Abstract

Background

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, degenerative condition with an estimated UK prevalence of 100 000. Contact with health‐care services is frequent and long‐term; however, little research has investigated the experiences of health care for MS in the UK.

Objective

The aim of this systematic narrative review was to critically review qualitative studies reporting patients' experiences of health‐care services in the UK.

Search strategy

EMBASE, CINAHL, Medline, psychINFO and MS Society databases were searched with no date restrictions using search terms denoting ‘Multiple Sclerosis’, ‘health‐care services’, ‘patient’, ‘experience’ and ‘qualitative research’. Snowballing and hand searching of journals were used.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included if they used qualitative methods of data collection and analysis to investigate adult patient's experiences of health‐care services for MS in the UK.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted independently and analysed jointly by two reviewers. Studies were appraised for the quality of evidence described using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme's qualitative tool. Due to the breadth of areas covered, the data were too heterogeneous for a synthesis and are presented as a narrative review.

Main results and discussion

Five studies were included. Studies primarily investigated diagnosis or palliative care. Themes of importance were the emotional experience of health care, continuity of care and access to services, and support from health‐care professionals. Studies were mainly poor quality and focussed on a homogenous sample.

Conclusions

This study provides the first review of the UK evidence base of experiences of health care for MS. Future research should investigate experiences of care after diagnosis in a more varied sample of participants.

Keywords: Multiple Sclerosis, narrative review, patient experience, qualitative, systematic review

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, degenerative neurological condition with an estimated prevalence of 100 000 people in the UK.1 A higher proportion of females are diagnosed with MS, with a gender ratio of 4 : 1.2 Patients present with a wide variety of symptoms, including visual impairment, mobility impairment or paralysis, incontinence, fatigue, pain, spasms, problems with coordination and cognitive dysfunction.3

There are several subtypes of MS including relapsing‐remitting and progressive forms; consequently, the health‐care needs of people with MS may differ according to their subtype and symptoms.4 Thus MS can be a complex and difficult condition to diagnose, to experience and to manage, and the uncertain prognosis may cause difficulties in managing the disease for both doctors and patients, including the creation and maintenance of long‐term treatment and rehabilitation plans.5

In the UK, management of people with MS should be by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) with the aim of treating relapses, preventing further relapses through disease‐modifying treatments, managing symptoms such as pain or incontinence and providing rehabilitation services.6 Patients may receive both primary care services and specialist Neurology services, often comprising a Consultant Neurologist and an MS Specialist Nurse, although provision varies by locality. Some teams may include allied health professionals such as Occupational Therapists or Physiotherapists. The severity and progressive nature of symptoms of MS may necessitate input from palliative care services.7

Although a number of systematic reviews exist on pharmacological treatments and physical rehabilitation for MS,8, 9 to date no systematic review exists of the literature reporting experiences of UK health care by people with MS. An increased importance has been placed on the patient experience by national health‐care policy10 which outlines plans for increasing patient choice and providing more sensitive, flexible health care, where patients have greater control and involvement in decision making.

Qualitatively investigating patients' experiences of health‐care services allows health‐care professionals, commissioners and policy makers to identify areas in need of intervention that may not be identified or explored fully through traditional surveying methods such as questionnaires.11 The aim of this systematic review was therefore to identify and present the available qualitative literature exploring the experiences of MS patients' use of health‐care services in the UK.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies eligible for inclusion were those that qualitatively investigated patients' experiences, views, attitudes to and perceptions of health‐care services for MS in the UK. No time limit was imposed on searches as this was an original review.

Qualitative research, for this purpose, was defined by the Cochrane qualitative methods group,12 as using both a qualitative data collection method and qualitative analysis. Both quantitative and mixed method studies were therefore excluded.

The definition of a patient for this study was adults (aged 18‐years old and over) with a diagnosis of MS, who had experience of utilizing health‐care services at any time point. We chose to specify adults as there are differences in paediatric and adult health care for MS in the UK which may have made comparisons difficult. Also, paediatric MS cases are estimated to make up <5% of the total population of people with MS.13 There were no restrictions on subtype of MS, gender, ethnicity or frequency of use of health care.

We defined experience using a definition from a narrative review investigating experiences of health care for another condition, (Sinfield et al. p. 301)14 as ‘Patients’ reports of how care was organised and delivered to meet their needs’. Patients' reports could refer to either experience of health‐care services delivery and organization overall, or their experiences of care by specific health‐care personnel.

Due to the focus on MS, studies were excluded if they used a mixed sample of various conditions (e.g. a mixed sample of people with neurological conditions or a mixed sample of people with MS and people with Huntington's disease) or if they used a sample of mixed respondents (i.e. people with MS and their carers) where results of patients with MS could not be clearly separated. If a paper focussed on MS and had a section or subtheme on health‐care services, however this was not the main research area of the paper, then that study was included; however, only data from the relevant subtheme were extracted and included in the findings. Finally, studies investigating quality of life were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria were non‐English language papers, papers that only described carer or health‐care professional experiences not patient experiences, editorials and commentaries.

Search strategy

A list of search terms was created in collaboration with a Specialist Librarian, an Information Scientist and the wider research team. Terms were grouped within the categories: (i) MS, (ii) health care services, (iii) patients/service‐users, (iv) experience/opinions/perspectives, and (v) qualitative research.

The search strategy comprised groups of free text and MESH headings divided into the categories of terms described above, which were then searched together using the AND function. A separate search strategy was used for each database to ensure that the terms and MESH headings used were relevant for each particular database. The full search strategy is presented in Table S1.

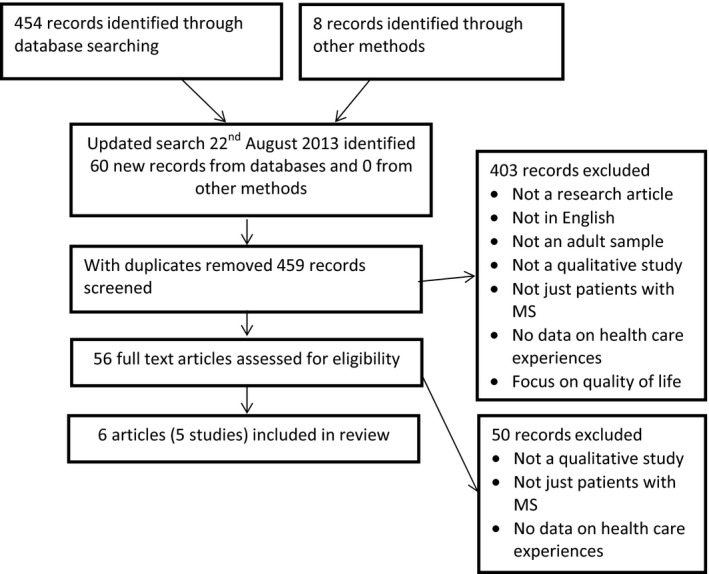

Databases searched included psycINFO, Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL and the MS Society library. Reference lists of included papers were searched for additional relevant references. The Multiple Sclerosis Journal was hand searched from inception in 1995 until August 2012. A further search was also conducted in the British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing using the words ‘Multiple Sclerosis’ and ‘Qualitative’. Grey literature outside that contained within the MS society library was not searched due to resource constraints. The search was not limited by geographical area to ensure that studies were not missed due to incorrect labelling. However, only studies that reported on UK services were included. An updated search was run on 22nd August 2013 (Figure 1), however no new papers were identified.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram detailing the process of searching and identifying relevant papers.

Data management and quality appraisal

One reviewer (AM) judged titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. If a title and abstract met the inclusion criteria then full text copies of all articles were retrieved for further investigation. Two reviewers (AM and SCS) then independently assessed these articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion. Data from included studies were extracted by both reviewers independently to ensure accuracy and then stored on a Microsoft Excel spread sheet.

Extracted data were then appraised for quality using an expanded version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) criteria15 modified for thematic syntheses with qualitative literature.16 Quality was independently appraised by two authors who met to decide a consensus. As some questions in this modified CASP tool could be subjective and difficult to grade (e.g. ‘what is your overall view of this study?’ graded from 1 = Excellent to 6 = Very poor) we followed the process detailed in Masood et al.,17 where the percentage of CASP criteria met by each paper was taken as an indicator of quality (Table 1). We therefore removed all questions that required grading and marked remaining questions in terms of whether evidence was present (1 = Yes) or absent (2 = No) (see Table S2 for more information).Studies were not excluded on grounds of quality, instead this information was used to present the quality of evidence available on this topic, for discussion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 5)

| Source article | Setting (hospital/community) | Sample | Research design | Aims | Word count | Overall quality assessment (% of CASP criteria met) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edwards et al.20 | England, Birmingham. (Recruited through MS Society and local newspaper) | N = 24. Age range 35–72 years. 17 f and 7 m. Disease duration 1–37 years. 23 Caucasian | Semi‐structured telephone interviews with thematic content analysis | To examine patients' experiences of being diagnosed with MS, information given at the time, treatment and the impact on their lives | 3183 words | 59.5% |

| Embrey19, 20 | England, Staffordshire. (Recruited through hospice day care) | N = 9 | Interviewed using an open‐ended question approach and analysed using Giorgi's (1985) framework analysis | To explore the experiences and views of people with moderate and severe MS participating in a palliative day care programme offered at a hospice in North Staffordshire | Paper 1: 3664 words Paper 2: 4180 words | 40.5% |

| Johnson21 | England, Southeast. (Recruited through hospital database) | N = 24. Interviewed in 2 cohorts. Cohort 1: Age range 37–67. Cohort 2: Age range 34–66 years. Cohort 1: 6 m, 6 f Cohort 2: 4 m, 8 f. Cohort 1: Age of onset 24–59. Illness duration 0.4–26 years. Cohort 2: Age of onset 21–51 years. Illness duration 0.4–33 years | Interviewed one cohort before and one after the implementation of an MS Specialist Nurse. Analysed with thematic analysis | To investigate patient's experiences of receiving a diagnosis of MS | 3923 words | 48.6% |

| Laidlaw & Henwood (2003)22 | England, London. (Recruited through MS Society) | N = 8. 2 m, 6 f. | Unstructured interviews and open thematic analysis | To investigate MS Patients' holistic experience of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | 3604 words | 51.4% |

| Malcomson, Lowe‐Strong & Dunwoody23 | Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland (Recruited through MS Society) | N = 13. Aged 40–67 years. 1 part time, 3 unemployed, 5 homemakers, 4 retired. Group 1: 5 f, 1 m. Group 2: 4 f, 3 m. 6–30 years since diagnosis. 6 relapsing‐remitting, 6 secondary progressive, 1 primary progressive. Ambulant with aids (n = 8), Wheelchair (n = 2), Independently mobile (n = 3) | Two focus groups and thematic analysis | To explore personal accounts and experiences of individuals with MS who felt able to cope with the disease in day‐to‐day life | 7997 words | 59.5% |

Results

The majority of papers were excluded because they did not report qualitative methods, yet contained words that were relevant search terms such as ‘patient’, ‘knowledge’, ‘experience’ which were frequent key words for questionnaire studies on patient experience and satisfaction. Papers that were excluded at the full text stage contained samples of both people with MS and another group, for example, carers that was not explicit in the title and abstract.

The search identified five studies (presented in Figure 1) that fitted the inclusion criteria (two publications reported different results from the same study18, 19) as. Information about these studies is presented in Table 1. Although no date restrictions were set, all studies found were published between 2003 and 2008. The majority of the studies were conducted in England (n = 4),18, 19, 20, 21, 22 with one in Northern Ireland.23 Levels of demographic reporting varied widely. Discussion of ethnicity was virtually absent with only one study reporting this information.20 Embrey18, 19 only provided information on the number of participants. Similarly, Laidlaw and Henwood22 only provided the sample size and gender of participants. In the other three studies20, 21, 23 participants were aged from 34 to 72 years, with a disease duration of between 0.4–37 years. Only one study23 provided an in‐depth profile of disease progression, reporting that the majority of their sample were ambulant with aids, an equal number of participants with relapsing‐remitting and secondary progressive MS were included and the majority of participants were homemakers or retired. Four studies18, 19, 20, 21, 22 collected data using interviews (unstructured22 or semi‐structured interviews18, 19, 20, 21) and one study utilized focus groups.23 Thematic analysis was the predominant analytic method utilized,20, 21, 22, 23 although a named method of analysis, Giorgi's (1985) framework analysis was reportedly used in one study.18, 19

Quality appraisals

The overall quality scores attributed to the publications are presented as the percentage of CASP criteria met (see Table 1 and Table S2). The highest scoring studies only scored 59.5% of criteria met, whilst the lowest rated study scored 40.5%. Studies frequently failed to report their justifications of both sample size and the reasons for selecting a particular sample. Whilst studies were usually very clear on how data were collected and recorded, poor reporting of analysis was a major contributor to low scores. For example, four studies20, 21, 22, 23 reported using a form of thematic analysis but made no reference to an iterative process. Only one study18, 19 reported a theoretical perspective (Phenomenology). Findings were, overall, clearly reported; however, a lack of demographic information made it difficult to assess the transferability of findings.

Data analysis

Once the data had been extracted, it became clear that the relative paucity of papers identified for inclusion, and the breadth of areas researched in these papers, ensured that resulting data were too heterogeneous to utilize an in‐depth qualitative synthesis method such as a meta‐ethnography (as proposed by Sandolowski et al.24). Therefore, as outlined in previous studies investigating qualitative research, for example, Lie et al.25 it was necessary to utilize a narrative summary approach to present the main findings of all studies in a narrative form. Both authors summarized the findings of the studies and compared them to check for accuracy and consistency. Once this was completed, the aims and topics explored in these studies were compared. The reported aims of these studies could be broadly categorized into two areas, the process and experience of diagnosis (n = 4)20, 21, 22, 23 and palliative care (n = 1).18, 19 These findings will now be presented in the form of a narrative summary.

Diagnosis

Studies focussed on the experience of various aspects of diagnosis. Subthemes of information and experiences of access to services and health‐care support were found to mediate emotional reactions and improve the emotional experience of diagnosis. Information was key for the diagnostic process whilst access to services and health‐care professional support were highlighted as subthemes for continued care.

Three studies reported a prolonged investigative process, negative experiences of receiving a diagnosis20, 21, 23, and two studies reported dissatisfaction with the way in which diagnosis was managed.21, 23 Time taken to reach a definite diagnosis was sometimes lengthy20, 21, 22, 23, 24, in two studies patients reported waiting over 17 years for a diagnosis;20, 23 however, one study reported a participant's confirmation of a diagnosis of MS in <2 years23 and another study reported cases diagnosed within 12 months.20 In summary, the process of diagnosis was overall a negative and lengthy experience.

Emotional reactions to the diagnostic process were widely reported and transcended all stages of diagnosis.20, 21, 22, 23 Before diagnosis, reported emotions were an awareness that something was wrong, distress, uncertainty, fear and anxiety.21, 23 During the diagnostic testing period these emotions continued to be present. After diagnosis, emotional responses were described as devastating or shocking unless MS patients had prior suspicions of MS,21, 23 although feelings of relief at the identification of the condition were also reported.21, 23

Information received

Information was described as necessary for participants to understand their MS and a lack of timely information was found to cause increased anxiety and distress.22 A lack of advice and information about MS at the time of diagnosis and difficulties accessing information regarding MS was reported.20 MS knowledge at the time of diagnosis was reportedly important for all participants in one study and this involved a process whereby the participants became more informed and were able to identify relevant support services.21 Another study highlighted that provision of information on the MS society at the time of diagnosis would have been beneficial.22 The only study reporting the experiences of MRI scanning, revealed a lack of information at all stages of the MRI scan: before scanning, at the time of the scan and when the results were ready.22 One study reported conflicting findings: a small number of participants were happy with the information provided, however many more reported that they had not had adequate information or advice on MS.20 Dissatisfaction with health‐care services was commonly linked to lack of information provision and understanding.22, 23

This reported lack of information caused anxiety and fear and lessening patient perceptions of control of both the scanning experience and MS in general.22 Frustrating encounters were reported with health‐care professionals, including General Practitioners (GPs), who could not provide information on MS and relevant support services, in comparison to occupational therapists, physiotherapists and community nurses who were felt to be more knowledgeable.21 In one study, participants reported that their GPs were ill‐informed and not knowledgeable on MS.20

Timeliness and access to information is therefore of great importance, and variation was found in the level of knowledge of MS demonstrated by health‐care professionals.

The post‐diagnostic phase: access to services and experiences of health‐care professional support

Difficulties were also reported in accessing treatments for their MS later on in the disease course20 and a focus on physical health needs at the exclusion of psychosocial support.23 One study reported mixed findings, as whilst a small number of participants were happy with the care they received. Overall, most of the participants in this study received little or no treatment for MS and were often refused funding for treatment by the National Health Service (NHS).20

Continuity of care was an issue at the time of diagnosis, and later on bridging diagnosis and subsequent care. Neurologists were reported as trying to solve the puzzle of MS and then withdrawing when that was achieved.21 In one study, participants reported feeling abandoned and isolated by the health‐care system, unless they received support from another health‐care professional, such as a GP or MS Nurse.21

Two studies discussed unsatisfactory health‐care professional support.20, 23 Communication with health‐care professionals was perceived negatively by participants in one study who reported that their professionals had been off‐hand, casual and unsympathetic.20 Participants in another study recalled their diagnosis being given in a manner that lacked sensitivity, empathy and understanding.23

Participants in one study reported difficulties in initiating symptom investigation as they felt they were not believed by health‐care professionals.20 This study also reported that although a suspicion of MS was noted in their medical records they were not informed of this.20 Access to health care and the professional manner and communication demonstrated by health‐care professionals has a large impact on participants' experiences of continuing health‐care services for MS.20, 21, 22, 23 Continuity of care, and specifically poor experiences of continuity, between different health‐care providers and services is therefore a key factor in the experiences of MS patients.

Palliative care

Embrey,18, 19 was the only study (reported across two publications) to report on the experience of palliative care for MS patients. Therapeutic interventions were found to improve symptom relief, provide a sense of achievement and fun, improved optimism and provide an opportunity for health promotion, although a downside was the infrequency of therapeutic interventions and worries over continuity of this palliative care service. Group support provided friendships based on common conditions and problems, allowed an awareness of each others' problems, provided positive experiences with hospice staff and reduced carer burden by providing time off for carers. Participants reported being initially fearful and worried about using a hospice but appreciated the relaxed environment which improved their self‐confidence.

Further analysis

Once this was completed, it was felt it would be of value to see whether there were any tentative commonalities between these two areas of care. Whilst a full meta‐ethnography was not possible, the initial elements of a basic thematic synthesis were conducted. As outlined in Thomas and Harden,26 line‐by‐line coding was completed for all sentences in the findings sections of the six included studies. Next, two authors (AM and SCS) jointly compared these codes to create overarching themes.

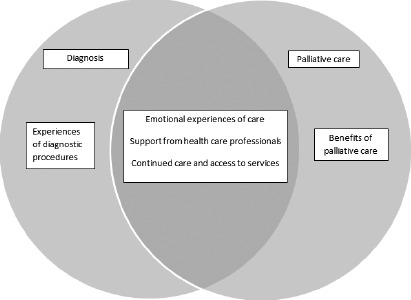

Despite the very different aims of diagnostic care services and palliative care, some themes of experiences emerged which transcended the care pathway (Figure 2), namely, the emotional experience of care, perceived support from health‐care professionals and the importance of continued care and access to services. Two themes were developed which were unique to the particular care setting: experiences of diagnostic procedures and the benefits of palliative care services. These five themes were then discussed within the larger research team (all four authors) to check consistency of interpretation and ensure that the themes were grounded in the studies and not extrapolated beyond the data. Due to the limited and varied nature of the data, we did not complete the defining stage of a narrative synthesis, which was to ‘go beyond’ the content of the original studies to create an explanation of experiences of health care or generate theory on this topic.27

Figure 2.

Presentation of themes from diagnosis and palliative care studies.

Discussion

Included studies fell broadly into two distinct areas of research: experience of diagnosis and experience of palliative care. However, similarities were identified between the two areas of care in terms of issues with health‐care professional support, access to continued care and the emotional experience of using health‐care services.

Primarily, descriptions of diagnosis presented mainly negative experiences and poor service provision, suggesting this is still an area in which MS care can be improved, as reported in the included papers by people with MS from across the UK.

Implications for practice and research

Communication with health‐care staff has been a key finding in research investigating MS care.28, 29 However, as the studies in this review were relatively recent, they suggest that this is still a current and significant issue, despite being noted as a key principle of the 2003 NICE guideline for MS recommendations for clinical practice.6 A clinical priority should therefore be to improve health‐care professionals' awareness of the emotional impact of ineffective communication, with the provision of medical education and training on appropriate styles of communication if necessary, similarly to those utilized in oncology services.30

This review highlighted the emotional reactions people with MS experience in relation to their symptoms, and the treatment they receive, particularly during diagnosis when uncertainty, fear and anxiety appear at their highest. The NHS has previously acknowledged the need to improve the patient emotional experience in order to improve patient experiences overall31 and this is evidently necessary for patients with MS.

A lack of timely information on diagnosis, living with MS and treatment was found to directly link to negative emotional states such as anxiety and fear. Providing timely and credible information on these topics should therefore be a priority in improving the patient emotional experience.31

The included studies suggested that the experience of diagnosis could be improved by better responsiveness and increasing the continuity of care between and within primary, community and specialist care and ensuring that relevant emotional and informational support structures are in place for people receiving a diagnosis of MS. Although all studies in this review were published within the last decade, many participants in these studies had been diagnosed for a long period of time before these studies took place. It is possible that a perceived improvement of MS patient experiences occurred due to earlier or more timely diagnosis as a result of the increasing use of technology such as MRI to identify lesions suggestive of MS.32 It may also possibly be due to the increased support and information provided by MS Specialist Nurses since the increasing implementation of their role throughout the 2000s;33 however, these assertions cannot be confirmed from the evidence provided by the included studies.

Implications for commissioning

Patient concerns over the continuity and quality of care services in the UK are a pertinent and current issue due to budget restrictions and the cessation of certain National Health Service (NHS) facilities.34 Access difficulties due to funding restrictions, or procedures, may change with changes accompanying the Health and Social Care Act 2012.35 The inclusion of neurological conditions (including MS) in one of the four strategic clinical networks is hoped to improve the continuity of care across primary and secondary care services, and provide expert clinical information to the commissioners of services for this patient group.36 This strategic clinical network also encompasses mental health care, reflecting that the UK now has an increasing focus on prioritizing mental health needs in people with physical health conditions,37 including MS. However, a service audit of MS care in 2011 revealed difficulties accessing relevant services dependent on local funding priorities, referrals and availability of services,38 and further variety may be displayed due to the priorities of clinical commissioning groups.10 It will therefore be necessary for further research to investigate these issues within the new NHS structure.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Due to time and resource restrictions, only the four major databases for this research topic were searched and only English language papers were included, potentially limiting the number of relevant papers identified.

The conclusions presented are drawn from a limited body of research, some of poor quality methodology or reporting. There is therefore a need to utilize high quality qualitative research to gain a more thorough understanding of the full health‐care experience for people with MS, to maintain or improve the health‐care experiences provided.

To date, there are few qualitative studies published on the health‐care experiences of people with MS and those that exist have been limited to issues around diagnosis and palliative care. Although palliative care was found to provide a positive experience with increased peer support and psychological and physical benefits, little qualitative evidence exists on this aspect of care. Overall, the available body of literature omits many aspects of MS care, as the studies identified only cover the very beginning and the very end of the health‐care pathway, with no investigations of rehabilitation and continuing care experiences.

From the limited demographic data provided, it is difficult to assess how well the above findings represent the experiences of a wide variety of people with MS. From the available information, it appears that more participants under the age of 35 should be studied, as MS can be diagnosed from childhood1; however, the views of young adults with MS are currently unrepresented in the literature. In addition, only one study reported ethnicity data, leaving a large gap in our knowledge of any differences of experiences between ethnic groups. As MS may affect people from all ethnic groups1 and there are well‐established difficulties in help seeking and barriers to accessing health care reported by people from ethnic minority backgrounds,39 it would appear pertinent to explore the views of these individuals.

Summary

This review provides an overview of the literature relating to MS patient experiences of health care in the UK and two discrete areas of research into diagnosis and palliative care. Diagnosis was presented as a primarily negative experience whilst the limited evidence on palliative care suggested a positive experience. Themes of importance for both areas were found to be the emotional experience of health care, continuity of care and access to services, and support from health‐care professionals. These themes present areas of high importance for the designing, commissioning and delivery of clinical care which require attention and change. However, the empirical evidence is currently limited to a homogenous group of patients' experiences of the start and end of the illness trajectory. This therefore leaves a considerable gap in knowledge relating to the majority of the illness management experience and the views of minority groups including young people and those from ethnic minorities. Future research should work to improve patient care in these areas and provide knowledge on the experiences of care across the care pathway.

Sources of funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and or publication of this article: National Institute of Health Research, School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR) studentship.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supporting information

Table S1. Search terms for all databases.

Table S2. Quality appraisal of included studies.

Acknowledgements

This project was fully funded by a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR) PhD studentship. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors would like to thank Dr Gavin Daker‐White, Dr Charlotte Garrett, Dr Caroline Sanders and Katie Paddock for their feedback and support. The authors would like to thank Professor Peter Bower for providing advice on the design of the study. The authors would also like to thank Rosalind McNally for appraising the search strategy and providing suggestions for improvements.

References

- 1. Alonso A, Jick S, Olek M, Hernín M. Incidence of multiple sclerosis in the United Kingdom. Journal of Neurology, 2007; 254: 1736–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cutter G, Yadavalli R, Marrie R‐A et al Changes in the sex ratio over time in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology, 2007; 68 (Suppl.): 162. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Compston A, McDonald IR, Noseworthy J et al McAlpine's Multiple Sclerosis. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holland NJ, Schneider DM, Rapp R, Kalb RC. Meeting the needs of people with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, their families, and the health‐care community. International Journal of MS Care, 2011; 13: 65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter H, McKenna C, MacLeod R, Green R. Health professionals' responses to multiple sclerosis and motor neurone disease. Palliative Medicine, 1998; 12: 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) . Multiple Sclerosis: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Management in Primary and Secondary Care, NICE clinical guideline 8. National Institute for Clinical Excellence: London, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Higginson IJ, Hart S, Burman R, Silber E, Saleem T, Edmonds P. Randomised controlled trial of a new palliative care service: compliance, recruitment and completeness of follow up. BMC Palliative Care, 2008; 7:7. doi: 10.1186/1472‐684X‐7‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosti‐Otajärv EM, Hämäläinen PI. Neuropsychological rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2011; Issue 11. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009131.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rice GPA, Incorvaia B, Munari LM et al Interferon in relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2009; Issue 4. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Department of Health . Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. London: The Stationary Office Limited, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pope C, Van Royen P, Baker R. Qualitative methods in research on health care quality. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 2002; 11: 148–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Noyes J, Popay J, Pearson A, Hannes K, Booth A. Chapter 20: Qualitative research and Cochrane reviews In: Higgins JPT, Green S. (eds) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed 7th May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duquette P, Murray TJ, Pleines J et al Multiple sclerosis in childhood: clinical profile in 125 patients. Journal of Pediatrics, 1987; 111: 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sinfield P, Baker R, Camosso‐Stefinovic J et al Mens' and carers' experiences of care for prostate cancer: a narrative literature review. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Solutions for Public Health . Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Appraisal tool. Available at: http://www.casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/CASP_Qualitative_Appraisal_Checklist_14oct10.pdf, accessed 24 March 2013.

- 16. Campbell R, Pound P, Daker‐White G et al Evaluating meta‐ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technology Assessment, 2011; 15: 1–164: doi: 10.3310/hta15430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Masood M, Thaliath ET, Bower EJ, Newton JT. An appraisal of the quality of published qualitative dental research. Community Dent Oral Epidemiology, 2011; 39: 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Embrey N. Exploring the lived experience of palliative care for people with MS, 2: Therapeutic interventions. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 2009; 5: 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Embrey N. Exploring the lived experience of palliative care for people with MS, 3: Group support. British Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 2009; 5: 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edwards RG, Barlow JH, Turner AP. Experiences of diagnosis and treatment among people with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2008; 14: 460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson J. On receiving the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: managing the transition. Multiple Sclerosis, 2003; 9: 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laidlaw A, Henwood S. Patients with multiple sclerosis: their experiences and perceptions of the MRI investigation. Journal of Diagnostic Radiography and Imaging, 2003; 5: 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malcomson KS, Lowe‐Strong AS, Dunwoody L. What can we learn from the personal insights of individuals living and coping with Multiple Sclerosis? Disability and Rehabilitation, 2008; 30: 662–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Research in Nursing & Health, 1997; 20: 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lie MLS, Robson SC, May C. Experiences of abortion: a narrative review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Services Research, 2008; 8: 150. doi: 10.1186/1472‐6963‐8‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta‐ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 2002; 7: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thorne S, Con A, McGuinness L, McPherson G, Harris SR. Health care communication issues in Multiple Sclerosis: an interpretative description. Qualitative Health Research, 2004; 14: 5–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edmonds P, Vivat B, Burman R, Silber E, Higginson IJ. ‘Fighting for everything’: service experiences of people severely affected by multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 2007; 13: 660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schofield NG, Green C, Creed F. Communication skills of health‐care professionals working in oncology – can they be improved? European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 2008; 12: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Department of Health . Now I Feel Tall: What a Patient Led NHS Feels Like. London: Department of Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Granberg T, Martola J, Kristoffersen‐Wilberg M, Aspelin P, Fredrikson S. Radiologically isolated syndrome – incidental magnetic resonance imaging findings suggestive of multiple sclerosis, a systematic review. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 2013; 19: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DeBroe S, Christopher F, Waugh N. The role of specialist nurses in multiple sclerosis: a rapid and systematic review. Health Technology Assessment, 2001; 5: 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. The King's Fund . How is the NHS Performing? Quarterly Monitoring Report. London: The King's Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. House of Commons . The Health and Social Care Act 2012. London: The Stationary Office, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36. NHS Commissioning Board . The way forward: Strategic Clinical Networks. NHS Commissioning Board Authority website. (July 2012). Available at: http://www.commissioningboard.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/way-forward-scn.pdf

- 37. Department of Health . No Health Without Mental Health: A Cross‐Government Mental Health Outcomes Strategy for People of Ages. London: Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Royal College of Physicians . The National Audit of Services for People with Multiple Sclerosis. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Szczepura A. Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 2005; 81: 141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Search terms for all databases.

Table S2. Quality appraisal of included studies.