Abstract

Genetic modifiers alter disease progression in both preclinical models and subjects with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Using multiparametric magnetic resonance (MR) techniques, we compared the skeletal and cardiac muscles of two different dystrophic mouse models of DMD, which are on different genetic backgrounds, the C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx (B10-mdx) and D2.B10-Dmdmdx (D2-mdx). The proton transverse relaxation constant (T2) using both MR imaging and spectroscopy revealed significant age-related differences in dystrophic skeletal and cardiac muscles as compared with their age-matched controls. D2-mdx muscles demonstrated an earlier and accelerated decrease in muscle T2 compared with age-matched B10-mdx muscles. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging indicated differences in the underlying muscle structure between the mouse strains. The fractional anisotropy, mean diffusion, and radial diffusion of water varied significantly between the two dystrophic strains. Muscle structural differences were confirmed by histological analyses of the gastrocnemius, revealing a decreased muscle fiber size and increased fibrosis in skeletal muscle fibers of D2-mdx mice compared with B10-mdx and control. Cardiac involvement was also detected in D2-mdx myocardium based on both decreased function and myocardial T2. These data indicate that MR parameters may be used as sensitive biomarkers to detect fibrotic tissue deposition and fiber atrophy in dystrophic strains.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a progressive and life-threatening X-linked muscular disorder caused by mutations in the dystrophin (dys) gene. The dys gene encodes a 427-kDa cytoskeletal protein that forms the dystrophin/glycoprotein complex at the sarcolemma with sarcoglycans, dystroglycans, and other proteins, and links the cytoskeleton of myofibers to the extracellular matrix in skeletal muscle. The lack of dystrophin perturbs the dystrophin/glycoprotein complex assembly and causes instability of the muscle membrane, leading to muscle degeneration and myofiber loss. The disease progression in DMD is characterized by degeneration, necrosis, accumulation of fat and fibrosis, and insufficient regeneration of myofibers accompanied by a loss of myofibers.

Animal models have helped advance the understanding of the underlying pathological changes that occur in the muscular dystrophies. The histopathological findings associated with mutation in the dys gene are similar in both human patients and the murine models of muscular dystrophy.1, 2, 3, 4 Although the mdx mouse model is one of the most commonly used animal models for DMD, it has a milder phenotype compared with patients with DMD.5, 6 Despite the fact that mdx mice display a milder skeletal muscle phenotype, they have been used to develop and demonstrate proof of principle for many therapeutic approaches, including gene therapy,7, 8 stop codon suppression drugs,9, 10 RNA splicing,11, 12 and stem cell therapies.13

Mounting evidence has uncovered the presence of genetic modifiers that lead to phenotypic variability even with an identical gene mutation.14, 15, 16, 17 Moreover, both mdx and a mouse model of limb girdle muscular dystrophy (Sgcg−/−) bred on the DBA/2J background display a more severe phenotype compared with other backgrounds,18, 19 suggesting a role of genetic modifiers in disease progression. In addition, evidence in the literature supports that animal models on the DBA/2J strain are more severely affected than C57BL10 and C57BL6 backgrounds.20, 21 In recent years, mdx mice on the DBA/2J background [ie, D2.B10-Dmdmdx (D2-mdx)] mouse model has emerged as an alternative mouse model, which has been proposed to parallel human disease progression more closely than the contemporary mdx mouse model on the BL10 background (ie, B10-mdx).18, 20 In addition, disease progression varies between individual muscles and is an important factor to consider in future and especially longitudinal studies.22, 23 This limitation can be overcome by using sensitive noninvasive imaging biomarkers.24, 25, 26, 27 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has emerged as a robust and sensitive tool that can be used to monitor natural disease progression and efficacy of therapeutic interventions.28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34

The skeletal muscles and myocardium contain a variety of tissues characterized by differences in proton transverse relaxation time constants (T2). These alterations in T2 have been attributed to muscle damage,35 edema,36, 37, 38 fatty tissue infiltration,39 and fibrosis.40, 41 Similar to skeletal muscle MRI, cardiac magnetic resonance has emerged as a sensitive diagnostic tool to detect cardiac dysfunction in DMD patients.42, 43, 44 Cardiac magnetic resonance is a noninvasive tool that allows three-dimensional volumetric measurement analysis to detect global cardiac functions and strain measures. Recent studies in infarcted/fibrotic cardiac tissue and in tissue phantoms have shown that both T2 and T2∗ are linearly related to collagen content and tissue fibrosis based on staining for collagen45 and hydroxyproline assay.46 Similar to the skeletal muscle, the mdx mouse model initially presents with a mild cardiac phenotype, but at older ages they progress to a dilated cardiomyopathy.47

The primary purpose of this study was to monitor the changes in skeletal and cardiac muscles of D2-mdx mice using MRI as a noninvasive biomarker, which is evolving as a new model for DMD that closely mimics the pathological changes occurring in DMD. Using MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy, we assessed longitudinal changes in muscle pathology and compared these longitudinal changes to age-matched control using DBA/2J and B10-mdx mice. Also, at a single age time point, we determined cardiac function and water diffusion in their skeletal muscles. Histological verification was made based on trichrome and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to quantify muscle fiber size changes and fibrotic tissue deposition in the skeletal muscles from each strain.

Materials and Methods

Animal Handling and Care

The study was conducted with the approval from the University of Florida (Gainesville) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Five-week-old, specific pathogen-free mice DBA/2J; DBA2 (n = 5 males), C57BL/10ScSn, C57BL10 (n = 5), C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx; B10-mdx (n = 5 males), and D2.B10-Dmdmdx;D2-mdx (n = 5 males) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and thereafter maintained in house until 7 months of age. Mice were fed ad libitum and were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International–accredited animal facility in a temperature (22°C ± 1°C), humidity (50% ± 10%), and light (12-hour light/dark cycle) controlled room.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Hindlimb Muscle Imaging

MRI was performed in a 4.7-T, horizontal bore magnet (VMJ version 3.1; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Throughout MRI, animals were anesthetized using an oxygen and isoflurane mixture (3% isoflurane) and maintained under 0.5% to 1% isoflurane while their respiratory rate was monitored (Small Animal Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). The lower hindlimbs of the mouse were inserted up to the knee into a 2.0-cm internal diameter, custom-built solenoid 1H coil (200 MHz). Three-dimensional gradient images were acquired with the following parameters: field of view (FOV), 15 × 15 × 15 mm3; matrix size, 256 × 192 × 96; repetition time (TR), 50 milliseconds; echo time (TE), 7 milliseconds; number of signal averages, 2; flip angle, 40 degrees. In addition, T2-weighted, multiple-slice, single spin-echo MR images were acquired with the following parameters: TR, 2000 milliseconds; TE, 14 and 40 milliseconds; FOV, 10 to 20 mm; slice thickness, 0.5 to 1 mm; acquisition matrix, 128 × 256; and number of signal averages, 2. Hahn spin echo was implemented to avoid the contribution of stimulated echoes in the T2 measurement.48 T2 was calculated assuming a single exponential decay.49 To eliminate the potential of lipid changes on T2 and increase TE sampling, 1H2O spectroscopic relaxometry was implemented using a single voxel within the posterior muscle compartment using stimulated echo acquisition mode under the following parameters: voxel size, 1.5 × 3.0 × 1.5 mm3; TR, 9000 milliseconds; 29 unequally spaced TEs from 5 to 200 milliseconds (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65, 70, 80, 90, 100, 110, 120, 130, 140, 150, 160, 170, and 200); mixing time, 20 milliseconds; and number of phased cycled averages, 4. Water amplitude as a function of TE was determined using complex principal component analysis, as previously described.50 The decay in water signal amplitude was fit to a single exponential decay.51 This allowed for the acquisition of highly TE-sampled T2 decay with high signal/noise ratio (approximately 4500), which was calculated as previously published.52, 53 Finally, spin-echo diffusion tensor image data were acquired using the following parameters: b-value, 900 seconds/mm2; TE/TR, 21/1000; and number of signal averages, 2. FOV, slice thickness/gap, and acquisition matrix were 20 × 20 mm2, 1 mm/0 mm, and 128 × 128, respectively, yielding a voxel resolution of 0.16 × 0.16 × 1.00 mm3. The signal/noise ratio of images with minimum b value was 29.25, and that with b = 900 seconds/mm2 is 13.11.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

After anesthesia, mice were positioned supine on a home-built setup that allowed monitoring of body temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate (Small Animal Instruments). The average body temperature of the mice was 34°C, and their respiratory rate was 50 to 60 breaths/minute. ECG electrodes were inserted in limbs of mice, and a respiration pad was taped across the abdomen. Mice were maintained under anesthesia (1% to 1.5%) via nose cone and were placed in a magnet. Body temperature was maintained using a regulated circulated water heater. The temperature of water was maintained between 45°C and 50°C. Mice were imaged using a 3.3-cm diameter quadrature birdcage volume coil. A series of five transverse images were acquired over the heart after power calibration and global shimming scans. Single-slice long axis axial and sagittal scans were acquired to view the apex and base of the heart. These long axis scans were used to obtain the short axis scans, which were then used to measure ventricular function. Left and right ventricles were imaged using a stack of short axis images with 1-mm slice thickness. Images were acquired using a spoiled gradient-echo cine sequence (TR, 110 milliseconds; TE, 1.37 milliseconds; flip angle, 15 degrees; FOV, 25 × 25 mm2; data matrix, 128 × 128; and slice thickness, 1 mm). Twelve cine frames were acquired through the cardiac cycle and were ECG triggered to R wave with R-R delay of 110 milliseconds and delay of 0.2 milliseconds. In addition, gated T2 weighted single spin echo images of the left ventricle in the short axis view were acquired using the following parameters: TR, 750 milliseconds; TE, 12 and 30 milliseconds; FOV, 25 × 25 mm2; slice thickness, 1.0 mm; acquisition matrix, 256 × 128; averages, 8. Short axis slices from the midpapillary region were selected to calculate mean T2.

Histology

Hindlimb muscles were carefully extracted and stored for further analyses. Specifically, posterior compartment muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) were extracted and embedded in TissueTek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and frozen using isopentane chilled in liquid nitrogen. Frozen sections (8 μm thick) were obtained from the mid belly region of gastrocnemius (GAS) muscle using a cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Solms, Germany). Multiple sections were taken and kept at room temperature for 20 to 30 minutes before staining them with H&E working solution (Surgipath, Buffalo Grove, IL). In addition, Masson trichrome staining was used to detect fibrotic tissue accumulation and was performed per manufacturer's instructions.

MR Analysis

Hindlimb Muscles

Images were converted to Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine format using a custom written IDL code for Varian data (Exelis, Colorado Springs, CO). Anterior and posterior compartments were outlined on axial images of the whole limb to determine maximum cross-sectional area (CSAmax) of individual compartments, as described previously.41, 54 Briefly, CSAmax was calculated as the mean of the consecutive three slices having the greatest CSA for both anterior and posterior compartments separately. Furthermore, muscle MR-T2 values of anterior and posterior compartments were computed and analyzed using T2 maps, generated from two echo times (TEs, 14 and 40 milliseconds) using OsiriX software version 3.9.4 (Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland), an open-source Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine viewer and analysis software. To improve the coverage and reliability, muscle MR-T2 values of the middle six to eight slices from the anterior and posterior compartments were computed. T2 was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where SI 14 and SI 40 are the pixel intensities at a TE of 14 and 40 milliseconds, respectively. Muscle water-only (1H2O-T2) data were analyzed using a custom written software in IDL (Exelis). Specifically, 1H2O-T2 was determined by a nonlinear curve fitting the decay in water signal as a function of TE using a monoexponential model and nonnegative least squares (Supplemental Figure S1).50, 55 Finally, using a validated56 IDL-based MRI analysis software version 00020170123 (http://marecilab.mbi.ufl.edu/software/MAS; last accessed March 30, 2017), mean diffusivity, radial diffusivity, fractional anisotropy (FA), and eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, λ3) were all determined within a region of interest in posterior compartment muscles (GAS-soleus complex). Mean diffusivity and radial diffusivity were calculated using (λ1 + λ2 + λ3/3) and (λ2 + λ3/2), respectively. After the last MR examination of the mice at 7 months of age, hindlimb muscles were extracted for histological examinations.

Myocardial Function

Left ventricular function was analyzed using cine images. Seven to eight series of frames were acquired covering the whole heart (apex to base of the heart). The end diastolic volume and end systolic volume were measured for each slice and summed over the whole heart. Stroke volume was calculated as: end diastolic volume − end systolic volume.

Furthermore, ejection fraction was calculated as stroke volume/end diastolic volume.

In addition, left ventricular mass was calculated using myocardial area × slice thickness × myocardial density (1.05).57, 58 Finally, mean myocardial T2 was calculated using the average signal intensity at each TE by manually tracing the myocardium, at the midsection of the heart, using OsiriX software.

H&E Staining and Trichrome Stains

Slides were imaged using a digital camera (Leica Microsystems) and analyzed using ImageJ software version 1.48v (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). The average muscle fiber size was determined by using a similar approach as described previously.54 Cryostat sections (8 to 10 μm thick) in a transverse plane were cut in the middle section of the muscle and stained with H&E stains. Stained cross sections were imaged using a Leica fluorescence microscope with a digital camera. Muscle fiber cross section area was measured using NIH ImageJ software. All of the muscle fibers were circled, and fiber area was recorded for 150 to 200 muscle fibers.

In addition, fibrotic area was quantified by dividing fibrotic tissue (blue stain) by the total cross-sectional area of the entire tissue section.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA) and included one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey multiple comparisons test. In addition, a paired t-test was used to demonstrate age-dependent changes in anterior and posterior compartment muscles. All data are presented as means ± SD, unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Reduced Body and Muscle Weight in D2-mdx Mice

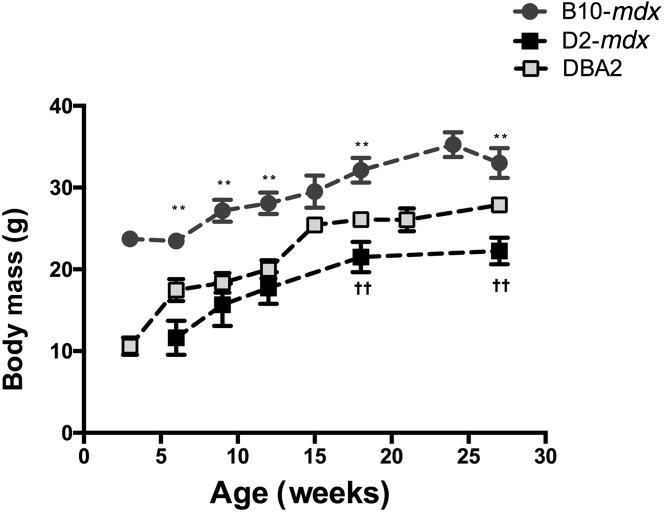

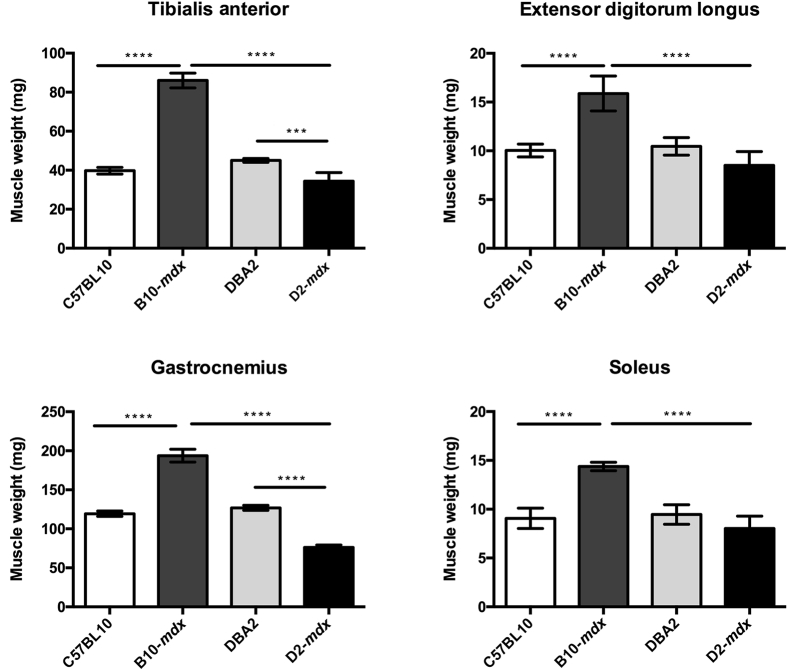

As an overall measure of animal health, we monitored the body weight of all animals on a weekly basis. Although there was an age-dependent increase in body weight in all of the groups, B10-mdx weighed more than D2-mdx and DBA2 mice at all ages (Figure 1) (P < 0.01). At the 7-month time point, hindlimb muscles (tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, GAS, and soleus) of D2-mdx mice were all extracted and weighed (Figure 2). The tibialis anterior and GAS of D2-mdx mice weighed significantly less than the equivalent muscles from B10-mdx mice (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Body mass reduction in D2-mdx mice compared with B10-mdx mice at all time points. In addition, after 15 weeks of age, D2-mdx mice weigh significantly less than age-matched DBA2 mice. ∗∗P < 0.01 between B10-mdx and D2-mdx; ††P < 0.01 between DBA2 and D2-mdx muscles.

Figure 2.

Muscle wet weight of different muscles at age of 7 months, showing significant differences among different groups. Data are expressed as means ± SD. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

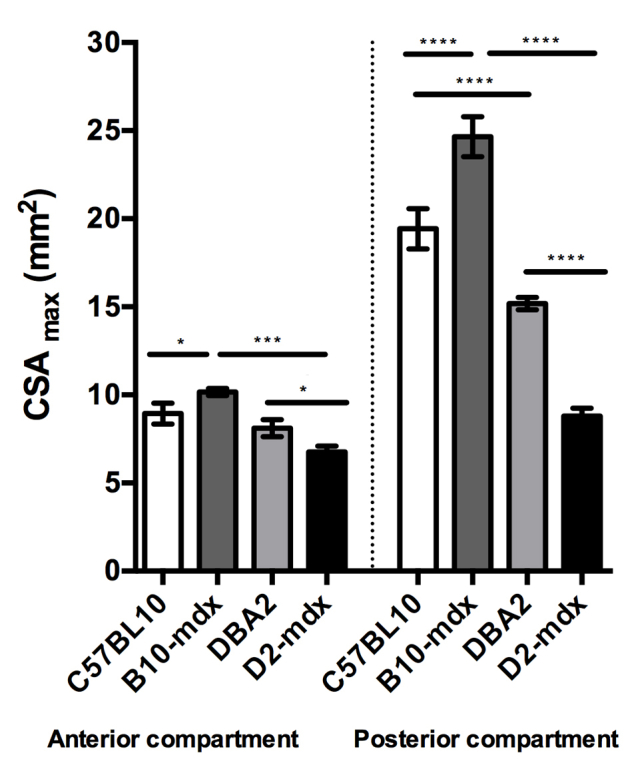

Reduced Muscle CSAmax

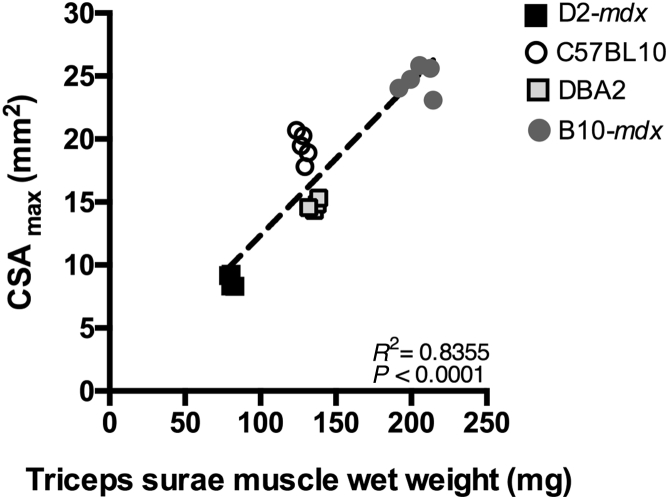

MRI was implemented to quantify in vivo differences in muscle size in the different experimental groups. CSAmax values of anterior and posterior compartment muscles were compared among different groups at the 26-week time point (Supplemental Figure S2). In addition, the relationship between CSAmax (posterior compartment) and muscle wet weight (sum of GAS and soleus) obtained at the 7-month time point was determined. A strong correlation (r = 0.97) was found between two measures (Figure 3) and further illustrates the small muscle masses in D2-mdx mice.

Figure 3.

Correlation between wet weight and CSAmax of triceps surae muscles of D2-mdx, C57BL10, DBA2, and BL10-mdx mice at 7 months of age.

Age-Dependent Alterations in Muscle T2

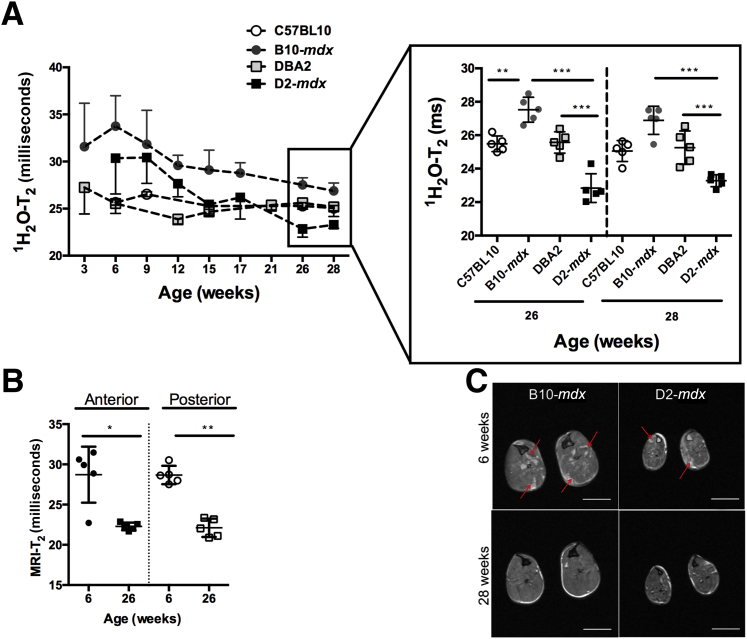

The magnetic resonance spectroscopy–determined water T2 (1H2O-T2) values clearly revealed differences between the different mouse cohorts (Figure 4A). Of interest was the rapid decline in mdx-dba muscle T2 values significantly below that of DBA-2 at 26 weeks of age. Although B10-mdx muscles also decreased over this period, they did not decrease below the level of C57BL10 1H2O-T2, even at the oldest ages that were measured in this study (Figure 4). At 6 months of age, 1H2O-T2 values were significantly (P = 0.001) reduced in both B10-mdx (27.5 ± 0.8 milliseconds) and D2-mdx (22.8 ± 0.9 milliseconds) mice compared with their baseline measurement at 6 weeks of age (B10-mdx, 33.8 ± 3.2 milliseconds; D2-mdx, 30.4 ± 3.8 milliseconds). At 6 months of age, B10-mdx demonstrated significantly higher 1H2O-T2 than age-matched C57BL10 (27.5 ± 0.8 versus 25.15 ± 0.34 milliseconds; data not shown). Interestingly, after 6 months of age, D2-mdx mice showed significantly reduced 1H2O-T2 values compared with control DBA2 mice (D2-mdx versus DBA2, 22.8 ± 0.9 versus 25.6 ± 0.7 milliseconds; P < 0.005). Natural history changes in muscle T2 (MRI-T2) demonstrate an age-dependent decline in T2 in D2-mdx mice. MRI-T2 values from anterior and posterior compartments of D2-mdx mice were significantly reduced at the 26-week time point (means ± SD; anterior compartment, 22.3 ± 0.5 milliseconds; posterior compartment, 22.1 ± 1.1 milliseconds; P < 0.01) compared with the 6-week time point (anterior compartment, 28.7 ± 3.5 milliseconds; posterior compartment, 28.7 ± 1.2 milliseconds; P < 0.01) (Figure 4B), which are demonstrated as a decrease in hyperintense areas on T2-weighted axial images (Figure 4C). On the contrary, we did not find any significant age-dependent decrease in MRI-T2 of C57BL10 muscles between the ages of 6 and 26 weeks (anterior compartment, 23.52 ± 1.0 versus 22.9 ± 0.6 milliseconds; posterior compartment, 24.8 ± 0.8 versus 23.4 ± 0.8 milliseconds).

Figure 4.

A: Time course of 1H2O-T2 changes in posterior hindlimb muscles of B10-mdx, DBA2, and D2-mdx mice. In addition, significant differences are seen among groups at 26 and 28 weeks of age. B: Longitudinal MRI-T2 of anterior and posterior compartment muscles of D2-mdx mice, demonstrating a significant decrease at 26 weeks of age. C: Axial T2-weighted MR images of B10-mdx and D2-mdx mice, aged 6 and 28 weeks, showing presence of hyperintense areas in anterior and posterior compartment at 6 weeks of age (red arrows), but these hyperintense areas are absent at 28 weeks of age. In addition, both B10-mdx and D2-mdx demonstrate significant differences in the size of the anterior and posterior hindlimb muscle compartments. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bar = 2 mm (C).

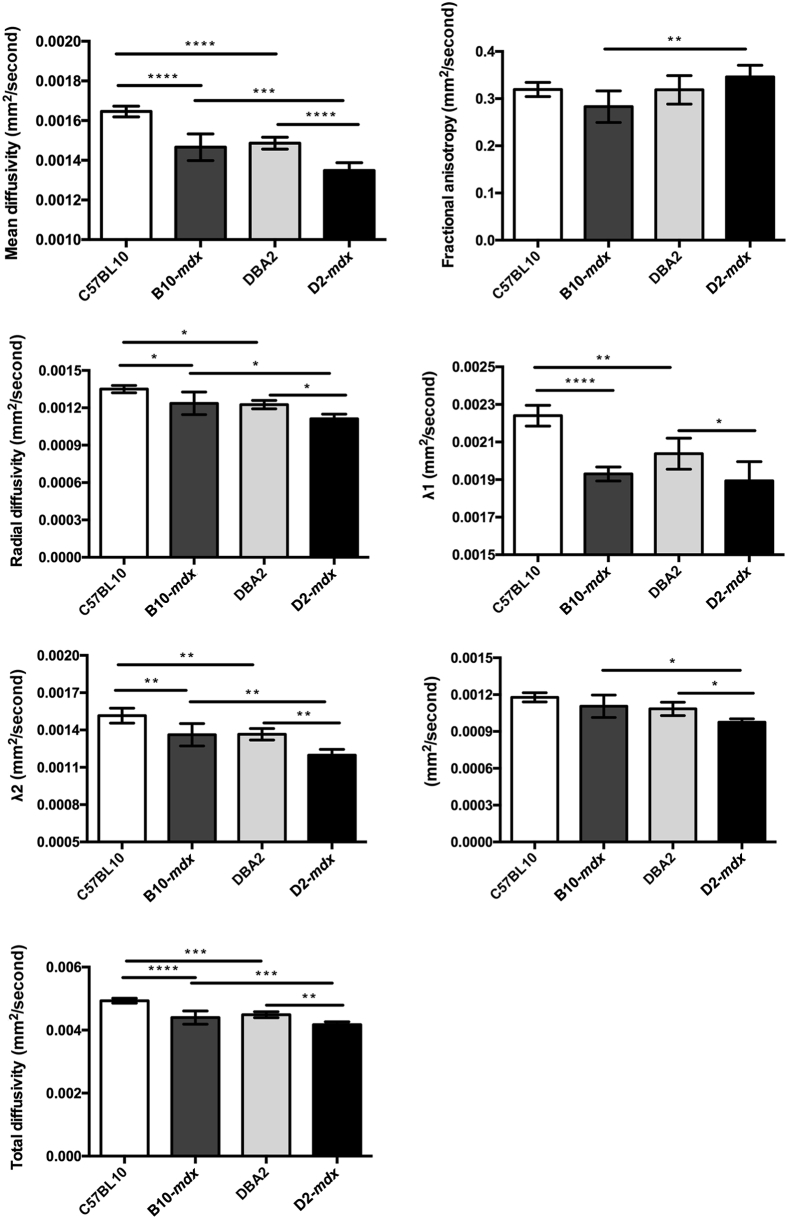

Strain-Dependent Differences in Muscle Diffusion

At 7 months of age, we performed diffusion tensor measurements in C57BL10, B10-mdx, DBA2, and D2-mdx mice (Figure 5). The mean diffusivity was significantly reduced in both dystrophic models compared with their strain-dependent controls [ie, B10-mdx (1.4 × 10−3 ± 5.7 × 10−5 mm2/second) versus C57BL10 (1.6 ×10−3 ± 2.7 × 10−5 mm2/second) and D2-mdx muscles (1.3 × 10−3 ± 4.0 × 10−5 mm2/second) versus DBA2 (1.5 × 10−3 ± 3.0 × 10−5 mm2/second) mice]. In addition, D2-mdx mice had significantly higher FA compared with B10-mdx mice (0.35 ± 0.02 versus 0.28 ± 0.03; P < 0.001). We did not find any difference in FA values of C57BL10 and B10-mdx (0.32 ± 0.02 versus 0.28 ± 0.03). Finally, radial diffusion was significantly reduced in D2-mdx compared with B10-mdx (1.1 × 10−3 ± 3.7 × 10−5 versus 1.2 × 10−3 ± 9.0 × 10−5 mm2/second) mice at 7 months of age.

Figure 5.

Diffusion tensor image parameters demonstrating significant differences among different groups. Data are expressed as means ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

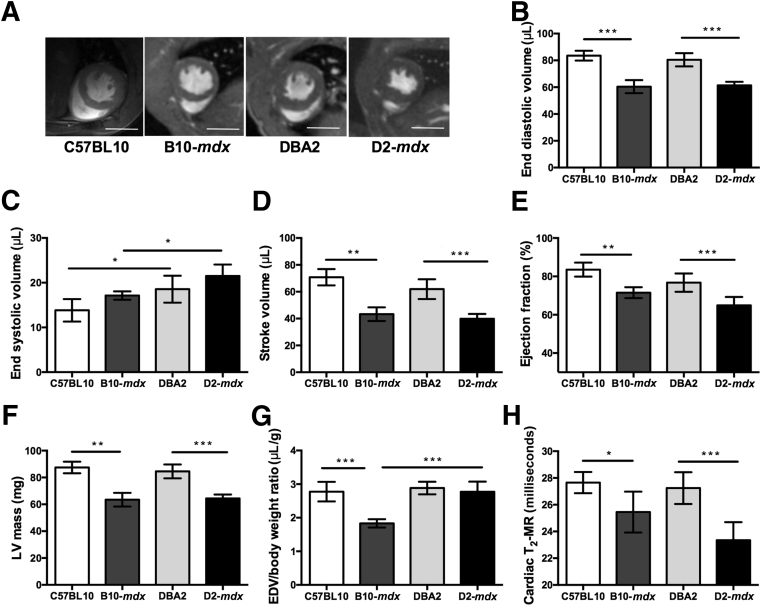

Decrease in Cardiac Function in D2-mdx Mice

At 7 months of age, D2-mdx mice demonstrated a significant decrease in cardiac function compared with B10-mdx and DBA2 mice (Figure 6A). We did not find any significant differences in myocardial functional measurements of dystrophic mice groups [stroke volume (B10-mdx versus D2-mdx), 43.3 ± 5.1 μL versus 39.84 ± 3.6 μL; % ejection fraction (B10-mdx versus D2-mdx), 71.5% ± 2.8% versus 64.9% ± 4.4%; and left ventricular mass (B10-mdx versus D2-mdx), 63.4 ± 5.1 mg versus 64.4 ± 2.8 mg] (Figure 6, B–G). However, these measurements were significantly different between D2-mdx and DBA2 myocardium (stroke volume, 39.8 ± 3.6 μL versus 61.9 ± 7.4 μL; % ejection fraction, 64.9% ± 4.4% versus 76.7% ± 4.8%; left ventricular mass, 64.4 ± 2.8 mg versus 84.5 ± 5.2 mg). Furthermore, normalized end diastolic volume/body weight ratio in D2-mdx mice was significantly higher compared with B10-mdx mice. Finally, myocardial T2 of D2-mdx mice compared with DBA2 mice was significantly decreased (23.3 ± 1.3 milliseconds versus 27.2 ± 1.4 milliseconds; P < 0.01) (Figure 6H). We did not find any significant difference between B10-mdx and D2-mdx mice at this age.

Figure 6.

A: Representative two-chamber short axis cine slices at the level of papillary muscles at the end diastole in C57BL10, B10-mdx, DBA2, and D2-mdx mice. B–G: Cardiac functional data demonstrating significant differences between dystrophic mice on different background strain. H: Myocardium T2 reveals significant differences in DBA2 and D2-mdx mice. Data are expressed as means ± SD (B–H). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bar = 10 mm (A). EDV, end diastolic volume; LV, left ventricular.

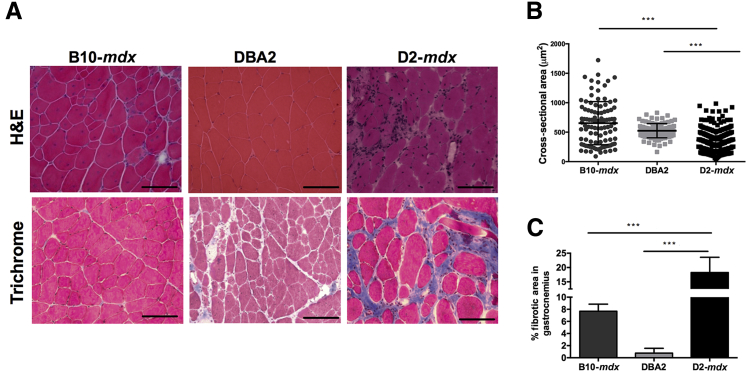

Histological Measurements

Muscle cryosections from D2-mdx, DBA/2, and B10-mdx mice were stained with H&E stains and quantified for fiber cross-sectional area, and the fibrotic tissue accumulation was quantified using Masson trichrome stain (Figure 7A). D2-mdx mice demonstrated a significantly (P < 0.001) decreased fiber cross-sectional area compared with DBA2 and B10-mdx mice (Figure 7B). In comparison to DBA/2 and B10-mdx muscles, D2-mdx muscles exhibited significantly increased fibrosis (DBA2 versus D2-mdx, 0.76% versus 18.24%; P < 0.001) (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

A: H&E and trichrome stains of gastrocnemius muscle of B10-mdx, DBA2, and D2-mdx mice showing decrease in fiber size and increase in fibrotic tissue accumulation. B: D2-mdx mice have significantly reduced fiber cross-sectional areas compared with B10-mdx and DBA2 mice. C: Increased fibrotic tissue accumulation in gastrocnemius muscle of D2-mdx mice compared with B10-mdx. Data are expressed as means ± SD (B and C). ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bar = 100 μm (A). Original magnification, ×20 (A).

Discussion

In this study, we compared changes in MR parameters of skeletal and cardiac muscles in mdx mice on two different genetic backgrounds (BL/10 and DBA/2J), known to exhibit vastly different levels of tissue fibrosis.20, 59 We observed the following: i) a decrease in CSAmax of hindlimb muscles of D2-mdx compared with B10-mdx, ii) an accelerated age-dependent decrease in skeletal and cardiac muscle T2 in D2-mdx mice compared with B10-mdx, iii) differences in diffusion parameters in D2-mdx mice compared with B10/mdx mice, in which these differences were related to differences in muscle fiber size, and iv) impaired cardiac functional measurements in D2-mdx mice compared with age-matched B10-mdx and DBA2 mice.

The mdx mouse (C57BL/10-DMDmdx) model, on the C57BL/10ScSn background, has been the most widely used preclinical mouse model of DMD. Although dystrophin is absent in both DMD patients and the mdx mouse model, the severity of disease varies considerably. In contrast to DMD, most hindlimb muscles of the mdx mouse maintain skeletal muscle mass throughout much of their lifespan. Therefore, absence of dystrophin solely as the underlying cause of DMD fails to explain the variability in the disease progression. An increased body of evidence suggests that patients with DMD with the same mutation show marked differences in motor severity, implying the presence of genetic and environmental modifiers in muscular dystrophies that lead to considerable variability in disease progression.17, 60 One source of this variation has been attributed to the presence of the Ltbp4 gene encoding the latent transforming growth factor-β binding protein 4 as a strong modifier of muscular dystrophy in both mice and humans.60, 61

Studies have shown that specific mutations in the D2 strain make them more susceptible to age-related hearing loss, glaucoma, and calcified lesions of the testes, tongue, and skeletal muscles.62, 63 In addition, there has been a growing body of evidence demonstrating an increase in pathology and fibrosis in dystrophic mice on the DBA/2J background compared with other backgrounds.19 Indeed, studies have reported a decrease in body weight and muscle weight in mdx mice on the DBA/2J background.18, 20 Moreover, Heydemann et al19 reported that γ-sarcoglycan null mice on the DBA/2 background showed decreased skeletal muscle weight, increased Evans Blue uptake, and higher hydroxyproline content than C57BL/6, CD1, and 129 backgrounds. Similarly, in this study, we have found that D2-mdx mice were much smaller compared with control mice on the DBA background and B10-mdx mice. These data are consistent with the previously published studies showing that D2-mdx mice depict an atrophic phenotype.20 MRI has been used to quantify muscle volume as well as CSAmax.54, 64 Using MRI as a noninvasive biomarker, we demonstrated that D2-mdx mice had significantly reduced CSAmax of both anterior and posterior compartment muscles compared with age-matched B10-mdx and DBA/2J mice. MRI's noninvasive nature offers a unique opportunity to evaluate therapeutic measures aimed at increasing muscle mass, such as myostatin inhibitors or growth hormones in the same animal to address efficacy using the D2-mdx model.

The DBA/2J strain has been shown to be prone to extensive calcification in the presence of cardiac and skeletal muscle fibrosis.18 In the present study, we demonstrate that skeletal and cardiac muscles of D2-mdx mice display lower T2 values compared with B10-mdx mice. It has been well established that B10-mdx mice show increased fibrosis in the diaphragm by 6 months of age.65 Fibrotic tissue accumulation in hindlimb muscles increases significantly in old mdx mice.59 MRI has been used to measure reduced signal intensity, which correlates with increase in fibrosis in heart66 and skeletal muscles.41 In this study, D2-mdx mice displayed decreased skeletal and cardiac muscle T2 values earlier in life compared with B10-mdx mice, and this decreased T2 was associated with an increase in tissue fibrosis. In addition, a recent publication by Coley et al18 demonstrated that D2-mdx mice develop signs of cardiomyopathy much earlier than B10-mdx mice. Similar to the previously published results,18 we also found a decrease in cardiac function and myocardial T2 of D2-mdx mice at 7 months of age compared with B10-mdx and age-matched controls. In combination, both skeletal and cardiac muscles of D2-mdx mice exhibit accelerated age-dependent changes in fibrosis and function.

We further evaluated changes in water diffusivity in the presence of decreased muscle fiber size and fibrosis. Diffusion tensor image–based MR methods have been previously used to demonstrate variations in dystrophic muscle67, 68 and denervation models.64 It has been previously proposed that the change in eigenvalues and FA is indicative of change in muscle fiber morphology.69 Specifically, the principle eigenvalue (λ1) coincides with the long axis of the fibers,70, 71 λ2 represents diffusion within the endomysium, and λ3 represents diffusion within the cross section of a muscle fiber.72 Correspondingly, we found that diffusion parameters in D2-mdx muscles were different compared with B10-mdx and control DBA2 mice. An increase in the degree of restricted diffusion of water may indicate change in the muscle architecture.69, 73, 74 Using the D2-mdx mouse model, we found that there was a decrease in both the mean diffusivity and radial diffusivity. Previously, using an injury model in mdx mice, McMillan et al68 have demonstrated that with increase in edema there is increase in diffusion parameters, increase in muscle T2, and decrease in FA. Interestingly, in D2-mdx muscles, at 7 months of age, we found that T2 and diffusion parameters decreased, whereas there was an increase in FA. Histologically, we observed an increase in fibrous/collagenous tissue deposition and a decrease in muscle fiber size, suggesting a fibrotic and atrophic phenotype in D2-mdx mice. Our histological results are in agreement with previously published results, where they demonstrated that D2-mdx mice displayed a decrease in mean fiber CSA, which can significantly affect skeletal muscle diffusion tensor image–MR measurements in mice at long diffusion times.18 In addition, we observed accumulation in fibrotic/collagenous material around the muscle fibers, which could contribute to a decrease in λ2. Previous studies have also reported an increase in fibrotic material in dystrophic mice on the DBA/2J background.61 Finally, we have demonstrated a decrease in λ3 eigenvalue, which is hypothesized to correspond to muscle fiber size.75 In support of the MR results, we correlated the MRI findings with histological measures and found that there is a decrease in muscle fiber size but also an increase in fibrotic tissue accumulation. These results are somewhat surprising because the diffusion times used in this study are relatively short, precluding the measurement of fiber diameter, possibly indicating that increased intracellular diffusive barriers exist in the D2-mdx muscles. Future studies using variable b values and diffusion times or magnetic resonance spectroscopy–based diffusion measurements could help provide insight.76 Results of previous studies have also shown a decrease in muscle fiber size of D2-mdx muscles compared with B10-mdx muscles.18, 20

An increased body of evidence suggests a decrease in cardiac function with age in dystrophic mice.18, 77 Similarly, our evaluations revealed significant differences in stroke volume and ejection fraction between dystrophic mice (ie, B10-mdx and D2-mdx and their age- and strain-matched control mice). However, we did not find significant differences between B10-mdx and D2-mdx mice at 7 months of age. One of the reasons is that the cardiac muscles in B10-mdx mice are also affected between ages of 6 and 9 months. Furthermore, a study by Ballmann et al38 demonstrated that cardiac magnetic resonance T2 can detect beneficial effects of long-term dietary quercetin enrichment. In addition, fibrotic tissue accumulation has been demonstrated in dystrophic myocardium.77 Fibrotic tissue accumulation is an important feature in muscular dystrophy. Finally, we found a decrease in myocardium T2 in both dystrophic strains at 7 months of age. Further exploration of the genetic and physiological differences between the two dystrophic strains is warranted.

It is important to consider the limitations of this study. First, there are a multitude of underlying factors that coexist in dystrophic muscles. For example, change in muscle permeability, loss of external or internal fibers, and/or reduction in fiber diameter are some factors, and these changes can be measured using range of diffusion time, ranging from 80 to 200 milliseconds.76 Another limitation of the study is the use of different b values compared with previously published values. Previously published studies have used a b value of 400 to 500 seconds/mm2,64, 73, 75 whereas in the present study, we have used a b value of 900 seconds/mm2. The signal/noise ratio of images with a minimum b value was 29.11, which is close to the previously published studies.64 However, in this study, we were unable to use the advanced diffusion techniques to measure cell structure and dimensions, which should be incorporated in the future studies to corroborate MR results. Another limitation of this study is the absolute quantification of fibrotic tissue accumulation in myocardium in dystrophic mice using MRI. However, studies in the past have demonstrated that myocardium T2 can be used as a surrogate measure to monitor fibrotic tissue accumulation.45 Despite all of the limitations, we hope our study forms a platform for future studies using advanced MR methods to demonstrate the inherent differences between dystrophic mice on different backgrounds.

In summary, we demonstrate that mdx mice on the DBA background show increased skeletal muscle and cardiac pathology compared with the BL/10 background. Furthermore, MRI of skeletal and cardiac muscle was found to be able to differentiate between these models and may prove to be a sensitive surrogate measure for detecting the underlying pathophysiological changes in mouse models of dystrophy. In addition to MRI being a noninvasive measure, it can be serially applied to the same animal, as in this study, and may help to reduce cost and achieve the wanted statistical power for preclinical therapeutic screening with fewer animals.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH Paul D. Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research grant U54AR052646 (G.A.W.) and Department of Defense grant MD110050 (G.A.W.). A portion of this work was performed in the McKnight Brain Institute at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory's Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy Facility, which is supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement DMR-1157490 and the state of Florida.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.05.010.

Supplemental Data

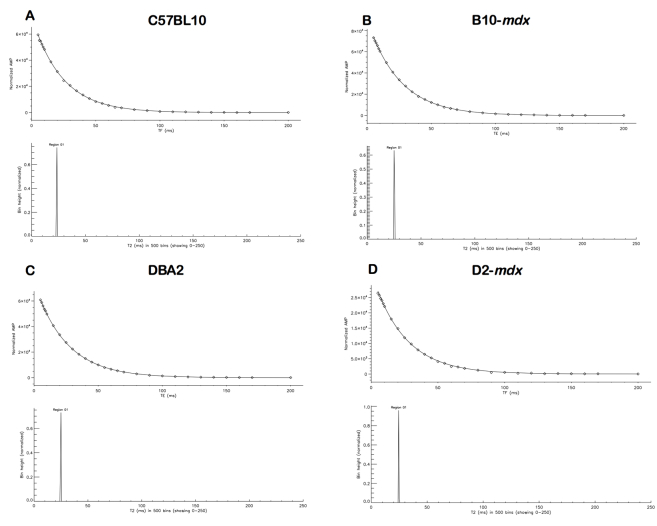

Supplemental Figure S1.

The T2–nonnegative least squares (NNLS) spectrum of muscle from C57BL10 (A), B10-mdx (B), DBA2 (C), and D2-mdx (D) mice. The NNLS spectrum exhibits a single relaxation peak between 20 and 30 milliseconds. AMP, amplitude; TE, echo time.

Supplemental Figure S2.

Decrease in CSAmax of muscles of the anterior and posterior compartments of hindlimb muscles of D2-mdx mice at 7 months of age. Data are expressed as means ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

References

- 1.Bonnemann C.G., McNally E.M., Kunkel L.M. Beyond dystrophin: current progress in the muscular dystrophies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1996;8:569–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allamand V., Campbell K.P. Animal models for muscular dystrophy: valuable tools for the development of therapies. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2459–2467. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastoret C., Sebille A. mdx Mice show progressive weakness and muscle deterioration with age. J Neurol Sci. 1995;129:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)00276-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell C.D., Conen P.E. Histopathological changes in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1968;7:529–544. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(68)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pons F., Robert A., Fabbrizio E., Hugon G., Califano J.C., Fehrentz J.A., Martinez J., Mornet D. Utrophin localization in normal and dystrophin-deficient heart. Circulation. 1994;90:369–374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banks G.B., Chamberlain J.S. The value of mammalian models for duchenne muscular dystrophy in developing therapeutic strategies. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;84:431–453. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregorevic P., Blankinship M.J., Allen J.M., Crawford R.W., Meuse L., Miller D.G., Russell D.W., Chamberlain J.S. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox G.A., Cole N.M., Matsumura K., Phelps S.F., Hauschka S.D., Campbell K.P., Faulkner J.A., Chamberlain J.S. Overexpression of dystrophin in transgenic mdx mice eliminates dystrophic symptoms without toxicity. Nature. 1993;364:725–729. doi: 10.1038/364725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welch E.M., Barton E.R., Zhuo J., Tomizawa Y., Friesen W.J., Trifillis P. PTC124 targets genetic disorders caused by nonsense mutations. Nature. 2007;447:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature05756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton-Davis E.R., Cordier L., Shoturma D.I., Leland S.E., Sweeney H.L. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:375–381. doi: 10.1172/JCI7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muntoni F., Wells D. Genetic treatments in muscular dystrophies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:590–594. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282efc157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood M.J., Gait M.J., Yin H. RNA-targeted splice-correction therapy for neuromuscular disease. Brain. 2010;133:957–972. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gussoni E., Soneoka Y., Strickland C.D., Buzney E.A., Khan M.K., Flint A.F., Kunkel L.M., Mulligan R.C. Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature. 1999;401:390–394. doi: 10.1038/43919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beggs A.H., Hoffman E.P., Snyder J.R., Arahata K., Specht L., Shapiro F., Angelini C., Sugita H., Kunkel L.M. Exploring the molecular basis for variability among patients with Becker muscular dystrophy: dystrophin gene and protein studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49:54–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muntoni F., Gobbi P., Sewry C., Sherratt T., Taylor J., Sandhu S.K., Abbs S., Roberts R., Hodgson S.V., Bobrow M. Deletions in the 5' region of dystrophin and resulting phenotypes. J Med Genet. 1994;31:843–847. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.11.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sifringer M., Uhlenberg B., Lammel S., Hanke R., Neumann B., von Moers A., Koch I., Speer A. Identification of transcripts from a subtraction library which might be responsible for the mild phenotype in an intrafamilially variable course of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Genet. 2004;114:149–156. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNally E.M., Passos-Bueno M.R., Bonnemann C.G., Vainzof M., de Sa Moreira E., Lidov H.G., Othmane K.B., Denton P.H., Vance J.M., Zatz M., Kunkel L.M. Mild and severe muscular dystrophy caused by a single gamma-sarcoglycan mutation. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:1040–1047. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coley W.D., Bogdanik L., Vila M.C., Yu Q., Van Der Meulen J.H., Rayavarapu S., Novak J.S., Nearing M., Quinn J.L., Saunders A., Dolan C., Andrews W., Lammert C., Austin A., Partridge T.A., Cox G.A., Lutz C., Nagaraju K. Effect of genetic background on the dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:130–145. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heydemann A., Huber J.M., Demonbreun A., Hadhazy M., McNally E.M. Genetic background influences muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2005;15:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukada S., Morikawa D., Yamamoto Y., Yoshida T., Sumie N., Yamaguchi M., Ito T., Miyagoe-Suzuki Y., Takeda S., Tsujikawa K., Yamamoto H. Genetic background affects properties of satellite cells and mdx phenotypes. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2414–2424. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelman R., Watson A., Bronson R., Yunis E. Murine chromosomal regions correlated with longevity. Genetics. 1988;118:693–704. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.4.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutpell K.M., Hrinivich W.T., Hoffman L.M. Skeletal muscle fibrosis in the mdx/utrn+/- mouse validates its suitability as a murine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arpan I., Forbes S.C., Lott D.J., Senesac C.R., Daniels M.J., Triplett W.T., Deol J.K., Sweeney H.L., Walter G.A., Vandenborne K. T(2) mapping provides multiple approaches for the characterization of muscle involvement in neuromuscular diseases: a cross-sectional study of lower leg muscles in 5-15-year-old boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:320–328. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pillen S., Tak R.O., Zwarts M.J., Lammens M.M., Verrijp K.N., Arts I.M., van der Laak J.A., Hoogerbrugge P.M., van Engelen B.G., Verrips A. Skeletal muscle ultrasound: correlation between fibrous tissue and echo intensity. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009;35:443–446. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arts I.M., Schelhaas H.J., Verrijp K.C., Zwarts M.J., Overeem S., van der Laak J.A., Lammens M.M., Pillen S. Intramuscular fibrous tissue determines muscle echo intensity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:449–450. doi: 10.1002/mus.22254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaidman C.M., Wang L.L., Connolly A.M., Florence J., Wong B.L., Parsons J.A., Apkon S., Goyal N., Williams E., Escolar D., Rutkove S.B., Bohorquez J.L., DART-EIM Clinical Evaluators Consortium Electrical impedance myography in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and healthy controls: a multicenter study of reliability and validity. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52:592–597. doi: 10.1002/mus.24611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez B., Li J., Yim S., Pacheck A., Widrick J.J., Rutkove S.B. Evaluation of electrical impedance as a biomarker of myostatin inhibition in wild type and muscular dystrophy mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreiber A., Smith W.L., Ionasescu V., Zellweger H., Franken E.A., Dunn V., Ehrhardt J. Magnetic resonance imaging of children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Radiol. 1987;17:495–497. doi: 10.1007/BF02388288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu G.C., Jong Y.J., Chiang C.H., Jaw T.S. Duchenne muscular dystrophy: MR grading system with functional correlation. Radiology. 1993;186:475–480. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.2.8421754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbiroli B., McCully K.K., Iotti S., Lodi R., Zaniol P., Chance B. Further impairment of muscle phosphate kinetics by lengthening exercise in DMD/BMD carriers: an in vivo 31P-NMR spectroscopy study. J Neurol Sci. 1993;119:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang Y., Majumdar S., Genant H.K., Chan W.P., Sharma K.R., Yu P., Mynhier M., Miller R.G. Quantitative MR relaxometry study of muscle composition and function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;4:59–64. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880040113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathur S., Lott D.J., Senesac C., Germain S.A., Vohra R.S., Sweeney H.L., Walter G.A., Vandenborne K. Age-related differences in lower-limb muscle cross-sectional area and torque production in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1051–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinali M., Arechavala-Gomeza V., Cirak S., Glover A., Guglieri M., Feng L., Hollingsworth K.G., Hunt D., Jungbluth H., Roper H.P., Quinlivan R.M., Gosalakkal J.A., Jayawant S., Nadeau A., Hughes-Carre L., Manzur A.Y., Mercuri E., Morgan J.E., Straub V., Bushby K., Sewry C., Rutherford M., Muntoni F. Muscle histology vs MRI in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2011;76:346–353. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318208811f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arpan I., Willcocks R.J., Forbes S.C., Finkel R.S., Lott D.J., Rooney W.D., Triplett W.T., Senesac C.R., Daniels M.J., Byrne B.J., Finanger E.L., Russman B.S., Wang D.J., Tennekoon G.I., Walter G.A., Sweeney H.L., Vandenborne K. Examination of effects of corticosteroids on skeletal muscles of boys with DMD using MRI and MRS. Neurology. 2014;83:974–980. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathur S., Vohra R.S., Germain S.A., Forbes S., Bryant N.D., Vandenborne K., Walter G.A. Changes in muscle T2 and tissue damage after downhill running in mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43:878–886. doi: 10.1002/mus.21986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant N.D., Li K., Does M.D., Barnes S., Gochberg D.F., Yankeelov T.E., Park J.H., Damon B.M. Multi-parametric MRI characterization of inflammation in murine skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed. 2014;27:716–725. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan R.H., Does M.D. Compartmental relaxation and diffusion tensor imaging measurements in vivo in lambda-carrageenan-induced edema in rat skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:566–573. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballmann C., Denney T.S., Beyers R.J., Quindry T., Romero M., Amin R., Selsby J.T., Quindry J.C. Lifelong quercetin enrichment and cardioprotection in Mdx/Utrn+/- mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312:H128–H140. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00552.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elder C.P., Apple D.F., Bickel C.S., Meyer R.A., Dudley G.A. Intramuscular fat and glucose tolerance after spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:711–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bo Li Z., Zhang J., Wagner K.R. Inhibition of myostatin reverses muscle fibrosis through apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3957–3965. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vohra R., Accorsi A., Kumar A., Walter G., Girgenrath M. Magnetic resonance imaging is sensitive to pathological amelioration in a model for laminin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy (MDC1A) PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puchalski M.D., Williams R.V., Askovich B., Sower C.T., Hor K.H., Su J.T., Pack N., Dibella E., Gottliebson W.M. Late gadolinium enhancement: precursor to cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy? Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;25:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9352-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hor K.N., Taylor M.D., Al-Khalidi H.R., Cripe L.H., Raman S.V., Jefferies J.L., O'Donnell R., Benson D.W., Mazur W. Prevalence and distribution of late gadolinium enhancement in a large population of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: effect of age and left ventricular systolic function. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:107. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florian A., Ludwig A., Engelen M., Waltenberger J., Rosch S., Sechtem U., Yilmaz A. Left ventricular systolic function and the pattern of late-gadolinium-enhancement independently and additively predict adverse cardiac events in muscular dystrophy patients. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:81. doi: 10.1186/s12968-014-0081-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Nierop B.J., Bax N.A., Nelissen J.L., Arslan F., Motaal A.G., de Graaf L., Zwanenburg J.J., Luijten P.R., Nicolay K., Strijkers G.J. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis in mice using a T2*-weighted 3D radial magnetic resonance imaging sequence. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Egger C., Gerard C., Vidotto N., Accart N., Cannet C., Dunbar A., Tigani B., Piaia A., Jarai G., Jarman E., Schmid H.A., Beckmann N. Lung volume quantified by MRI reflects extracellular-matrix deposition and altered pulmonary function in bleomycin models of fibrosis: effects of SOM230. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306:L1064–L1077. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00027.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinlan J.G., Hahn H.S., Wong B.L., Lorenz J.N., Wenisch A.S., Levin L.S. Evolution of the mdx mouse cardiomyopathy: physiological and morphological findings. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14:491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martins-Bach A.B., Malheiros J., Matot B., Martins P.C., Almeida C.F., Caldeira W., Ribeiro A.F., Loureiro de Sousa P., Azzabou N., Tannus A., Carlier P.G., Vainzof M. Quantitative T2 combined with texture analysis of nuclear magnetic resonance images identify different degrees of muscle involvement in three mouse models of muscle dystrophy: mdx, Largemyd and mdx/Largemyd. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu E.W., Schoeniger J.S., Bowtell R., Aiken N.R., Horsman A., Blackband S.J. A modified imaging sequence for accurate T2 measurements using NMR microscopy. J Magn Reson B. 1995;109:66–69. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Triplett W.T., Baligand C., Forbes S.C., Willcocks R.J., Lott D.J., DeVos S., Pollaro J., Rooney W.D., Sweeney H.L., Bonnemann C.G., Wang D.J., Vandenborne K., Walter G.A. Chemical shift-based MRI to measure fat fractions in dystrophic skeletal muscle. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:8–19. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Araujo E.C., Fromes Y., Carlier P.G. New insights on human skeletal muscle tissue compartments revealed by in vivo t2 NMR relaxometry. Biophys J. 2014;106:2267–2274. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saab G., Thompson R.T., Marsh G.D. Effects of exercise on muscle transverse relaxation determined by MR imaging and in vivo relaxometry. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;88:226–233. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graham S.J., Stanchev P.L., Bronskill M.J. Criteria for analysis of multicomponent tissue T2 relaxation data. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:370–378. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye F., Baligand C., Keener J.E., Vohra R., Lim W., Ruhella A., Bose P., Daniels M., Walter G.A., Thompson F., Vandenborne K. Hindlimb muscle morphology and function in a new atrophy model combining spinal cord injury and cast immobilization. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:227–235. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forbes S.C., Willcocks R.J., Triplett W.T., Rooney W.D., Lott D.J., Wang D.J., Pollaro J., Senesac C.R., Daniels M.J., Finkel R.S., Russman B.S., Byrne B.J., Finanger E.L., Tennekoon G.I., Walter G.A., Sweeney H.L., Vandenborne K. Magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy assessment of lower extremity skeletal muscles in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a multicenter cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Majumdar S., Kotecha M., Triplett W., Epel B., Halpern H. A DTI study to probe tumor microstructure and its connection with hypoxia. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014;2014:738–741. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2014.6943696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manning W.J., Wei J.Y., Katz S.E., Litwin S.E., Douglas P.S. In vivo assessment of LV mass in mice using high-frequency cardiac ultrasound: necropsy validation. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1672–H1675. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stuckey D.J., Carr C.A., Tyler D.J., Aasum E., Clarke K. Novel MRI method to detect altered left ventricular ejection and filling patterns in rodent models of disease. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:582–587. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lefaucheur J.P., Pastoret C., Sebille A. Phenotype of dystrophinopathy in old mdx mice. Anat Rec. 1995;242:70–76. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092420109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flanigan K.M., Ceco E., Lamar K.M., Kaminoh Y., Dunn D.M., Mendell J.R., King W.M., Pestronk A., Florence J.M., Mathews K.D., Finkel R.S., Swoboda K.J., Gappmaier E., Howard M.T., Day J.W., McDonald C., McNally E.M., Weiss R.B., United Dystrophinopathy Project LTBP4 genotype predicts age of ambulatory loss in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:481–488. doi: 10.1002/ana.23819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heydemann A., Ceco E., Lim J.E., Hadhazy M., Ryder P., Moran J.L., Beier D.R., Palmer A.A., McNally E.M. Latent TGF-beta-binding protein 4 modifies muscular dystrophy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3703–3712. doi: 10.1172/JCI39845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neumann P.E., Collins R.L. Genetic dissection of susceptibility to audiogenic seizures in inbred mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5408–5412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Libby R.T., Anderson M.G., Pang I.H., Robinson Z.H., Savinova O.V., Cosma I.M., Snow A., Wilson L.A., Smith R.S., Clark A.F., John S.W. Inherited glaucoma in DBA/2J mice: pertinent disease features for studying the neurodegeneration. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:637–648. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang J., Zhang G., Morrison B., Mori S., Sheikh K.A. Magnetic resonance imaging of mouse skeletal muscle to measure denervation atrophy. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:448–457. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stedman H.H., Sweeney H.L., Shrager J.B., Maguire H.C., Panettieri R.A., Petrof B., Narusawa M., Leferovich J.M., Sladky J.T., Kelly A.M. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature. 1991;352:536–539. doi: 10.1038/352536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Jong S., Zwanenburg J.J., Visser F., der Nagel R., van Rijen H.V., Vos M.A., de Bakker J.M., Luijten P.R. Direct detection of myocardial fibrosis by MRI. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:974–979. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park J., Wicki J., Knoblaugh S.E., Chamberlain J.S., Lee D. Multi-parametric MRI at 14T for muscular dystrophy mice treated with AAV vector-mediated gene therapy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McMillan A.B., Shi D., Pratt S.J., Lovering R.M. Diffusion tensor MRI to assess damage in healthy and dystrophic skeletal muscle after lengthening contractions. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:970726. doi: 10.1155/2011/970726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heemskerk A.M., Strijkers G.J., Vilanova A., Drost M.R., Nicolay K. Determination of mouse skeletal muscle architecture using three-dimensional diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1333–1340. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Donkelaar C.C., Kretzers L.J., Bovendeerd P.H., Lataster L.M., Nicolay K., Janssen J.D., Drost M.R. Diffusion tensor imaging in biomechanical studies of skeletal muscle function. J Anat. 1999;194(Pt 1):79–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19410079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Doorn A., Bovendeerd P.H., Nicolay K., Drost M.R., Janssen J.D. Determination of muscle fibre orientation using diffusion-weighted MRI. Eur J Morphol. 1996;34:5–10. doi: 10.1076/ejom.34.1.5.13156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tseng W.Y., Wedeen V.J., Reese T.G., Smith R.N., Halpern E.F. Diffusion tensor MRI of myocardial fibers and sheets: correspondence with visible cut-face texture. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17:31–42. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Damon B.M., Ding Z., Anderson A.W., Freyer A.S., Gore J.C. Validation of diffusion tensor MRI-based muscle fiber tracking. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48:97–104. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cleveland G.G., Chang D.C., Hazlewood C.F., Rorschach H.E. Nuclear magnetic resonance measurement of skeletal muscle: anisotrophy of the diffusion coefficient of the intracellular water. Biophys J. 1976;16:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(76)85754-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Galban C.J., Maderwald S., Uffmann K., de Greiff A., Ladd M.E. Diffusive sensitivity to muscle architecture: a magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging study of the human calf. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;93:253–262. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hall M.G., Clark C.A. Diffusion in hierarchical systems: a simulation study in models of healthy and diseased muscle tissue. Magn Reson Med. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26469. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1002/mrm.26469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li W., Liu W., Zhong J., Yu X. Early manifestation of alteration in cardiac function in dystrophin deficient mdx mouse using 3D CMR tagging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]