Child abuse is unfortunately prevalent worldwide. It includes a plethora of physical, sexual, psychological, and economic violation or maltreatment targeted at an individual <18 years of age. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines child abuse and child maltreatment as “all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power.” Child sexual abuse (CSA) is defined by the WHO as “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend and is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared, or else that violate the laws or social taboos of society.”[1] In many developing countries, including India, there is a lack of awareness and understanding about the prevalence and adverse repercussions of the crisis. Globalization and economic liberalization with the resultant socioeconomic transformation and a major trend to urbanization in India have contributed to the increased vulnerability of children and adolescents to different and novel forms of abuse. The term “Child Abuse” may have different meanings in different cultural environments and socioeconomic situations. Above all, a universal definition of child abuse in the Indian settings has not yet been defined.

The dynamics of CSA differ from those of adult sexual abuse. Children rarely disclose sexual abuse immediately after the event. Moreover, the disclosure tends to be a process rather than a single episode and is often initiated following a physical complaint or a change in behavior. The mental and physical trauma faced by the survivor of CSA is unimaginable, especially in a society where blaming the victim is the norm. Despite this, CSA is an issue which is neither addressed nor discussed, but is avoided, neglected, or brushed under the carpet. This is obvious from the fact that until recently people could not be punished for reprehensible behavior toward children including sexual abuse (not amounting to intercourse), mental harassment, and even being used for pornography had no laws against them. To remedy the situation, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences 2012 act was promulgated. The law has made a difference; there is increased awareness and there is a rapid increase in the number of cases registered under the act.[2] Unfortunately, despite the new law, the situation on the ground remains more or less unchanged.

Although poverty is strongly associated with CSA, it is equally prevalent in affluent societies across a wide range of religious and cultural backgrounds. In India, there is a trend away from joint to nuclear families, with both parents holding jobs to accommodate the ever-increasing financial demands. As a result, more often than not, young children are usually left to take care of themselves or have to be left in care of crèches. This makes the kids even more vulnerable to being abused. In rural and semi-urban India where child labor is still a predominant hazard in society, children are physically as well as sexually put to a test.

The global figures of prevalence of CSA are mind-boggling. In 2002, the WHO estimated that worldwide 150 million females and 73 million males under the age of 18 years suffered CSA.[3] A meta-analysis of 65 studies from 22 nations revealed that CSA occurred in 19.7% of girls and 7.9% of boys. The prevalence of CSA in Africa, Asia, America, and Europe was 34.4%, 23.9%, 10.1%, and 9.2%, respectively. South Africa had the highest prevalence of CSA for both men (60.9%) and women (43.7%). For men, the second highest prevalence of CSA was found in Jordan (27%), followed by Tanzania (25%), Israel (15.7%), Spain (13.4%), Australia (13%), and Costa Rica (12.8%). The prevalence rates of CSA for men in the remaining countries were <10%. For women, the second highest prevalence of CSA was seen in Australia (37.8%), followed by Costa Rica (32.2%), Tanzania (31.0%), Israel (30.7%), Sweden (28.1%), the United States (25.3%), and Switzerland (24.2%). The authors also mentioned that the lower rate for males may not reflect the reality; there may be underreporting of male CSA due to intense shame and fear of being labeled a sissy (if the perpetrator was a female) or homosexual (if the perpetrator was male) or weak.[4]

Indian children, at 440 million, constitute 19% of the world's population of children. India also has the dubious distinction of having the largest number of CSA cases in the world.[5] While the actual figures of CSA in India are not known, a few well-planned studies have been conducted. In 1998, the first survey of CSA in India reported a prevalence of 76%.[6] On the other hand, an United Nations International Children Education Fund study during 2005–2013 reported that CSA in Indian girls was 42%.[7] In 2007, a major state-sponsored survey in India reported the prevalence of CSA as 53%. A major finding of the study was that “persons known to the child or in a position of trust and responsibility” were the perpetrators of CSA in half of the cases. Widespread abuse was prevalent in almost all states. An analysis of different evidence groups revealed that the highest percentage of children who faced sexual abuse were those at work (61.61%), followed by on streets (54.51%), in family environment (53.18%), in schools (49.92%), and in institutional care (47.08%). Assam (57.27%) followed by Delhi (41%), Andhra Pradesh (33.87%), and Bihar (33.27%) had the highest prevalence of severe sexual abuse.[8]

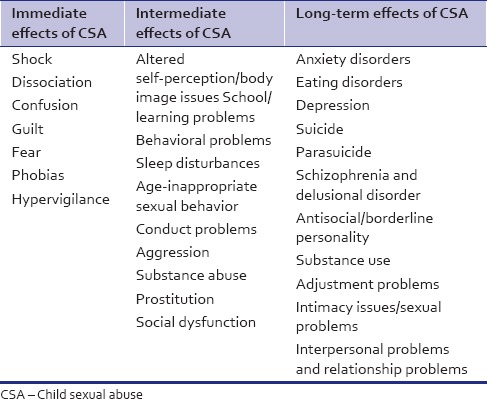

The ripple effects of CSA can be difficult to pinpoint, even though abuse may affect every area of an individual's life. These effects might not necessarily be permanent but can be overwhelming. Childhood mental disorders are significantly more common in children with sexual abuse and the risk is higher in boys than girls. CSA can damage the child's self-concept, sense of trust, and perception of the world as a relatively safe place, irrespective of gender. Substantial research has revealed that children who have undergone CSA face a wide variety of emotional and behavioral problems.[9] Significantly higher prevalence of anxiety disorders, personality disorders, organic disorders, childhood mental disorders, and conduct disorders was observed in male survivors of CSA. On the other hand, significantly higher prevalence of major affective disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, organic disorders, childhood mental disorders, and conduct disorders was seen in female survivors of CSA.[10] A study carried out on prospective data from 831 children and parents participating in the Longitudinal Studies on Child Abuse and Neglect found a risk of more intimidation and physical assault in subsequent peer relationships; however, no gender differences were noted to be present.[11] History of CSA was also found to be associated with high-risk sexual behavior among adolescents, of which unprotected sexual intercourse was the most common.[12] Consequences of CSA are summarized in Table 1.[13,14]

Table 1.

Consequences of child sexual abuse

Among the psychiatric disorders in childhood, a close association of conduct disorder with CSA has been reported. In preadolescent children, sexual abuse often leads to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention deficit, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and phobic and conduct disorders. In adolescent children, the experience of CSA has a strong association with feelings of hopelessness, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempt.[15]

CSA, especially involving rape prior to 16 years of age, is strongly associated with psychosis.[16] A longitudinal cohort study of more than 1000 children from New Zealand revealed that the prevalence of substance use disorder, major depression, anxiety disorder, conduct disorder, and suicidal behaviors was significantly higher among those who reported CSA when compared with those who did not report CSA. There was a positive relationship between the risk of disorder and extent of CSA, with the highest risk of disorder in those had suffered forcible intercourse during abuse.[12] A systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 longitudinal, epidemiological studies with 3,162,318 participants found a significant association between sexual abuse and anxiety disorder, depression, eating disorders, PTSD, sleep disorders, and suicidal attempts but not with schizophrenia or somatoform disorders.[17]

Children very often do not disclose their horrible “secret” and suffer in silence. However, CSA usually causes strong emotions including fear, confusion, shame, guilt, anger, betrayal, helplessness, depression, and despair. Survivors of CSA may consider themselves as different, dirty, and damaged. Due to various emotional, social, and cultural reasons, survivors of CSA may not be able to articulate their experiences and feelings. A major reason for this is that the children are traumatized and are unaware of the suitable words to communicate their experience. CSA has long-lasting adverse effects on mental health. Effects may be immediate, intermediate, and long term.

It is imperative to appreciate that means should be available to provide therapy to enable survivors to heal, the absence of which may adversely affect their sexuality, behavior, and emotions for life.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health organization, Child Sexual abuse; 2003. [Last accessed on 25 Oct 2016]. Child sexual abuse. Guidelines for medicolegal care for victims of sexual violence. Available from: Whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/924154628x.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belur J, Singh BB. Child sexual abuse and the law in India: A commentary. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 25];Crime Sci. 2015 4:26. DOI 10.1186/s40163-015-0037-2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Child maltreatment. updated 2014. Geneva: World Health organization; [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 25]. Child Maltreatment. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/child_abuse/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:328–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh MM, Parsekar SS, Nair SN. An epidemiological overview of child sexual abuse. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3:430–5. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breaking the Silence. Child Sexual Abuse in India. USA: Humans Rights Watch; 2013. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/india0113ForUploadpdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray A 42% of Indian Girls are Sexually Abused before 19: Unicef. The Times of India; 12 September, 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/42.of.Indian.girls.are.sexually.abused.before.19.Unicef/articleshow/42306348.cms?

- 8.Kacker L, Mohsin N, Dixit A. Study on Child Abuse: India 2007. New Delhi: Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spataro J, Mullen PE, Burgess PM, Wells DL, Moss SA. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health: Prospective study in males and females. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:416–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mullers ES, Dowling M. Mental health consequences of child sexual abuse. Br J Nurs. 2008;17:1428–30. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2008.17.22.31871. 1432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benedini KM, Fagan AA, Gibson CL. The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;59:111–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogolyubova O, Skochilov R, Smykalo L. Childhood victimization and HIV risk behaviors among university students in Saint-Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Care. 2016;28:1590–4. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1191604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gold J, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. The relation between abuse and violent delinquency: The conversion of shame to blame in juvenile offenders. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:459–67. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putnam FW. Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:269–78. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, King M, Cooper C, Brugha T, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: Data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199:29–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1365–74. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:618–29. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]