Abstract

Oxymatrine extracted from Sophora flavescens Ait as a natural polyphenolic phytochemical has been demonstrated to exhibit anti-tumor effects on various cancers, including Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC). However, its underlying mechanisms of function are largely unknown in GBC cells. The present study is conducted to investigate the anti-tumor effects and the underlying mechanisms of oxymatrine on GBC cells in vitro and in vivo. The results showed that oxymatrine inhibited cell viability, metastatic ability and induced cell apoptosis in dose-dependent manners. Furthermore, we found that the expression of p-AKT, MMP-2, MMP-9 and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax were significantly down-regulated, while the expression of PTEN was up-regulated in GBC cells. In addition, pretreatment with a specific PI3K/AKT activator (IGF-1) significantly antagonized the oxymatrine-mediated inhibition of GBC–SD cells. Subsequently, our in vivo studies showed that administration of oxymatrine induced a significant dose-dependent decrease in tumor growth. In conclusion, these findings indicated that the inhibition of cells proliferation, migration, invasion and the induction of apoptosis in response to oxymatrine in GBC cells, may function through the suppression of PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway, which was considered as the vital signaling pathway in regulating tumorigenesis. These results suggested that oxymatrine might be a novel effective candidate as chemotherapeutic agent against GBC.

Keywords: Oxymatrine, Gallbladder carcinoma, Invasion, PTEN, AKT

Introduction

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC), the most common biliary tract cancer, is the fifth common malignant tumor of the digestive tract, with an incidence of 1–2 cases/100,000 worldwide (Miller and Jarnagin 2008). However, it is more common in China, with the incidence up to 96 cases/100,000 (Khan et al. 2008; Jia et al. 2011). Unfortunately, owing to its highly invasive nature and a lack of specific signs, most patients are at an advanced stage when the diagnosis is made (Li et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013a, b). Surgical resection is the only potentially curative therapy for GBC. Unfortunately, owing to its highly invasive nature and a lack of specific signs and symptoms, most patients are usually detected at an advanced stage. Therefore, only a minority of patients are candidates for curative resection. Moreover, the majority of patients suffer recurrences after surgery. As a result, GBC is associated with an extremely poor prognosis, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 10% (Tan et al. 2013; Boutros et al. 2012). For recurrence and unresectable patients, palliative therapy, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are always introduced to improve prognosis; however, it does not have satisfactory results (Sharma et al. 2010; Abahssain et al. 2010). Therefore, novel agents and effective treatments are urgently needed for the treatment of advanced GBC.

Plant-derived agents tend to be more structurally diverse “drug-like” and “biologically friendly” molecular qualities than synthetic compounds at random (Pan et al. 2010). Therefore, it is an important sources of anti-tumour drug. There is an increasing number of plant-derived antitumor drugs of various structural types both in clinical use and as anticancer candidates (And and Cragg 2007; Valeriote et al. 2015; Butler 2008). Ku Shen, is the dried root of Sophora flavescens Aiton (Leguminosae), has been used as folk medicine for a long time. Compound Kushen Injection (CKI) has been used for cancer patients in Chinese clinical settings for many years. The efficacy of CKI is evaluated in cancer patients either alone or in conjunction with radiotherapeutic or chemotherapeutic treatments (Lao 2005; Shao 2011; Sun et al. 2012a, b). Oxymatrine (OM; C15H24N2O2; Fig. 1), the main tetracycloquinolizindine alkaloid present in Ku Shen, may act as the specific active ingredient that exhibits a variety of pharmacological effects such as anti-hepatic fibrosis (Chai et al. 2012), anti-hepatitis virus infection (Wang et al. 2011a, b), anti-arrhythmic potential (Cao et al. 2010), and anti-inflammation (Gu et al. 2012). Recently, OM has attracted much more attentions because of its low toxicity and potential anticancer effects. It is believed that the anticancer activity of OM is mainly in inducing the apoptosis of cancer cells (Qin et al. 2009; Song et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2013a, b) and suppressing metastasis (Guo et al. 2015; Li et al. 2015). Accumulating researchs suggest that the mechanism may associate with decrease of Bcl-2/Bax and the expression of Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and CD44v6 protein (Liu et al. 2014; Dai et al. 2007). However, the upstream target of OM is rarely studied. In addition, up to now, there was no research on the anti-metastatic effect of OM on GBC cells.

Fig. 1.

The chemical structure of oxymatrine

In the present study, we attempted to determine whether OM could inhibit the proliferation and invasion of, and induce apoptosis in GBC cells and to clarify the related mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Drugs and antibodies

OM was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and then diluted with culture medium to make stock solutions of 10 mg/mL. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.3% in cell culture. The primary antibodies, including rabbit anti-human total-Akt, rabbit anti-human phospho-AKT (Thr308), rabbit anti-human phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN), rabbit anti-human matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), rabbit anti-human matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The mouse anti-human Bcl-2 and Bax antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody was purchased from Kangchen Bio-tech (Shanghai, China). The secondary antibodies, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Cell lines and culture

The GBC–SD and SGC-996 cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The GBC–SD cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator, while the SGC-996 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI; Gibco) 1640 medium. The two types of culture medium were both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco). The cells were kept in an exponential growth phase during experiments.

Assessment of cell viability

The effects of OM on the viability of GBC–SD and SGC-996 cells were determined by MTT assay. The cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured overnight at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, the cells were replenished with fresh medium containing various concentrations of OM (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0 and 8.0 mg/mL) for 24, 48 and 72 h. Then, 20 μL of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in PBS at 5 mg/mL was added to each well and the mixture was incubated in darkness for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Thereafter, the growth medium was removed and 150 µL DMSO was added to each well. The absorbance values at 490 nm were measured by micro-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The inhibition rate for the proliferation of cells was calculated according to the formula: [1 − A490 (test)/A490 (control)] × 100%.

Plate colony-forming assay

The GBC–SD cells were detached into single cell suspension and seeded into 12-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 500 cells/well. After adherence, cells were treated with OM (0, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h. Then, the complete medium replaced the OM-containing medium. The cells were allowed to form colonies in complete medium for 14 days and the medium was replaced every three days. The cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet at room temperature for 15 min and the stained colonies that contained ≥ 50 cells were counted.

Hoechst 33342 staining

The apoptosis of GBC–SD cells treated with OM was determined by Hoechst 33342 staining. Briefly, the cells were exposed to OM (0, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h. Thereafter, the cultured cells on glass coverslips were fixed and stained with 10 μg/mL of Hoechst 33342 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 10 min in the dark. After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the samples were observed by an inverted fluorescence microscope (200×). The nuclei having significant morphological changes and the apoptotic cells were identified by their dense nuclei or densely stained fragments.

Annexin V–FITC/PI staining

The GBC–SD cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and incubated with different concentration of OM (0, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h. The cells were then harvested and washed with PBS twice. Thereafter, the cells were resuspended with 500 µL binding buffer (1×) and stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI (MultiSciences Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 15 min in the dark. Then the cells were detected by flow cytometry (Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) within 1 h after staining.

Wound healing assay

GBC–SD cells were grown in six-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well and grown to confluence. Wound was created by a sterile micro-pipette tip and washed with PBS to remove the floating cells. The cells were treated with different concentrations of (0, 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9 mg/mL) OM for 48 h, and the migration distance was measured and analyzed.

Migration and invasion assays

The migration and invasion of GBC–SD cells were evaluated by transwell chamber assay (8.0 μm pore size, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). For invasion assay, each chamber was precoated with 100 μL of a 1:6 diluted matrigel (BD Biosciences, Shanghai, China) in cold DMEM, while the cell migration assay was performed without coating with matrigel. 5 × 104 cells in 200 μL serum-free medium were added into the upper chambers and 500 μL medium (10% FBS) was added into the bottom chambers. GBC–SD cells were exposed to OM at concentrations of 0, 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9 mg/mL for 48 h, respectively. Then the invaded cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet for 10–15 min. The cells in 5 randomly selective fields were counted.

Western blot analysis

GBC–SD cells were plated in six-well plates and treated with OM (0, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h. Thereafter, the cells were lysed with 200 μL lysis buffer, followed by denaturation. The protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay system (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) with BSA as a standard. Equal quantities (80 μg protein per lane) of each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE (10 or 12%) and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The membranes were subsequently blocked by defatted milk (5% in Tris-buffered saline with TWEEN-20 (TBST) buffer) for 1 h at the room temperature. Then, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against PTEN, AKT, p-AKT, MMP-2, MMP-9, Bcl-2, Bax, GAPDH overnight at 4 °C. Thereafter, the membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. After each incubation period, the membranes were washed with TBST for three times. The blots were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific, Shanghai, China). The blots were semi-quantified by Image J software. Equal protein loading was assessed by the expression of GAPDH.

In vivo efficacy of OM

Fifteen BALB/C male nude mice (4 weeks old) were obtained from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Protocols for animal experiments were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Xuzhou Medical University. All animals were maintained throughout in specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment. GBC–SD cells (2 × 106) were suspended in 150 μL PBS and subcutaneously injected into the right axillary fossa of each mouse. After one week, the mice were randomized into three groups (n = 5 per group). Thereafter, the treatment groups were injected intravenously at two doses of OM (50 and 100 mg/kg) on alternative days, respectively. Meanwhile, physiological saline was administered to the negative control group. All mice were administered ten times and killed one week after treatment, and the tumors were dissected and weighed. The tumor volume (TV) was calculated by the formula: TV = 0.5 × a × b2, in which a and b represent the maximal and minimal diameters.

The tumor tissues were fixed in neutral formalin and embedded in paraffin. Then the specimens were sectioned at 3 μm and the expression of PTEN, MMP-2 and Ki67 (mouse anti-Ki67 antibody: GeneTex Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) were examined by immunohistochemistry with the streptavdin–peroxidase (S–P) kit (Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Fuzhou, China). The percentages of positive cells were enumerated in each section under five fields of medium magnification (400×).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 17.0 statistical software. Experiments were repeated three independent times and all data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, while t test (Student test) was used to compare two groups. All statistical tests were two-sided. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significance.

Results

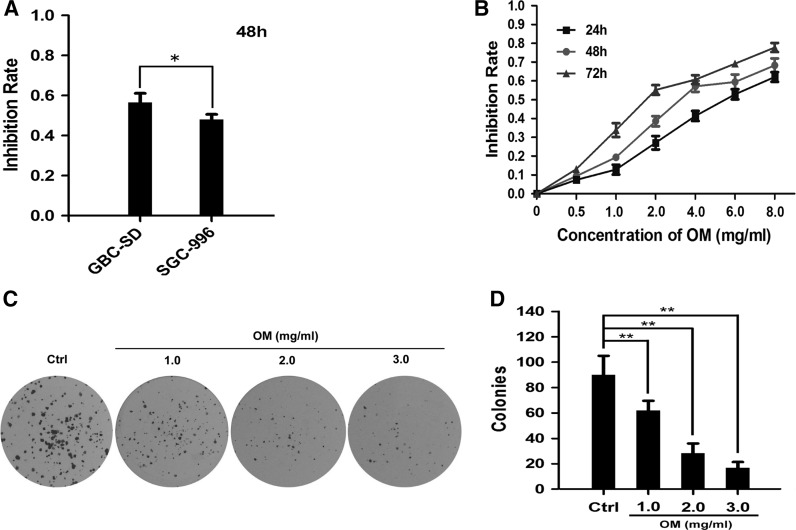

OM inhibits the proliferation of GBC–SD cells

The MTT assay was carried out to test the proliferation inhibition effects of OM on GBC–SD and SGC-996 cells. Cells were treated with OM at a concentration of 4 mg/mL for 48 h. The results demonstrated that GBS–SD cells were more sensitive to OM than SGC-996 cells (Fig. 2a). Therefore, GBC–SD cells were used in the subsequent experiments. Then, GBC–SD cells were treated with OM at different concentrations for 24, 48 and 72 h. The results showed that OM can inhibit the proliferative activity of GBC–SD cells in a dose- and time- dependent manner (Fig. 2b). The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of GBC–SD cells at 24, 48 and 72 h were approximately 5.02 ± 0.28, 3.18 ± 0.24 and 1.95 ± 0.28 mg/mL, respectively. According to the curve, we chose 0, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 mg/mL as the concentration range in the following experiments. Additionally, the plate colony-formation assay was done to investigate the effect of OM on the proliferation of GBC–SD cells. Similarly, the number of colonies of OM-treated GBC–SD cells was significantly lower than that in the control group (Fig. 2c, d). These findings indicated that OM has an anti-proliferative effect on GBC–SD cells.

Fig. 2.

Effect of OM on the proliferation of GBC cells. a The GBC–SD and SGC-996 cells were treated with OM at a concentration of 4.0 mg/mL for 48 h; the inhibition rates were examined and compared; *P < 0.05. b GBC–SD cells were treated with OM at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0 and 8.0 mg/mL for 24, 48 and 72 h, and the inhibition rates were determined by MTT assay. c, d Colony formation assay was used to confirm the growth-inhibitory effect of OM against GBC–SD cells for 48 h (c), and the colonies from three independent experiments were counted and compared; **P < 0.01 versus control (d)

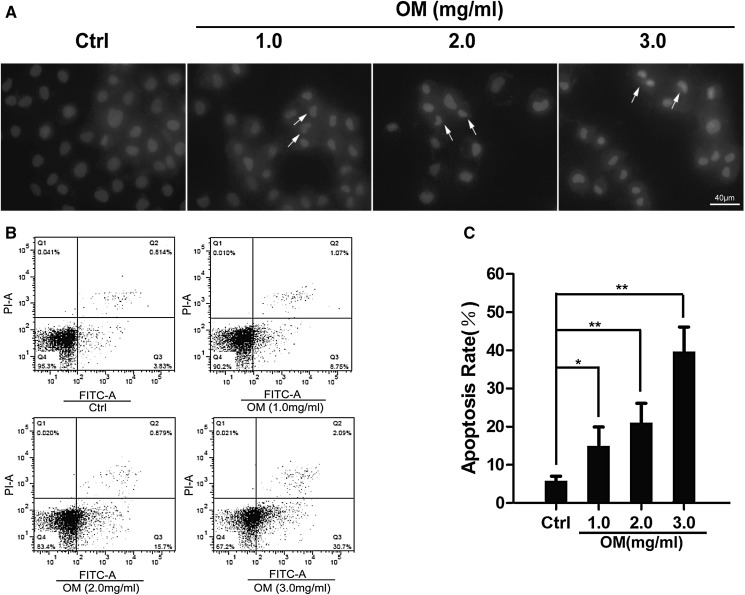

OM induces the apoptosis of GBC–SD cells

We further investigated the pro-apoptotic effect of OM by Hoechst 33342 staining and Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining and FCM methods. The OM-treated GBC–SD cells exhibited strong blue fluorescence and cell nuclei appeared to be highly condensed, while cells in the control group exhibited uniform blue chromatin with organized structure (Fig. 3a). This was confirmed by flow cytometry assay. As shown in Fig. 3b, c, after treatment with OM (0, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h, the apoptotic rates of GBC–SD cells were 14.96 ± 4.96, 21.14 ± 4.95 and 39.66 ± 6.47%, respectively, significantly higher than that of the control group (5.87 ± 1.15%, P < 0.05). These data suggested that OM induced apoptosis in GBC–SD cells dose-dependently.

Fig. 3.

OM induced apoptosis of GBC–SD cells. a GBC–SD cells were treated with OM (0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h. Then, the cells were stained by Hoechst 33342 and observed with fluorescence microscope (×200). Arrows are pointing to the representative cells. For which (exhibited strong blue fluorescence and cell nuclei appeared to be highly condensed). b Cells were treated with OM (0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 mg/mL) for 48 h, and then examined by flow cytometry. c Data are presented as mean ± SD, and each experiment was carried out in triplicate (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. control). Scale bars indicate 40 µm

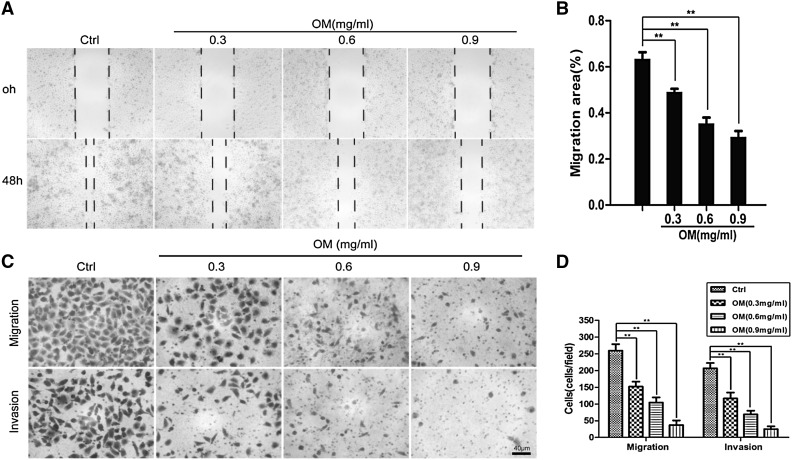

OM inhibits the motility of GBC–SD cells

Invasion and migration play an important role in the complicated process of metastasis of cancer cells. Therefore, wound healing assay and transwell chamber assay were carried out to evaluate the effect of OM on the metastatic potential of GBC–SD cells. Our results indicated that OM could depress the invasive and migratory capabilities of GBC–SD cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). Moreover, OM at these concentrations (0, 0.3, 0.6 and 0.9 mg/mL) did not significantly reduce the viability of GBC–SD cells, which suggested that the inhibition of GBC–SD cells migration and invasion by OM was not the result from a reduction of cell viability.

Fig. 4.

OM inhibited the migration and invasion capabilities of GBC–SD cells. a GBC–SD cells were wounded and then treated with OM (0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9 mg/mL) for 48 h. Pictures were taken at 0 and 48 h (×40). b The migration rate were expressed as a percentage of the control (0 h). c Microphotographs of metastatic and invasive GBC–SD cells(×200). d The number of metastatic and invasive cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and each experiment was carried out in triplicate (**P < 0.01 vs. control group). Scale bars indicate 40 µm

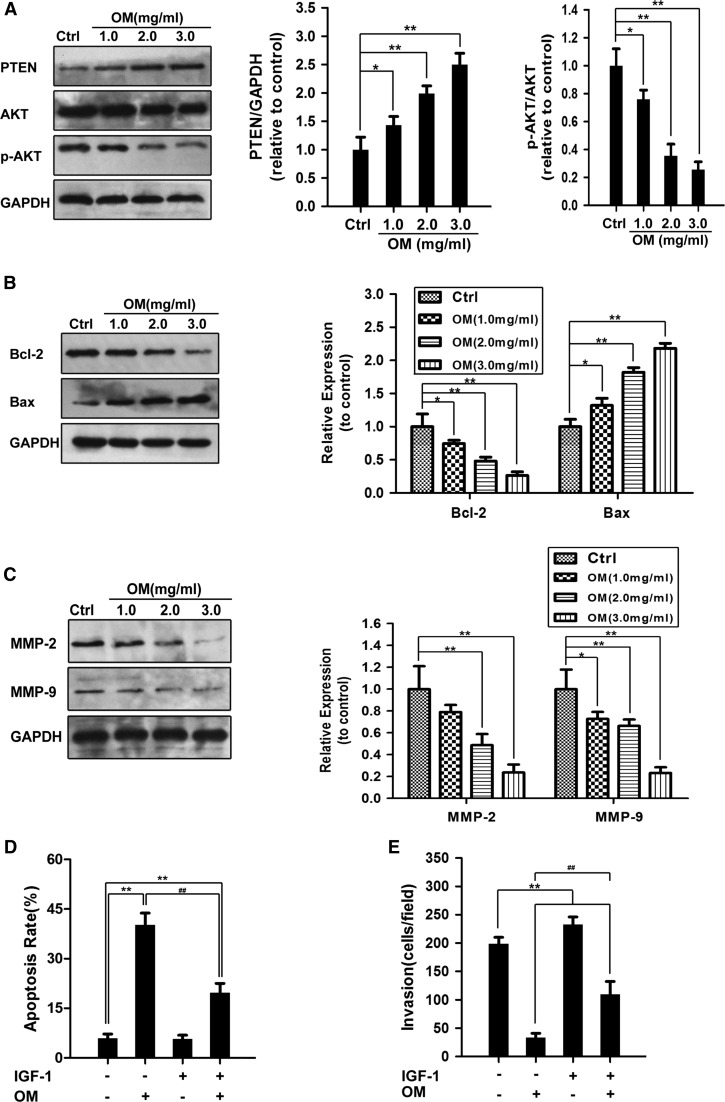

OM suppressed GBC–SD cells proliferation and invasion by regulating the PTEN/AKT pathway

PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway plays an important role in the proliferation and invasion of cancer cells, and AKT is considered as the central mediator of the PI3K/AKT pathway (Zhang et al. 2012). It was found that matrine and oxymatrine can target the AKT signaling pathway and exhibit inhibitory effects on many cancer cells (Liu et al. 2014). Therefore, the changes of the expression of p-AKT were assessed by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 5a, treatment with OM reduced the expression of p-AKT, but did not affect the expression of total AKT. Then, we checked the changes of PTEN, which is the upstream factor of AKT. The result showed that OM could cause an up-regulation of PTEN, which may be one of the reasons of OM-mediated decrease of p-AKT (Fig. 5a). Thereafter, it was confirmed by IGF-1, an activator of PI3K/AKT pathway. One hundred nanograms per milliliter of IGF-1 partially decreased the inhibitive effect of OM on GBC–SD cells (Fig. 5d, e). These observations suggested that OM inhibiting the invasion and inducing apoptosis in GBC–SD cells may function through PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

OM suppressed PTEN/AKT pathway in GBC–SD cells. a–c GBC–SD cells were treated with OM at concentrations of 0, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 mg/mL for 48 h, then the expression of the indicated factors was examined by Western blot. GAPDH was used as the sample loading control. The expression of p-AKT was analyzed by densitometry normalized with the corresponding total AKT with the ratios of p-AKT/AKT. d Effects of IGF-1 on OM-induced apoptosis detected by Annexin V-FITC binding and PI staining method. GBC–SD cells were treated with OM (3.0 mg/mL) in the presence or absence of IGF-1 (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. e IGF-1 decreased the inhibitory effect of OM on GBC–SD cells. Transwell assay of GBC–SD cells treated with OM (0.9 mg/mL) in the presence or absence of IGF-1 (100 ng/mL) for 48 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and each experiment was carried out in triplicate (*P < 0.0; **P < 0.01 vs. the control group; ## P < 0.01, vs. the OM-only group)

Furthermore, to further reveal how OM induces apoptosis, Bcl-2 family proteins were investigated, which plays an important role in cell apoptosis. Our results showed that the expression of Bax was up-regulated, and the level of Bcl-2 was down-regulated in OM-treated GBC–SD cells (Fig. 5b). Therefore, we concluded that the increase in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio was correlated with the OM-induced apoptosis in GBC–SD cells. In addition, MMPs are crucial to cell migration and invasion, thus, the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 was assessed by western blot. As illustrated in Fig. 5c, the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 treated with different concentrations of OM were suppressed in dose-dependent manners compared with the control group.

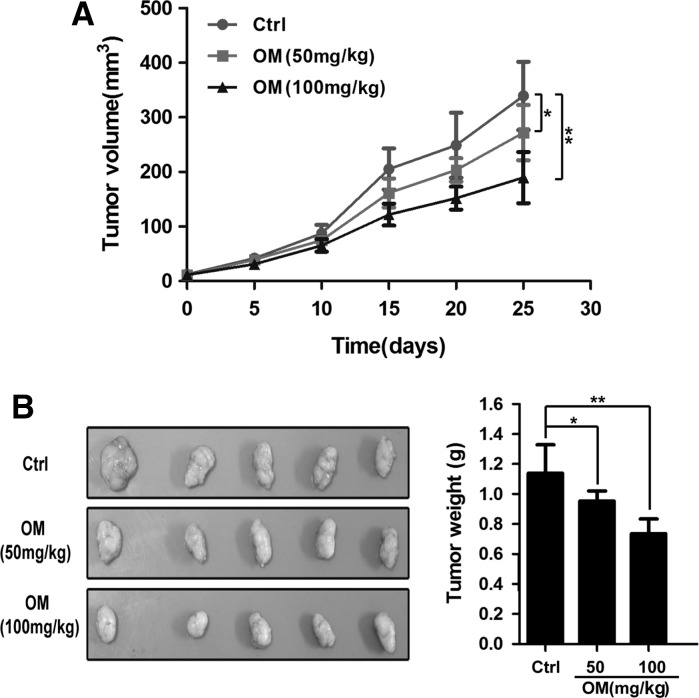

OM inhibited the growth of GBC–SD xenografts in nude mice

To further evaluate the effects of OM on tumor growth in vivo, GBC–SD cells were xenografted into nude mice. As shown in Fig. 6, the volume and weight of xenograft tumors were significantly inhibited in the OM-treated groups compared with the negative control group. The inhibition rates were 16.29 and 35.35%, respectively, and their differences are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

OM inhibited the growth of GBC–SD xenograft tumors in nude mice. a GBC–SD cells were implanted subcutaneously into nude mice, and mice were treated with either OM (50, 100 mg/kg) or control (sterile physiological saline). After treatment, all mice were examined and the tumor volume was measured and compared. b After finishing administrations, the tumors were harvested and weighed. Data are presented as mean ± SD (*P < 0.05 vs. control group, **P < 0.01)

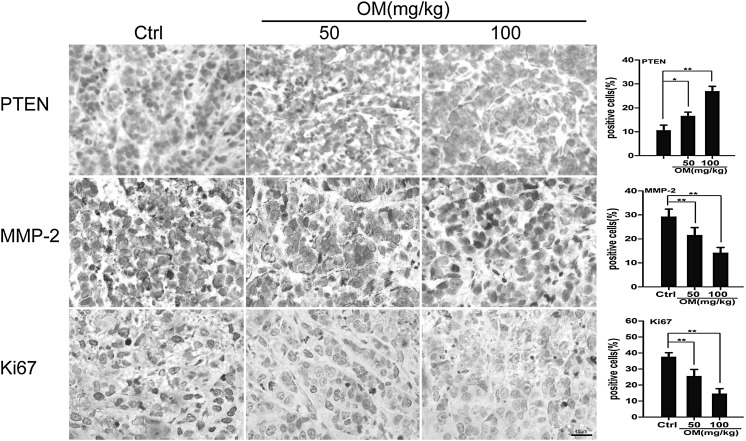

Furthermore, the xenograft tumor tissues were examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. The expression levels of PTEN, MMP-2 and Ki67 in OM-treated tumors were examined. As shown in Fig. 7, the expression of MMP-2 and Ki67 was down-regulated, while the level of PTEN was up-regulated in the OM-treated groups.

Fig. 7.

IHC staining of PTEN, MMP-2 and Ki-67 in xenograft tumors. The expression of PTEN, MMP-2 and Ki67 in xenograft tumors was analyzed by immunohistochemistry (×400). Their expression levels were quantified in percentages of positive cells within five fields under microscope. Data are presented as mean ± SD (*P < 0.05 vs. control group, **P < 0.01). Scale bars indicate 40 µm

Discussion

Recently, an increasing number of studies have revealed that OM exhibited various pharmacological activities and anti-tumor activities, and could be used as alternative treatment for various cancers (Ho et al. 2009). However, to the best of our knowledge, the anti-proliferation and anti-metastatic effect on GBC cells, as well as the underlying mechanisms, have not been previously reported. In this study, we have shown the biochemical and molecular mechanisms of apoptosis induction by and antimetastatic potential of OM in GBC–SD cells.

Apoptosis is a vitally regulated cell suicide process, which plays an important role in the maintenance and development of tissue homeostasis (Xie et al. 2014). In regard to uncontrolled proliferation of tumor cells, one of the important properties of anti-tumor drugs is thought to be successful apoptosis induction (Plati et al. 2011). The induction of apoptosis seems to be a standard and the best strategy in anti-tumor therapy (Yang et al. 2014). In addition, cancer metastasis is a complicated and multi-step process, which is a major cause of cancer-related death, depending on the migration and invasion of cancer cells (Zhang et al. 2009). Metastasis is one of the most important reasons of cancer-related death among the GBC patients (Yun and Kim 2013). Therefore, an agent which can efficiently inhibit the tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and induce cell apoptosis will be a hopeful candidate to suppress cancer growth and metastasis and thus reduce cancer-related mortality.

The proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells are a complicated process with involvement of a series of signaling pathways (Wang et al. 2011a, b). In order to elucidate the molecular mechanisms about how OM induced apoptosis and suppressed the migration and invasion of GBC–SD cells, we investigated several related proteins in OM-treated GBC–SD cells. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which is overactive in many cancers, plays an important role in the tumor cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis and migration (Garcia-Echeverria and Sellers 2008). Blockage of the PI3K/AKT pathway results in programmed cell death and growth inhibition of cancer cells (Liu et al. 2013a, b). As the major downstream kinase of PI3K, p-AKT was down-regulated in a dose-depended manner when GBC–SD cells were treated with OM. Many studies demonstrated that PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT pathway (Gan and Zhang 2009). Activation of PTEN may lead to down-regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Combining the results obtained from the treatments of GBC–SD cells with OM and IGF-1, it was further verified that the inhibitory effect of OM can be attributed, at least partially to AKT inactivation.

In order to further clarify its underlying mechanism, the related downstream proteins of PI3K/AKT pathways were checked. In most cells, apoptosis of cancer cells in response to cytotoxic agents needs an intact mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, and the Bcl-2 family members, Bax and Bcl-2, serve as critical regulators of the mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway (Hale et al. 1996). Bcl-2 that negatively regulates apoptosis promotes cell survival, whereas Bax that positively regulates apoptosis stimulates mitochondrial damage (Bagci et al. 2006). The occurrence and severity of apoptosis depend on the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax (Orrenius 2006). From our data, it may be concluded that OM induced GBC–SD cell apoptosis by activating the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway. Besides cell proliferation, invasion and migration are also two of the most important behaviors of malignant cells. MMPs are highly associated with the progression and development of cancers (Chambers and Matrisian 1997). It has been demonstrated that the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were correlated with lymph node metastasis, invasion and vessel permeation (Tanioka et al. 2004; Shima et al. 1992). Moreover, previous studies found that the AKT signaling pathway was associated with the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in cancerous and healthy tissues (Chen et al. 2013a, b; Jin et al. 2008). Taken together, our results proved that OM inhibited the proliferation, migration, and invasion, and induced the apoptosis of GBC–SD cells, and the underlying mechanism was likely associated with PTEN/PI3K/AKT and its downstream signaling pathways.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated the inhibitory effects of OM on the proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastatic abilities of GBC–SD cells. The underlying mechanisms was involved in regulating of PTEN/PI3K/AKT and its downstream signaling pathways. Although these results warranted further testing, the present findings of OM in GBC–SD cells indicated that OM could be recognized as a novel useful chemotherapeutic agent candidate against GBC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Program for integrative medicine of Suzhou City (No. SYSD2015163).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Liqiang Qian and Xiaqin Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Quangen Gao, Email: wjyyqgg@sohu.com.

Genhai Shen, Email: qianliqiang77@163.com.

References

- Abahssain H, Afchain P, Meals N, Ismaili N, Rahali R, Rabit HM, Errihani H. Chemotherapy in gallbladder carcinoma. Presse Med. 2010;39:1238–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- And DJN, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagci EZ, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR, Ermentrout GB, Bahar I. Bistability in apoptosis: roles of bax, bcl-2, and mitochondrial permeability transition pores. Biophys J. 2006;90:1546–1559. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutros C, Gary M, Baldwin K, Somasundar P. Gallbladder cancer: past, present and an uncertain future. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MS. ChemInform abstract: natural products to drugs: natural product derived compounds in clinical trials. Cheminform. 2008;39:162–195. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YG, Jing S, Li L, Gao JQ, Shen ZY, Liu Y, Xing Y, Wu ML, Wang Y, Xu CQ, Sun HL. Antiarrhythmic effects and ionic mechanisms of oxymatrine from Sophora flavescens. Phytother Res. 2010;24:1844–1849. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai NL, Fu Q, Shi H, Cai CH, Wan J, Xu SP, Wu BY. Oxymatrine liposome attenuates hepatic fibrosis via targeting hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4199–4206. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers AF, Matrisian LM. Changing views of the role of matrix metalloproteinases in metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1260–1270. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.17.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang J, Luo J, Lai F, Wang Z, Tong H, Lu D, Bu H, Zhang R, Lin S. Antiangiogenic effects of oxymatrine on pancreatic cancer by inhibition of the NF-kappaB-mediated VEGF signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:589–595. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, Huang X, Wang Q, Huang JQ, Zhang L, Chen XL, Lei J, Cheng ZX. Sonic hedgehog signaling pathway induces cell migration and invasion through focal adhesion kinase/AKT signaling-mediated activation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 in liver cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:10–19. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai ZJ, Gao J, Wu WY, Wang XJ, Li ZF, Kang HF, Liu XX, Ma XB. Effect of matrine injections on invasion and metastasis of gastric carcinoma SGC-7901 cells in vitro. Zhong Yao Cai. 2007;30:815–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan YH, Zhang S. PTEN/AKT pathway involved in histone deacetylases inhibitor induced cell growth inhibition and apoptosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:e150–e154. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.05.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Echeverria C, Sellers W. Drug discovery approaches targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5511–5526. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu XB, Yang XJ, Hua Z, Lu ZH, Zhang B, Zhu YF, Wu HY, Jiang YM, Chen HK, Pei H. Effect of oxymatrine on specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte surface programmed death receptor-1 expression in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Chin Med J. 2012;125:1434–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B, Zhang T, Su J, Wang K, Lin X. Oxymatrine targets EGFR p-Tyr845, and inhibits EGFR-related signaling pathways to suppress the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;75:353–363. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2651-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale AJ, Smith CA, Sutherland LC. Apoptosis: molecular regulation of cell death. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho JW, Hon PN, Chim WO. Effects of oxymatrine from Ku Shen on cancer cells. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:823–826. doi: 10.2174/187152009789124673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Li S, Gong W, Ding J, Fang C, Quan Z. Mda-7/IL-24 induces apoptosis in human GBC–SD gallbladder carcinoma cells via mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin UH, Suh SJ, Chang HW, Son JK, Lee SH, Son KH, Chang YC, Kim CH. Tanshinone IIA from Salvia miltiorrhiza BUNGE inhibits human aortic smooth muscle cell migration and MMP-9 activity through AKT signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:15–26. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Toledano MB, Taylor-Robinson SD. Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. HPB. 2008;10:77–82. doi: 10.1080/13651820801992641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao Y. Clinical study on effect of matrine injection to protect the liver function for patients with primary hepatic carcinoma after trans-artery chemo-embolization (TAE) Zhong Yao Cai. 2005;28:637–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Shen J, Wu X, Zhang B, Zhang R, Weng H, Ding Q, Tan Z, Gao G, Mu J, Yang J, Shu Y, Bao R, Ding Q, Wu W, Cao Y, Liu Y. Downregulated expression of hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) reduces gallbladder cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Med Oncol. 2013;30:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0587-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jiang K, Zhao F. Oxymatrine suppresses proliferation and facilitates apoptosis of human ovarian cancer cells through upregulating microRNA-29b and downregulating matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:145–151. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, He Y, Liang Y, Wen L, Zhu Y, Wu Y, Zhao LX, Li YS, Mao XL, Liu HY. PI3-kinase inhibition synergistically promoted the anti-tumor effect of lupeol in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:1223–1227. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TY, Tan ZJ, Jiang L, Gu JF, Wu XS, Cao Y, Li ML, Wu KJ, Liu YB. Curcumin induces apoptosis in gallbladder carcinoma cell line GBC–SD cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xu Y, Ji WD. Anti-tumor activities of matrine and oxymatrine: literature review. Tumour Biol. 2014;3:5111–5119. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1680-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Jarnagin WR. Gallbladder carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.07.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius S. Mitochondrial regulation of apoptotic cell death. Toxicol Lett. 2006;149:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Chai H, Kinghorn AD. The continuing search for antitumor agents from higher plants. Phytochem Lett. 2010;3:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plati J, Bucur O, Khosravi-Far R. Apoptotic cell signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011;3:279–296. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00144a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Yin J, Zhang H. Effects of oxymatrine on proliferation of HepG2 cells. China J Chin Mater Med. 2009;34:1426–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Q. The recent effect of radiotherapy combined with compound kushen injection for esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;99:S372–S373. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(11)71109-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Dwary AD, Mohanti BK, Deo SV, Pal S, Sreenivas V, Raina V, Shukla NK, Thulkar S, Garg P, Chaudhary SP. Best supportive care compared with chemotherapy for unresectable gall bladder cancer: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4581–4586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima I, Sasaguri Y, Kusukawa J, Yamana H, Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Morimatsu M. Production of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and metalloproteinase-3 related to malignant behavior of esophageal carcinoma. A Clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1992;70:2747–2753. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921215)70:12<2747::AID-CNCR2820701204>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MQ, Zhu JS, Chen JL, Wang L, Da W, Li Zhu, Zhang WP. Synergistic effect of oxymatrine and angiogenesis inhibitor NM-3 on modulating apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1788–1793. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Cao H, Sun L, Dong S, Bian Y, Han J, Zhang L, Ren S, Hu Y, Liu C, Xu L, Liu P. Antitumor activities of kushen: literature review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:373219. doi: 10.1155/2012/373219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Ma W, Gao Y, Zheng W, Zhang B, Peng Y. Meta-analysis: therapeutic effect of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with compound kushen injection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2012;9:178–188. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v9i2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Zhang S, Li M, Wu X, Weng H, Ding Q, Cao Y, Bao R, Shu Y, Mu J, Ding Q, Wu W, Yang J, Zhang L, Liu Y. Regulation of cell proliferation and migration in gallbladder cancer by zinc finger X-chromosomal protein. Gene. 2013;528:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanioka Y, Yoshida T, Yagawa T, Saiki Y, Takeo S, Harada T, Okazawa T, Yanai H, Okita K. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 and Matrix metalloproteinase-9 are associated with unfavourable prognosis in superfical oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;89:2116–2121. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeriote F, Corbett T, Lorusso P, Moore RE, Scheuer P, Patterson G. Anticancer agents from natural products. Pharm Biol. 2015;33:59–66. doi: 10.3109/13880209509067088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YP, Zhao W, Xue R, Zhou ZX, Liu F, Han YX, Ren G, Peng ZG, Cen S, Chen HS, Li YH, Jiang JD. Oxymatrine inhibits hepatitis B infection with an advantage of overcoming drug-resistance. Antivir Res. 2011;89:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yu S, Shi W, Ge L, Yu X, Fan J, Zhang J. Curcumin inhibits the migration and invasion of mouse hepatoma Hca-F cells through down-regulating caveolin-1 expression and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:775–782. doi: 10.1002/iub.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M, Yi X, Wang RJ, Zhu M, Qi C, Liu Y, Ye Y, Tan S, Tang A. 14-thienyl methylene matrine (YYJ18), the derivative from matrine, induces apoptosis of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by targeting MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways in vitro. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33:1475–1483. doi: 10.1159/000358712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Yang L, Tian WC, Li J, Liu J, Zhu M, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Liu F, Zhang Q, Liu Q, Shen Y, Qi Z. Resveratrol plays dual roles in pancreatic cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:749–755. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun SJ, Kim WJ. Role of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in bladder cancer: from prognosis to therapeutic target. Korean J Urol. 2013;54:645–650. doi: 10.4111/kju.2013.54.10.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang H, Yu P, Liu Q, Liu K, Duan HY, Luan GL, Yagasaki K, Zhang GY. Effects of matrine against the growth of human lung cancer and hepatoma cells as well as lung cancer cell migration. Cytotechnology. 2009;59:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10616-009-9211-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Zhang Y, Zhuang Y, Wang J, Ye J, Zhang S, Wu JB, Yu K, Han YX. Matrine induces apoptosis in human acute myeloid leukemia cells via the mitochondrial pathway and Akt inactivation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]