Abstract

Asthma is considered as one of the most common chronic diseases in the world. As a result of serious physical, social, and psychological complications, asthma can reduce health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The present study was designed to assess the HRQoL including physical health, general health perception, emotional health, psychological health, and social functioning of asthmatic patients in Pakistan. A descriptive cross-sectional study design was used. Setting was public and private healthcare facilities. SF-36 was self-administered to a sample of 382 asthmatic patients. After data collection, data were clean coded and entered in SPSS version 21.0. Skewness test was performed and histograms with normal curves were used to check the normal distribution of data. Descriptive statistics comprising of frequency and percentages was calculated. The non-parametric tests including Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Walis (P ≥ 0.05) were performed to find out the difference among different variables. The results of the current study highlighted a significant impact on several domains of HRQoL for asthmatic patients. Lowest scores for HRQoL were observed in the domain of general health (27.74 ± 18.29) followed by domain of mental health (38.26 ± 20.76) whereas highest scores were observed in the domain of social functioning (45.64 ± 25.89). The results of the study concluded that asthmatic patients in Pakistan had poor HRQoL. Well-structured pharmaceutical care delivery in the healthcare facilities can contribute toward better patient knowledge and management and can ultimately improve the HRQoL of asthma patients.

KEYWORDS: Asthma, chronic diseases, health-related quality of life, health status, Pakistan, SF-36

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases contribute to increasing the burden of illness in many countries across the world.[1,2,3] Asthma causes the loss of 15 million disability-adjusted life years every year.[4] Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is largely compromised in patients with asthma. These patients experience symptoms such as shortness of breath and wheezing.[5] Poor HRQoL contributes negatively toward their health as well as performance thus leading to reduced productivity and absenteeism. HRQoL among these patients is a neglected area in Pakistan. Therefore, the present study was designed to assess HRQoL of asthmatic patients in Pakistan.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A descriptive cross-sectional study design was used to assess the physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems or role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems, or role emotional and emotional well-being among asthmatic patients in Pakistan. The National Bioethical Committee states that only the institutional head’s approval is required for this type of study (National Bioethical Committee, 2011). Moreover in Pakistan, questionnaire-based studies do not need any endorsement from the Ministry of Health. Despite that, prior information was sent to the Ministry of Health, Government of Pakistan, for the execution of this research. For data collection, approval from MS of the hospitals was taken. Informed and verbal consent for participation was also taken from the respondents. A confidentiality undertaking was signed by the principal investigator. Study site for this research were the outpatients’ departments located in public and private healthcare facilities treating asthma in the twin cities of Pakistan. The sampling frame comprised of asthmatic patients treated in public and private healthcare facilities in two cities of Pakistan. Patients suffering from asthma, aged 18 years or older, smokers and nonsmokers, and patients with any disease such as hypertension, diabetes, or any other disease that has no remarkable effect on the asthmatic condition were included in the study. Patients who were younger than 18 years and with any comorbidity that interferes or worsens the condition of asthmatic patients such as pneumonia and lung cancer were excluded from this study.

Sample size and sampling procedure

Sample size was calculated using Rao soft sample size calculator to determine the size of sample representing the population of asthmatic patients. It was calculated as 382 to achieve 95% confidence interval with 5% margin of error. As no list of asthmatic patients was available, convenience sampling technique was used to select the respondents. According to convenience sampling, all the respondents that were available at time of data collection were selected.

Data collection tool

Data collection tool used in this study was the short form health survey (SF-36). Written permission had been obtained from Optum for using SF-36. The tool was slightly modified according to study objectives and sociodemographics of our country. Respondents were greeted and evaluated. If the respondent did not read English or was bilingual, approved language version to use was determined or interviewer administration was used. If visual problems existed, a large-font form was administered or interviewer administration was used. The survey was introduced. Survey form was given to the respondent with instructions on how to fill out the form. Any respondent questions were answered before, during, or after the administration. Form was retrieved upon completion and checked for completeness before the respondent left. Finally, the respondent was thanked for completing the form.

Scoring of the tool

Item response data were entered. Scoring of the SF-36v2 was begun with ensuring that the survey form was complete and the respondent’s answers were unambiguous. Then item response values were recoded. Several steps were included in this process, including changing out-of-range values to missing, recoding values for 10 items, and substituting person-specific estimates for missing items. After item recoding, a total raw score was then computed for each health domain scale. The total raw score is the simple algebraic sum of the final response values for all the items in a given scale. Health domain scale total raw scores were transformed to 0–100 scores using the following formula: ((actual raw score − lowest possible raw score) / possible raw score range) × 100. Health domain scale 0–100 scores were transformed to T scores using health domain z scores.

Reliability and validity of tool

SF-36 is a prevalidated tool but still two focus group discussions had been conducted at different time intervals with experts from hospitals, academia, regulatory, and pharmaceutical industries for face and content validation of the tool. Moreover, pilot testing was conducted at 10% of the sample size to test the reliability of the tool after data collection. The value of Cronbach’s alpha was 0.967 for SF-36, which was satisfactory considering that 0.68 is the cutoff value being disapproved.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected by the principal investigator. The respondents were identified and after obtaining written/verbal consent from them, the questionnaire was hand delivered to them. The questionnaire was collected back on the same day to avoid study bias. After data collection, data were clean coded and entered in SPSS version 21.0. Skewness test was performed, and histograms with normal curves were used to check the normal distribution of data. Descriptive statistics comprising of frequency and percentages was calculated. The nonparametric tests including Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Walis (P ≥ 0.05) were performed to find out the difference among different variables.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

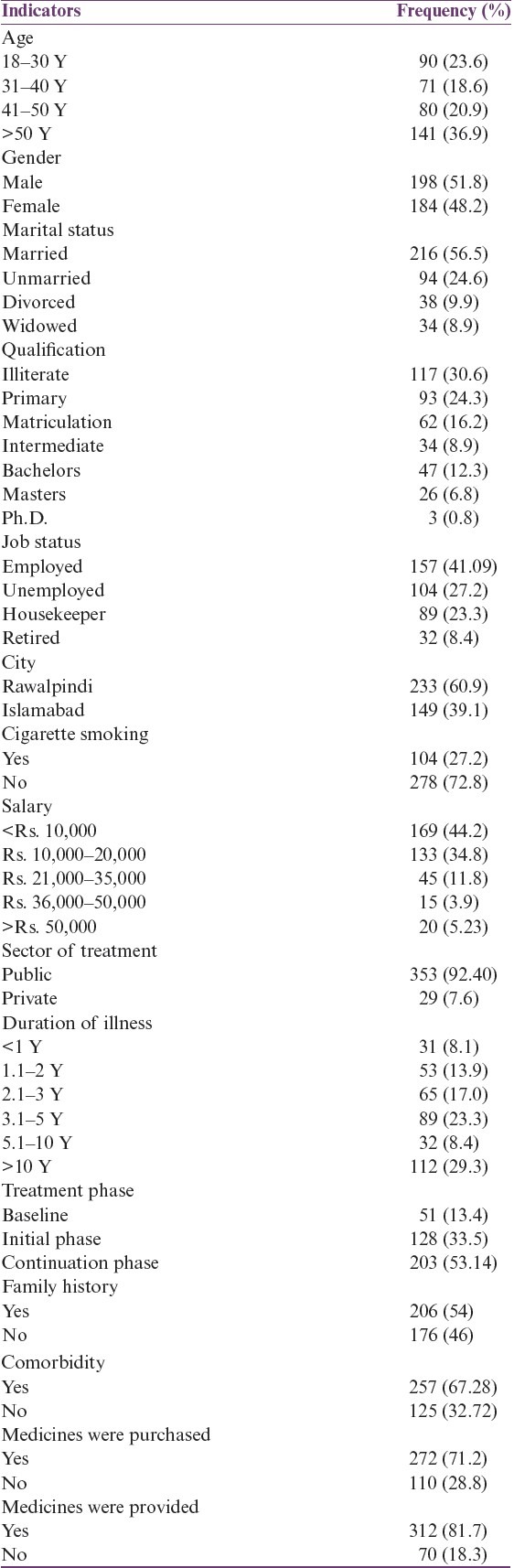

Of 382 respondents, 51.8% (n = 198) were male and 48.2% (n = 184) were female. Seven percent of the respondents were undergoing treatment from private sector healthcare facilities whereas 92.4% (n = 353) from public sector healthcare facilities. Of the total respondents, 8.1% (n = 31) had illness for a duration of <1Y, 13.9% (n = 53) for 1.1–2Y, 17.0% (n = 65) for 2.1–3Y, 23.3% (n = 89) for 3.1–5Y, 8.4% (n = 32) for 5.1–10Y and 29.3% (n = 112) for <10Y. Regarding their treatment phase, 13.4% (n = 51) were undergoing baseline treatment, 33.5% (n = 128) were undergoing initial treatment, and 53.14% (n = 203) were undergoing continuation phase. A detailed description is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

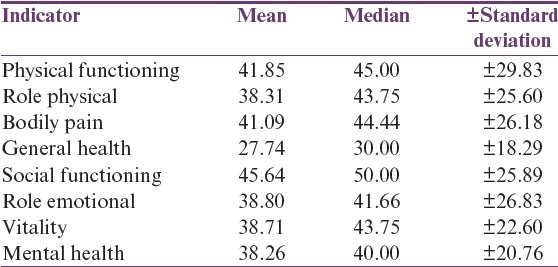

Domains of HRQoL

The results highlighted that lowest scores for HRQoL were observed in the domain of general health (27.74 ± 18.29) followed by domain of mental health (38.26 ± 20.76) whereas highest scores were observed in the domain of social functioning (45.64 ± 25.89). A detailed description is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Domains of HRQoL

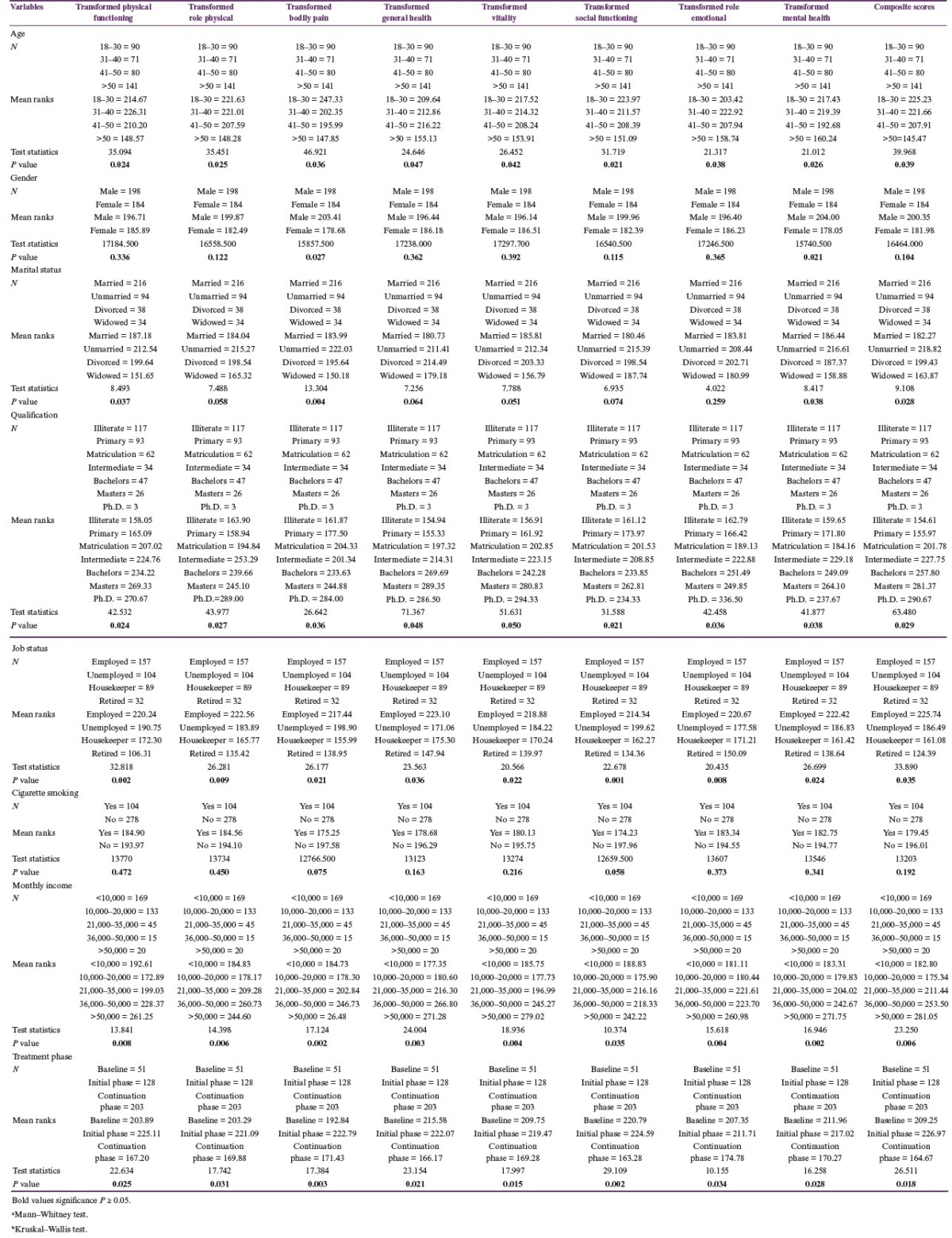

Comparison of HRQoL domains by demographic characteristics

A significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) in bodily pain and mental health scores was observed among different genders of asthmatic patients. Male patients had comparatively better scores than female patients. Significant difference among physical functioning, bodily pain, and mental health scores were observed among asthmatic patients having different marital status. Unmarried patients possessed better HRQoL in all the mentioned domains as compared to married patients. Significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) was observed in HRQoL of asthmatic patients in terms of age, gender, marital status, income, qualification, and job satisfaction. Patients in initial treatment phase had better HRQoL. Patients who were employed and had salary of more than 50,000 rupees had relatively better HRQoL. A detailed description is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of HRQoL domains by demographic characteristics

DISCUSSION

The HRQoL concept has evolved significantly during the past few years as the quality of life was seen being altered in patients of chronic diseases. The results of the present study reported poor HRQoL among asthmatic patients in the twin cities of Pakistan. Inadequate number of hospital pharmacists, their accepted role, and lack of pharmaceutical care model are the major factors contributing to poor HRQoL among the chronic disease patients in Pakistan. Similar findings from another study conducted in the UK reported impaired HRQoL in patients with asthma.[6] Moreover, the current study revealed that asthmatic patients older than 50 years of age had poor quality of life in all domains whereas patients belonging to age group of 18–30 years had overall best HRQoL in all domains. This might be due to the fact that in old age physiological changes in lung function can lead to deterioration of health status of an asthmatic patient as compared to a young adult. Decreased cognitive impairment and presence of comorbidities can lead to nonadherence to treatment further reducing the HRQoL. Similar findings were reported from studies conducted in India and Spain highlighting the deterioration of HRQoL with the intensity and severity of disease with progressing age.[7,8]

The findings of the current study showed that female patients with asthma were more likely to suffer from poor HRQoL as compared to the opposite gender. The best heath domain in majority of the male as well as female respondents was social functioning. This might be due to severe dyspnea and a higher level of medication use among women. Similar findings were reported from other studies conducted in India and Netherlands which highlighted that patients’ age and gender have an impact on the HRQoL.[9,10] Furthermore, the results of the present study revealed that among patients with asthma those with higher qualification had better HRQoL. This might be due to inadequate knowledge of disease due to low literacy level. The results of the present study are in line with the study conducted in Canada where patients with lower educational level had lower health literacy as well as poor mathematical skills, poor access to health care, more delayed diagnosis of asthma, or less adherence to healthy lifestyles, which contributed toward worsening of HRQoL in these patients.[11]

The current study showed better HRQoL among employed patients. The results of the present study are in line with another study that reported better HRQoL in patients who remain in active employment.[12] Cigarette smoking seems to worsen respiratory diseases. The results of the present study highlighted poor HRQoL among patients with asthma who were also smokers. Similar results were reported by a study conducted in Atlanta.[13] The results of the present study highlighted that patients who had monthly income greater than 50,000 rupees possessed better HRQoL. Similar results were reported from various studies where poor socioeconomic status was shown to be a contributing factor for poor HRQoL among patients with asthma.[14,15,16]

CONCLUSION

The results of the present study concluded that patients with asthma in Pakistan had poor HRQoL. General health was the most affected domain in terms of HRQoL whereas social functioning was the best domain. Poor HRQoL was observed in females, the elderly, widowed, illiterate, smokers, retired people, and patients with poor socioeconomic status and in continuous phase of treatment. Innovative strategies must be designed by involving all the relevant stakeholders for effective control of asthma. Well-structured pharmaceutical care delivery in the healthcare facilities can contribute toward better patient knowledge and management and can ultimately improve the HRQoL of patients with asthma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge all the public and private healthcare facilities for sharing their data and facilitating the data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Australian Centre for Asthma Monitoring. Measuring the impact of asthma on quality of life in the Australian population. AIHW Cat No. ACM 3. Canberra: AIHW; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Gewely MS, El-Hosseiny M, Abou Elezz NF, El-Ghoneimy DH, Hassan AM. Health-related quality of life in childhood bronchial asthma. Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;11:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leander M. Health-related quality of life in asthma. J Asthma. 2010;47:1–6. doi: 10.3109/02770901003617402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander Oni O, McNeal PL, Erhabor GE, Oluboyo PO. Does health-related quality of life in asthma patients correlate with the clinical indices? S Afr Fam Pract. 2014;56:134–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adeniyi BO, Moore VC, Erhabor GE, Burge S. Differences in serial lung function recorded on four data-logging meters. J Asthma. 2013;50:965–7. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.825726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tejirian T, Heaney A, Colquhoun S, Nissen N. Laparoscopic debridement of hepatic necrosis after hepatic artery chemoembolization. JSLS. 2007;11:493–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malpani AK, Waggi M, Santhekudlur Mukunda M, Jampa K, Sindhuri M. A study on assessment of health related quality of life in COPD and asthma patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital. IJOPP. 2015;8:35. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wijnhoven HAH, Kriegsman DMW, Snoek FJ, Hesselink AE, de Haan M. Gender differences in health-related quality of life among asthma patients. J Asthma. 2003;40:189–99. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh HR, De AS, Baveja SM. Comparison of the lysis centrifugation method with the conventional blood culture method in cases of sepsis in a tertiary care hospital. J Lab Physicians. 2012;4:89–93. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.105588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naveed S, Quari H, Panjawani G, Shah A, Panday BB. Evaluation of clinicopathological findings on 255 cases of inoperable locally advanced breast carcinoma: A tertiary care experience. Gulf J Oncol. 2016;1:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos MS, Jung H, Peyrovi J, Lou W, Liss GM, Tarlo SM. Occupational asthma and work-exacerbated asthma: Factors associated with time to diagnostic steps. Chest. 2007;131:1768–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siroux V, Boudier A, Bousquet J, Vignoud L, Gormand F, Just J et al. Asthma control assessed in the EGEA epidemiological survey and health-related quality of life. Respir Med. 2012;106:820–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strine TW, Ford ES, Balluz L, Chapman DP, Mokdad AH. Risk behaviors and health-related quality of life among adults with asthma: The role of mental health status. Chest. 2004;126:849–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amin A. Commentary on “new techniques and developments of stenting for infrainguinal arterial occlusive disease: Are the results any better than balloon angioplasty alone?”. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2007;19:307–8. doi: 10.1177/1531003507307073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husain N, Chaudhry IB, Afridi MA, Tomenson B, Creed F. Life stress and depression in a tribal area of Pakistan. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:36–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumford DB, Saeed K, Ahmad I, Latif S, Mubbashar MH. Stress and psychiatric disorder in rural punjab.A community survey. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:473–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.5.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]