Abstract

Background

Hospitalization over the last one year, an indicator of health service utilization, is an important and costly resource in older adult care. However, data on the relationship between functional status and annual hospitalization among older Chinese people are sparse, particularly for those with and without multimorbidity. In this study,we aimed to examine the association between functional status and annual hospitalization among community-dwelling older adults in Southern China, and to explore the independent contributions of socio-demographic variables, lifestyle and health-related factors and functional status to hospitalization in multimorbid and non-multimorbid groups.

Methods

This cross-sectional, community-based survey, studied 2603 older adults aged 60 years and above. Functional status was assessed by Functional Independence Measure (FIM). The outcome variable was any hospitalization over the last one year (annual hospitalization). Clustered logistic regression was used to analyze the independent contributions of FIM domains to annual hospitalization.

Results

Only in the multimorbid group, did the risk of annual hospitalization decrease significantly with increasing FIM score in walk domain (adjusted OR = 0.80 per SD increase, 95% CI = 0.70–0.91, P = 0.001) and its independent contribution accounted for 24.62%, more than that of socio-demographic variables (18.46%). However, among individuals without multimorbidity, there were no significant associations between FIM domains and annual hospitalization; thus, no independent contribution to the risk of hospitalization was observed.

Conclusions

There exist some degree of correlation between functional status and annual hospitalization among older adults in Southern China, which might be due to the presence of multimorbidity with advanced age.

Keywords: Hospitalization, Functional status, Multimorbidity, Older adults, Cross-sectional study, China

Background

The population of China is aging much faster than those of other high-income or low- and middle-income countries, with the proportion of the population aged 60 years and over is predicted to increase from 12.4% in 2010 to 28% in 2040 [1], which has become a major concern. Aging is strongly associated with increased multiple chronic conditions [2, 3] and functional decline [4], which in turn leads to substantial increases in health resources usage and costs [5–8]. Hospitalization in the last year, as a part of health service utilization, is an important and costly resource in older adult care. Numerous studies have examined the determinants of hospitalization, including, age, gender [9], multiple chronic conditions [5, 10, 11], and activities of daily living (ADL) limitations [12]. Several studies also have found that hospitalization, especially if repeated and prolonged, might be associated with negative consequences including an increased risk of falls [13], worsening or irreversible functional decline [13–15], and death [16]. To reduce hospitalization and its associated adverse outcomes, it is important to identify and understand the risk factors of hospitalization in older adults.

Among community-dwelling individuals, the ability to take care of themselves or survive in the community is an important aspect of quality of life. The Functional Independence Measure is one of the instruments to measure functional status [17]. Generally, loss of function is related to advancing age. Many of the very old lose their ability to live independently owing to limited mobility, frailty or other physical or mental health problems, which consequently require additional health services, particularly unplanned hospitalization. Multimorbidity (≥2 chronic diseases) is common in older adults. There have been many studies exploring the correlations of multimorbidity, functional status [18–20] and hospitalization [21, 22]. A population-based study in Brazil showed that disability was strongly associated with hospitalization, yet it also suggested that functional health dimensions have not oriented health services, still largely conditioned on the presence of diseases [23]. Moreover, Mor V and colleagues [24] documented the link between functional decline and increased hospital use. However, they also indicated that the “true” causes of hospitalization are less clear as functional status is likely affected by multiple chronic diseases and age-related processes. Unfortunately, the issue was simply mentioned and failed to be deeply studied. Therefore, exploring the association of functional status and hospitalization based on multimorbidity stratification is important and necessary.

With the rapid aging of population in China, the health of older adults has been deeply concerned. Thus, in this study, we selected the community-dwelling older adults in Southern China and examined the association between functional status and annual hospitalization, to explore the independent contributions of socio-demographic variables, lifestyle and health-related factors and functional status to hospitalization in multimorbid and non-multimorbid groups.

Methods

Study design and populations

The data were based on a cross-sectional community health diagnosis survey in a district of Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China, 2015. The survey samples were selected using a multistage sampling method of family members drawn from 5 % of the total populations in this region. The primary sampling units were street communities, second-stage sampling units were communities and the stratification was according to the economic level. All information were obtained by face to face interviews in residents’ homes. The sample size was decided according to the hospitalization rate and calculated by the formula of sample size for rate. Supposing that the hospitalization rate was 15% according to the results of pre-survey, the sample size of this study was sufficient based on the community health diagnosis survey. This study selected available information from participants over the age of 60 years. Of 2919 participants, 316 provided incomplete questionnaire data and the response rate was 89.2%. Finally, data from a total of 2603 older adults were included in our final analysis.

Measurements and instruments

Participant characteristics

We firstly conducted a literature search to identify the potential factors related to annual hospitalization in older adults. This search yielded the following variables: age, gender, marital status, employment status, smoking, physical activities, body mass index, chronic conditions, functional status [5–7, 9, 10, 23–26]. Therefore the variables in this study analysis included socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, marital status, etc), lifestyle and health-related factors (smoking, physical activities, etc), functional status and hospitalization over the last one year. Current smoking status was defined as smoking one or more cigarettes per day for at least six months. Drinking was defined as the consumption of at least thirty-seven milliliter of alcohol per week. Exercise was assessed by the responses to the question: “How many times do you exercise every week? (more than three times/week, one to two times/week and no exercise)”. The BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2). Information on annual hospitalization was obtained by the responses to the question: “Have you been hospitalized in the last year? (yes/no)” .

Assessment of functional status

Functional status was assessed using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM). The FIM score was defined as the level of assistance required for an individual to perform ADL, which indicated the burden of caring for them [27]. The tool includes two parts (motor function and cognition function), six domains and 18 items. Among six domains, self-care ability has six items, including eating, grooming, bathing, upper body dressing, lower body dressing and toileting. Sphincter control includes bladder management and bowel management. Transfer includes bed to chair transfer, toilet transfer and shower transfer. Walk domain includes locomotion and stairs. Communication includes cognitive comprehension and expression. Social cognition includes social interaction, problem solving and memory. Each item is scored from 1 to 7 based on the level of independence, where 1 represents total assistance (patient can perform less than 25% of the task or requires more than one person to assist) and 7 indicates complete independence [28]. Possible scores range from 18 to 126, with lower scores indicating less functional independence. Functional status can be divided into functional dependence (< 108 scores) and functional independence (108–126 scores). As we know, the 18-item FIM instrument has been reported to be reliable and well validated [29–31] and can be widely used in China [32].

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more chronic diseases in an individual [33]. The number of chronic diseases was self-reported based on the responses to the question, “Has a doctor ever diagnosed that you had…(yes/no)” [34]. The chronic diseases investigated in this study included: hypertension, chronic pain, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, bone diseases, chronic gastrointestinal diseases, heart disease, gout, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, spleen and gallbladder diseases, pulmonary disease, stroke, cancer, multiple sclerosis, dementia and mental disorder.

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations (SD) were presented for continuous variables, while frequency and percentage were used for categorical variables. The main dichotomous outcome variable was annual hospitalization. To evaluate the differences in the distributions of multimorbidity by continuous or categorical variables, we used t-tests or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Logistic regression was employed to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for the associations between FIM six domains and annual hospitalization. During the regression analysis, continuous variables (including age, BMI, number of chronic diseases and FIM domains scores) were standardized in order to make the data comparable.

Subsequently, clustered logistic regression [35, 36] was used to explore the impacts of socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle and health-related factors and FIM domains (three clusters based on the nature of the study variables) on annual hospitalization. Multidirectional associations may exist among three clusters and the dependent variable. To be specific, cluster 1 may impact cluster 2, cluster 3 and the outcome variable. Likewise, cluster 2 may affect cluster 3 and the dependent variable, while cluster 3 may impact the outcome variable. Consequently, simultaneous consideration of variables from the clusters in a free multiple regression model (i.e. a free forward stepwise logistic regression model) might bring about confounded inference. Thus, clustered logistic regression [35] was adopted to analyze whether the addition of FIM variables to the models including socio-demographic and lifestyle and health-related variables could significantly increase the explanatory power of the risk adjustment models. The final regression model was determined in three steps: (1) A forward stepwise regression of annual hospitalization for the cluster 1 variables; (2) A forward stepwise regression for the cluster 2 variables with the equation derived from step 1 as a fixed part of the new regression model; (3) A forward stepwise regression for the cluster 3 variables with the equation derived from step 2 as a fixed part of the new regression model. Variables include and exclude criteria for the stepwise regression models were P values of 0.05 and 0.10, respectively.

The independent effect of each cluster was assessed by the corresponding R2 value. The independent contribution share of each cluster was calculated as individual R2 change / total R2 change in the final model × 100%. The R2 in logistic regression models was the Nagelkerke “pseudo” R2, similar to the classical R2 in linear regression models for data interpretation [36].

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two-tailed P values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 2603 older adults (aged 60 years and above), with an average age of (69.28 ± 7.59) years, the majority were women (57.90%), married (76.80%), and unemployed (95.00%). More than half of the subjects had an education level of primary school or lower. Regarding lifestyle and health-related factors, most did not smoke (86.50%), drink (85.50%), and exercised more than three times per week (60.30%). The average BMI was (23.90 ± 3.87) kg/m2. The most frequent chronic diseases included hypertension, chronic pain, diabetes mellitus and so on. About 45.06% of older adults reported multimorbidity. The FIM scores in six domains varied from 19.82 ± 3.02 to 41.14 ± 4.02. Among the six FIM domains, walk scored the lowest, while self-care ability scored the highest. The prevalence of annual hospitalization was 10.50% and was significantly higher in the multimorbid group (P < 0.001). More details of participants’ characteristics among participants with and without multimorbidity are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Variables and assignments

| Variable | Assignment |

|---|---|

| Cluster1: socio-demographic factors | |

| Age (years) | |

| Gender | 1 = Male, 2 = Female |

| Marital status | 1 = Married, 2 = Single |

| Education level | 1 = Primary school or lower, 2 = Middle school, 3 = High school or above |

| Employment status | 1 = Employed, 2 = Unemployed |

| Individual economic condition | 1 = Good, 2 = Not good |

| Medical insurance | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| Cluster2: lifestyle and health-related factors | |

| Smoking | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| Drinking | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| Physical exercise | 1 = Over 3 times/week, 2 = 1–2 times/week, 3 = Take no exercise |

| Body mass index | |

| Sleep status | 1 = Good, 2 = Not good |

| History of chronic diseases a | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| Absolute number of chronic diseases | |

| Cluster3: FIM domains | |

| Self-care ability | |

| Sphincter control | |

| Transfer | |

| Walk | |

| Communication | |

| Social cognition | |

| Outcome | |

| Hospitalization in the last year | 0 = No, 1 = Yes |

FIM Functional Independence Measure

Single: unmarried, divorced and widowed. Multimorbidity was defined as the presence of two or more chronic diseases in an individual

aHistory of chronic diseases, including hypertension, chronic pain, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, bone diseases, chronic gastrointestinal diseases, heart disease, gout, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, spleen and gallbladder diseases, pulmonary disease, stroke, cancer, multiple sclerosis, dementia, and mental disorder

Table 2.

Study participant characteristics stratified by multimorbidity

| Variable | Multimorbid (n = 1173) |

Non-multimorbid (n = 1430) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic factors | |||

| Age (years) | 70.08 (7.7) | 68.62 (7.4) | < 0.001a |

| Gender (male) | 448 (38.2) | 647 (45.2) | < 0.001b |

| Marital status (married) | 840 (71.6) | 1158 (81.0) | < 0.001b |

| Education level | 0.044b | ||

| Primary school or lower | 587 (50.0) | 756 (52.9) | |

| Middle school | 249 (21.2) | 325 (22.7) | |

| High school or above | 337 (28.7) | 349 (24.4) | |

| Employment status (yes) | 38 (3.2) | 92 (6.4) | < 0.001b |

| Economic condition (good) | 627 (53.5) | 796 (55.7) | 0.029b |

| Medical insurance (yes) | 1158 (98.7) | 1415 (99.0) | 0.058b |

| Lifestyle and health-related factors | |||

| Smoking (yes) | 143 (12.2) | 208 (14.5) | 0.080b |

| Drinking (yes) | 171 (14.6) | 206 (14.4) | 0.901b |

| Exercise | 0.006b | ||

| Over 3 times/week | 716 (61.0) | 854 (59.7) | |

| 1–2 times/week | 302 (25.7) | 325 (22.7) | |

| Take no exercise | 155 (13.2) | 251 (17.6) | |

| Body mass index score | 24.19 (4.1) | 23.66 (3.6) | 0.001a |

| Sleep status (good) | 579 (49.4) | 894 (62.5) | < 0.001b |

| Hypertension (yes) | 808 (68.9) | 360 (25.3) | < 0.001b |

| Chronic pain (yes) | 574 (48.9) | 128 (9.0) | < 0.001b |

| Diabetes mellitus (yes) | 352 (30.0) | 88 (6.2) | < 0.001b |

| Hyperlipidemia (yes) | 330 (28.1) | 30 (2.1) | < 0.001b |

| Bone diseases (yes) | 289 (24.6) | 40 (2.8) | < 0.001b |

| Chronic gastrointestinal diseases (yes) | 261 (22.3) | 45 (3.1) | < 0.001b |

| Heart disease (yes) | 244 (20.8) | 26 (1.8) | < 0.001b |

| Gout (yes) | 167 (14.2) | 15 (1.0) | < 0.001b |

| Peripheral vascular disease (yes) | 138 (11.8) | 12 (0.8) | < 0.001b |

| Chronic kidney disease (yes) | 104 (8.9) | 10 (0.7) | < 0.001b |

| Spleen and gallbladder diseases (yes) | 94 (8.0) | 10 (0.7) | < 0.001b |

| Pulmonary disease (yes) | 89 (7.6) | 10 (0.7) | < 0.001b |

| Stroke (yes) | 71 (6.1) | 6 (0.4) | < 0.001b |

| Cancer (yes) | 23 (2.0) | 4 (0.3) | < 0.001b |

| Multiple sclerosis (yes) | 17 (1.4) | 2 (0.1) | < 0.001b |

| Dementia (yes) | 16 (1.4) | 1 (0.1) | < 0.001b |

| Mental disorder (yes) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 0.419b |

| Number of chronic diseases | 3.05 (1.4) | 0.55 (0.5) | < 0.001a |

| FIM domains scores | |||

| Self-care ability | 40.87 (4.7) | 41.36 (3.4) | < 0.001a |

| Sphincter control | 13.63 (1.6) | 13.79 (1.2) | < 0.001a |

| Transfer | 19.55 (3.3) | 20.03 (2.7) | < 0.001a |

| Walk | 12.62 (2.5) | 13.12 (2.1) | < 0.001a |

| Communication | 13.00 (2.3) | 13.29 (1.8) | < 0.001a |

| Social cognition | 18.58 (3.3) | 19.29 (2.7) | < 0.001a |

| Outcome | |||

| Annual hospitalization | < 0.001b | ||

| No | 986 (84.1) | 1344 (94.0) | |

| Yes | 187 (15.9) | 86 (6.0) | |

FIM Functional independence measure

Data presented are mean (SD) or n (%); Multimorbidity defined as the presence of two or more of chronic diseases in an individual

aBased on t-test

bBased on chi-square test

Table 3 shows the associations between FIM domains and annual hospitalization among older adults stratified by multimorbidity. In the multimorbid group, higher FIM scores in walk and social cognition domains were significantly associated with lower odds of hospitalization, namely, the risk of hospitalization increased significantly with decreasing FIM scores in walk and social cognition domains. For non-multimorbid subjects, a lower FIM score in walk domain was associated with increased risk of hospitalization.

Table 3.

Associations between FIM domains and annual hospitalization in multimorbid (n = 1173) and non-multimorbid (n = 1430) older adultsa

| Variable | Annual Hospitalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR b | 95% CI | |||||

| Multimorbid | Non-multimorbid | Total | Multimorbid | Non-multimorbid | Total | |

| Self-care ability | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 0.78–1.29 | 0.61–1.72 | 0.84–1.31 |

| Sphincter control | 1.03 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 0.82–1.28 | 0.75–2.16 | 0.85–1.27 |

| Transfer | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.78–1.22 | 0.70–1.24 | 0.81–1.14 |

| Walk | 0.79* | 0.72* | 0.75* | 0.66-0.95 | 0.56-0.94 | 0.64–0.87 |

| Communication | 1.28 | 0.93 | 1.19 | 1.04–1.58 | 0.69–1.24 | 1.00–1.41 |

| Social cognition | 0.78* | 1.06 | 0.81* | 0.63-0.97 | 0.75-1.49 | 0.68–0.97 |

FIM Functional Independence Measure

*P < 0.05

aThe six FIM domains were included as predictor variables for annual hospitalization in a multivariable regression model without adjusting for other variables

bOdds ratio per SD increase in a predictor variable

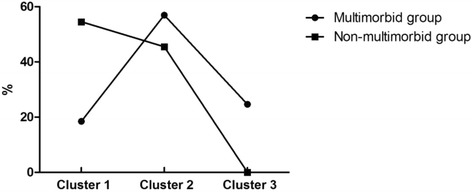

Several clustered logistic regression models are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. The independent contributions of three clusters to annual hospitalization among older adults with and without multimorbidity are illustrated in Fig. 1. Among socio-demographic variables (cluster 1), in the multimorbid group, only gender (male) was significantly associated with hospitalization (P = 0.004), while age had a significant association with annual hospitalization in non-multimorbid participants (P < 0.001). The independent contributions from social demographic variables with multimorbidity stratification were 18.46% and 54.55%, respectively. In cluster 2 (lifestyle and health-related factors), among participants with multimorbidity, the number of chronic diseases was significantly associated with annual hospitalization, while in non-multimorbid group, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease and heart disease are the significant risk factors for annual hospitalization. The independent contributions of the second cluster in older adults with and without multimorbidity were 56.92% and 45.45%, respectively. In the third cluster, the risk of annual hospitalization decreased significantly with increasing FIM score in walk domain (adjusted OR = 0.80 per SD increase, 95% CI = 0.70–0.91, P = 0.001) only in multimorbid group and its independent contribution to hospitalization was 24.62%. However, for those older adults without multimorbidity, there were no associations between all FIM domains and dependent variable; consequently, no independent contribution of the third cluster was observed.

Table 4.

Clustered logistic regression models explaining hospitalization in the last year by socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle and health-related factors, and FIM domains among patients with multimorbidity (n=1173)

| Variablea | OR b | 95% CI | P value | Nagelkerke R2c | Independent contribution d (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| Gender (male) | 1.59 | 1.16–2.17 | 0.004 | ||

| Total | 0.012 | 18.46 | |||

| Model 2 | |||||

| Gender (male) | 1.60 | 1.16–2.20 | 0.004 | ||

| Number of chronic diseases | 1.52 | 1.30–1.78 | < 0.001 | ||

| Total | 0.049 | 56.92 | |||

| Model 3 | |||||

| Gender (male) | 1.63 | 1.18–2.24 | 0.003 | ||

| Number of chronic diseases | 1.45 | 1.24–1.71 | < 0.001 | ||

| Walk | 0.80 | 0.70–0.91 | 0.001 | ||

| Total | 0.065 | 24.62 | |||

aOnly variables with P < 0.05 were included in the model

bFor age, body mass index, number of chronic diseases, and functional independence domains scores, the odd ratios per SD increase are shown

cNagelkerke R2 is the variance of the dependent variable (hospitalization in the last year) explained by all independent variables included in the regression model

dThe independent contribution of each cluster of predictors to the variation in hospitalization in the last year calculated as individual corresponding R2 change/total R2 change in the final model × 100%

Table 5.

Clustered logistic regression models explaining hospitalization in the last year by socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle and health-related factors, and FIM domains among patients without multimorbidity (n = 1430)

| Variablea | ORb | 95% CI | P value | Nagelkerke R2c | Independent contributiond (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| Age | 1.47 | 1.20–1.79 | < 0.001 | ||

| Total | 0.048 | 54.55 | |||

| Model 2 | |||||

| Age | 1.51 | 1.23–1.85 | < 0.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.61 | 1.27–5.35 | 0.009 | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 8.75 | 2.22–34.47 | 0.002 | ||

| Heart disease | 3.93 | 1.42–10.92 | 0.009 | ||

| Total | 0.088 | 45.45 | |||

| Model 3 | |||||

| Age | 1.51 | 1.23–1.85 | < 0.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.61 | 1.27–5.35 | 0.009 | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 8.75 | 2.22–34.47 | 0.002 | ||

| Heart disease | 3.93 | 1.42–10.92 | 0.009 | ||

| Total | 0.088 | 0 | |||

aOnly variables with P < 0.05 were included in the model

bFor age, body mass index, number of chronic diseases, and functional independence domains scores, the odd ratios per SD increase are shown

cNagelkerke R2 is the variance of the dependent variable (hospitalization in the last year) explained by all independent variables included in the regression model

dThe independent contribution of each cluster of predictors to the variation in hospitalization in the last year calculated as individual corresponding R2 change/total R2 change in the final model × 100%

Fig. 1.

The independent contributions of three clusters to annual hospitalization between participates with and without multimorbidity

Additionally, we also performed a chi-square test to analyze the association between FIM category and annual hospitalization among older adults with and without multimorbidity. The results found that functional status was significantly associated with annual hospitalization among participants with multimorbidity, (P = 0.003), whereas there was no association in non-multimorbid group (P > 0.05). The multimorbid participants with functional dependence had a higher rate of hospitalization (25.2% VS 14.8%).

Discussion

Main findings

This study was to explore the association of functional status and hospitalization in multimorbid and non-multimorbid older Chinese adults. The results showed that the risk of annual hospitalization increased with lower scores in certain FIM domains in multimorbid group, and the independent contribution of FIM domains to hospitalization was larger than that of socio-demographic characteristics. Whereas no contribution of FIM domains was observed among non-multimorbid older adults. These findings suggested that the association of functional status on annual hospitalization might be likely due to the presence of multimorbidity with advanced age.

Comparing with previous studies

Our study showed that walk domain of FIM was significantly associated with hospitalization in multimorbid older adults. A higher walk score was associated with lower odds of annual hospitalization after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics and lifestyle and health-related factors. The results were consistent with a US Renal Data System special study [37] that reported that low walk speed was associated with an increased likelihood of ADL difficulty and hospitalization in the geriatric population. Another survey also found that a single disability variable (use of cane, walker, or wheelchair) was a predictor of hospitalization [10]. Many studies have used different methods to measure functional status to demonstrate the relationship between functional status and hospital admissions or readmissions [23, 38, 39]. A population-based study including 1624 elderly patients (≥60 years) found that both ADL and IADL were significantly associated with hospitalization [23]. There was another cohort study to examine the independent association of activity limitation stages with risk of hospitalization within a year in elderly Medicare beneficiaries, showing that the adjusted risk of first hospitalization increased with higher activity limitation stages [38]. Older people’s poor functional independence is not only an important indicator of poor health but also might exacerbate the severity of underlying health problems, resulting in increased hospitalization. Additionally, poor functional independence is associated with higher frequency of accidents, increased risk of falls [40], and multiple chronic diseases. However, unfortunately, most studies neglected the important effect of co-morbidity, which is a common risk for disability and hospitalization. In our study, the important findings were that the walk domain score was significantly associated with hospitalization only in the multimorbid group, whereas no contribution of FIM domains was observed among older adults without multimorbidity. These findings suggest that the increased risk of hospitalization may be conditioned on the presence of multiple chronic diseases, similar to the findings of Fialho [23]. Also, Mor et al. [24] reported that chronic illness is a robust predictor of all future outcome states, even more so than age and nearly as much as function. There was no denying that, when compared to those without multimorbidity, multimorbid individuals mostly have older age and poorer functional ability. Besides, functional ability was influenced by age [41, 42] and the older the age, the lower the scores. With the aging process, the older adults would inevitably experience loss of strength, osteoporosis or other degenerative changes, which might increase the risk of diseases and loss of functional ability, and even lead to hospitalization or death. Anyway, age was an important factor that cannot be ignored. The potential explanation of interaction may be that the combined action of multimorbidty status and poor functional ability further increased the likelihood of hospitalization. On one hand, many studies have demonstrated that a greater number of chronic diseases was consistently associated with greater risk of functional dependency. A recent population-based cohort study in Sweden found that the greater dependence of the elderly adults was from multimorbidity [18]. On the other hand, the pattern of positive associations between multimorbidity and hospital resource utilization has been consistently reported across a range of other studies [21, 22, 43]. There is a considerable variation in health care utilization and costs in individuals with and without multiple chronic conditions [44]. Those multimorbid older adults were admitted to hospitals more often than peers without multimorbidity. This agrees with our results that the relevance of FIM domains on hospitalization were found only in the multimorbid group which might be attributed to the existence of multimorbidity- their common risk factor. In summary, the associations of hospitalization and multiple chronic conditions and functional status are complex and not be fully understand and more studies are needed in the future.

We also found that, in the multimorbid group, the independent contribution of the third cluster to hospitalization was even larger than that of socio-demographic characteristics. It might be partially explained by that individuals with multimorbidity are more likely to seek treatment or to be hosptitalized due to the poor disease-related function rather than the individual characteristics. Of the social demographic factors, only gender was significantly associated with annual hospitalization and men had greater odds of hospitalization, as shown in previous studies [9, 10, 45]. However, no association of age on hospitalization was observed in this population, which was likely because age-related risk factors (such as comorbidities) are significant predictors of hospital admissions [46]. Also, multimorbidity is generally related to advanced age, so variation in age was markedly constrained. Additionally, the second cluster had the greatest independent contribution to the hospitalization and the number of chronic diseases was significantly associated with the hospitalization. The unhealthy lifestyle, as risk factors of chronic diseases, and other illnesses could increses the likelihood of the hospitalization. Therefore, the prevention, control and treatment of chronic diseases are essential and urgent.

In the non-multimorbid, age had a significant association with annual hospitalization, similar to a previous study finding that the probability of hospitalization significantly increased with age among older Germans [7]. Our results also showed that some specific diagnosed diseases were found to be significantly associated with hospitalization. Individuals with diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease and heart disease were at greater risk of hospitalization, in accordance with previous studies [5, 10]. Another survey of 18 countries across five regions also observed that inadequate glycemic control and microvascular complications were independent parameters associated with hospitalization [47].

However, this study has several limitations. First, the data in our analyses were based on self-reports, which could lead to biases or tend to inaccuracies. Second, reasons of hospitalization and the length of hospital stay were not included in our analyses. Future studies are needed to provide more detailed information. Additionally, the larger sample size might overestimate certain parameters. Lastly, this is a cross-sectional study, so that the observed associations could not be assumed to be causal relationships. Further in-depth studies with longitudinal follow-up data are warranted to explore the cause-effect relationship.

Conclusions

A lower FIM score in walk domain was associated with increased risk of annual hospitalization in older Chinese adults with multimorbidity. The findings suggested that there exist some degree of correlation between functional status and annual hospitalization among older adults in Southern China, which might be due to the presence of multimorbidity with advanced age. Tailored interventions for older people may be needed to prevent multimorbidity and improve functional status so as to reduce the risk of hospitalization.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the medical students of Guangzhou Medical University and all staff of the local Community Health Service Agencies, for their kind assistance in data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201607010136) and Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (C2015032).

Availability of data and materials

Data might not be shared directly, because it’s our team work and informed consent should be attained from team members.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activities of daily living

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- FIM

Functional Independence Measure

- OR

Odds ratio

- SD

Standard deviation

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the study framework, interpretation of the results, revisions of drafts of the manuscript, and approved the version submitted for publication. XXW, ZBC and PXW conducted the data analyses. XXW and ZBC drafted the manuscript. XJC, LLH, LYF and XW checked the paper. PXW and XXW finalized the manuscript with inputs from all authors. In addition, in the process of revision, XXW, XJC, LLH and XYS searched project-related knowledge and actively discussed about the comments of the revision.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this survey was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Medical University. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to study entry.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this publication.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiao-Xiao Wang, Email: xiaoxiao52625@163.com.

Zhao-Bin Chen, Email: chenzb.md@vip.163.com.

Xu-Jia Chen, Email: 843606401@qq.com.

Ling-Ling Huang, Email: huanglingling0703@163.com.

Xiao-Yue Song, Email: 18236590620@163.com.

Xiao Wu, Email: 18625832936@163.com.

Li-Ying Fu, Email: 18317856338@163.com.

Pei-Xi Wang, Email: peixi001@163.com.

References

- 1.WHO. China country assessment report on ageing and health. New York; 2015.

- 2.Carvalho JN, Roncalli AG, Cancela MC, Souza DL. Prevalence of multimorbidity in the Brazilian adult population according to socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang HH, Wang JJ, Wong SY, Wong MC, Li FJ, Wang PX, Zhou ZH, Zhu CY, Griffiths SM, Mercer SW. Epidemiology of multimorbidity in China and implications for the healthcare system: cross-sectional survey among 162,464 community household residents in southern China. BMC Med. 2014;12:188. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, de Rooij SE, Grypdonck MF. A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(1):46–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JE, Russell LB, Davis DM, Milan E, Carson JL, Taylor WC. Biomedical risk factors for hospital admission in older adults. Med Care. 1998;36(3):411–421. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199803000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geitona M, Zavras D, Kyriopoulos J. Determinants of healthcare utilization in Greece: implications for decision-making. Eur J Gen Pract. 2007;13(3):144–150. doi: 10.1080/13814780701541340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajek A, Bock JO, König HH. Which factors affect health care use among older Germans results of the German ageing survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-1982-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heider D, Matschinger H, Müller H, Saum KU, Quinzler R, Haefeli WE, Wild B, Lehnert T, Brenner H, König HH. Health care costs in the elderly in Germany: an analysis applying Andersen's behavioral model of health care utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann F, Schmiemann G. Influence of age and sex on hospitalization of nursing home residents: a cross-sectional study from Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2008-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wieland D, Lamb VL, Sutton SR, Boland R, Clark M, Friedman S, Brummel-Smith K, Eleazer GP. Hospitalization in the program of all-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): rates, concomitants, and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(11):1373–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JN, Howard EP, Steel K, Schreiber R, Fries BE, Lipsitz LA, Goldman B. Predicting risk of hospital and emergency department use for home care elderly persons through a secondary analysis of cross-national data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:519. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0519-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kliebsch U, Siebert H, Brenner H. Extent and determinants of hospitalization in a cohort of older disabled people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(3):289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Bingham KW, McCann RM. Hazards of hospitalization: residence prior to admission predicts outcomes. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):537–541. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd CM, Xue QL, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Hospitalization and development of dependence in activities of daily living in a cohort of disabled older women: the Women's health and aging study I. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(7):888–893. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.7.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, Fortinsky RH, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization. JAMA. 2001;285(23):2987–2994. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buurman BM, van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, de Haan RJ, de Rooij SE. Variability in measuring (instrumental) activities of daily living functioning and functional decline in hospitalized older medical patients: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(6):619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzuto D, Melis RJF, Angleman S, Qiu C, Marengoni A. Effect of chronic diseases and multimorbidity on survival and functioning in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1056–1060. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams JS, Eqede LE. The association between multimorbidity and quality of life, health status and functional disability. Am J Med Sci. 2016;352(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jindai K, Nielson CM, Vorderstrasse BA, Quiñones AR. Multimorbidity and Functional Limitations Among Adults 65 or Older, NHANES 2005–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E151. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.160174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agborsangaya CB, Lau D, Lahtinen M, Cooke T, Johnson JA. Health-related quality of life and healthcare utilization in multimorbidity: results of a cross-sectional survey. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(4):791–799. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunes BP, Soares MU, Wachs LS, Volz PM, Saes MO, Duro SMS, Thumé E, Facchini LA. Hospitalization in older adults: association with multimorbidity, primary health care and private health plan. Rev Saude Publica. 2017;51:43. doi: 10.1590/s1518-8787.2017051006646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fialho CB, Lima-Costa MF, Giacomin KC, Loyola Filho AI. Disability and use of health services by the elderly in greater metropolitan Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais state, Brazil: a population-based study. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30(3):599–610. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00090913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mor V, Wilcox V, Rakowski W, Hiris J. Functional transitions among the elderly: patterns, predictors, and related hospital use. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(8):1274–1280. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.8.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs JM, Rottenberg Y, Cohen A, Stessman J. Physical activity and health service utilization among older people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(2):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korda RJ, Joshy G, Paige E, Butler JR, Jorm LR, Liu B, Bauman AE, Banks E. The relationship between body mass index and hospitalisation rates, days in hospital and costs: findings from a large prospective linked data study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e118599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abhaya G, Almas R. Measurement scales used in elderly care. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long WB, Sacco WJ, Coombes SS, Copes WS, Bullock A, Melville JK. Determining normative standards for functional independence measure transitions in rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(2):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinkle JL, McClaran J, Davies J, Ng D. Reliability and validity of the adult alpha functional independence measure instrument in England. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42(1):12–18. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3181c1fd99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ottenbacher KJ, Mann WC, Granger CV, Tomita M, Hurren D, Charvat B. Inter-rater agreement and stability of functional assessment in the community-based elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75(12):1297–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan X, Nan D, Liu S. Preliminary Study on Reliability and Efficacy of Functional Independence Measure. Chin J Phys Med. 1998;3:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Q, Dong S, Xing F, et al. Analysis on the influencing factors of daily life activities among elderly people in Tangshan City. Chin J Gerontol. 2009;29(13):1678–1679. [Google Scholar]

- 33.WHO. The World Health Report 2008-Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). New York; 2008.

- 34.Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, Harlan LC, Klabunde CN, Amsellem M, Bierman AS, Hays RD. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(4):41–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen YC, Rubin HR, Freedman L, Mozes B. Use of a clustered model to identify factors affecting hospital length of stay. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(11):1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagelkerke N. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika. 1991;78(3):691–692. doi: 10.1093/biomet/78.3.691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kutner NG, Zhang R, Huang Y, Painter P. Gait speed and mortality, hospitalization, and functional status change among hemodialysis patients: a US renal data system special study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(2):297–304. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Na L, Pan Q, Xie D, Kurichi JE, Streim JE, Bogner HR, Saliba D, Hennessy S. Activity limitation stages are associated with risk of hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries. PM R. 2017;9(5):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen MS. Use of health services, mental illness, and self-rated disability and health in medical inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):668–675. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000024104.87632.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prata MG, Scheicher ME. Correlation between balance and the level of functional independence among elderly people. Sao Paulo Med J. 2012;130(2):97–101. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802012000200005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nascimento Cde M, Ribeiro AQ, Cotta RM, Acurcio Fde A, Peixoto SV, Priore SE, Franceschini Sdo C. Factors associated with functional ability in Brazilian elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(2):e89–e94. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexandre Tda S, Corona LP, Nunes DP, Santos JL, Duarte YA, Lebrão ML. Gender differences in incidence and determinants of disability in activities of daily living among elderly individuals: SABE study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPhail SM. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;9:143–156. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S97248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bähler C, Huber CA, Brüngger B, Reich O. Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: a claims data based observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grabowski DC, Stewart KA, Broderick SM, Coots LA. Predictors of nursing home hospitalization: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(1):3–39. doi: 10.1177/1077558707308754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mallitt K, Kelly P, Plant N, Usherwood T, Gillespie J, Boyages S, Jan S, Leeder S. Demographic and clinical predictors of unplanned hospital utilisation among chronically ill patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:136. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0789-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gagliardino JJ, Atanasov PK, Chan JC, Mbanya JC, Shestakova MV, Leguet- Dinville P, Annemans L. Resource use associated with type 2 diabetes in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, Eurasia and Turkey: results from the international diabetes management practice study (IDMPS) BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000297. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data might not be shared directly, because it’s our team work and informed consent should be attained from team members.