Abstract

Objective

In an effort to refine a model of clinical care identifying effective communication with health care providers (HCPs) as a key skill for successful transition to adult medical care, this study explored the perspectives of emerging adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D) about factors that impact the quality and content of communication with their HCPs.

Methods

Twenty emerging adults with T1D were interviewed about health communication experiences with their pediatric HCP and readiness for transition to adult diabetes care. Interviews were recorded and transcribed; three raters coded transcripts using conventional content analysis for broad themes.

Results

Five themes emerged from the data capturing factors that influence emerging adult-HCP communication: HCP interaction style, HCP consistency, HCP support for autonomy, parental involvement in medical care, and emerging adult comfort with disclosure. Most emerging adults had not discussed transition to adult diabetes care with their HCP; some expressed confidence in their ability to transition while others expressed anxiety about the transition process.

Conclusions

Findings support the conceptual model of communication and inform clinical implications for working with emerging adults with T1D. Continuity of care should be prioritized with transition-age patients. Additionally, HCPs should initiate conversations about engagement in risky behaviors and transition to adult medical care and ensure emerging adults have time without parents to discuss these sensitive topics. Psychologists can enhance the transition process by facilitating effective patient-HCP communication and coaching both patients and HCPs to ask questions about risky behaviors and transition to adult medical care.

Keywords: emerging adults, type 1 diabetes, health communication, transition to adult medical care

Emerging adulthood is a transitional developmental period that typically encompasses ages 18 to 25 and is characterized by changes in educational, vocational, and living situations (Arnett, 2000). For emerging adults with type 1 diabetes (T1D), this period can be especially challenging. In addition to the typical developmental milestones associated with the emerging adulthood period, emerging adults with T1D also assume increasing responsibility for all aspects of T1D care, including daily tasks such as glucose monitoring, carbohydrate counting, and insulin administration, and health care-related tasks such as making health care decisions and scheduling medical visits (Monaghan, Helgeson, & Wiebe, 2015). Emerging adults with T1D may struggle to execute these tasks independently, contributing to higher risk for poor glycemic control and decreased engagement in medical care (Garvey et al., 2013; Hendricks, Monaghan, Soutor, Chen, & Holmes, 2013; Pierce & Wysocki, 2015; Sheehan, While, & Coyne, 2013).

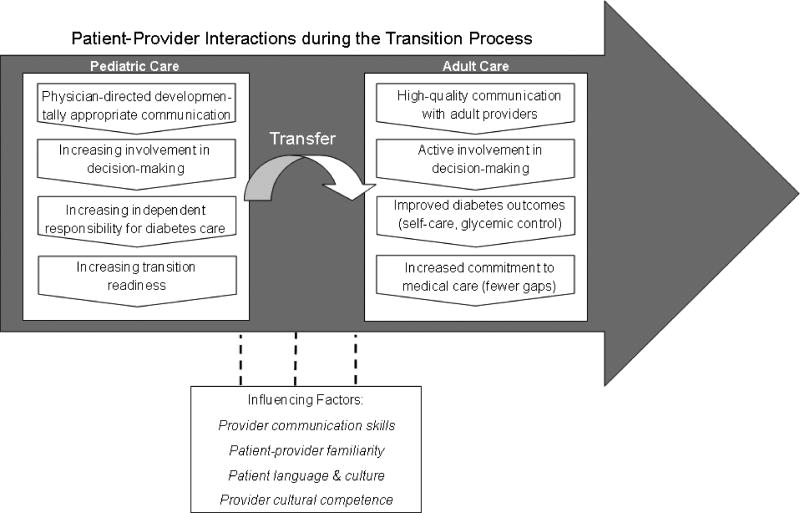

One key aspect of responsibility for T1D care concerns the emerging adult taking a primary role in communicating with health care providers (HCPs) during routine diabetes care. High quality health communication is associated with optimal outcomes for patients with chronic illness (Street, Makoul, Arora, & Epstein, 2009; Zolnierek & DiMatteo, 2009). Further, effective self-advocacy and related health communication skills such as asking questions, disclosing risky behavior, and information sharing are important aspects of T1D self-management that may buffer against some of the challenges experienced during the developmental period of emerging adulthood (Majumder, Cogen, & Monaghan, 2017). Monaghan and colleagues (2013) developed a conceptual model highlighting the role of effective patient-HCP communication in the care of emerging adults with diabetes (see Figure 1). This model was informed by the work of Street and colleagues (2009) linking patient-provider interactions to health care outcomes, and developed to specifically examine the role of communication across the transition to adult medical care. In this model, both emerging adult patients and HCPs have specific tasks around information sharing, promoting autonomy, and engaging in shared decision making for diabetes care while in pediatric care; high-quality communication in these areas may contribute to increased transition readiness and facilitate successful transfer to and engagement in adult medical care (Monaghan, Hilliard, Sweenie, & Riekert, 2013). The concepts in this model can be qualitatively explored to better understand factors that influence the quality of communication between emerging adults and pediatric HCPs prior to the transfer to adult medical care and inform specific, developmentally-targeted strategies to improve health outcomes.

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Emerging Adult-HCP Communication.

From “Transition readiness in adolescents and emerging adults with diabetes: the role of patient-provider communication” by M. Monaghan, M.E. Hilliard, R. Sweenie, & K. Riekert, 2013, Current Diabetes Reports, 13, p. 904. Used with permission from Springer.

There is a growing literature on health care experiences of emerging adults that supports the importance of high quality communication with HCPs. Ritholz and colleagues (2014) completed focus groups with 26 young adults with T1D to examine relationships with HCPs during emerging adulthood. Qualitative results suggested patients desired collaborative communication with HCPs and support for autonomy in medical visits but struggled to achieve this in pediatric care (Ritholz et al., 2014). Other mixed method studies have found that emerging adults and their HCPs do not sufficiently discuss potential changes that occur in adulthood and adult medical care and, as a result, may feel unprepared for adult care (Hilliard et al., 2014; Sheehan, While, & Coyne, 2015). Some evidence suggests patient communication skills may require specific intervention. A recent study with adolescent and young adult patients with irritable bowel disease (IBD) found that disease self-care skills generally improved with age; however, communication with HCPs, including answering and asking questions during medical visits, did not improve (Whitfield, Fredericks, Eder, Shpeen, & Adler, 2015).

Thus, understanding the perspectives of emerging adults regarding factors that influence the quality and content of emerging adult-HCP communication is important to refine models of clinical care for this age group. It is of particular interest to examine health communication prior to the transition to adult medical care, as this study’s guiding conceptual framework (Monaghan et al., 2013) purports foundational experiences and skills gained in pediatric care may facilitate a successful entrance into adult medical care. Pediatric HCPs play an important role in helping emerging adults engage with the health care system and discussions about transition to adult care should begin relatively early in adolescence. Further, advanced skills in health communication are generally expected in adult medical care, as visits tend to focus on the individual patient, may not include family members, and are shorter in duration than pediatric medical visits (Peters, Laffel, & The American Diabetes Association Transitions Working Group, 2011; Pierce & Wysocki, 2015).

The purpose of the current study was to refine a conceptual model of clinical care for emerging adults with T1D (Monaghan et al., 2013), and gain specific insight into their health communication experiences. This qualitative study specifically queried emerging adults about communication with pediatric diabetes HCPs, engagement in diabetes medical visits, and readiness for transition to adult diabetes care. The findings will be used to inform clinical recommendations for emerging adult patients and HCPs working with this population.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants in the present study were recruited from a larger pool of participants enrolled in an ongoing longitudinal study examining patient-HCP communication and related predictors of health outcomes in emerging adults with T1D. Emerging adult participants completed questionnaires at 4 consecutive medical clinic visits and had each medical visit audio recorded to evaluate communication with their HCPs. Inclusion criteria for the larger longitudinal study included: youth between ages 16 – 20 at study enrollment; diagnosed with T1D > 1 year; receiving T1D care from a pediatric HCP; no other significant chronic medical conditions; and English language fluency. For the larger study, 211 recruitment letters were sent; 133 emerging adults were reached and eligible, and 76 emerging adults and a caregiver (if interested) enrolled. The sample was representative of the overall clinic population where the study was conducted.

Enrolled participants were asked to complete an optional qualitative interview regarding health communication experiences in pediatric T1D care. The interview was offered as a rolling invitation as participants completed the fourth and final study visit for the overall longitudinal study, which typically occurred 18 months after study enrollment. The first 23 participants who completed the original study were approached for the interview; 3 declined participation, primarily citing time constraints. Twenty emerging adults agreed and were interviewed. This subsample was representative of the larger sample for the study in terms of key characteristics that may influence communication, including sex, race/ethnicity, T1D duration, and hemoglobin A1c (A1c). Participants who completed the interview received a small incentive ($25 gift card). Coding of the interview data was initiated after the first 12 interviews were completed and continued as new interview data were collected. Qualitative data collection stopped when saturation was reached and it was determined by the two primary coders that obtaining additional interviews would not result in new codes or themes.

Interviews were conducted in person after a diabetes medical visit or over the phone based on participant preference. The study principal investigator or trained research assistants conducted all interviews. Interviewers asked open-ended questions regarding emerging adults’ perspectives on health communication in pediatric care and the transition to adult care. The interview began by eliciting general perceptions about T1D management and their relationship with their diabetes HCP and then asked more specific follow-up questions related to experiences with T1D visits, perceived positive and negative communication experiences with HCPs, and developmental aspects of T1D care (e.g. risky behavior, transition to adult care). The interviews lasted a total of 13.1 minutes (± 5.1; range = 6.7 – 26.0 minutes). Table 1 provides an overview of interview topics. This study was approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Sample Qualitative Interview Questions.

| Interview Questions |

|---|

|

Data Analyses

Twenty interviews were conducted and coded by two primary coders. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim from the audio-recordings. Transcripts were independently reviewed by an additional team member to ensure transcription accuracy. Coders used conventional content analysis to determine broad themes related to emerging adult’s health communication perspectives and experiences (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Content analysis uses an inductive approach to distill conversational content into codes that are then aggregated into categories across interviews. The categories are closely reviewed to organize the individual codes into overarching themes supporting a key construct or idea. The primary coders (KB and MM) independently read the first five transcripts several times to form global impressions of the data, and independently identified key words and phrases to create initial codes and develop codebooks. They then met, compared codebooks, discussed and jointly defined all codes, and reviewed each others’ coding. Coding discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, from these two codebooks, a shared codebook was created. This shared codebook was used to independently code the remaining transcripts, with ongoing meetings to revise the codebook based on new codes. Codes were grouped into themes based on content. No new meaningful information was derived from final 4 interviews, suggesting that data saturation was met. The primary coding was completed without access to qualitative software. After two independent coders finished coding all 20 transcripts, a third coder independently coded a subset of transcripts (25%) using Atlas.ti. This reliability check ensured that the codebook generated by the two primary coders was complete; there were no discrepancies in the overall thematic content derived from the subset of transcripts.

Results

Demographics

Participants were 20 emerging adults (mean age = 18.8 ± 1.5 years) who had been diagnosed with T1D for an average of 9.6 years (±3.6 years). The mean hemoglobin A1c (A1c) of the sample was 8.5%, which is above the recommended A1c level for youth (A1c < 7.5%; American Diabetes Association, 2017). Participants represented experiences with eight HCPs (88% female), including 6 pediatric endocrinologists/diabetologists and 2 nurse practitioners. At the time of the interview, 19 out of 20 participants (95%) were receiving T1D care at a pediatric center. Although 1 participant had recently transferred to adult medical care when the interview was conducted, the interview questions focused on health communication experiences with the participant’s pediatric HCP. See Table 2 for additional demographic information.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Emerging Adult Sample.

| % | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% female) | 70 | -- | -- | -- |

| Age (years) | -- | 18.8 | 1.5 | 16.9–21.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| % Non-Hispanic white | 65 | |||

| % African American/black | 15 | |||

| % Hispanic | 15 | |||

| % Other | 5 | |||

| Living situation (% living at home with parent) | 70 | -- | -- | -- |

| Education | ||||

| % Enrolled in high school | 45 | |||

| % Enrolled in 2 or 4 yr college | 35 | |||

| % Not enrolled in school | 20 | |||

| Disease duration (years) | -- | 9.6 | 3.6 | 3.4–19.1 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | -- | 8.5 | 1.7 | 6.7–13.7 |

| Insulin regimen (% using pump) | 45 | -- | -- | -- |

Factors Influencing Patient-HCP Communication

Five major themes emerged related to HCP interaction style, HCP consistency, HCP support for autonomy, parental involvement in medical care, and emerging adult comfort with disclosure. These themes are discussed below and in Table 3. As guided by the model of patient-provider communication in emerging adulthood (Monaghan et al., 2013), an additional theme queried in this sample related to perceived readiness to transition to adult medical care.

Table 3.

Representative Themes and Quotes.

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

1. HCP interaction style:

|

“She cares about her patients on a personal level.” |

| “She definitely does listen to me; t’s refreshing to have a physician who cares that much.” | |

| “She’s very straightforward. She doesn’t fool around, she just tells you what you need to do.” | |

| “I like the bluntness and the openness that she provides.” | |

| “I don’t like the way the visits go now because I’m not doing well.” | |

2. HCP Consistency:

|

“The fact that she recognizes me when I walk into the clinic, or remembers something I said in my last appointment, is nice to know that she actually knows who I am as a human being, and I think that’s really important.” |

| “I’ve had no feelings toward all of them except for one, my first one, and I despised her…[My HCP is] going to leave anyway, or I’m going to leave before she leaves.” | |

3. Support for autonomy:

|

“She gives me more options about how to treat things. I have more input.” |

| “She always asks me if I disagree or agree with any changes that she’s making.” | |

| “She’ll ask me first, and then if I don’t know the answer to something we’ll go over to my parents.” | |

| “She’s always directed and looking at me.” | |

4. Parental involvement in medical care:

|

“They’re less involved but they’re still concerned. They’ll ask how the doctor’s appointment was and what we talked about, but in a very respectful manner. They’re not overbearing in the information that they want me to provide to them.” |

| “I think the last time my mom asked a question, and I was like “I could have told you the answer to that” and I talked about that with her, so today they didn’t really ask any questions.” | |

| “When my mom went in with me, she would talk over me and take over the whole appointment.” | |

5. Emerging adult comfort with disclosure:

|

“I feel much more comfortable talking to her about pretty much anything; like ‘hey, I’m having a problem with this, and it’s kind of personal and embarrassing, but it’s an issue.’” |

| “I’m always forthcoming with her about risky behavior – if I’m putting something into my body, I want to know what it’s going to do to my diabetes.” |

HCP Interaction Style

A number of codes reflected personal qualities that emerging adults reported valuing in their HCPs; commonly reported and highly valued qualities of HCPs included warmth, positivity, consistent support, and a blunt or straightforward approach to delivering information. Seventeen participants specifically reported desiring an HCP who was warm, positive, and engaging. These qualities led to a close relationship with the HCP that evolved and deepened with time, particularly as the emerging adult started to take on more responsibility for aspects of daily T1D management. For example, one emerging adult said, “She’s very friendly and warm and I’m comfortable with her because of that. I’ve met with many doctors who are stiff, and cold, and strange.” This warmth was also evident by the HCP taking an interest in the emerging adult’s life outside of T1D. As one participant noted, “[My HCP] knows the things I might be going through in life and always remembers to ask me.”

Nine participants felt consistency in warmth and positivity was important, particularly when they were not meeting T1D goals. For example, one emerging adult stated, “[My HCP] allows you to make errors, and helps when you make errors, but she is never going to yell at you.” Another noted, “If I’m not meeting [my goals], then she says what we can do to meet them. But she’s not mean about it.” This desire for warmth from their HCPs was balanced with a preference for blunt delivery of information or recommendations. One participant said, “[My HCP] doesn’t sugar coat anything, which is really nice. It’s very upfront, and I think that’s what a lot of people need to hear.” Six participants perceived a decrease in warmth when glycemic control was poor. One participant noted, “When I’m meeting my goals, it’s a happier visit. When I’m not meeting my goals, the energy in the room is really negative.” Another participant discussed the challenges of persistent poor glycemic control when the HCP judges without offering any solutions. “I don’t like the appointments because they all just sit there and say ‘this isn’t good, and that isn’t good, and you need to be better,’ and I’m just like, ‘I know this’.”

HCP Consistency

Emerging adults valued the opportunity to develop a relationship with their HCP over time. Fourteen participants had seen the same HCP throughout adolescence and into emerging adulthood, and this familiarity contributed to a more in-depth relationship. For example, one participant noted, “We’ve built a good relationship so it’s going to be sad when I have to leave. [My HCP] knows me.” Another commented, “I feel like just naturally from being her patient longer, she knows me better.” Six out of the 20 participants had changed HCPs in recent years. For 3 of these participants, the change of HCP was a negative event. One participant reported having a number of different HCPs since she was diagnosed, resulting in low overall satisfaction with her T1D care. “I’ve had at least 6 doctors, because [this hospital] has a terrible diabetic program. I can already figure that out.” Another expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of personal interaction with a new HCP: “I felt like I was just another number in her office.” However, others reported this as a neutral or positive event. One participant specifically noted, “Before [current HCP], I had another doctor who was boring and depressing.” HCP Support for Autonomy. Emerging adults reported a strong desire to serve as primary diabetes managers and generally favorably viewed HCP support for increasing independence. Nine participants noticed HCPs tried to increase autonomy by directing conversations and eye contact towards the emerging adult rather than a parent. One reported that, now as an emerging adult, “[My HCP] asks me first and then if I don’t know something, we’ll go over to my parents.” Time alone with an HCP led to more emerging adult-HCP communication. Another participant noted, “I speak up more in appointments because it’s just me in the room, whereas before my mom said more in my appointments.” Support for autonomy also was evident through greater engagement in shared decision making processes integral to diabetes care. According to one emerging adult, “[My HCP will] ask ‘how do you feel about this?’ or ‘why do you think this is like this?’ and [will] include me in the treatment of myself.” Participants noted that this opportunity for insight into not just what decisions are made but how decisions are made was an important part of developmental process of autonomy in diabetes care.

Parental Involvement in Medical Care

In addition to HCPs supporting autonomy in medical care, 18 participants reported that their parents decreased involvement in T1D-related communication during emerging adulthood. This was typically favored by emerging adults, and they valued when parents gradually reduced involvement in medical care while remaining supportive. One participate explicitly stated that taking more initiative for health communication was an impetus for taking on more responsibility in overall T1D care: “I think that little bit of independence has changed how I approach my diabetes management – it’s me, not my mother, taking care of me.” Although most participants felt that they were able to assume increasing independence in T1D visits, some had difficulty achieving this if a parent was used to dominating the relationship with the HCP. Six participants noted that they had to directly ask their parents to decrease their involvement in medical care and health communication. One participant noted, “I’ve become more forceful in making it understood that I’m going to see my doctors by myself.” Another asked her dad to participate less in visits, stating, “My dad is a big mouth and wants to keep saying stuff, and he would just talk too much.” Emerging Adult Comfort with Disclosure. A key component of T1D-related communication in emerging adulthood is the ability to disclose risky behavior (e.g. substance use, sexual risk behavior) and ask related questions. This topic was directly queried with this sample. Fifteen participants reported general comfort related to discussing risky behaviors. Four participants reported asking questions related to risky behaviors, particularly if they did not perceive any judgment associated with risky behaviors; the other participants had not yet raised questions about risky behavior but felt as if they could in future visits if needed. One participant shared, “I’m never scared to be honest with my doctor,” while another noted, “I feel very comfortable asking questions. There’s never any judgment.” However, 3 participants noted comfort with disclosure of information related to risky behaviors but not with initiating questions about it. Rather, they preferred that their HCPs initiated the topics and they then felt comfortable answering questions honestly. For example, one emerging adult expressed some hesitation but stated, “If it was really uncomfortable and I needed to ask a question, I could.” Another noted that his parent typically raised risky behavior but he did not. “My mom normally brings up that [drinking], because she worries about it and wants [my HCP’s] opinion. I probably wouldn’t bring up that kind of stuff.” Another emerging adult reported that disclosure would depend on the HCP, as he would feel comfortable with his current HCP but not his prior one. A negative bias toward engagement in risky behavior prevented disclosure for two participants. One participant shared an experience discussing alcohol use with her HCP. “[My HCP] told me ‘I shouldn’t be [drinking alcohol],’ but I knew I was going to do it anyway and I wanted to know how to keep myself safe. I ended up just looking around the internet…” Another reported using the internet to find information about marijuana use and T1D rather than talking with her HCP.

Readiness for Transition to Adult Medical Care

Successful transfer to adult medical care is the outcome of the conceptual model guiding this study. Thus, the interview queried emerging adults on their feelings of readiness to transition care to an adult diabetes HCP. Fifty-five percent of participants (M age = 18.72 years) reported they had not yet discussed transition to adult medical care or when the transfer of care may occur. Although transition was not directly discussed, some participants felt comfortable with the idea of moving to adult care and taking on increasing responsibility for all T1D related tasks. One participant noted, “I haven’t talked about it with [HCP]… As long as I find somebody who helps me with what I need, I think I should be pretty good.” Another stated, “I feel very comfortable and that I’ve been given all the tools I really need. It’s going to be up to me to implement them myself.” However, 5 participants expressed anxiety and avoidance of the topic, sharing “I want to stay here forever. [Moving on] is not in my plans yet. I haven’t thought about it or talked about it – I’ll deal with it when I have to,” and, “I don’t know how to do all that [handing insurance, ordering medical supplies, etc.] but I can’t imagine it would be that hard to learn.” When asked about resources for preparation for adult T1D care, 11 participants identified a personalized recommendation for an adult care provider as the most helpful resource. “I want recommendations…for someone who would be a good fit for me.” Three participants also requested a developmentally-specific education group focused on topics associated with young adulthood and diabetes that were not likely to be discussed in other classes, such as pregnancy and reproductive health. Health insurance resources in young adulthood were also mentioned.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore perceived factors influencing health communication in emerging adults with T1D during this transitional developmental period. The qualitative interview was designed to capture emerging adult perspectives and inform strategies HCPs can utilize with this population. The study was guided by a model of emerging adult-HCP interaction that focused on building communication skills in pediatric care as a way to prepare for a successful transfer to adult medical care. Study findings support the guiding conceptual framework and provide insight into emerging adults’ perceptions of health communication.

HCP communication skills are a key contextual factor in the guiding conceptual framework. The qualitative interviews reveal the interaction styles that emerging adults prefer, and these styles may promote the development of skills associated with transition readiness, such as engagement in shared decision making. Emerging adults desired friendly, supportive interactions with their HCPs and most participants preferred to be treated like an adult while in pediatric care. HCPs should aim to maintain this warm and collaborative interaction style even when diabetes goals are not being met. These preferred characteristics are emblematic of patient-centered care, a theoretical frame that supports the delivery of effective health care through relationships characterized by warmth, support, trust, patient activation and engagement, and opportunities for shared decision making (Levinson, Lesser, & Epstein, 2010). Recent research found that patient-centered adolescent primary care was associated with greater likelihood to have a confidential conversation and more frequent discussions of health behaviors such as sexual health or substance use, suggesting patient-centered care can optimize patient-HCP communication (Toomey et al., 2016). Although patient-centered care has been less studied with emerging adults with chronic illness, the themes derived from interview data with the current sample support the importance of the provision of patient-centered care to promote high quality health communication between emerging adults and pediatric HCPs.

Another key facilitator was patient-HCP familiarity, and emerging adults benefited from consistency in relationships with their HCP. Thus, continuity of care should be prioritized when working with this age group. Interpersonal continuity of HCPs is associated with better patient-reported HCP communication and engagement in care (Love, Mainous, Talbert, & Hager, 2000), and, for emerging adults with T1D, HCP continuity has been associated with reduced risk of hospitalization (Nakhla, Daneman, To, Paradis, & Guttmann, 2009). Thirty percent of our sample saw multiple HCPs over the 18-month span of the larger study and, for some, it was as a negative experience. While this may be an unavoidable aspect of coordinating appointments within a large clinic, it poses challenges to emerging adults preparing for transition. On one hand, emerging adults must convey all relevant information that may not be explicitly listed in the medical chart to new HCPs, and this could lead to miscommunication or decreased disclosure during the medical visit. On the other hand, adapting to new HCPs is a skill of adulthood, and transition to adult care in particular, so HCPs and psychologists could utilize strategies to help emerging adults adapt to different HCP communication styles and practice self-advocacy skills.

Similar to other literature and as indicated in the guiding conceptual model, emerging adults in this sample appreciated developmentally appropriate interactions in pediatric care, such as being treated as the primary decision maker and not downplaying difficult conversations (Hilliard et al., 2014). They also valued when parents naturally decreased their involvement in medical visits. However, challenges remain related to disclosure of risky behavior and some emerging adults preferred HCPs to initiate these conversations. While many participants said they would be comfortable asking questions about risky behavior, only 4 participants had asked direct questions related to this topic. Pediatric HCPs should take the lead to provide information about risky behaviors and check in frequently, and without judgment, to see if there are concerns that should be discussed. It is important for HCPs to offer time without parents in the room to discuss these sensitive topics. Existing research has demonstrated time alone with HCPs results in increased discussion of sensitive health topics (Gilbert, Rickert, & Aalsma, 2014), and the current study found that some emerging adults had to advocate for this important time alone. Comfort with disclosure is a crucial skill for adult medical care, and HCPs and related health professionals like psychologists are in a unique position to facilitate these skills in pediatric care. In this sample, over half of emerging adults of transition age had not yet discussed adult T1D care with their HCPs. Some emerging adults felt confident in their ability to transition while others did not; this ambivalence is common among a transition-aged population (Garvey et al., 2013; Tuchman, Slap, & Britto, 2008). When asked about desired resources for transition, participants requested their HCPs provide personalized recommendations and extended support throughout the transition. The request for a tailored HCP recommendation is common among youth with T1D and highlights the value placed on a pediatric HCP knowing them as a patient (Garvey et al., 2012; Ritholz et al., 2014). HCPs may not have the resources to provide specific recommendations to all emerging adult patients. However, HCPs should strive to meet this need by engaging in frequent discussions about preparing for adult medical care and providing general recommendations and guidance to all emerging adult patients, even if they can’t provide individualized recommendations. Future research should examine if the quality of emerging adult-HCP communication is associated with increased discussion of transition-specific topics.

There are several strengths of this study. The current sample includes emerging adults spanning the transitional age range of 17–21 at time of interview completion, capturing unique experiences of high school and college-aged youth. The study was guided by a conceptual framework of emerging adult-HCP communication, and this model was largely supported by themes that emerged from these analyses. However, this study also has some limitations. The current sample represents the experiences of emerging adults within one pediatric center. This practice allows patients to stay in pediatric T1D care until completion of college (~age 22), so some youth in this sample may not transfer to adult care for 3 to 4 more years. Additionally, health communication is a dynamic interaction between the patient and the HCP and potentially a parent, and future research should include HCP or parent perspectives of factors that influence patient-provider communication. It also will be important to expand this research with young adults who have transferred to adult medical care to reflect on how communication with pediatric HCPs contributed to the completed transition process. Questions in the interview guide were guided by literature and a theoretical model with an a priori interest in communication. Thus, the themes derived from these analyses represent emerging adult perspectives on communication but, if asked more broadly, recommendations related to areas other than communication may have been raised as part of their overall satisfaction with diabetes care. Lastly, although the current sample is ethnically diverse, emerging adults were predominantly female and most were enrolled in either high school or college courses. HCPs in this sample were largely female as well. The guiding model hypothesized patient language and culture and HCP cultural competence as key contextual factors for communication, yet these themes did not emerge in this sample. As such, these findings may not generalize to a more representative population of emerging adults or HCPs, and should be replicated in larger samples to provide deeper insight into the health communication experiences of emerging adults with T1D.

The themes identified in this study provide a number of avenues to improve patient-HCP communication in pediatric care. Psychologists play a key role in developing self-advocacy skills in youth with chronic illness and can facilitate high-quality patient centered communication among patients and diabetes HCPs. Attention to patient communication skills during assessments of transition readiness or plans to address transition-related skills may increase patient engagement in and preparation for independent medical visits. Encouraging patients to ask questions and engage in shared decision making opportunities also can promote autonomy. Further, establishing developmentally-appropriate clinic procedures such as continuity of HCPs and ensuring emerging adults have time alone in medical visits can promote open discussion about T1D management and best prepare youth for adulthood and adult medical care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant number K23DK099250) to MM.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(Suppl 1):S1–S135. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey KC, Finkelstein JA, Laffel LM, Ochoa V, Wolfsdorf JI, Rhodes ET. Transition experiences and health care utilization among young adults with type 1 diabetes. Patient Preference & Adherence. 2013;7:761–769. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S45823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey KC, Wolpert HA, Rhodes ET, Laffel LM, Kleinman K, Beste MG, Finkelstein JA. Health care transition in patients with type 1 diabetes: Young adult experiences and relationship to glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(8):1716–1722. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert AL, Rickert VI, Aalsma MC. Clinical conversations about health: The impact of confidentiality in preventive adolescent care. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55(5):672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks M, Monaghan M, Soutor S, Chen R, Holmes CS. A profile of self-care behaviors in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 2013;39(2):195–203. doi: 10.1177/0145721713475840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard ME, Perlus JG, Clark LM, Haynie DL, Plotnick LP, Guttmann-Bauman I, Iannotti RJ. Perspectives from before and after the pediatric to adult care transition: A mixed-methods study in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(2):346–354. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson W, Lesser C, Epstein R. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(7):1310–1318. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MM, Mainous AG, Talbert JC, Hager GL. Continuity of care and the physician-patient relationship: The importance of continuity for adult patients with asthma. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(11):998–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder E, Cogen FR, Monaghan M. Self-management strategies in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2017;31(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan M, Helgeson V, Wiebe D. Type 1 diabetes in young adulthood. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2015;11(4):239–250. doi: 10.2174/1573399811666150421114957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan M, Hilliard M, Sweenie R, Riekert K. Transition readiness in adolescents and emerging adults with diabetes: the role of patient-provider communication. Current Diabetes Reports. 2013;13(6):900–908. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0420-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakhla M, Daneman D, To T, Paradis G, Guttmann A. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: Findings from a universal health care system. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1134–e1141. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Laffel L The American Diabetes Association Transitions Working Group. Diabetes care for emerging adults: Recommendations for transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care systems. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11) doi: 10.2337/dc11-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JS, Wysocki T. Topical review: Advancing research on the transition to adult care for type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015;40(10):1041–1047. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritholz MD, Wolpert H, Beste M, Atakov-Castillo A, Luff D, Garvey KC. Patient-provider relationships across the transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care: A qualitative study. Diabetes Educator. 2014;40(1):40–47. doi: 10.1177/0145721713513177. doi:0.1177/0145721713513177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan AM, While AE, Coyne I. The experiences and impact of transition from child to adult healthcare services for young people with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetic Medicine. 2015;32(4):440–458. doi: 10.1111/dme.12639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street RL, Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009;74(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey S, Elliott M, Schwebel D, Tortolero S, Cuccaro P, Davies S, Schuster M. Relationship between adolescent report of patient-centered care and of quality of primary care. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(8):770–776. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman LK, Slap GB, Britto MT. Transition to adult care: Experiences and expectations of adolescents with a chronic illness. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008;34(5):557–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield EP, Fredericks EM, Eder SJ, Shpeen BH, Adler J. Transition readiness in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A patient survey of self-management skills. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2015;60(1):36–41. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence: A meta-analysis. Medical Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]