Abstract

Background

Early treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is vital. However, people often delay in seeking help at symptom onset. An assessment of the reasons behind patient delay is necessary to develop interventions to promote rapid consultation.

Objective

Using a mixed methods design, we aimed to develop and test a questionnaire to assess the barriers to help seeking at RA onset.

Design

Questionnaire items were extracted from previous qualitative studies. Fifteen people with a lived experience of arthritis participated in focus groups to enhance the questionnaire's face validity. The questionnaire was also reviewed by groups of multidisciplinary health‐care professionals. A test–retest survey of 41 patients with newly presenting RA or unclassified arthritis assessed the questionnaire items' intraclass correlations.

Results

During focus groups, participants rephrased questions, added questions and deleted items not relevant to the questionnaire's aims. Participants organized items into themes: early symptom experience, initial reactions to symptoms, self‐management behaviours, causal beliefs, involvement of significant others, pre‐diagnosis knowledge about RA, direct barriers to seeking help and relationship with GP. The test–retest survey identified seven items (out of 79) with low intraclass correlations which were removed from the final questionnaire.

Conclusion

The involvement of people with a lived experience of arthritis and multidisciplinary health‐care professionals in the preliminary validation of the DELAY (delays in evaluating arthritis early) questionnaire has enriched its development. Preliminary assessment established its reliability. The DELAY questionnaire provides a tool for researchers to evaluate individual, cultural and health service barriers to help‐seeking behaviour at RA onset.

Keywords: delay in accessing health services, face validity, patient involvement, questionnaire development, rheumatoid arthritis, test–retest reliability

Background

Irreversible joint damage occurs during the early stages of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The first 3 months following clinical disease onset represent a therapeutic window during which drug treatment is particularly effective at controlling synovitis and limiting subsequent damage to bone and cartilage.1, 2, 3, 4 Despite increased recognition of the benefits of early treatment, there remains considerable delay between symptom onset and the initiation of therapy.5, 6, 7 Delays can occur at several levels including delay on the part of the patient in seeking medical advice at symptom onset, delay in obtaining an appointment with a primary health‐care professional and delays in referral to a rheumatologist, diagnosis and commencement of disease modifying therapy.8, 9 The median delay between symptom onset and assessment by a rheumatologist in the UK has been reported to be 23 weeks, most of which was due to patient delay in seeking help (median 12 weeks).7, 10 Similar delays occur in many other European countries.11, 12 Many patients thus miss a potential therapeutic window because they delay in seeking help for their symptoms.

Qualitative studies and a meta‐synthesis have identified barriers to help seeking at the onset of RA.13, 14, 15, 16 Barriers to early consultation included the insidious onset of symptoms which often characterize the onset of RA. Patients often normalized their symptoms and did not consider arthritis as a potential cause. Pre‐existing ideas about RA, often termed prototypical illness beliefs (cultural understandings of an illness held by people without personal experience of the illness in question), led people to believe that RA was a mild condition that affected older people. These misperceptions made correct symptom interpretation unlikely. Prototypes for some illnesses are better formed than those of others, but generally they influence individuals' perspectives on an illness' likely duration, its symptomatology, severity and consequences and the need for treatment.17, 18 These prototypical models can be unhelpful if they are inaccurate and may mislead people into believing that the symptoms of conditions such as RA do not require them to seek medical attention.

In addition to symptom experience, the influence of advice from family and friends, a frequent desire to use alternative medicines, access to health services and attitudes towards health‐care professionals, particularly general practitioners, are also important determinants of help‐seeking behaviour.15, 19 Further research is needed to understand the importance of the range of barriers to seeking help identified through qualitative research and which barriers are relevant to different groups within the population. A method of systematically measuring barriers to seeking help at the onset of RA is thus required. A tool to measure barriers would allow the relationship between determinants and extents of delay in help seeking to be assessed. A cross‐sectional survey using this tool would provide an evidence base from which tailored interventions to promote rapid help seeking could be developed.

Exploring the perspectives of people with a lived experience of RA has been instrumental in determining the research priorities for people with RA and the development of appropriate measurement tools used to assess RA.20, 21, 22, 23 Furthermore, involving patients in questionnaire development can ensure that the questions used were appropriate, relevant and comprehensible to the target population.24, 25 The use of qualitative methods to explore themes discussed in the questionnaire can help identify salient attitudes and norms, inform the content, format and layout of a measurement tool and provide information about user‐friendliness.26, 27

In this study, we describe the process of developing, validating and reliability testing the DELAY (delays in evaluating arthritis early) questionnaire, which was developed to assess the barriers to help seeking at RA onset. This research was undertaken in collaboration with two patient research partners who acted as co‐facilitators during focus groups and were involved in the analysis and interpretation of qualitative data.

Methods

Integrated approaches were used to develop items for a questionnaire about help‐seeking behaviour at the clinical onset of RA.28 First, the research team identified potential items for inclusion from a synthesis of the literature regarding help‐seeking behaviour in patients with RA.15 Second, people with a lived experience of RA and joint problems participated in focus groups to discuss and further develop the questionnaire item pool and to explore item wording and questionnaire structure. During the third phase, focus groups were held with health‐care professionals who reviewed the questionnaire for face validity. Finally, we undertook a test–retest study to assess the reliability and stability of responses to questionnaire items. NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained for this study (reference: 10/H1207/98, issued 19/11/2010), and all participants gave written informed consent. Methods for each of these approaches are described below.

Initial questionnaire construction

Initially, 28 questionnaire items were derived from our group's qualitative interviews with people with RA.13, 14 Our systematic synthesis of the qualitative literature15 regarding the barriers to help‐seeking behaviour at RA onset increased the number of questionnaire items to 54. One or more statements were written to represent each concept identified from the existing literature. The questionnaire items were organized into themes, and a draft of the DELAY questionnaire was structured to allow respondents to indicate their agreement with each questionnaire item using a five‐point Likert scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree).

Focus groups to discuss the relevance of potential questionnaire items

Twenty‐three individuals were invited to participate in a series of focus groups to develop and validate the individual questionnaire items and the overall presentation of the DELAY questionnaire from the perspective of those with a lived experience of arthritis. Participants were recruited from local arthritis charities and patient support groups. Participants were 15 people diagnosed with RA, four with other arthritic conditions and four who were related to people with RA. RJS and two Patient Research Partners (IR and ST) co‐facilitated the focus groups. Focus groups were guided by a topic guide developed by a multidisciplinary team (including IR, ST, RS, KR, RH, SHM and KS). The topic guide encouraged participants to share and reflect on experiences of help seeking at RA onset. The topic guide also addressed whether items should be rephrased, added or removed and to critically appraise the overall questionnaire in terms of structure and organization, comprehensibility, feasibility and acceptability.

Three focus groups with 19 health‐care professionals (HCPs) including four consultant rheumatologists, two rheumatology trainees, three rheumatology nurse specialists, one practice nurse and nine general practitioners were conducted to offer insight into patient delay across a range of settings. HCPs were identified though advertisements in local rheumatology and academic centres.

The focus group discussions were digitally audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by RJS. Data were analysed using inductive thematic analysis methods.29 Initial coding was used to generate analytical summaries of accounts. Blind independent initial coding of a sample of transcripts was undertaken by RJS and KR. The initial codes were grouped together into most noteworthy and frequently occurring categories, and related categories were linked together using qualitative data analysis software.30 The themes were reviewed by RJS, KR (academics), ST and IR (patient research partners) who discussed changes to be made to the questionnaire and individual questions.

Test–retest study

The revised questionnaire was subject to a test–retest survey over two time points to establish item stability. Survey participants were patients aged 18 years or above and had RA (according to the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria)31 or unclassified arthritis (UA). Ninety‐one patients with newly presenting RA or UA were approached by the assessing rheumatologist or nurse specialist in secondary care rheumatology clinics. Those who consented were asked to complete the DELAY questionnaire and return it using a freepost envelope.

Those who returned their first questionnaire were sent a follow‐up copy of the DELAY questionnaire; the follow‐up was sent approximately 2 weeks after the first questionnaire was returned. If the follow‐up questionnaire was not returned within 1 week of it being sent to the participant, one postal reminder was sent. Answers given to questions at baseline and follow‐up were compared using intraclass correlations. This statistic shows how strongly the scores given at each time point resemble one another. It was pre‐specified that statements with correlations which were significant at the 1% level would be classified as having good test–retest reliability and the other statements would be considered to have poor test–retest reliability.

Findings

Focus groups with people with a lived experience of arthritis

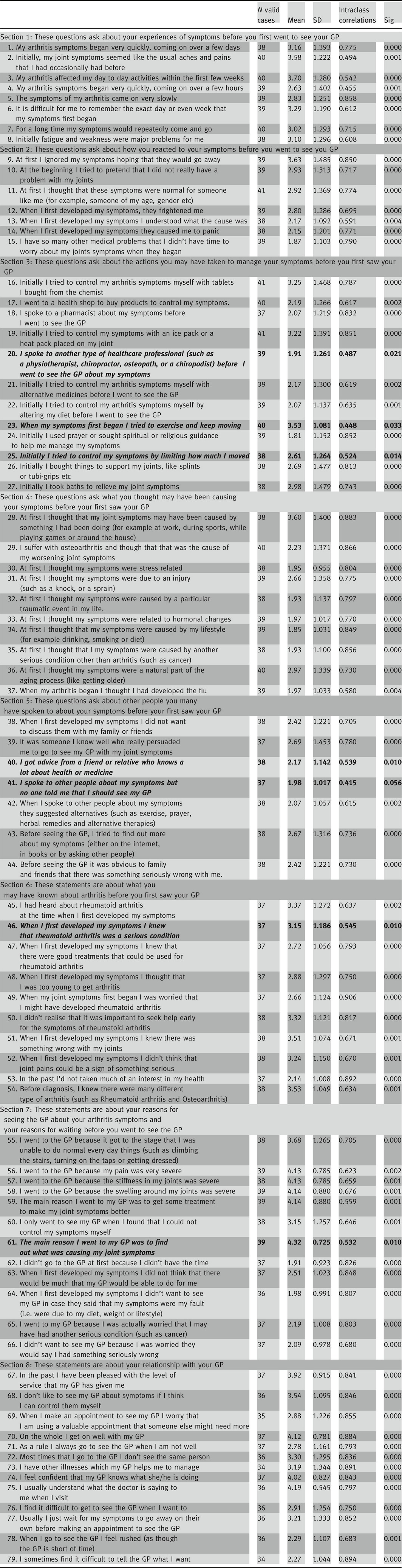

The findings presented here are a summary of how the focus groups were used to inform the draft 54 item questionnaire developed from the existing qualitative literature. During the focus groups, additional items and concepts were proposed, and changes were made to the original items. Statements were organized into eight sections (which have been used as subheadings below): Experience of symptoms before seeing GP; Reactions to symptom onset; Initial self‐management of symptoms; Beliefs about the cause of symptoms; Talking to others about symptoms; Knowledge about RA before diagnosis; Direct barriers to GP consultations (such as personal circumstances or environment); and Communication and relationship with GP. This process enhanced the questionnaire's face validity and increased the number of questionnaire items to 79. The findings are supported by quotations from focus group participants. The revised questionnaire items are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

DELAY patient questionnaire items including results of intraclass correlation analysis (deleted items are in bold italics)

Section 1: symptom onset

Participants agreed that the core symptoms of pain, fatigue, swelling and stiffness were covered by the draft DELAY questionnaire, but suggested that the questionnaire should refer to ‘symptoms' as an overarching descriptor, instead of referring to specific symptoms (see questions 1–7 Table 1). For many, fatigue stood out as a prominent symptom; therefore, item 8 was dedicated to this issue.

This should be major problem not just problem. I have fallen to sleep while driving and I can fall to sleep while talking to people, it's like a switch, a wave of exhaustion. You should change the question.

(Participant with RA: Focus group four).

Participants were keen for the questionnaire to capture the different types of symptom onset and represent the different intensities of symptoms experienced by people at disease onset. Questions 1, 4, 5, 6 and 7 were modified from existing statements to create items representing the different types of symptom onset.

Severity is one of the problems, the onset of the problem, so if the onset is insidious or slow and you may ignore it. Obviously if it's very severe and it interfering with their activities of daily living or employment then….. they may need to access some sort of health professional as soon as they can suppose.

(Participant with RA: focus group five).

It was highlighted that the proposed methodology was to administer this questionnaire to patients at their initial presentation in secondary care. It was also noted that there was often considerable delay between initial presentation to the GP and assessment in secondary care; therefore, it was felt important to emphasize that the time period being asked about in the questionnaire was that prior to presentation to the GP. Participants suggested that some questions could be subject to misinterpretation, because some items asked about symptoms that for many people with RA would be on‐going problems and that responses may reflect current symptoms rather than symptoms prior to initial consultation with a health‐care provider.

I suppose if you're asking someone if that was something that affected them straight away, you might be able to put it in a better way. You could say ‘did fatigue affect you straight away’. Because people will get confused, they will think – I've still got fatigue now…. So word that differently, so you know, it's looking for them to say that it was only initially.

(Participant with RA: focus group three).

Questions were thus changed to emphasize that they were focussed on symptom onset, by including words such as ‘initially’ and ‘first began’ (see item 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8). Participants also advised that the questionnaire should be introduced by the statement ‘we would like to ask you about your thoughts and feelings at around the time you developed your arthritis'. In addition, they suggested that the headings to each section should make clear the timeframe that the questions related to. As a result, the following statement was added to the introduction to section 1: ‘These questions ask about your experience of symptoms before you first went to see your GP’, and similar headings were added to subsequent sections as appropriate.

Section 2: reactions to symptom onset

Psychological reactions to the presence of RA symptoms included ignoring symptoms, normalizing symptoms, carrying on as usual and a ‘wait and see’ approach. Participants believed that reactions like these caused people to delay for longer and should be a strong feature of the items in section 2.

My equivalent is the computer at work and I'd think of my shoulders and it happens to so many people….you think oh I have been spending too long on the computer, I ought to do my exercises, I will take some more painkillers so you are normalising it.

(Participant with RA: focus group four).

Section 3: initial self‐management of symptoms

Participants suggested that self‐management strategies caused people to delay for longer and should feature in the questionnaire, particularly as they may offer symptomatic relief but would not be of benefit to long‐term disease outcomes.

I don't know if you could add this, but some people try to keep moving, or try to sit better at their desk. So…. I certainly tried to do things for myself which involved trying to change my behaviour.

(Participant with RA: focus group one).

The range of self‐management strategies described during the focus groups was broad and varied.

The usual things are ‘oh I'll take some paracetamol’, I'll try an ice pack or a hot pack.

Oh heat pack is another thing that we can put on there.

Yeah like lavender.

Oh yeah those bean bags that you can put in the microwave.

I think a lot of people take cod liver oil, while it's good it's not going to do anything for something this major.

(Participants with RA: focus group three).

Items related to the use of over the counter medications, exercise, diet, seeking advice from pharmacists, complementary therapists, other types of health‐care professional and seeking spiritual or religious help were discussed. Participants highlighted that the items included in this section of the questionnaire should cover a range of possibilities including using pharmacies (items 16 & 18), alternative medicines (item 21) and baths (item 27).

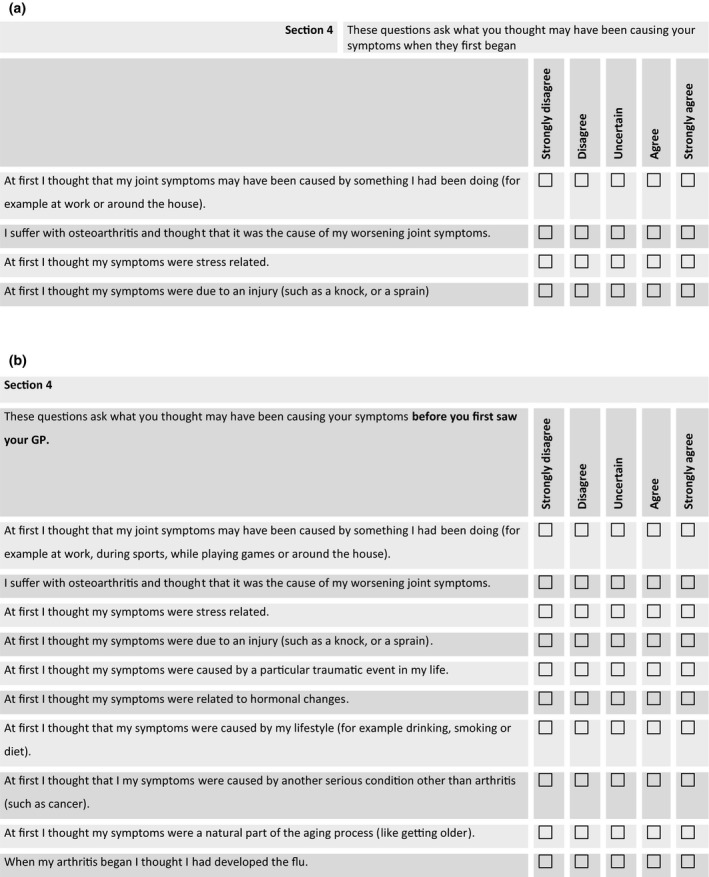

Section 4: beliefs about the causes of symptoms

Participants discussed the causes they had attributed the early symptoms of RA to or had heard that other people had attributed the initial symptoms of RA to. The causes selected for the draft DELAY questionnaire related to beliefs about the causes of symptoms which may have influenced help‐seeking behaviour. Some participants suggested that the questionnaire should contain questions which related to the menopause; however, the group felt that this was a gender‐specific issue and concluded that statement which related to ‘hormone changes’ would be preferable (item 33).

RP 7: Say whether it would be too much of a leading question, should there be a question on the menopause?

PRP 3: I mean you could say, well not to natural causes, but to the menopause, or just generally getting old.

PRP 4: Or hormone levels changing.

(Participant with RA: focus group two).

Some participants questioned whether the questionnaire was relevant to younger people in its current form and whether it reflected the activities that younger people typically engage in.

Would you consider doing a section for younger people, I mean when you're younger you don't really do that much house work, so you can't really attribute it to getting down on the floor and scrubbing the carpet because you're a teenager and you don't really do that sort of thing. So I guess I would have attributed my symptoms to that, I would have attributed it to sport or something like that – if I was a sporty person. So there needs to be something along those lines for younger people. So that younger people feel involved in the questions and that

(Participant with RA: focus group three).

In response to this, careful consideration was given to the relevance of items to all age groups. Some items were changed for example playing games was included in the following question, ‘At first I thought that my joint symptoms may have been caused by something I had been doing (for example at work, during sports, while playing games or around the house)’ (item 28).

Figure 1 illustrates the impact of participant involvement on saturating one section of the questionnaire with a range of perspectives on causal beliefs and how they may influence patient delay.

Figure 1.

Section 4 before (a) and after (b) input from Research Partners.

Section 5: speaking to other people and seeking information

Participants highlighted the positive and negative consequences of speaking to other people about symptoms. In some cases, interactions were felt to delay help‐seeking behaviour.

And, so probably it had been 2 or 3 weeks like that I had spoken to a friend and they said ‘Oh yes…..you expect to get stiffness and aches and pains’. And my ankles my feet were a bit….. were painful.

(Participant with RA: focus group four)

In addition, it was felt that the internet was also used to find information about symptoms, diagnoses and treatment. Therefore, the internet was seen as an alternative to asking other people for information before seeking help. The group highlighted that information obtained, for example via the internet or by speaking with others, could lead a person to seek help or could cause them to delay for longer and that questionnaire items should reflect both circumstances (see items 41 & 42).

So it is another tool that they use, but it can have a negative impact. So an important question maybe if they search for information on the internet did it stop them going to see their GP. Because they may have pulled up methotrexate and thought, ‘oh I ain't going’. If that's what I've got, then I not going…… going down that path.

(Participant with RA: focus group three).

Section 6: knowledge

Participants highlighted that many people were unaware that there was more than one type of arthritis and may never have heard of RA.

There are people in my family that have or had osteoarthritis but some might have RA. In clinic I was asked if there was a family history and I said no but looking back there probably were people in my family with RA.

(Participant with RA: focus group five).

Additional items were added to the questionnaire to explore the knowledge that participants felt the public had about RA, and the type of knowledge that may help a member of the public to be aware of RA and seek prompt help at the onset of symptoms.

Section 7: direct barriers and drivers of help seeking

Participants were encouraged to reflect on additional questions and items to be added to the questionnaire. Not being able to carry out everyday activities and the increasing severity of symptoms were thought to encourage help seeking.

I think some of them do keep trying to go [to the GP], and it affects them quite severely, and there may be a reason for them presenting. Because they couldn't go to the gym and couldn't do the five a side football. Or whatever.

(Participant with RA: focus group five).

A question was added about not being able to perform daily activities (item 55). In addition to this, three questions were added about the severity of pain (item 56), stiffness (item 57) and swelling (item 58).

Participants recognized that in some cases, people sought help for very different reasons. Participants felt that in some cases, people may have been motivated to see the GP for an explanation of symptoms, while others may have been driven by the desire for symptom relief. Therefore, items 59 to 62 reflected the different reasons participants felt would drive someone at the onset of symptoms to help‐seeking behaviour.

Because you know that there is something really wrong. (Interviewer: ‘Was that more important than getting treatment?’). ‘Yeah, because you fearing what it's going to lead to, I mean am I going to be a cripple for the rest of my life?’

(Participant with RA: focus group three).

Participants suggested that people with busy lives would be less likely to seek help; therefore, a direct barrier to seeking help was a lack of time. This theme was reflected in item 62.

I think an overriding factor is that people don't have the time. People who are employed are running round like, not headless chickens, but the last thing that they worry about is their health because they are more interested in earning a living to feed the children and run the car and so on and so I think the time factor is the enemy of you getting information across to people.

(Participant relative of person with RA: focus group one).

Section 8: communicating with health‐care professionals

Participants described how some patients did not like visiting their GP; reasons were varied including finding it difficult to communicate with the GP and not wanting to waste the GP's time.

But I think a lot depends on the relationship with the GP. The patient's belief in their GP. So, some patients may be aware that they are viewed as a malingerer, and this may impact on their future help‐seeking behaviour.

(Participant with RA: focus group four)

In addition, it was highlighted that primary care was seen by some as a pressured emergency service not appropriate for musculoskeletal complaints. In contrast, it was recognized that some individuals were ‘demanding’ in their approach to health‐care and were thus more likely to seek help quickly.

Getting back to the doctors, if it's not in your nature to be demanding, you know, it's finding the right words to say to them.

(Participant with RA: focus group three).

It was generally felt that some people had a dislike of doctors and thus did not like to visit their GP, while other people did not want to bother or inconvenience the doctor.

I mean question two ‘I won't go to see the doctor if I think I can control it myself’. I think 90% of people would rather do it themselves rather than trouble the doctor.

(Participant with RA: focus group five).

Focus groups with Health‐care professionals

Health‐care professionals were asked to reflect on their experiences of patients consulting with the early symptoms of RA and consider how their experiences mapped on to questionnaire items. The quotations below are examples of the experiences health‐care professionals recalled.

One of my patients recently, a new RA he had it for about 3 or 4 months and he got it in his feet. And what he would do every morning is he'd wake up extra early and take is dog out for a walk, an extra along walk and the walk got longer and longer and longer, because he said that when he walked his feet felt better. So he just carried on and you know.

(Consultant rheumatologist)

The last one I had, had a mother with Rheumatoid. But she had delayed coming because she had a lot of other co‐morbidities. She had depression. And she had family troubles.

(Rheumatology specialist nurse)

Health‐care professionals confirmed that the items in the questionnaire were representative of their experiences. They also confirmed and discussed the organization of items into sections and felt that these sections represented core and overarching drivers of patient delay.

You've got a section on lay sources of information, the internet, the Daily Mail and sources like that. Definitely the internet. Like the health columns in the newspaper.

(Practice nurse)

In addition, health‐care professionals recommended three items to be added to the pool generated during the previous focus groups with patients and relatives (see items, 25, 30 and 50).

Just general relaxation, mild exercises and just try to take it easy, but it's not really captured, we could write a question about yoga, massage or relaxation people talk about Pilates.

(Consultant rheumatologist)

I will add another one, ‘I think that my condition is stress related’. I see patients that think it's work related here's another one for you.

(Practice nurse)

The question would be if you think there is a magic cure for something called RA, would you have come earlier. As you have said, most people don't realise that there is a magic cure out there………Maybe you could say….’I didn't think that there was treatment available’. Or a treatment that needed to be given early.

(General practitioner)

Finally, health‐care professionals commented upon the language used in the questionnaire. Health‐care professional was concerned that some items may be difficult for patients to understand and therefore prone to misinterpretation. Item 11 was changed, and the word ‘circumstance’ was replaced with ‘etc’ following the statement below.

It's just language I mean the first page someone of my age, gender and circumstances. I mean age everyone understands, gender ‐ does everyone know what that means?, well… circumstance what does that mean? To some people that make sense but to our patients it wouldn't make sense.

(Nurse consultant)

Test–retest findings

A total of 91 patients were approached to participate, of whom 69 consented and completed baseline questionnaires. Forty‐one of these patients completed the follow‐up questionnaire. The characteristics of responders are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

demographic characteristics of patients consenting to participate in the test–retest study

| Baseline (N = 69) | Follow‐up (N = 41) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) |

Mean: 53.8 SD: 14.6 |

Mean: 51.1 SD: 15.2 |

| Female; n (%) | 50 (72.5) | 29 (70.7) |

| Ethnic origin; n (%) | ||

| White British | 60 (87.0) | 37 (90.2) |

| South Asian or South Asian British | 6 (8.7) | 3 (7.3) |

| Black British | 3 (4.3) | 1 (2.4) |

| Time from symptom onset to initial contact with health‐care professionala |

Median: 49 days IQR: 2–153 days |

Median: 41 days IQR: 7–153 days |

| Fulfilment of 2010 ACR/ EULAR classification criteria for RA; n (%) | 40 (58.0) | 29 (70.7) |

| Disease activity score 28 |

Mean: 4.7 SD: 1.4 |

Mean: 4.3 SD: 0.9 |

Median reported due to data not being normally distributed.

Intraclass correlations indicated that the majority of questionnaire items showed good reliability over time. Table 1 shows the intraclass correlations and significance level of each item. Seven questionnaire items (20, 23, 25, 40, 41, 46 and 61) were deleted due to weak intraclass correlations which did not reach a predetermined level of significance of < 0.01.

Discussion

We have adopted a mixed approach to the development of the DELAY questionnaire, a tool to assess the drivers of and barriers to patient consultation at the onset of RA. This study, like others, has demonstrated that people with RA, relatives and carers have a valuable role to play in the development of research instruments.27, 32 We have described aspects of face and content validity and test–retest reliability and how these were assessed through qualitative methods and statistical testing. Participants (including people with the lived experience of RA and health‐care professionals) have impacted on questionnaire design by adding questions to the item pool, modifying phraseology, determining item relevance and organizing statements for the questionnaire into eight sections, thus directly influencing questionnaire format. Fatigue has previously been recognized by patients as a key attribute for patient reported outcome measures for RA.20 Our study adds to this by suggesting that fatigue is an important determinant of help‐seeking behaviour – the use of this questionnaire in prospective studies will assess the extent to which this is so.

The aim of the questionnaire development process was to generate a large pool of potential reasons for patient delay at the onset of RA, and the next phase of this research is to attempt to quantify the occurrence of these reasons for delay in a large cohort of people with a new onset of RA symptoms. Our current research is using the DELAY questionnaire in a cross‐sectional sample of people with RA and unclassified arthritis. This questionnaire is used alongside a questionnaire completed by a health‐care professional in secondary care (rheumatologist or nurse specialist) during the initial contact with the patient. The health‐care professional questionnaire captures data on a range of demographic, socioeconomic and disease‐related variables as well as the extent of delay at different time points in the patient's journey from symptom onset to rheumatology assessment. In particular, delays from the onset of symptoms of inflammatory arthritis and from the onset of persistent joint swelling are captured, in line with recent recommendations from the EULAR study group for risk factors for RA.33 Relationships between patients’ perspectives on their disease and their responses to statements reflecting reasons why they may present quickly or slowly will be related to the extents of delay in seeking help to understand in detail the correlates of rapid and delayed help seeking.

The DELAY study is on‐going, and exploratory factor analysis is planned to identify clusters of items which may explain different types of help‐seeking behaviour and validation and testing in other languages. This is particularly pertinent, as recent data indicate that people from South Asian communities delay for longer in seeking help at the onset of RA.13 Translations of this tool, if validated and reliability tested using the methodology presented in this study, can be used to understand the barriers specific to other communities. In some countries including the UK, only half of patients present to a health‐care professional within 12 weeks of the onset of symptoms attributable to their RA.11 However, in other countries including Austria, Germany and the Netherlands, delay on the part of the patient is shorter.2, 11 The DELAY questionnaire with validation for use in other countries could be used to explore such international differences in reasons for patient delay.

Lengthy patient delays in seeking help are seen in many other musculoskeletal diseases besides RA, and in some situations (e.g. patients with ankylosing spondylitis), it is much longer than in RA.34 As in RA, long patient delays can lead to poor patient outcomes.35 The DELAY questionnaire provides a template which can be adapted to better understand patient delay in other musculoskeletal conditions, where early intervention is beneficial to patients.

Conclusion

In collaboration with patients, relatives and a multidisciplinary team of health‐care professionals, we have developed and tested a questionnaire to explore patient delay in help seeking for RA. Involvement of people with the lived experience of arthritis in the development of this research tool has led to a more patient oriented measure which includes items of most relevance to RA patients’ experiences and in a format that is acceptable for completion. After statistical testing and further feedback from patients, the DELAY questionnaire is now being administered in a cross‐sectional study to investigate the causes of delay and drivers of help seeking in different demographic groups. Data from this study will inform the development of tailored health promotion interventions targeted at reducing delay in help seeking for patients with new onset RA.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the Research for Patient Benefit Programme (funder's reference PB‐PG‐1208‐18114). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the DELAY study service user panel and all of the patients and health‐care professionals who continue to support the study. We would also like to thank Birmingham Arthritis Resource Centre and the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Network, for their on‐going support and partnership. Finally, this multicentre study has benefited from the support of the Research and Development department at Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS trust.

Appendix 1. DELAY Pilot Study Syndicate

Professor Christopher Buckley, Dr Mary Gayed, Dr Karl Grindulis, Dr Sabrina Kapoor; Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust. Dr. Sarah Westlake and Julia Taylor; Poole Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Tanya Potter; University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust. Dr. Marwan Bukahri and Bronwen Evans; University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust. Francesca Leon; St Georges Healthcare NHS Trust. Dr. Raad Makadsi and Stephanie Allen; Surrey and Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust.

References

- 1. Raza K, Buckley CE, Salmon M, Buckley CD. Treating very early rheumatoid arthritis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 2006; 20: 849–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Linden MP, le Cessie S, Raza K et al Long‐term impact of delay in assessment of early arthritis patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 2010; 62: 3537–3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nell VP, Machold KP, Eberl G, Stamm TA, Uffmann M, Smolen JS. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2004; 43: 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott DL, Hunter J, Deighton C, Scott DG, Isenberg D. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis is good medicine. British Medical Journal, 2011; 343: d6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feldman DE, Bernatsky S, Haggerty J et al Delay in consultation with specialists for persons with suspected new‐onset rheumatoid arthritis: a population‐based study. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 2007; 57: 1419–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kiely P, Williams R, Walsh D, Young A. Contemporary patterns of care and disease activity outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis: the ERAN cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2009; 48: 57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kumar K, Daley E, Carruthers DM et al Delay in presentation to primary care physicians is the main reason why patients with rheumatoid arthritis are seen late by rheumatologists. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2007; 46: 1438–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oliver S, Bosworth A, Airoldi M et al Exploring the healthcare journey of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a mapping project ‐ implications for practice. Musculoskeletal Care, 2008; 6: 247–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villeneuve E, Nam JL, Bell MJ et al A systematic literature review of strategies promoting early referral and reducing delays in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2012; 27: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sandhu RS, Treharne GJ, Justice EA et al Comment on: delay in presentation to primary care physicians is the main reason why patients with rheumatoid arthritis are seen late by rheumatologists. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2008; 47: 559–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raza K, Stack R, Kumar K et al Delays in assessment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: variations across Europe. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2011; 70: 1822–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Nies JA, Brouwer E, de Rooy DP et al Reasons for medical help‐seeking behaviour of patients with recent‐onset arthralgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2012; 6: 1302–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kumar K, Daley E, Khattak F, Buckley CD, Raza K. The influence of ethnicity on the extent of, and reasons underlying, delay in general practitioner consultation in patients with RA. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2010; 49: 1005–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sheppard J, Kumar K, Buckley CD, Shaw KL, Raza K. ‘I just thought it was normal aches and pains’: a qualitative study of decision‐making processes in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2008; 47: 1577–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stack RJ, Shaw K, Mallen C, Herron‐Marx S, Horne R, Raza K. Delays in help seeking at the onset of the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2012; 71: 493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Townsend A, Wyke S, Hunt K. Self‐managing and managing self: practical and moral dilemmas in accounts of living with chronic illness. Chronic Illness, 2006; 2: 185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cameron L, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Symptom representations and affect as determinants of care seeking in a community‐dwelling, adult sample population. Health Psychology, 1993; 12: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bishop GD, Converse SA. Illness representations: a prototype approach. Health Psychology, 1986; 5: 95–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stack RJ, Shani M, Mallen CD, Raza K. Symptom complexes at the earliest phases of rheumatoid arthritis: a synthesis of the qualitative literature. Arthritis Care Research, 2013; 65: 1916–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A et al Patient perspective: fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology, 2007; 34: 1174–1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirwan JR, Hewlett S. Patient perspective: reasons and methods for measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology, 2007; 34: 1171–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirwan JR, Ahlmen M, de WM et al Progress since OMERACT 6 on including patient perspective in rheumatoid arthritis outcome assessment. Journal of Rheumatology, 2005; 32: 2246–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. Patient perspective of measuring treatment efficacy: the rheumatoid arthritis patient priorities for pharmacologic interventions outcomes. Arthritis Care Research (Hoboken), 2010; 62: 647–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C et al Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expectations, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1369‐7625.2012.00795.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barber R, Boote JD, Cooper CL. Involving consumers successfully in NHS research: a national survey. Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 380–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mahoney CA, Thombs DL, Howe CZ. The art and science of scale development in health education research. Health Education Research, 1995; 10: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Staley K. Exploring Impact Study: Public Involvement in NHS, Public Health and Social Care Research. Eastleigh: INVOLVE, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. McColl E, Jacoby A, Thomas L et al Design and use of questionnaires: a review of best practice applicable to surveys of health service staff and patients. Health Technology Assessment, 2001; 5: 1–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guest GS, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30. QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, version 8 [computer program]. Victoria, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2010; 69: 1580–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pugh W, Porter AM. How sharp can a screening tool be? A qualitative study of patients’ experience of completing a bowel cancer screening questionnaire. Health Expectations, 2011; 14: 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gerlag DM, Raza K, van Baarsen LG et al EULAR recommendations for terminology and research in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis: report from the Study Group for Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2012; 71: 638–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamilton L, Gilbert A, Skerrett J, Dickinson S, Gaffney K. Services for people with ankylosing spondylitis in the UK–a survey of rheumatologists and patients. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2011; 50: 1991–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tillett W, Jadon D, Shaddick G et al Smoking and delay to diagnosis are associated with poorer functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 2013; 72: 1358–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]