Abstract

Background

A high‐quality decision for breast cancer surgery requires that patients are well informed, meaningfully involved in decision making, and receive treatments that match their goals. There is little in the existing literature that examines a comprehensive measure of decision quality for Latina breast cancer patients.

Objective

To examine the quality of surgical decisions among Latina breast cancer survivors and explore factors associated with decision quality and decision regret.

Design

Cross‐sectional mailed survey.

Main outcome measures

English and certified Spanish translations of Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument (BCS‐DQI), Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) and decision regret.

Participants and setting

Ninety‐seven breast cancer survivors of Hispanic or Spanish descent identified through the cancer registry from Orange or San Diego Counties in California.

Results

The 97 respondents were on average 55.7 years old, 39.1% had high school diploma or more education, and 62.9% had low acculturation (SASH scores < 2.99). The average knowledge score was 48.2%, the average decision process score was 67.5%, and many (77.3%) received treatments that matched their goals. In multivariable models, there were no significant associations with education, age, acculturation and any aspect of decision quality or decision regret in this sample. Respondents who had higher decision process scores, indicating more involvement in decision making, had significantly lower decision regret.

Conclusions

The BCS‐DQI may require some adaptation for Latina populations to improve acceptability. The different aspects of decision quality, including knowledge, decision process and concordance, did not vary by level of acculturation.

Keywords: decision quality, shared decision making

Introduction

Patients with breast cancer face challenging decisions about treatment. Most patients are able to choose either lumpectomy or mastectomy for surgical treatment, and this decision requires patients to understand what is involved with the different procedures, including the potential impact on cosmetic results, chance of cancer recurrence and survival. Patients feel differently about keeping or losing their breast and about the prospect of local recurrence, so tailoring treatments to patients' goals is important.1 To understand decision quality for breast cancer surgery, it is important to assess the extent to which patients are well informed, meaningfully engaged in the decision‐making process, and receive treatments that match their goals and concerns.2, 3

A few studies have attempted to measure decision quality as defined above. Lee et al.3 found that patients treated at four academic cancer centres reported relatively low knowledge, moderate involvement and a high percentage received treatments that matched their goals. Collins et al. 1 reported on a sample of patients with breast cancer at one academic centre, all of whom had received a patient decision aid, who had high knowledge and a high percentage of patients receiving treatments that matched their goals. These studies provide some insight into a comprehensive assessment of decision quality, yet the samples had very limited diversity and as a result limited generalizability.

It is not clear whether this approach to measuring decision quality makes sense across cultures. Latina culture tends to be more family centred than American culture, and Latinas tend to be more deferential towards physicians.4, 5 One study suggests that Latina patients are more satisfied when they receive a recommendation from the physician.6 There is other research that suggests there are variations in involvement regarding treatment decisions and in decision satisfaction among Latina and non‐Latina breast cancer patients based on acculturation and health literacy.7 Acculturation is a process by which a minority group adopts and adapts to the norms, values and attitudes of the mainstream through increased contact with a new nation or culture.8

The purpose of this article is to examine the decision quality for surgical treatment of breast cancer among Latina patients, specifically their knowledge about breast cancer, whether they receive treatments that match their goals, and the nature of the interactions with their health‐care providers. We then explore whether factors, including age, education and acculturation, are associated with decision quality and decision regret.

Methods

Patient sample recruitment

Patients by Spanish surname were identified through the California Cancer Registry (CCR), and their eligibility was determined by screening medical record information. Eligible patients were Hispanic or of Spanish descent (as confirmed on survey), 21 years of age and older, and diagnosed with early stage breast cancer (Stage 1 or 2) in Orange or San Diego County in 2009–2010. Exclusion criteria included having bilateral breast cancer and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, as these conditions impact the surgical decision.

Study protocol/design

The patients' physicians received a letter to notify them of the intent to contact their patient and were given 2 weeks to opt their patient out of the study. All eligible patients whose physician did not opt out received a cover letter (in English and Spanish), an information sheet in Spanish about the study, a copy of the survey in Spanish and a postage paid return envelope. The cover letter indicated that participants could contact staff to receive the survey in English if they preferred. The protocol was changed part way through the study to make it easier for participants to complete the survey in English. For the majority of potential participants (n = 207), all reminder mailings included both the English and Spanish version of the survey. Non‐respondents received a reminder phone call at 2 weeks and a reminder packet at 4 weeks. Responders received a small gift for completing the survey. Consent was implied by completion of the survey or given verbally over the phone to a member of the study staff. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at both Massachusetts General Hospital and at the University of California Irvine.

Due to multiple changes in study staff over the 1‐year project, a significant portion of patients received an initial mailing and then did not receive a phone reminder or reminder mailing at the scheduled intervals. About 2/3rds of potential participants received the phone reminder at 6–8 weeks after and the mailed reminder at 8 weeks or more after the initial mailing.

Translation and pilot testing

All of the measures were translated into Spanish and certified by translation services at the University of California Irvine.

We piloted the survey and study protocol with 22 Hispanic breast cancer patients identified through the registry who met the study eligibility criteria. We had 16 of 22 (72.7%) response rate and found most questions were acceptable. Several of the knowledge questions (seven of 12) had more than 5% missing data (range 6.3–31.3%). Despite a high rate of missing responses, we did not include a response option of ‘not sure’ for the knowledge items. This decision was based on experience in the prior field test where a large portion of respondents selected that option (30–40% for several items), which resulted in very low knowledge scores because a response of ‘not sure’ was scored as incorrect. In debriefing interviews with participants in that prior field test, it was apparent that participants did know more than their knowledge scores indicated. We felt that removing that response option would provide a better measure of the respondents knowledge and was worth the potential increase in missing responses. We did assume that a missing response indicated a lack of knowledge so it was considered incorrect. In fact, several respondents in the pilot study wrote in ‘don't know’ or ‘?’on the survey when skipping an item. None of the respondents in the pilot study skipped more than half of the knowledge items.

Two of the goals (how important is it to keep your breast & how important is it to remove your breast to gain peace of mind) required some revisions. Six respondents had selected 10 out of 10 (or extremely important) for both of these items in the pilot surveys. Revisions were made to improve comprehension and distinguish these two items. We then conducted cognitive interviews with three additional Latina breast cancer survivors. All three were able to describe how the two items were different without any problems, so no further changes were made.

Measures

Patient demographics (age, race/ethnicity, education, treatments) were self‐reported. We also collected information about date of diagnosis, stage of disease and treatments from the California Cancer Registry.

Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics

The Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH) consists of 12 items each ranging from 1 to 5 with higher numbers indicating use of more English and/or spending more time with non‐Latinos. A total score ranges from 0 to 5 and is calculated taking the average of the 12 items. Higher scores indicate a higher level of acculturation, and a cut‐off at 2.99 distinguishes a population that is less acculturated (<2.99) and more acculturated (≥2.99).8 The SASH score has been shown to have high reliability (alpha coefficient 0.92) and good validity, for example, highly correlated with length of time in country.8, 9

Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument

The Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument (BCS‐DQI) has three sets of items and results in three scores. The knowledge and concordance scores have been shown to have good retest reliability, discriminant validity and acceptability2, and the decision process score also has demonstrated good internal consistency, retest reliability, validity and acceptability3 in a largely White sample of patients with breast cancer.

Knowledge score: The 10 multiple choice and two open‐ended knowledge items were scored (correct/incorrect), and a total knowledge score from 0 to 100% was calculated by dividing the number of correct responses by the number of items and multiplying by 100. Missing responses were considered incorrect, and a total knowledge score was calculated for all respondents who answered at least half of the questions.

Concordance score: Three goals were rated on an importance scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (extremely important). One question assessed their preferred surgical treatment. We calculated the percentage of patients who received treatments that matched their goals using the model generated in Sepucha et al.2 The regression model generated a predicted probability of mastectomy for each patient based on their goals. Patients with a predicted probability of more than 0.5 who had mastectomy or those with a predicted probability of 0.5 or less who did not have mastectomy were classified as having treatments that ‘matched’ their goals. This yielded a summary concordance score that ranged from 0 to 100%, indicating the percentage of patients whose treatment choice ‘matched’ their goals. Higher scores indicate that more patients received treatments that matched their goals.

Decision process score: Seven items assessed the (i) discussion of options (yes/no), (ii) amount of discussion of pros (a lot/some/a little/not at all), (iii) amount of discussion of cons (a lot/some/a little/not at all) and (iv) discussion of patients' goals and treatment preferences (yes/no). Each item with a response of ‘yes’ or ‘a lot/some’ received one point, and all other responses received no points. A total decision process score was calculated by summing the points, dividing by seven, and multiplying by 100, resulting in scores from 0 to 100% with higher scores indicating more shared decision making. The seven decision process items had good reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.77) in this sample.

Decision regret

One item assessed whether patients would choose the same type of surgery with responses: definitely have the same type, probably have the same type, not sure, probably not have the same type and definitely not have the same type.

Statistical analysis

We calculated a response rate and examined descriptive statistics for sample demographics and all variables. We compared patient characteristics for those with high and low acculturation using two‐sided t‐tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi‐square tests for categorical variables.

Acceptability of the survey was examined using length of time to complete the instrument, which was self‐reported by patients, and response rates. Feasibility was examined using rates of missing data; any item with more than 5% of responses missing was considered problematic (e.g. missing or incorrect responses).

We examined the following hypotheses:

Acculturation will be associated with decision quality scores; specifically, respondents with high‐acculturation scores will have higher knowledge scores, higher decision process scores and a higher percentage of concordant care compared with those with low‐acculturation scores. To test these hypotheses, we created two multivariable linear regression models to examine factors associated with knowledge scores and decision process scores and one multivariable logistic regression model to examine factors associated with concordance. The pre‐specified factors included acculturation score, age, education and final surgical treatment received (i.e. either mastectomy or lumpectomy) for each model.

Respondents with poor decision quality (low knowledge, limited decision process and no concordance) will have more decision regret than those with high decision quality.

To test this hypothesis, we developed a multivariable logistic regression model of regret that examined the following factors: surgical treatment received, knowledge score, decision process score, concordance score and acculturation score.

Analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS version 9.3 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Response rates and sample

Overall, 116 of 274 patients (response rate: 42%) completed the survey. Nineteen of these respondents were deemed ineligible after completing the survey (four were not stage 1 or 2, 5 had Spanish surname only, and 10 did not self‐report their ethnicity on the survey), and the analyses were conducted on the remaining 97 eligible Latina respondents. Patients were on average 55.7 years of age (SD 11.3 years), 77.3% were white and 80.4% identified self as Mexican‐American, 11.3% as Central American, 7.2% as South American and 1% as Puerto Rican/Cuban/Dominican. Sixty respondents (62%) completed the survey in Spanish, and 37 respondents (38%) completed the survey in English. In the sample, 62.9% of respondents had low‐acculturation scores (<2.99) and 37.1% had high‐acculturation scores (≥2.99). The average acculturation score for all respondents was 2.54 (SD 1.24), and scores ranged from 0.90 to 5.00.

The patient sample demographics are provided in Table 1. Several factors did vary by acculturation score, as respondents with high acculturation were more likely to have lumpectomy as their surgery type, more likely to have high school education or greater, be working full‐time, have higher income, and have lived longer in the United States.

Table 1.

Patient demographics by level of acculturation

| All N = 97 | SASH < 2.99 N = 61 (62.9%) | SASH ≥ 2.99 N = 36 (37.1%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.7 (11.3) | 54.9 (10.6) | 57.0 (12.4) | 0.41 |

| Stage | ||||

| Stage 1 | 53 (54.6%) | 34 (55.7%) | 19 (52.8%) | 0.78 |

| Stage 2 | 44 (45.4%) | 27 (44.3%) | 17 (47.2%) | |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Lumpectomy | 53 (54.6%) | 26 (42.6%) | 27 (75%) | 0.002 |

| Mastectomy | 44 (45.4%) | 35 (57.4%) | 9 (25%) | |

| Other treatments | ||||

| Radiation | 58 (59.8%) | 34 (55.7%) | 24 (66.7%) | 0.29 |

| Chemotherapy | 53 (54.6%) | 33 (54.1%) | 20 (55.6%) | 0.89 |

| Hormone therapy | 48 (49.5%) | 26 (42.6%) | 22 (61.1%) | 0.15 |

| Months since diagnosis (median, Q1, Q3) | 28 (24, 40.0) | 28 (23.0, 35.0) | 27.5 (24.5, 40.0) | 0.89 |

| Race | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 75 (77.3%) | 46 (75.4%) | 29 (80.6%) | 0.60 |

| Non‐white | 4 (4.1%) | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (5.6%) | |

| Not answered | 18 (18.6%) | 13 (21.3%) | 5 (13.9%) | |

| Education | ||||

| ≤8th grade | 28 (28.9%) | 25 (41%) | 3 (8.3%) | 0.0005 |

| High school | 29 (29.9%) | 18 (29.5%) | 11 (30.6%) | |

| >High school | 38 (39.2%) | 16 (26.2%) | 22 (61.1%) | |

| Not answered | 2 (2.1%) | 2 (3.3%) | 0 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/committed relationship | 60 (61.9%) | 41 (67.2%) | 19 (52.8%) | 0.16 |

| Single/divorced/separated/widowed | 37 (38.1%) | 20 (32.8%) | 17 (47.2%) | |

| Employment status now | ||||

| Working full time | 25 (25.8%) | 11 (18%) | 14 (38.9%) | 0.047 |

| Working part time | 11 (11.3%) | 6 (9.8%) | 5 (13.9%) | |

| Not working | 60 (61.9%) | 43 (70.5%) | 17 (47.2%) | |

| Not answered | 1 (1%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 | |

| Income | ||||

| ≤$30 000 | 49 (50.5%) | 38 (62.3%) | 11 (30.6%) | 0.002 |

| $30 001–60 000 | 21 (21.6%) | 9 (14.8%) | 12 (33.3%) | |

| >$60 000 | 16 (16.5%) | 6 (9.8%) | 10 (27.8%) | |

| Not answered | 11 (11.3%) | 8 (13.1%) | 3 (8.3%) | |

| Years in the USA, mean (SD) | 35.0 (17.3) | 26.7 (12.5) | 49.2 (15.0) | <0.0001 |

SASH, Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics.

Acceptability and feasibility

The response rate of 42% was much lower than the pilot test response rate (72.7%). Respondents reported taking an average of 26.9 min (range 10–120 min) to complete the entire survey, and timing did not vary between those who completed the survey in English or in Spanish (27.8 min vs. 26.3 min P = 0.68). As expected from the pilot, there was a considerable amount of missing data for the knowledge items (mean 13.6%, with range 1–29.9%), and nine of twelve items had more than 5% missing. Of the 97 respondents, 7 (7.2%) did not receive a total knowledge score because they did not answer more than half of the knowledge questions. We found few missing responses among the seven decision process items (mean 1% with range 0–2%) and the five goal questions (mean 0.5% with range 0–1%).

Knowledge of treatments and outcomes

The mean total knowledge score was 48.2% (SD 15.4%). Table 2 includes a subset of the knowledge items and correct responses. More than half (56.7%) of respondents incorrectly believed that waiting 4 weeks to make a decision about treatment would have a big impact on survival. Most (72.2%) correctly responded that with treatment, most women will die of something other than breast cancer. A little more than half (58.8%) knew that survival was the same with either mastectomy or lumpectomy. Few (35.1%) knew that women who had a lumpectomy and radiation had a higher chance of cancer recurring in the breast that had been treated.

Table 2.

English version of selected knowledge items and responses by level of acculturation

| Item | All (N = 97) (%) | Low acculturation (N = 61) (%) | High acculturation (N = 36) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| For most women with early breast cancer, how much would waiting several weeks to make a treatment decision affect their chances of survival? | |||

| A lot | 55 (56.7) | 43 (70.5) | 12 (33.3) |

| Somewhat | 22 (22.7) | 9 (14.8) | 13 (36.1) |

| aA little or not at all | 19 (19.6) | 9 (14.8) | 10 (27.8) |

| Missing | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (2.8) |

| With treatment, about how many women diagnosed with early breast cancer will eventually die of breast cancer? | |||

| Most will die of breast cancer | 3 (3.1) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| About half will die of breast cancer | 13 (13.4) | 6 (9.8) | 7 (19.4) |

| aMost will die of something else | 70 (72.2) | 46 (75.4) | 24 (66.7) |

| Missing | 11 (11.3) | 7 (11.5) | 4 (11.1) |

| After which treatment is it more likely that women will need to have another operation to remove the tumour? | |||

| aLumpectomy | 42 (43.3) | 21 (34.4) | 21 (58.3) |

| Mastectomy | 10 (10.3) | 8 (13.1) | 2 (5.6) |

| Equally likely for both | 38 (39.2) | 26 (42.6) | 12 (33.3) |

| Missing | 7 (7.2) | 6 (9.8) | 1 (2.8) |

| On average, which women with early breast cancer live longer? | |||

| Women who have a mastectomy | 23 (23.7) | 14 (23) | 9 (25) |

| Women who have a lumpectomy and radiation | 8 (8.2) | 6 (9.8) | 2 (5.6) |

| aThere is no difference | 57 (58.8) | 35 (57.4) | 22 (61.1) |

| Missing | 9 (9.3) | 6 (9.8) | 3 (8.3) |

| On average, which women have a higher chance of having cancer come back in the breast that has been treated? | |||

| Women who have a mastectomy | 3 (3.1) | 3 (4.9) | 0 |

| aWomen who have a lumpectomy and radiation | 34 (35.1) | 20 (32.8) | 14 (38.9) |

| There is no difference | 49 (50.5) | 30 (49.2) | 19 (52.8) |

| Missing | 11 (11.3) | 8 (13.1) | 3 (8.3) |

Indicates the correct answer.

In the univariate analyses, there were no significant differences in patients' total knowledge scores by age, education, final surgery received or acculturation. In the multivariable regression model, the relationship between acculturation score and total knowledge score was not significant after controlling for age, education and final surgery received (see Table 3A). In fact, none of the factors explained much of the variation in total knowledge score (Model R 2 = 0.05).

Table 3.

Multivariable regression models examining whether acculturation is associated with knowledge scores, decision process scores and concordance scores

| (A) Knowledge score linear regression results (N = 87) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Lower CL | Upper CL | P value |

| Intercept | 57.62 | 39.93 | 75.30 | <0.001 |

| Acculturation Score | ||||

| <2.99 | −1.38 | −9.08 | 6.33 | 0.73 |

| ≥2.99 | 0.00 | |||

| Agea | −1.72 | −4.72 | 1.27 | 0.26 |

| Surgical treatment | ||||

| Lumpectomy | 4.52 | −2.82 | 11.86 | 0.23 |

| Mastectomy | 0.00 | |||

| Education | ||||

| ≤8th grade | −1.74 | −10.71 | 7.24 | 0.71 |

| High school | −2.73 | −10.87 | 5.41 | 0.51 |

| >High School | 0.00 | |||

| (B) Decision Process Score linear regression results (N = 93) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Lower CL | Upper CL | P value |

| Intercept | 71.73 | 38.33 | 105.13 | <0.001 |

| Acculturation Score | ||||

| <2.99 | 9.87 | −4.67 | 24.40 | 0.19 |

| ≥2.99 | 0.00 | |||

| Agea | −1.81 | −7.38 | 3.76 | 0.53 |

| Surgical treatment | ||||

| Lumpectomy | 8.20 | −5.29 | 21.68 | 0.24 |

| Mastectomy | 0.00 | |||

| Education | ||||

| ≤8th grade | −4.16 | −20.76 | 12.44 | 0.62 |

| High school | −10.86 | −26.10 | 4.39 | 0.17 |

| >High School | 0.00 | |||

| (C) Concordance logistic regression results (N = 93) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | OR estimate | Lower CL | Upper CL | P value |

| Acculturation Score | ||||

| <2.99 | 1.34 | 0.43 | 4.25 | 0.62 |

| ≥2.99 | Ref | |||

| Agea | 1.57 | 0.98 | 2.52 | 0.06 |

| Surgical treatment | ||||

| Mastectomy | 1.81 | 0.57 | 5.76 | 0.32 |

| Lumpectomy | Ref | |||

| Education | ||||

| ≤8th grade | 1.11 | 0.26 | 4.78 | 0.89 |

| High school | 0.38 | 0.11 | 1.29 | 0.12 |

| >High School | Ref | |||

Lower CL, lower confidence limit; Upper CL, upper confidence limit; OR, odds ratio.

Increment of 10.

Involvement in the decision‐making process

Mean decision process score was 67.5% (SD 30.1%). Most respondents (86.6%) reported that their doctors explained that they had choices. Many (68.4%) reported their doctors discussed both mastectomy and lumpectomy as options, while 13.7% reported just discussion of mastectomy and 13.7% reported just discussion of lumpectomy. Many (66.7%) also reported that their doctors asked them about their treatment preferences.

In univariate analyses, patients' decision process scores did not vary significantly by age, education, final surgery received or acculturation. In the multivariable model, none of the factors was significantly associated with decision process scores (see Table 3B), nor did they explain much of the variation in decision process (Model R 2 = 0.06).

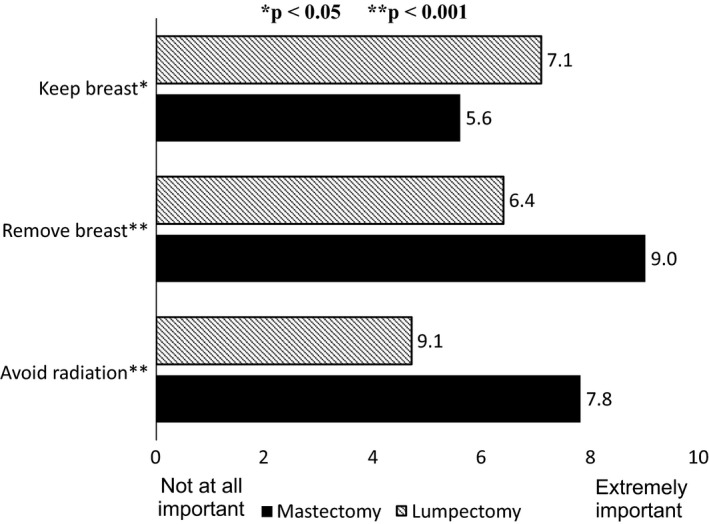

Preferences and goals for treatment

Patients who had a mastectomy rated their goals differently than patients who had a lumpectomy (see Fig. 1). As per Sepucha et al.,2 three goals and cancer stage were used in the concordance model, patients' desire to keep their breast, remove their breast for peace of mind and avoid radiation. The majority of patients (77.3%) received treatments that matched that predicted by their goals. A similar percentage of patients who had mastectomy and patients who had lumpectomy received treatments that matched their goals (79.6 vs. 75.5%, P = 0.63, chi‐square test).

Figure 1.

Respondents' goals (Mean Score) by treatment used in the concordance model.

There was not a significant difference between concordance scores for those with high‐ and low‐acculturation scores (72.2 vs. 80.3%, P = 0.36, chi‐square test). However, patients with concordant care were slightly older than patients without concordant care (mean age 56.8 vs. 52.0, P = 0.04, two‐sided t‐test). In the univariate analyses, there were no significant differences between patients' concordance and their education or final surgery received (lumpectomy or mastectomy). In the multivariable concordance model, age remained the only significant factor associated with concordance (see Table 3C). The model had a modest c statistic = 0.71.

Decision regret

A little more than half of respondents (60.8%) would definitely have the same type of surgery again, indicating no regret. In univariate analyses, there were no significant differences between patients' decision regret and their age, education, final surgery received, acculturation or total knowledge scores. The total decision process scores were significantly higher among those who had no decision regret compared with those who had some decision regret [74.1% (SD 27.5%) vs. 57.1% (SD 31.3%), P = 0.008]. There was also a significant association between decision regret and concordance. Respondents who received treatment that matched their goals were about twice as likely to have no regret (63.6 vs. 32%, P = 0.008).

In the multivariable decision regret model, the decision process score remained significantly associated with regret, while acculturation and other factors, including concordance, were not (See Table 4). The model had a reasonable c statistic = 0.70.

Table 4.

Decision regret logistic regression model results (N = 87)

| Effect | OR estimate | Lower CL | Upper CL | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation Score | ||||

| <2.99 | 1.52 | 0.50 | 4.64 | 0.46 |

| ≥2.99 | Ref | |||

| Agea | 1.02 | 0.66 | 1.59 | 0.92 |

| Surgical treatment | ||||

| Mastectomy | 1.09 | 0.38 | 3.18 | 0.87 |

| Lumpectomy | Ref | |||

| Education | ||||

| ≤8th grade | 0.52 | 0.14 | 1.91 | 0.32 |

| High school | 1.15 | 0.36 | 3.60 | 0.81 |

| >High school | Ref | |||

| Total knowledge scorea | 0.91 | 0.67 | 1.25 | 0.57 |

| Decision process scorea | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.98 | 0.03 |

| Concordance | 0.41 | 0.13 | 1.32 | 0.13 |

OR, odds ratio; Lower CL, lower confidence limit; Upper CL, upper confidence limit.

Increment of 10 years or points.

Discussion

This study examined a comprehensive measure of decision quality, defined as the extent to which patients are informed, meaningfully involved and receive treatment that match their goals, in a sample of Latina breast cancer patients from Southern California. On average, the respondents were not well informed, were moderately involved in the decision‐making process and about three quarters received treatments that matched their goals.

In multivariable analyses, we examined the effect of acculturation level controlling for age, education and final surgical treatment. These variables have been shown to be associated with knowledge, one of the core components of decision quality.3 In univariate analyses, the level of acculturation was not correlated with age, but those with higher acculturation level had higher education and were more likely to have chosen lumpectomy. Our multivariable models were used to determine the effect of acculturation level if education and surgical treatment distribution were the same between the low‐ and high‐acculturation groups. As the adjusted effects of acculturation level were relatively small, it was not a significant predictor for any aspects of decision quality or decision regret based on this sample.

Although there are many studies documenting disparities in outcomes for Latina breast cancer patients, few studies have explored their experiences of decision making in depth. The reports from those studies have found that Latinas, particularly low accultured Latinas, tend to be less knowledgeable than Whites,7 less likely to be involved in decision making,4, 5 less satisfied with their decisions10 and have more regret.10 In contrast, our data did not support our hypothesis that acculturation scores are associated with decision quality – measured with knowledge scores, decision process scores and rates of concordant care – or with regret.

Our findings suggest that knowledge scores do not vary significantly by level of acculturation. Further, the average knowledge score on the Breast Cancer Surgery DQI in this sample was similar to that found in a predominantly White, well‐educated sample of breast cancer survivors (49 vs. 53%).3 On the other hand, Hawley et al. 7 reported that knowledge gaps for survival and recurrence were greater for minority respondents, including Latinas. About half of the patients in the Hawley study correctly responded that survival was the same with either lumpectomy or mastectomy, with 57% of Whites and 37% of Latinas answering correctly.7 In our study, 61% of Latinas answered a knowledge item on survival correctly (with similar proportions of low and high accultured Latinas answering correctly, 59 vs. 64%, respectively). Some key differences in the knowledge measures used might explain the conflicting results as the Hawley study used only two true/false/don't know knowledge items and found that more minority respondents in the Hawley study selected that incorrect response. Whether knowledge varies by acculturation or not, our study, and others, suggests that Latina patients have considerable knowledge gaps.

Involvement in the decision‐making process is an important component of shared decision making. Hawley et al.7 found that Latina, White and African‐American groups reported similar levels of patient‐based decision making, and although Latinas who preferred Spanish reported slightly lower levels than Latinas who preferred English, the results were not statistically significant. In this study, acculturation levels were also not significantly associated with the reported involvement in surgical decision making. Using the decision process items from the Decision Quality Instrument, Lee et al.3 found that 58% of a predominantly White, non‐Hispanic sample reported both surgical options were discussed (compared with 68% in this study), and only 49% reported being asked for their treatment preference (compared with 69% in this study). Surprisingly, the Latina respondents in this sample reported more interaction with health‐care providers than found in a study of White, well‐educated breast cancer survivors using the same survey items.

There is some evidence to support our second hypothesis that poor decision quality is associated with decision regret. A sizeable portion of respondents indicated some regret (39%) about their surgical decision. Two elements of decision quality were significantly associated with regret in univariate analyses, the amount of involvement in the decision‐making process and whether or not the patients received treatment that matched their goals. Only the decision process score remained significant in multivariable analyses, as those reporting more involvement in decision‐making process were less likely to report regret. Other studies have found that increased patient–physician communication around treatment decisions has been associated with higher satisfaction with breast cancer care.11, 12

This cross‐sectional study has several limitations. The study was retrospective, and respondents were up to 2 years out from their diagnosis, which may result in recall bias. In particular, knowledge scores may be higher if assessed closer to the decision. The survey was conducted in two counties in California, and therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to Latinas in other areas of the USA. The sample was small, and it is possible that we did not have the power to detect differences in acculturation. Another possible limitation is that the measure of acculturation (SASH) may not be sufficient. Research by Hunt et al. 13 argues that acculturation is extremely complex, it is too vaguely defined in the literature and that surveys do not cover all of the elements required for accurately assessing acculturation.

There was a low response rate that was partly a result of study staff turnover and lack of consistency in adhering to the protocol, particularly the timing of the reminders. It may also reflect a lack of acceptability of the survey to Latina respondents. We do not have information on non‐responders and cannot determine whether there was a systematic bias in response. Our initial protocol, which required potential respondents to request the survey in English, may have resulted in lower response for higher accultured participants. Further, the knowledge items had high levels of missing responses, raising questions about the feasibility of that portion of the survey. The items that had the most missing responses were in a table format, which may be more difficult for lower literacy samples to complete. Interestingly, the open‐ended, quantitative knowledge items had few missing responses (4% each). Future studies may explore including an ‘I am not sure’ response for the knowledge items to decrease missing responses; however, this will also likely reduce the knowledge scores as minority respondents appear to be more likely to choose this option.7 The other sections of the Decision Quality Instrument had very low missing items, providing support for their feasibility in this sample.

Conclusions

The Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument generally performed well, but may require some adaptations to the knowledge items to increase acceptability and feasibility in the Latina population. The study found considerable gaps in knowledge, but fairly good reports of involvement in decision making and concordance. Of note, respondents who reported more involvement in decision‐making process were less likely to report decision regret. The lack of significant differences in decision quality or decision regret between those with low‐ and high‐acculturation scores may suggest that there are not large disparities in these aspects of care.

UCI Acknowledgement and disclaimer

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting programme mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201000036C awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201000034C awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #1U58 DP000807‐01 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s), and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Funding

Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, Boston, MA, USA.

Conflict of interests

Drs. Sepucha, Chang and Ziogas receive research and salary support from the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, a not‐for‐profit (501 (c) 3) private foundation. The Foundation develops content for patient education programmes. The Foundation has an arrangement with a for‐profit company, Health Dialog, to co‐produce these programs. The programmes are used as part of the decision support and disease management services Health Dialog provides to consumers through health‐care organizations and employers.

Acknowledgements

A portion of this work was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Medical Decision Making in October 2012. This work was funded by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation.

References

- 1. Collins ED, Moore CP, Clay KF et al Can women with early‐stage breast cancer make an informed decision for mastectomy? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2009; 27: 519–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Chang Y et al Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer surgery. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 2012; 12: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee C, Chang Y, Adimorah N et al Decision making for surgery for early‐stage breast cancer. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 2012; 214: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Ratliff CT, Leake B. Racial/ethnic group differences in treatment decision‐making and treatment received among older breast carcinoma patients. Cancer, 2006; 106: 957–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS et al Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2009; 101: 1337–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Napoles‐Springer A, Livaudais J, Bloom J, Hwang S, Kaplan C. Information exchange and decision making in the treatment of Latina and white women with ductal carcinoma in situ . Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 2007; 25: 19–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hawley ST, Fagerlin A, Janz NK, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic disparities in knowledge about risks & benefits of breast cancer treatment: does it matter where you go? Health Services Research, 2008; 43: 1366–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin B, Otero‐Sabogal R, Perez‐Stable E. Development of a short acculturation scale for hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 1987; 9: 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST et al Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population‐based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2009; 18: 2022–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawley S, Janz NK, Hamilton A et al Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Education Counseling, 2008; 73: 363–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mandelblatt J, Figueiredo M, Cullen J. Outcomes and quality of life following breast cancer treatment in older women: when, why, how much, and what do women want? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2003; 17: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mandelblatt J, Kreling B, Figueiredo M, Feng S. What is the impact of shared decision making on treatment and outcomes for older women with breast cancer? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2006; 24: 4908–4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should, “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Social Science & Medicine, 2004; 59: 973–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]