Abstract

Objectives

This paper explores the understanding and practice of patient‐centred care (PCC) within dentistry. The aim of the research was to explore the nature of PCC, how PCC is taught and how it is practiced within a dental setting.

Methods

The results of a qualitative, interview‐based study of dental professionals working across clinical and teaching positions within a dental school are presented.

Results

Results suggest that a shared understanding of PCC revolves round a basic sense of humanity (‘being nice to patients’), giving information that is judged, by the clinician, to be in the patient's best interest and ‘allowing’ patient choice from a set of choices made available to patients by the clinicians themselves.

Conclusions

This research suggests that significant work is needed if dentists are going to conform to the General Dental Council guidelines on patient‐centred practice and a series of recommendations are made to this end.

Keywords: dentistry, patient‐centred care

Introduction

Patient‐centred care (PCC)1, 2, patient empowerment and the giving of choice to patients over decisions to do with their health have been popular ideas in medical settings.3, 4, 5 Within these settings, PCC has been defined as being a process where ‘Providing care…. is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’.6 Thus, PCC is a mode of health‐care delivery that puts the patient at the forefront of all decision making and treatment.

PCC has been associated with tangible benefits in physical and psychological outcomes7 and as such has been adopted by health systems such as the UK's NHS.8 In the recent UK NICE guidance8, for example, a set of 14 principles were outlined all of which aim to make the experience of adults using the NHS more patient‐centred. These principles range from the most basic standard of the need to treat patients with dignity, kindness, compassion, courtesy, respect, understanding and honesty (principle 1), to patients being actively involved in shared decision making, supported in making decisions about treatment that are important to them (principle 6) and experiencing care that is tailored to their needs and personal preferences (principle 9).

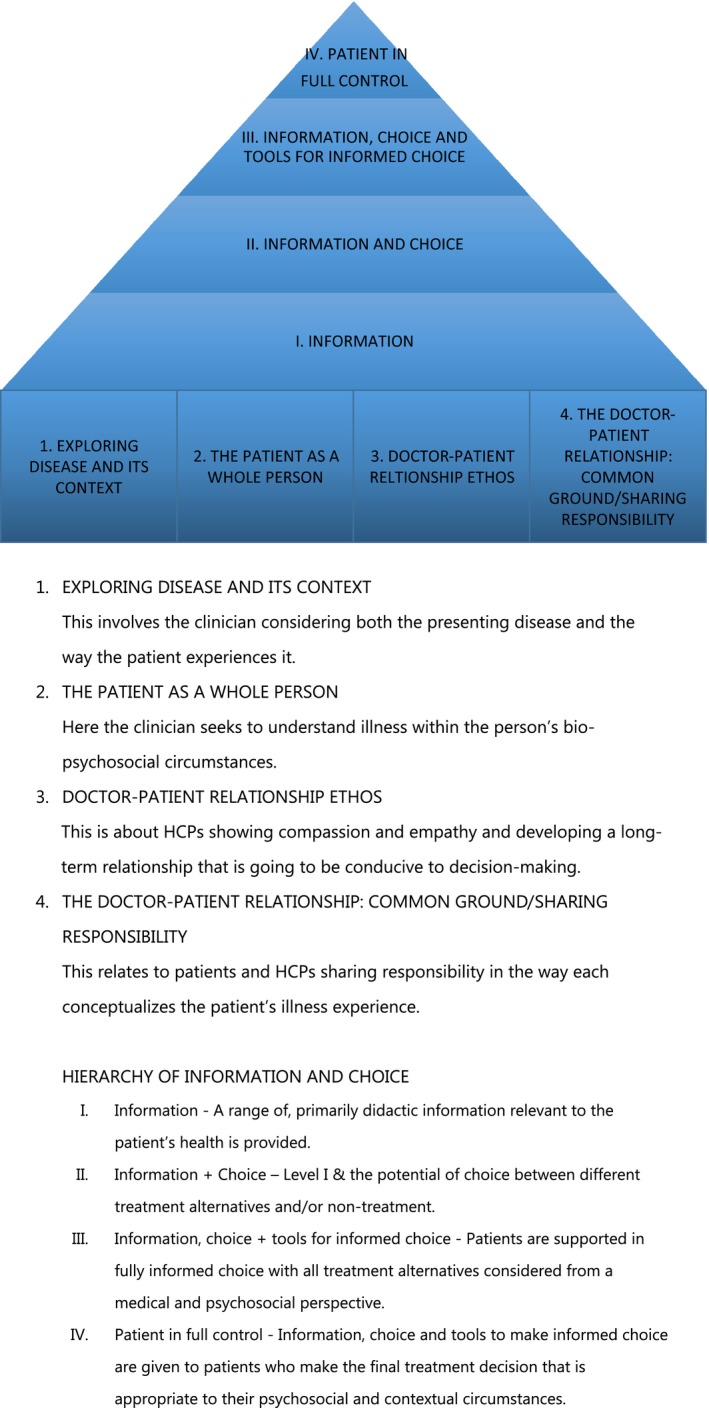

At the same time, much work has been done establishing a theoretical model for patient‐centred practice culminating into two popular frameworks1, 9 incorporating the wider patient context and aspects of the doctor–patient relationship. Building on these frameworks and focusing on their similarities rather than their differences, we have argued previously10 that PCC may be conceived as a concept consisting of four foundational components (constructs 1–4) based on the work of Mead and Bower1 and Stewart et al.9, which pave the way for a practical, five‐level hierarchy of information and choice, based on our work.10

This framework of PCC thus rests on key components around treating the patient within their psychosocial context and building on a strong ethos of a health‐care professional–patient relationship that strives to share responsibility. The model proposes that there are qualitatively more (or less) patient‐centred ways for clinicians to give information and choice to patients.

Although both the academic literature and practical recommendations to clinicians through NICE endorse PCC, the extent to which these ideas have truly transferred into medicine or in this case dentistry, remains unknown. The UK General Dental Council (GDC) Standard for Dental Professionals, for instance, sets out the principles that dental professionals should follow. The principles are fairly prescriptive and the Council's recommendation is that these principles should influence all areas of practice. Within this GDC document, Standard 2 is about ‘Respecting patients’ dignity and choices'. Here, it is explicitly stated that Dental Professionals should ‘recognise and promote patients’ responsibility for making decisions about their bodies, their priorities and their care…. .11

The above statement, although making explicit the need for dentists to be patient‐centred in a way that patients are encouraged to have some responsibility about decision making in a dental consultation, does not clearly identify the details of this process. It further fails to differentiate between different contexts and professionals or indeed give examples of how GDC members might implement this standard in day‐to‐day clinical practice.

Given the popularity of PCC as a NICE‐recommended idea and the need for dentists to work alongside patient‐centredness principles as part of the GDC standards governing their practice, we wished to explore what practising dentists understand by the concept of ‘PCC’, how they have learned about it and how they practice it in day‐to‐day clinical work.

The research question(s) addressed by this study are thus

What is PCC from a practicing dentist's perspective?

How do dentists get taught to practise in patient‐centred ways?

How does PCC get practised in dental surgery?

Method

Participants were recruited from one large dental school in the UK and comprised qualified dentists who (i) were involved in either NHS and/or private service provision and (ii) were responsible for teaching dentistry to undergraduates. Sample criteria were set to include current practitioners who were also involved in the academic delivery of the subject to try and reach practitioners who were in touch with current academic debate on the subject of patient‐centredness and also involved in the development of the next generation of dentists.

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling; eligible participants (N = 47) were targeted via e‐mail, in a message outlining the study and inviting them to participate in an anonymous, confidential, face‐to‐face interview. Where participants responded (N = 8), an appointment was made for a meeting with the researcher. Where no response was received initially, a reminder email was sent. In the end, N = 20 participants were recruited into the study giving a 42% response rate.

The sample was predominantly male (N female = 6), middle‐aged (M age = 45.15, SD = 10.20 years) and most had qualified in Europe (N = 17). They ranged in the years they had been practising dentistry (range 3–36 years) but on average, they were experienced practitioners (practising dentistry M = 21.95, SD = 10.49 years). Half were General Dental Practitioners, whilst the other half were specialists in a wide range of areas. Although small from a quantitative, experimental paradigm, using samples of this size has been shown to be an efficient, practical and yet robust strategy to obtain rich data, explore understanding and identify emerging themes in qualitative, in‐depth semi‐structured interview designs.12

Data were collected through semi‐structured interviews using an interview schedule to ensure that all areas of interest were covered but allowing for flexibility to pursue issues as they arose. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, and the data were analysed using a thematic framework derived from the literature and modified throughout the analysis process, following the standard four‐stage process (familiarization, coding frame development, coding, compiling themes).13

The study was given clearance to take place by a University Ethics Committee and was conducted in line with usual guidelines pertaining to participants' right to anonymity, confidentiality and withdrawal.

Findings

Dentists were asked to define PCC, to speak about when, where, how and if they had come across the concept, whether they practiced it and if so how.

What became apparent was that there is no universal understanding of the concept of PCC and there is no formal structure through which PCC is currently being taught within the undergraduate dental curriculum. Interestingly, however, all of those interviewed were convinced that they practiced PCC and most talked about picking it up through intuitive practice rather than formal training.

The results are presented in three parts. First, definitions of PCC are presented. The following section explores themes that emerged regarding the dentists' everyday practice in patient‐centred ways. Finally, we present a section on where dentists' understanding of PCC arose from. Quotes are used throughout to illustrate the themes that emerged from the data and are identified by interview, page and line numbers.

Section 1: Defining PCC

Interviews started with a question about defining PCC. The vast majority of the participants were quite confident in providing definitions of PCC and only three expressed some concern over their interpretation. There was no universal definition of PCC, but the definitions provided fell within six broad themes:

Individualized care;

Care in the best interests of the patient;

Humanity;

Holistic care;

Patient involvement;

Political construction.

Individualized care

This theme focused on putting the patient at the centre of care and ensuring that all of their clinical oral health needs were met. For some, this involved joined‐up care, that is, the various dental specialties working together. At a basic level, careful care planning was seen as necessary to provide:

…dental care that is specifically tailored to the individual patient.

54:2:26–28

Related to this, is the next theme, which, in addition to seeing people as individuals, suggests that PCC is about doing what is best for the patient.

Care in the best interests of the patients

Here, PCC was about the provision of care that met the clinical needs of the patient. For some, this involved the provision of quality, competent care by a clinician with appropriate technical expertise, tailored to the specific needs of the patient.

I think PCC primarily can be defined as the treatment or care of the patients' clinical needs in the patients' best interest.

53:2:38–40

Others included within this the permission of the patient:

I always thought we are meant to be doing what was best for the patients with their permission.

46:2:45–46

Whilst clearly for some, the views of the patient were secondary:

Essentially it is always centred around the patient's best interest, which the patient may or may not agree with but the decision‐making process always involves the patient's best interest.

53:3:61–64

Humanity

The most common definitions of PCC were general and focused on the interaction between the clinician and their patient. The focus was not, however, on communication or the provision of information to patients but more about the clinician's attitude. Dentists talked about treating patients with compassion and dignity, or ‘as you would want to be treated’. Additionally, they talked about being ‘frank’, ‘honest’, ‘open’, ‘fair’ and ‘trustworthy’. These were seen as the central components of a patient‐centred approach to care.

Whilst there is little doubt that these are reasonable and desirable aspects of any consultation, it is interesting to note that our dentists' definitions of PCC do not move beyond this basic interaction based on shared humanity.

Holistic care

Two participants included the idea of holistic care within their definition of PCC. Of these, one explained what this entailed.

….tailored to the particular patient's needs so understanding like psychosocial characteristics…

57:3:50–52

This was the only participant who incorporated the wider psychosocial context explicitly into the definition. Although a popular term, no further detail was provided on what holistic care actually entails, by any of our participants.

Patient involvement

Four of the participants specifically included patient involvement in their definition of PCC. There was a view that treatment would not work unless the patient was involved, although the level of involvement varied. One participant talked about achieving balance:

There is not what the patient or what the dentist say it's just a balanced decision.

59:2:43–44

Whilst others talked about meeting the requirements of the patient:

I presume you mean umm…. practicing high quality care according to patients' aspirations, wishes and requirements rather than the dentist saying ‘this is what you have to do’.

49:2:35–38

One participant talked specifically about making the patient happy.

I know pursuit of happiness is not considered to be an important part of dentistry which a lot of it is.

46:5:138–139

Interestingly, although many participants talked about wanting to achieve patient satisfaction, or avoid dissatisfaction, the idea of wanting to ‘make patients happy’ was also seen as a potential pitfall in relation to the need to balance what patients want with what clinicians feel that they need.

One final participant was quite specific about the type of involvement that patients should have in order for practice to be patient‐centred. This revolved around acceptance of responsibility:

PCC is exactly that – it's care which revolves primarily around the patients' attitudes, abilities, understanding of what is wrong with them. It's understanding how their behaviour ties in to the consequences.

50:3:48–51

…a lovely phrase the NHS uses a great deal but what it actually means is another thing, because PCC doesn't mean the patient has the right to dictate absolutely everything. That's not what PCC means. PCC is about responsibility, it's about the fact that actually 99% of the problems the patient brings to the dentists are their own fault and they need to be made to realize that and fix it in whatever way.

50:12:277–288

This participant went on to suggest that patients need to take responsibility for the oral health problems that they encounter if they are related to the behaviour that they choose to engage in. In this instance, patient‐centredness is seen as the patient taking responsibility for their oral health, not in relation to shared decision making or informed consent so much, as risk management.

A political construction

The final theme relates to the wider context in which PCC has emerged. For some, it was simply a marketing tool, rebranding work that already takes place in the form of good practice:

I think it's politics and marketing, it's been… I would say I wouldn't go as far as saying its rubbish, but it's branding.. (Laugh).

55:7:159–161

On a completely different note, one participant saw PCC as the gold standard, promoted by the government:

The government and the professional bodies are certainly trying to make it the way forward, this is the gold standard.

58:5:131–132

Here, the view was that PCC was a way of making the patient journey good for the patient and raising patient satisfaction levels as well as the quality of care.

It is worth noting that these six themes reflect the ‘definitions’ of PCC as seen by participants. It should be obvious that there is a range of interpretation of what the term actually means. Interestingly, when the same participants were asked to talk about their own practice of PCC, further themes emerged, some of which were extensions of the definitions seen so far.

Section 2: PCC in practice

In an attempt to gain a more nuanced understanding of PCC in dentistry, participants were asked to describe clinical encounters where they practiced in a patient‐centred way and to identify what it was about the practice that was patient‐centred. Three themes emerged here, one of which (Patient Involvement) overlaps with the earlier definitions of PCC. The emergent themes, which we explore next, were

Communication and Rapport;

Patient involvement;

Patient choice.

Communication and rapport

Communication was addressed explicitly in four of the descriptions of PC practice given. This incorporated the need for clear verbal and written communication using accessible, appropriate language and providing information in different formats. One participant explained:

I talk to them, I try and explain very clearly in language they understand what we are at. What position they are at and what's likely to happen to them next, one way or another.

46:3:66–68

The need to build good rapport was also reported whilst one participant highlighted the need to tailor communication styles to different patients:

I am not a psychologist but I don't believe that there is a right and a wrong way. For some patients you may have to stand there and scold them, there's others you may have to scare them, there's others you know you can do completely the opposite, there are others you know you have to do a mixture of the two.

50:13:309–314

The rather paternalistic choice of words here, raises issues about power, choice and control within the consultation, factors that may influence how the next theme, patient involvement, gets enacted in practice.

Patient involvement

The majority of participants talked about the need for patients to feel involved in the treatment process. The interesting distinction here is between patients ‘being’ involved and ‘feeling’ involved and the choice of language used to describe their ability to participate in their care:

They need to feel that they are being treated with respect and they are being trusted to make important decisions. Lots of patients are quite intelligent, quite capable of making all their decisions.

46:4:95–97

Other participants focused on the importance of meeting the needs of their patients; such patient ‘aspirations’ may be expressed by the patient but are more likely to be clinician‐led:

I would say that you know the patient's wish for the choice of options is obviously the most important thing and I suppose to some extent one of the jobs of the dentist is to actually have the patient realize their aspirations.

49:7:165–168

Participants saw meeting patient aspirations as, however, about balancing aspirations, clinical need, technical skills and the system:

…find the balance between patient demands, patient expectation, what is within one's own technical and clinical ability to provide and you obviously have to take into account any restrictions within the system within which you are working.

62:2:28–31

This balancing exercise was further clarified by a second participant who highlighted the need to counter ‘unreasonable’ demands or aspirations:

… not submitting to unreasonable demands or expectations of the patient… such as the excessive use of some forms of cosmetic dentistry which involves destruction of large amount of healthy tooth tissue. Umm and I will refuse to carry out treatment in some cases no matter what the patient wanted.

62:2:43–52

It is, thus, important to involve patients in their treatment and meet patient needs and aspirations as long as these are judged reasonable and practicable by the clinicians involved. This leads on and has implications for the theme of patient choice.

Patient choice

Just over half of the participants addressed the issue of patient choice. In practice, at the most advanced level, information is provided and the patient is enabled to make an informed choice:

Well I'll say ‘it's not really my job to make the decision for you, it's just to tell you what the options are and risk and benefits you have for each one.

55:7:152–154

The information provided with which to make an informed choice may, however, be influenced more or less overtly by the clinician's view of treatment need and appropriate treatment options that the dentist feels the patient might ‘need’.

I think for me PCC means autonomy for the patient to be able to make informed decisions based on what we as clinicians are able to tell them about the treatment that they need.

52:3:61–63

In order to try and unpick the concept of choice, participants were asked what would happen if patients did not choose the option favoured by the clinician. This produced some interesting results. Again, the choice of language elucidates the inherent biases present. Information is provided in such a way so as to enable patients to make the ‘sensible’ informed decision:

I try and explain to the patient precisely what is wrong or right. What their condition or problem might be. And what are the different options of the treatment and how they might… what their choices might be and make sure that they are involved in understanding of what is being done or what might be done. And what the advantages or disadvantages of each are so they do make sensible informed decisions.

46:2:51–56

For some, the difficulty comes when a patient wants to make a choice which is not in their best interest:

So, the patient and the dentist have a roughly equivalent input. The only exception being where a patient's requirements of you are not in their best interest.

48:4:71–73

Thus, for these participants, patient choice is allowed only within the perimeters of clinically judged best interests.

Patients who insisted on making the ‘wrong’ choices were encouraged to comply or seek treatment elsewhere.

I don't try to convert the patient to what I think should be done because I don't feel that is my place. I think we are there to carry out treatment with which we are both happy with. If they ask me to do something I am not happy with then I'll say ‘I am not happy to do that but somebody will do it for you. But not here, you'll have to go somewhere else.

47:6:133–139

In these examples, the nature of the ‘choice’ given raises questions about the extent of patient‐centredness within the consultation; if choice is taken to be a key component, the potential clash between a clinician's need to provide a patient‐centred consultation and their duty of care towards the patient is highlighted.

Finally, our sample reported on where they had learned about PCC.

Section 3: Learning to be patient‐centred

When asked whether they engage in PCC, all of the participants in this study were unequivocal in their belief that they did:

I totally do it all the time.

46:2:48

And yet when asked where they had learned their PCC skills, it was agreed that there was little or no formal teaching and that most knowledge around PCC was acquired ‘on the job’.

…always I don't know when or why I suddenly decided what I had to do but I have always done it from the beginning.

58:2:54–56

These two themes are discussed below.

Learning PCC through explicit teaching

Only two participants talked specifically about incorporating PCC in to their teaching routinely, focusing on information provision to support decision‐ making:

We teach our students in whatever they do they have to inform the patients and it's up to the patient to make an informed decision about their own treatment. That that's I think the key thing we talk to them about, we teach them.

52:2:35–40

And in a more general sense, inviting student dentists to treat the whole person:

I do always mention that we are treating a patient not a mouth and a patient is a person and we have to…. It's like we are working to keep them happy and it is important to give them consent or what they want or balance of what we suggest and what they want within that agreement.

59:1:22–25

Learning PCC in practice

What is most striking is that the majority of participants (n = 16) stated that they had no formal or informal training on PCC, what it means or how it should be practised. Some learned on the job through watching senior colleagues (who themselves had no formal training), but the majority suggested some sort of subconscious or innate knowledge about what to do and how to do it.

I think unconsciously I have always done that…… I have always allowed them to make their own decisions.

52:4:72

Interesting here is the choice of words – patients were ‘allowed’ to make their own decisions. This raises questions about the nature of the choices that patients were given, tying in with the earlier definitions of PCC and their relationship to patient choice. It is also worth bearing in mind here that there was little difference in the definitions provided by more or less senior participants, which again, raises questions about the skills being passed down.

What becomes apparent in analysing these data is that the shared understanding of PCC revolves round a basic sense of humanity (‘being nice to patients’), giving information that is judged, by the clinician, to be in the patient's best and ‘allowing’ patient choice from a set of choices made available to patients by the clinicians themselves. In addition, there is no formal, and very little informal, teaching on PCC and participants have an innate knowledge about how to be patient‐centred, which they are all confident they are enacting on a daily basis.

Discussion

Official health/oral health documents are increasingly focusing on the need for a patient‐centred approach to the provision of PCC within a patient‐centred health‐care system. And yet, little has been done to ensure a shared, consistent and practicable understanding of the concept of patient‐centredness amongst health care professionals charged with providing this form of care. This paper sought to explore the attitudes and understandings of PCC amongst dentists as part of a wider study which also encompassed barriers to PCC, such as the nature of the health‐care system in which they are working. These findings are being presented elsewhere, due to article length. Limitations of the current study include the nature of the sample used, which was limited (deliberately) to a single dental school and to participants who both practice clinical dentistry and are involved in teaching undergraduate dental students. Future work in this area could include a larger study encompassing General Dental Practitioners from a wider geographical area and incorporating NHS, private and mixed dental practices.

Research in medicine has demonstrated that there is quite a significant, shared understanding of the term in theory2, 10, 14 with the medical profession now moving on to focusing on how the concept should be practiced in the clinic.10 Within dentistry, however, work is needed, building on helping dentists acquire a sound theoretical understanding of the foundational components of PCC, before we consider how PCC might be practiced in dental surgery. Whilst many of our participants considered at least some of the four foundational components1, 9 (particularly evident within the holistic and patient involvement themes, and also touched on in relation to communication), the results seem to indicate that this sample was working within level 1 of the information provision and choice framework (Fig. 1) with references to choice indicating the provision of a bounded or limited set of choices, arguably akin to no choice at all. This is particularly concerning due to the nature of the sample in this study, all participants are practicing dentists and also involved in teaching undergraduate dental students. This suggests that not only is a training programme, ideally with tools to use in clinic, needed for existing dentists, it may well be needed for future dentists too.

Figure 1.

A practical hierarchy of patient‐centred care.

In conclusion, we suggest that if dentistry is to provide truly PCC, then three things need to happen. The first is that the theory of PCC needs to be embedded within the undergraduate dental curriculum throughout the 5‐year BDS course. This should be done explicitly through the teaching of the theory and definitions of PCC and the embedding of this approach within all streams of the curriculum as an integral part of clinical, diagnostic and communication work and should incorporate individual, community and population‐level understandings of the patient drawing on sociology, epidemiology and psychology. Our second recommendation is that practical skills are taught explicitly. Patient‐centred care is very difficult to practice well and students need to develop the skills necessary to practice in a patient‐centred way. These include, but are not limited to, communication skills, the theory and practice of behaviour change and managing pain and anxiety, underpinned by a thorough knowledge and understanding of the importance of evidence‐based practice. Finally, our third recommendation would be that the theory and skills of PCC are developed as part of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for dentists who are already practicing but have not received training in this area. If these recommendations are adopted, then we will move a step closer to meeting the GDC and NICE recommendations regarding the provision of PCC within dentistry.

Funding and conflict of interest

This study was not funded, and there are no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all of the dentists who agreed to participate in the interviews.

References

- 1. Mead N, Bower P. Patient‐centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science & Medicine, 2000; 51: 1087–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mead N, Bower P. Patient‐centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling, 2002; 48: 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newton P, Asimakopoulou KG. A response to Professor Anderson's commentary on Empowerment article by Asimakopoulou, K. European Diabetes Nursing, 2008; 5: 36. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asimakopoulou K, Gilbert D, Newton P, Scambler S. Back to basics: re‐examining the role of patient empowerment in diabetes. Patient Education and Counseling, 2011; 86: 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Asimakopoulou KG. Empowerment in the self‐management of diabetes: are we ready to test assumptions? European Diabetes Nursing, 2007; 4: 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine . Crossing the quality chasm, 2001. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=0309072808, Accessed 26 March 2013.

- 7. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient‐centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Medical Care Research and Review, 2012; 70: 351–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. NICE . Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services: Clinical Guidelines (CG138), 2012. Available at: http://publications.nice.org.uk/patient-experience-in-adult-nhs-services-improving-the-experience-of-care-for-people-using-adult-cg138 Accessed 26 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stewart M, Belle Brown J, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient‐Centred Medicine: Transforming the Clinical Method. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Asimakopoulou K, Scambler S. The role of information and choice in patient‐centred care in diabetes: a hierarchy of patient‐centredness. European Diabetes Nursing, 2013; 10: 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11. GDC . General Dental Council Standard Guidance. London: GDC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crouch M, McKenzie H. The logic of small samples in interview‐based qualitative research. Social Science Information, 2006; 45: 483–499. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Green J. The use of focus groups in research into health In: Saks M, Allsop J. (eds) Researching Health: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods. London: Sage, 2007: 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asimakopoulou K, Newton P, Sinclair AJ, Scambler S. Health care professionals' understanding and day‐to‐day practice of patient empowerment in diabetes; time to pause for thought? Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 2012; 95: 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]