Abstract

Baicalin is a traditional Chinese herbal medicine commonly used for hair loss, the precise molecular mechanism of which is unknown. In the present study, the mechanism of baicalin was investigated via the topical application of baicalin to reconstituted hair follicles on mice dorsa and evaluating the effect on canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the hair follicles and the activity of dermal papillar cells. The results indicate that baicalin stimulates the expression of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7 and disheveled 2 whilst inhibiting the Axin/casein kinase 1α/adenomatous polyposis coli/glycogen synthase kinase 3β degradation complex, leading to accumulation of β-catenin and activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In addition, baicalin was observed to increase the alkaline phosphatase levels in dermal papillar cells, a process which was dependent on Wnt pathway activation. Given its non-toxicity and ease of topical application, baicalin represents a promising treatment for alopecia and other forms of hair loss. Further studies of baicalin using human hair follicle transplants are warranted in preparation for future clinical use.

Keywords: baicalin, canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling, alkaline phosphatase, reconstituted hair follicle, dermal papillar cells

Introduction

Hair is one of the unique characteristics of mammals and is a marker of individual health as it serves multiple physiological functions, including protecting the body from environmental insults and providing thermal regulation (1). Alopecia, or spot baldness, is a common and incurable disease that can appear early in life, for which there are limited treatment options (2). Traditional Chinese herbal medicines, including Scutellaria baicalensis have been used as treatments for hair loss and may be advantageous as they are safe, have minimal toxicity and fewer side effects, and are economical. Baicalin is an active ingredient that is found in several species in the genus Scutellaria, including Scutellaria baicalensis (3). It has also been reported that Baicalin exerts potent biological activities, including antiviral (4) and antitumor effects (5). A study by Shin et al (6) revealed that topical use of baicalin promoted anagen induction in C57BL/6 mice by increasing the activity of dermal papilla cells. Another study by a Chinese research group demonstrated that baicalin promotes the growth of cultured human scalp hair follicles in vitro, likely by inducing the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from dermal papilla cells (7). Baicalin has been reported to activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and increase the activity of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in dermal papillar cells (DPCs), which facilitates their differentiation (6,8). In the present study, a novel model was devised by dissecting the dermis and epidermis of neonatal mice, obtaining single cells from each and then grafting the mixture of cells onto the dorsa of immunodeficient mice in specified proportions (9). This reconstituted model of mouse hair follicle growth accurately simulates the induction, organogenesis and cell differentiation stages of hair follicle morphogenesis (10,11). In order to elucidate the molecular mechanism(s) underlying baicalin-induced hair growth, baicalin was applied topically to the reconstituted hair follicles and its effects on canonical Wnt signaling and dermal papilla cell activity was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Animal experiments

A total of 45 6-week-old female BALB/c-nu mice (weight, 18–20 g) were purchased from Vital River Corporation (Beijing, China) and housed at a constant temperature (23°C) and humidity (55%) with a 12 h light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. A total of 45 1-day-old female C57BL/6 mice (mean weight, 1.3±0.21 g) were purchased from the Centre of Disease Control of Hubei Province (Wuhan, China) and housed as above. Dermal and epidermal cells were isolated from skin of C57BL/6 mice grafted to excision wounds on the dorsa of BALB/c-nu mice in a 1:1 ratio, on which a silicon chamber (cylindrical shape, 20 mm inner diameter and 19.07 mm height, with a 2.5 mm hole bored through the top; Cole Equipment Co., Ormond Beach, FL, USA) was implanted as described previously (9,10). The number of dermal and epidermal cells injected into a silicon chamber was 2.5×106 each. All procedures followed the protocols described previously (9,10). Following surgery, BALB/c-nu mice were divided into five groups: The negative control group, treated with vehicle; the positive control group, treated with 100 μmol of Minoxidil (Wuhan Galaxy Pharmaceutical Chemical Raw Materials Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China); the B50 group, treated with 50 μmol of baicalin (Chengdu Must Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Chengdu, China); the B100 group, treated with 100 μmol of baicalin; and the B + IWR-1 group, treated with 100 μmol baicalin + 1 μmol IWR-1 (Sigma Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). All reagents were dissolved in 50% ethanol in PBS. An equal amount of the aqueous solution (50% ethanol in PBS) was used as the vehicle control. At 1 week post-surgery, the domes of the silicon chambers were removed. At 2 weeks post-surgery, when black hair began to emerge on the dorsa of the mice, the treatments were initiated by applying 100 μl of respective treatment solutions or vehicle to the wound site once daily for 2 weeks. Images were captured 0, 14 and 28 days following grafting. On day 28 the mice were sacrificed and the dorsal skins were harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 48 h. The number of hair follicles in the 10×10 mm wound site was quantified using ImageJ densitometry software ImageJ (Version 1.46r; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). All experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wuhan University Laboratory Animal Research Center (Wuhan, China; permit number: 11203A).

Histology

Formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded dorsal skins were hydrated with ethanol and 4 μm sections were cut longitudinally along the hair follicles, which were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for 5 and 2 min at room temperature, respectively. Digital images were captured using a Nikon E100 light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at ×100 and ×200 magnification.

Histochemistry

Cryosections (6 μm) were placed in deionized water for 5 min at 20°C, and stained using the BCIP/NBT kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) at room temperature for 30 min according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Digital images captured using an Olympus BX53 light microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at ×40 and ×100 magnification.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the skin tissues using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA (2.5 μg) was reverse-transcribed (25°C for 5 min, 50°C 15 for min, 85°C for 5 min and 4°C for 10 min) using the HiScript Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H) kit (Vazyme, Piscataway, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In order to determine the internal control (β-actin), the semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the following temperature protocol: Denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 56°C for 30 sec, extension at 72°C for 25 sec for 30 cycles, and a final extension at 72°C for 4 min. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR-Green Master Mix (Vazyme). Thermoycling conditions were as follows: 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The following primers were used: β-actin, forward 5′-CACGATGGAGGGGCCGGACTCATC-3′ and reverse 5′-TAAAGACCTCTATGCCAACACAGT-3′; Wnt3a, forward 5′-GGGGATTTCCTCAAGGACAAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-TTAGGTTCGCAGAAGTTGGGTG-3′; Wnt5a, forward 5′-AAAGGGAACGAATCCACGCTAA-3′ and reverse 5′-CCAGACACTCCATGACACTTACAG-3′; frizzled 7, forward 5′-GGCGTCTTCAGCGTGCTC TAC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCCACGATCATGGTCATCAGGTAC-3′; disheveled 2, forward 5′-CCATCCCAAACGCCTTTCTAG-3′ and reverse 5′-AGTAATCTTGTTGACGGTGTGC-3′; glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3β, forward 5′-ATCCTTATCCCTCCACATGCTCG-3′ and reverse 5′-CGTTATTGGTCTGTCCACGGTCT-3′; β-catenin, forward 5′-GTGCTGGTGACAGGGAAGACA-3′ and reverse 5′-GGATGGTGGGTGCAGGAGTTT-3′; lymphoid enhancing binding factor 1 (LEF1), forward 5′-ATCAAATAAAGTGCCCGTGGTGC-3′ and reverse 5′-CTGGACATGCCTTGCTTGGAGTT-3′; and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), forward 5′-GCAAGGACATCGCATATCAGCTAA-3′ and reverse 5′-TTCAGTGCGGTTCCAGACATAG-3′. Differences between the samples and controls were analyzed by RT-qPCR using amplification curve. The relative amount of mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method with β-actin as the reference gene (12).

Western blotting

The nuclear and cytoplasmic reagent kit (KGP150; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) was used to extract nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A total of 40 μg per lane was separated by % SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 2 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against the following: β-actin (BM0627; 1:200), lamin (BA1228; 1:200), Wnt3a (BA2628-2; 1:300), Wnt5a (155184-1-AP; 1:1,000) frizzled 7 (16974-1-AP; 1:2,000), disheveled 2 (12037-1-AP; 1:2,000), GSK3β 1 (22104-1-AP; 1:2,000), β-catenin (51067-2-AP; 1:5,000) LEF1 (14972-1-AP; 1:500) and ALP (11400-1-AP; 1:1,000; all Wuhan Proteintech Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (BA1051; 1:50,000; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) were used as the secondary antibody and were incubate with the membrane at room temperature for 2 h. The membranes were washed five times for 5 min each time with TBST, and developed using an ECL Plus kit (NCI5079; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The relative band densities were determined using a BandScan system version 4.30 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance with a post hoc Student-Newman-Keul test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

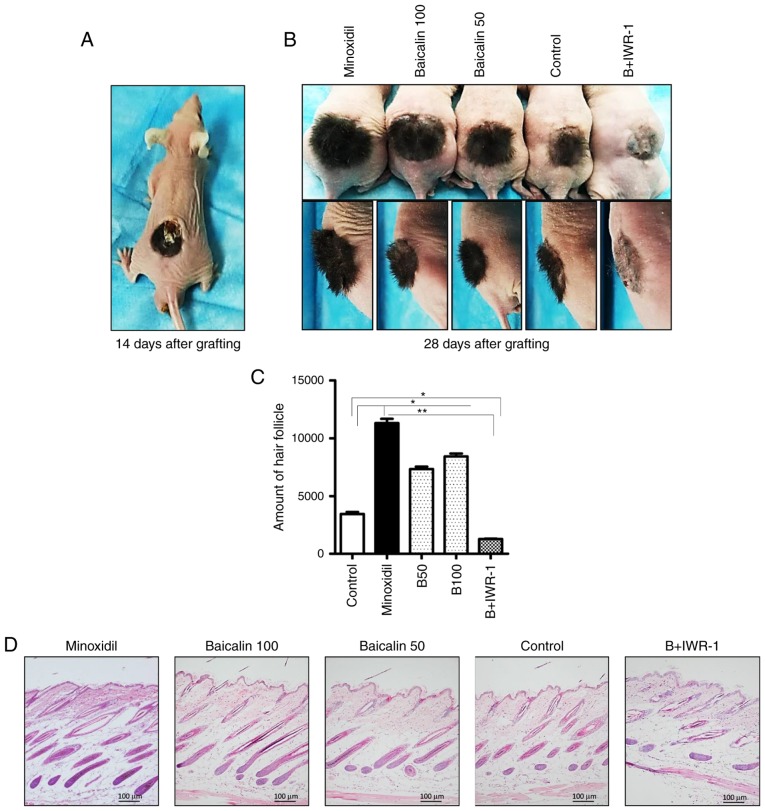

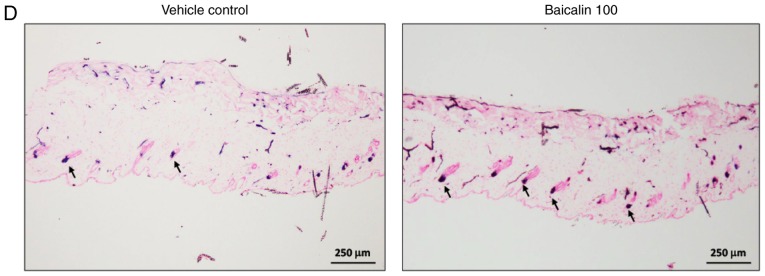

Effects of baicalin on the morphology of developing hair follicles

The progression of hair follicle development in mice was evaluated by images captured on the day of grafting and 14 and 28 days following engraftment. The hair shaft emerged on the mice dorsa at 14 days post-engraftment (Fig. 1A). This point represents the initiation of the anagen stage of the hair follicle cycle, at which point the treatment regime was begun. On day 28, following 14 days of treatment, the content of the hair shafts was significantly increased in the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control group (Fig. 1B and C). The baicalin + IWR-1 group exhibited significantly fewer hair shafts compared with the control (Fig. 1B and C), which was expected as Wnt signaling is inhibited by IWR-1 (13). To further assess the number and size of hair follicles, skin biopsy sections were obtained from the mice and stained with H&E. The skin biopsy analysis confirmed that the number and size of hair follicles were markedly increased in the B50, b100 and Minoxidil-treated group compared with the control group, whereas the B + IWR-1 group had the fewest and smallest hair follicles (Fig. 1D). No apparent differences in the histology were observed between the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups, although both were distinguishable from the control and B + IWR-1 groups (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Morphological features of hair follicles on mice dorsa. Female BALB/c-nu mice were grafted with isolated dermal and epidermal cells from the skin of C57BL/6 mice. A 2 weeks post-grafting, the appropriate topical treatments were applied once daily to mice in each group. (A) Representative image of a mouse on day 14 following engraftment, pre-treatment. (B) Representative frontal and lateral images of mice in the Minoxidil, B100, B50, control and B + IWR-1 groups on day 28 following engraftment. (C) The number of hair follicles in each group. (D) Representative histological images of hematoxylin and eosin stained dorsal skin sections (magnification, ×100). Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean from 3 independent experiments. Control mice were treated with the vehicle only. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. Minoxidil, 100 μmol Minoxidil treatment; B50, 50 μmol baicalin treatment; B100, 100 μmol baicalin treatment; B + IWR-1, 100 μmol baicalin and 1 μmol IWR-1 treatment.

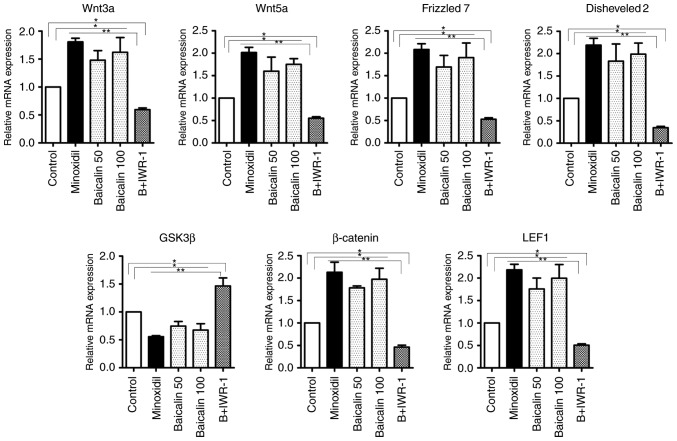

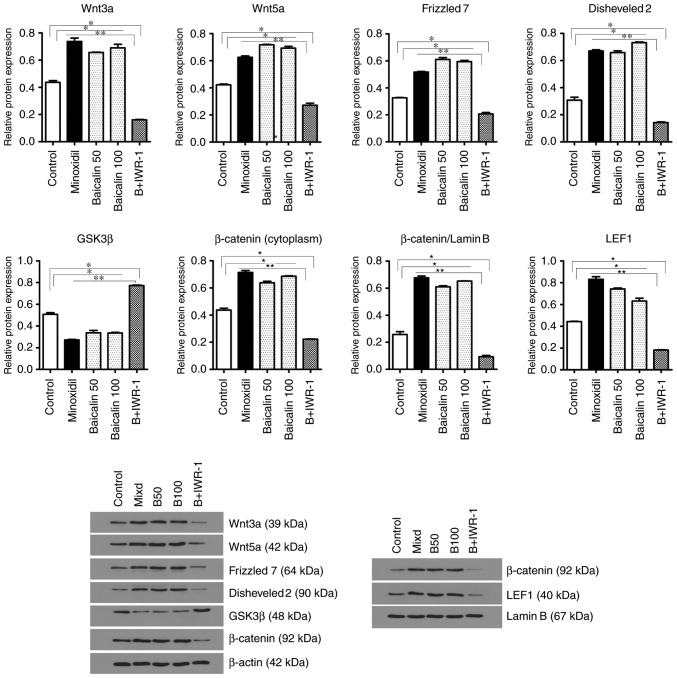

Baicalin modulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in mice

To determine whether baicalin modulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in developing hair follicles, the expression of pathway components were measured at the mRNA and protein levels. The mRNA levels of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7, disheveled 2, β-catenin and LEF1 were significantly increased in the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control and B + IWR-1 groups, whereas the mRNA level of GSK3β was significantly decreased in the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control and B + IWR-1 groups (Fig. 2). Western blotting results were similar to the mRNA levels, as protein levels of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7, disheveled 2, β-catenin (cytoplasmic and nuclear) and LEF1 were significantly increased in the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control and B + IWR-1 groups, whereas the level of GSK3β protein was significantly decreased in the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control and B + IWR-1 groups (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of baicalin on the expression of genes associated with hair growth in reconstituted mouse skin tissue. Levels of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7, disheveled 2, GSK3β, β-catenin and LEF1 mRNA in reconstituted mouse skin tissue as measured using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Control mice were treated with the vehicle only. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; LEF, lymphoid enhancing binding factor; Minoxidil, 100 μmol Minoxidil treatment; B50, 50 μmol baicalin treatment; B100, 100 μmol baicalin treatment; B+IWR-1, 100 μmol baicalin and 1 μmol IWR-1 treatment.

Figure 3.

Effects of baicalin on the expression of genes associated with hair growth in reconstituted mouse skin tissue. Levels of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7, disheveled 2, GSK3β, β-catenin and LEF1 protein in reconstituted mouse skin tissue as measured using western blotting. Control mice were treated with the vehicle only. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; LEF, lymphoid enhancing binding factor; Minoxidil, 100 μmol Minoxidil treatment; B50, 50 μmol baicalin treatment; B100, 100 μmol baicalin treatment; B+IWR-1, 100 μmol baicalin and 1 μmol IWR-1 treatment.

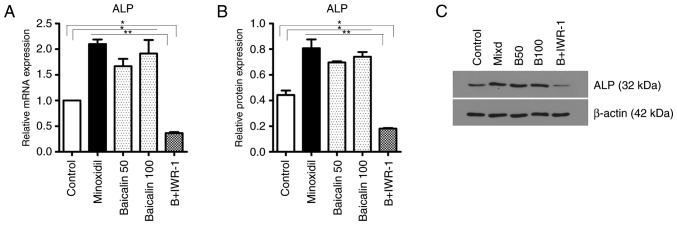

Baicalin upregulates the activity of DPCs in mice

ALP is a marker of DPCs and its expression level is representative of the activity of DPCs. The mRNA levels of ALP were significantly increased in the skin tissues of mice in the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control and B + IWR-1 groups (Fig. 4A). The level of ALP was also significantly increased in the skin tissues of the B50, B100 and Minoxidil-treated groups compared with the control and B + IWR-1 groups (Fig. 4B and C). Furthermore, and consistent with the prior results, ALP activity in hair follicles as detected by staining was markedly increased in the B100 compared with the control group (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Baicalin upregulates the activity of dermal papillar cells in reconstituted mouse skin tissue. Levels of ALP (A) mRNA and (B) protein in reconstituted mouse skin tissue as measured using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and western blotting, respectively. Western blot band intensities were quantified using densitometry and ALP levels normalized to β-actin levels. (C) Representative western blots of ALP and β-actin in mouse skin tissue. (D) Histochemical analysis of ALP activity in hair follicles control and B100 groups was performed using a BCIP/NBT kit (magnification, ×40). Arrows indicate the ALP-positive cells. Control cells were treated with the vehicle only. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01. ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Minoxidil, 100 μmol Minoxidil treatment; B50, 50 μmol baicalin treatment; B100, 100 μmol baicalin treatment; B+IWR-1, 100 μmol baicalin and 1 μmol IWR-1 treatment.

Discussion

Alopecia is a common and incurable disease that affects ~2% of all people worldwide at some point in their lifetime, for which there is currently no effective treatment (14). Based on its pharmaceutical properties and hair follicle growth promoting activity, baicalin, a primary active constituent of the traditional Chinese herbal medicine Scutellaria baicalensis may be an effective alopecia treatment. In the present study, baicalin was topically applied to reconstituted hair follicles on mice dorsa to investigate its effects on canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling as well as its effects on DPCs. The dosages of baicalin selected 50 and 100 μmol were based on a previous study (6), in which dosages of 5 to 100 μmol baicalin were found to be nontoxic to DPCs as assessed using an MTT cell viability assay. The administration of Minoxidil and IWR-1, which is an antagonist of Wnt signaling, was also performed in accordance with prior reports (15,16).

The results of the present study demonstrate that baicalin promotes the growth of hair follicles likely via activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and increasing the ALP activity of DPCs in mice. Furthermore, baicalin was not able to overcome the Wnt/β-catenin signaling antagonism or ameliorate the inhibition of hair follicle growth caused by IWR-1 in mice. This supports the hypothesis that baicalin promotes hair follicle development by activating the Wnt pathway.

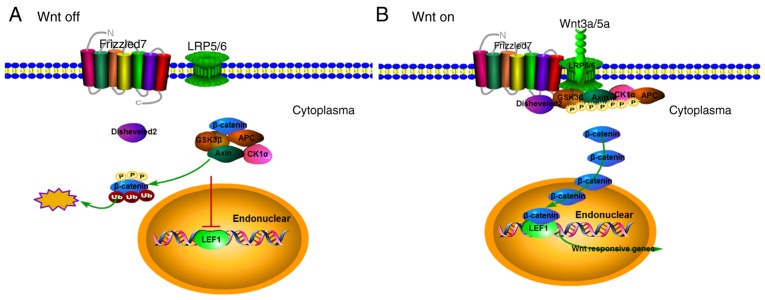

Wnt pathway activity is essential for hair follicle development and the hair cycle (17–20). The canonical Wnt pathway depends on intracellular β-catenin, whose signal transduction cascade components in the hair follicle include Wnt proteins, frizzled receptors and the co-receptor low-density lipoprotein receptor (LRP)5/6, disheveled proteins, the multicomponent degradation complex [comprising Axin, casein kinase (CK)1α, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and GSK3β], β-catenin and transcription factor (TCF)/LEF (21). In the absence of Wnt ligands, the Axin/CK1α/APC/GSK3β degradation complex phosphorylates cytoplasmic β-catenin, leading to ubiquitin-dependent degradation of β-catenin (Fig. 5A). When extracellular Wnt ligands bind to the transmembrane frizzled receptors and co-receptors LRP5/6, disheveled proteins bind to the intracellular domains of the receptors, sequestering and inducing LRP5/6-mediated phosphorylation of the multicomponent degradation complex and leading to β-catenin stabilization (Fig. 5B). Once β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm, it translocates into the nucleus where it acts as a transcriptional co-activator for the TCF/LEF transcription factors, inducing the expression of Wnt pathway target genes (22,23).

Figure 5.

The canonical Wnt pathway regulates gene expression by modulating β-catenin levels. (A) In the absence of Wnt ligands, the Axin/CK1α/APC/GSK3β degradation complex binds and phosphorylates cytoplasmic β-catenin, leading to ubiquitin-dependent degradation of β-catenin. This prevents the accumulation of β-catenin and keeps Wnt pathway target gene expression switched off. (B) Upon binding of extracellular Wnt ligands to transmembrane frizzled receptors and the co-receptors LRP5/6, the Axin/CK1α/APC/GSK3β degradation complex is diverted to the plasma membrane and binds to LRP5/6. Wnt ligand binding also causes disheveled to interact with frizzled receptors and LRP5/6. Phosphorylated LRP5/6 and disheveled then sequester and induce phosphorylation of the Axin/CK1α/APC/GSK3β degradation complex, which inhibits its ability to phosphorylate β-catenin, leading to β-catenin stabilization and accumulation in the cytoplasm. Accumulated β-catenin is then able to translocate into the nucleus and bind to TCF/LEF, activating the expression of the Wnt pathway target genes. CK, casein kinase; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; LRP, low-density lipoprotein receptor; TCF, transcription factor; LEF, lymphoid enhancing binding factor.

In the present study, Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7, disheveled 2, GSK3β, β-catenin and LEF1 were selected for analysis as they are known to be associated with hair follicle development (24). The data herein demonstrates that baicalin treatment increases canonical Wnt pathway signaling in mouse skin tissues by increasing the levels of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, frizzled 7, disheveled 2, β-catenin and LEF1, while decreasing the expression of the β-catenin degradation complex member GSK3β. The resulting activation of canonical Wnt pathway signaling is the likely mechanism by which baicalin stimulates hair follicle growth, as treatment with the Wnt pathway inhibitor IWR-1 blocked baicalin-mediated Wnt pathway activation and hair follicle growth enhancement. IWR-1 blocks canonical Wnt pathway signaling by stabilizing Axin proteins and thereby increasing the activity of the β-catenin destruction complex (25). As co-treatment with IWR-1 prevented baicalin from decreasing the level of GSK3β and activating Wnt signaling, baicalin must act upstream from the destruction complex to activate the canonical Wnt pathway and stimulate hair follicle development.

The hair follicle is comprised of epidermal and dermal compartments, whose reciprocal interactions are considered to be key regulators of hair follicle development and the hair cycle (19). Although the crosstalk between these compartments is complex, DPCs are thought to be the inducers and epidermal cells to be the responders in hair follicle formation and the hair cycle (26–28). As a marker of DPCs, ALP is believed to indicate the induction of hair follicle growth and its activity changes coincide with the hair cycle (29,30). Therefore, it is noteworthy that baicalin also increased the expression of ALP and induced the proliferation of DPCs, which may explain its ability to promote the growth of hair follicles, although the exact mechanism by which baicalin promotes ALP expression is unknown.

In summary, the results of the present study indicate that topical administration of baicalin at daily doses of 50 and 100 μmol facilitates the growth of reconstituted hair follicles in mice. The ability of baicalin to activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and increase ALP activity in DPCs in mice likely contributes to the induction of hair follicle growth. It is possible that activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling may be more important than increasing ALP activity in DPCs for baicalin-mediated hair growth, as blocking Wnt/β-catenin signaling with IWR-1 inhibited the effect if baicalin treatment. Therefore, ALP may be induced downstream from Wnt signaling, at least in the context of baicalin-induced Wnt pathway activation and hair growth stimulation. Future studies should extend the observation period to investigate the effects of baicalin on the catagen and telogen phases of the hair cycle and test for any potential adverse events. It may also be of interest to test the effect of baicalin on human dermal and epidermal cells grafted onto immunodeficient mice (31) to determine whether the same effects of baicalin on Wnt/β-catenin signaling and DPC activity are observed in human-derived cells.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81371717 and 81573028). The authors would like to thank Dr Wei-Zheng Wei for his help with this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Lee J, Tumbar T. Hairy tale of signaling in hair follicle development and cycling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:906–916. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos Z, Avci P, Hamblin MR. Drug discovery for alopecia: Gone today, hair tomorrow. Expert Opin Drug Dis. 2015;10:269–292. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang YY, Jiang QE, Li G. The clinical effects of Chinese Medicine Hair Restorer on androgenetic alopecia. Hebei Chinese Med. 2012:1156–1157. In Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moghaddam E, Teoh BT, Sam SS, Lani R, Hassandarvish P, Chik Z, Yueh A, Abubakar S, Zandi K. Baicalin, a metabolite of baicalein with antiviral activity against dengue virus. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5452. doi: 10.1038/srep05452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi H, Chen MC, Pham H, Angst E, King JC, Park J, Brovman EY, Ishiguro H, Harris DM, Reber HA, et al. Baicalein, a component of Scutellaria baicalensis, induces apoptosis by Mcl-1 down-regulation in human pancreatic cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1465–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin SH, Bak S, Kim MK, Sung YK, Kim JC. Baicalin, a flavonoid, affects the activity of human dermal papilla cells and promotes anagen induction in mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2015;388:583–586. doi: 10.1007/s00210-014-1075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu HQ, Fan WX, Zhang H. In vitro effects of baicalin on the growth of human hair follicles and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor by human dermal papilla cells. Chin J Dermatol. 2007;40:416–418. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo AJ, Choi RC, Cheung AW, Chen VP, Xu SL, Dong TT, Chen JJ, Tsim KW. Baicalin, a flavone, induces the differentiation of cultured osteoblasts: An action via the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:27882–27893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohyama M, Zheng Y, Paus R, Stenn KS. The mesenchymal component of hair follicle neogenesis: Background, methods and molecular characterization. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichti U, Anders J, Yuspa SH. Isolation and short-term culture of primary keratinocytes, hair follicle populations and dermal cells from newborn mice and keratinocytes from adult mice for in vitro analysis and for grafting to immunodeficient mice. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:799–810. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehama R, Ishimatsu-Tsuji Y, Iriyama S, Ideta R, Soma T, Yano K, Kawasaki C, Suzuki S, Shirakata Y, Hashimoto K, Kishimoto J. Hair follicle using grafted rodent and human cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2106–2115. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao X, Huang X, Zhou Z, Lin X. An improvement of the 2^(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath. 2013;3:71–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta PS, Folger JK, Rajput SK, Lv L, Yao J, Ireland J, Smith GW. Regulation and regulatory role of WNT signaling in potentiating FSH action during bovine dominant follicle selection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi J, Garza LA. An overview of alopecias. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013615. pii:a013615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirai A, Ikeda J, Kawashima S, Tamaoki T, Kamiya T. KF19418, a new compound for hair growth promotion in vitro and in vivo mouse models. J Dermatol Sci. 2001;25:213–218. doi: 10.1016/S0923-1811(00)00147-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Zhu Y, Sun C, Wang T, Shen Y, Cai W, Sun J, Chi L, Wang H, Song N, et al. Feedback activation of basic fibroblast growth factor signaling via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in skin fibroblasts. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:32. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar SE. WNT signals are required for the initiation of hair follicle development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rishikaysh P, Dev K, Diaz D, Qureshi W, Filip S, Mokry J. Signaling involved in hair follicle morphogenesis and development. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:1647–1670. doi: 10.3390/ijms15011647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider MR, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Paus R. The hair follicle as a dynamic miniorgan. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R132–R142. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang CC, Cotsarelis G. Review of hair follicle dermal cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;57:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Camp JK, Beckers S, Zegers D, Van Hul W. Wnt signaling and the control of human stem cell fate. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2014;10:207–229. doi: 10.1007/s12015-013-9486-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt-Ullrich R, Paus R. Molecular principles of hair follicle induction and morphogenesis. Bioessays. 2005;27:247–261. doi: 10.1002/bies.20184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishimoto J, Burgeson RE, Morgan BA. Wnt signaling maintains the hair-inducing activity of the dermal papilla. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1181–1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, et al. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardy MH. The secret life of the hair follicle. Trends Genet. 1992;8:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90350-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millar SE. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:216–225. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paus R, Cotsarelis G. The biology of hair follicles. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:491–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908123410706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iida M, Ihara S, Matsuzaki T. Hair cycle-dependent changes of alkaline phosphatase activity in the mesenchyme and epithelium in mouse. Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49:185–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Handjiski BK, Eichmüller S, Hofmann U, Czarnetzki BM, Paus R. Alkaline phosphatase activity and localization during the murine hair cycle. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X, Scott L, Jr, Washenik K, Stenn K. Full-thickness skin with mature hair follicles generated from tissue culture expanded human cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:3314–3321. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]