Abstract

Background

Changes in migration patterns that have occurred in recent decades, both quantitative, with an increase in the number of immigrants, and qualitative, due to different causes of migration (work, family reunification, asylum seekers and refugees) require constant u pdating of the analysis of how immigrants access health services. Understanding of the existence of changes in use patterns is necessary to adapt health services to the new socio-demographic reality. The aim of this study is to describe the scientific evidence that assess the differences in the use of health services between immigrant and native populations.

Methods

A systematic review of the electronic database MEDLINE (PubMed) was conducted with a search of studies published between June 2013 and February 2016 that addressed the use of health services and compared immigrants with native populations. MeSH terms and key words comprised Health Services Needs and Demands/Accessibility/Disparities/Emigrants and Immigrants/Native/Ethnic Groups. The electronic search was supplemented by a manual search of grey literature. The following information was extracted from each publication: context of the study (place and year), characteristics of the included population (definition of immigrants and their sub-groups), methodological domains (design of the study, source of information, statistical analysis, variables of health care use assessed, measures of need, socio-economic indicators) and main results.

Results

Thirty-six publications were included, 28 from Europe and 8 from other countries. Twenty-four papers analysed the use of primary care, 17 the use of specialist services (including hospitalizations or emergency care), 18 considered several levels of care and 11 assessed mental health services. The characteristics of immigrants included country of origin, legal status, reasons for migration, length of stay, different generations and socio-demographic variables and need. In general, use of health services by the immigrants was less than or equal to the native population, although some differences between immigrants were also identified.

Conclusions

This review has identified that immigrants show a general tendency towards a lower use of health services than native populations and that there are significant differences within immigrant sub-groups in terms of their patterns of utilization. Further studies should include information categorizing and evaluating the diversity within the immigrant population.

Keywords: Access to health care, Immigrants and native born

Background

The number of international migrants continues to grow each year. According to the United Nations Migration Report, the number of migrants has reached 244 million in 2015 up from 191 million in 2005, representing an increase of 28% over the decade in comparison with an increase of 13% during the period 1990–2000 [1, 2].

Between 2000 and 2015, Europe has absorbed the second largest number of international migrants following Asia [1, 3]. Despite the global economic crisis which started in 2007–2008, Europe and Northern America have recorded an annual growth rate in the international migrant stock of 2% per year [1].

These transformations have both quantitative (i.e. an increasing number of migrants) and qualitative (i.e. evolving reasons for migration) aspects. There is a trend towards permanent migration and reunification of families with immigrant setting in the host country in a more definitive way [4]. And most recently, we have seen an increasing number of asylum seekers and refugees, which is reaching the highest levels seen since World War II [1].

This situation has generated various responses in the host countries, as immigration is acquiring a significant social and political dimension. Immigration is influencing public opinion and triggering a debate, often improperly informed, regarding the pressure on public services—including health services [3]. This has even led to the adoption of new legislation [5–7] limiting access to health care for migrants, that may pose, as a result, a risk to public health.

The dramatic changes in demographics, socio-economics and politics require an update of the analysis of health service utilization by immigrants in order to properly determine the breadth and scope of the current situation. Consequently, research on migrant access and utilization of health services has proliferated in recent decades [8, 9]. Results from a previous review point to a lower utilization rate of general and specialist medical services by immigrants compared to native-born populations [10]. However, and since patterns of healthcare utilization depend on factors that may have evolved in recent years, such as age, sex, socio-economic level, time of stay in the host country or origin of the immigrants, and the specific features of healthcare services of the host countries, it seems necessary to revisit the state of knowledge on this subject.

The objective of this study is to describe the available scientific evidence that has investigated the differences in healthcare service utilization between immigrant and native populations in the last 3 years (June 2013 through February 2016), and to explore the possible effect on the differential use of variables associated with health needs, socio-economic status or other factors.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed to identity the available empirical evidence comparing immigrant’s healthcare utilization with native populations using a predefined protocol [10]. Inclusion criteria for articles to be considered were original studies with quantitative data that compared the use of healthcare services between native and immigrant populations. Service use was defined as the interaction between health professionals and patients [11]. Only studies with both population groups properly defined, i.e. immigrant and native, were included. For the purposes of this review, we used the European Union definition of immigrant status based on foreign country of birth including up to the second generation [12].

Papers that considered undocumented immigrants, asylum seekers and/or refugees were also included. The indigenous majority population served as the native reference group. No limitation in gender or ethnic characteristics was stipulated.

Articles were excluded if they (1) exclusively evaluated healthcare utilization for children or adolescents younger than 18 years of age, (2) were editorials, letters or reviews and (3) were qualitative studies.

Search strategy and study selection

Two strategies were utilized in the search for relevant articles on this review.

Firstly, in February 2016, a librarian conducted a systematic review of the electronic database MEDLINE (PubMed) in search of the literature published between June 2013 and February 2016. No language restrictions were applied; no authors were contacted for additional information. MeSH terms and key words used, as well as search strategies performed, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy for healthcare service utilization’s comparative studies

| General practitioner use (electronic search): | ||

| 1. Health Services Needs and Demand/ | 12. health services [Title] | 23. 18–22 / OR |

| 2. Health Status/ | 13. Primary care [Title] | 24. immigrant* [Title] |

| 3. Health Services Accessibility/ | 14. Emergency services [Title] | 25. migrant* [Title] |

| 4. Coverage [Title] | 15. Utilization patterns [Title] | 26. Ethnic Groups [Title] |

| 5. 1–4 / OR | 16. 6–15/ OR | 27. 24–26 / OR |

| 6. health care [Title] | 17. 5 and 16 | 28. 23 and 27 |

| 7. health disparities [Title] | 18. Emigration and Immigration/ | 29. Health AND utilization AND immigrant* [Title] |

| 8. access to care [Title] | 19. Emigrants and Immigrants/ | 30. 17 AND 28 |

| 9. health resources [Title] | 20. Native [Title] | 31. 29 or 30 (GPs precise search) |

| 10. health profiles [Title] | 21. Foreign [Title] | 32. (16 AND 27) OR 29 (GPs exhaustive search) |

| 11. health status [Title] | 22. Autochthonous [Title] | |

| Specialist use (electronic search): | ||

| 1. Health Services/utilization/ | 7. Emigrants and Immigrants/ | 13. Specialization/ |

| 2. Health Services Accessibility/ | 8. Ethnic Groups | 14. speciali* [TI] |

| 3. Health Status/ | 9. Native [Title] | 15. 13 OR 14 |

| 4. Coverage [Title] | 10. Foreign [Title] | 16. 5 AND 12 AND 15 |

| 5. 1–4 / OR | 11. Autochthonous [Title] | |

| 6. Emigration and Immigration/ | 12. 6–11 / OR | |

The initial screening of the articles was based on abstracts. Two researchers reviewed all abstracts independently. Selection of relevant articles was based on the information obtained from the abstracts and was agreed upon in discussion. If the abstract was not available, the full text was examined. In the case of discrepancies between the two researchers, the original paper was obtained and an agreement was achieved after it was read.

Secondly, a researcher (AIHG) conducted a manual search of grey literature through Google Scholar, including published papers from 2013 through February 2016 taking into account the terms (Health care use; Comparison; Immigrants; Natives) and (Needs, demands and barriers; Coverage; Primary care; Emergency services; Utilization patterns; Native; Foreign; Autochthonous; Immigrant). Both English and Spanish web pages were included in the search results. Appropriateness for inclusion was based on titles; in the event of doubt, abstracts were retrieved. Studies without electronic abstracts were not included.

Subsequently, two researchers examined the full text of all papers that satisfied the inclusion criteria (AIHG, ASS).

Data extraction

The following information were extracted from each publication: context of the study (country and year), characteristics of the included population (definition of native and immigrants groups, sample size for each group), methodological components (design of the study, statistical analysis, source of information), area of healthcare services assessed, confounders affecting healthcare utilization (individual determinants, measures of need, socio-economic indicators, cultural factors), objective of the study and main results.

Results

Characteristics of the studies

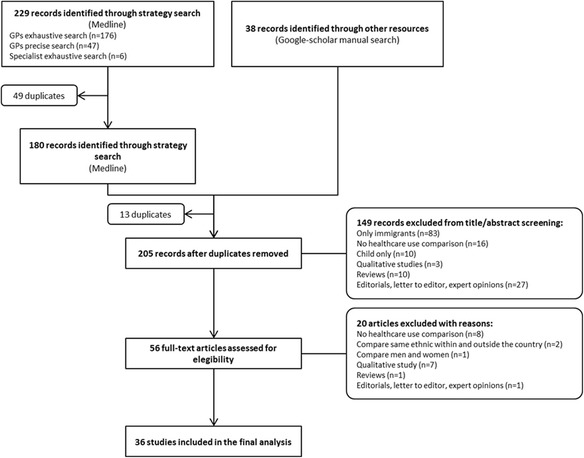

Thirty-six papers met the inclusion criteria in this study. The process followed to include those papers is shown in Fig. 1. Table 2 shows the information extracted from the included publications. Of the 36 studies included, 8 were duplicated in both the manual and electronic search [13–20], 12 were included after the manual search [21–32] and 16 through the electronic search [33–48]. Among them, at least 9 partly describe the same dataset [13–16, 19, 20, 25, 47, 48]. Nevertheless, as these articles focused on different aspects of healthcare use or outcome measures, all were included in this review.

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart for the selection process of the final included studies

Table 2.

Descriptive summary of the studies included in the review

| Reference | Country | Year | Sample | Objectives | Information sources | Dependent variable | Independent variable (migrant definition) | Need indicators | Socio-economic indicators | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeida LM et al. [33] 2014 |

Portugal | 2012 | 277 women Migrants (n = 89) Portuguese (n = 188) | To evaluate differences in obstetric care between immigrant and native women in a country with free access to health care | Register and survey-based study (1) Administrative databases of the four public maternity hospitals (February 1 and December 31, 2012) (2) Telephone survey |

(1) First appointment at >12 weeks (2) Number of prenatal visits | (1) Native: born in Portugal (2) Immigrant: born outside Portugal with both parents born outside Portugal | Age Parity | Family income Education level Marital status | Migrants were more prone to late prenatal care (first pregnancy appointment after 12 weeks of pregnancy, to have fewer than three prenatal visits) |

| Beiser M et al. [21] 2014 |

Canada | 2009–2010 | 98,346 individuals Native born (n = 83,949) Established migrants (n = 10,810) Recent immigrants (n = 3587) 20–74 years | To examine the effects of chronic health conditions, as well as personal resources and regional context on labour force participation, receipt of government transfer payments and use of health services by short- and long-stay immigrants compared with native-born Canadians | Survey-based study Canada Community Health Survey (CCHS) |

(1) GP visits in the past 12 months (2) Labour force participation (3) Use of government transfer payments | (1) Native-born Canadians (2) Recent immigrants (resident in Canada for 10 years or less) (3) Established immigrants (present in Canada for more than 10 years) | Age & gender Chronic physical conditions (last 6 months or more) Chronic mental conditions | Education level Marital status Official-language ability (English or French) Geographic region | Recent immigrants healthy or with chronic health problems made fewer GP visits Established immigrants with chronic conditions did not differ in their use of GP |

| Berchet C [22] 2013 |

France | 2006–08 | 12,999 individuals French (n = 11,934) Immigrants (n = 1065) ≥18 years | To highlight factors generating healthcare use inequalities relating to immigration | Survey-based study Health Survey (l’Enquête sur la santé et la protection sociale-ESPS) |

(1) GP visits (last year) (2) Specialist medical visits (last year) | Nationality and country of birth (subject and parents) | Age & gender Self-rated health Chronic disease and functional limitations Health behaviour (smoke, overweight) | Health insurance Education level Employment status Family composition Isolation and social support Place of residence GP’s and specialist’s patient load | Immigrants present a lower demand for GP and specialist care |

| Carmona-Alférez MR [23] 2013 |

Spain (Madrid) | 2006–2007 | 835,401 individuals Natives (n = 694,716) Immigrants (n = 140,685) 25–64 years | To evaluate the relationship between birthplace of users of PHC in the Community of Madrid (CM) and the referrals to specialists | Register-based study Medical records of PHC (OMI-AP) |

(1) Referral to specialists (2) Number of referrals | Country of birth | Age & gender Health problems (last 12 months) Number of visits to the GP (last 12 months) Territorial per capital income GP’s patient load | – | Immigrants from South America had higher probability to be referred for any health problem, while Asiatic immigrants have the lowest overall probability of referrals Immigrants from Western countries, Central America and the Caribbean showed similar referral rates to Spanish natives |

| De Back TR et al. [34] 2015 |

Netherlands | 2009–2010 | 60,852 patients with hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular accidents and cardiac failure Native Dutch (n = 55,320) Immigrant Moluccan immigrant (n = 5532) | To determine the frequency of visits to the medical specialist and GP and the prescription of cardiovascular agents among Moluccans compared to native Dutch | Register-based study Registry data from the Achmea Health Insurance Company (Achmea) |

(1) Number of GP visits (2) Number of specialist (cardiologist and neurologist) visits | Moluccan and Dutch surnames | Age & gender | Socio-economic status (SES) Area-level SES scores were composed by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research Place of residence | Cardiovascular healthcare use of ethnic minority groups may converge towards that of the majority population |

| De Luca G et al. [24] 2013 |

Italy | 2004–2005 | 102,857 individuals Natives (n = 97,229) Immigrants (n = 5628) 0–64 years | To explore differences in utilization of health services between the immigrant and the native-born populations | Survey-based study Italian Health Conditions survey (ISTAT-Condizioni di salute e Ricorso ai Servizi Sanitari) |

(1) GP visits (last 4 weeks) (2) Specialist medical visits (last 4 weeks) (3) Phone consultations (last 4 weeks) (4) ED care visits (last 4 weeks) | Country of birth and citizenship criteria (1) Native (Italian citizens born in Italy) (2) First-generation immigrants (individuals born outside of Italy without Italian citizenship) (3) Second-generation immigrants (individuals born in Italy without Italian citizenship) (4) Naturalized Italians (individuals born outside of Italy with Italian citizenship) | Age & gender Self-assessed family wealth Self-assessed health status Chronic diseases and disability conditions Health behaviour (smoke, weight-checking, physical activity) | Education level Marital status Employment status Number of children in the household Area of residence | Immigrants tend to use specialist services and have telephone consultations less frequently, whereas they use ED services more often |

| Díaz E et al. [13] 2015 |

Norway | 2008 | 25,915 patients diagnosed with dementia or memory impairment in PHC Natives (n = 25,117) Immigrants (n = 788) ≥50 years | To study utilization of primary healthcare services of Norwegians and immigrants with either a diagnosis of dementia or memory impairment | Register-based study (1) National Population Register-NPR (2) Norwegian Health Economics Administration database-HELFO (3) Norwegian Prescription Database-NorPD |

(1) Number of GP visits (2) ED visits (3) Home consultations | Country of birth. (Born abroad with both parents from abroad) | Age & gender | Education level Marital status Length of stay in Norway Place of residence |

No differences in the use of PHC were found |

| Díaz E et al. [14] 2014 |

Norway | 2008 | 3,739,244 individuals Natives (n = 3,349,721) Immigrants (n = 389,523) ≥15 years | To describe and compare the use and frequency of use of PHC services between immigrants and natives in Norway To investigate the importance of morbidity burden, socio-economic status and length of stay in Norway for immigrants’ use of PHC services | Register-based study (1) National Population Register (2) Norwegian Health Economics Administration database-HELFO |

(1) Percentage of each population who had used the PHC system (GPs, EPC and both) in 2008 (2) Frequency of use among PHC users | Country of birth (1) Natives (born in Norway with both parents born in Norway) (2) Immigrants (born abroad with both parents from abroad) staying at least 6 months, divided according to the World Bank income categories of their country of origin | Age & gender Morbidity groups (Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups) | Education level Marital status Income level Place of residence | Significantly fewer immigrants from all but LIC used their GP and all PHC services, but a higher share of immigrants except those from HIC used the EPC. This higher use did not compensate for less use of GPs in terms of overall use of PHC Among GP users, however, immigrants used the GP at a statistically significant higher rate compared with natives Immigrants 65 years from all but HIC used GPs less than other age groups, and the same was true for overall use of PHC, although older immigrants from LIC used the EPC most The use of PHC services, but not the rate of use, increased with length of stay in Norway |

| Díaz E et al. [15] 2014 |

Norway | 2008 | 1,605,873 individuals Natives (n = 1,516,012) Immigrants (n = 89,861) ≥50 years | To describe the utilization of PHC in Norway in terms of number of consultations, diagnoses given and procedures undertaken To compare native Norwegians’ use of PHC services with that of different immigrant groups | Register-based study (1) National Population Register (2) Norwegian Health Economics Administration database-HELFO |

(1) Frequency of use of PHC system (GP, EPC) in 2008 (2) Diagnoses received at GP and EPC consultations | Country of birth (1) Natives (born in Norway with both parents born in Norway) (2) Immigrants (born abroad with both parents from abroad) staying at least 6 months, divided according to the World Bank income categories of their country of origin | Age & gender Morbidity groups (Johns Hopkins University Adjusted Clinical Groups) | Education level Marital status Income level Length of stay in Norway Place of residence Reason for migration Age at migration | A lower proportion of HIC immigrants used PHC, but utilization was increasingly similar in older age groups The mean number of consultations to both the GP and the EPC, and the mean number of different diagnoses for PHC users were higher for 50 to 65 years old OIC immigrants, but this pattern was reversed for older adults |

| Durbin A et al. [25] 2015 |

Canada (Ontario) | 1993–2012 | 1,820,443 individuals Long-term residents (n = 908,329) Immigrants (n = 912,114) 18–105 years | Examine the use of primary care and specialty services for non-psychotic mental health disorders by immigrants to Ontario Canada during their first 5 years after arrival | Register-based study (1) OHIP claims data (2) Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database (3) Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (4) National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (April 1, 1993–March 31, 2012) |

1) Visits to PHC physicians 2) Visits to psychiatrists 3) Composite of ED visits or hospital admissions | Country of birth (1) Long-term residents (newcomer before 1985 and Canadian-born) (2) Immigrants (identified through the Ontario Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) database) | Age & gender | Education level Marital status Income level Length of stay Official language speaking ability Immigrant admission category Neighbourhood | Immigrants were more or less likely to access primary mental health care depending on the world region of origin Regarding specialty mental health care (psychiatry and hospital care), immigrants used it less. Across the 3 mental health services, estimates of use by immigrant region groups were among the lowest for newcomers from East Asian and Pacific and among the highest for persons from Middle East and North Africa |

| Durbin A et al. [16] 2014 |

Canada (Ontario) | 2002–2012 | 359,673 individuals LT-Residents (n = 163,263) Immigrants (n = 163,298) 18–105 years | To compare service use (primary care visits, visits for psychiatric care, and hospital use) for non-psychotic mental disorders by recent immigrants by matched long-term residents | Register-based study (1) OHIP claims data (2) Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database (3) Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (4) National Ambulatory Care Reporting System | (1) Visits to PHC physicians (2) Visits to psychiatrists (3) Composite of ED visits or hospital admissions | Country of birth (1) Long-term residents (newcomer before 1985 and Canadian-born) (2) Immigrants (identified through the Ontario Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) database) | Age & gender | Education level Income level Official language speaking ability Immigrant admission category Neighbourhood | Immigrants in all admission classes and of both sexes were generally less likely to use all three types of mental health service. The exceptions were for primary mental health care, where male refugees were more likely to have at least one visit For PHC, estimates of intensity of use were highest for refugees and lowest for economic class immigrants For psychiatric care and hospital care, estimates were similar across admission class groups |

| Esscher A et al. [35] 2014 |

Sweden | 1988–2010 | 74 individuals Natives (n = 48) Immigrants (n = 26) | To identify suboptimal factors of maternity care related to maternal death as it occurred in Sweden over a period of increased migration of childbearing women from LIC and MIC | Register-based study (1) Swedish official and national registries (1988–2007) (2) Swedish Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (SFOG) Maternal Mortality Group (2008–2010) | Factors of suboptimal care (1) Delay of care-seeking (non-compliance, late booking) (2) Accessibility of services (language proficiency, legal status, transport) (3) Quality of care (Insufficient surveillance and delayed treatment, miscommunication between providers, limited use of resources) | Country of birth divided according to the World Bank Income categories (1) LIC (Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Gambia, and Pakistan) (2) MIC (Poland, Former Yugoslavia, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Morocco, Philippines, and Thailand) | Age Causes of death | – | Suboptimal care was a significantly more frequent contributing factor of maternal death for the foreign-born women. Many of these deaths were associated with communication-related barriers and delays in care-seeking Immigrant lower health coverage represents the first factor generating inequalities in the propensity to contact a GP, while education and income are the most important drivers of inequalities in the propensity to contact a specialist |

| Fosse-Edorh S et al. [36] 2014 |

France | 2002–2007 | 13,959 individuals Born in France (n = 12,711) Born in North Africa (n = 327) ≥45 years | The objective of the present study was to determine DT2 prevalence and management in immigrants from North Africa living in France to ascertain whether the higher diabetes mortality observed in this population compared with the French-born population reflected a higher prevalence of DT2, poorer health status and or lower quality of care | Survey-based study (1) Population-based survey Enquête décennale santé (EDS; Decennial Health Survey) 2002–2003 (2) ENTRED (Échantillon national témoin représentati des personnes diabétiques; National representative sample of people with diabetes) survey 2007 | (1)GP visits last year (2) ≥ 1 private specialist (ophthalmologist or endocrinologist) visit last year (3) Hospitalization >24 h last year 4) Length of stay of hospitalization | Country of birth (1) Born in France (2) Born in North Africa |

Age & gender Diabetes complications Smoking | Education level Financial difficulty | Reflects a greater prevalence of DT2, poorer health status and/or lower quality of care in this population Our present study found no major differences between patient groups in terms of medical visits except for less frequent GP and more frequent dentist visits in the BNA population |

| Franchi C et al. [37] 2016 |

Italy (Lombardy region) | 2010 | 51,016 individuals Natives (n = 25,508) Immigrants (n = 25,508) 65–94 years | To compare healthcare resource utilization (drug prescriptions, hospital admissions and healthcare services) in regular immigrants living in the Lombardy Region of Northern Italy at least 10 years versus native elderly people (65 years or older) | Register-based study Administrative databases of Lombardy region (1) Anagraphic database (2) Prescription database (3) Hospital discharge database (4) Outpatient prescriptions by GP (healthcare services utilization) |

Drug prescription Polytherapy Hospital admissions Healthcare service utilization | (1) Regular immigrant (born in a country other than Italy and registered with the Italian NHS) (2) Native (born in Lombardy) | Age & gender | – | Older immigrants (65 years and older) present under-utilization of healthcare resources and prescriptions drugs, including those from HIC European countries Only immigrants from Eastern Europe and Eastern Africa have a higher prevalence for hospital admissions. Only immigrants from Northern Africa have higher rate of prescriptions |

| Garcia-Subirats I et al. [38] 2014 |

Spain | 2006–2007 & 2011–2012 | 2006–2007 21,818 individuals Natives (n = 18,504) Immigrants (n = 2893) 2011–2012 15,200 individuals (n = 12,559) Immigrants (n = 2390) 16–59 years |

To analyse the changes in access to health care and the determinants of access among the immigrant and autochthonous populations in Spain between 2006 and 2012 | Survey-based study Spanish National Health Survey (SNHS) of 2006–2007 and the SNHS of 2011–2012 |

(1) Unmet healthcare need in the last 12 months (2) Visits to a GP in the last 4 weeks (3) Visit to a specialist in the last 4 weeks (4) Hospitalization in the last year (5) ED visits in the last year | Country of birth (low and middle-income countries according to the World Bank Income classification) | Age & gender Self-rated health, suffering from a chronic disease, having suffered an injury in the past year | Private health insurance policy Education level Marital status Employment situation Social class (following classification of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology) Length of stay (Immigrants in the SNHS 2011–2012) | In 2012 the immigrant population had a higher prevalence of visiting the GP compared to 2006 The immigrant population had a lower prevalence of visiting the specialist both in 2006 and 2012 The difference in use of ED decreased slightly for both groups and the difference between them was maintained from 2006 to 2012; the immigrant population showed a higher prevalence of use of this care level No significant differences were found between both populations in terms of hospitalizations |

| Gazard B et al. [26] 2015 |

United Kingdom, UK (Southeast London, Lambeth and Southwark) | 2008–2010 | 1698 individuals Non-immigrant (n = 1010) Immigrants (n = 659) ≥16 years | (1) To describe the socio-demographic and socio-economic differences between migrants and non-migrants as broad groupings and by ethnicity, as well as within migrant groups by length of residence in the UK (2) To investigate the associations between migration status and health-related outcomes, including health behaviours, functional limitations, physical and mental health status and health service use (3) To examine whether and how the effect of migration status changes when it is disaggregated by length of residence, first language,reason for migration and combined with ethnicity | Survey-based study South East London Community Health (SELCoH) survey |

(1) Registration with GP (2) Visits to a GP for an emotional problem in the last 12 months (3) Seen a counsellor or mental health specialist in the last 12 months (4) Use of hospital services (accident and emergency and other outpatient department) in the last 12 months | (1) Migration status (2) Length of residence in the UK (3) First language (4) Reason for migration (5) Migration status within each ethnic group category | Age & gender Ethnicity | Educational level Employment status Household income Migrant status Length of residence | Migrants who had been in the UK for < 5 years, white migrants and those who migrated for education or work had increased odds of not being currently registered with a GP Migrants who had been in the UK for 5–10 years had increased odds of seeing a GP for an emotional problem. Those who had resided in the UK for <5 years had decreased odds Those who had migrated for education had increased odds of visiting an outpatient department compared to non-migrants decreased odds of seeing a GP for an emotional problem |

| Gimeno-Feliu LA et al. [27] 2016 |

Spain (Aragón) & Norway | Norway 2008 & Spain 2010 | Native born: Spain (n = 1,102,391) Norway (n = 4,351,084) Immigrants: Spain (n = 35,851) Norway (n = 60,733) |

Analyse all registered pharmacological treatments for immigrants from Poland, China, Morocco and Colombia compared to natives, aiming to identify patterns of drug use for each immigrant group compared to host countries | Register-based study (1) Pharmaceutical Billing Database in Aragon (2) Norwegian Prescription Database-NorPD |

Drug prescription | Country of birth (Poland, Chine, Colombia & Morocco) | Age & gender | – | In the two countries studied, the proportion of immigrants that purchased drugs was significantly lower than that of the correspondingnative population Immigrants from Morocco showed the highest drug purchase rates in relation to natives, especially for antidepressants, pain killers and drugs for peptic ulcer. Immigrants from China and Poland showed lowest purchasing rates, while Colombians where more similar to host countries |

| Gimeno-Feliu LA et al. [39] 2013 |

Spain (Aragón) | 2007 | 594,145 individuals Natives (n = 527,881) Immigrants (n = 66,264) All ages | (1) To analyse the use of primary care services by immigrants compared to Spanish nationals, adjusted by age and sex (2) To analyse the differences in frequency of visits to primary care in relation to geographic origin | Register-based study Electronic medical records register (OMI: Computerized Medical Office) |

(1) GP appointments (2) Paediatric appointments (3) Nurse appointments (4) Midwife appointments (5) Physiotherapy appointments (6) Dental appointments (7) Social worker appointments (8) PHC team appointments | Nationality | Age & gender | – | The immigrant population makes less use of PHC services. This is evident for all age groups and regardless of immigrants’ countries of origin |

| Klaufus L et al. [40] 2014 |

Netherlands | 2008 | 14,131 individuals Native born (n = 11,678) Immigrants (n = 2453) >14 years | To investigate ethnic differences as a factor in mental healthcare consumption in patients with medium & high risk of CMD (common mental disorders) and to identify determinants that may explain possible ethnic differences | Survey-based study Health survey conducted by Public Health Services (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and the Hague) |

(1) GP visits (last year) (2) Mental health visit (psychiatrist, psychologist or a mental health care facility) last year | Country of birth (subject and parents) (1) Native Dutch (2) First-generation immigrant (foreign born and almost one parent foreign born) (2) Second-generation immigrant (born in Netherland with at least one parent foreign born) |

Age & gender Physical health problems | Education level Marital status Employment status Financial situation Social loneliness | Ethnic minority groups contacted the GP significantly more often than native Dutch people, with the exception of Antillean/Aruban immigrants First-generation immigrants tended to contact the GP more often than second-generation immigrants The four ethnic minority groups visited a mental healthcare specialist more often than the Dutch; this was significantly higher among the Turks |

| Kerkenaar M et al. [41] 2013 |

Austria | October 2010–September 2011 | 3448 individuals Natives (n = 2930) Immigrants (n = 518) ≥15 years | To study: (1) the prevalence of dysphoric disorders among different groups of migrants (first and second generation from different regions) in comparison to the native Austrian population using a validated questionnaire (2) The influence of gender, socio-economic factors, fluency of host language and length of stay in Austria on this prevalence (3) The utilization of healthcare services of migrants and Austrians with and without a dysphoric disorder | Survey-based study (Telephone survey ad hoc and PHQ-4) |

(1) Visits to a GP in the last 4 weeks (2) Visits to specialists in their own practices in the last 4 weeks (3) Out or inpatient hospital care in the last 4 weeks (4) Prevalence of dysphoric disorders | Country of birth and country of birth of fathers | Age & gender Chronic disease | Education level Employment status Living area Persons in house | No significant difference was found in the utilization of healthcare services associated with dysphoric disorders, except for a higher utilization of secondary/tertiary care by female migrants with a dysphoric disorder Immigrant males without dysphoric disorders had a lower utilization rate |

| Koopmans GT et al. [17] 2013 |

Netherlands | 2001–2003 | 9077 individuals Native Dutch (n = 7772) Immigrants (n = 1305) ≥18 years | To investigate ethnic-related differences in utilization in outpatient mental health care | Survey-based study Dutch Second National Survey of General Practice (A representative sample of 104 GP practices) |

Contact with any mental health service during the last 12 months | Place of birth (subject and parents) Surinamese, Dutch, Antilleans, Moroccans and Turks | Age & gender Self-reported mental health | Education level Marital status Proficiency in Dutch language Orientation towards modern western values Lay views on illness and treatment | Migrant group’s utilization is about half the level of the native Dutch |

| Lee CH et al. [42] 2013 |

Singapore | 2008–2010 | 374 patients with diagnosis of STEMI Singapore-born citizens (n = 286) Immigrants (n = 88) | To study disparities in accessibility to high quality health care, and if patients’ psychosocial condition after discharge was associated with their immigration status | Survey-based study Survey at university-affiliated hospital in Singapore |

Patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention, median symptom-to-balloon time, median door-to-balloon time and prescription of evidence-based medical therapy | Place of birth and citizenship (1) Singapore-born citizens (2) Foreign-born citizens (3) Permanent residents | Cardiovascular risk factor profile Admission pathway | Education level Occupation Average monthly household income | There were no major disparities in access to high quality health care for patients with different immigration status |

| Marchesini G et al. [43] 2014 |

Italy | 2010 | 7,856,348 patients Italy-born Italian citizens (n = 7,328,383) Foreign-born no Italian citizens (n = 527,965) All ages |

To assess whether prevalence, treatment and direct costs of drug-treated diabetes were similar in migrants and in people of Italian citizenship | Register-based study Administrative data sources of all Italian residents in 30 health districts (ARNO observatory) |

(1) Prescriptions (2) Hospitalizations (3) Healthcare services (consultations, laboratory tests and other diagnostic procedures) | Place of birth | Age & gender | Place of residence | Migrants show a higher risk of diabetes but less intense treatment |

| Pourat N et al. [44] 2014 |

USA (California) | 2009–2010 | 59,938 individuals Natives (n = 8602) Immigrants (n = 388) All ages | Test the validity of the assertion that undocumented immigrants are more frequent users of health care | Survey-based study California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) |

(1) Number of doctor visits in the past year (2) Percentage of respondents with an ED visits among children and adults in the past year (3) Percentage of children who had a doctor visit in the past year | (1) US-born (2) Naturalized citizen (3) Legal permanent resident or other authorized immigration status (4) Undocumented immigrants | Age & gender Ethnicity Self-assessed health status Number of chronic conditions |

Insurance coverage Official Employment status Household income Family status Family size Language (English) proficiency Region of residence Place of residence |

Utilization among undocumented immigrants in all analyses was lower than or similar to that of other groups |

| Ramos JM et al. [28] 2013 |

Spain (Alicante) | 2011 | 42,839 individuals Natives (n = 38,620) Immigrants (n = 4219) ≥15 years | To compare hospital admission rates, diagnoses at hospital discharge, service of admission at hospital discharge, and mortality between FCs and autochthonous citizens (ACs) | Register-based study Hospital discharges registries from hospital information systems (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante (HGUA) and Hospital Universitario de Sant Joan d’Alacant (HUS)) |

Hospital admissions | Foreign citizen (FC) (people without Spanish citizenship) (1) FCs from high income countries (born in 25 European Union countries, Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, the USA, Canada, Japan, and Australia) (2) FCs from low income countries (born elsewhere: North Africa and the Middle East, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia) |

Age & gender Diagnosis at discharge Unit of admission Destination at discharge Length of stay |

– | The utilization rate was lower in foreign citizens |

| Rucci P et al. [18] 2015 |

Italia (Bologna) | 2010–2011 | 8990 individuals Natives (n = 8602) Immigrants (n = 388) All ages | To determine whether disparities exist in mental healthcare provision to immigrants and natives with severe mental illness | Register-base study Information system of the Departments of Mental Health (DMH), Emilia-Romagna |

(1) Receiving psychosocial rehabilitation the following year (2) Days admitted to hospital wards or to residential facilities the following year | Citizenship (immigrants comprise regular immigrants, non-documented immigrants, no Italian citizenship) | Age & gender Mental illness diagnosis Age at first contact Duration of episode |

Education level Marital status Working status Living arrangement CMHC area |

Although the probability of receiving any mental health intervention is similar between immigrants and Italians, the number of interventions and the duration of admissions are lower for immigrants Immigrants spend less days of residential care in licensed psychiatric facilities or other facilities |

| Smith-Nielsen S et al. [45] 2015 |

Denmark | June–August 2007 | 3,573 individuals Natives (n = 1131) Labour immigrants (n = 808) RGE immigrants (n = 1634) 18–64 years |

To investigate whether potential differences exist in the use of private practicing psychiatrists and psychologists | Register and survey-based study Survey and registry study on health and health behaviour of individuals registered at the Danish Civil Registration System (CPR number) |

Use of psychiatrist or psychologist last year | Citizenship: (1) Ethnic Danes (at least one parent born in Denmark with Danish citizenship) (2) Immigrant (people residing in Denmark for a minimum of 3 years and born in a foreign country to parents without Danish citizenship) (RGC: Refugee Generating Countries: Turkey, Pakistan, Iraq, Iran, Lebanon, Syria, Somalia and Yugoslavia) |

Age & gender Mental health status Physical health symptoms |

Marital status Education level Employment status Household income Length of stay in Denmark Oral Danish proficiency |

Immigrants from RGC have similar or higher use of psychiatrists and psychologists in private practice when taking mental health into account Labour immigrants in general, except for women using psychiatrists, have lower use of psychiatrists and psychologists |

| Spinogatti F et al. [29] 2015 |

Italy | 2001–2010 | 139,775 individuals >17 years | To analyse the differences in mental health service utilization by immigrant and native populations | Register-base study Regional mental health information system Departments of Mental Health (DHM), Lombardy |

(1) Contact with psychiatric services (2) Hospitalization in acute psychiatric wards | Country of birth | Age & gender Mental disorder |

Marital status Education level Employment status |

The treated prevalence of native patients outnumbers that of immigrant ones, although immigrant patients use acute mental health services more frequently |

| Straiton M et al. [19] 2014 |

Norway | 2008 | 2,712,974 individuals Natives (n = 2,604,757) Immigrants (n = 108,217) 18–67 years | To explore treatment options in primary care for immigrant women with mental health problems compared with non-immigrant women | Register-base study National registries (1) National Population Register (2) Norwegian Health Economics Administration database-HELFO (3) Norwegian Prescription Database-NorPD |

PHC services (1) GP psychological consultations (2) EPC psychological consultation | Country of birth (1) Natives (born in Norway with both parents born in Norway) (2) Immigrants (born abroad with both parents from abroad) staying at least 6 months |

Age & gender GP and EPC non-psychological consultation |

Marital status Income level Length of stay Reason for migration Place of residence |

Overall, immigrants are less likely to use a GP or EPC services for mental health problems Immigrant women are somewhat underrepresented in PHC care services for mental health problems |

| Straiton ML et al. [20] 2016 |

Norway | 2008 | 1,283,437 individuals Natives (n = 1,230,175) Immigrants (n = 53,262) 20–67 years |

(1) To identify in which forms of treatment immigrant women are over or under represented compared with native Norwegians, and if this varied by country of origin (2) To determine whether use of an interpreter increases the likelihood of accessing different treatment types | Register-base study National registries (1) National Population Register (2) Norwegian Health Economics Administration database-HELFO (3) Norwegian Prescription Database-NorPD |

Mental health services (1) Conversational therapy (2) Psychiatric referrals (3) Psychotropic medication (4) Certificates for sickness leave and disability applications | Country of birth (1) Natives (born in Norway with both parents born in Norway) (2) Immigrants (born abroad with both parents from abroad) staying at least 6 months, divided according to the World Bank income categories of their country of origin |

Age Diagnosis Use of interpreter |

Marital status Income level Length of stay Place of residence |

Women are somewhat underrepresented in PHC services for mental health problems A higher percentage of Norwegian women had had a Psychiatric consultation than any of the 6 immigrant groups Psychiatric referral rates did not differ by country of origin |

| Tarraf W et al. [30] 2014 |

USA | 2000–2008 | 167,889 individuals US-born (n = 133,102) Naturalized FB-citizens (n = 14,338) Non-citizens (n = 20,449) ≥18 years | (1) Provide a detailed accounting of ED use with policy-relevant immigrant classifications (2) Examine associations between ED use and citizenship status using a Behavioural Model of healthcare access and utilization (3) Determine the most important factors associated with differences in immigrants’ ED services use | Survey-based study (1) Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) (2) National Health Interview Survey |

Self-reported past-year ED use | Immigration status and place of birth (1) US-born citizens (2) Naturalized foreign-born (FB) citizens (immigrants who have obtained US citizenship) (3) FB non-citizens (legal permanent residents, as well as undocumented and “other” immigrants) |

Age & gender Self-reported ethnicity/race Self-rated health Medical conditions Past-year healthcare provider visits Past-year hospital discharges |

Insurance status Usual source of care availability Education level Household income-to-poverty Place of residence (urbanity) Region | Immigrants, and particularly non-citizens, were less likely to use ED services Non-citizens are less likely to use ED services and showed that they are also less likely to be repeat users |

| Tormo MJ et al. [31] 2015 |

Spain (Murcia) | 2006–2008 | 2453 individuals Natives (n = 1303) Immigrants (n = 1303) 18–64 years | To describe the utilization of health services among immigrant and male and female native populations | Survey-based study (1) Spanish National Health Survey (SNHS) (2) Health and Culture Survey (SyC) |

(1) Unmet healthcare need in the last 12 months (2) Visit to a GP in the last year (3) Visit to dentist in the last year (4) Hospitalization and ED visit in the past year (5) Drug consumption it last 2 weeks | Immigrants with Health Insurance Card (Tarjeta Sanitaria Individual-TSI) | Age & gender Self-assessed health status Health problems last year Activity limitation last 2 weeks |

Education level Social class | Migrants showed a lower use of PHC services specialists, but a higher use of ED |

| Verhagen I et al. [32] 2014 |

Netherlands | 2010 | 68,214 individuals Natives (n = 33,725) Immigrants (n = 34,489) ≥55 years | To study whether healthcare use of the four ethnic minority elderly populations in the Netherlands varies from the ethnic Dutch elderly | Register-base study Registry data from the Achmea Health Insurance Company (Achmea) |

(1) GP services (2) Receipt of prescriptions (3) Physical therapy (4) Hospital services (5) Medical aids to help with a limitation | Country of birth or surname Turkish, Moroccan, Surinamese and Moluccan | Age & gender | Additional health insurance Neighbourhood deprived |

The use of PHC facilities (GP services and prescriptions) within most ethnic minority groups is higher; however, they generally make less use of hospital care, medical aids, and physical therapy |

| Villarroel N et al. [46] 2015 |

Spain | 2006 | 22,224 patients Natives (n = 20,226) Immigrants (n = 1998) 16–64 years | (1) To analyse differences in patterns of healthcare use (visits to PC, hospitalizations and emergency visits) between the native Spanish population and immigrants from the seven leading countries in terms of number of immigrants in Spain in 2006 (2) To examine whether the differences are explained by self-perceived health status, educational level, family characteristics, employment status and social support (3) To determine whether the patterns of association differ by gender | Survey-based study Spanish National Health Survey (SNHS) 2006–2007 |

(1) Visit to a GP in the 4 weeks before (2) Hospitalization in the past year (3) ED visits in the past year | Country of birth | Age & gender Self-perceived health status |

Marital status Educational level Employment status Social support (adapted from the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire) Social support (adapted from the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire) |

Immigrants made less than, or about the same use of healthcare services Among men, a lower use of healthcare services was found among those born in Romania for all healthcare levels and among Ecuadorians for hospitalizations Among women a lower use of PHC was found among those born in Argentina, Bolivia and Ecuador, and a higher use among Peruvians. No differences were observed with native-born subjects A higher utilization of healthcare services was only found among men born in Bolivia, who were more likely to use hospitalization |

| Wang L [47] 2014 |

Canada | 2005–2010 | 94,948 individuals Canadian-born (n = 73,806) Foreign born (n = 21,142) 18–75 years | Explore the relationships among individual socio-economic status, residential neighbourhood characteristics and self-reported health for multiple immigrant groups | Survey-based study Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) |

(1) Have a regular physician (2) Stay overnight in hospital (3) Number of dental visits per year (4) Number of physician visits per year | Country of birth, ethnic origin and immigrant status (1) Native born (2) Long-standing groups (Italian and Portuguese) (3) Recent groups (Chinese and South Asian) (4) Overall foreign born |

Age & gender Self-perceived health status Chronic diseases Health behaviour (smoke, overweight, physical activity, vegetable intake) | Marital status Education level Household income Language proficiency Length of stay Neighbourhood characteristics (deprivation & ethnic concentration) |

Immigrants have lower rates of overnight stay in hospital All four selected immigrant groups have higher rates for having a regular physician Immigrants report significantly more physician visits Foreign-born groups report fewer dental visits |

| Wang L et al. [48] 2015 |

Canada | 2005–2010 | 161,981 individuals Native born (n = 124,946) Korean immigrants (n = 351) Overall foreign born (n = 36,684) ≥25 years | To explore healthcare-seeking behaviour of South Korean immigrants in Toronto, Canada, and how transnationalism shapes post-migration health and health-management strategies | Survey-based study Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2005–2010 |

(1) Stay overnight in hospital (2) Physician visits (3) Dental visits | Country of birth (1) Native born in Canada (2) Overall foreign born (3) Korean immigrant | Age & gender Self-perceived health status Chronic diseases | Marital status Education level Employment status Household income Immigration category Length of stay Place of residence |

Of the three groups, Koreans use health services the least They have the lowest rate of having a regular doctor and overnight stay in hospital, the lowest numbers for dental and physician visits in the past 12 months, and the highest rate of no doctor visit in the past 12 months |

CMHC Community Mental Health Centers, ED emergency department, EPC emergency primary care, GP general practitioner, HIC high income country, LIC low income country, MIC medium income country, OHIP Ontario Health Insurance Plan, PHC primary health care, STMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

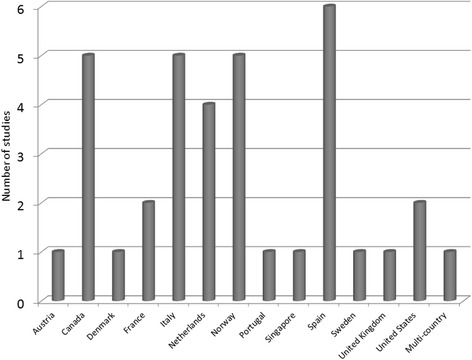

Distribution of studies regarding publication year was as follows: 8 studies published in 2013 [17, 22–24, 27, 28, 41, 42], 15 in 2014 [14–16, 19, 21, 30, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 43, 44, 47], 10 in 2015 [13, 18, 25, 26, 29, 31, 34, 45, 46, 48] and 3 in 2016 [20, 37, 39]. The majority of the publications analysed data from European countries (28; 78%), both North and Central (12) (Norway [13–15, 19, 20], Denmark [45], Sweden [35], the Netherlands [17, 32, 34, 40] and Austria [41]) and South Europe (15) (France [22, 36], Italy [18, 24, 29, 37, 43], Spain [23, 27, 28, 31, 38, 39, 46] and Portugal [33]) and 1 from the UK [26]. Seven papers (19%) explored this issue in North America (2 from USA [30, 34] and 5 from Canada [16, 21, 25, 47, 48]); and 1 (3%) in Asia (Singapore) [42] (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of studies according to country of destination

Geographical coverage of the studies has some variation: 21 performed at the national level [13–15, 17, 19–22, 28, 30, 32, 34–36, 38, 40, 41, 45–48], 10 at a regional level [16, 18, 23, 25–27, 29, 31, 37, 44], 3 at a local level [28, 33, 42] and 1 multi-country study [39] with data from a regional level of 1 country and the national level of the other. There were only 4 longitudinal studies (2 prospective [18, 42] and 2 retrospective [27, 43]) and 1 case-control study [35]. Sample sizes ranged from 74 [35] to 7,856,348 [43]. Multivariable regression (Poisson or logistic) was the most frequent analysis. Only 9 studies conducted univariate analysis [29, 32, 33, 35, 38, 43, 48].

Sources of information

Service utilization could be assessed from two perspectives: the physician’s perspective, based on recorded databases and volume of medical services, and the patient’s perspective, based on patient-reported use of services through healthcare surveys [49].

The largest number of papers (18) used information from administrative [13–16, 18–20, 23, 25, 29, 33, 35, 37, 39, 43] or insurance system databases [32, 34] and specific hospital registries [28] as source of information. Among the 16 papers (44.4%) that analysed healthcare surveys, where people report their individual healthcare use, 14 studies used population-based surveys which were elaborated for other purposes [17, 21, 22, 24, 26, 30, 36, 38, 40, 44, 46–48] while 3 of the surveys were specifically designed to explore immigrants healthcare use [31, 41, 42]. Only 2 studies [33, 45] (5.6%) combined health survey and administrative information and 1 study also used a national survey for general practitioners (GPs) [17].

Subjects

There were diverse definitions of immigrants. Country of birth was the most common criteria used to define immigrants (18), or country of birth of the subject and their parents (10). In addition, name recognition (2) [32, 34], citizenship (3) [18, 24, 28] or a combination of citizenship and country of birth (3) [30, 42, 45] were also used.

The majority of papers classified the immigrant population in sub-groups usually based on country of birth (13). However, some studies considered geographic area of origin (8) or World Bank categories of income level (5). Other less frequent categories considered were legal status (3), reason of migration (1), length of stay in the country (3) and being first of second generation (1). Only 2 studies (5.6%) [18, 22] compared the use of services considering the immigrant populations as a whole, without defining specific sub-groups in those populations.

Findings

The outcome “healthcare service utilization” could be organized in seven focus areas: primary care, specialist’s services, hospitalizations, emergency services, mental health, dental care and medication prescription. Some studies reported on more than one outcome. In total, 8 papers analysed the use of primary care (including GP visits, dental care and physiotherapy) [13–15, 21, 27, 36, 44, 48], 6 evaluated the use of specialist services (including hospitalizations or emergency care) [23, 28, 30, 33, 35, 42], 5 assessed mental health services [17, 18, 20, 29, 45], 10 evaluated the use of both primary care and specialists [22, 24, 31, 32, 34, 37, 38, 43, 46, 47], 2 evaluated primary care and mental health [19, 40], 4 evaluated both primary care, mental health and hospitalizations [16, 25, 26, 41] and 1 studied pharmaceutical use and prescriptions [39]. In addition, 6 studies also reported medication consumption [20, 31, 32, 37, 42, 43].

The measurement of healthcare utilization was either continuous (number of contacts) or dichotomic (having had any contact). The period of time used to determine utilization ranged from 4 weeks through 1 year.

The more frequent outcome was that immigrants have lower [17–20, 22, 25, 27, 28, 30, 33, 35, 40, 43, 44, 48] or similar [13, 21, 34, 36, 41, 42] healthcare utilization. However, studies that included analysis by sub-groups of immigrants identified some differences across groups [14–16, 23, 26, 31, 37, 39, 40, 45, 46] as well as with the type of service assessed [14, 24, 29, 31, 32, 38, 40, 46, 47].

The immigrant population showed a similar [23, 24, 29, 31, 32, 34, 36–40, 46] or lower [17, 18, 22, 27, 28, 33, 43] use of primary care and specialized care in countries with universal access to health care—even for undocumented migrants [50]. This finding was consistent regardless of the source of information used. In other countries, some differences were identified associated with the source of information: immigrants showed higher use of health services when estimates were based on surveys [26, 41, 45], while their rates were lower [19, 20, 35] or similar [13–15] when registries or administrative data were used.

Discussion

The main result of this review is that migrant populations appear to have a lower use of health services than native populations, with a similar level of use of primary care services. This result appears to be independent from differences in need of access. Nevertheless, the great heterogeneity of the studies included in this review, considering both the sources of information, as well as factors used for controlling health need and to classify immigrants in sub-groups, requires caution when making an overall estimation valid for all immigrants.

Different sources of heterogeneity should be mentioned. First, and probably the factor with the highest relevance, was the definition of immigrant and their characterization. This review has identified several factors that could be involved with differences in healthcare utilization among immigrants: income of the original native countries [13–15, 28, 38], the specific reasons motivating migration [15, 16, 19, 25, 26], fluency in the host country language [16, 17, 21, 25, 44, 45, 47] and length of time of stay [13, 15, 19–21, 26, 38, 45, 47, 48].

There were also differences in how medical need was determined and how to estimate factors that predispose to healthcare use. The majority of studies assessed health needs from the point of view of self-perceived health, and through commonly used socio-demographic variables, such as education, income or working status, following the model of Aday and Anderson [51, 52]. Multivariable models were adjusted by these variables to eliminate the effect they could have on utilization, but whether they had a differential influence on immigrants or native populations remains inconclusive.

Variables which could have a significant effect on healthcare service use and in particular for mental health care [53], such as health beliefs and cultural concepts on the part of the immigrants, fear of stigmatization, taboos, perceived efficacy of health interventions or use of alternative services, were usually not considered. The effect of these variables is most commonly explored through qualitative techniques, and papers that used those methods were not included in this report.

Variation in countries’ healthcare systems limits direct cross-country comparisons, although immigrants showed similar patterns of utilization in countries with significant differences in their healthcare services. Nevertheless, studies reviewed pay little attention to the structural and organizational dimensions of healthcare systems, other than reporting the specific conditions for accessing health services. One paper explored the influence of attitudes of professionals regarding immigrants [54], 2 studies assessed the reasons for unmet healthcare need [31, 38] while 2 underscored the patient workload of healthcare professionals [22, 23]. In addition, the effect that new legislation enacted in different countries could have had on access to healthcare services by immigrants has not yet been evaluated and published and therefore cannot be assessed in this review.

Attempting to expanding the scope of previous reviews, we tried not to constrain the inclusion criteria regarding areas of healthcare services assessed [10, 55, 56], context of the study (country) [54, 55], or characteristics of immigrants [54, 55].

This work adds also new information regarding the use of mental health services, both in terms of primary [19, 26] and specialized mental services [16–18, 20, 25, 29, 41, 45]. Nevertheless, and although immigrants have shown a higher susceptibility to emotional and mental health problems that could be linked to the stressors of adapting to the host country [57], those studies reported similar findings as for other health services: an overall lower use by migrants, also with differences across sub-groups and with an occasional higher use of emergency care.

This review also provides the opportunity to have an insight of the healthcare use of certain vulnerable sub-groups, as the handicapped [13], the elderly [13, 15, 32, 37] or patients with chronic conditions [21, 34, 36], but the pattern of use of those sub-groups is similar to that of the general population, even when immigrants seem to have less health problems than natives [13, 34], or a poorer health status [36]. Immigrants also showed a higher use associated with longer periods of stay in the host countries [15, 21] as well as significant differences of use among migrant sub-groups [32, 37].

The effect of gender differences was assessed most notably in papers evaluating the use of mental health services [16, 19, 20, 25, 41, 45]. Nevertheless, no conclusive evidence could be established: compared to their native counterparts, Straiton et al [19, 20] and Durbin et al [16, 25] found a lower use of mental health services for immigrant women, while Kerkenaar et al [41] and Smith-Nielsen et al. [45] found a higher use.

The possibility to analyse the use of different levels of care may help to determine the existence of gaps in utilization (less use in one area could explain an increased use in another area) or highlight the existence of different referral criteria (primary care specialists) [23]. De Luca et al. found [24] an over-utilization of emergency services associated with an under-utilization of preventive care services among the immigrant population. Tormo et al. [31] and Díaz et al. [14] obtained similar results, although they concluded that the higher use of emergency services did not compensate the lower use of GPs. The identification of differences in pharmaceutical consumption could also lead to identify particular health problems or economic barriers accentuated by the development of restrictive health policies.

Lastly, the large number of European studies, particularly from western and central Europe, has to be highlighted, probably depicting the interest about the migratory pressure these countries have faced in the last years—migration from Eastern Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain; from Latin America, North and sub-Saharan Africa; from internal migration flows south-north after the economic crisis; or most recently, the refugee crisis.

Study limitations

The literature search was conducted only in one database (MEDLINE), although the electronic search was manually completed using Google Scholar. There were implied limitations in the manual search, since it was not systematized and was susceptible to errors as it relied on title appropriateness (particularly for articles with ambiguous titles). Furthermore, no backward citation of the papers included in the systematic review was performed. Additionally, the systematic search only identified 50% of the papers accepted for inclusion, which raises some doubts regarding the intrinsic limitations of the system to classify and assign terms to papers that compare the use of healthcare services between native and migrants.

Finally, qualitative papers that explored the use of healthcare services were not included, as it would be difficult to draw comparisons from these studies.

Conclusions

Overall, and regardless of the changes in the immigration process, data here analysed is coincident with results obtained in previous reviews [10, 54, 56], confirming that immigrants show a general tendency to a lower use of health services than native populations. But these data also indicate the existence of differences within the immigrant populations, reinforcing the conclusion that further studies intended to compare the rate of healthcare use between native and immigrant populations should incorporate information that allows for better identification and characterization of the immigrant population. The immigrant population cannot be considered as a uniform whole. Their diversity has to be taking into account when describing and analysing their healthcare utilization. This will also require improvement and standardization of the information collected [55, 58].

In this sense, the limitations of health surveys have to be emphasized. Surveys are not just subjected to memory bias, but they are less suited to be representative of all relevant sub-groups of the immigrant population, as their samples usually do not include enough participants to reflect the wide variability of the diverse immigrant population to estimate their differential use. For instance, only one paper includes immigrants in irregular status [44]. Therefore, the use of data that overcome these limitations has to be encouraged. Further studies should be based on other information, such as registers, administrative or insurance data, or data from non-governmental organizations [59].

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by the Institute of Health Carlos III and REDISSEC Thematic Network.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

ASS was the principal investigator who contributed to the conception and design of the study; collected, entered, analysed and interpreted the data; led the paper and acted as corresponding author. AIHG collected, entered, analysed and interpreted the data and prepared the manuscript. LAGF contributed to data analysis and interpretation and drafted the manuscript, and RC participated in the conception and design of the study and helped to draft the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CMHC

Community Mental Health Centers

- ED

Emergency department

- EPC

Emergency primary care

- GP

General practitioner

- HIC

High income country

- LIC

Low income country

- MIC

Medium income country

- OHIP

Ontario Health Insurance Plan

- PHC

Primary health care

- STMI

ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

Contributor Information

Antonio Sarría-Santamera, Phone: +34-91-822-2020, Email: asarria@isciii.es.

Ana Isabel Hijas-Gómez, Email: aihijas@fhalcorcon.es.

Rocío Carmona, Email: rocio.carmona@isciii.es.

Luís Andrés Gimeno-Feliú, Email: lugifel@gmail.com.

References

- 1.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. International Migration Report 2015: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/375). 2016. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2015_Highlights.pdf. Accessed 22 Jul 2016

- 2.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2013) International Migration Report 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rechel B, Mladovsky P, Ingleby D, Mackenbach JP, McKee M. Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1235–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemminki K. Immigrant health, our health. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:92–95. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Real Decreto-ley 16/2012, de 20 de abril, de medidas urgentes para garantizar la sostenibilidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud y mejorar la calidad y seguridad de sus prestaciones. Madrid: Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (April 20, 2012). https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2012-5403. Accessed 9 Mar 2016 [Article in Spanish]

- 6.Immigration Act 2014 c.22. UK Parliament. London: The Stationery Office (May 14, 2014). http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/22/contents/enacted. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

- 7.Public Law 111–148. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 111th United States Congress. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office (March 23, 2010). https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/PLAW-111publ148/PLAW-111publ148/content-detail.html. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

- 8.Villalonga-Olives E, Kawachi I. The changing health status of economic migrants to the European Union in the aftermath of the economic crisis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:801–803. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-203869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronda-Pérez E, Ortiz-Barreda G, Hernando C, Vives-Cases C, Gil-González D, Casabona G. Características generales de los artículos originales incluidos en las revisiones bibliográficas sobre salud e inmigración en España. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2014;88:675–685. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272014000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmona R, Alcazar-Alcazar R, Sarria-Santamera A, Regidor E. Frecuentación de las consultas de medicina general y especializada por población inmigrante y autóctona: una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2014;88:135–155. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272014000100009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Béland F. Utilization of health services as events: an exploratory study. Health Serv Res. 1988;23. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.European Commission. EU Immigration portal. Glossary. 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/immigration/glossary_en. Accessed: 22 Jul 2016.

- 13.Diaz E, Kumar BN, Engedal K. Immigrant patients with dementia and memory impairment in primary health care in Norway: a national registry study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;39:321–331. doi: 10.1159/000375526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Díaz E, Calderón-Larran A, Prado-Torres A, Poblador-Plou B, Gimeno-Feliú LA. How do immigrants use primary health care services? A register-based study in Norway. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:72–78. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz E, Kumar BN. Differential utilization of primary health care services among older immigrants and Norwegians: a register-based comparative study in Norway. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:623. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0623-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durbin A, Lin E, Moineddin R, Steele LS, Glazier RH. Use of mental health care for nonpsychotic conditions by immigrants in different admission classes and by refugees in Ontario, Canada. Open Med. 2014;8:e136–e146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koopmans GT, Uiters E, Deville W, Foets M. The use of outpatient mental health care services of migrants vis-à-vis Dutch natives: Equal access? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:342–350. doi: 10.1177/0020764012437129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rucci P, Piazza A, Perrone E, Tarricone I, Maisto R, Donegati I, et al. Disparities in mental health care provision to immigrants with severe mental illness in Italy. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24:341–352. doi: 10.1017/S2045796014000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straiton M, Reneflot A, Diaz E. Immigrants’ use of primary health care services for mental health problems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:341. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Straiton ML, Powel K, Reneflot A, Diaz E. Managing Mental Health Problems Among Immigrant Women Attending Primary Health Care Services. Health Care Women Int. 2016;37:118–139. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2015.1077844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beiser M, Hou F. Chronic health conditions, labour market participation and resource consumption among immigrant and native-born residents of Canada. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:541–547. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0544-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berchet C. Health care utilisation in France: An analysis of the main drivers of health care use inequalities related to migration. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2013;61(Suppl 2):S69–S79. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carmona-Alférez MR. Derivaciones a especialistas en atención primaria según lugar de nacimiento de los pacientes (Doctoral thesis). Facultad de Medicina. Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2013). http://eprints.ucm.es/24295/ Accessed 17 Mar 2016. [Article in Spanish]

- 24.De Luca G, Ponzo M, Rodriguéz Andrés A. Health care utilization by immigrants in Italy. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2013;13:1–31. doi: 10.1007/s10754-012-9119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durbin A, Moineddin R, Lin E, Steele LS, Glazier R. Mental health service use by recent immigrants from different world regions and by non-immigrants in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:336. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazard B, Frissa S, Nellmus L, Hotopf M, Hatch SL. Challenges in researching migration status, health and health service use: an intersectional analysis of a South London community. Ethn Health. 2015;20:564–593. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.961410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gimeno-Feliú LA, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Prados-Torres A, Revilla-López C, Diaz E. Patterns of pharmaceutical use for immigrants to Spain and Norway: a comparative study of prescription databases in two European countries. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15:32. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0317-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos JM, Navarrete-Muñoz EM, Pinargote H, Sastre J, Seguí JM, Rugero MJ. Hospital admissions in Alicante (Spain): a comparative analysis of foreign citizens from high-income countries, immigrants from low-income countries, and Spanish citizens. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:510. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spinogatti F, Civenti G, Conti V, Lora A. Ethnic differences in the utilization of mental health services in Lombardy (Italy): an epidemiological analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:59–65. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0922-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarraf W, Vega W, González HM. Emergency Department Services Use among immigrant and non-immigrant Groups in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16:595–606. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9802-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tormo MJ, Salmerón D, Colorado-Yohar S, Ballesta M, Dios S, Martínez-Fernández C, et al. Results of two surveys of immigrants and natives in Southeast Spain: health, use of services, and need for medical assistance. Salud Publica Mex. 2015;57:38–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verhagen I, Ros WJG, Steunenberg B, Laan W, de Wit NJ. Differences in health care utilisation between elderly from ethnic minorities and ethnic Dutch elderly. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:125. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almeida LM, Santos CC, Caldas JP, Ayres-de-Campos D, Sias S. Obstetric care in a migrant population with free access to health care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126:244–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Back TR, Bodewes AJ, Brewster LM, Kunst AE. Cardiovascular Health and Related Health Care Use of Moluccan-Dutch Immigrants. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esscher A, Binder-Finnema P, Bødker B, Högberg U, Mulic-Lutvica A, Essén B. Suboptimal care and maternal mortality among foreign-born women in Sweden: maternal death audit with application of the “migration three delays” model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fosse-Edorh S, Fagot-Campagna A, Detournay D, Bihan H, Gautier A, Dalichampt M, Druet C. Type 2 diabetes prevalence, health status and quality of care among the North African immigrant population living in France. Diabetes Metab. 2014;40:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franchi C, Baviera M, Sequi M, Cortesi L, Tettamanti M, Roncaglioni MC, et al. Comparison of Health Care Resource Utilization by Immigrants versus Native Elderly People. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]