Abstract

Transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) cation channels are poly-modal sensors that are involved in a variety of physiological processes. Within the TRPM family, member 8 (TRPM8) is the primary cold- and menthol-sensor in humans. We determined the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the full-length TRPM8 from the collared flycatcher at an overall resolution of ~4.1 Å. Our TRPM8 structure reveals a three-layered architecture. The amino-terminal domain with a fold distinct among known TRP structures, together with the carboxyl-terminal region, forms a large two-layered cytosolic ring that extensively interacts with the transmembrane channel layer. The structure suggests that the menthol binding site is located within the voltage-sensor-like domain and thus provides a structural glimpse of the design principle of the molecular transducer for cold and menthol sensation.

The transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) family, part of the TRP protein superfamily, is composed of eight members, TRPM1-TRPM8, and is involved in various processes including temperature sensing, ion homeostasis, and redox sensing (1, 2). The TRPM8 channel cDNA was cloned and characterized as the long-sought-after cold- and menthol-sensor (3, 4). Studies of TRPM8-deficient mice showed that the channel is required for environmental cold sensing (5–7), and that it is the principal mediator of menthol-induced analgesia of acute and inflammatory pain (8). Therefore, TRPM8 is a therapeutic target for treatments of cold-related pain, chronic pain, and migraine (9, 10).

In addition to cold and menthol, TRPM8 is sensitive to voltage and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) (11, 12). The molecular landscape of channel sensitization is shaped by the interplay between these four factors, suggesting that TRPM8 is a polymodal sensor that can integrate multiple chemical and physical stimuli into cellular signaling (11, 13). Several thermodynamic models have been put forth to address the mechanism of polymodal sensing by TRPM8 (14–16), but our mechanistic understanding of polymodal sensing by TRPM8 remains limited.

All members of the TRPM family contain a large N-terminal region (~700 amino acids) that comprises four regions of high homology (Melastatin Homology Regions, MHRs) (1). These MHR domains appear to be important for channel assembly and trafficking, but their functional roles are not known (17). TRPM8 was also predicted to contain a putative C-terminal coiled coil that is important for channel assembly, trafficking, and function (17, 18).

Extensive electrophysiological and biochemical studies have identified residues involved in ligand binding, and homology models have attempted to provide a structural context for their locations (19–22). However, in the absence of a structure these predictions were speculative, and the mechanism of menthol-dependent TRPM8 gating remained unclear.

We conducted structural studies of full-length TRPM8 from the collared flycatcher Ficedula albicollis (TRPM8FA) using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). TRPM8FA is highly homologous to human and chicken TRPM8 (83% and 94% sequence identity, respectively; fig. S1) which are cold- and menthol-sensitive (14, 20). To prevent proteolysis, we introduced three mutations into TRPM8FA (Phe535Ala, Tyr538Asp, and Tyr539Asp). When expressed in HEK293 cells, both the wild type and the mutant channels exhibited similar menthol-evoked currents and calcium influx, indicating that the mutations do not appreciably affect TRPM8FA function (fig. S2). Notably, the EC50 value and the current-voltage relationship of TRPM8FA for menthol are comparable to those of human and chicken TRPM8 (14, 20).

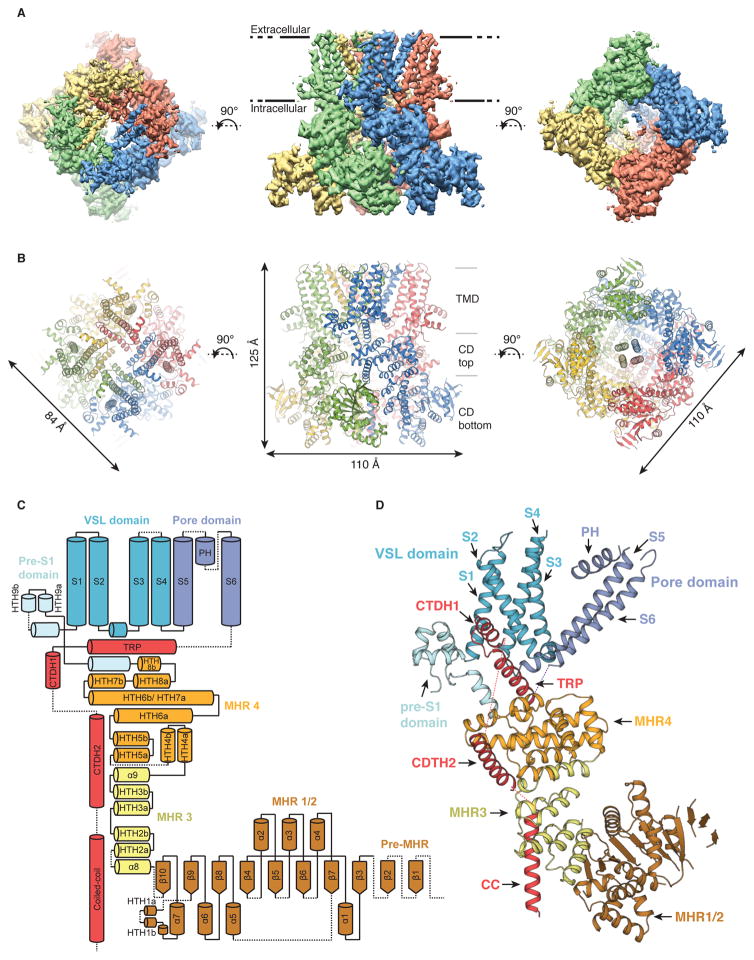

TRPM8FA was frozen in vitreous ice and imaged using a Titan Krios transmission electron microscope with a K2 Summit direct electron detector (See Methods and fig. S3). The final 3D reconstruction was resolved to an overall resolution of ~4.1 Å, with local resolutions ranging from ~3.8 Å at the core to ~8 Å at the periphery (Fig. 1 and fig. S3). The quality of the map allowed for de novo model building (Methods) of 75% of the TRPM8FA polypeptide (fig. S4 and Table S1). The final model for TRPM8FA contains amino acids 122–1100 with multiple loops missing. Several regions (three β-strands in MHRs, C-terminal domain helix 1, and the C-terminal coiled coil) are built as polyalanine (Methods).

Fig. 1. Overall architecture of TRPM8.

(A) Cryo-EM reconstruction and (B) model of TRPM8 viewed from the extracellular side (left), from the membrane plane (middle), and from the cytosolic side (right). (C) Topology diagram delineating the protein domains with secondary structure elements. (D) Detailed view of the atomic model of the TRPM8 protomer.

The TRPM8FA homotetramer is shaped like a three-layered stack of tetragonal bricks with dimensions of approximately 110 Å by 110 Å by 125 Å (Figs. 1A and 1B). The top layer comprises the transmembrane channel domain (TMD) and the lower two layers comprise the cytosolic domain (CD). Each protomer contains a large N-terminal region consisting of MHR1–4, a transmembrane channel region, and a C-terminal region (Figs. 1C and 1D).

The TMs of TRPM8FA assume a fold similar to that of TRPV1/TRPV2, with a voltage-sensor-like domain (VSLD) made up of transmembrane helical segments S1–S4, a pore domain formed by S5 and S6 helices, and one pore helix (23, 24) (Figs. 1 and 2). Similar to previously determined TRPV structures, the TRPM8FA TMD exhibits a domain-swapped arrangement, with the VSLD of one protomer interacting with the pore domain of the neighboring protomer. However, the TMD of TRPM8FA has three features that are distinct from other TRP ion channel architectures. Firstly, relative to the structure of apo TRPV1, the pore helix of TRPM8FA is positioned ~12 Å further away from the central axis, tilted by ~8º, and translated towards the extracellular side by ~5 Å (Figs. 2A and 2B). The putative selectivity filter is poorly resolved in the cryo-EM density map, which prevented accurate model building in this region (fig. S5). Sequence comparison with TRPV1 shows that TRPM8 lacks the turret connecting S5 and the pore helix, instead containing a much longer pore loop (fig. S5). Given the differences in the pore helix position and the sequence surrounding the selectivity filter, we speculate that the TRPM8 selectivity filter adopts an organization that is distinct from TRPV1. The second distinguishing feature of TRPM8FA is the absence of non-α-helical elements (e.g. 310 or π helices) in its TMs, which in other TRP channels were proposed to provide helical bending points important for channel gating (23, 25). In TRPM8FA, a straight α-helical S4 is connected to α-helical S5 via a sharp turn induced by a conserved proline residue (Figs. 2C to 2E). The lack of a bending point in S5 calls to question whether TRPM8FA possesses an S4–S5 linker, which is the structural element critical for vanilloid-dependent TRPV1 gating (26); however, it is possible that a transition from α to π helix in the TRPM8FA S5 may occur during gating, as was suggested for TRPV2 (23). Despite the absence of an obvious S4–S5 linker, TRPM8FA nonetheless forms a domain-swapped tetramer, which is in stark contrast to the calcium-activated K+ channel Slo1, where a similarly short S4–S5 linker prevents formation of a domain-swapped tetramer (27). The overlay of TRPM8FA and TRPV1 protomers reveals that the C-terminal part of TRPM8FA S4 is longer and straight such that it can connect with S5 to achieve a domain-swapped configuration. Furthermore, the sharp turn that connects the α helical S4 and S5 results in a tilt of S5, giving rise to the distinct position of the pore helix as compared to TRPV1 (Figs. 2B and 2C). Thirdly, while TRPV channels have a cytosolic pre-S1 helix, TRPM8FA contains three additional helices between S1 and the cytosolic pre-S1 helix in the putative membrane region: a helix-turn-helix (HTH) followed by an interfacial helix that connects to S1. We term this structural motif, including the cytosolic pre-S1 helix, the “pre-S1 domain”.

Fig. 2. Comparison of the transmembrane domain in TRPM8 and TRPV1.

(A) View down the channel pore from the extracellular side. Dashed red lines indicate the selectivity filter and the pore loop linking the pore helix (PH) and S6 in TRPM8, which were not built in the structure due to the lack of well-resolved cryo-EM density in this region (see Figure S5B). In all panels, the “+” indicates the center of the four-fold symmetry axis. (B) Overlay of the pore domains of TRPM8 (red) and the apo TRPV1 (blue, PDB ID: 3J5P). The pore helix in TRPM8 is located farther away from the ion permeation pathway. (C) Comparison of the junction between S4 and S5. In TRPM8, S5 is straight and fully α-helical, and connected to S4 via a sharp turn, while an S4–S5 linker is identified in TRPV1. The overlay illustrates the differing arrangement of the domain swap between TRPM8 and TRPV1. (D to F) The non-α-helical features in the S4 (D), S5 (E) and S6 (F) of TRPV1 (blue) are absent in those of TRPM8 (red). The differences in tilt of helices originating at helical bending points are indicated with dashed lines. (G to H) Comparison of the pores of the TRPM8 and the apo TRPV1 channels, showing that the S6 gate in TRPM8 is formed by Leu973. (I) The S6 gate of the TRPM8 structure viewed from the intracellular side. Leu973 is shown in sphere representation.

The C-terminal portions of the four α helical S6s are in proximity of each other, providing a constriction point termed the S6 gate (Fig. 2G and fig. S5). The Leu973 residues on each protomer form a tight constriction, with diagonally opposing residues distanced 5.3 Å apart, suggesting that our structure represents a non-conductive conformation (Figs. 2G, 2H and 2I).

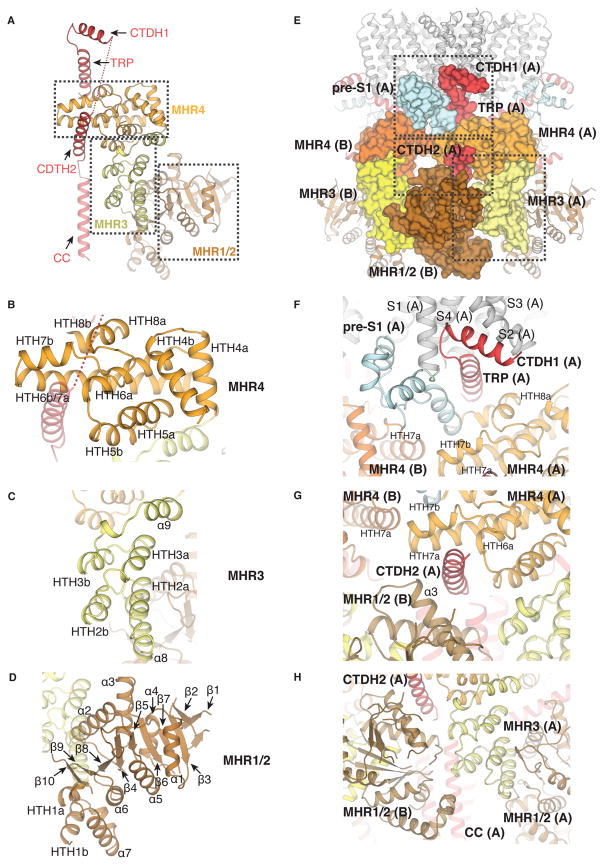

The cytoplasmic domain (CD) is composed of the N-terminal domain (NTD) and the C-terminal domain (CTD) (Fig. 3A). The NTD is composed of four MHRs (MHR1-MHR4). MHR1 and MHR2, along with a part of the pre-MHR region, form a single domain (MHR1/2) with an α/β fold (Fig. 3D). Unlike a typical α/β fold of five β strands surrounded by α helices, MHR1/2 contains a large parallel β sheet composed of about ten β strands sandwiched by about four α helices on each side. The pre-MHR and the tip of MHR1/2 are not well resolved in the reconstruction, precluding model building around this region (Fig. 3 and fig. S4). The MHR3 and 4 are mostly made up of helix-turn-helix (HTH) motifs, but unlike the ankyrin repeats in TRPV channels, the HTHs in MHR3 and MHR4 do not contain hairpin-like protruding loops. The HTHs within MHR3 stack in a sequential fashion, giving rise to the angled position of MHR1/2 relative to MHR4, and resulting in the L-shape of the protomer (Figs. 1D, 3A and 3C). The MHR4 domain, located below the VSLD, consists of five (HTH4-HTH8) non-sequentially stacked HTH motifs (Fig. 3B). The CTD is composed of three helices that are located C-terminal to the TRP domain (Figs. 3A). The first CTD helix (CTDH1) extends from the TRP domain. It then connects to the second CTD helix (CTDH2) via a long loop, which is positioned below HTH6 and HTH7 of MHR4, and runs almost parallel with the TRP domain (Figs. 3A and 3B). The C-terminal region of the CTDH2 points toward the cytoplasmic cavity and connects to a tetrameric coiled coil (CC) at the central axis (Figs. 3A and 3B). The limited resolution of the cryo-EM density around the CC prevents accurate modeling of this region, but the relatively short (~25 amino acids) and parallel architecture of the TRPM8FA CC contrasts the long (>50 amino acids), anti-parallel architecture observed in the CC fragment structure of TRPM7 (28).

Fig. 3. The cytoplasmic domain of TRPM8.

(A) The organization of the N- and C-terminal regions of the channel within the cytoplasmic domain (CD). (B to D) Close-up views of MHR4 (B), MHR3 (C), and the single domain MHR1/2 (D) that comprise the N-terminal domain. (E) Surface representation of the interactions between different domains from the neighboring subunits (A) and (B). (F to H) Close-up views of the domain interfaces that contribute to communication between the TMD and CTD (F), between the top and bottom layers of the cytoplasmic ring (G), and between protomers in the bottom layer of the cytoplasmic ring (H).

In contrast with TRPV1, TRPM8FA makes extensive intra- and inter-subunit interactions (Figs. 3E). First, while the interaction between the TMD and CD is primarily mediated by the interfacial TRP domain in TRPV1, in TRPM8FA the pre-S1 domain establishes additional TMD-CD interactions through contacts with the tip of HTH7b in MHR4 from the adjacent subunit (Figs. 3F and fig. S6B). Second, the CTDH2 runs parallel to the TRP domain, but is translated ~29 Å toward the cytosolic side (Fig. 3G), positioned beneath MHR4 and contacting the MHR1/2 of the adjacent subunit (Fig. 3G and figs. S6C and S6D). The CTDH2 is therefore in contact with both the top and the bottom layers of the cytoplasmic ring. Based on its position at this inter-layer and inter-subunit nexus, the CTDH2 might have a role in channel gating as well as cytoplasmic ring assembly. Third, in the bottom layer of the cytoplasmic ring, the tips of two HTH motifs (HTH2a and HTH2b) from MHR3 and the loop of MHR1/2 from the neighboring protomer establish an inter-subunit network of interactions (Figs. 3H and fig. S6D). These extensive interfacial interactions are the distinguishing features of TRPM8, which may be important for either cold- or menthol-dependent channel gating.

Unlike TRPV channels, TRPM8 contains arginine residues in S4 of the VSLD (Fig. 4A). Arg842 in S4 and Lys856 in S5 (Arg841 and Lys855 in TRPM8FA, respectively), contribute to the voltage-dependence in human TRPM8 (13). In TRPM8FA, many aromatic and aliphatic residues within the VSLD form a large hydrophobic “seal” (Fig. 4A) between the extracellular side and the middle of the membrane. Between this hydrophobic seal and the TRP domain, there is a large cavity we term the VSLD cavity, which is also present in TRPV channels (23, 26). In the TRPM8FA structure, Arg841 points toward the center of the VSLD cavity, where three acidic residues form a negatively charged cluster. Although we are unable to unambiguously assign the interaction pairs between the charged residues, this arrangement is more reminiscent of a canonical voltage sensor than the VSLD of TRPV1 (Fig. 4A) (24, 29). We also observed that Lys855 is located at the beginning of S5 outside the VSLD, but it is unclear how this residue contributes to voltage sensing. Despite the similarities in the positions of charged residues in the TRPM8FA VSLD and the canonical voltage sensor, we postulate that the degree and the type of voltage-sensing motion in TRPM8 is different from canonical voltage-gated ion channels due to the large size of the hydrophobic seal and the fact that a small gating charge (~1 eo) is associated with voltage gating of TRPM8 (13).

Fig. 4. The voltage-sensor like domain (VSLD) and the putative menthol binding site in the VSLD cavity.

(A) Comparison of the VSLD in TRPM8 (marine) with the canonical voltage-sensor domain in the Kvchim channel (green) (PDB ID: 2R9R) and the VSLD of TRPV1 (purple) (PDB ID: 3J5P). A gating charge Arg841 in the VSLD of TRPM8 is near three negatively charged amino acids below a large hydrophobic seal (spheres in bright orange) in TRPM8 (left). Many gating charge arginines in S4 of Kvchim are located above and below a small hydrophobic seal (spheres in bright orange) and interact with negatively charged amino acids (middle). The interior of the VSLD of TRPV1 is lined with hydrophobic and polar amino acids. (B) Residues critical for the sensitivity of TPRM8 to menthol (shown in green stick representation) were mapped to S1 (Tyr745), S4 (Arg841), and the TRP domain (Tyr1004). Residues implicated in icilin sensitivity of TRPM8 (yellow stick representation) were mapped to S3 (Asn799 and Asp802). All of these residues point toward the VSLD cavity.

Many studies have been conducted to elucidate the mechanism of TRPM8 activation by ligand binding. It has been reported that Arg842 (Arg841 in TRPM8FA) also affects menthol- and cold-dependent activation of human TRPM8. Based on [3H]menthol binding studies, this residue appears to interact with menthol (13). Residues Tyr745 and Tyr1005 (Tyr1004 in TRPM8FA) were shown to be involved in menthol binding, but not cold sensing (19). Tyr745 was also found to be critical for binding of the inhibitor SKF96365 (21), further indicating that this residue is central to ligand-dependent gating in TRPM8. In addition, studies have identified Asn799, Asp802, and Gly805 as important for icilin binding (20). It was predicted that these ligand-binding sites were all located at the membrane-facing region of S2–S3 (20–22). We can now place these functional studies in the proper structural context. Notably, residue Tyr745 is located at the middle of S1, directed towards the center of the VSLD cavity (Fig. 5B). This contrasts with its previously predicted location in the membrane-facing side of S2. Furthermore, all residues implicated in menthol binding (Tyr745, Arg841, and Tyr1004) are located in the VSLD cavity (Fig. 4B). We propose that the VSLD cavity is the binding site for menthol and menthol-like molecules in TRPM8. Interestingly, the corresponding cavity in TRPV channels has been implicated in lipid binding (23, 26) and modulation of channel gating (23). We propose that menthol binding in the VSLD cavity in TRPM8 might modulate the S6 gate through interactions with the TRP domain.

PIP2 is necessary for TRPM8 activation, as depletion of PIP2 has been shown to desensitize the channel (11–13). Furthermore, recent studies have suggested that PIP2 alone can activate TRPM8 (11–13). Mutagenesis studies identified Lys995, Arg998, and Arg1008 (Lys994, Arg997, and Arg1007 in TRPM8FA) as important for PIP2-dependent channel gating (11). All of these residues are located in the TRP domain: Arg1007 is located on the side of the TRP domain facing the VSLD cavity, and Lys994 and Arg997 are located on the side of the TRP domain facing the pre-S1 domain and HTH6 in MHR4 from the neighboring subunit (fig. S7). Our structure suggests that the VSLD cavity is unlikely to bind PIP2, since the net charge of its interior is negative and this cavity is not large enough to accommodate both menthol and PIP2. The reported effects of mutations to Arg1008 may reflect downstream conformational changes following PIP2 binding. Notably, we found that the interface between the TRP domain, the pre-S1 domain, and MHR4 contains many basic amino acid residues, including the previously identified Lys994 and Arg997 (fig. S7). We speculate that PIP2 binds at this interfacial site, where it could modulate the position of the TRP domain to enable a non-desensitized state. The distinct location of this putative PIP2 binding site compared to TRPV1 and TRPML reflects the diverse effects of PIP2 on TRP channels (25, 26).

In the context of previous mutagenesis data, our structural analyses suggest that the ligand-dependent gating mechanism of TRPM8 differs substantially from TRPV1. In TRPV1, the binding of vanilloid to the S4b and the S4–S5 linker is thought to induce a “swivel” motion in the TRP domain, which would pull on S6 to open the S6 gate (23, 30). We suggest that menthol binds in the VSLD cavity, which is distinct from the vanilloid binding site in TRPV1. Whereas vanilloid-mediated gating involves non-α-helical elements (310 and π helices) and an S4–S5 linker, neither of these structural features appear to be present in the conformational state of our TRPM8FA structure. Thus, we speculate that ligand-induced repositioning of the TRP domain in TRPM8 may directly lead to the opening of the S6 gate.

Our observation of the extensive inter-subunit interactions between the TMD and the top layer of the CD ring leads us to speculate that the gating-related TRP domain motion may also involve the top layer of the CD ring (Fig. 3F and fig. S6B). Furthermore, the CTDH2, with its central position within the CD and its link with the TRP domain, may be important for coupling the movements of the TRP domain to those of the MHR elements and especially MHR4 (Fig. 3G and fig. S6D). In addition, the tetrameric coiled coil located in the bottom layer ring may play a role in regulating the position of CTDH2.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Sequence alignment of TRPM8 orthologs

Fig. S2. Functional characterization of the TRPM8 channel.

Fig. S3. Cryo-EM data collection.

Fig. S4. Quality of electron density of key elements in the structure

Fig. S5. The pore domain of TRPM8FA differs from that of TRPV1.

Fig. S6. Domain interfaces and channel assembly.

Fig. S7. A putative binding pocket for PIP2.

Table S1. Data collection, reconstruction, and model refinement statistics.

Acknowledgments

Cryo-EM data were collected at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) electron microscopy facility. We thank Yang Zhang and Huanghe Yang at Duke University who provided access to their calcium imaging apparatus and guidance to calcium imaging experiments. We thank Jean-Christophe Ducom at TSRI High Performance Computing facility for computational support, Bill Anderson for microscope support, and Mark Herzik and Saikat Chowdhury for helpful discussion and training. We thank Zach Johnson for advice on sample freezing. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R35NS097241 to S.-Y. L., DP2EB020402 to G.C.L.). G.C.L is supported as a Searle Scholar and a Pew Scholar. Computational analyses of EM data were performed using shared instrumentation funded by NIH S10OD021634. The coordinates are deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the PDB ID 6BPQ and the electron density maps have been deposited in EMDB with the ID EMD-7127.

References and Notes

- 1.Fleig A, Penner R. The TRPM ion channel subfamily: molecular, biophysical and functional features. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farooqi AA, et al. TRPM channels: same ballpark, different players, and different rules in immunogenetics. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:773–787. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKemy DD, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature. 2002;416:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peier AM, et al. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108:705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bautista DM, et al. The menthol receptor TRPM8 is the principal detector of environmental cold. Nature. 2007;448:204–208. doi: 10.1038/nature05910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhaka A, et al. TRPM8 is required for cold sensation in mice. Neuron. 2007;54:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colburn RW, et al. Attenuated cold sensitivity in TRPM8 null mice. Neuron. 2007;54:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu B, et al. TRPM8 is the principal mediator of menthol-induced analgesia of acute and inflammatory pain. Pain. 2013;154:2169–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews MD, et al. Discovery of a Selective TRPM8 Antagonist with Clinical Efficacy in Cold-Related Pain. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:419–424. doi: 10.1021/ml500479v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weyer AD, Lehto SG. Development of TRPM8 Antagonists to Treat Chronic Pain and Migraine. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2017;10 doi: 10.3390/ph10020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Michailidis I, Logothetis DE. PI(4,5)P2 regulates the activation and desensitization of TRPM8 channels through the TRP domain. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:626–634. doi: 10.1038/nn1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu B, Qin F. Functional control of cold- and menthol-sensitive TRPM8 ion channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1674–1681. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3632-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voets T, Owsianik G, Janssens A, Talavera K, Nilius B. TRPM8 voltage sensor mutants reveal a mechanism for integrating thermal and chemical stimuli. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:174–182. doi: 10.1038/nchembio862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voets T, et al. The principle of temperature-dependent gating in cold- and heat-sensitive TRP channels. Nature. 2004;430:748–754. doi: 10.1038/nature02732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baez D, Raddatz N, Ferreira G, Gonzalez C, Latorre R. Gating of thermally activated channels. Curr Top Membr. 2014;74:51–87. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800181-3.00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clapham DE, Miller C. A thermodynamic framework for understanding temperature sensing by transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:19492–19497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117485108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phelps CB, Gaudet R. The role of the N terminus and transmembrane domain of TRPM8 in channel localization and tetramerization. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:36474–36480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuruda PR, Julius D, Minor DL., Jr Coiled coils direct assembly of a cold-activated TRP channel. Neuron. 2006;51:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandell M, et al. High-throughput random mutagenesis screen reveals TRPM8 residues specifically required for activation by menthol. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:493–500. doi: 10.1038/nn1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuang HH, Neuhausser WM, Julius D. The super-cooling agent icilin reveals a mechanism of coincidence detection by a temperature-sensitive TRP channel. Neuron. 2004;43:859–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malkia A, Pertusa M, Fernandez-Ballester G, Ferrer-Montiel A, Viana F. Differential role of the menthol-binding residue Y745 in the antagonism of thermally gated TRPM8 channels. Mol Pain. 2009;5:62. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedretti A, Marconi C, Bettinelli I, Vistoli G. Comparative modeling of the quaternary structure for the human TRPM8 channel and analysis of its binding features. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zubcevic L, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the TRPV2 ion channel. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao M, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. Structure of the TRPV1 ion channel determined by electron cryo-microscopy. Nature. 2013;504:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirschi M, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the lysosomal calcium-permeable channel TRPML3. Nature. 2017;550:411–414. doi: 10.1038/nature24055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao Y, Cao E, Julius D, Cheng Y. TRPV1 structures in nanodiscs reveal mechanisms of ligand and lipid action. Nature. 2016;534:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature17964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao X, Hite RK, MacKinnon R. Cryo-EM structure of the open high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature. 2017;541:46–51. doi: 10.1038/nature20608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujiwara Y, Minor DL., Jr X-ray crystal structure of a TRPM assembly domain reveals an antiparallel four-stranded coiled-coil. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:854–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long SB, Tao X, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao E, Liao M, Cheng Y, Julius D. TRPV1 structures in distinct conformations reveal activation mechanisms. Nature. 2013;504:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goehring A, et al. Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:2574–2585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zakharian E, Thyagarajan B, French RJ, Pavlov E, Rohacs T. Inorganic polyphosphate modulates TRPM8 channels. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubochet J, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy of vitrified specimens. Q Rev Biophys. 1988;21:129–228. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suloway C, et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J Struct Biol. 2005;151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lander GC, et al. Appion: an integrated, database-driven pipeline to facilitate EM image processing. J Struct Biol. 2009;166:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voss NR, Yoshioka CK, Radermacher M, Potter CS, Carragher B. DoG Picker and TiltPicker: software tools to facilitate particle selection in single particle electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2009;166:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogura T, Iwasaki K, Sato C. Topology representing network enables highly accurate classification of protein images taken by cryo electron-microscope without masking. J Struct Biol. 2003;143:185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roseman AM. FindEM--a fast, efficient program for automatic selection of particles from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol. 2004;145:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SH, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen S, et al. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2013;135:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holm L, Laakso LM. Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W351–355. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin P, et al. Electron cryo-microscopy structure of the mechanotransduction channel NOMPC. Nature. 2017;547:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature22981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta crystallographica Section D, Biological crystallography. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heymann JB, Belnap DM. Bsoft: image processing and molecular modeling for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nilius B, et al. The selectivity filter of the cation channel TRPM4. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:22899–22906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501686200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Sequence alignment of TRPM8 orthologs

Fig. S2. Functional characterization of the TRPM8 channel.

Fig. S3. Cryo-EM data collection.

Fig. S4. Quality of electron density of key elements in the structure

Fig. S5. The pore domain of TRPM8FA differs from that of TRPV1.

Fig. S6. Domain interfaces and channel assembly.

Fig. S7. A putative binding pocket for PIP2.

Table S1. Data collection, reconstruction, and model refinement statistics.