Abstract

Background

The patient‐as‐professional concept acknowledges the expert participation of patients in interprofessional teams, including their contributions to managing and coordinating their care. However, little is known about experiences and perspectives of these teams.

Objective

To investigate (i) patients’ and carers’ experiences of actively engaging in interprofessional care by enacting the patient‐as‐professional role and (ii) clinicians’ perspectives of this involvement.

Design, setting and participants

A two‐phased qualitative study. In Phase 1, people with chronic disease (n = 50) and their carers (n = 5) participated in interviews and focus groups. Phase 2 involved interviews with clinicians (n = 14). Data were analysed thematically.

Findings

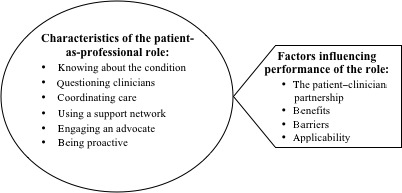

Patients and carers described the characteristics of the role (knowing about the condition, questioning clinicians, coordinating care, using a support network, engaging an advocate and being proactive), as well as factors that influence its performance (the patient–clinician partnership, benefits, barriers and applicability). However, both patients and carers, and clinicians cautioned that not all patients might desire this level of involvement. Clinicians were also concerned that not all patients have the required knowledge for this role, and those who do are time‐consuming. When describing the inclusion of the patient‐as‐professional, clinicians highlighted the patient and clinician's roles, the importance of the clinician–patient relationship and ramifications of the role.

Conclusion

Support exists for the patient‐as‐professional role. The characteristics and influencing factors identified in this study could guide patient engagement with the interprofessional team and support clinicians to provide patient‐centred care. Recognition of the role has the potential to improve health‐care delivery by promoting patient‐centred care.

Keywords: client, engagement, expert patient, health care, health professional, informed patient, patient, qualitative, self‐management

Introduction

Self‐management is an integral aspect of chronic disease management.1, 2 Its success, by definition, is dependent on the active engagement and empowerment of patients in the planning and provision of their care.3 The importance of empowerment is based on the idea that if patients feel confident in managing their condition they will be successful in doing so.4 In addition, patients who understand their condition and work in partnership with clinicians are more likely to follow their treatment plans.5 Patient engagement and empowerment can be supported by the involvement of carers in interactions with the health‐care system.

People with chronic disease often have multiple clinicians involved in their care across multiple care settings. Consequently, patients and their carers may receive conflicting advice, or clinicians may not have access to current care plans, reports and test results at appointments.6 This situation can leave patients vulnerable to diminished safety and quality of care if, or when, there is poor communication between providers. The impact of these circumstances may be overcome or minimized by supporting people with chronic disease and their carers to more actively engage in managing their care.6 Patient engagement has been driven by the moral imperative that patients should participate in decisions about their own health and those who do experience increased satisfaction and health.7 To achieve these potential benefits, it is increasingly expected that patients actively participate by contributing knowledge, skills and motivation.8

Health‐care consumers, encompassing both patients and carers, are known to fit into distinct groups based on how they engage in their health care.9, 10 These groups vary from consumers who actively seek information and make decisions, to passive recipients who regard themselves as being dependent on their clinicians.9, 10 Understanding the profile of each group can assist in engaging individuals in a way that will be most meaningful to them.9

Informed and expert patients illustrate the active engagement of people in their care. The emergence of the informed patient has been supported by increasing access to information on the internet.11, 12, 13, 14 However, patients report that clinicians often dismiss the information they present.11 This is possibly because informed patients can challenge clinicians’ knowledge and they need to spend additional time discussing information that the patient brings with them.12

Moving one step further, the expert patient is one who makes the day‐to‐day decisions about their health and works in partnership with their clinicians.15 The partnership is valuable to the planning and delivery of care because both parties bring complementary expertise. Patients bring expertise related to their experience of illness, social circumstances, attitude to risk, values and preferences.16, 17, 18 Clinicians contribute knowledge relevant to the diagnosis, disease aetiology, prognosis, treatment options and outcome probabilities.16 By combining this knowledge, clinicians and patients tailor management options to meet the needs and preferences of the patient and therefore achieve a successful outcome.18

The informed and expert patients demonstrate the increasing involvement of patients in their care. We propose the ‘patient‐as‐professional’ role, which progresses these roles to describe patients and carers who are collaboratively involved in their interprofessional care teams, contributing to the management and coordination of their care. Interprofessional care teams have overlap of professional roles, communicate formally and informally, and participate in shared problem‐solving to develop integrated and cohesive responses to the needs of the patient.19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The willingness of patients and carers to participate in their interprofessional team is a key aspect of this team.21 The patient‐as‐professional role acknowledges the time and effort which patients spend managing their health and their valuable contribution to the interprofessional team.24 It provides an avenue for validating the knowledge that patients, and their carers, bring about their everyday experiences of living with their conditions.25

Scant literature exists as to how patients, carers and clinicians perceive the involvement of patients in interprofessional teams. Existing evidence describes the barriers to patient and clinician involvement in interprofessional teams as including, intrapersonal, interpersonal and cultural factors.23, 26, 27 Further information is required to understand patient, carer and clinician perspectives of the usefulness of patient engagement in interprofessional teams; strategies for enabling such engagement; and experiences of enacting collaborative interprofessional care teams. This knowledge will identify the characteristics of enacting the patient‐as‐professional role and identify where supports and services can be enhanced to promote this role in interprofessional teams. Therefore, the aim of this study was to understand patients’, carers’ and clinicians’ perspectives and experiences of, and strategies for actively engaging in, interprofessional care by enacting the patient‐as‐professional role.

Method

Evidence to address the research aims were drawn from two phases of a larger cross‐sectional study investigating perspectives on chronic disease self‐management.28 In Phase 1, people with chronic disease and carers participated in focus groups29 or semi‐structured interviews30 and in Phase 2 clinicians were interviewed. The two phases occurred between August 2010 and January 2011. Ethics approval was gained from the Human Research Ethics Committees at the University of New South Wales (2009‐7‐13), the Australian National University (2010/349) and ACT Health (ETHLR.10.274). Informed written consent was obtained from participants.

Participants

In Phase 1, purposive sampling was used to recruit participants who identified themselves as having or caring for someone with a chronic disease. Multiple methods were used to recruit participants: (i) recruitment letters were mailed to people enrolled in a community‐based self‐management education course (the Stanford Program)31 through ACT Health (the local health service) over the previous 18 months; (ii) emails were sent to people with a chronic disease who participated in the development of a specific community‐based chronic disease self‐management training package; and (iii) the distribution of flyers and personal invitations at community organizations and activities, for example, a gymnasium and a pre‐existing physiotherapy group. These community groups were sourced via contacts from a previous project.32

In Phase 2, purposive sampling was used to recruit a range of clinicians [including nurses, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, fitness instructors, social workers and general practitioners (GPs) – also known as family doctors] who self‐reported experience in supporting patients to self‐manage.30 Twenty‐four eligible clinicians were approached by the chronic disease self‐management Clinical Nurse Consultant and through professional contacts of the research team. A flyer describing the project was also distributed with the monthly newsletter of the local academic unit of general practice. Clinicians interested in participating contacted the research team for further information.

Materials

Semi‐structured interview guides were developed based on knowledge gained from the literature and discussion with clinicians who ran self‐management services.30 The guides covered perspectives on chronic disease self‐management, self‐management support (findings reported in Phillips et al.33 and Hogden et al.), the patient‐as‐professional role and health literacy. This article reports on the themes and analysis relevant to patient engagement and the patient‐as‐professional role. The questions included to collect this data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interview guides

| Patient and carer interviews | Clinician interviews |

|---|---|

| 1. To what extent do you think that patients have knowledge that is useful to share in decision making with clinicians? If so, what types of knowledge and how? | 1. To what extent do you think that patients have knowledge that is useful to share in decision‐making with clinicians? If so, what types of knowledge and how? |

| 2. There is a concept called the patient‐as‐professional that is similar to the idea of being an expert or informed patient. The patient‐as‐professional sees the patient as a member of the health‐care professional team and is involved in shared decision making. What are your thoughts on this idea? Good and bad things? | 2. There is a concept called the patient‐as‐professional that is similar to the idea of being an expert or informed patient. The patient‐as‐professional sees the patient as a member of the healthcare professional team and is involved in shared decision making. What are your thoughts on this idea? |

| 3. How much do you like to be involved in your care? |

3. In your experience how do patients contribute knowledge to the decision‐making process? (a) What are the good aspects of this? (b) What are the bad aspects of this? |

| 4. If you took on the patient‐as‐professional role, do you think the care you receive would change? | 4. If a patient is taking on the patient‐as‐professional role, how would this change the care they receive? |

Data collection

In Phase 1, people with chronic disease and carers participated in either a focus group29, face‐to‐face or phone interview30 depending on location, availability and health needs. The research team endeavoured to involve all interested people in the study and sought opportunities to enable this. For example, one participant with a hearing impairment requested to complete the interview via email. In Phase 2, face‐to‐face interviews were arranged at a time and place convenient to participants.

Written notes and audio recordings were taken at interviews and focus groups with patients and carers. Only written notes were taken in interviews with clinicians. This was intended to maximize the engagement of clinicians who may be concerned about having a recording made of their perspectives about the care they provide.33 In their notes, the interviewers indicated when exact words were captured and could be used as quotes.19

Members of the research team, with backgrounds in allied health and public health, undertook the focus groups and interviews. The diversity of backgrounds enabled alternative perspectives to be discussed and considered during data collection and analysis. We ensured consistency and quality between team members by conducting initial training, using consistent materials and processes (for example, a data collection workbook and guidelines for transcribing) and regular meetings to identify and resolve issues.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to identify patterns emerging from the data across the different interviews and focus groups.34 The researchers first became familiar with the data by reading the transcripts.34 Emergent coding was then used by two researchers (RP and AK, who also collected data) who independently developed coding categories using an iterative process and identified preliminary themes.35 Subsequently, the researchers met to compare, discuss and integrate the themes. An additional researcher (AS) attended this meeting and assisted in the discussion and resolution of discrepancies generated.36 The data collected from patients and carers were combined for analysis because the same themes were emerging from both groups in initial analysis.

Findings

Perspectives and experiences of, and strategies for actively engaging in, interprofessional care by enacting the patient‐as‐professional role are first described for patients and carers, and then clinicians.

Phase 1: Patient and carer perspectives

A total of 55 participants were recruited to Phase 1 comprising people with a chronic disease (n = 50) and carers (n = 5). Three of the carers identified that they also had a chronic disease. Participants typically reported having, or caring for someone with, more than one chronic disease. See Table 2 for detailed participant characteristics. Data were collected via seven focus groups (ranging in size from two to 11 people, median = 6) and 11 interviews, varying in length between 70–90 and 20–120 min (mean = 85 min), respectively.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | Participants |

|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, range) | 63 (36–89) |

| Gender (n) | |

| Male | 17 |

| Female | 38 |

| Chronic disease (n) | |

| Heart condition | 11 |

| Lung condition | 8 |

| Musculoskeletal condition | 20 |

| Neurological condition | 12 |

| Renal condition | 2 |

| Mental health condition | 4 |

| Sensory condition (e.g. hearing or vision problems) | 2 |

| Autoimmune disorder | 1 |

| Chronic pain | 1 |

| Chronic fatigue | 3 |

| Obesity | 2 |

| Cancer | 2 |

| Diabetes | 11 |

| Not specified | 7 |

| Number of years chronic disease present (mean, range) | 18 (1–57) |

Most participants stated that being part of the interprofessional team, in the patient‐as‐professional role, is something that they try to do as part of self‐managing their conditions. They described the strategies used to enact the patient‐as‐professional role, as well as factors that influence this involvement (see Fig. 1). Each of the characteristics and factors are described in the following sections.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the patient‐as‐professional role and influencing factors.

Characteristics of the patient‐as‐professional role

Participants explained that part of participating in the interprofessional team was knowing about their conditions so that they could contribute valuable information. This included learning about their condition, its symptoms and management, as well as educating family and friends about the condition. Generally, people with chronic disease also reported monitoring their own symptoms so that they could present an accurate summary at their next health‐care appointment. They also emphasized their role involved relentlessly following up the cause of symptoms that had not yet been adequately addressed.

I told the doctors I knew my body and that when the tests showed nothing that they should have looked elsewhere. I had to keep nagging to get follow‐up. If I hadn't kept at them, nothing would ever have happened (Interview 2, female patient with complicated migraines)

Proactive engagement with clinicians was identified as a strategy for participating in the interprofessional team. Patients elaborated that proactive engagement involved informing clinicians about their current health, agreeing or disagreeing with their clinician's advice and asking questions if unclear about information provided.

I have to keep the GP informed all the time and I am always questioning him about medication (Interview 2, female patient with complicated migraines)

Coordinating one's care was another activity identified as part of the patient‐as‐professional role, with some participants stating that it is their role to lead and coordinate the interprofessional team. As part of this, participants emphasized the importance of keeping a hand‐held record of their medications, medical appointments and test results. These records enabled them to coordinate the multiple clinicians involved in their care and provide information that clinicians may not have access to. Participants often reported that their clinicians did not work together as a team. As a result, they felt it was their responsibility to summarize the overall context of their condition and its treatment to each clinician, to ensure all team members were working towards a common goal.

The patient sees the ‘big picture’ and the whole team. This is because he or she is constantly dealing with one person after another (Interview 5, female patient with Type 1 diabetes and chronic fatigue)

Part of coordinating one's care was also identified as finding clinicians to be part of the interprofessional team. Some patients reported needing to go to several different clinicians to find one who met their expectations in terms of the level of information that they provide and their willingness to engage in discussion about management options. It was identified as important for clinicians to provide care in a partnership approach that engages patients in the interprofessional team.

Participants highlighted the need for a support network, such as family and friends, to assist in participating in the interprofessional team. They explained that at appointments they may be unable to absorb all the information or remember to ask the necessary questions. Therefore, taking a friend or family member assisted them to gather the information they needed to engage with the team in making decisions about their care. In addition, participants described the importance of networking with other people who have a chronic disease to learn about different management strategies that they could use or present to the team.

You should make visits with another person, a partner or someone, so one person is talking to the doctor and the other one's listening and assessing and says ‘oh you've forgotten something’ or ‘what about this?’ (Focus group 3, male carer and patient with lumbar spondilosis and post‐traumatic stress disorder)

Linked with the need to have a support network was the necessity to find a clinician, family member or someone else to advocate for their needs within the interprofessional team when they are unable to. They explained that this was necessary because having an active collaborative role in one's care can be complex and tiring, particularly when unwell. The role of the advocate was described as focusing on the person's overall health by ensuring that the information and recommendations received from different members of the team is consistent and works towards common goals.

You need an advocate for your health. They [the advocate] need to look at the big picture, rather than the individual aspects, such as increasing one drug (Interview 10, male patient with a cardiac condition)

Influencing factors

The experience of engaging in the interprofessional team to enact the patient‐as‐professional role was reported by participants to be shaped by the patient–clinician relationship; benefits; barriers; and applicability. The patient–clinician relationship was identified as essential to enabling the patient‐as‐professional to be part of the interprofessional team. Participants explained that they needed to find a doctor who would involve them in decision making by communicating openly and taking a holistic approach to providing health‐care advice and treatment options.

Interaction between patient and professional is very important because just to say ‘you take this pill, etc’ that really does you no good at all (Interview 6, male patient with diabetes, Parkinson's and congestive heart failure)

Participants identified factors impacting on the development of a strong patient–clinician relationship, which supported the patient's inclusion in the interprofessional team. In particular, it was thought that clinicians’ time constraints and the lack of coordination between clinicians were barriers.

The benefits of engaging in the interprofessional team by enacting the patient‐as‐professional role were perceived as increased patient awareness of care possibilities and improved care coordination. Participants explained that they could bring valuable knowledge about the impact of their condition on their life to the decision‐making process. By sharing this information and engaging in a collective decision‐making process, participants believed their capacity and confidence in managing their chronic disease increased. They also described that the coordination of their care improved by being actively engaged in the decision process when they developed a clear understanding of the care received from all the clinicians with whom they worked. This was seen to enable them to be the link between their clinicians and, in a sense, to manage their health‐care team.

The patient sees all the professionals dealing with them as a team and they have a broad awareness of how each professional fits into the team. The patient kind of manages the team (Interview 5, female patient with Type 1 diabetes and chronic fatigue)

Concerns were raised that if patients engage in the interprofessional team, clinicians may be unrealistic and expect that all patients would have a high level of involvement in their care. Participants also wondered whether clinicians would have time and the willingness to support higher levels of patient engagement.

Not all doctors have the time for it, or they don't respect the patients enough (Interview 8, female patient, chronic condition not specified)

Some participants questioned the applicability of the patient‐as‐professional role. They believed that as clinicians have completed formal training that they should be responsible for managing the health‐care team and determining the best treatment option. It should not be necessary for patients to be part of this team. Conversely, it was argued that patients should not always have to ask questions, but clinicians should proactively share information.

People say that you need to ask more questions of practitioners, but really, sometimes you don't have a chance to or you don't feel up to it. I believe that it is their role to share information; you shouldn't always have to ask (Interview 5, female patient with Type 1 diabetes and chronic fatigue)

Other participants were in favour of the patient‐as‐professional role. The knowledge about their own experience of chronic disease was recognized as valuable to share with the interprofessional team.

There's two levels of knowledge, one of them is that you've done all the research and you know what all the options are and you have some opinions about it. That's one sort of knowing or professionalism. But the other one is just knowing about your own body. So that even if you don't have any solutions, if you can go to a doctor and articulate your own experience, then that's an input which you can call, in a sense, patient‐as‐professional (Focus group 7, female patient with diabetes, arthritis and chronic fatigue)

Participants believed that not all clinicians nor all patients may support the inclusion of the patient in interprofessional teams. It was considered important that clinicians recognize and respect the decision of patients and carers who may not desire this level of engagement.

Phase 2: Clinician perspectives

Fourteen clinicians working in hospital and community settings were interviewed (see Table 3 for participant characteristics). Interviews varied in length between 40 and 120 min (mean = 62 min).

Table 3.

Clinician characteristics

| Characteristics | Participants |

|---|---|

| Gender (n) | |

| Male | 2 |

| Female | 12 |

| Profession (n) | |

| Nursing | 5 |

| GP | 4 |

| Physiotherapy | 2 |

| Exercise physiology | 1 |

| Fitness instruction | 1 |

| Social work | 1 |

| Length of time working in health industry | |

| 0–5 years | 3 |

| 6–10 years | 1 |

| 11–20 years | 4 |

| 21 years and over | 6 |

| Length of time supporting self‐management | |

| 0–5 years | 7 |

| 6–10 years | 2 |

| 11 years and over | 5 |

Analysis of clinician experience and perspectives of the inclusion of patients in interprofessional teams identified four major themes. These comprised the patient's role, the clinician's role, the importance of the clinician–patient relationship and ramifications of the patient‐as‐professional role (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinician perspectives of the patient‐as‐professional role

| Theme | Sub‐theme |

|---|---|

| The patient's role | Contributing information |

| Determining level of involvement | |

| The clinician's role | Providing on‐going support, guidance and management |

| Targeting information to the individual patient | |

| Encouraging patients to be involved in their care | |

| Importance of the clinician–patient relationship | Working together |

| Maintaining relationship with GPs | |

| Acknowledging patient's experiences and preferences | |

| Ramifications of the patient‐as‐professional role | Positive and negative outcomes |

| Makes consultations more difficult | |

| Too much responsibility for patients? | |

| Factors influencing the achievement of positive outcomes |

The patient's role

Clinicians stated that part of the patient's role in enacting the patient‐as‐professional was contributing knowledge. In particular, information related to the patient's experience of their chronic disease and its management, as well as their priorities for care, were described as valuable contributions.

They know their journey and the whole story. They can shed light on aspects that may be unknown by us and the medical team (Interview 19, female, exercise physiologist)

Clinicians highlighted that it is the patient and carer's responsibility to determine the level of engagement they have in their care. They explained that this decision may vary over time and some patients may choose not to be actively involved or follow their clinician's advice. It was emphasized that patient's preferences for level of involvement in their care and the informed decisions they make need to be respected and considered when identifying treatment options.

Health professionals can advise and advise and advise – but at the end of the day it is the patient who chooses whether to follow through with the advice or not (Interview 26, female, nurse at a GP practice)

The clinician's role

Clinicians identified three areas in which they believed that they supported patient engagement in the interprofessional team. Participants reported supporting patients to solve problems and follow up with clinicians. It was considered especially important that this support was provided long‐term, not just on a single occasion.

Self‐management is the way it should go but for it to be successful the person needs support and advice (Interview 16, female, physiotherapist)

The need to target information to the level desired by each individual patient was identified as important for supporting patients to engage in the interprofessional team. Participants explained that some patients and carers treat clinicians as experts and expect them to have the required knowledge to guide them in solving patient problems, whereas others desire minimal information. Nevertheless, clinicians described it as important to support all patients and carers to participate to some degree in decision making because this contributes to the treatment's success.

If the patient is not involved in the decision‐making then the program [no specific program, the self‐management approach in general] will not be successful (Interview 16, female, physiotherapist)

Participants reported encouraging patients to be actively involved in their care and the interprofessional team by supporting them to ask questions; keep information about their chronic disease and care received; and be involved in decision making. Participants emphasized the need to remind patients and carers, particularly older patients, about how they can be involved and actively manage their chronic disease.

But with the elderly they require encouragement and reminders (Interview 13, female, nurse in a clinical care coordinator role)

Clinician–patient relationship

Clinicians emphasized the need to develop a strong clinician–patient relationship to support patient engagement in the interprofessional team. Specifically, they described the importance of working collaboratively with patients and carers, as well as developing a strong relationship based on trust.

It is all about the client developing trust in the relationship (Interview 20, female, fitness instructor)

Some clinicians admitted that the relationship between patients and GPs is often poor and impacts on the ability of patients to engage in their care. This was thought to be partly due to the lack of time patients and GPs spend together. It was claimed that other clinicians working with the team often had to facilitate communication between the GP and the patient, as well as support patients to engage in the interprofessional team.

There is not enough time with the GP and often patients have a poor relationship with the GP (Interview 13, female, nurse in a clinical care coordinator role)

It was viewed as ‘normal practice’ for non‐GP clinicians, such as physiotherapists or nurses, to work in partnership with patients, and therefore support their engagement in care processes. Clinicians frequently reported acknowledging the experiences and preferences of patients.

It's a given that we will treat patients as experts. (Interview 25, female, social worker)

Ramifications of the patient‐as‐professional role

Clinicians explained that the involvement of patients and carers in the interprofessional team supports them to become more assertive, confident and knowledgeable. In addition, patients and carers may be able to participate more in discussion and decision‐making.

The more education they are given, the more actively involved in their healthcare they can be (Interview 19, female, exercise physiologist)

However, some clinicians were concerned that patients who take on the patient‐as‐professional role would result in the need for longer consultations, impacting on busy professionals and clinics. Additionally, clinicians needed to be up to date with the breadth of information available on each condition, including those management strategies that do not have an evidence base. They explained that consultations may need to be longer because patients would want to discuss information that they have located and ask more questions.

It can make it trickier actually, in the sense that when the patient comes to the consultation they have more preconceived ideas. The consultation tends to go on for longer as you need to discuss the evidence and their understanding (Interview 22, male, GP)

Whether or not this engagement translated into increased compliance with care plans remained an unresolved point. There was the experience that patients and carers who were less engaged were generally more compliant with medication regimes. Additionally, some participants believed that the patient‐as‐professional role is too much responsibility for some patients and carers. Clinicians worried that the role may encourage some patients to think that they have to be in control of their care and the interprofessional team and this may be overwhelming.

Over the years we have been expecting more and more from our clients. I think it has gone too far actually… she [a patient] felt that not only was she managing the emotional aspect of her condition, but also she had to manage all the more medical sides too. She didn't want her family doing it either as she wanted her family to be her family not her carers (Interview 25, female, social worker)

Finally, several factors underpinning effective patient engagement were identified. These included the need for patients to have an appropriate level of medical knowledge and understanding of the health‐care system. Communication skills and the capacity to negotiate with a variety of health professionals were also necessary, as well as the motivation to do so. It was thought that such skills and capacities were not present in many patients.

Patients generally don't have the technical or medical knowledge to contribute [to decision‐making]. That's what they look for from us (Interview 13, female, nurse in a clinical care coordinator role)

Discussion

This study identified characteristics of enacting the patient‐as‐professional role, outlining how patients actively engage in interprofessional care. The study also considered the perspectives and experiences of patients, carers and clinicians in relation to this type of engagement, highlighting where supports and services can be enhanced to promote the patient‐as‐professional role in interprofessional teams.

Characteristics of the patient‐as‐professional role

The ideal patient‐as professional is an individual who is educated about their condition(s) and symptoms and able to articulate their health experiences; keep a health record; identify a support network and health advocate; discuss, negotiate and decide on care plans for themselves with clinicians from a range of professional backgrounds; and coordinate, as necessary, the interprofessional team. Implementing this role in practice is influenced by the patient–clinician relationship, changes in the patient's health status, realization of benefits, overcoming of barriers and individual applicability. Characterized in this way, it highlights the high expectations and complexity of the task (including the high level of health literacy required), and the on‐going challenge associated with its realization. However, if we are to realize patient‐centred care and the benefits of patient empowerment,4, 5 this is what we are seeking to implement.

Support for the patient‐as‐professional role

The majority of participants indicated support for this role, explaining that including the patient‐as‐professional in interprofessional teams would promote the delivery of context‐appropriate and patient‐centred care. As has been described in the literature, it was recognized that patients and carers could contribute valuable information about the lived experience of their condition and play an integral role in care planning.8 In fact, many patients and carers described striving to engage with the interprofessional team and, at times, the barriers that they encounter.

However, it should be noted that not all participants were supportive of the inclusion of the patient‐as‐professional in the health‐care team. Some reported that it was the clinician's role to manage their care. In addition, some clinicians expressed concern that the patient‐as‐professional concept places too much responsibility on some patients. How to allow time, within busy clinics, to provide information and answer questions from those actively involved remained an unresolved issue.

The fact that not all patients desire the same level of involvement in their care is reflective of current literature describing that patients engage in their health care at different levels, ranging from active to passive, informed to uninformed and positive or negative participants.9, 10 This suggests that methods, acknowledging the varying levels at which individuals may wish to be involved in their care, need to be continually considered and discussed with individual patients. There is not one answer that fits all patients in any one clinical area. Discussing with patients the patient‐as‐professional role is an avenue to assist patients to effectively engage with the interprofessional team. Such discussions might also identify where supports and services could be enhanced to overcome the barriers to the patient‐as‐professional role. This will support patients, who desire so, to be empowered to participate in the management of their health and achieve the described benefits of patient empowerment.4, 5

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the sample size of patients, as well as the inclusion of both patients and clinicians to understand the involvement of the patient‐as‐professional in interprofessional teams. However, the small number of carers may be considered a limitation for capturing the perspectives of this group.

It may be viewed as a limitation that this study predominantly recruited participants from a self‐management programme. However, the purposive selection of these participants enabled a rich understanding to be obtained of the experiences of, and strategies for actively engaging in, interprofessional care by enacting the patient‐as‐professional role.

Three researchers were involved in the analysis, ensuring that different perspectives were considered and discussed throughout the process. These researchers also collected data, which assisted them to become familiar with the data.

Conclusion

This study has advanced the understanding of how patients engage in interprofessional health‐care teams by enacting the patient‐as‐professional role and the findings demonstrate that support exists for acknowledging the role in interprofessional teams. The characteristics of the role and factors that influence its enactment could be used to guide patient engagement with the team and could be used by clinicians to support the delivery of patient‐centred care.

The inclusion of the patient‐as‐professional role has the potential to improve health‐care delivery by promoting the delivery of context‐appropriate and patient‐centred care. To achieve the full potential, patients and carers require support from clinicians to identify the most effective strategies they can use to participate in the interprofessional team and in doing so also build their health literacy as required. It is important that this support be tailored to the level of involvement that the person wishes to have in their care. Supporting the patient‐as‐professional will enable time‐poor clinicians to tap into an under‐used resource.

Sources of funding

Australian Department of Health and Ageing, Sharing Health Care Initiative Grant.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank participants involved in this study; community and health representatives for their assistance with recruitment; and Jenny Cahill and Anne Huang for assistance with data collection.

References

- 1. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the Chronic Care Model, Part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2002; 288: 1909–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Effective Clinical Practice, 1998; 1: 2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self‐management of chronic disease in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2002; 288: 2469–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams KE, Bond MJ. The roles of self‐efficacy, outcome expectancies and social support in the self‐care behaviours of diabetics. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 2002; 7: 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Irwin RS, Richardson ND. Patient‐focused care: using the right tools. Chest, 2006; 130: 73S–82S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2006; 166: 1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coulter A. Paternalism or parternship? Patients have grown up‐ and there's no going back. BMJ, 1999; 319: 719–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gruman J, Rovner MH, French ME et al From patient education to patient engagement: implications for the field of patient education. Patient Education and Counseling, 2010; 78: 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maibach EW, Weber D, Massett H, Hancock GR, Price S. Understanding consumers’ health information preferences: development and validation of a brief screening instrument. Journal of Health Communication, 2006; 11: 717–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. UltraFeedback. Report One: Healthy Australia: Seeking better options 2008. Melbourne, Vic.: UltraFeedback, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Henwood F, Wyatt S, Hart A, Smith J. ‘Ignorance is bliss sometimes’: constraints on the emergence of the ‘informed patient’ in the changing landscapes of health information. Sociology of Health and Illness, 2003; 25: 589–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gardiner R. The transition from ‘informed patient’ care to ‘patient informed’ care. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 2008; 137: 241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Detmer DE, Singleton PD, MacLeod A, Wait S, Taylor M, Ridgwell J. The Informed Patient Study: Report Summary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Health, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barnoy S, Volfin‐Pruss D, Ehrenfeld M, Kushnir T. Nurses attitudes towards the informed patient. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 2009; 146: 396–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lorig K. Partnerships between expert patients and physicians. Lancet, 2002; 359: 814–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Department of Health . The Expert Patient: A New Approach to Chronic Disease Management for the 21st Century. London: Department of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lindsay S, Vrijhoef HJM. A sociological focus on ‘expert patients’. Health Sociology Review, 2009; 18: 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaw J, Baker M. “Expert patient” – dream or nightmare? BMJ, 2004; 328: 723–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nugus P, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, Westbrook J, Braithwaite J. How and where clinicians exercise power: interprofessional relations in health care. Social Science and Medicine, 2010; 71: 898–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sheehan D, Robertson L, Ormond T. Comparison of language used and patterns of communication in interprofessional and multidisciplinary teams. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2007; 21: 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. D'Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: an emerging concept. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2005; 19: 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenfield D, Nugus P, Travaglia J, Braithwaite J. Factors that shape the development of interprofessional improvement initiatives in health organisations. BMJ Quality and Safety, 2011; 20: 332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenfield D, Nugus P, Travaglia J, Braithwaite J. Auditing an organization's interprofessional learning and interprofessional practice: the Interprofessional Praxis Audit Framework (IPAF). Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2010; 24: 436–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jowsey T, McRae IS, Valderas JM et al Time's Up. Descriptive epidemiology of multi‐morbidity and time spent on health related activity by older Australians: a time use survey. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8: e59379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pickard S, Rogers A. Knowing as practice: self‐care in the case of chronic multi‐morbidities. Social Theory and Health, 2012; 10: 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Howe A. Can the patient be on our team? An operational approach to patient involvement in interprofessional approaches to safe care. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 2006; 20: 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greenfield D, Nugus P, Fairbrother G, Milne J, Debono D. Applying and developing health service theory: an empirical study into clinical governance. Clinical Governance: An International Journal, 2011; 16: 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Short A, Phillips R, Dugdale P, Nugus P, Greenfield D. Evaluating the Impact of the ‘Patient‐As‐Professional Within a Network’ Tool to Self‐Manage Chronic Disease: Research Outputs. Canberra, ACT: ANU and UNSW, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practial Guide for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL et al Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self‐management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Medical Care, 1999; 37: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abbott S, Vassallo A, Dugdale P, Greenfield D. Training Group Leaders How to Include People with Chronic Disease in Community Activities. Canberra, ACT: ANU eView, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Phillips RL, Short A, Dugdale P, Nugus P, Greenfield D. Supporting patients to self‐manage chronic disease: clinicians’ perspectives and current practices. Australian Journal of Primary Health. doi: 10.1071/PY13002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liamputtong P. Qualitative data analysis: conceptual and practical considerations. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 2009; 20: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liamputtong P. Qualitative Research Methods, 3rd edn Sydney, NSW: Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Data management and analysis methods In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y. (eds) Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Thousands Oaks, CA: SAGE, 1998: 259–309. [Google Scholar]