Abstract

Chromolaena odorata is a major bio-resource in folkloric treatment of diabetes. In the present study, its anti-diabetic component and underlying mechanism were investigated. A library containing 140 phytocompounds previously characterized from C. odorata was generated and docked (Autodock Vina) into homology models of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)-4, Takeda-G-protein-receptor-5 (TGR5), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor, renal sodium dependent glucose transporter (SGLUT)-1/2 and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) proteins 1&2. GLP-1 gene (RT-PCR) modulation and its release (EIA) by C. odorata were confirmed in vivo. From the docking result above, TGR5 was identified as a major target for two key C. odorata flavonoids (5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone and homoesperetin-7-rutinoside); sodium taurocholate and C. odorata powder included into the diet of the animals both raised the intestinal GLP-1 expression versus control (p < 0.05); When treated with flavonoid-rich extract of C. odorata (CoF) or malvidin, circulating GLP-1 increased by 130.7% in malvidin-treated subjects (0 vs. 45 min). CoF treatment also resulted in 128.5 and 275% increase for 10 and 30 mg/kg b.w., respectively. Conclusions: The results of this study support that C. odorata flavonoids may modulate the expression of GLP-1 and its release via TGR5. This finding may underscore its anti-diabetic potency.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-018-1138-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: C. odorata, Flavonoids, TGR5, GLP-1

Introduction

The International Diabetes Federation Africa (IDFA) had reported that 14 million Africans are diabetic, with a projection of 34.2 million in 2040 (Foundation 2016). In 2015, alone, 321,000 diabetes-related deaths were recorded. Given the socioeconomic impact of diabetes, a rapid and highly scalable solution in tackling this epidemic is imperative. Given that most countries in Africa are ranked as low- and medium-income countries, a cost-effective option is an absolute must. Treatment strategy for Type-2 diabetes relies predominantly on improved metabolic status of the patient (Scheen 2003; Scheen and Paquot 2015) while type-1 diabetes is amenable to insulinotropic drugs (Atkinson 2012; D’Alessio 2010). Current pharmacological intervention is rather inaccessible to patients in low- and medium-income demography due to socioeconomic constraints; thus promoting an argument for alternative therapeutic options if current epidemiology and future projections must be averted.

According to folklore, one of the most effective treatment options for diabetes is extract of Chromolaena odorata L. which has been backed up by some scientific evidence (Adedapo et al. 2016; Onkaramurthy et al. 2013). Studies linking specific C. odorata phtocompounds to anti-diabetic actions are still scarce; and may delay drug-development plans. This study benefitted from previous phytochemical characterization efforts on C. odorata and the current understanding of clinical and experimental targets for anti-diabetic drugs. In all, a total of 140 phytocompounds were curated and computationally screened against anti-diabetic targets. Dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)-4 (Barnett 2006), Takeda-G-protein-receptor-5 (G protein-coupled bile acid receptor, TGR5) (Genet et al. 2009), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor (Drucker and Nauck 2006), renal sodium dependent glucose transporter (SGLUT)-1/2 (Meng et al. 2008) and nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-1/2 (Shiny et al. 2013) were chosen as they represent pharmacological targets for staglipin, 3-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-(4-chlorophenyl)-N,5-dimethyl-4-isoxazolecarboxamide, GLP1, ertugliflozin, and GSK717, respectively, which have proven anti-diabetic potencies.

From the computational studies, 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone and homoesperetin-7-rutinoside were identified as putative anti-diabetic compounds from C. odorata targeting TGR5. Since both compounds are of flavonoid class, total flavonoid was isolated, validated and tested in vivo for serum GLP-1 release. Since GLP-1 is insulinotropic, flavonoids of C. odorata may therefore represent another therapeutic strategy for managing diabetes (Lokman et al. 2013; Oh 2015; Shen et al. 2012).

Experimental

Library generation, docking and scoring

Previously identified and characterized compounds of C. odorata were retrieved from PubChem using ChemAxon suite (https://www.chemaxon.com). The library was docked (Autodock Vina)(Seeliger and de Groot 2010) into the active sites of the homology models (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) (Schwede et al. 2003) of DPP-4 (Barnett 2006), TGR5 (Genet et al. 2009), GLP-1 receptor (Drucker and Nauck 2006), SGLUT-1/2 (Meng et al. 2008) and NOD-1/2 (Shiny et al. 2013). The templates for the model were carefully selected to reflect inhibitor-bound conformation in DPP4 (template = 6B1O, DPP4 in complex with vildagliptin analog, 1.91 Å), SGLUT-1/2 ((template = 3dh4, Crystal Structure of Sodium/Sugar symporter with bound Galactose from vibrio parahaemolyticus, 2.70 Å) (Faham et al. 2008) and NOD-1/2 (template = 4JQW, Crystal Structure of a Complex of NOD1 CARD and Ubiquitin, 2.9 Å) (Ver Heul et al. 2014) while TGR5 (template = 3QAK, agonist bound structure of the human adenosine A2a receptor, 2.7A resolution) (Xu et al. 2011) and GLP-1 receptor (template = 5NX2, GLP-1R in complex with a truncated peptide agonist, 3.7 A resolution) (Jazayeri et al. 2017) were modeled in active states. In each case, the binding site is defined by 25 cm by 25 cm by 25 cm rectangular box around the mean coordinate of the co-crystallized ligand and in case of NOD without ligand, Nodinitb-1 (ML130, CID 1088438) (Kecek Plesec et al. 2016) retrieved from the PubChem database was docked into the NOD using the BSP-SLIM portal as previously reported (Omotuyi and Ueda 2015). Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) in AutoDock was used to generate conformations of the C. odorata compounds. Ten docking runs were performed, with an initial population of 150 random individuals and a maximum number of 2,500,000 energy evaluations as successfully implemented in previous studies (Morris et al. 2009).

GLP-1 gene expression

All protocols related to animal studies were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Centre for Research and Development (CRD), Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko. C. odorata powder (n = 5) and sodium taurocholate (Sigma-Aldrich, n = 5) were formulated into rat feed (5%, feed 95%), and compared with the control (feed = 100%, n = 3). The bitter taste of the treatments was masked using locally sourced honey (100 ml/100 g formulated fed and control group). Animals were allowed to feed ad libitum for 14 h followed by 8 h feed withdrawal. RNA was isolated from the proximal end of the ligated ileum using TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). DNA contaminant was removed following DNAse I treatment (ThermoFisher Scientific) following manufacturer’s protocol. Purified DNA-free RNA was converted to cDNA immediately using ProtoScript® First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (NEB). PCR amplification was done using OneTaq® 2X Master Mix (NEB) using the following primer set: (GLP-1-Forward-primer-5′-TCCCAAAGGAGCTCCACCTG-3′/Reverse-primer-5′-TTCTCCTCCGTGTCTTGAGGG-3′; β-Actin-(control)-β-Actin-Foward-primer-5′-GTCGAGTCCGCGTCCAC-3′/Reverse-primer-5′-AAACATGATCTGGGTCATCTTTTCACG-3′). GLP-1. Representative snapshot of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-agarose gel electrophoresis data of Na-taurocholate (Na-T) and C. odorata fed Wistar rats. The band density (Image-J)(Schneider et al. 2012) is plotted as a bar graph (mean ± SEM, n = 3–5).

Flavonoid isolation, characterization, and serum GLP-1 estimation

Flavonoids were isolated from fresh samples of C. odorata using HCL (1%, v/v) as previously documented (Omotuyi et al. 2013) and purified using DOWEX-50 column (Raman et al. 2004) resulting in C. odorata flavonoids (CoF). CoF HPLC characterization has been described elsewhere (Mattila et al. 2000). Serum GLP-1(EIA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol) was assayed before (0 min) and after oral administration (45 min) of CoF (n = 5), and compared to malvidin chloride (MaL, n = 5) (Sigma-Aldrich) and untreated control animals (n = 3) as previously described (Phuwamongkolwiwat et al. 2014).

Results and discussion

Dysregulated glucose homeostasis underlies diabetes mellitus and its microvascular complications. Glucose homeostasis may be altered by autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells or insulin resistance. Therefore, diabetic patients have benefitted from exogenous insulin, treatment strategies that improve endogenous insulin production, reduce obesity and restores energy balance. GLP-1 secretagogues (acting via TGR5 activation) (Cao et al. 2016) and GLP-1 analogs are particularly interesting in clinical settings as they enhance the biological actions of GLP-1 such as promoting β cells proliferation and function (insulin synthesis and GLP-1 receptor-mediated insulin secretion), suppressing gut motility and appetite. GLP-1 is short-lived, rapidly metabolized by serum DPP-4 (Beck-Nielsen 2012; Lee 2016; Yu et al. 2015). Another clinically useful strategy is to elongate GLP-1 by inhibiting DPP-4 (Yu et al. 2015). Recently, NOD-like receptors (NOD1 and NOD2) are now recognized as critical factors in HFD (high-fat diet)-induced pancreatic inflammation and insulin intolerance (Schertzer et al. 2011) and the clinical application of its antagonists is now under intensive investigation (Moreno and Gatheral 2013). Another clinical target for diabetes is the sodium–glucose co-transporter (SGLT)-2(Mudaliar et al. 2015). Inhibitors of SGLT2 prevent renal glucose reabsorption enhances urinary glucose excretion with concomitant reduction in plasma glucose levels (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Graphical abstract. The contribution of pancreas, intestinal L-cell, kidney and blood factors in the development of novel anti-diabetic agents

Identification of TGR5 as C. odorata phytocompounds target

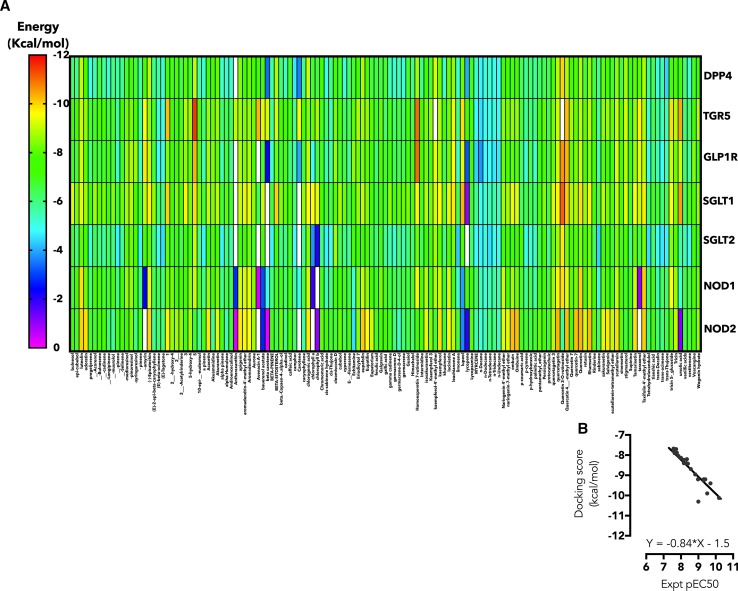

The first question in this study is which of these targets may explain the anti-diabetic potency of C. odorata? To answer this, a library of 140 phytocompounds was created for C. odorata (supplementary information 1) based on previous reports of isolation and structural characterization. Docking results for each targets detailed above are represented as a heat map (Fig. 2a). Although, several phytochemicals of C. odorata have high affinity (− 9.0 to − 12.0 kcal/mol; yellow to red spectrum) for TGR5, GLP1R and SGLT1, It is of interest to note that 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone and homoesperetin-7-rutinoside are further interest as they showed the lowest binding energy overall for TGR5; calculated as − 11.5 and − 11.0 kcal/mol, respectively, compared with − 9.4 kcal/mol for 6α-Ethyl-23(S)-methylcholic Acid (INT-777) a well-studied TGR5 agonist. To validate the computational data obtained for TGR5, 45 agonists with EC50 records were downloaded from the ChemBL database, prepared and docked into the TGR5 model used for C. odorata screening. A line graph of experimental versus docking score showed the equation: with the correlation coefficient (r2) = 0.75 (Fig. 2b). Next, the binding poses were studied to determine the residues involved in TGR5 interaction. INT-777 relied on hydrophobic interaction with Phe-96, Tyr-89, Leu-141, Leu-244, Leu-266, Leu-71 and hydrophobic interaction with Asn-77 (Fig. 3a). The fused rings of 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone is stabilized by hydrophobic interaction with Leu-262/266 residues. The detached A-ring forms hydrophobic interaction with Pro-164 and Leu-168. Ser-156 and Tyr-240 may also play key roles in stabilizing the interaction between TGR5 and 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone (Fig. 3b). Homoesperetin-7-rutinoside tends to utilize all the residues highlighted in INT-777 and 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone complexes and may also benefit from enhanced hydrophilic interaction resulting from the presence of rutinoside residue (Fig. 3c). While further experimental study was focused on TGR5 effects, it is worthy of note to add that homoesperetin-7-rutinoside also demonstrated low binding energy for GLP1R (− 11.0 kcal/mol) and quercetin 3-O-rutinoside show a low binding energy for SGLT1 (− 11.0 kcal/mol) but not SGLT2 (− 9.8 kcal/mol, binding pose not shown).

Fig. 2.

Heat map representation of docking result. The free energy of binding of phytochemicals of C. odorata docked into the substrate-binding sites of DPP4, TGR5, GLP1R, SGLT1, SGLT2, NOD1 and NOD2 are represented as heat map. (The scale is a spectrum from pink (0 kcal/mol) to red (− 12 kcal/mol). b The correlation plot of pEC50 (experimental, CHEMBL5409) versus docking score (Autodock Vina)

Fig. 3.

Binding poses of select C. odorata phytochemicals in the orthosteric site of TGR5. 6α-Ethyl-23(S)-methylcholic Acid (INT-777, cyan stick representation), a known TGR5 (green cartoon) agonist was docked into TGR5 model using BSP-SLIM method and re-docked using Autodock Vina for validation (a). 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone (Fig. 2b; pink stick representation) and Homoesperetin-7-rutinoside (Fig. 2c; yellow stick representation) were docked (Autodock Vina) into TGR5 using INT-777 as reference ligand. Residues participating in the interaction of each ligand are displayed on top of each complex

Diet-included C. odorata alters GLP-1 gene expression in the ileum

If TGR5 is indeed a key target of C. odorata phytocompounds, then it should promote GLP-1 gene expression profile, therefore, C. odorata powder and sodium taurocholate (Na-T) were introduced into the feed of the subjects as described in the experimental section followed by determination of GLP-1 gene expression in proximal end of the ligated ileum. In the treatment groups, GLP-1 was significantly upregulated (n = 3–5 animals, p > 0.05 vs. untreated control) but no statistically significant difference was observed between sodium taurocholate and C. odorata treatments (Fig. 4). This finding further lends credence to the anti-diabetic effects of dietary flavonoids and further reveals a possible mechanism via enhanced GLP-1 production, insulin secretion, pancreatic β-cells proliferation. Ultimately resulting in hypoglycemia, reduced insulin resistance and increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue (Babu et al. 2013). The result is consistent with previous findings that phenolics from berries upregulated insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, insulin-like growth factor 2, insulin-like growth factor binding proteins, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and GLP-1 genes in iNS-1E cells (Johnson and de Mejia 2016).

Fig. 4.

Intestinal GLP-1 expression in C. odorata fed Wistar rats. Representative snapshot of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-agarose gel electrophoresis data of Na-taurocholate (Na-T) and C. odoata fed Wistar rats. The band density (Image-J) (Schneider et al. 2012) is plotted as a bar graph (mean ± SEM, n = 3–5)

C. odorata flavonoid improves plasma GLP-1

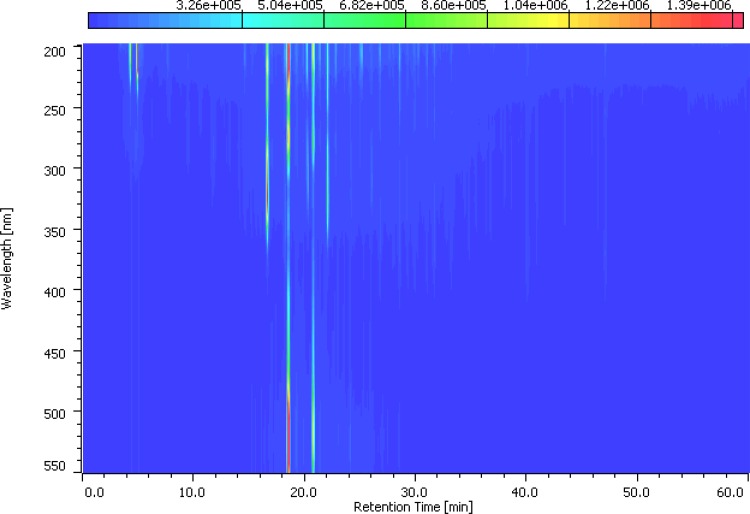

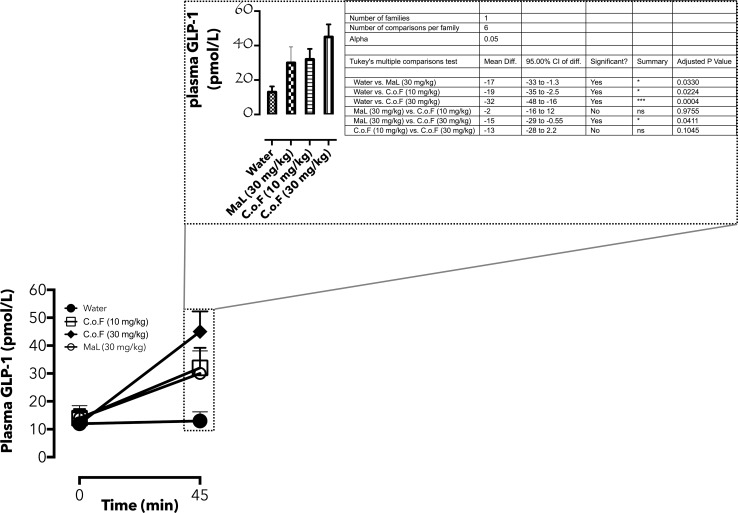

5% C. odorata in rat feed is a complex mixture of several phytochemicals and increased in GLP-1 gene expression may not be due to flavonoids alone. Therefore, heterogeneous flavonoids from fresh samples of C. odorata (CoF) were isolated as described previously (Omotuyi et al. 2013) and purified (Raman et al. 2004). Flavonoids from C. odorata absorbed at 230/530 nm following HPLC fractionation (Fig. 5). CoF was compared with malvidin chloride (MaL) and untreated control animals for plasma GLP-1 release as previously described (Phuwamongkolwiwat et al. 2014). Blood was drawn from animals (0 min, female Wistar rats, 8 weeks old, n = 3) previously fasted for 24 h and following 1 mL oral doses (0 (water, control), 30 (MaL), 10, 30 (CoF) mg/kg b.w.) of treatment materials after 45 min post administration. GLP-1 data showed no significant difference in the circulating GLP-1 in the pre-treated animals, but following MaL (30 mg/kg), circulating GLP-1 levels increased by 130.7% (vs. water control). CoF treatment resulted in 128.5 and 275% increase for 10 and 30 mg/kg b.w, respectively, in comparison with the water-treated control (Fig. 6). Post-treatment, circulating GLP-1 is significantly higher in CoF-treated (30 mg/kg, b.w) group compare with the MaL-treated animals (Adjusted P value = 0.04, inset, Fig. 6). This data lend credence to the previous reports that non-nutritive components of plant especially the flavonoid class have GLP-1 secretory properties. The authors specifically identified delphinidin 3-rutinoside (D3R) as GLP-1 secretagogue in GLUTag L cells (Kato et al. 2015). Furthermore, aromatic ring of flavonoids containing three hydroxyl, two methoxyl moieties, or rutinose may be essential for GLP-1 stimulation. Although this study relied on computation for proposing the plausible target for C. odorata flavonoids, Kato et al. (Kato et al. 2015) suggested that D3R stimulated GLP-1 secretion in GLUTag cells via GPR40/120-mediated Ca2+-CaMKII pathway.

Fig. 5.

HPLC-DAD profile of CoF: HPLC chromatogram of C. odorata flavonoid-rich extract following a 60 min-elution at 1 mL/min flow rate in acetonitrile, 0.1% HCOOH in water. Detector was scanned between 200 and 500 nm

Fig. 6.

Plasma GLP-1 dynamics in anthocyanin-enriched C. odorata extract-treated Wistar rats. The line graph represents circulating GLP-1 in pre- (0 min) and post-treated (45 min) animals. Post-treatment values are also represented as bar graphs (mean ± SEM, n = 3–5) and subjected to ANOVA analysis (inset)

Conclusion

This study investigated the putative anti-diabetic principle in C. odorata and its underlying mechanisms using in silico and in vivo experiments. 5,7-dihydroxy-6-4-dimethoxyflavanone and homoesperetin-7-rutinoside are the major C. odorata compounds with high affinity for TGR5. Normal rats fed C. odorata-based food or administered flavonoid-rich extract of C. odorata showed increased blood GLP-1 release compared with their control littermates. Interestingly, the results demonstrate that C. odorata may represent key bio-resource for the development of cheap anti-diabetic drugs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13205-018-1138-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Adedapo AA, Ogunmiluyi IO, Adeoye AT, Ofuegbe SO, Emikpe BO. Evaluation of the medicinal potential of the methanol leaf extract of Chromolaena odorata in some laboratory animals. J Med Plants. 2016;4:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson MA. The pathogenesis and natural history of type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu PV, Liu D, Gilbert ER. Recent advances in understanding the anti-diabetic actions of dietary flavonoids. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24:1777–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A. DPP-4 inhibitors and their potential role in the management of type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:1454–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Nielsen H. Glucagon-like peptide 1 analogues in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ugeskr Laeger. 2012;174:1606–1608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Chen ZX, Wang K, Ning MM, Zou QA, Feng Y, Ye YL, Leng Y, Shen JH. Intestinally-targeted TGR5 agonists equipped with quaternary ammonium have an improved hypoglycemic effect and reduced gallbladder filling effect. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28676. doi: 10.1038/srep28676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessio DA. Taking aim at islet hormones with GLP-1: is insulin or glucagon the better target? Diabetes. 2010;59:1572–1574. doi: 10.2337/db10-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. The Lancet. 2006;368:1696–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faham S, Watanabe A, Besserer GM, Cascio D, Specht A, Hirayama BA, Wright EM, Abramson J. The crystal structure of a sodium galactose transporter reveals mechanistic insights into Na+/sugar symport. Science. 2008;321:810–814. doi: 10.1126/science.1160406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foundation ID (2016) Executive summary in IDF diabetes. Atlas

- Genet C, Strehle A, Schmidt C, Boudjelal G, Lobstein A, Schoonjans K, Wagner A. Structure–activity relationship study of betulinic acid, a novel and selective TGR5 agonist, and its synthetic derivatives: potential impact in diabetes. J Med Chem. 2009;53:178–190. doi: 10.1021/jm900872z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri A, Rappas M, Brown AJH, Kean J, Errey JC, Robertson NJ, Fiez-Vandal C, Andrews SP, Congreve M, Bortolato A, Mason JS, Baig AH, Teobald I, Dore AS, Weir M, Cooke RM, Marshall FH. Crystal structure of the GLP-1 receptor bound to a peptide agonist. Nature. 2017;546:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature22800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, de Mejia EG. Phenolic compounds from fermented berry beverages modulated gene and protein expression to increase insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:2569–2581. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Tani T, Terahara N, Tsuda T. The anthocyanin delphinidin 3-rutinoside stimulates glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in murine GLUTag cell line via the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II pathway. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0126157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kecek Plesec K, Urbancic D, Gobec M, Pekosak A, Tomasic T, Anderluh M, Mlinaric-Rascan I, Jakopin Z. Identification of indole scaffold-based dual inhibitors of NOD1 and NOD2. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24:5221–5234. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY. Glucagon-like peptide-1 formulation–the present and future development in diabetes treatment. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;118:173–180. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokman FE, Gu HF, Wan Mohamud WN, Yusoff MM, Chia KL, Ostenson CG. Antidiabetic effect of oral borapetol B compound, isolated from the plant Tinospora crispa, by stimulating insulin release. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:727602. doi: 10.1155/2013/727602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila P, Astola J, Kumpulainen J. Determination of flavonoids in plant material by HPLC with diode-array and electro-array detections. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:5834–5841. doi: 10.1021/jf000661f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W, Ellsworth BA, Nirschl AA, McCann PJ, Patel M, Girotra RN, Zahler R. Discovery of dapagliflozin: a potent, selective renal sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2008;51:1145–1149. doi: 10.1021/jm701272q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno L, Gatheral T. Therapeutic targeting of NOD1 receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:475–485. doi: 10.1111/bph.12300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudaliar S, Polidori D, Zambrowicz B, Henry RR. Sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors: effects on renal and intestinal glucose transport: from bench to bedside. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:2344–2353. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh YS. Plant-derived compounds targeting pancreatic beta cells for the treatment of diabetes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:629863. doi: 10.1155/2015/629863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omotuyi OI, Ueda H. Molecular dynamics study-based mechanism of nefiracetam-induced NMDA receptor potentiation. Comput Biol Chem. 2015;55:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omotuyi IO, Elekofehinti OO, Ejelonu OC, Obi FO. Mass spectra analysis of H. sabdarifia L anthocyanidins and their in silico corticosteroid-binding globulin interactions. Pharmacol OnLine. 2013;1:206–217. [Google Scholar]

- Onkaramurthy M, Veerapur VP, Thippeswamy BS, Reddy TM, Rayappa H, Badami S. Anti-diabetic and anti-cataract effects of Chromolaena odorata Linn., in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuwamongkolwiwat P, Hira T, Hara H. A nondigestible saccharide, fructooligosaccharide, increases the promotive effect of a flavonoid, α-glucosyl-isoquercitrin, on glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secretion in rat intestine and enteroendocrine cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:1581–1584. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman G, Jayaprakasha GK, Brodbelt J, Cho M, Patil BS. Isolation of structurally similar citrus flavonoids by flash chromatography. Anal Lett. 2004;37:3005–3016. doi: 10.1081/AL-200035884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Acta Clin Belg. 2003;58:335–341. doi: 10.1179/acb.2003.58.6.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheen AJ, Paquot N. 2015 updated position statement of the management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Rev Med Suisse. 2015;11(1518):1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schertzer JD, Tamrakar AK, Magalhaes JG, Pereira S, Bilan PJ, Fullerton MD, Liu Z, Steinberg GR, Giacca A, Philpott DJ, Klip A. NOD1 activators link innate immunity to insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2011;60:2206–2215. doi: 10.2337/db11-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeliger D, de Groot BL. Ligand docking and binding site analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2010;24:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s10822-010-9352-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Shao M, Cho KW, Wang S, Chen Z, Sheng L, Wang T, Liu Y, Rui L. Herbal constituent sequoyitol improves hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance by targeting hepatocytes, adipocytes, and beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E932–E940. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00479.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiny A, Regin B, Balachandar V, Gokulakrishnan K, Mohan V, Babu S, Balasubramanyam M. Convergence of innate immunity and insulin resistance as evidenced by increased nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD) expression and signaling in monocytes from patients with type 2 diabetes. Cytokine. 2013;64:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ver Heul AM, Gakhar L, Piper RC, Subramanian R. Crystal structure of a complex of NOD1 CARD and ubiquitin. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Wu H, Katritch V, Han GW, Jacobson KA, Gao ZG, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure of an agonist-bound human A2A adenosine receptor. Science. 2011;332:322–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1202793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu OH, Yin H, Azoulay L. The combination of DPP-4 inhibitors versus sulfonylureas with metformin after failure of first-line treatment in the risk for major cardiovascular events and death. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.