Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Academically typically achieving adolescents were compared with students having academic difficulty on stress and suicidal ideas.

Materials and Methods:

In a cross-sectional study, 75 academically typically achieving adolescents were compared with 105 students with academic difficulty and 52 students with specific learning disability (SLD). Academic functioning was assessed using teacher's screening instrument, intelligence quotient, and National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences index for SLD. Stress and suicidal ideas were assessed using general health questionnaire, suicide risk-11, and Mooney Problem Checklist (MPC). Appropriate statistical methods were applied.

Results:

Three groups were comparable on age, gender, mother's working status, being only child, nuclear family, self-reported academic decline, and type of school. About half of adolescents reported psychological problems on General Health Questionnaire (mean score >3 in all the groups). Academically typically achieving adolescents showed higher stressors in peer relationships, planning for future and suicidal ideation compared to adolescents with academic difficulty. Adolescents face stress regarding worry about examinations, family not understanding what child has to do in school, unfair tests, too much work in some subjects, afraid of failure in school work, not spending enough time in studies, parental expectations, wanting to be more popular, worried about a family member, planning for the future, and fear of the future. Significant positive correlation was seen between General Health Questionnaire scores and all four subscales of MPC. Suicidal ideas showed a negative correlation with MPC.

Interpretations and Conclusions:

Adolescents experience considerable stress in multiple areas irrespective of their academic ability and performance. Hence, assessment and management of stress among adolescents must extend beyond academic difficulties.

Keywords: Academic difficulty, adolescents, specific learning disability, stress, students, suicidal ideas

Adolescence is one of the most stressful periods in development.[1] Adolescents face a host of biological, social, and psychological stressors.[2,3] Expectations of parents and teachers, peer pressure, interpersonal problems, academic stress, worries about the future, and home environment are some of the stressful issues faced by adolescents.[3,4] These stressors could lead to mental health problems including adjustment disorder, anxiety, depression, and suicide.[1,2,3]

Adolescents with academic difficulties generally receive the attention of parents, teachers, and researchers. Although adolescents with academic difficulties face heightened stress,[5,6] adolescents who are typically achieving face stressors as well.[1] Only a few studies on Indian adolescents are available. They show that adolescents face multiple stressors such as criticism from parents, teachers, and peers; interpersonal problems; problems in living conditions and home environment; worries about their future; health and financial status of family members; high parental expectations; and academic worries, to name some.[7,8,9,10,11,12] These stressors are not limited to adolescents with academic difficulty but are faced by typically achieving adolescents as well.[7,8,9,10,11,12]

Authors have not come across any Indian study on the association between stress and suicidal ideas in the case of either academically typical adolescents or adolescents with academic difficulty. The aim of the present study was to assess if academically typically achieving students differ from the students with academic difficulty on psychological problems, stress, and suicidal ideas. Furthermore, the aim of the study was to assess the nature and degree of stressors faced by adolescents using a comprehensive checklist that measures stressors in most areas and not just academic stress. The participants in the present study were drawn from an earlier study conducted to find out the prevalence of specific learning disability or specific developmental disorder of scholastic skills among school students.[13]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and settings

This was a community-based, randomized, cross-sectional study carried out on adolescents from ten randomly chosen schools of Chandigarh, five of these private schools and five were government schools. To have a representative sample, the city was divided into five zones and one government and one private school from each zone was randomly chosen.

Study duration

The study was carried out from April 2008 to May 2009 (1 year).

Sample

157 students having academic difficulty as rated by class teachers on Teacher's Screening Instrument were selected. A control group of 75 academically typically achieving students matched by age, class, and school was used. All these 232 students (157 students with academic difficulty and 75 typically achieving students) were assessed in detail for the presence of intellectual disability[14,15] and specific developmental disorder of scholastic skills.[16] All 232 students had average IQ. Out of 157 students with academic difficulty, 52 were found to have SLD as assessed by National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) index for SLD.[16] We finally had three groups as follows: Group A: students with academic difficulty without SLD (n = 105) (those students who were rated to have academic difficulty as rated by the teacher's screening instrument but were negative on NIMHANS index for SLD); Group B: students having academic difficulty and SLD (n = 52) (those students who were rated as having academic difficulty on the teacher's screening instrument and also had SLD on the NIMHANS index for SLD); and Group C: academically typically achieving students (n = 75) (students matched by age, class, and school who were negative on teacher's screening instrument as well as NIMHANS index for SLD).

Inclusion criteria for the study were:

Students should have been enrolled in the school for at least 6 months

Students should be willing to participate

The parents should give consent for participation.

Exclusion criteria were:

Noncooperative students

Refusal of parents to allow participation

Significant hyperactivity hindering the administration of tests.

After fulfilling inclusion and exclusion criteria and taking written informed consent from the parents and assent from students, the following scales were administered to all the students.

Tools

Sociodemographic proforma

A sociodemographic sheet was prepared to record the sociodemographic details.

Teacher's screening instrument

The teacher's screening instrument has been developed in India to rate academic difficulty from the teacher's view point.[13] This has six questions pertaining to student's academic performance which include frequent unexplained absence from school, below average academic performance, poor writing ability, problems in reading, poor mathematical competence, and problem in recall. The pro forma has been found to have high sensitivity (90.385) and specificity (94.68) in the Indian population.[13] The questions required forced choice (yes or no) response and if teachers reported problems on at least two areas out of six, it was taken as academic difficulty and child was assessed in detail.

General Health Questionnaire

Twelve items (Hindi version) with a cutoff score of 2, giving a sensitivity of 96.7% and specificity of 90%, were used. GHQ is one of the most commonly used instruments to screen for the presence of psychiatric morbidity and has been standardized in many different languages and cultures. The sensitivity and specificity has been found to be high in the Indian population as well.[17]

Mooney problem checklist

High School Form,[18] translated in India by Joshi and Banerji (1979) into Hindi,[19] was used to assess the nature of stress. This is a 40-item Likert type checklist which assesses problems in four areas: (a) Problems - teenagers have in relation to their parents; (b) problems that arise in their role as students; (c) problems that involve their peer relationship; (d) problems that arise as they plan for their future. Each area has ten items. Scores are summed up for each problem area, and average for each problem area was calculated to find out the severity of stress. A rating of twenty on each subscale is taken as cutoff to assess the perceived problem. The Hindi version of the checklist was used in the present study.

Suicide risk eleven

SRE is a self-administered, visual analog scale developed in India by Verma et al.[20] was administered to assess the suicidal risk. It has items ranging from “it is a sin to commit suicide,” “I do not have suicidal thoughts,” and “I have tried suicide many times.” Test–retest reliability was rho 0.95 (P< 0.01).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by Research Committee and Ethics Committee of the Institute. Approval from the District Education Officer and school principals was taken. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of all the students and assent was obtained from the students. The Indian Council of Medical Research ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants were adhered to.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Descriptive and inferential statistics were applied. Comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA and t-test. When quantitative data did not satisfy the parametric criteria, Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U-test were applied.

RESULTS

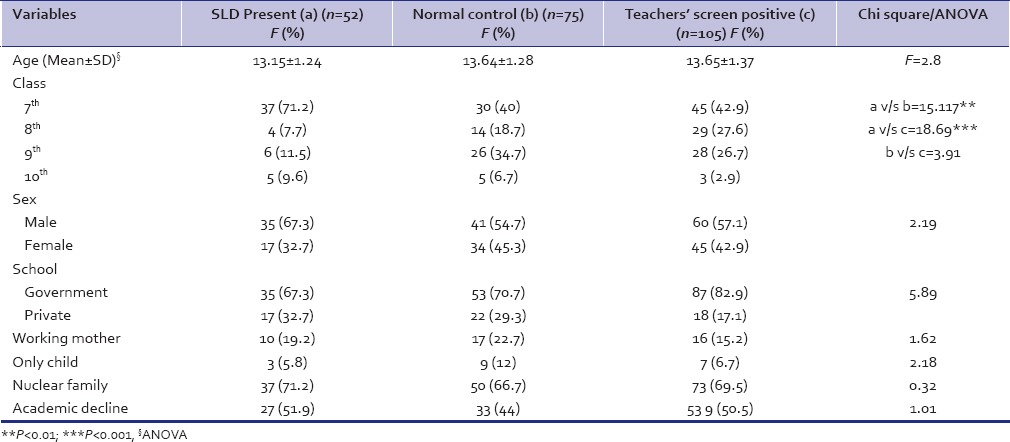

The three groups were comparable on age, gender, mother's working status, being only child, nuclear family, self-reported academic decline, and whether they studied in government or private school [Table 1]. A higher number of children from class 7th were found to be having SLD.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic details of the participants

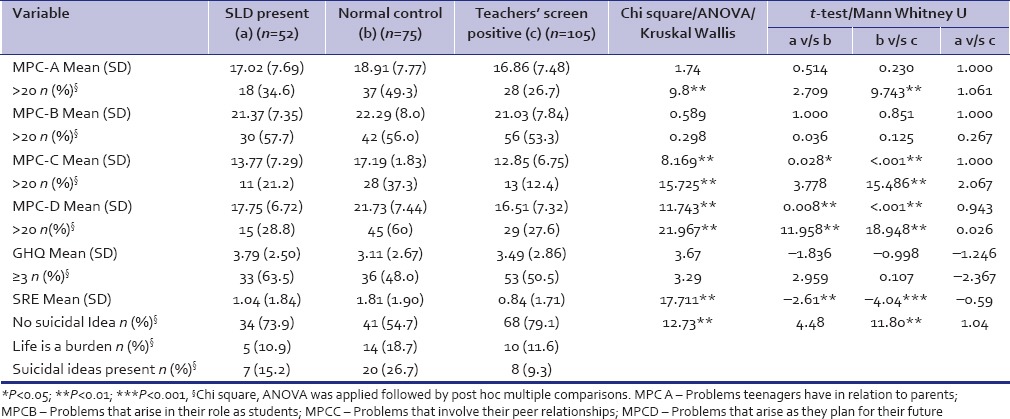

As seen on GHQ 12 [Table 2], nearly half the students showed significant psychological distress in all the three groups irrespective of their academic ability and performance. The mean score of GHQ 12 was more than 3 in all the three groups, and it was not significantly different between the groups.

Table 2.

Comparison on variables associated with stress

The mean score on Mooney Problem Checklist (MPC) A (relation to parents) was statistically similar across the three groups [Table 2]. However, significantly higher number of students in the academically typically achieving group had a mean score of more than 20 as compared to the group with academic difficulty without SLD. The three groups were similar on the MPC B (role as students). On MPC C (problems involving peers) and MPC D (plans for future), academically typically achieving students had significantly higher mean scores as compared to both the other groups. Significantly higher number of students in the academically typically achieving group had scores more than 20 on MPC domain C (problem involving peers) as compared to the group with academic difficulty without SLD. On MPC D (plan for future), number of students with a mean score more than 20 was significantly higher in the academically typically achieving group.

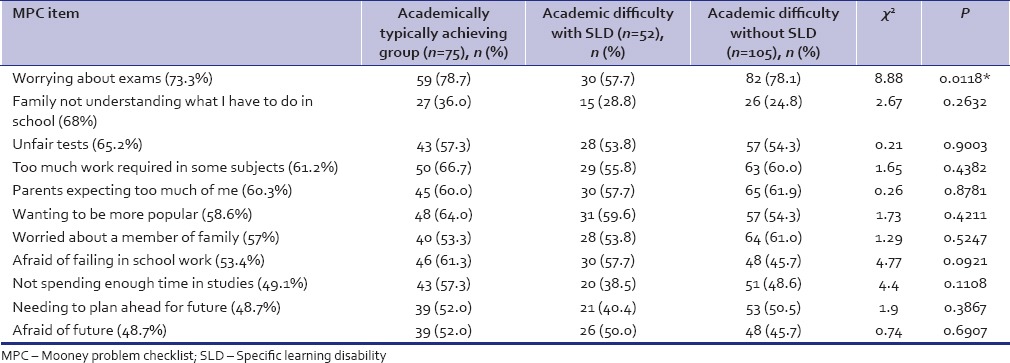

On individual items of MPC [Table 3], items related to academics that were stressful in most adolescents were worry about examinations, family not understanding what child has to do in school, unfair tests, too much work in some subjects, afraid of failure in school work, and not spending enough time in studies. The nonacademic items that were stressful in most adolescents were parental expectations, wanting to be more popular, worried about a family member, planning for the future, and fear of the future. On comparing the three groups on these items, a higher number of academically typically achieving students showed stress related to family not understanding what the child has to do in school, too much work in some subjects, wanting to be more popular and not spending enough time in studies. The difference on individual items was statistically significant only for the item “worrying about examinations”. The number of students having significant stress on this item was significantly higher among academically typically achieving students and students having academic difficulty without SLD as compared to students having academic difficulty and SLD [Table 3].

Table 3.

Significant stressors as reported on mooney problem checklist

Academically typically achieving students showed significantly higher score on suicidal ideas [Table 3] as compared to the groups with academic difficulty. A higher number of students in the academically typically achieving group had suicidal ideas as compared to the other two groups. Suicidal ideas and feelings that life was a burden were reported more by the academically typically achieving group as compared to students having academic difficulty, difference being statistically significant [Table 2].

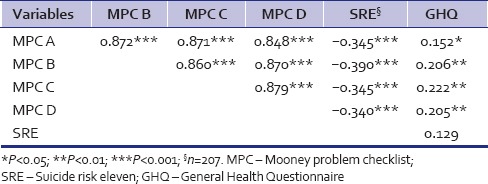

Significant positive correlation was seen between GHQ scores and all subscales of MPC [Table 4]. Suicidal ideas showed a negative correlation with all MPC subscales [Table 4].

Table 4.

Spearman's correlations

DISCUSSION

The present study attempted to investigate the level of stress and suicidal risk among adolescents using MPC which comprehensively taps common stressful issues faced by adolescents. To the best knowledge of authors, this is the first effort to compare academically typically achieving students with students having academic difficulty in India. In addition, a third group of students with SLD was included to assess if SLD causes more stress.

Students were rated by class teachers as they spend considerable time with the students and they are a reliable source of assessing academic difficulty. Assessment of children's problem behaviors by teachers is reported to be better than parents report in predicting future outcomes.[21]

Majority of students (nearly 50% in each group) in the present study showed significant psychological distress as seen by the mean score on GHQ 12 (>3 in each group). Adolescents face significant stress in spite of their academic ability and performance as there was no significant difference between the academically typically achieving students and students having academic difficulty. These findings reiterate that academic difficulty is not the only stressor among adolescents and the period of adolescence is accompanied by multiple stressors which are not generally recognized and are overshadowed by academic performance. Previous Indian studies have also shown that adolescence is accompanied by multiple stressors such as worries about the living conditions, health and financial status of family members, high parental expectations, and academic worries, to name some.[8,9,10,11] The mean score on MPC B (role as students) in all the three groups was high (above cut off score of 20), and more than 50% students in each group were above cutoff (>20). Thus, it does not matter if students are academically good or are facing academic difficulty or have a disorder such as SLD. The present study included students from classes 7th to 10th, a time when most students start thinking about their career. This is also the time when most of the changes in adolescents are taking place and they are prone to stress. It would be very common to face questions at this stage like - “what would you like to be when you grow up?,” “what do you want to do in the future?,” and “do you think you can do as well as your peers?” These questions raise worries in the minds of students and might lead to stress. Parents and teachers have markedly different expectations from students belonging to these three groups. Goals set for students who are not facing problems in academics or doing better will be much higher as compared to children who are not very good in academics. A previous Indian study has also reported that parents and teachers have high expectations from students who are good in academics.[2] This could be one reason that academically typically achieving students experience higher stress than students with academic difficulty in the present study. Recent Indian studies have also shown that adolescents face stress due to high parental expectations,[8] worry about their future, and worry about their careers.[3,11]

Major stressors reported on MPC in the present study were worrying about examinations, family not understanding what the child had to do in school, unfair tests, too much work in some subjects, too many expectations from parents at home, wanting to be more popular, worrying about a family member, afraid of school failure, not spending enough time in studies, and worries about the future. On comparing the groups on individual items of MPC, the typically achieving students showed higher stress than the other groups on family not understanding what child has to do in school, too much work in some subjects, not spending enough time in studies and wanting to be more popular. Many of these stressors are not related to academics. Examples of nonacademic stressors are parental expectations at home, wanting to be more popular, worry about a family member, and worries about the future. It would be fair to assume that all these stressors are not exclusive to students with academic difficulty and would be faced even by academically typically achieving students. This combined with higher parental and self-expectation might lead to higher stress in academically typically achieving students. Previous Indian research has also shown that adolescents face stressors in multiple areas.[2,3,8,11]

It has been previously reported from India that parents lack knowledge about SLD. They do not know that SLD is a lifelong disorder. They refuse to accept the diagnosis of SLD and to avail benefits in the examination for their child as this would hamper future career options.[22] All the students diagnosed as SLD (n = 52) in the present study and their parents were advised to visit the psychiatry OPD for obtaining the certificates for availing benefits in the examination. However, only three families visited the department for obtaining certificate. Although the authors in the present study did not find out the exact reasons for not approaching the department for certification, it could be due to unconcerned attitude, pessimism about the benefits of certification, and lack of knowledge about SLD.

The present study found significantly higher suicidal ideas in academically typically achieving students compared to students having academic difficulty. No previous studies have compared suicidal ideas among students with or without academic difficulty. Indian studies have found a higher level of suicide rates in Indian adolescents as compared to other countries,[23] and there is also a high prevalence of death wishes, suicidal ideation, and suicidal attempts in Indian adolescents.[24] Multiple factors such as unrecognized depression, adjustment issues, home environment, social support, temperamental traits, worrying about future, substance abuse, academic problems, relationship issues, romantic partner problems, and coping styles have been found to play a role in raising level of suicidal ideas, suicide attempts, and suicide among adolescents.[25,26,27,28] Thus, academic difficulty is only one of the factors which might be related to high risk of suicide and other factors also need to be explored. In the present study, the number of adolescents having suicidal ideas was low in all the three groups (7 in the SLD group, 8 in the group having academic difficulty without SLD, and 20 in the academically typically achieving group). The present study is not probably sufficiently powered to report on this issue. The authors reckon that a study with a larger sample is required to assess the relation of academic ability with suicidal ideas.

The research shows that connectedness and perceived closeness to parents are protective against self-harm.[29,30] An Indian study found that adolescents who reported a higher degree of parental involvement in their lives have reduced risk of adverse mental health outcomes.[31] In the present study, though the three groups were statistically similar in mean scores on relationship with parents (Domain A), the scores were higher in the academically typically achieving students. In addition, significantly lesser number of students in the academic difficulty group had mean score above cutoff (20) as compared to typically achieving students. Similarly, the number of students with mean score above cutoff (20) was lesser in the SLD group as compared to typically achieving students though it did not reach statistical significance. Better relations with parents than the academically typically achieving students could have acted as a buffer against suicidal ideas among students with academic difficulty.

Although the present study has many strengths, a few limitations should be kept in mind while interpreting the results. The study is cross-sectional, and sample size is small. The parents were not interviewed to assess the stressors faced at home, parenting style, relationship of adolescents with parents, etc., Additional factors such as coping, temperament, and psychopathology were not studied.

CONCLUSIONS

Adolescence is related to considerable psychological distress irrespective of academic performance. Stress is faced by adolescents irrespective of whether they are doing well in academics or not. Typically achieving students experienced a higher level of stress and suicidal ideas than students having academic difficulty. The problems arise in various areas such as relationship with parents, parental expectations, worrying about future, role as students and peer relationships, and academic difficulties. Thus, assessment of stress among adolescents should extend beyond academic difficulties. Teachers and parents need to be more aware of the multiple issues leading to stress among students to learn ways to handle and guide adolescents.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Chandigarh.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mishra CP, Krishna J. Turbulence of adolescence. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2014;45:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayanthi P, Thirunavukarasu M, Rajkumar R. Academic stress and depression among adolescents: A cross sectional study. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52:217–9. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0609-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew N, Khakha DC, Qureshi A, Sagar R, Khakha CC. Stress and coping among adolescents in selected schools in the capital city of India. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82:809–16. doi: 10.1007/s12098-015-1710-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyer M, Holt DJ, Pedrelli P, Fava M, Ameral V, Cassiello CF, et al. Factors that distinguish college students with depressive symptoms with and without suicidal thoughts. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2013;25:41–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi M, Gumashta R, Kasturwar NB, Deshpande AV. Academic anxiety a growing concern among urban mid adolescent school children. Int J Biol Med Res. 2012;3:2180–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain A, Kumar A, Husain A. Academic stress and adjustment among high school students. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2008;34:70–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arun P, Chavan BS. Stress and suicidal ideas in adolescent students in Chandigarh. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63:281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deb S, Chatterjee P, Walsh K. Anxiety among high school students in India: Comparisons across gender, school type, social strata and perceptions of quality time with parents. Aust Educ Dev Psychol. 2010;10:18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latha KS, Reddy H. Patterns of stress, coping styles and social supports among adolescents. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2006;3:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augustine LF, Vazir S, Rao SF, Rao MV, Laxmaiah A, Nair KM. Perceived stress, life events & coping among higher secondary students of Hyderabad, India: A pilot study. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:61–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy AV. Problems of concern for many of the school going adolescents. India Psychol Rev. 1989;18:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou L, Fan J, Zhou YD. Cross-sectional study on the relationship between life events and mental health of secondary school students in Shanghai, China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24:162–71. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arun P, Chavan BS, Bhargava R, Sharma A, Kaur J. Prevalence of specific developmental disorder of scholastic skill in school students in Chandigarh, India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:89–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malin AJ. Manual for Malin's Intelligence Scale for Indian Children (MISIC) Lucknow: Indian Psychological Corporation; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raven JC. Guide to the Standard Progressive Matrices. London: HK Lewis; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapur M, John A, Rozario J, Oommen A. NIMHANS index of specific learning disabilities. In: Hirisave U, Oommen A, Kapur M, editors. Psychological Assessment of Children in the Clinical Setting. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences; 1991. pp. 72–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacob KS, Bhugra D, Mann AH. The validation of 12-item General Health Questionnaire among ethnic Indian women living in the United Kingdom. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1215–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooney RL, Gordon LV. The Mooney Problem Check Lists. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi MC, Banerji S. Psychodynamics of some psychosomatic disorders using mooney problem checklist. J Rajasthan Psychiatr Soc. 1979;2:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verma SK, Nehra A, Kaur R, Puri A, Das K. Suicide Risk Eleven: A Visual Analogue Scale. Varanasi: Rupa Psychological Centre; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhulst FC, Koot HM, Van der Ende J. Differential predictive value of parents’ and teachers’ reports of children's problem behaviors: A longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1994;22:531–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02168936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karande S, Mehta V, Kulkarni M. Impact of an education program on parental knowledge of specific learning disability. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61:398–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaron R, Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil J, George K, Prasad J, et al. Suicides in young people in rural Southern India. Lancet. 2004;363:1117–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidhartha T, Jena S. Suicidal behaviors in adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:783–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02790385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bearman PS, Moody J. Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:89–95. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Tein JY, Zhao Z, Sandler IN. Suicidality and correlates among rural adolescents of China. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Cheung AH. An observational study of bullying as a contributing factor in youth suicide in Toronto. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:632–8. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karch DL, Logan J, McDaniel DD, Floyd CF, Vagi KJ. Precipitating circumstances of suicide among youth aged 10–17 years by sex: Data from the national violent death reporting system, 16 states, 2005–2008. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53 1 Suppl:s51–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blum RW, Kelly A, Ireland M. Health-risk behaviors and protective factors among adolescents with mobility impairments and learning and emotional disabilities. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:481–90. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svetaz MV, Ireland M, Blum R. Adolescents with learning disabilities: Risk and protective factors associated with emotional well-being: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:340–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasumi T, Ahsan F, Couper CM, Aguayo JL, Jacobsen KH. Parental involvement and mental well-being of Indian adolescents. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:915–8. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]