Abstract

Background:

Shift-workers commonly suffer from insomnia. This study evaluates different domains of insomnia.

Aim:

This study was aimed to study sleep and insomnia in rotating shift-workers and compare with day-workers.

Materials and Methods:

This was case–control study. The sleep of rotating shift-workers is compared with day workers using Athens Insomnia Scale.

Results:

Rotating shift-workers had significantly higher scores on Athens insomnia scale on domains of initial, intermediate and terminal insomnia than day workers. Duration and quality of sleep and sense of well-being are lower in rotating shift-workers. Rotating shift-workers also experienced more day-time sleepiness than day workers. However, there was no difference in perceived physical and mental functioning between the two groups.

Conclusion:

Individuals working in rotating shifts for more than 15 days have significantly higher prevalence of insomnia than day-workers.

Keywords: Athens Insomnia Scale, insomnia, shift-work

Sleep may be defined as a rapidly reversible state of reduced mobility and sensory awareness.[1] Most humans spend roughly a third of their lives asleep, but physicians and physiologists frequently overlook this time. Sleep is an important and complex physiologic process requiring the proper function of multiple diverse brain regions. These structures should work together electrically and chemically in a network to facilitate sleep. If neurologic diseases affect these regions, the process can be disrupted with significant consequences.[2]

It has been observed that shift-workers suffer from insomnia when attempting to sleep and excessive sleepiness when attempting to remain awake. This is important since the number of people working in shifts has been increasing steadily for decades.[3] There is not much Indian research carried out on shift-work disorders. This study evaluates different domains of insomnia in shift-workers.

In this study, we attempt to answer the following research questions: (a) What is the pattern of sleep in persons working in rotating shifts? (b) What is the predominant type of insomnia in persons working in rotating shifts? and (c) How does sleep in persons working in rotating shifts differ from those not working in shifts?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This case–control study was carried out at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Study was conducted over 7 months in the year 2012. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and controls.

The study group contained 33 healthy males who were on attendant duty for the patients for at least 15 days. There are usually three serving personnel assigned duties as attendants for every patient, who worked in 6 hourly shifts. Each person got his next duty after 12 h later. Individuals with a history of psychiatric illness, history of traumatic brain injury, seizures and loss of consciousness, any chronic medical illness and history of drug abuse other than alcohol and tobacco were excluded. To avoid selection bias, all attendants meeting criteria were included in the study. The subjects were all male patients in the age range of 22 years to 49 years. Controls were age and education-matched male medical assistants who had worked in day shift for at least previous 15 days. After applying same exclusion criteria as that of the study group, controls were recruited for the study.

The Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) was used to assess sleep of the subjects. It is based on International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria and was validated by Soldatos et al.[4] The AIS is a self administered inventory consisting of 8 items; 5 items assess difficulty with sleep induction, awakening during the night, early morning awakening, total sleep time, and overall quality of sleep and 3 items pertaining to the next-day consequences of insomnia (problems with sense of well-being, overall functioning, and sleepiness during the day).[4] A cut-off value of 10 to determine those suffering from insomnia among the general population was chosen since it provides us with the highest positive predictive value of 90% while still offering a high negative predictive value of 94%.[5]

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA), version 20.0. To check for normality, the Shapiro-Wilk test was applied. The study group was compared with the control group using the Mann Whitney U Test since the data did not have a normal distribution.

RESULTS

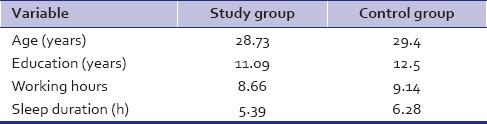

As shown in Table 1, analysis of baseline profile revealed that the mean age of study group and control group was 28.73 years and 29.4 years, respectively. Although the average years of education in the study group was lower than in control group, this difference was not statistically significant. Average working hours in the study group were 8.66 as compared to 9.14 in control group. Average sleep duration in the study group was 5.39 h, and that of the control group was 6.28 h. This difference was statistically significant.

Table 1.

Baseline profile of subjects

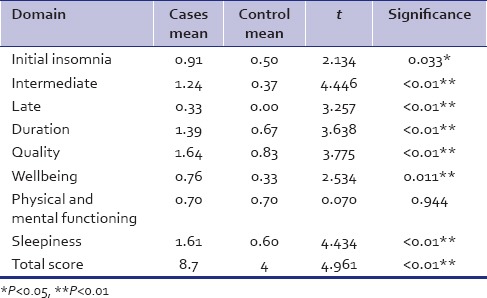

Table 2 shows that study group had significantly higher scores on the AIS in domains of initial, intermediate and terminal insomnia. Duration, quality and sense of wellbeing were significantly lower in the study group. Shift-workers also experienced more day-time sleepiness. However, there was no difference in perceived physical and mental functioning.

Table 2.

Comparison of domains of insomnia of study group to control group on Athens insomnia scale

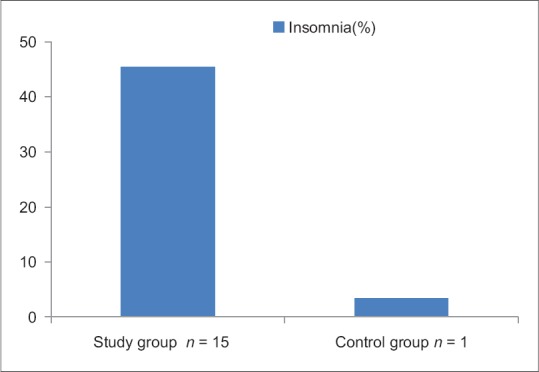

As shown in Figure 1, the prevalence of insomnia was 45.45% in the study group as compared to 3.33% in control group with AIS cut off 10.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Insomnia among the study and control group

DISCUSSION

This study found a prevalence of insomnia of 45% in rotating shift-workers. Similarly, a study done by Drake et al.[6] also reported that 32.1% and 26.1% of night-shift and rotating-shift workers, respectively, met their pre-specified excessive sleepiness and/or insomnia criteria. A study using the Multiple Sleep Latency Test in a population of shift-working, long-haul bus drivers reported that the criteria for excessive sleepiness were met by 38% to 42% of subjects.[7]

The study results are also in agreement with Härmä et al.,[8] who found that shift-work is associated with increased subjective, behavioral, and physiological sleepiness. Sleepiness is particularly pronounced during the night shift and may terminate in actual incidents of falling asleep at work. In some occupations, this clearly constitutes a hazard that may endanger human lives and have large economic consequences. These risks clearly involve a large number of workers and are of significance to society. Factors that influence the ability to cope with shift work include age, type of work schedule, domestic responsibilities, diurnal preference, and commute time and these may contribute to differences in prevalence in various studies.

The study results are in concordance with a study done by Puca et al.[9] which found poor quality of life in shift-workers. Further, Takahashi et al.[10] found that quality of life in shift-workers depends on the adaptation to shift-work.

The results obtained in our study can be explained with the help of findings of Gumenyuk et al.[11] who observed that there is an internal physiological delay of the circadian pacemaker in asymptomatic night-shift workers. In contrast, individuals with shift-work disorder (SWD) maintain a circadian phase position similar to day workers, leading to a mismatch between their endogenous rhythms and their sleep-wake schedule. However, there was no significant difference found in the perceived physical and mental functioning in rotating shift-workers and day-workers. It may be due to apparent lack of psychological mindedness of study group or adaptation to shift-work schedule.

SWD results when individuals are required to work and sleep at times that are in opposition to the circadian propensity for sleep and alertness, leading to symptoms of insomnia and excessive sleepiness. Individuals may complain of problems initiating and maintaining sleep as they are attempting to sleep at a time of low circadian sleep propensity. Symptoms of insomnia and excessive sleepiness may persist for several days after the last night shift or on days off, even after sleep has been restored to conventional times. This continued difficulty is possibly due to a partial adjustment of the circadian system. Successful adaptation to shift work is influenced by the number of consecutive night shifts and the speed and direction of the shift rotation.[12]

The goal of intervention is to improve sleep quality, alertness, performance at work, and overall quality of life. The ideal approach is to ensure good sleep hygiene and to realign circadian rhythms with the work schedule. Modafinil is the drug recently approved for shift-work sleep disorder. Short-acting hypnotic medications can be used to treat associated insomnia, but they are not yet approved specifically for the treatment of SWD.[13,14,15]

This study compared rotating shift-workers with a control group in case-control design. This is one of the few Indian studies in which different domains of insomnia studied. This study had the small sample size and only male patients were studied. The total duration of shift work was not considered in this study and polysomnography was not included.

CONCLUSION

The present study reveals the higher prevalence of insomnia among rotary shift workers. In view of above finding further research is needed to find the workers disability. We also need to address workers concerns by behavioral and psychotherapeutic measures. We propose every shift workers should undergo insomnia related disability assessment to increase productivity and to prevent untoward incidences at work site.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel JM. Do all animals sleep? Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:208–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moszczynski A, Murray B. Neurobiological aspects of sleep physiology. Sleep. 2012;30:963–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirshkowitz M, Seplowitz-Hafkin R, Sharafkhaneh A. 9th ed. New Delhi: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Sleep disorders. Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry; pp. 2150–77. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens insomnia scale: Validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:555–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:263–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Walsh JK, Roth T. Shift work sleep disorder: Prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep. 2004;27:1453–62. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos EH, de Mello MT, Pradella-Hallinan M, Luchesi L, Pires ML, Tufik S, et al. Sleep and sleepiness among Brazilian shift-working bus drivers. Chronobiol Int. 2004;21:881–8. doi: 10.1081/cbi-200035952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Härmä MI, Hakola T, Akerstedt T, Laitinen JT. Age and adjustment to night work. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51:568–73. doi: 10.1136/oem.51.8.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puca FM, Perrucci S, Prudenzano MP, Savarese M, Misceo S, Perilli S, et al. Quality of life in shift work syndrome. Funct Neurol. 1996;11:261–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi M, Tanigawa T, Tachibana N, Mutou K, Kage Y, Smith L, et al. Modifying effects of perceived adaptation to shift work on health, wellbeing, and alertness on the job among nuclear power plant operators. Ind Health. 2005;43:171–8. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.43.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gumenyuk V, Roth T, Drake CL. Circadian phase, sleepiness, and light exposure assessment in night workers with and without shift work disorder. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29:928–36. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.699356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barion A, Zee PC. A clinical approach to circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Sleep Med. 2007;8:566–77. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart CL, Ward AS, Haney M, Foltin RW. Zolpidem-related effects on performance and mood during simulated night-shift work. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:259–68. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart CL, Haney M, Nasser J, Foltin RW. Combined effects of methamphetamine and zolpidem on performance and mood during simulated night shift work. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:559–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Camp RO. Zolpidem in fatigue management for surge operations of remotely piloted aircraft. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2009;80:553–5. doi: 10.3357/asem.2460.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]