Abstract

Although laboratory procedures are designed to produce specific emotions, participants often experience mixed emotions (i.e., target and non-target emotions). We examined non-target emotions in patients with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), other neurodegenerative diseases, and healthy controls. Participants watched film clips designed to produce three target emotions. Subjective experience of non-target emotions was assessed and emotional facial expressions were coded. Compared to patients with other neurodegenerative diseases and healthy controls, FTD patients reported more positive and negative non-target emotions, whereas AD patients reported more positive non-target emotions. There were no group differences in facial expressions of non-target emotions. We interpret these findings as reflecting deficits in processing interoceptive and contextual information resulting from neurodegeneration in brain regions critical for creating subjective emotional experience.

INTRODUCTION

In emotion research, stimuli such as film clips, pictures, or situational challenges are presented to participants to induce a particular target emotion [1–3]. In reality, most stimuli produce a mix of target and non-target emotions (e.g., a disgusting film may elicit disgust and amusement). Previous research has typically focused on target emotions, whereas non-target emotions are often overlooked.

Subjective Experiences of Emotions

There are several models of how subjective emotional experience arises [4–6]. In “peripheralist” views [5,7*,8*,9], subjective emotional experience is derived from interoceptive information produced by the physiological activity that accompanies emotion (e.g., changes in facial expressions and autonomic responses). Neuroimaging studies suggest that these processes are supported by the anterior insula, amygdala, ventral striatum, anterior temporal lobes, and medial prefrontal cortices [7*]. Therefore, disruptions in any of these brain regions may result in altered subjective experiences of emotions [10**–13].

Experiencing non-target emotions in situations that predominantly elicit strong target emotions may reflect alterations in emotion processing. For example, patients with schizophrenia report more negative non-target emotions in response to positively-valenced stimuli, which has been linked to deficits in emotional memory and an inability to overcome prepotent response tendencies [14,15]. From a functional perspective, increased subjective experience of non-target emotions may interfere with adaptive learning and social communication [5,16]. For instance, experiencing enjoyment when confronted with contaminated food increases health-harming approach behaviors. Similarly, experiencing happiness when a loved one is grieving may lead to socially inappropriate responses, which can impair relationship quality.

Emotional functioning in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are two common forms of dementia characterized by distinct patterns of neurodegeneration. In FTD, neurodegeneration primarily occurs in the lateral and medial frontal lobes, anterior temporal lobes, cingulate cortex, ventral striatum, and insula [17*], areas thought to be critical for the generation of emotion and the processing of interoceptive information [7*,12]. In AD, neurodegeneration occurs in the medial temporal lobes, including the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, areas critical for memory [17*]. In later stages of AD, limbic regions (e.g., amygdala) and other cortical regions (e.g., lateral temporoparietal cortex) are also affected [17*–20].

Alterations in subjective emotional experience are often seen in patients with FTD and AD [21**,22]. For example, patients with FTD experience less disgust and embarrassment in response to disgusting film clips and embarrassing situations [10**,23,24]. Patients with AD report greater emotional distress when exposed to the negative emotions of others [25]. Studies of subjective emotional experience in FTD and AD patients have overwhelmingly focused on target emotions. In this study, we aim to provide a comprehensive assessment of subjective experience of non-target emotions.

The present study

The present study examined subjective experience of non-target emotions in patients with FTD, AD, and two control groups (patients with other neurodegenerative diseases, and neurologically-healthy controls) in response to emotional film clips selected to induce amusement, sadness, and disgust. We also examined facial expressions in response to the film clips to determine whether alterations in non-target emotions were limited to subjective experience or were also found in other aspects of emotion responding. We hypothesized that patients with FTD and AD would have altered subjective experience of non-target emotions relative to both control groups.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included: (a) 99 patients with FTD; (b) 45 patients with AD; (c) 45 neurodegenerative controls (NC) -- patients with neurodegenerative diseases that primarily affect motor but not emotional functioning (e.g., corticobasal syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis without symptoms of frontotemporal degeneration); and (d) 37 healthy controls (HC); Table 1. Dementia severity was assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of the boxes [26]. Including the NC group enabled us to rule out the possibility that found changes in non-target emotions in FTD and AD patients are also common in other neurodegenerative diseases. Details concerning participant recruitment and patient diagnosis can be found in Verstaen et al. [10**].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and patient functioning.

| FTD | AD | NC | HC | Between-group comparisons

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/χ2 | Post hoc tests | |||||

| n | 99 | 45 | 45 | 37 | ||

| Sex | 59 M; 40 F | 23 M; 22 F | 23 M; 22 F | 15 M; 22 F | 4.16 | |

| Age | 63.32(0.77) | 62.18(1.35) | 67.33(1.15) | 67.19(1.33) | 5.22*** | FTD<NC*, FTD<HC†, AD<NC*, AD< HC* |

| Dementia Severitya | 5.05(0.34) | 4.27(0.32) | 4.48(0.46) | 0.00(0) | 30.39*** | FTD>HC***, AD>HC***, NC>HC*** |

| Emotion Rating Deficit | 0.27(0.03) | 0.22(0.04) | 0.21(0.04) | 0.19(0.04) | 0.91 | |

Dementia severity was assessed by Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. FTD = Frontotemporal dementia; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; NC = Neurodegenerative control; HC = Healthy control; F = Female; M = Male. Mean (SEM).

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Procedure

Participants watched three film clips in a fixed order that were selected to induce amusement (I Love Lucy), sadness (The Champ), and disgust (Fear Factor). Previous research has demonstrated that these film clips elicit strong target emotions in healthy adults [2,10**,24,27,28]. Emotional facial expressions were recorded continuously using partially hidden cameras. After each film clip, participants were asked: (a) an open-ended question where they indicated the emotion they felt most strongly when watching the film; (b) a valence question, where they rated the valence of their overall experience while watching the film (i.e., “good,” “neutral,” or “bad”); and (c) ten specific emotion questions where they rated their subjective experience of ten different positive and negative emotions (i.e., affection, fear, amusement, anger, shame, disgust, embarrassment, enthusiasm, pride, sadness) during the film clips on a three-point scale (0=not at all; 1=a little; 2=a lot).

Measures

Subjective Emotional Experience

Target emotions for the three emotion-eliciting film clips were amusement, sadness, and disgust. Non-target emotions were the other nine emotions reported on the rating scales after each film clip (Figure 1A–C left). In the analyses, we grouped positive and negative non-target emotions separately to capture changes in subjective emotional experiences by valence (Figure 2A). Aggregating emotions resulted in three emotion categories (i.e., positive non-target, negative non-target, and target), which also helped us control for Type I error by reducing the number of statistical tests.

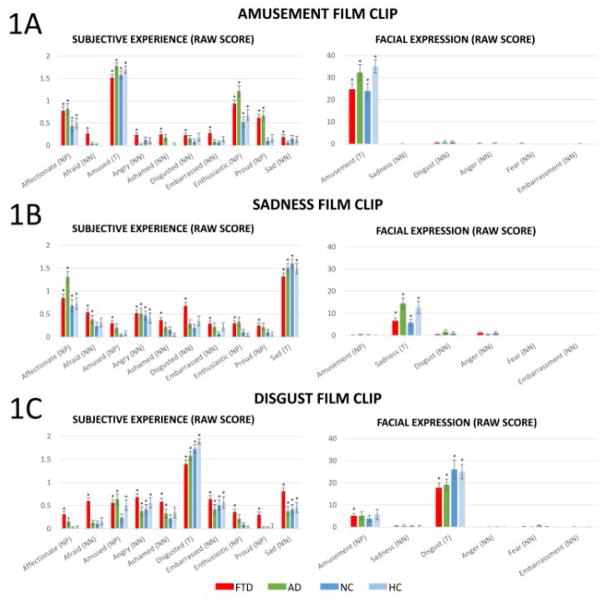

Figure 1.

Raw scores of subjective experience of 10 emotions (left) and facial expressions of six emotions (right) in response to the amusement, sadness, and disgust film clips. M ± 1 SEM; T = Target emotion; NP = Positive non-target emotions; NN = Negative non-target emotions. The annotation * indicates the mean response of the group was significantly different from zero at the level of p<.05.

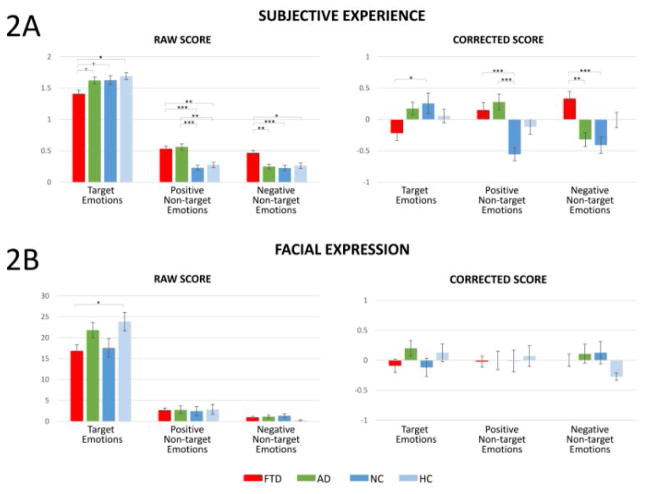

Figure 2.

Averaged subjective experience (2A) and facial expressions (2B) of emotions across film clips by emotion categories as indexed by raw (left) and corrected (right) scores. Annotations indicate significant or trending between-group differences. M ± 1 SEM. †p<.10; *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Emotional Facial Expression

Facial expressions of happiness/amusement, sadness, disgust, anger, fear, and embarrassment (Figure 1A–C right) during a pre-selected 30s “hot spot” (i.e., the segment of maximal emotional impact as judged by an independent panel of viewers) for each film were coded by trained research assistants using the Expressive Emotional Behavior (EEB) Coding System [29] (Cronbach’s alpha=.91). See Verstaen et al. [10**] for details on the coding procedure. Scores for facial expressions of target, positive non-target, and negative non-target emotions were calculated by averaging facial expressions in their respective categories1.

Emotion Rating Deficit

Self-report of emotional experiences can be impacted by language impairments [24] and/or the inability to rate emotions on scales. To quantify these deficits, we examined inconsistencies between the valence of participants’ answers to the open-ended questions and the valence they endorsed in the subsequent question. For example, if the participant reported “I felt sad” but then reported the valence of this emotion to be “good”, this suggested that the participant was unable to: (a) understand the meaning of “sadness”, and/or (b) rate their emotional experience on the scale. The average number of inconsistencies was calculated for each participant to index emotion rating deficits.

Data Pre-processing

In addition to “emotion rating deficits”, subjective emotional experience in patients with neurodegenerative disease can be affected by many other factors including dementia severity, age, and sex [28,30,31]. In addition, individuals who experience higher levels of target emotions may be more likely to report experiencing higher levels of non-target emotions and vice versa due to individual differences in emotional experience [32]. We computed corrected scores of subjective emotional experiences2 where the above factors3 were accounted for (i.e., self-reported target [or non-target] emotions were accounted for in the corrected scores of non-target [or target] emotions). Similarly, we computed corrected scores of facial expressions of target and non-target emotions accounting for dementia severity, age, sex, and facial expressions of non-target (or target) emotions.

Data Reduction

In preliminary data analyses, for subjective experience and facial expression of positive and negative non-target emotions, we performed a repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVA; 3 film clips4 x 4 diagnoses) of the corrected scores. These analyses did not reveal any significant main effects of film clip, nor any interaction effects between film clip and diagnosis, Fs<1.52, ps>.16. Thus, we averaged the data across the three film clips, which reduced the number of non-target emotion variables to four: (a) subjective experience of positive non-target emotions, (b) subjective experience of negative non-target emotions, (c) facial expressions of positive non-target emotions, and (d) facial expressions of negative non-target emotions5. For consistency, we also averaged the data across the three film clips for the target emotion measures6, which resulted in two variables: (e) subjective experience of target emotions, and (f) facial expression of target emotions.

RESULTS

Subjective Emotional Experience

Figure 1A–C left shows participants’ subjective experience of ten emotions for the three film clips (raw score M ± 1 SEM; emotions are listed in the same order as presented to participants7). One-sample t-tests (test value = 0; Bonferroni corrected for 40 comparisons in each film clip) revealed that participants across diagnostic groups reported experiencing a range of emotions that included both target emotions (which serve as a manipulation check indicating our stimuli successfully elicited target emotions) and non-target emotions at levels that significantly differed from zero (ps<.05).

Figure 2A shows averaged subjective emotional experiences by emotion categories based on raw and corrected scores. ANOVAs of the corrected scores revealed a significant diagnosis main effect for target, F(3, 215)=3.45, p=.018, positive non-target, F(3, 215)=7.40, p<.001, and negative non-target emotions, F(3, 215)=8.86, p<.001. Post-hoc comparisons (Bonferroni corrected) revealed that FTD patients reported fewer target emotions and more positive and negative non-target emotions than NC (ps<.05), and more negative non-target emotions than AD patients (p=.001). AD patients reported more positive non-target emotions than NC (p<.001). To examine the robustness of these effects, we performed the same analyses on raw scores of subjective emotional experiences and found similar results with significant main effects of diagnosis across all three emotion categories, Fs(3, 215)>4.71, ps<.003. Differences between HC and FTD patients in all emotion categories, and between HC and AD patients in non-target positive emotions were statistically significant when examining raw scores (ps<.014) but not corrected scores. This may be because corrected scores accounted for dementia severity, which attenuated effects between FTD/AD patients and healthy controls (all HC had a dementia severity score of zero, Table 1).

Facial Expressions

Figure 1A–C right shows participants’ facial expressions of six emotions for the three film clips (raw score M±1 SEM). One-sample t-tests (test value = 0; Bonferroni corrected for 24 comparisons in each film clip) revealed that participants across diagnostic groups expressed target emotions in all film clips at levels that significantly differed from zero (ps<.05). Participants did not express non-target emotions in all film clips except the FTD patients expressed amusement (significantly greater than zero) in the disgust film clip (p<.05).

Figure 2B shows averaged responses by emotion categories based on raw and corrected facial expression scores. ANOVAs of the corrected facial expression scores did not reveal any significant diagnosis main effects across all emotion categories: target, F(3, 219)=1.20, p=.31; positive non-target, F(3, 218)=0.13, p=.94; negative non-target, F(3, 219)=1.39, p=.25. We also analyzed raw facial expression scores and found similar results in non-target emotions, Fs<1.44, ps>.23. However, a significant diagnosis main effect was found for target emotions, F(3, 220)=2.96, p=.03. Bonferroni-corrected comparisons revealed that FTD patients exhibited fewer target facial expressions than HC at trend level (p=.059).

Pearson correlations (on corrected scores) were conducted to examine whether participants’ subjective experience of emotions was associated with facial expressions they expressed within each emotion category. Among all participants, significant correlations were found between facial expressions and subjective experiences for target emotions, r=.20, p=.003, but not for positive non-target, r=−.01, p=.86, or negative non-target emotions, r=−.05, p=.46. Similarly, within each diagnostic group, no significant correlations were found between subjective experience and facial expression of non-target emotions, rs<.22, ps>.15. These results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between subjective experience and facial expression of emotions.

| Pearson correlations between subjective experience and facial expression of emotions

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Target emotions | Positive Non- target emotions | Negative Non- target emotions | |

| All groups combined by diagnostic group | .20** | −0.01 | −0.05 |

| FTD | .22* | −0.12 | −0.08 |

| AD | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| NC | 0.29† | 0.22 | −0.07 |

| HC | 0.11 | −0.09 | −0.15 |

FTD = Frontotemporal dementia; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; NC = Neurodegenerative control; HC = Healthy control

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01.

DISCUSSION

Results revealed that participants across all diagnostic groups reported experiencing a range of emotions that included both target emotions and non-target emotions at levels that significantly differed from zero. We also found that patients with FTD and AD tended to experience more “mixed emotions” when watching emotionally arousing film clips. Indeed, when compared to control groups, patients with FTD reported experiencing more positive and negative non-target emotions, while patients with AD reported experiencing more positive non-target emotions. These effects were specific to patients with FTD and AD and did not generalize to other neurodegenerative diseases. These effects generalized across three different film clips and were specific to subjective emotional experiences; patients with FTD and AD did not display more facial expressions of non-target emotions when compared to the control groups.

Sources of Altered Subjective Emotional Experience

According to peripheralist views, subjective emotional experience arises from the individual’s processing of interoceptive information, which primarily results from “proprioception” (derived from the action of the somatic nervous system; e.g., facial expressions, changes in posture) and “visceral perception” (derived from the action of the autonomic nervous system; e.g., cardiovascular and electrodermal activity) of bodily changes that occur in emotions [5,7*,8*,9]. Thus, increased experience of non-target emotions in FTD and AD patients might result from alterations in: (a) somatic and/or autonomic emotional responding, and/or (b) production and processing (e.g., interpretation) of interoceptive information. Social constructivist views [4,6,33] would add to these the possibility of (c) misconstrual of social and contextual cues that are useful for labeling states of arousal.

It is difficult in a single study to determine the extent to which some or all of these factors contribute to patients with FTD and AD endorsing more non-target emotions than controls. The findings that (a) FTD and AD patients did not differ from controls in non-target facial expressions and (b) facial expressions and subjective experience of non-target emotions did not significantly correlate with each other would argue against explanations involving differences in facial aspects of somatic nervous responding. Of course, facial expression is just one source of proprioceptive information in emotion; other muscle groups involved in changes to posture and activity (e.g., running away from something) are also rich sources of proprioceptive information [9]. As for other sources of information, we and others have found altered autonomic and somatic responding in FTD [23,24] and AD [34]. Alterations in the production and processing of interoceptive information are also likely given that brain regions critical to these processes such as the insula [7*,10**] are common targets of neurodegeneration early in FTD and in the later stages of AD [35,36].

Finally, we should note that patients with FTD and AD may also have changes in their ability to process social and contextual information that could influence their ability to label their emotional experience. Patients with FTD typically have neurodegeneration in anterior temporal regions thought to be critical for the processing of social information [37]. Patients with AD typically have neurodegeneration in the default mode network (consisting of medial and lateral temporoparietal and medial prefrontal regions [17*,38]), which is critical for self-referential processes [39]. Thus, patients with AD may have difficulty understanding external stimuli in relation to themselves (e.g., how does a boy crying in a movie relate to my internal experience?). Our findings that patients with AD reported more positive non-target emotions suggest that brain regions responsible for down-regulation of positive emotion may be particularly vulnerable in AD [21**,28].

Clinical Implications

The subjective experience of emotion is critical for functioning in the social world, undergirding our ability to communicate our emotional reactions and needs to others [5,16]. Results that patients with FTD and AD are more likely than controls to experience mixed subjective emotional experiences (i.e., consisting of both target and non-target emotions) when responding to laboratory film stimuli has important real-world implications. For example, patients with FTD and AD may present family members and caregivers with complex reports of their emotional states that consist of emotions that are normative and non-normative for a given situation. Caregivers may find these responses confusing or frustrating, which in turn can contribute to increased caregiver burden and other negative effects on caregivers’ health and well-being [40]. Additionally, patients with FTD and AD may report feelings that are not consistent with their facial expressions, creating additional complexities and difficulties for caregivers; studies examining dementia caregivers often find that patients’ emotional and behavioral symptoms are especially burdensome [41].

Conclusion and future directions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine mixed target and non-target emotions in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. The findings that patients with FTD and AD subjectively experienced more non-target emotions but did not display more facial expressions of these emotions compared to controls suggest alterations in the production and processing of relevant interoceptive information, and/or the evaluation of contextual information. Our study also has several limitations: (a) the film clips and ratings for subjective emotional responses were presented to the participants in the same order, and (b) we did not assess non-facial aspects of expressive behavior (e.g., body posture). Future research should be conducted to address these limitations and to identify the sources underlying disrupted subjective emotional experiences in FTD and AD, the impact that these mixed emotional states have on patients’ overall functioning and patients’ interactions with others, and the challenges mixed emotions create for caregivers and family members.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Greater subjective experience of positive and negative non-target emotions in FTD.

Greater subjective experience of positive non-target emotions in AD.

No differences in facial expressions of non-target emotions in either disease.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Aging grants RO1AG041762 and P01AG019724 to Robert W. Levenson. We thank Scott Newton and Kia Nesmith for subject recruitment, Deepak Paul for data management and technical support, and all research assistants for their assistance with data collection and the coding of facial expressions of emotion. We also thank all the patients and caregivers for their participation.

Footnotes

Note that the EEB coding system does not include positive non-target facial expressions for the amusement film clip and thus this variable could not be included in analyses.

The corrected scores were residual scores computed from regression models in which age, sex, dementia severity, emotion rating deficits, and self-reported target/non-target emotions were entered as predictors and self-reported non-target/target emotions were the dependent variable.

Note that data of dementia severity and emotion rating deficits were missing in 1 (NC) and 6 (5 FTD, 1 NC) participants, respectively.

The analyses for facial expressions of positive non-target emotions only included sadness and disgust film clips because the EEB coding system only codes for one positive emotion – amusement. Thus, no additional positive non-target emotions could be coded for the amusement film clip using this system.

Note that facial expressions of target, positive non-target, and negative non-target emotions were missing in 2 (1 FTD, 1 NC), 3 (2 FTD, 1 NC), and 2 (1 FTD, 1 NC) participants, respectively.

Note that the parallel analyses for facial expression of target emotions revealed a significant interaction of film clip x diagnosis, F(6, 416)=2.83, p=.01. This finding that patients with different diagnoses differed in their facial expression of the target emotion in response to the three film clips is consistent with previous findings from our laboratory [24] but is not of primary interest in the present study.

Figure 1A–C left shows that responses of FTD and AD patients fluctuated over the ten specific emotion questions, making it unlikely that perseveration accounted for our findings.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Levenson RW. Autonomic specificity and emotion. In: Davidson RJ, Scherer KR, Goldsmith HH, editors. Handbook of Affective Sciences. 2. Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 212–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotion elicitation using films. Cognition and Emotion. 1995;9:87–108. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coan JA, Allen JJ. Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell JA, Barrett LF. Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:805–819. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levenson RW. The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion. 1999;13:481–504. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett LF. The Future of Psychology: Connecting mind to brain. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:326–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *7.Craig AD. How do you feel now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature Review Neuroscience. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. This article proposes a neural model of how subjective experiences such awareness and emotional experience arise. Neuroimaging findings of brain regions activated during these processes are reviewed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Levenson RW. The Autonomic nervous system and emotion. Emotion Review. 2014;6:100–112. This article provides an overview of the role the autonomic nervous system plays in the generation and experience of subjective emotions. In particular, it reviews two kinds of patterned autonomic nervous system activity, coherence and specificity, while also discussing relevant issues regarding research methodology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.James W. What is an emotion? Mind. 1884;9:188–205. [Google Scholar]

- **10.Verstaen A, Eckart JA, Muhtadie L, Otero MC, Sturm VE, Haase CM, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Insular atrophy and diminished disgust reactivity. Emotion. 2016;16:903–912. doi: 10.1037/emo0000195. This study examined the association between insula damage and diminished subjective experience, peripheral physiology, and facial behavior of disgust in patients with various neurodegenerative diseases. Our study used the same approach as this study in terms of patient recruitment, diagnostic critera, and the coding of facial expressions of emotions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berntson GG, Norman GJ, Bechara A, Bruss J, Tranel D, Cacioppo JT. The Insula and evaluative processes. Psychological Science. 2011;22:80–86. doi: 10.1177/0956797610391097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen HJ, Levenson RW. The Emotional brain: Combining insights from patients and basic science. Neurocase. 2009;15:173–181. doi: 10.1080/13554790902796787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinstein JS, Adolphs R, Damasio A, Tranel D. The human amygdala and the induction and experience of fear. Current Biology. 2011;21:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with Schizophrenia revisited: Meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kring AM, Elis O. Emotion deficits in people with Schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:409–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keltner D, Haidt J. Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition & Emotion. 1999;13:505–521. [Google Scholar]

- *17.Seeley WW, Crawford RK, Zhou J, Miller BL, Greicius MD. Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron. 2009;62:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.024. This study demonstrates that subtypes of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease target distinctive large-scale brain networks. The findings provide readers with a greater understanding of the patterns of atrophy associated with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braak H, Braak E. Staging of alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiology of Aging. 1995;16:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathologica. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, Sheline YI, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Morris JC, et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:7709–7717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **21.Levenson RW, Sturm VE, Haase CM. Emotional and behavioral symptoms in neurodegenerative disease: A Model for studying the neural bases of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:581–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153653. This article summarizes the emotional and behavioral symptoms of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease by reviewing evidence from both clinical and laboratory research. It argues that examining neurodegenerative disease is an effective model for studying brain-behavior relationships. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng E, Marshall GA, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric features of dementia. In: Miller BL, Boeve BF, editors. The behavioral neurology of dementia. Cambridge University Press; 2011. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sturm VE, Ascher EA, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Diminished self-conscious emotional responding in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Emotion. 2008;8:861–869. doi: 10.1037/a0013765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eckart JA, Sturm VE, Miller BL, Levenson RW. Diminished disgust reactivity in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sturm VE, Yokoyama JS, Seeley WW, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Rankin KP. Heightened emotional contagion in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease is associated with temporal lobe degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:9944–9949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301119110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiota MN, Levenson RW. Turn down the volume or change the channel? Emotional effects of detached versus positive reappraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;103:416–429. doi: 10.1037/a0029208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturm VE, Yokoyama JS, Eckart JA, Zakrzewski J, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Seeley WW, Levenson RW. Damage to left frontal regulatory circuits produces greater positive emotional reactivity in frontotemporal dementia. Cortex. 2015;64:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross JJ, Levenson RW. Emotional suppression: Physiology, self-report, and expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:970–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.6.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles ST. Viewing injustice: Greater emotion heterogeneity with age. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:159–164. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gross JJ, John OP. Facets of emotional expressivity: Three self-report factors and their correlates. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;19:555–568. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schachter S, Singer J. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review. 1962;69:379–399. doi: 10.1037/h0046234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith M. Facial expression in mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Behavioural Neurology. 1995;8:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foundas AL, Leonard CM, Mahoney SM, Agee OF, Heilman KM. Atrophy of the hippocampus, parietal cortex, and insula in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology. 1997;10:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen HJ, Gorno–Tempini ML, Goldman WP, Perry RJ, Schuff N, Weiner M, Feiwell R, Kramer JH, Miller BL. Patterns of brain atrophy in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:198–208. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olson IR, Plotzker A, Ezzyat Y. The Enigmatic temporal pole: A Review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain. 2007;130:1718–1731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer’s disease from healthy aging: Evidence from functional MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheline YI, Barch DM, Price JL, Rundle MM, Vaishnavi SN, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA, Wang S, Coalson RS, Raichle ME. The Default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:1942–1947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812686106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: Prevalence, correlates, and causes. The Gerontologist. 1995;35:771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong C, Merrilees J, Ketelle R, Barton C, Wallhagen M, Miller B. The Experience of caregiving: Differences between behavioral variant of Frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20:724–728. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318233154d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]