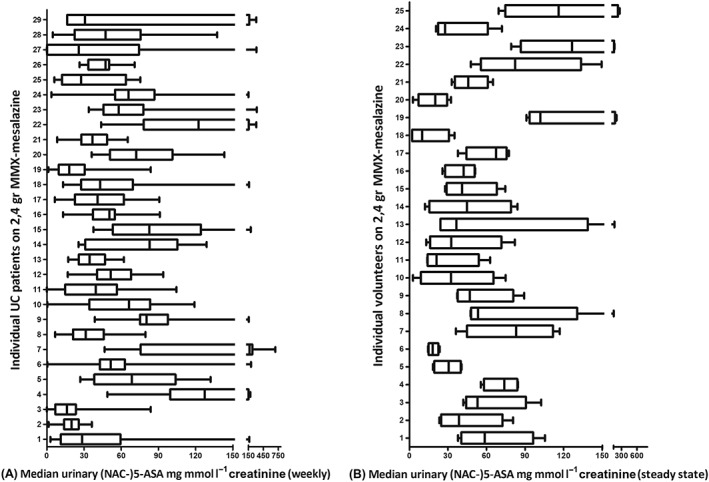

UC patients on 2400 mg MMX‐mesalazine collected and froze urine samples every week to perform (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis with HPLC. Results of all analyses were comparable for both dosing frequencies. The results varied greatly, both between and within individuals (Figure 2A). Results are displayed as median, inter‐quartile range, minimum and maximum.

Figure 2.

(A) Individual (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion (5‐ASA/mg mmol l−1 creatinine) in 29 UC patients using 2400 mg MMX‐mesalazine. (B) Individual steady state results of (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion (5‐ASA/mg mmol l−1 creatinine) in 25 healthy volunteers using 2400 mg MMX‐mesalazine

As reference material, a visual comparison of steady state results of (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion in volunteers using 2400 mg MMX‐mesalazine (median of both dosing frequencies: OD2400 mg and BID 1200 mg) is displayed in Figure 2(B) 25.

Discussion

We found large variation in spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion at any time point, both between and within individual UC patients. The variation was independent of the use of different brands, dosages or dosage schemes of 5‐ASA. Although 24–96 h urinary 5ASA excretion was found comparable for most oral 5‐ASA formulations, this cannot be extrapolated to spot urinary excretion values because other factors such as disease activity, dosing schedules, and timing of urinalysis may impact results 30, 31. It is challenging to establish cut‐off values for (partial) adherence based on spot urinalysis when using different formulations of 5‐ASA. Naturally, undetectable drug levels matching complete non‐adherence speak for themselves and may be used in daily practice. However, the question arises whether this relatively laborious method would be cost‐effective in the entire IBD population in daily practice as partial (non)adherence is the main issue at stake, whereas complete non‐adherence is ‘only’ seen in about 12% of UC patients using 5ASA 11, 24.

To overcome the issues of different dosing and brands, we switched all UC patients to one 5‐ASA‐formulation and dosage. Still, we found a wide variability in median (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion both between different patients, but also within individuals (Figure 2A).

We found larger variability and ranges in (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinary excretion in UC patients compared to volunteers (Figure 2). We did not use statistics because of small sample sizes, and different coverage time in both groups.

Direct observation of medication intake, and a strict timetable of urine collection in the healthy volunteers might have played a role in this observation. However, the contribution of UC disease activity appears to be a relevant factor. UC is a relapsing‐remitting disease 32 and, in concordance with this, our patients had fluctuating disease activity as reflected by varying faecal calprotectin levels. We noticed that clinical activity score (SCCAI) remained stable during 6 months of follow‐up, which accords with literature date 33. Inverse correlation with UC activity and mucosal colonic concentrations of 5‐ASA have been described, probably reflecting lower absorption ability due to active mucosal activity and ulcers 34, 35. Differences in colonic transit time or intestinal pH according to UC activity and extent may also lead to altered absorption of 5ASA 30. IBD patients use more co‐medication with possible interactions 36 and have additional co‐morbidities 37, 38, 39 that might affect pharmacokinetics. All patients reported high adherence levels according to MMAS, but this might reflect overestimation 13, 40. We did not compare the (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis with methods superior to MMAS such as pharmacy data, tablet counts or MEMS 40. While MEMS is expensive, pharmacy data and pill count would have been good alternatives during the study period. However, we wanted to find an easy and feasible adherence tool that can be implemented in ‘real‐world’ IBD practice. Our trial mirrored real‐world practice with a similar pattern of hospital visits (routinely twice a year) and chronic prescriptions for these quiescent UC patients to minimize the ‘positive study effect’ on adherence 41.

In conclusion, spot (Nac‐)5‐ASA urinalysis is not suitable for assessing 5‐ASA adherence in daily IBD practice due to large inter‐ and intra‐patient variability, not even when using one single brand and dosage. In view of our findings, it is not possible to set cut‐off values for (partial) adherence in UC patients. Alternative strategies are needed to reliably monitor medication adherence.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

T.E.H.R. received an unrestricted grant to perform studies in IBD patients from Tramedico and Shire.

Contributors

T.E.H.R. was responsible for the conception or design of the work, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting the article. R.t.M. was responsible for the data collection, and data analysis and interpretation. W.P. was responsible for the data analysis and interpretation. F.H. was responsible for the conception or design of the work. J.P.H.D. was responsible for the conception or design of the work. All authors critically revised the article and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Römkens, T. E. H. , te Morsche, R. , Peters, W. , Burger, D. M. , Hoentjen, F. , and Drenth, J. P. H. (2018) Urinalysis of MMX‐mesalazine as a tool to monitor 5‐ASA adherence in daily IBD practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 477–481. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13462.

References

- 1. Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med 2003; 114: 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kane S, Katz S, Jamal MM, Safdi M, Dolin B, Solomon D, et al Strategies in maintenance for patients receiving long‐term therapy (SIMPLE): a study of MMX mesalamine for the long‐term maintenance of quiescent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kawakami A, Tanaka M, Nishigaki M, Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Hibi T, et al Relationship between non‐adherence to aminosalicylate medication and the risk of clinical relapse among Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission: a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol 2013; 48: 1006–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khan N, Abbas AM, Bazzano LA, Koleva YN, Krousel‐Wood M. Long‐term oral mesalazine adherence and the risk of disease flare in ulcerative colitis: nationwide 10‐year retrospective cohort from the veterans affairs healthcare system. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36: 755–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mitra D, Hodgkins P, Yen L, Davis KL, Cohen RD. Association between oral 5‐ASA adherence and health care utilization and costs among patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2012; 12: 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bassi A, Dodd S, Williamson P, Bodger K. Cost of illness of inflammatory bowel disease in the UK: a single centre retrospective study. Gut 2004; 53: 1471–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ford AC, Khan KJ, Sandborn WJ, Kane SV, Moayyedi P. Once‐daily dosing vs. conventional dosing schedule of mesalamine and relapse of quiescent ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 2070–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baars JE, Zelinkova Z, Mensink PB, Markus T, Looman CW, Kuipers EJ, et al High therapy adherence but substantial limitations to daily activities amongst members of the Dutch inflammatory bowel disease patients' organization: a patient empowerment study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 864–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, Hanauer SB. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 2929–2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Barkun A, Bitton A, Wild GE, Cohen A, et al Patient nonadherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 1535–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shale MJ, Riley SA. Studies of compliance with delayed‐release mesalazine therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 18: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mihalko SL, Brenes GA, Farmer DF, Katula JA, Balkrishnan R, Bowen DJ. Challenges and innovations in enhancing adherence. Control Clin Trials 2004; 25: 447–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Urquhart J. The electronic medication event monitor. Lessons for pharmacotherapy. Clin Pharmacokinet 1997; 32: 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greenlaw SM, Yentzer BA, O'Neill JL, Balkrishnan R, Feldman SR. Assessing adherence to dermatology treatments: a review of self‐report and electronic measures. Skin Res Technol 2010; 16: 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cramer JA, Scheyer RD, Mattson RH. Compliance declines between clinic visits. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150: 1509–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feldman SR, Camacho FT, Krejci‐Manwaring J, Carroll CL, Balkrishnan R. Adherence to topical therapy increases around the time of office visits. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57: 81–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hussain FN, Ajjan RA, Moustafa M, Anderson JC, Riley SA. Simple method for the determination of 5‐aminosalicylic and N‐acetyl‐5‐aminosalicylic acid in rectal tissue biopsies. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 1998; 716: 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fischer C, Maier K, Klotz U. Simplified high‐performance liquid chromatographic method for 5‐aminosalicylic acid in plasma and urine. J Chromatogr 1981; 225: 498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gifford AE, Berg AH, Lahiff C, Cheifetz AS, Horowitz G, Moss AC. A random urine test can identify patients at risk of Mesalamine non‐adherence: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tjornelund J, Hansen SH. High‐performance liquid chromatographic assay of 5‐aminosalicylic acid (5‐ASA) and its metabolites N‐beta‐D‐glucopyranosyl‐5‐ASA, N‐acetyl‐5‐ASA, N‐formyl‐5‐ASA and N‐butyryl‐5‐ASA in biological fluids. J Chromatogr 1991; 570: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shaw IS, Jobson BA, Silverman D, Ford J, Hearing SD, Ball D, et al Is your patient taking the medicine? A simple assay to measure compliance with 5‐aminosalicylic acid‐containing compounds. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 2053–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moshkovska T, Stone MA, Smith RM, Bankart J, Baker R, Mayberry JF. Impact of a tailored patient preference intervention in adherence to 5‐aminosalicylic acid medication in ulcerative colitis: results from an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17: 1874–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moshkovska T, Stone MA, Clatworthy J, Smith RM, Bankart J, Baker R, et al An investigation of medication adherence to 5‐aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, using self‐report and urinary drug excretion measurements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30: 1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Römkens TEH, Salomon J, Peters WHM, Burger DM, Hoentjen F, Drenth JPH. Urinary excretion levels of MMX‐Mesalazine as a tool to assess non‐adherence. Pharm Anal Acta 2015; 6: 443. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006; 55: 749–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut 1998; 43: 29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trindade AJ, Ehrlich A, Kornbluth A, Ullman TA. Are your patients taking their medicine? Validation of a new adherence scale in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and comparison with physician perception of adherence. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17: 599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel‐Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens 2008; 10: 348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30. Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Systematic review: the pharmacokinetic profiles of oral mesalazine formulations and mesalazine pro‐drugs used in the management of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 17: 29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hussain FN, Ajjan RA, Kapur K, Moustafa M, Riley SA. Once versus divided daily dosing with delayed‐release mesalazine: a study of tissue drug concentrations and standard pharmacokinetic parameters. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15: 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017; 389: 1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baars JE, Nuij VJ, Oldenburg B, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Majority of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission have mucosal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1634–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naganuma M, Iwao Y, Ogata H, Inoue N, Funakoshi S, Yamamoto S, et al Measurement of colonic mucosal concentrations of 5‐aminosalicylic acid is useful for estimating its therapeutic efficacy in distal ulcerative colitis: comparison of orally administered mesalamine and sulfasalazine. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2001; 7: 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frieri G, Giacomelli R, Pimpo M, Palumbo G, Passacantando A, Pantaleoni G, et al Mucosal 5‐aminosalicylic acid concentration inversely correlates with severity of colonic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2000; 47: 410–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Buckley JP, Kappelman MD, Allen JK, Van Meter SA, Cook SF. The burden of comedication among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013; 19: 2725–2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mikocka‐Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016; 22: 752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Román ALS, Muñoz F. Comorbidity in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 2723–2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin TY, Chen YG, Lin CL, Huang WS, Kao CH. Inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk of peripheral arterial disease: a nationwide cohort study. Medicine 2015; 94: e2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. El Alili M, Vrijens B, Demonceau J, Evers SM, Hiligsmann M. A scoping review of studies comparing the medication event monitoring system (MEMS) with alternative methods for measuring medication adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 82: 268–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Onzenoort HA, Menger FE, Neef C, Verberk WJ, Kroon AA, de Leeuw PW, et al Participation in a clinical trial enhances adherence and persistence to treatment: a retrospective cohort study. Hypertension 2011; 58: 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]