Abstract

Background:

Tobacco use is an important preventable health risk factor in India.

Aim:

This study was carried out to estimate the prevalence of current tobacco use, factors and extent of dependence associated with its use among male workers of an industrial organization.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 759 participants randomly selected from the population of employees were administered questionnaire in Hindi containing demographic profile, patterns of smoking, and use of smokeless tobacco and alcohol.

Results:

Forty-one percent of the surveyed males (n = 750) used tobacco either by smoking or smokeless method or both (9.7% used both, 23.4% smoked, and 27.3% used smokeless tobacco). The maximum percentage was among the 26–30 years’ age group, and the married persons (45.4%, OR = 2.17, P < 0.05). Tobacco use was associated with lower educational qualifications, history of tobacco use in family members, and drinking alcohol. Seventy-two percent of the nicotine users reported being influenced by their peers in initiating the habit, 59.4% of the users reported being advised to stop tobacco use by a health professional, and 52.9% had attempted quitting the habit more than once. Twenty percent of our sample were dependent on nicotine and the highest prevalence was seen in those using both smoking and the smokeless tobacco.

Conclusions:

The Prevalence of Tobacco Use and Nicotine Dependence among male industrial employees is significant and necessitates Tobacco awareness and cessation programs regarding Tobacco use.

Keywords: Nicotine, nicotine dependence, tobacco use

The number of cigarettes smoked around the world in the year 2014 was estimated to be around 5.8 trillion and around 300 million people used smokeless tobacco. The vast majority of these were in South east Asia.[1] Despite numerous Health awareness campaigns, pictorial warnings on tobacco products, smoke free policies and the legislative measures adopted by the Government of India, the number of tobacco users are substantial in numbers. The numbers of men smoking any type of tobacco at ages 15–69 years rose from 7.9 crores in 1998 to 10.8 crores in 2015.[2]

Tobacco use is an important preventable public health issues of the world and projected to be the single largest cause of mortality world wide. India has one of the largest number of People with Oral Cancer attributable to Tobacco Use. The tobacco smoke can interact with other occupational or non occupational carcinogens and increase the risk of developing lung cancer.[1] Tobacco use has an adverse impact on the health of an organization too. Cigarette smokers are reported to have higher rates of absenteeism, impaired perceptual and motor skills and poorer endurance than non smokers.[3]

Tobacco use is a complex multistage behaviour influenced by the genes and the environment.[4] The active content of tobacco ‘Nicotine’ leads to physical and psychological dependence comparable to the dependence on Heroin. Tobacco users have to overcome the nicotine dependence before they are successful in quitting tobacco usually leads to experimentation with other drugs of abuse too.

A few studies have been done in various categories of industrial workers in India with varying prevalence rates. M Parashar et al reported prevalence of smokeless tobacco user of 49%, smokers 22% and dual users 22% in a study in a sample of 172 male construction workers in Delhi. More than half of them were moderate to severely dependent on Nicotine.[5] Shoeeb Akram et al reported prevalence of tobacco use among 134 wood and plywood workers in Mangalore to be around 53.7% of which 11.9% were smokers and 41.5% tobacco chewers.[6] Ansari et al surveyed a sample of 448 power loom workers of Allahabad (UP) and found a prevalence of smoking 62.28% and tobacco chewing of around 66.07%.[7] A telephonic survey of 646 BPO industry employees revealed 415 were current tobacco users and prevalence of 49.5% in the male employees. 10% of the smokers and 16 % of the smokeless tobacco users had Fagerstrom scores more than 5.[8]

A few studies have been done in various categories of industrial workers in India with varying prevalence rates. M Parashar et al reported prevalence of smokeless tobacco user of 49%, smokers 22% and dual users 22% in a study in a sample of 172 male construction workers in Delhi. More than half of them were moderate to severely dependent on Nicotine.[5] Shoeeb Akram et al reported prevalence of tobacco use among 134 wood and plywood workers in Mangalore to be around 53.7% of which 11.9% were smokers and 41.5% tobacco chewers.[6] Ansari et al surveyed a sample of 448 power loom workers of Allahabad (UP) and found a prevalence of smoking 62.28% and tobacco chewing of around 66.07%.[7] A telephonic survey of 646 BPO industry employees revealed 415 were current tobacco users and prevalence of 49.5% in the male employees. 10% of the smokers and 16 % of the smokeless tobacco users had Fagerstrom scores more than 5.[8]

It was felt that a survey of larger sample of Industrial workers is required to estimate the burden of tobacco use in industrial workers of this country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A population-based, cross-sectional survey was conducted using a self-administered questionnaire on males in an industrial setup located in western region of India. We assumed a 0.40 prevalence of tobacco use (p) and 0.60 prevalence of nonuse (q) with a degree of precision (d) of 0.04 at 95% confidence interval (CI). The sample size was calculated by the following equation: ([Z2 × p × q]/[d2]). The minimum sample size estimated was 576. All the personnel on the strength were approached and participants were selected using simple random sampling. The authors administered the questionnaire written in Hindi which covered demographic profile, patterns and determinants of smoking, smokeless tobacco, and alcohol. Nicotine dependence was assessed by the scores on Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)[9]. A Hindi-translated version of FTND with modifications to assess the smokeless tobacco use was used. The translated version of the questionnaire was back translated before use. The nicotine-dependent individuals were identified by their FTND score if it was ≥5.

A lecture on the ill effects of tobacco use in Hindi was conducted after collection of the filled questionnaires.

Data were collated and analyzed using Epi Info. Point estimates and patterns of current tobacco use were determined. Current tobacco use included both daily and nondaily or occasional use. Statistical associations between tobacco use status, dependence, and study variables were tested with Chi-squared distribution with the level of significance set at P < 0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CI were computed.

RESULTS

Out of the 759 questionnaires administered, nine were rejected due to incomplete/blank submissions. Age of the participants ranged from 18 to 54 years. The mean age in our sample was 32.7 years (standard deviation: 8.12 years). Range of years of service in the organization was 1–31 years. The mean duration of service in the industry was 13.7 years (standard deviation: 7.8). Nearly 95.1% of the employees were classified as healthy in their annual health inspection.

The overall prevalence of current tobacco use in the study population was 41% (41% ± 3.5%, 95% CI); smokers were 23% and smokeless tobacco users were 28%. Breakdown of tobacco use was 9.7% smoked as well as used smokeless tobacco, 17.6% used only smokeless tobacco, and 13.7% were exclusive tobacco smokers.

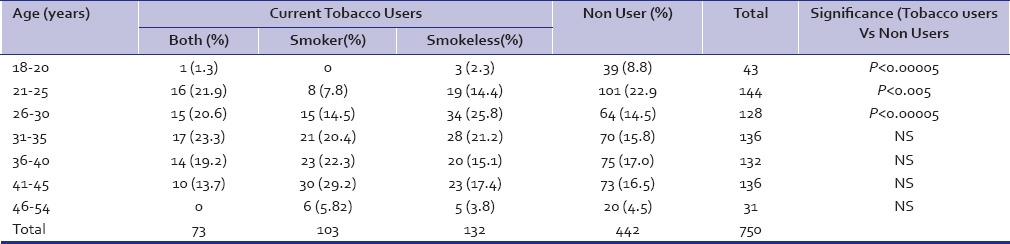

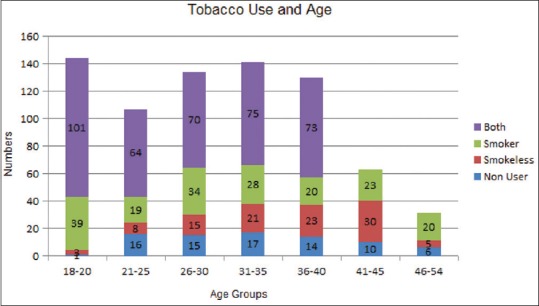

Details of the tobacco use by age and duration of service are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Figure 1 shows distribution of tobacco users by age. Fifty percent of the 26–30 years’ age group were found to use tobacco (OR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.04 < OR < 2.31, P < 0.05). Oral tobacco use was also found to be highest in this age group.

Table 1.

Distribution of Industrial Workers by age

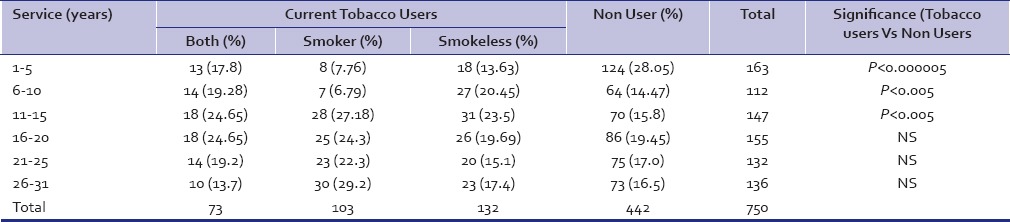

Table 2.

Distribution of Industrial Workers by years of service

Figure 1.

Distribution of Tobacco Users in Industrial Workers by Age

The percentage of tobacco users was the highest (25%) in the industrial workers with 11–15 years of service in the organization (OR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.21 < OR < 2.59, P < 0.005). Users of smokeless tobacco, smokers, and users of “both” were also highest in this group as compared to others. Among the exclusive smokers, being the highest, 29% were in the 41–45 years’ age group.

Among the smokers, the predominant types of tobacco used were cigarettes (57.3%), bidi (32.2%), and both (8.8%). Three persons reported hukka use. We found the use of smokeless tobacco to be higher as compared to smoking in lower age groups.

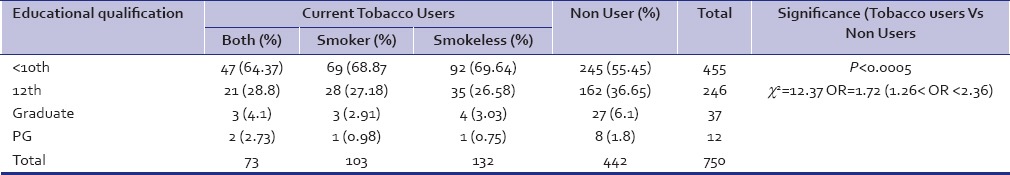

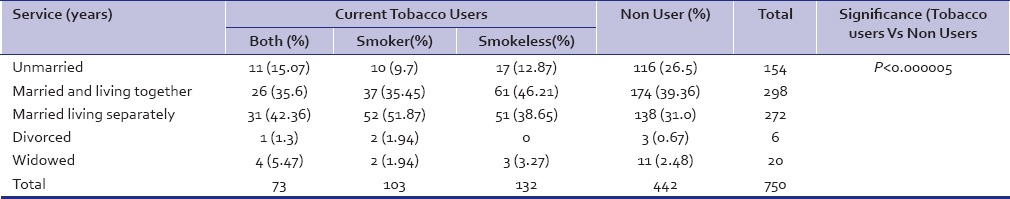

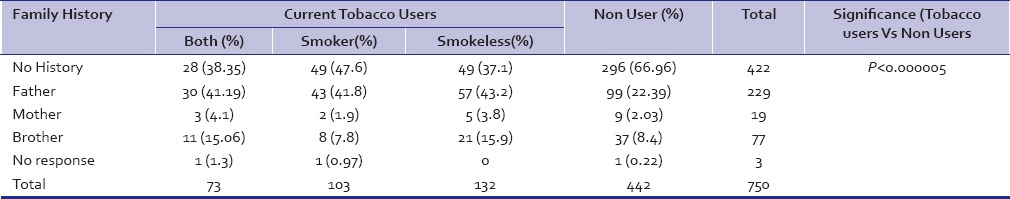

Use of tobacco was higher (45%) among persons with lower educational qualifications [Table 3]. Sixty-eight percent of tobacco users had an educational qualification up to class X (OR = 1.72, 95% CI 1.26 < OR < 2.361, P < 0.0005). Among tobacco users, married persons constituted the largest group as compared to unmarried, divorced, and widower (OR = 2.17, 95% CI 1.48 < OR < 3.17, P < 0.00005) [Table 4]. History of tobacco use in a family member [Table 5] was found to be a significant risk factor for tobacco use. Tobacco use by father (OR = 3.08, 95% CI 2.18 < OR < 4.37, P < 0.000005) and the brother (OR = 2.54, 95% CI 1.51 < OR < 4.28, P < 0.0005) was significant.

Table 3.

Distribution of Industrial Workers by Educational qualifications

Table 4.

Distribution of Industrial Workers by Marital details

Table 5.

Distribution of Industrial Workers by Family History

Nearly 72% of the tobacco users reported peer group influence in initiating tobacco use. Other influences were family (2.9%) and advertisements (8.4%). About 52.9% reported being advised to quit tobacco by a health professional. Nearly 57.1% of tobacco users reported concomitant alcohol use (OR = 4.95, 95% CI 3.53 < OR < 6.96, P < 0.0000005).

The mean scores on FTND for smokers and smokeless tobacco users were 2.85 ± 2.4 and 2.58 ± 2.3, respectively. Overall prevalence of nicotine dependence in our sample was 20%. Thirty-four percent of the users of both smokeless tobacco and smoking were highly dependent on nicotine compared to 17% of only smokeless tobacco users and 18% of exclusive smokers. The highest prevalence of nicotine dependence was in the 31–35 years’ age group among smokers (OR = 3.45, P < 0.05), 36–40 years’ age group among smokeless tobacco users (OR = 6.23, P < 0.001), and 26–30 years’ age group in those using smokeless and smoking routes of tobacco use (OR = 3.94, P < 0.05). The ORs for nicotine dependence were significant at 16–20 years of smoking (OR = 3.45, P < 0.05) versus 6–10 years of smokeless tobacco use (OR = 9.00, P < 0.05).

Nicotine dependence scores in FTND were significant among the married persons living separately from their families. History of tobacco use in the family and concomitant alcohol use were also significantly related to nicotine dependence.

DISCUSSION

The overall prevalence of tobacco use in our study sample (41%) is comparable to the data of National Family Health Survey 4 (2014-15) which had reported men who use any kind of tobacco in urban area to be 39.2 %. Our figures were lesser when compared to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS) done in 2009-10 (47.9%).[10,11] This could be due to the selective representation in our sample. However the prevalence of smokeless tobacco users were comparable in our sample (28%) with GATS India (32.9%). The prevalence of smokers were 23% in our sample was also comparable to that of the GATS India survey figure of 24.3%. The prevalence of smokeless tobacco use in our sample was lesser when compared to the figures reported in the other indian studies on industrial employees.[5,6,7]

Percentage of Current Tobacco use in our sample increased till the age group of 26-30 years and then plateaued unlike the GATS India where the upward trend continued till the 45-65 years age group in males.[11] Analysis by Chi Square for trend by the Mantel Extension method for smokers by age showed increasing trend (Chi Square 22.4, p < 0.00000) compared to the baseline age group of 18-25 years. This also implies a rising trend in the number of smokers with the increasing age.

The prevalence of parental smoking was found to be 42.2% in tobacco users. 74.4% smokers reported being influenced by peers for their initiation into tobacco use. The findings with regard to tobacco use, and its relation to educational qualification and concomitant alcohol alcohol use were no different from other studies.

Nicotine dependence is one of the difficult addictions to be cured of. The quantification of nicotine delivered inside the body is not the same with the various tobacco products available in India and is a limitation of the assessment methodology available to us. The Nicotine content in a rod of cigarette varied from 5.7mg to 13 mg and in a packet of gutkha or khaini from 1.7 to 76.2mg.[12] The odds ratio for developing Nicotine dependence increased after five years of use in smokeless tobacco users when compared to 10 years of smokers probably due to this reason. The higher prevalence of nicotine dependence in both smokers and smokeless tobacco users could be due to the fact that the tobacco users indulged in both forms to increase nicotine delivery due to tolerance and intense craving. Our figure of workers using exclusively smokeless tobacco and with FTND score above 5 was similar to those found in the study of BPO employees in Mumbai.[8] The mean FTND scores in our sample were lesser than the available research data in Indian populations. The reasons could be that the other studies were done on a sample of selected industrial populations or in a rural population in kerala and hence may not be comparable to our sample.[5,8,13]

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design and being limited to industrial workers which limits its generalizability. Underreporting of the tobacco use and the varying strengths of nicotine content in the various smoking and smokeless tobacco products could have affected the identification of actual number of dependents on tobacco in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of tobacco use among the sample of male industrial workers were comparable to that of the general population. A significant number of males in young age group are being initiated into the habit by peer influence and later becoming dependent on nicotine. Restrictions on use of tobacco products in work sites, Awareness programmes on harmful effects of tobacco and the options available for treatment of Nicotine dependence are required to be implemented in worksite to curb this trend.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N, Gomeshtapeh FI, Drope J. Tobacco Atlas. 5th ed. Atlanta (USA): American Cancer Society; 2015. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 06]. Available from: http://www.tobaccoatlas.org . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mishra S, Joseph RiA, Gupta PC, Pezzack B, Ram F, Sinha DN, et al. Trends in bidi and cigarette smoking in India from 1998 to 2015 by age, gender and education. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1:e000005. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper KH, Gey GO, Bottenberg RA. Effects of cigarette smoking on endurance. JAMA. 1968;203:123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.True WR, Heath AC, Scherrer JF, Waterman B, Goldberg J, Lin N, et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to smoking. Addiction. 1997;92:1277–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parashar M, Agarwalla R, Mallik P, Dwivedi S, Patvagekar B, Pathak R. Prevalence and correlates of nicotine dependence among construction site workers: A cross sectional study in Delhi. Lung India. 2016;33:496–501. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.188968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akram S, Gururaj NA, Nirgude AS, Shetty S. A study on tobacco use and nicotine dependence among plywood industry workers in Mangalore city. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2015;4:5729–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansari ZA, Bano SN, Zulkifle M. Prevalence of tobacco use among power loom workers – A cross sectional study. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:34–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mishra GA, Majumdar PV, Gupta SD, Rane PS, Hardikar NM, Shastri SS. Call centre employees and tobacco dependence: Making a difference. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47:s43–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.63860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS 4: 2015-2016) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Mumbai: Indian Institute of Population Sciences; 2016. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/nfhs/factsheet_NFHS-4.shtml . [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Institute for Population Sciences, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Global Adult Tobacco Survey India (GATS India 2009-2010) New Delhi, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 06]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/1455618937GATS%20India.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma MK, Sharma P. Need for validation of Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence in Indian context: Implications for nicotine replacement therapy. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:105–8. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.178768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jayakrishnan R, Mathew A, Lekshmi K, Sebastian P, Finne P, Uutela A. Assessment of nicotine dependence among smokers in a selected rural population in Kerala, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2663–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]