Abstract

The thyromimetic agent GC-1 induces hepatocyte proliferation via Wnt/β-catenin signaling and may promote regeneration in both acute and chronic liver insufficiencies. However, β-catenin activation due to mutations in CTNNB1 is seen in a subset of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC). Thus, it is critical to address any effect of GC-1 on HCC growth and development before its use can be advocated to stimulate regeneration in chronic liver diseases. In this study, we first examined the effect of GC-1 on β-catenin–T cell factor 4 activity in HCC cell lines harboring wild-type or mutated-CTNNB1. Next, we assessed the effect of GC-1 on HCC in FVB mice generated by hydrodynamic tail vein injection of hMet-S45Y-β-catenin, using the sleeping beauty transposon-transposase. Four weeks following injection, mice were fed 5 mg/kg GC-1 or basal diet for 10 or 21 days. GC-1 treatment showed no effect on β-catenin–T cell factor 4 activity in HCC cells, irrespective of CTNNB1 mutations. Treatment with GC-1 for 10 or 21 days led to a significant reduction in tumor burden, associated with decreased tumor cell proliferation and dramatic decreases in phospho-(p-)Met (Y1234/1235), p–extracellular signal-related kinase, and p-STAT3 without affecting β-catenin and its downstream targets. GC-1 exerts a notable antitumoral effect on hMet-S45Y-β-catenin HCC by inactivating Met signaling. GC-1 does not promote β-catenin activation in HCC. Thus, GC-1 may be safe for use in inducing regeneration during chronic hepatic insufficiency.

Thyroid hormone 3,3′-5-triiodo-l-thyronine (T3) is a strong regulator of multiple physiological processes, including cellular metabolic rate, embryonic development, and cell differentiation and proliferation.1 In particular, T3 is a potent mitogen in mouse and rat liver, and increases liver regeneration following surgical hepatectomy and hence may be a useful agent to induce regeneration.2 However, the use of T3 is hampered by its several side effects, such as increased heart rate, atrial arrhythmia, and muscle wasting.3, 4 Thus, many efforts have been made to design T3 analogs devoid of the toxic effects of T3 that could be used in the therapy of liver-related disease. In this scenario, the thyromimetic GC-1 (sobetirome) may be a promising option. In fact, although GC-1 mostly accumulates in the liver, its uptake is low in other tissues including heart, thus avoiding the cardiac collateral effects.5 Previous studies have shown that hepatocyte proliferation induced by T3/GC-1 is mostly due to their interaction with the thyroid hormone receptor β (THRβ), although the mechanisms driving cell proliferation are still unclear.6 A recent publication by Fanti et al7 demonstrates how β-catenin is crucial for this process. Indeed, T3 was unable to stimulate hepatocyte proliferation in mice knocked out for β-catenin. Moreover, it was also shown that T3 induces the activation of the protein kinase A (PKA), resulting in the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser675. As a consequence, P-Ser675-β-catenin is able to translocate into the nucleus where it activates the transcription of downstream genes involved in cell proliferation, such as cyclin-D1. Intriguingly, a follow-up study using conditional knockout mice for Wnt coreceptors LRP5-6, also showed dampened hepatocyte proliferative response to GC-1 and T3, which suggests that these thyromimetics induce hepatocyte proliferation at least in part through activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling as well.2

β-Catenin is the key effector of the Wnt pathway and mutations in Wnt genes or components of the signaling lead to developmental defects and cancer.8 Furthermore, previous studies showed that β-catenin activation in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is due to point mutations at the exon 3 of β-catenin gene (CTNNB1) that affect specific serine (S45Y) and threonine residues, which results in an aberrant activation of β-catenin in a subset of human HCCs.9 Interestingly, a concomitant HMET overexpression or activation, together with CTNNB1 mutations, was found in 9% to 12.5% of patients with HCC.10 Moreover, by using the sleeping beauty transposon/transposase (SBTT) and hydrodynamic tail vein injection (HTVI), the coexpression of hMet and mutant-β-catenin (S45Y-β-catenin) led to HCC in mice, indicating that this animal model recapitulates the conditions characterizing a subset of human HCC. Follow up studies showed that Ras activation downstream of Met may be the predominant mechanism of HCC in this model because coexpression of mutant Ras and mutant β-catenin led to HCC development with >90% molecular similarity to hMet-β-catenin HCC.11 Furthermore, suppression of β-catenin led to a notable decrease in HCC burden, suggesting the importance of β-catenin in tumor growth and progression in this model.

Because GC-1 may be of relevance as regenerative therapy both in transplantation settings and in chronic liver diseases, it is pertinent to directly address its effects on tumor growth and development, especially those that are driven by the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. The current study was devised to specifically assess the effect of GC-1 on liver tumor cells and in a HCC model driven by the coexpression of S45Y-β-catenin and hMet using SBTT and HTVI.10 We demonstrate that GC-1 actually decreases tumor burden owing to decreased tumor cell proliferation with a notable decrease in Met–extracellular signal-related kinase (Erk) and Met-Stat3 signaling and no effect on Akt or Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Thus, GC-1 suppresses tumorigenesis and, more importantly, does not enhance Wnt/β-catenin in HCC, demonstrating its overall safety for use in chronic liver diseases to induce regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Animals, Plasmids, and Hydrodynamic Tail Vein Injections

SBTT plasmids and HTVI have been described previously.10 Briefly, 20 μg of a pT3-EF5α-hMet-V5 and pT3-EF5α-S45Y-β-catenin-Myc combination along with the transposase in a ratio of 25:1 were diluted in 2 mL of normal saline (0.9% NaCl), filtered through a 0.22-μm filter (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), and injected into the lateral tail vein of 23 FVB mice that were around 6 weeks old, in 5 to 7 seconds. These mice are referred henceforth as hMet-mutant-β-catenin mice. Four weeks after injection, hMet-mutant-β-catenin mice were randomized into two groups. One group was kept on a basal diet (n = 12), and another group was switched to a GC-1–supplemented diet (5 mg/kg of diet; Medchem Express, Monmouth Junction, NJ) (n = 11). Animals on control diet were sacrificed at either 21 days (n = 8) or 10 days (n = 4) after initiation of the diet. Similarly, animals on the GC-1 diet were sacrificed at either 21 days (n = 7) or 10 days (n = 4) after initiation of the diet. The animals were given access to food and water ad libitum with a 12-hour light/dark daily cycle. One intraperitoneal injection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was performed on day 9 during 10 days of GC-1 or basal diet treatment, and livers were harvested 24 hours later. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals12 was followed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Pittsburgh.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Four-micrometer formalin-fixed sections were deparaffinized in graded xylene and alcohol, and rinsed in PBS. To block endogenous peroxidase activity, the sections were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). For antigen retrieval, slides were microwaved in citrate buffer followed by blocking with Superblock (ScyTek Laboratories, Logan, UT) for 10 minutes. Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C or 1 hour room temperature in the following antibodies: cyclin-D1 (Thermo-Scientific, Fremont, CA), Glutamine synthetase, Ki-67, Myc-tag, and CD45 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX). Sections were then incubated with species-specific secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature. Sections stained with antibodies were incubated with streptavidin-biotin, and signal was detected with diaminobenzidine (DAB). Cell death was evaluated in liver sections by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) using manufacturer's instructions available with the kit (EMD-Millipore). BrdU was stained with mouse antibody (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as previously described.2 Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized, exposed to 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in deionized water for 10 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase, treated with 2 N HCl, and incubated with trypsin 0.1% for 20 minutes and then with normal goat serum for 20 minutes at room temperature. Sections were then incubated overnight in a cold room with anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody, followed by biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG. DAB kit was then applied, and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

For quantification of Ki-67 IHC, pictures were taken at 200× magnification from either tumor or nontumor areas in the same slide. Each picture was separated into DAB staining channel and hematoxylin staining channel by Color Deconvolution using ImageJ2 Fiji (http://imagej.net/ImageJ2).13, 14 To quantify the number of Ki-67–positive nuclei on each picture, the DAB staining on the DAB channel was highlighted with the threshold of 48 and then quantified with Analyze Particles. All particles of areas smaller than 100 pixels were excluded. To quantify the total number of nuclei on each picture, the hematoxylin staining on the hematoxylin channel was highlighted with the threshold of 205 and then quantified with Analyze Particles with similar exclusion of small areas. The percentage of Ki-67–positive nuclei on each picture was calculated by dividing the number of particles counted from the DAB channel by the number of particles counted from the hematoxylin channel.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Flash-frozen livers from hMet-mutant-β-catenin FVB mice on control/basal diet or GC-1 diet were used to obtain whole-cell lysates. For protein extraction, a small amount of liver tissue was homogenized using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing the protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Tissue homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 5 minutes in cold room. Supernatant was recovered and stored at −80°C for use. Aliquots of 30 to 50 μg of proteins were denatured by boiling in Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Life Technologies) using the Bio-Rad transfer apparatus. Membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk or 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 hour. Western blot (WB) analysis was performed using the following primary antibodies: Active β-catenin (dilution 1:800; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), cyclin-D1 (dilution 1:1000; Thermo-Scientific), glutamine synthetase (GS) (dilution 1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), ERK1/2 (dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling), phospho-(p-)ERK1/2 (T202, Y204) (dilution 1:1000; Cell Signaling), p-Met (Y1234/1235) (1; dilution 1:500; CST 3077S; Cell Signaling), p-Met (Y1234/1235) (2; dilution 1:500; CST 3129S; Cell Signaling), total Met (dilution 1:500; Cell Signaling), STAT3 (dilution 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-STAT3 (Y705) (dilution 1:100; Cell Signaling), AKT (dilution 1:1000, Cell Signaling), and p-AKT (S475) (dilution 1:1000; Cell Signaling). Membranes were incubated in primary antibodies and diluted in 5% skim milk or 5% bovine serum albumin following overnight incubation at 4°C. Membranes were then incubated with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody horseradish peroxidase–conjugated IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were detected by Super-Signal West Pico Chemiluminescense Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and revealed by autoradiography.

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), from frozen liver tissue. Aliquots containing 2 μg of total RNA were reverse-transcribed after DNase enzymatic treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination, using Super Script III first strand kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Deiodinase 1 values were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

TopFlash Reporter Assay

Three liver tumor cell lines, Hep3B, HepG2, and Snu-398 cells, were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were transfected simultaneously with Renilla reniformis luciferase (pRL-TK; Promega, Madison, WI) as a transfection control and TopFlash firefly luciferase plasmids (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), which contains three copies of the Tcf/Lef sites upstream of a thymidine kinase promoter and the firefly luciferase gene using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 5 to 7 μmol/L GC-1 (Medchem Express) for 24 hours. Lysates were harvested using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Firefly luciferase signals were normalized to Renilla luciferase and the ratio between groups compared by t-test to determine significance. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Statistical Analysis

All statistics were performed using the Prism 6 software version 6 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA), and the comparison between treated and control groups was performed by t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

GC-1 Treatment Does Not Enhance β-catenin–TCF4 Reporter Activity in CTNNB1-Mutated and Nonmutated Human HCC Cells

GC-1 has been found to stimulate hepatocyte proliferation at least in part through the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.2, 7 Because Wnt/β-catenin activation due to mutations in key effectors of the pathway is reported in a significant subset of HCC cases, it is relevant to address whether GC-1 can promote β-catenin–T cell factor 4 (TCF4) activity in various liver tumor cells before its use in inducing liver regeneration in chronic liver diseases is considered. Here, the effect of GC-1 treatment on three different liver tumor cell lines that normally contain wild-type CTNNB1 (Hep3B cells), point-mutant β-catenin (Snu-398 cells), and exon 3–deletion mutant of CTNNB1 (HepG2 cells) were directly examined. TopFlash reporter–transfected cells were treated for GC-1 as indicated in Materials and Methods. GC-1 treatment had no significant effect on the TopFlash luciferase reporter activity in any of the three cell lines as compared to the respective DMSO-treated controls (Figure 1). Thus, irrespective of the status of β-catenin gene mutations, GC-1 does not increase or decrease Wnt/β-catenin activity in various HCC cell lines.

Figure 1.

GC-1 does not influence β-catenin–T cell factor 4 activity as evident by TopFlash reporter assay in liver tumor cell lines. Bar graph shows insignificant differences in TopFlash luciferase reporter activity in Hep3B cells (with wild-type CTNNB1 gene) (A), Snu-389 cells (have exon-3 point-mutant CTNNB1 gene) (C), and HepG2 cells (have exon-3 deletion–mutant CTNNB1 gene) (E) treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 7 μmol/L GC-1. Each well for the treatment groups is indicated by a closed circle (DMSO) or closed square (GC-1). Lack of TopFlash reporter response to GC-1 in Hep3B (B), Snu-398 (D), and HepG2 (F) cells is depicted as fold-change to DMSO treatment.

Three-Week Treatment with GC-1 Decreases Tumor Burden in hMet-S45Y-β-Catenin HCC Model by Decreasing Tumor Cell Proliferation

To further address any effect of GC-1 on HCC in vivo in a model that represents a clinical disease, and is driven by combination of two proto-oncogenes—mutant-CTNNB1 and hMet—a recently described murine model was used.10 hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice were randomized into two groups, one received basal and another GC-1 diet for 21 days as described in Materials and Methods (Figure 2A). Effectiveness of GC-1 was verified by examining hepatic expression of deiodinase 1 (Dio1) gene, a surrogate target of THRβ,12, 13, 14, 15, 16 which was significantly up-regulated in GC-1–treated group by RT-PCR (Figure 2B). GC-1's effect on overall tumor burden was next assessed by comparing the liver weight to body weight ratios (LW/BW × 100; percent) in the two groups. An almost significant decrease (P = 0.0506) in LW/BW was evident in the GC-1 group (Figure 2C). Grossly, most livers from basal diet group showed large tumors and an irregular surface depicting notable tumorigenesis, whereas all livers from GC-1–treated groups showed a relatively smooth surface and smaller nodules (Figure 2D). hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of livers from basal diet–fed mice after 7 weeks of HTVI showed several abutting tumor foci with only a few layers of normal hepatocytes compressed in between (Figure 3A). This was clearly evident in immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Myc-tag in these liver sections (Figure 3B), as also shown previously.10 The GC-1 diet–fed hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice showed notably smaller tumor nodules interspersed among normal hepatocytes as seen by both H&E and Myc-tag IHC (Figure 3, A and B). A modest decrease in Myc-tag levels by WB analysis also verified an overall lower tumor burden in this group of animals (Figure 3C).

Figure 2.

hMet-mutant-β-catenin–injected mice fed a GC-1 diet for 3 weeks, develop lesser hepatocellular carcinomas than controls. A: Schematic showing the timing of GC-1 or basal diet administration and animal sacrifice in reference to the hydrodynamic tail vein injection of sleeping beauty transposon/transposase plasmids. B: RT-PCR using RNA isolated from livers shows around 40-fold increase in gene expression of deiodinase (DIOI) after 21 days of the GC-1 diet as compared to the basal diet. C: An almost significant (P = 0.0506) difference in liver weight/body weight (LW/BW × 100) is observed after 21 days of the GC-1 diet as compared to the basal diet, suggesting a decrease in tumor burden. Individual animals in each group are indicated by a closed circle or closed square. D: Representative gross liver images from 21 days of GC-1 diet–fed versus basal diet–fed animals show lesser nodularity and tumor burden in the GC-1 group. n = 7 (C, GC-1 diet); n = 8 (C, basal diet). ***P < 0.001 versus the basal diet.

Figure 3.

Decreased tumor size in hMet-mutant-β-catenin model following 21 days of GC-1 reflected by histology and reduced Myc-tag, without any change in cell death. A: Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections show relatively fewer and smaller microscopic hepatic tumor nodules in GC-1–treated group at 21 days. B: Representative immunohistochemically stained image for Myc-tag shows smaller hepatic tumor nodules at 21 days of GC-1 treatment versus controls. C: Representative Western blot shows a modest decrease in overall levels of Myc-tag, which supports an overall lower tumor burden after 21 days of GC-1 treatment. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) shows comparable loading. D: A modestly higher number of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)–positive nuclei within the tumor foci were evident in the control diet–fed group versus GC-1 diet–fed mice, likely due to larger size of tumor nodules. Original magnification: ×50 (A, B, and D).

To address the basis of smaller tumor foci in hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice after GC-1 versus control diet, TUNEL was first performed as a marker of cell death. More TUNEL-positive cells were evident in the basal diet group as compared to the GC-1 group, likely due to excessive tumor size, precluding increased cell death to be the mechanism of lower tumor burden (Figure 3D).

Next, IHC for Ki-67, a marker of cells in S-phase of cell cycle, was performed. Although tumor nodules were smaller in the liver sections of the GC-1–treated group, several cells were positive for Ki-67 staining within the tumor nodules as compared to the basal diet, where relatively fewer tumor cells within large nodules were positive (Figure 4A). Quantification of Ki-67 IHC revealed insignificant differences in the percentage of positive tumor cells within nodules between the two groups (Figure 4B). Likewise, nontumor areas of both groups showed scant KI-67–positive cells, and differences between GC-1 and basal diet group were insignificant (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Continued proliferation in smaller tumor nodules following 21 days of GC-1 treatment as shown by numbers of cells in S-phase. A: Scattered Ki-67–positive cells in large tumor nodules in liver sections of basal diet–fed mice. Although tumor nodules are smaller in the GC-1–treated group, several cells continue to be Ki-67 positive within tumor foci. B: Quantification of Ki-67 staining shows a comparable percentage of Ki-67–positive tumor cells within foci in the control diet and GC-1 diet–fed mice. Nontumor tissues in both groups also show insignificant differences in Ki-67 positivity. Each color represents counts from one animal. Original magnification, ×50 (A).

Three-Week Treatment with GC-1 in hMet-S45Y-β-Catenin HCC Model Does Not Impact Wnt Signaling

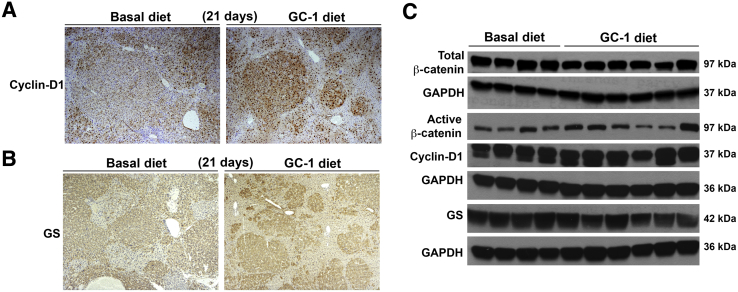

To address the molecular basis of reduced tumor burden, whether GC-1 could have any paradoxical and negative effect on Wnt signaling pathway was first assessed because it is known to promote Wnt signaling in the context of cell proliferation and liver regeneration.2, 7 The status of tumor nodules in each group was first examined for Wnt/β-catenin pathway targets such as cyclin-D1 and GS by IHC. Tumor nodules in the basal diet group were strongly positive for cyclin-D1 as were the nodules in the GC-1 diet group, despite being smaller in the latter group (Figure 5A). Cyclin-D1 was localized to both tumors as well as the surrounding normal tissue in both groups. The tumors were uniformly and comparably positive for GS by IHC in both groups despite the smaller size of nodules in the GC-1 group (Figure 5B). GS was localized mostly in the tumors in both groups.

Figure 5.

β-Catenin signaling in tumor-bearing livers remains unaffected after 21 days of GC-1 treatment. A: A representative section from the liver of hMet-β-catenin mice fed 21 days with GC-1 or basal diet and stained for cyclin-D1 shows comparably positive staining although the tumor foci are smaller after GC-1 treatment. B: A representative immunohisctochemically stained image for glutamine synthetase (GS) shows GS-positive tumor nodules in both the GC-1 and the basal diet groups, although, the foci are notably smaller in GC-1 group. C: No change in levels of total β-catenin, active-β-catenin, or cyclin-D1, and a marginal decrease in total GS levels by representative Western blot, following 21 days of GC-1 treatment, suggests no change in Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) shows comparable loading. Original magnification: ×50 (A and B).

To validate IHC findings, WB analysis was performed on lysates from tumor-bearing livers from both groups for Wnt signaling components. Total and active β-catenin levels remained unaltered in the two groups (Figure 5C). Similarly, no change in cyclin-D1 levels were evident by WB (Figure 5C). A modest decrease in GS levels by WB in the GC-1 group may also represent a decrease in tumor burden because, like Myc-tag, GS was predominantly expressed in tumor nodules only (Figure 5C).

Thus, GC-1 had no impact on Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice and more importantly did not increase this signaling pathway or promote HCC burden.

Three-Week Treatment with GC-1 in hMet-S45Y-β-Catenin HCC Model Impairs Met-Erk and Met-Stat3 Signaling

Because HCC in the hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice is due to functional and synergistic cooperation of the two proto-oncogenes,10 and because GC-1 did not alter Wnt signaling, its effect on Met signaling was tested. A dramatic decrease in p-Met (Tyr 1234/1235) was observed in the GC-1–treated group as compared to the basal diet controls (Figure 6A). Total Met levels were only marginally and variably decreased after GC-1 treatment (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

GC-1 treatment of hMet-mutant-β-catenin mice for 21 days leads to marked inhibition of Met signaling. A: A profound decrease in p-Met (Y1234/Y1235) is observed by Western blot (WB) analysis using whole-liver lysates from GC-1–treated mice versus basal diet controls. A marginal, but variable, decrease in total Met is also evident in this group. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) shows comparable loading. B: Another representative WB shows lack of p-Met (Y1234/1235) along with a dramatic decrease in downstream p-ERK1 (T202) and p-ERK2 (Y204) in GC-1–treated liver lysates. Total ERK1/2 levels are modestly decreased as well. GAPDH shows comparable loading. C: A representative WB shows no change in p-AKT levels, whereas total AKT levels are marginally increased after GC-1 treatment. However, although total STAT3 levels are relatively unaltered, a notable decrease in p-STAT3 (Y705) is clearly noticeable after 21 days of GC-1 treatment. GAPDH verified comparable protein loading.

Because Met signaling was recently shown to predominantly act through downstream Ras-Erk signaling, and cooperate with mutant-β-catenin in the development of HCC,11 the levels of both total and p-ERK were assessed. Both total and p-ERK1 and total and p-ERK2 were notably decreased following GC-1 treatment (Figure 6B). p-AKT levels showed comparable levels in the two groups (Figure 6C). There was however, a striking decrease in p-STAT3 levels following GC-1 treatment (Figure 6C).

Thus GC-1 treatment led to a notable decrease in Met-ERK and Met-Stat3 signaling to affect overall tumor burden in the hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice.

Ten-Day Treatment with GC-1 Decreases Tumor Burden in hMet-S45Y-β-Catenin HCC Model by Decreasing Tumor Cell Proliferation

To further validate the mechanism of GC-1 on tumorigenesis in the hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mouse model of HCC, a short-term GC-1 treatment was performed as described in Materials and Methods (Figure 7A). Hepatic expression of Dio1 was significantly increased in the 10-day GC-1 group versus control group (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

hMet-mutant-β-catenin–injected mice fed a GC-1 diet for 10 days show significantly fewer tumors than controls. A: Schematic showing the timing of GC-1 or basal diet administration and animal sacrifice in reference to the hydrodynamic tail vein injection of sleeping beauty transposon/transposase plasmids. B: RT-PCR using RNA isolated from livers shows around 10-fold increase in gene expression of deiodinase (DIOI) after 10 days of the GC-1 diet as compared to the basal diet. C: A significant difference in liver weight/body weight (LW/BW × 100) is observed after 10 days of the GC-1 diet as compared to the basal diet suggesting a decrease in tumor burden. Individual animals in each group are indicated by a closed circle or closed square. D: Representative gross liver images from 10 days of GC-1– versus basal diet–fed animals show unremarkable differences in the two groups. n = 4 (C, GC-1 diet and basal diet). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus the basal diet.

To address the effect of GC-1 on tumor burden, LW/BW between the two groups was next compared. A significant decrease (P = 0.0022) in LW/BW was evident after GC-1 treatment (Figure 7C). Grossly, the livers from the basal diet and GC-1 diet groups looked indistinguishable and without gross tumor nodules (Figure 7D). H&E staining of liver sections showed several small, well-differentiated tumor foci composed of cells with basophilic cytoplasm and some nuclear atypia (Figure 8A). Staining for Myc-tag confirmed the presence of several tumor foci spread throughout liver sections (Figure 8A). Smaller and fewer tumor foci were apparent in the GC-1 diet–fed group as observed by H&E and Myc-tag staining, although histological features of tumors were not altered (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Decreased tumor volume in hMet-mutant-β-catenin model following 10 days of the GC-1 diet is not due to altered cell survival or inflammation. A: Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections show relatively fewer and smaller microscopic tumor foci evident as nodules composed of cells with basophilia, pyknotic nuclei, and greater nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, in the 10-day GC-1 diet–fed group versus the basal diet group. Immunohistochemically stained image for Myc-Tag for the 10-day GC-1–treated group versus controls also shows smaller and fewer tumor foci. B: Comparable terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)–positive nuclei within the tumor foci are evident in the 10-day control diet–fed group versus the GC-1 diet–fed mice. C: Comparable numbers of CD45-positive inflammatory cells are seen in both the basal diet and the GC-1 diet groups. Original magnification: ×50 (A and B); ×100 (C).

To address the basis of reduced tumor burden, the livers from both groups were compared for TUNEL. Comparable numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were evident between the two groups (Figure 8B). No differences in the number of CD45-positive between the two groups were observed, suggesting that intra- and extratumoral inflammation is unaffected by GC-1 (Figure 8C).

Effect of 10-day treatment of GC-1 on cell proliferation was assessed by IHC for BrdU and Ki-67. A notable decrease in both markers was evident within the tumor foci in the GC-1–treated group (Figure 9, A and B). Quantification revealed a significant decrease in the percentage of Ki-67–positive cells within tumor nodules after GC-1 treatment (Figure 9C). No differences in Ki-67–positive cell numbers were observed in nontumor areas between the basal and GC diet groups (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

Decreased tumor volume in hMet-mutant-β-catenin model following 10 days of GC-1 diet is due to lower tumor cell proliferation. A: Immunohistochemically stained image for BrdU shows a dramatic decrease in the numbers of BrdU-positive cells after 10 days of GC-1 feeding as compared to controls. B: A notable decrease in the numbers of Ki-67–positive cells within tumor nodules is evident in the GC1-treated group versus controls. C: Quantification of Ki-67 staining shows a highly significant decrease in percentage of Ki-67–positive tumor cells in tumor foci in the 10-day GC-1 diet–fed mice as compared to the basal diet group. Nontumor tissues in both groups show insignificant differences in Ki-67 positivity. Each color represents counts from one animal. **P < 0.01, versus the basal diet. Original magnification: ×50 (A and B).

Ten-Day Treatment with GC-1 in hMet-S45Y-β-Catenin HCC Model Does Not Impact Wnt Signaling

To investigate whether there was any effect of short-term GC-1 treatment on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, IHC was performed for cyclin-D1 and GS. Tumor nodules in basal diet group were strongly and uniformly positive for cyclin-D1, as well as for GS (Figure 10, A and B). After GC-1 treatment for 10 days, tumors continued to be positive for cyclin-D1, as well as for GS, although a notable diminution in number and size of tumor foci was visible (Figure 10, A and B). Both GS and cyclin-D1 were predominantly localized in the tumor foci.

Figure 10.

Ten days of GC-1 treatment does not impact Wnt signaling despite lowering tumor burden. A: Representative sections from the livers of hMet-β-catenin mice fed 10 days with a GC-1 or basal diet and stained for cyclin-D1 show comparably positive staining within tumor foci although the tumor foci are smaller in the GC-1 group. B: Representative immunohistochemically stained image for glutamine synthetase (GS) also shows GS-positive tumor nodules in both the GC-1 and basal diet groups, although the foci are notably smaller in the GC-1 group. C: Representative Western blot analysis shows a marginal decrease in overall levels of total β-catenin, cyclin-D1, and GS, but not active β-catenin, all supporting an overall lower tumor burden after 10 days of GC-1 treatment, but not a direct impact on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) shows comparable loading. Original magnification: ×50 (A and B).

Protein expression of total and active β-catenin was investigated along with cyclin-D1 and GS levels by WB using the liver lysates from both groups. A modest decrease in the levels of total, but not active, β-catenin were observed in the 10-day GC-1 diet groups (Figure 10C). Similarly, marginal decreases in cyclin-D1 and modest decreases in GS levels by WB were evident in the GC-1 group (Figure 10C).

IHC and WB results together suggest that the seeming reduction in the Wnt signaling following GC-1 may be actually be the result of and not the cause of overall decreased tumor burden, because cyclin-D1 and GS continued to be mostly expressed in the tumor foci in both control and treatment groups. Thus, short-term GC-1 treatment also did not impact Wnt/β-catenin signaling and more importantly, did not induce it to promote HCC burden.

Ten-Day Treatment with GC-1 in hMet-S45Y-β-Catenin HCC Model Impairs Met-Erk and Met-Stat3 Signaling

Eventually, to further validate the impact on Met-Erk and Met-Stat3 signaling, liver lysates from the 10-day GC-1–treated or control group were assessed. Total Met levels were modestly decreased after GC-1 treatment (Figure 11A). A profound decrease by in p-Met (Tyr 1234/1235) was observed in the GC-1–treated group and validated by two independent antibodies (Figure 11B). Likewise, although total ERK levels were unaffected, both p-ERK1 and p-ERK2 were dramatically decreased following GC-1 treatment as compared to the controls (Figure 11B). GC-1 treatment did not have any effect on p-AKT levels; however, a profound decrease in p-STAT3 was clearly evident (Figure 11C).

Figure 11.

Remarkable decrease in Met-ERK and Met-STAT3 signaling following 10 days of GC-1 treatment in hMet-mutant-β-catenin mice. A: A pronounced decrease in p-Met (Y1234/Y1235) is observed and validated by two independent antibodies by Western blot (WB) analysis using whole-liver lysates from 10-day GC-1–treated versus basal diet–fed hMet-mutant-β-catenin mice. A marginal decrease in total Met levels is evident in this group as well. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) shows comparable loading. B: A representative WB using total liver lysates shows a dramatic decrease in p-ERK1 (T202) and p-ERK2 (Y204), but not total ERK after 10 days of GC-1. GAPDH shows comparable loading. C: A representative WB shows no change in total AKT or p-AKT levels after 10 days of GC-1 treatment. Total STAT3 levels are overall reduced, whereas p-STAT3 (Y705) levels are drastically lower after 10 days of GC-1 treatment. GAPDH verified comparable protein loading.

Thus, GC-1 affects Met-ERK and Met-Stat signaling to reduce tumor burden in the hMet-S45Y-β-catenin mice.

Discussion

There is a major unmet clinical need in the area of hepatic regenerative medicine because there are limited options for acute or chronic hepatic insufficiency, which will ultimately progress to end-stage liver disease. Treatment of end-stage liver disease is often liver transplantation; however, a shortage of organs for transplantation necessitates further research to seek alternatives.17 Current research is focused on innovations in transplantation procedures, generation of de novo organs, cell therapy, stem cell differentiation, and bioartificial livers.18 Another strategy is to stimulate liver regeneration to promote functional hepatocyte mass within a diseased liver.19 Such regenerative therapy could have potential applicability in treatment of acute and chronic liver injuries, as well as in transplantation settings, including small-for-size and living donors. Thyromimetics such as T3 or THRβ agonists such as GC-1 or sobetirome have shown their relevance as regenerative therapies in several preclinical studies.2, 6, 7, 20, 21 T3 and GC-1 induce cell proliferation through up-regulation of cyclin-D1,22, 23 which in the liver, depends on Wnt/β-catenin signaling and PKA-dependent β-catenin activation.2, 7 Also, β-catenin signaling is normally activated during regeneration after acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury or after partial hepatectomy, and β-catenin stabilization itself promotes liver regeneration.24, 25, 26, 27, 28 GC-1 pretreatment before partial hepatectomy accelerated cyclin-D1 expression after the surgery and led to an earlier transition of hepatocytes into S-phase during liver regeneration.2 These studies rationalize the use of thyromimetics, especially THRβ agonists with more selective action on hepatocytes,6 in inducing regeneration. However, the safety of these agents, especially their effect on hepatic tumor cell proliferation, needs to be directly investigated before their use in chronic hepatic injuries or preneoplastic conditions can be considered.

Chronic hepatic injuries may benefit from regenerative therapies to sustain and even expand the residual functional hepatocyte mass. However, chronic hepatic injuries such as viral hepatitis, nonalcoholic or alcoholic hepatitis, and others, often and over an extended time period lead to progressive fibrosis with regenerative nodules that maintain liver function and are often complicated by acute-on-chronic liver failure.29 As injury progresses and cirrhosis ensues, the risk for development of HCC also increases. Thus, for regenerative therapies to become a reality, it is pertinent to directly address their effect on HCC to especially demonstrate that they do not worsen the growth and development of hepatic tumors. This is particularly relevant for GC-1, which induces activation of β-catenin in normal liver to induce regeneration,2 and because β-catenin activation due to mutations in CTNNB1 is a common event in HCC.9

In vitro studies using three different cell lines with varying status of β-catenin gene mutations and associated Wnt/β-catenin activity, showed no effect of GC-1 on β-catenin–TCF4 activity. More importantly, GC-1 never increased TopFlash activity in any of the liver tumor lines irrespective of CTNNB1 mutational status. Although basal luciferase activity in the three cell lines used was commensurate with CTNNB1 mutational status, such that HepG2 cells (exon 3 deletion) had the highest, Snu-398 cells (missense mutation in exon 3) the next highest, and Hep3B cells (wild-type) the lowest, GC-1 treatment did not alter the respective basal β-catenin–TCF4 activity. It is important to note that T3 is known to increase TopFlash luciferase activity in primary hepatocytes.7 Why thyromimetics are unable to stimulate β-catenin activity in liver tumor cells but do so in normal hepatocytes is presently unknown, and future studies will be essential to discern such mechanisms.

To validate the lack of effect of GC-1 on β-catenin–TCF4 activity and to investigate any effect of GC-1 on tumor growth and development in vivo, a clinically relevant model that represents 10% of human HCC10 was used. Stable expression of mutant β-catenin and hMet in a subset of hepatocytes in mice leads to HCC, which is partially β-catenin–addicted.11 Administration of GC-1 for 10 or 21 days to these mice once tumors were established did not promote Wnt/β-catenin signaling in liver as shown by unaltered levels of total and active (hypophosphorylated) β-catenin along with its targets GS and cyclin-D1. In fact, no difference in the localization or intensity of cyclin-D1 or GS within existing tumor nodules was observed after GC-1 treatment as compared to the control-fed normal diet. This was in contrast to previously used lipid nanoparticles used to deliver siRNA against CTNNB1, which suppressed β-catenin expression, inhibited downstream signaling as demonstrated by the lack of GS and cyclin-D1 in tumor nodules, and dramatically inhibited tumor growth in a related HCC model.11 Thus, GC-1, similar to in vitro studies, did not alter and more importantly did not increase β-catenin activity in HCC in vivo in the hMet-β-catenin model (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Schematic of the disparate effect of GC-1 on β-catenin signaling in normal hepatocyte versus a liver tumor cell. Thyroid hormone receptor β agonist GC-1 induces β-catenin signaling in the normal hepatocyte by activating PKA-dependent ser675-phosphorylation (arrow) of β-catenin as well as by Wnt-dependent mechanisms (arrow). This leads to enhanced cyclin-D1 expression and hepatocyte proliferation, and may be applicable for regenerative therapies. However, in a tumor cell, GC-1 is unable to increase β-catenin activation (small diamond) irrespective of the CTNNB1 mutational status. In addition, it dramatically inhibits Met-ERK and Met-Stat3 phosphorylation to have a profound effect on tumor burden in hMet-mutant-β-catenin mice, which represents around 10% of all human HCC. Mut, mutated; p-, phospho-; WT, wild type.

Intriguingly however, despite the lack of effect on Wnt signaling, GC-1 treatment decreased overall HCC burden in this model. This was a desirable effect because theoretically, GC-1 use, not only could induce regeneration, but may affect tumorigenesis in chronic liver diseases (Figure 12). Indeed, despite its mitogenic capacity, T3 was previously shown to accelerate remodeling of chemically induced preneoplastic lesions in rats subjected to the resistant-hepatocyte model of hepatocarcinogenesis.30 Recently, GC-1 was shown to also negatively influence the carcinogenic process through an induction of a differentiation program within preneoplastic hepatocytes based on analysis of molecular markers.31 In our current study, we identified a heretofore unrecognized effect of GC-1 on inhibiting Met phosphorylation. Both at 10 days and 21 days, GC-1 treatment profoundly suppressed Met-phosphorylation while modestly decreasing total Met levels. Met phosphorylation and activation in hMet-β-catenin model are due to Met overexpression, which leads to activation of Met signaling via autophosphorylation at Y1234/1235. GC-1 seems to inhibit Met phosphorylation at these residues, which in turn impacts p-ERK1 and p-ERK2 as well as p-STAT3, without impacting P-AKT (Figure 12). The mechanism of how GC-1 leads to hypophosphorylation of Met remains under investigation. Because GC-1 can activate THRβ to induce both genomic and nongenomic downstream effects, further studies will need to specifically identify downstream effectors that may modulate Met signaling such as protein-tyrosine phosphatases as shown elsewhere.32

In conclusion, use of GC-1 in chronic liver diseases to induce regeneration may be safe and in fact be advantageous due to its observed tumor inhibitory effect. This feature makes GC-1 an attractive candidate both as regenerative and an anti-tumoral agent.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants R01DK62277, R01DK100287, R01DK095498, and R01CA204586 (S.P.M.); Endowed Chair for Experimental Pathology (S.P.M.); and Sardinian Regional Government Ph.D. fellowship P.O.R. Sardegna F.S.E. 2007-2013 (E.P.).

Disclosures: S.P.M. is a consultant for and has research agreements with Abbvie Pharmaceuticals and Dicerna Pharmaceuticals.

E.P. and Q.M. contributed equally to this work.

J.Y. and S.P.M. contributed equally as senior authors.

Contributor Information

Jinming Yu, Email: sdyujinming@163.com.

Satdarshan P. Monga, Email: smonga@pitt.edu.

References

- 1.Huang Y.H., Tsai M.M., Lin K.H. Thyroid hormone dependent regulation of target genes and their physiological significance. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarado T.F., Puliga E., Preziosi M., Poddar M., Singh S., Columbano A., Nejak-Bowen K., Monga S.P. Thyroid hormone receptor beta agonist induces beta-catenin-dependent hepatocyte proliferation in mice: implications in hepatic regeneration. Gene Expr. 2016;17:19–34. doi: 10.3727/105221616X691631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxi E.G., Schott J.T., Fairchild A.N., Kirby L.A., Karani R., Uapinyoying P., Pardo-Villamizar C., Rothstein J.R., Bergles D.E., Calabresi P.A. A selective thyroid hormone beta receptor agonist enhances human and rodent oligodendrocyte differentiation. Glia. 2014;62:1513–1529. doi: 10.1002/glia.22697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter J.D., Webb P. Thyroid hormone mimetics: potential applications in atherosclerosis, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:308–320. doi: 10.1038/nrd2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi H.C., Chen C.Y., Tsai M.M., Tsai C.Y., Lin K.H. Molecular functions of thyroid hormones and their clinical significance in liver-related diseases. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:601361. doi: 10.1155/2013/601361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Columbano A., Pibiri M., Deidda M., Cossu C., Scanlan T.S., Chiellini G., Muntoni S., Ledda-Columbano G.M. The thyroid hormone receptor-beta agonist GC-1 induces cell proliferation in rat liver and pancreas. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3211–3218. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fanti M., Singh S., Ledda-Columbano G.M., Columbano A., Monga S.P. Tri-iodothyronine induces hepatocyte proliferation by protein kinase A-dependent [beta]-catenin activation in rodents. Hepatology. 2014;59:2309–2320. doi: 10.1002/hep.26775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald B.T., Tamai K., He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monga S.P. [beta]-Catenin signaling and roles in liver homeostasis, injury, and tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1294–1310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao J., Xu E., Zhao Y., Singh S., Li X., Couchy G., Chen X., Zucman-Rossi J., Chikina M., Monga S.P. Modeling a human hepatocellular carcinoma subset in mice through coexpression of met and point-mutant [beta]-catenin. Hepatology. 2016;64:1587–1605. doi: 10.1002/hep.28601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tao J., Zhang R., Singh S., Poddar M., Xu E., Oertel M., Chen X., Ganesh S., Abrams M., Monga S.P. Targeting [beta]-catenin in hepatocellular cancers induced by coexpression of mutant [beta]-catenin and K-Ras in mice. Hepatology. 2017;65:1581–1599. doi: 10.1002/hep.28975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Research Council . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schindelin J., Rueden C.T., Hiner M.C., Eliceiri K.W. The ImageJ ecosystem: an open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2015;82:518–529. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bianco A.C., Kim B.W. Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2571–2579. doi: 10.1172/JCI29812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gullberg H., Rudling M., Salto C., Forrest D., Angelin B., Vennstrom B. Requirement for thyroid hormone receptor beta in T3 regulation of cholesterol metabolism in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1767–1777. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collin de l'Hortet A., Takeishi K., Guzman-Lepe J., Handa K., Matsubara K., Fukumitsu K., Dorko K., Presnell S.C., Yagi H., Soto-Gutierrez A. Liver-regenerative transplantation: regrow and reset. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1688–1696. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monga S.P. Hepatic regenerative medicine: exploiting the liver's will to live. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:306–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karp S.J. Clinical implications of advances in the basic science of liver repair and regeneration. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1973–1980. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Columbano A., Simbula M., Pibiri M., Perra A., Deidda M., Locker J., Pisanu A., Uccheddu A., Ledda-Columbano G.M. Triiodothyronine stimulates hepatocyte proliferation in two models of impaired liver regeneration. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:521–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kowalik M.A., Perra A., Pibiri M., Cocco M.T., Samarut J., Plateroti M., Ledda-Columbano G.M., Columbano A. TRbeta is the critical thyroid hormone receptor isoform in T3-induced proliferation of hepatocytes and pancreatic acinar cells. J Hepatol. 2010;53:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledda-Columbano G.M., Molotzu F., Pibiri M., Cossu C., Perra A., Columbano A. Thyroid hormone induces cyclin D1 nuclear translocation and DNA synthesis in adult rat cardiomyocytes. FASEB J. 2006;20:87–94. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4202com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pibiri M., Ledda-Columbano G.M., Cossu C., Simbula G., Menegazzi M., Shinozuka H., Columbano A. Cyclin D1 is an early target in hepatocyte proliferation induced by thyroid hormone (T3) FASEB J. 2001;15:1006–1013. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0416com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apte U., Singh S., Zeng G., Cieply B., Virji M.A., Wu T., Monga S.P. Beta-catenin activation promotes liver regeneration after acetaminophen-induced injury. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1056–1065. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhushan B., Walesky C., Manley M., Gallagher T., Borude P., Edwards G., Monga S.P., Apte U. Pro-regenerative signaling after acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury in mice identified using a novel incremental dose model. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:3013–3025. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goessling W., North T.E., Lord A.M., Ceol C., Lee S., Weidinger G., Bourque C., Strijbosch R., Haramis A.P., Puder M., Clevers H., Moon R.T., Zon L.I. APC mutant zebrafish uncover a changing temporal requirement for wnt signaling in liver development. Dev Biol. 2008;320:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.05.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monga S.P. Role and regulation of [beta]-catenin signaling during physiological liver growth. Gene Expr. 2014;16:51–62. doi: 10.3727/105221614X13919976902138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nejak-Bowen K.N., Thompson M.D., Singh S., Bowen W.C., Jr., Dar M.J., Khillan J., Dai C., Monga S.P. Accelerated liver regeneration and hepatocarcinogenesis in mice overexpressing serine-45 mutant beta-catenin. Hepatology. 2010;51:1603–1613. doi: 10.1002/hep.23538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarin S.K., Choudhury A. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: terminology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:131–149. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledda-Columbano G.M., Perra A., Loi R., Shinozuka H., Columbano A. Cell proliferation induced by triiodothyronine in rat liver is associated with nodule regression and reduction of hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2000;60:603–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perra A., Kowalik M.A., Pibiri M., Ledda-Columbano G.M., Columbano A. Thyroid hormone receptor ligands induce regression of rat preneoplastic liver lesions causing their reversion to a differentiated phenotype. Hepatology. 2009;49:1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/hep.22750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sangwan V., Paliouras G.N., Abella J.V., Dube N., Monast A., Tremblay M.L., Park M. Regulation of the Met receptor-tyrosine kinase by the protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B and T-cell phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34374–34383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805916200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]