Abstract

Background

Studies conflict on whether the duration of use of the copper intrauterine device is longer than that of the levonorgestrel intra-uterine device, and whether women who continue using intrauterine devices differ from those who discontinue.

Objective

We sought to assess continuation rates and performance of levonorgestrel intrauterine devices compared with copper intrauterine devices over a 5-year period.

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of 1164 individuals who underwent intrauterine device placement at an urban academic medical center. The analysis focused on a comparison of continuation rates between those using levonorgestrel intrauterine device and copper intrauterine device, factors associated with discontinuation, and intrauterine device performance. We assessed the differences in continuation at discrete time points, pregnancy, and expulsion rates using χ2 tests and calculated hazard ratios using a multivariable Cox model.

Results

Of 1164 women who underwent contraceptive intrauterine device insertion, 956 had follow-up data available. At 2 years, 64.9% of levonorgestrel intrauterine device users continued their device, compared with 57.7% of copper intrauterine device users (P = .11). At 4 years, continuation rates were 45.1% for levonorgestrel intrauterine device and 32.6% for copper intrauterine device (P < .01), and at 5 years continuation rates were 28.1% for levonorgestrel intrauterine device and 23.8% for copper intrauterine device (P = .33). Black race, primiparity, and age were positively associated with discontinuation; education was not. The hazard ratio for discontinuation of levonorgestrel intrauterine device compared with copper intrauterine device >4 years was 0.71 (95% confidence interval, 0.55–0.93) and >5 years was 0.82 (95% confidence interval, 0.64–1.05) after adjusting for race, age, parity, and education. Copper intrauterine device users were more likely to experience expulsion (10.2% copper intrauterine device vs 4.9% levonorgestrel intrauterine device, P < .01) over the study period and to become pregnant in the first year of use (1.6% copper intrauterine device vs 0.1% levonorgestrel intrauterine device, P < .01).

Conclusion

We found a difference in continuation rates between levonorgestrel and copper intrauterine device users at 4 years but not at 5 years. Copper intrauterine device users were more likely to experience expulsion and pregnancy.

Keywords: copper intrauterine device, intrauterine device, intrauterine device continuation, levonorgestrel intrauterine device, long-acting reversible contraception

Introduction

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are highly effective long-acting reversible contraceptives.1,2 Their use in the United States has increased in recent years, rising from 8.5% in 2009 to 11.6% in 2012.3 IUDs are highly cost-effective contraceptives.4 Given their high efficacy, ease of use, and cost-effectiveness, IUDs have great potential to prevent undesired pregnancy5 and to allow women to exercise autonomy over their reproductive health.

In the United States, IUDs are available in 2 formulations: the copper (Cu)-IUD and the levonorgestrel (LNG)-IUD. Cu-IUDs are labeled for 10 years of use but may be used for 12 years.6 One type of LNG-IUD (Mirena, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Whippany, NJ) is labeled for 5 years; some evidence suggests Mirena can be used for 7 years.6 Three other types of LNG-IUD (Skyla, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Liletta, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Petah Tikva, Israel, and Kyleena, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc.), newly available, are labeled for 3-5 years of use.

Several studies have compared the duration of use of the Cu-IUD with that of the LNG-IUD. One study in several European countries, published in 1994, randomized women to either the Cu-IUD or the LNG-IUD and found that continuation rates were similar between the 2 groups, with 5-year continuation rates of 44.5% for the Cu-IUD and 46.9% for the LNG-IUD.7 Another study conducted in the United States, published in 2015, similarly found no difference in continuation rates between IUDs, with 62.3% of LNG-IUD users and 64.2% of Cu-IUD users continuing at 4 years.8 However, a third study published in 1990 and conducted in multiple countries that randomized women to the LNG-IUD or Cu-IUD found that continuation was higher among Cu-IUD users than LNG-IUD users, with 40.6% in the Cu-IUD group continuing at 5 years compared with 33.0% in the LNG-IUD group.9

Women who continue IUD use may differ from those who discontinue. One study found that nulliparous women were more likely to discontinue their IUDs10; another did not find such an association, but did find that women <24 years of age and those with a history of a sexually transmitted infection were more likely to discontinue, while those age >29 years were less likely to discontinue.8 A third study that followed up women for 6 months found no association between discontinuation and age, race, or parity.11

We sought to compare IUD continuation rates between the LNG-IUD (Mirena) and the Cu-IUD (ParaGard, Teva Pharmaceuticals) among women who received care at an academic medical center to understand characteristics associated with continuation or discontinuation, and to estimate pregnancy and expulsion rates for the 2 types of IUDs.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study investigating continuation rates of IUDs placed at an urban academic medical center. We included all women who had IUDs placed for contraceptive purposes in resident or faculty clinics or the operating room at an urban medical center in Boston, MA, from May 2006 through January 2011. We included follow-up data available through February 2016 to allow for at least 5 years of follow up for IUDs inserted in January 2011. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

We reviewed the medical records of all individuals who met eligibility criteria. We abstracted data about continuation or discontinuation of the IUD, including notes from all medical services and radiology reports. Participants were assigned a discontinuation date based on the date of IUD removal, date of absence in clinical notes, or date of absence on radiological exam. Women who had an IUD removed or expelled and had a reinsertion, either on the same day or at a later date, were considered to have discontinued on the date of removal or expulsion. When the exact discontinuation date was not available, we estimated the date as the midpoint between the last known date of continuation and the first recorded date of discontinuation (either the date discontinuation was first noted in the chart or the date the device was not seen on radiological exam). Those who did not discontinue were assigned a continuation date based on the last time the method was mentioned in the medical record or noted on a radiological study. IUDs expelled or removed due to pregnancy were considered discontinued, as were those removed due to expiration. We followed up women until the date of discontinuation, 5 years after IUD insertion, or January 2016, whichever came first.

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture, a secure, web-based electronic data capture tool.12 We used frequency, percentage, mean with SD, and median with interquartile range (IQR) or 95% confidence interval (CI) to describe patient characteristics and duration of IUD use. Medians were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. We used χ2 tests to assess differences in continuation rates at 2, 3, 4, and 5 years. A Kaplan-Meier survival function was calculated, and the curves were compared with the log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR). Variables for multivariable analysis were selected a priori, based on published research, and included race, age, parity, and education level. Potential confounding variables were included in the adjusted model regardless of their effect on the estimate. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant and all tests were 2-sided. Analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and Stata (Version 14.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

From May 2006 through January 2011, 1322 individuals underwent IUD placement, of whom 1164 had their IUD inserted for contraceptive purposes; 937 (80.5%) were LNG-IUDs and 227 (19.5%) were Cu-IUDs. Follow-up information was available for 956 (82.1%), 770 with LNG-IUD and 186 with Cu-IUD; the remaining 208 women either had no clinic visits after insertion or had no visits at which the IUD was mentioned. Women with follow-up were similar with respect to age, parity, education, race/ethnicity, and timing of insertion to those without; therefore, the analysis is restricted to the 956 patients with follow-up. Mean age at IUD placement was 32.2 years; 49.1% were white, 27.4% were black, 12.8% were Latina, 6.3% were Asian, and 4.5% were of other or unknown race/ethnicity (percentages exceed 100% due to rounding). The majority of insertions (64.5%) were interval insertions and the majority (59.8%) were inserted in faculty clinics. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1, stratified by IUD type.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by intrauterine device type.

| Characteristic | All n = 956 | LNG-IUD n = 770 | Cu-IUD n = 186 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at insertion, y | 32.2 ±6.6 | 32.1 ±6.6 | 32.8 ± 6.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 60 (6.3) | 43 (5.6) | 17 (9.1) |

| Black | 262 (27.4) | 224 (29.1) | 38 (20.4) |

| Latina | 122 (12.8) | 98 (12.7) | 24 (12.9) |

| White | 469 (49.1) | 376 (48.8) | 93 (50) |

| Unknown/other | 43 (4.5) | 29 (3.8) | 14 (7.5) |

| Parity | |||

| 0 | 194 (20.3) | 145 (18.8) | 49 (26.3) |

| 1 | 262 (27.4) | 215 (27.9) | 47 (25.3) |

| ≥2 | 485 (50.7) | 399 (51.8) | 86 (46.2) |

| Unknown | 15 (1.6) | 11 (1.4) | 4 (2.2) |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 27 (2.8) | 19 (2.5) | 8 (4.3) |

| High school | 160 (16.7) | 135 (17.5) | 25 (13.4) |

| Some college | 161 (16.8) | 130 (16.9) | 31 (16.7) |

| ≥College | 471 (49.3) | 370 (48.1) | 101 (54.3) |

| Other/missing | 137 (14.3) | 116 (15.1) | 21 (11.3) |

| Timing of insertion | |||

| Interval | 617 (64.5) | 478 (62.1) | 139 (74.7)a |

| Postpartum visit | 295 (30.9) | 257 (33.4) | 38 (20.4) |

| Postabortion | 39 (4.1) | 31 (4.0) | 8 (4.3) |

| Unknown/other | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Location of insertion | |||

| Faculty clinic | 572 (59.8) | 471 (61.2) | 101 (54.3) |

| Resident clinic | 355 (37.1) | 276 (35.8) | 79 (42.5) |

| Operating room | 26 (2.7) | 20 (2.6) | 6 (3.2) |

| Other/missing | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 0 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

CU, copper; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel.

One interval insertion was for emergency contraception.

Median follow-up was 795 days (IQR 229-1764) for both IUDs together. Median follow-up for LNG-IUD was 889 days (IQR 240-1790) and for Cu-IUD was 569 days (IQR 149-1281) (P < .01). At 2 years, 64.9% of individuals continued the LNG-IUD compared with 57.7% of Cu-IUD users (P = .11). At 3 years, 54.7% of individuals continued the LNG-IUD compared with 41.2% of Cu-IUD users (P < .01). At 4 years, 45.1% of LNG-IUD users continued, compared with 32.6% of Cu-IUD users (P < .01). At 5 years, 28.1% of LNG-IUD users continued, compared with 23.8% of Cu-IUD users (P = .33) (Table 2). Median duration of use was 3.66 (95% CI, 3.26–4.21) years [3.95 (95% CI, 3.33–4.58) years for LNG-IUD; 2.84 (95% CI, 2.40–3.51) years for Cu-IUD].

Table 2. Intrauterine device continuation at 2, 4, and 5 years.

| Continuation status | All | LNG-IUD | Cu-IUD | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2y | .11 | |||

| Continued | 491 (63.6) | 412 (64.9) | 79 (57.7) | |

| Discontinued | 281 (36.4) | 223 (35.1) | 58 (42.3) | |

| Total | 772 | 635 | 137 | |

| 3y | <.01 | |||

| Continued | 390 (52.3) | 336 (54.7) | 54 (41.2) | |

| Discontinued | 355 (47.7) | 278 (45.3) | 77 (58.8) | |

| Total | 745 | 614 | 131 | |

| 4y | <.01 | |||

| Continued | 307 (42.9) | 265 (45.1) | 42 (32.6) | |

| Discontinued | 409 (57.1) | 322 (54.9) | 87 (67.4) | |

| Total | 716 | 587 | 129 | |

| 5y | .33 | |||

| Continued | 187 (27.3) | 158 (28.1) | 29 (23.8) | |

| Discontinued | 498 (72.7) | 405 (71.9) | 93 (76.2) | |

| Total | 685 | 563 | 122 |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise notes and exclude those lost to follow-up at each time point.

CU, copper; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel.

P compares continuation rates between LNG-IUD and Cu-IUD users.

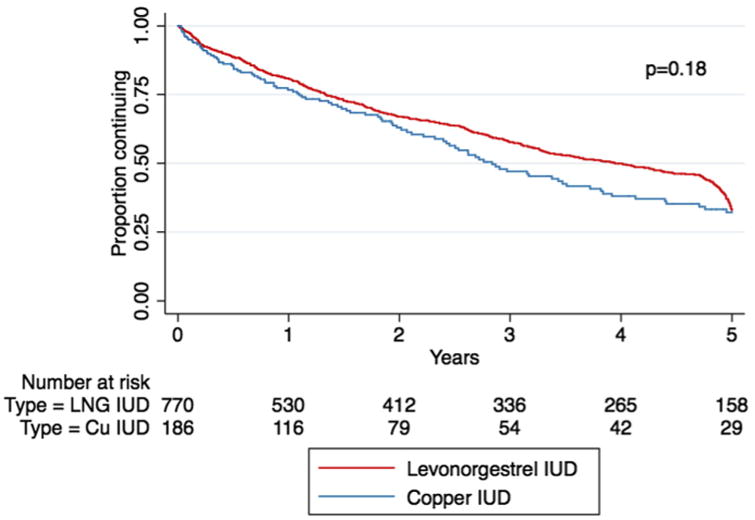

The Figure shows the Kaplan-Meier survival estimate over 5 years of follow-up, stratified by IUD type. No difference was found in the survival estimate between the groups at 5 years (P = .18). The HR for IUD discontinuation was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.69–1.08) for LNG-IUD users compared with Cu-IUD users (Table 3); adjusting for race, age, parity, and education did not significantly alter the estimate (adjusted HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.64–1.05). Black women were more likely to discontinue than white women. Women who had 1 child were more likely to discontinue compared with those who had ≥2 children. Those aged 21-29 years were more likely to discontinue compared with those aged ≥30 years. There was no significant difference in continuation by education.

Figure. Discontinuation over time, by intrauterine device type.

CU, copper; LNG, levonorgestrel.

Table 3. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios for intrauterine device discontinuation.

| Characteristic | Crude hazard ratio | Adjusted hazard ratio |

|---|---|---|

| IUD type | ||

| LNG-IUD | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) | 0.82 (0.64–1.05)a |

| Cu-IUD | Reference | Reference |

| Race | ||

| Black | 1.34 (1.09–1.64) | 1.31 (1.03–1.67)b |

| Latina | 1.16 (0.88–1.52) | 1.14 (0.84–1.55)b |

| Other/unknown | 1.07 (0.77–1.48) | 1.12 (0.79–1.61)b |

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Age, y | ||

| <21 | 1.40 (0.88–2.02) | 1.49 (0.87–2.52)b |

| 21–29 | 1.40 (1.17–1.69) | 1.44 (1.15–1.81)b |

| ≥30 | Reference | Reference |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) | 0.82 (0.60–1.13)c |

| 1 | 1.63 (1.34–1.98) | 1.35 (1.08–1.68)c |

| ≥2 | Reference | Reference |

| Education | ||

| ≤High school | 1.30 (1.04–164) | 1.15 (0.90–1.48)d |

| Some college | 1.24 (0.99–1.60) | 1.13 (0.87–1.45)d |

| ≥College | Reference | Reference |

CU, copper; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, age, parity, and education

Adjusted for IUD type, parity, and education

Adjusted for IUD type, race/ethnicity, age, and education

Adjusted for IUD type, race/ethnicity, and parity.

Given that 32.6% of women who discontinued their LNG-IUD due to expiration did so before the end of year 5, we also conducted analyses that censored women at 4 and 4.5 years; the HR comparing LNG-IUD users with Cu-IUD users at 4 and 4.5 years were 0.76 (95% CI, 0.60–0.96) and 0.77 (95% CI, 0.61–0.97), respectively. Adjusting for race, age, parity, and education did not change the results (adjusted HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.93 and 0.72, 95% CI, 0.56–0.93, respectively).

Of 554 LNG-IUD users who discontinued use, 33.0% did so due to expiration of the IUD, 12.8% due to desiring fertility, 11.4% due to abdominal or pelvic pain, 7.4% due to expulsion, 5.6% due to a change in bleeding pattern, and 29.8% discontinued for other or unknown reasons. Of 100 Cu-IUD users who discontinued use, 20.0% did so due to expulsion, 18.0% due to change in bleeding pattern, 15.0% due to desiring fertility, 8.0% due to abdominal or pelvic pain, and 39.0% discontinued for other or unknown reasons.

After discontinuing their IUD, 34.6% of participants elected to use the LNG-IUD, 17.8% selected no method, 10.5% used a combined hormonal contraceptive, 6.3% changed to barrier methods, 6.8% opted for sterilization, 2.0% chose the Cu-IUD, 3.5% started the etonogestrel implant, 3.7% started depot medroxyprogesterone acetate or progestin-only pills, and 14.9% chose other or unknown methods. Among those women whose LNG-IUD expired, 84.5% elected to have another inserted. Our follow-up time was 5 years, so none of the Cu-IUDs expired.

A total of 4.9% of LNG-IUDs were expelled during the study period, compared with 10.2% of Cu-IUDs (P < .01) (Table 4). Expulsion was not associated with parity, age <21 years, postpartum/postabortion timing of insertion, or provider training level (resident vs attending). Median time to expulsion was 112 days (IQR 45-399). In the first year of use, pregnancy rate in the LNG-IUD group was 0.1% compared with 1.6% in the Cu-IUD group (P < .01) among women who either became pregnant with the IUD in situ or had an unrecognized expulsion. Over the duration of follow-up, there were 7 pregnancies (3.8%) in the Cu-IUD group and 1 (0.1%) in the LNG-IUD group (P < .001).

Table 4. Characteristics related to expulsion.

| Characteristic | Expelled, % | P |

|---|---|---|

| IUD type | <.01 | |

| LNG-IUD | 4.9 | |

| Cu-IUD | 10.2 | |

| Parity | .46 | |

| 0 | 4.1 | |

| 1 | 6.9 | |

| ≥2 | 6.0 | |

| Age, y | .88 | |

| <21 | 5.4 | |

| ≥21 | 6.0 | |

| Timing of insertion | .40 | |

| Postpartum/ postabortion | 5.1 | |

| Interval | 6.5 | |

| Provider training level | .37 | |

| Resident | 7.0 | |

| Attending | 5.7 |

CU, copper; IUD, intrauterine device; LNG, levonorgestrel.

Comment

We found no difference in continuation rates when comparing the LNG-IUD with the Cu-IUD at 5 years, but this likely reflects slightly early replacement of devices due to expiration as we did find a difference at 4 and 4.5 years. Long-term continuation rates were low overall, with only 42.9% of IUD users continuing at 4 years and 27.3% at 5 years.

In terms of comparing continuation, our results contrast with 2 prior studies7,8 that found similar rates between IUDs, and with a third study that found higher continuation among Cu-IUD users.9 Our study differed from other research in that continuation rates overall were lower than reported in previous studies,7-9 one of which found 4-year continuation rates>60%.8 We hypothesize that the low rate seen in our study may more closely represent true continuation in clinical practice, outside of the structured setting of a randomized controlled trial or a contraceptive provision study with extensive counseling.13 Another possible explanation for the high discontinuation rate is our relatively high loss to follow-up; those who discontinued may have been more likely to present for continuing care than those who did not, and therefore would have been more likely to be captured in our retrospective study. Finally, our participants were older than participants in 2 of the other studies,8,9 which may contribute to our disparate findings; although we did find that older participants were less likely to discontinue.

In a study assessing IUD continuation at 6 months, individuals who received method-specific counseling were less likely to discontinue their device early.11 Discontinuation of contraceptive methods is inversely associated with method satisfaction14; giving more information about anticipated side effects of the LNG-IUD has been shown to improve user satisfaction with the device.15 Therefore, continuation rates may be higher in the setting of improved counseling. Our findings suggest that better counseling about IUDs may be necessary in the standard clinic setting.

We found first-year pregnancy rates of 0.1% and 1.6%, and overall expulsion rates of 4.9% and 10.2%, in the LNG-IUD and Cu-IUD users, respectively. Our finding of increased first-year pregnancy rates in the Cu-IUD group compared with the LNG-IUD group is consistent with other studies; first-year pregnancy rate for the LNG-IUD has been reported as 0.2%, and for the Cu-IUD as 0.8%.2 One prior study similarly found the expulsion rate for Cu-IUD to be higher than LNG-IUD16; another found similar expulsion rates between the 2 devices.7

Given the retrospective study design, we were limited to data available in the medical record; thus, we did not know the reasons for discontinuation for many of the women. In addition, loss to follow up was high. Although some follow up was available on 82.1% of women who had an IUD placed, some were followed for only a short amount of time. Another limitation of this study was the lack of information on exact date of IUD discontinuation for some patients. We addressed this by imputing a discontinuation date, which may lead to imprecision.

Strengths of this study include a large sample size, long duration of follow-up, a diverse population of women, and the inclusion of both resident and faculty practices. Our results may reflect real-world practice more than other studies on this topic. Additionally, we used documented discontinuation dates rather than patient report.

IUDs are highly effective contraceptives that are easy to use and provide excellent protection against pregnancy. Although continuation rates in this study were somewhat lower than shown in some prior studies, we found a median use of >3 years. Modeling studies have shown that IUDs become among the most cost-effective methods after 3 years of use4; therefore, even with the typical use seen in our study, IUDs are still among the most cost-effective contraceptive methods. Continued efforts to increase uptake and continuation of IUDs will improve women's ability to control their reproduction and result in cost savings for the health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Katherine Barnes, MD, and Kristin Hung, MD, who assisted with data abstraction.

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst/Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers. The funding source had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Presented as an abstract at the North American Forum on Family Planning, Denver, CO, Nov. 5-7, 2016.

References

- 1.Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, Do Minh T. Comparative contraceptive effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing and copper in-trauterine devices: the European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:280–3. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, Finer LB. Changes in use of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods among US women, 2009-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:917–27. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trussell J, Hassan F, Lowin J, Law A, Filonenko A. Achieving cost-neutrality with long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Contraception. 2015;91:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal PD, Voedisch A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy: increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:121–37. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmq026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson K, Odlind V, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use: a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 1994;49:56–72. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)90109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diedrich JT, Madden T, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Long-term utilization and continuation of intra-uterine devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:822.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivin I, el Mahgoub S, McCarthy T, et al. Long-term contraception with the levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day (LNg 20) and the copper T 380Ag in-trauterine devices: a five-year randomized study. Contraception. 1990;42:361–78. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(90)90046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham M, Zhao Q, Peipert JF. Young age, nulliparity, and continuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:823–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbers S, Haines-Stephan J, Lipton Y, Meserve A, Spieler L, Chiasson MA. Continuation of copper-containing intrauterine devices at 6 months. Contraception. 2013;87:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madden T, Mullersman JL, Omvig KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF. Structured contraceptive counseling provided by the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. Contraception. 2013;88:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreau C, Cleland K, Trussell J. Contraceptive discontinuation attributed to method dissatisfaction in the United States. Contraception. 2007;76:267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backman T, Huhtala S, Luoto R, Tuominen J, Rauramo I, Koskenvuo M. Advance information improves user satisfaction with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:608–13. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01764-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoun J, Dines VA, Stovall DW, Mete M, Nelson CB, Gomez-Lobo V. Effects of age, parity, and device type on complications and discontinuation of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:585–92. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]