Abstract

Objective

To synthesise the views of patients on patient‐held records (PHR) and to determine from a patient's perspective the effectiveness and any benefits or drawbacks to the PHR.

Design

Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies, which investigate the perspective of patients on the effectiveness of the PHR.

Data sources

Medline, CINAHL, PsychINFO, PubMed, Cochrane.

Review methods

Systematic review of literature relevant to the research question and thematic synthesis involving line by line coding of the quotations from participants and the interpretations of the findings offered by authors.

Results

Ten papers that reported the experiences of 455 patients were included in the thematic synthesis. Five studies focused on cancer care, two on mental health, one on antenatal care, one on chronic disease and one on learning disability. The completeness of reporting was variable. Three main themes were identified: (i) practical benefits of the PHR (having a record of one's condition, an aide memoire, useful information source and tool for sharing information across the health system); (ii) psychological benefits of the PHR (empowered to ask questions, a place to record thoughts and feelings and feeling in control); and (iii) drawbacks to the PHR (PHR imposes unwanted responsibility and ineffectiveness).

Conclusions

The effectiveness of the PHR is largely dependent upon uptake across the health system from patients and health‐care providers alike. Robust qualitative studies are needed, which offer more complete reporting and examine what patients want and need from a PHR.

Keywords: effectiveness, patient's perspective, patient‐held record

Introduction

The patient‐held record (PHR) has been used widely across health‐care systems in a variety of health‐care contexts such as chronic disease,1, 2 cancer care,3, 4, 5, 6 mental health7, 8 and antenatal care.9, 10 Within each context, it aims to provide a personal health‐care record for the patient and facilitate communication between patients and health professionals.4 More specifically, the PHR is viewed as an inexpensive, practical intervention that can help improve quality of care by involving patients in the management of their condition, providing them with information and ensuring that their health‐care record is available to all health professionals they consult.11 However, its success has been variable, and reports on its effectiveness have often been equivocal.4, 12 This may reflect an uncertainty among patients and health professionals about the intended function of the PHR, which would complicate the measurement of outcomes.

Large trials of the PHR have reported outcome measures in terms of service satisfaction12 and satisfaction with information and communication.13, 14 In two of these studies, the findings were ambivalent.12, 13 There was little reported difference in communication outcomes13 or satisfaction with services12 between those who received a PHR and those who did not. Equally, the majority of patients asked found the PHR helpful and of value.12, 13 The third study reported that the PHR generated some anxiety amongst patients alongside no measurable benefits.14

One study using questionnaires and focus groups reported that patients were very positive about the PHR as a user‐friendly means of sharing patient‐specific information and facilitating communication.6 Another found the PHR to have disappointing evaluations, which showed little or no impact on the communication passing between health‐care professionals.15

Three systematic reviews of the use of PHRs in health care have been identified in the literature.4, 16, 17 One review examined the effectiveness of the PHR in cancer care,4 another considered the potential benefits of a PHR for undocumented immigrants16 and the third17 was a Cochrane review of PHRs for people with severe mental illness, although no study met the inclusion criteria for the review. In the systematic review on PHRs in cancer care, it was concluded that whilst patients felt more involved in their care as a result of the PHR, there was a lack of understanding over its function.4 In the systematic review of the PHR for undocumented immigrants,16 the use and appreciation of PHRs by patients was deemed overall to be satisfactory, but there was variable opinion towards their use in individual studies, some reporting a preference by patients not to have one. Usage of the PHR in general varied from 44 to 93% and was different between patient groups, lower usage reported in mental health compared with cancer care, for example. In the review, this difference was explained by how much each group valued information and communication.16

Patient opinion, satisfaction and use of the PHR were considered in these reviews, but they did not focus specifically on an evaluation of the perceived value and experience of using of the PHR from the patient perspective. Other individual studies of the effectiveness of the PHR report no impact on communication between patients and health‐care professionals and no measurable patient benefit.13 Furthermore, the PHR does not always get used,16, 18, 19, 20 and there is reported failure to embed into clinical practice.12

Patient factors are critical to the acceptance and use of a PHR. The PHR is primarily a local tool, sometimes developed in consultation with a local user group.7, 21 However, it seems only a limited number of published studies have to date used qualitative methods to appraise and evaluate the effectiveness of the PHR from a patient's perspective.

The majority of published research has focused on the paper format PHR. However, the concept of digitised health record‐keeping is already in the public sphere, and personal digital assistant (PDA) technology is widely available.22, 23 In the UK National Health Service, electronic PHRs are now being developed, purporting to allow patients greater control over managing their health‐care appointments and information,24 which are core aspects of self‐management of conditions. Few empirical studies of these exist as yet, which consider the patient's perspective. However, one recent study of an interactive health communication application for cancer patients in Norway identified ambivalence amongst users, and it was valued more by high‐frequency users.25

We aimed to conduct a systematic review and thematic synthesis26, 27, 28, 29 of qualitative studies of patients' views of the PHR in health care to understand the patient factors that contribute to its effectiveness.

Methods

Search strategy

The aim of the review was to gather and analyse the evidence on patients' views of the PHR and to understand the patient factors that contribute to its effectiveness. Search terms were chosen by the research team and included the MeSH terms ‘patient‐held record,’ ‘care record,’ ‘data bank,’ ‘PHR,’ ‘client held’ and ‘patient experience’. We also searched under text words ‘health‐care documents,’ ‘information resources’ and ‘medical record linkage’. These were all the terms under which the PHR was known to the authors at that time. The search mode was Boolean/Phrase. All searches were combined with ‘and’ to ensure they were as inclusive as possible. We carried out searches through EBSCO Host in CINAHL Plus with Full Text (1982 to March week 4 2013), MEDLINE (1950 to March week 4 2013), PsycINFO (1597 to March week 4 2013), PsycARTICLES (1894 to March week 4 2013) and the Cochrane Library (1995 to present). The search strategy was broad to yield the maximum number of studies, and no date limit was set. We supplemented this search strategy by checking the reference lists of all retrieved articles for additional articles. To select studies for further assessment, one of the authors (SS) reviewed the title and abstract of every record retrieved. Articles were selected if this information indicated that the study met our eligibility criteria. If there was doubt regarding the title and abstract information, the full article was retrieved for clarification. The research team (all three authors SAS, SS, JP) then examined the remaining full text reports independently for eligibility criteria with one author (JP) arbitrating over differences.

Eligibility criteria and literature search

We included studies that utilised qualitative methods (face‐to face or telephone interviews or focus groups) to explore the patient experience of PHRs. A patient was defined as an adult who had been issued with a patient‐held record. We excluded studies, which focused on solely the views of health‐care professionals/staff and those which focused solely on the views of carers or relatives of the patient issued with a PHR. Primary research studies only were included.

Comprehensiveness of reporting

Two researchers (SAS and SS) assessed independently the reporting of selected studies using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).30 The senior analyst (SAS) reviewed the overall consistency and accuracy of reportage.

Synthesis

The authors followed approved methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews.26, 27 In stage one of the thematic synthesis, all verbatim quotations from participants and all authors’ verbatim interpretations of the findings in each study were identified. Study by study, the data and text were entered into a visual matrix for ease of coding line by line. Two reviewers (SS and SAS) coded independently each line of text. The initial ‘free coding’ generated 26 codes. Stage two involved generating descriptive themes from the free codes and finally analytical themes which would capture the essence of the free codes and descriptive themes.

Results

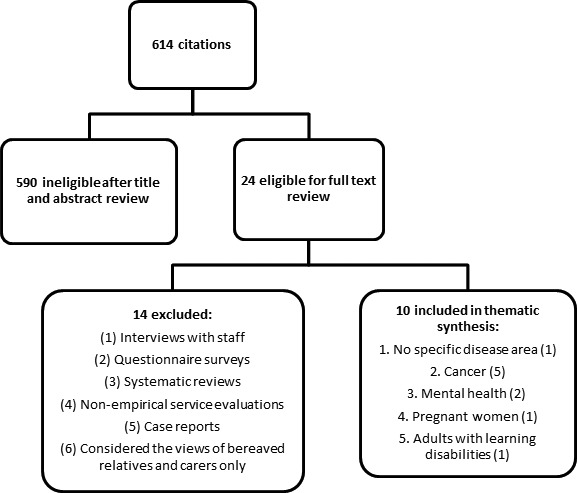

The search yielded 614 citations (see Fig. 1). Of these, 590 were ineligible after review of the title and abstract. Of the remaining 24 studies, 14 were excluded for the following reasons: (i) involved solely interviews with staff (n = 2); (ii) involved questionnaire surveys only (n = 5); (iii) were systematic reviews (n = 3); (iv) were non‐empirical service evaluations (n = 2); and (v) case report (n = 1) or (vi) considered the views of bereaved relatives and carers only (n = 1). Ten papers that reported the experiences of 455 patients were included in the thematic synthesis.2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 13, 14, 31, 32, 33

Figure 1.

Results of search and review of eligible studies.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study reference | Country (Region) | Context | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Australia (Sydney) | Chronic disease | Semi‐structured interviews with 10 patients to elicit views on whether using a PHR they could contribute to improvements in their care |

| 3 | UK (Swansea) | Patients with cancer in the community | 303 telephone interviews with patients about their preferences regarding the patient‐held record using a semi‐structured questionnaire |

| 5 | UK (Glasgow and Edinburgh) | Advanced cancer and palliative care | 74 of 80 patients randomised to receive a PHR were interviewed about their use of the record |

| 6 | UK (York) | Cancer: breast, haematological, colorectal and lung | 9 patients took part in a focus group interview about a PHR for cancer care |

| 7 | UK (Wakefield) | Mental health | 10 PHR users were interviewed face‐to‐face on the experience of PHR following completion of pilot |

| 13 | UK (Newcastle‐upon‐Tyne) | All types of cancer at any stage of the disease | 8 patients provided with a PHR at diagnosis participated in a follow‐up telephone interview |

| 14 | UK (Oxford) | Far advanced cancer needing palliative care | In‐depth, semi‐structured personal interviews. 34 patients completed a first interview and 30 completed a second |

| 31 | Australia (Sydney) | Antenatal care | 21 participants were interviewed a face‐to‐face and asked open‐ended questions about the advantages and disadvantages of carrying their records |

| 32 | UK (Manchester) | Learning disability | Follow‐up interviews were carried out with 4 of 7 clients who had agreed to use a client held health record (CHHR) for approximately 3 months |

| 33 | UK (East London) | Long‐term mental illness | A short semi‐structured face‐to‐face interview consisting of seven questions. Interviews were conducted with 45 patients of the total sample |

PHR, patient‐held records.

Comprehensiveness of reporting of included studies

The completeness of reporting was variable across the studies (see Table 2). In six out of ten studies, it was not possible to discern which, if any of the authors, undertook the interviews or focus groups. In nine studies, the experience and training of the research team was neither reported nor discernible. In only one study,2 a qualitative sampling strategy (theoretical sampling) had been explicitly reported. In eight studies, major themes were clearly represented in the findings. In two studies7, 33 a summary description of findings was provided, but themes were not highlighted. Strategies to enhance the reliability of study findings were variable, and in general, most studies had weaknesses in this respect. For example, nine studies did not state how many coders coded the data; no studies reported returning transcripts to the participants, and only two studies stated if audio/visual recording had been used. Only four studies included quotations from participants.

Table 2.

Comprehensiveness of reporting assessment – assessed using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research checklist30

| Reporting criteria | No of studies reporting criterion | References of studiesa |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of research team | ||

| Interviewer or facilitator identified | 4 | 7, 13–14, 32 |

| Credentials (BSc, PhD) | 5 | 13, 7, 32, 2, 33 |

| Occupation | 5 | 13–14, 3, 32–33 |

| Sex | 7 | 13, 5, 14, 7, 32, 2, 33 |

| Experience and training | 2 | 13–14 |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| Relationship established before study started | 4 | 13, 6, 7, 33 |

| Participant knowledge of interviewer | b | – |

| Methodological theory identified | ||

| Participant selection | ||

| Sampling | 1 | 2 |

| Method of approach | 7 | 2–3, 7, 13–14, 32–33 |

| Sample size | 10 | 2–3, 5–7, 13–14, 31–33 |

| Non‐participation | 8 | 3, 5, 7, 13–14, 31–33 |

| Setting | ||

| Setting of data collection | 7 | 3, 5, 7, 13, 14, 31, 33 |

| Presence of non‐participants | 1 | 34 |

| Description of sample | 9 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 13, 14, 31–33 |

| Data collection | ||

| Interview guide | 6 | 2, 3, 5, 7, 14, 33 |

| Repeat interviews | 3 | 13, 5, 14 |

| Audio/visual recording | 2 | 6, 31 |

| Field notes | 1 | 14 |

| Duration | 1 | 31 |

| Data saturation | 0 | – |

| Transcripts returned | 0 | – |

| Data analysis | ||

| Number of data coders | 1 | 31 |

| Description of the coding tree | 1 | 31 |

| Derivation of themes | 8 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 13–14, 31–32 |

| Software | 2 | 2, 3 |

| Participant checking | 0 | – |

| Reporting | ||

| Quotations presented | 4 | 2, 6, 7, 13 |

| Data and findings consistent | 6 | 2, 6, 7, 13 |

| Clarity of major themes | 8 | 2–3, 5–7, 13–14, 32 |

| Clarity of minor themes | 2 | 5, 14 |

As they appear in the reference list of this publication.

Unknown in all cases.

Synthesis of findings

Three major themes were derived from the thematic synthesis: (1) practical benefits of the PHR (having a record of one's condition, an aide memoire, useful information source and tool for sharing information across the health system); (2) psychological benefits of the PHR (empowered to ask questions, a place to record thoughts and feelings, feeling in control); and (3) drawbacks of the PHR (PHR imposes unwanted responsibility, and ineffectiveness). Table 3 lists the studies that reported or discussed each theme, and Table 4 provides a selection of quotes from participants (where quotes were present), accompanied by authors' interpretations of the raw data.

Table 3.

Themes identified in each study

| Themes | Study reference | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 14 | 32 | 33 | 34 | |

| Practical benefits of the PHR | ||||||||||

| Having a record of one's condition | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | – | – | Yes |

| An aide memoire | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | Yes |

| Useful source of information for the patient | Yes | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes |

| Tool for sharing information across the health system | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Psychological benefits of the PHR | ||||||||||

| Empowered to ask questions | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | Yes | – | – |

| A place to record thoughts and feelings | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | – | – | – | – |

| Feeling in control | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | – | – |

| Drawbacks of the PHR | ||||||||||

| PHR imposes unwanted responsibility | – | – | Yes | – | – | – | Yes | – | Yes | Yes |

| Ineffectiveness | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | – | Yes | Yes |

PHR, patient‐held records.

Table 4.

Quotations from participants (where available) with authors' interpretations

| Theme | Quotation from participants | Author's interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Practical benefits of the PHR | ||

| Having a record of one's condition | ‘I keep a record of chemotherapy, scans and X‐rays’. (study Ref. 6) | ‘Comments from patients indicated that the record had been used in many different ways…as a chronological record of treatment, symptoms and recovery’ (study Ref. 6) |

| ‘It's got quite a lot of everything in…it's got places to put my hospital cards in, about my prescriptions, all my dates and numbers’ (study Ref. 7) | ‘…the record found value as a diary, as a source of information, and as a place to keep a copy of the CPA care plan…’ (study Ref. 7) | |

| An aide memoire | ‘It keeps you in touch with your progress, especially when you can't rely on your memory’ (study Ref. 13) | ‘Comments on ways that the PHR could be useful in the future included having a record to refer to of what had happened previously’ (study Ref. 13) |

| ‘It has been helpful because with my age I get forgetful and if anyone asks me I can refer to it’ (study Ref. 13) | ||

| Useful source of information for the patient | ‘I can take information in and understand it more’ (study Ref. 13) | ‘Fifty six percentage of respondents felt that the PHR had kept them informed’ (study Ref. 13) |

| Tool for sharing information across the health system | ‘If I was on holiday or maybe overseas, and I could walk in with it and I had a problem they could help me quicker than having to go through all the tests and things’ (study Ref. 2) | ‘The benefit of having an accurate medical history with them when they changed medical practitioners was mentioned by Margaret, Trevor, Pauline and Juan’ (study Ref. 2) |

| ‘It's a history of the illness. If anyone wants to know what's happened then I can hand it to them’ (study Ref. 6) | ‘Those health professionals who had used the record with patients highlighted the importance of having a access to a record of treatment medications and commented they were good as a resource to pass information back and forth and very useful when lots of disciplines are involved’ (study Ref. 6) | |

| 2. Psychological benefits of the PHR | ||

| Empowered to ask questions | ‘I can ask questions about the blood – the significance of them going up and down’ (study Ref. 13) | ‘It was felt that being given the record at this time gave patients the opportunity to look at its content, to digest suggested questions for discussion with their medical team’ (study Ref. 13) |

| A place to record thoughts and feelings | ‘The health diary is a big help – I was so angry, it helped to write it down’ (study Ref. 6) | ‘The quotes and comments from users demonstrate a positive reaction to the record…highlight the value for many patients of using writing as a therapeutic tool’ (study Ref. 6) |

| Taking responsibility | ‘You learn to understand your condition and what factors can have influence which is a must. If you don't know, you can't take responsibility or you rely on the doctors’ (study Ref. 2) | ‘Juan mentioned the significance of ‘responsibility’’ (study Ref. 2) |

| Feeling in control | ‘You learn to understand your condition and what factors can have influence which is a must. If you don't know, you can't take responsibility or you rely on the doctors’ (study Ref. 2) | Margaret and Juan mentioned that it was important to them to have some control over their own health (study Ref. 2) |

| 3. Perceived drawbacks of the PHR | ||

| Ineffectiveness | One patient (Patient 14) commented that, ‘not one medical person has ever asked me for it’ and another (Patient 13) that, ‘some people know more about the file than others’ (study Ref. 6) | Patients reported having to ask their doctor or nurse to read and write in their record, rather than vice versa (study Ref. 6) |

PHR, patient‐held records.

1. Practical benefits of the PHR

The theme ‘practical benefits of the PHR’ encompassed the usefulness of the PHR as a concrete, everyday tool for the patient. In seven studies, patients valued having their own record of their condition, and so the PHR was a good source of personal health information, such as the results from tests and scans and details of next appointments. Seven studies also reported that patients valued the PHR as an aide memoire, especially if and when their own memory could not be relied upon. In five studies, having a tool for sharing information across the health system was perceived to be beneficial, facilitating the sharing of medical history and cutting down on the patient's work of repeating it in different contexts to various health providers. Its usefulness as a tool for sharing information was not limited to health providers; the PHR has been used to assist in giving explanations to patients' friends and relatives. For example, the PHR in antenatal care enabled the pregnant woman to share information with her partner and wider family.31

2. Psychological benefits of the PHR

Although less frequently reported, there were psychological benefits associated with having a PHR, and empowerment was one of them. Five studies reported that patients felt more able to ask questions or challenge assumptions, about the results of tests, for example. It was reported that the PHR gave them permission to discuss their illness and treatment more, and so, therefore, they felt more actively involved in their care. Having something to hand, which they could legitimately use as a therapeutic tool for recording their thoughts and feelings, was reported in four studies. In five studies, patients reported a sense of feeling more in control as a consequence of having and using a PHR, helping them to prepare for meetings with health‐care professionals.

3. Drawbacks of the PHR

In four studies, the impact of the PHR was negative, and patients thought that it placed, or could potentially place, the ethical problem of unwanted responsibility their way or on to their informal carer. This was explained in the papers in terms of the differing needs of patients, individual practices around holding own health information and concerns about what taking ownership of the PHR would entail. Additionally, comments about the ineffectiveness of the PHR were highlighted, and eight papers report on some form of perceived ineffectiveness. The subtheme ‘ineffectiveness' encompassed the issue of no local awareness or ownership of the record on the part of clinical staff, patients’ difficulties with getting staff to fill it in, and this impacting on their perception of the effectiveness of the PHR. Patients not using or forgetting to use their PHR were also reported.

Discussion

This thematic synthesis has highlighted the ways in which the PHR is of practical and psychological benefit to patients. It has also drawn attention to the perceived weaknesses of the PHR.

These findings very much reflect the pragmatic approach undertaken in the majority of papers reviewed. The synthesis undertaken shows that the PHR is perceived to be of practical benefit in a range of health‐care contexts, providing the patient with a record of their condition, acting as an aide memoire and a valuable source of information, and leading to some psychological benefits such as empowering the patient to ask questions and facilitating a sense of control. For these reasons, and given the available evidence, the PHR can be said to be effective from a patient's perspective.

The identification of ineffectiveness as a theme within the qualitative synthesis is emblematic of the equivocal findings generally associated with the PHR – it is of potential benefit, but if its intended purpose is not understood by users or if it is not used and not embedded within organisations or across the health system, it quickly ceases to be effective or of value. Therefore, more attention to implementation is necessary. The wider research literature on PHRs informs us that they are not always successful or even effective. The reasons why PHRs fail are largely related to failure in uptake by either the patient12, 34 or the health provider.21, 35 However, in this review, most findings reported were positive and indicative of a strong social desirability bias.

What matters to all patients in receiving care is that they feel informed and receive information and clear explanations of their condition or treatment,36 and the PHR can be an effective adjunct to good communication. Regardless of its function, having a PHR may help patients to get what they want by giving them a crucial starting point for asking questions about their health care, helping them to be better informed about their condition. This is critical to self‐management and patient engagement in health care, although the effect of a PHR on these outcomes is likely to be patient‐specific, being helpful for some but not others. Despite this, paper prototypes of a PHR are unlikely to be sustainable in the future. Current technologies have altered the mode of the PHR so that it is more portable, more user‐friendly and increasingly adaptable to patients’ needs.25

A limited number of studies reported on patients' concerns related to having additional, unwanted responsibility imposed on them as a result of having and using a PHR. That patients who are more passive in decision making do not perceive a need to carry their own health information is a point highlighted in one paper within our review.2 For many patients, in the health system, the burden of treatment is problematic, and they reject more involvement in their care because it does not reflect their values or their preferences.37

The systematic review has shown that the quality of reporting of the patient's experience of the PHR is not comprehensive. More and robust qualitative studies of the patient's experience of the PHR are needed if we are to understand fully the patient's perspective of having and using a PHR. Notably, the majority of papers included in this review do not report use of a theoretical framework to underpin the study, with the exception of one2 reporting the use of grounded theory in exploring the concept of responsibility in patients carrying their own health records. A general theory of implementation38 would provide a robust set of conceptual tools that enable researchers and practitioners to identify, describe and explain important elements of implementation processes and outcomes – processes such as the collective action to put the PHR into practice and continually using it until it becomes normalised.

Study limitations and how they were addressed

Other authors have found that in systematic reviews of qualitative studies involving thematic synthesis of findings, the primary studies that are more comprehensive in their reporting will have most likely contributed more to the final analysis.27 In the present study, only four papers presented quotations from interviews with participants, and so the reviewers relied also on authors' interpretations across all studies. There was good representation of the main themes (e.g. the main practical benefits of the PHR, the reported ineffectiveness of the PHR) in the majority of studies reviewed, regardless of the comprehensiveness of the reporting, so that any one study did not dominate. Nonetheless, the analysis is dependent on the quality and depth of reporting of the primary studies.

It is widely accepted that publication bias can distort findings because studies with more significant results or influential authors are more likely to be published without delay, than those without.39 All efforts were made to be as inclusive as possible during the search process in an attempt to reduce bias. Small stand‐alone studies as well as qualitative studies within larger and more prominent research are reported in this review.

Whilst our focus was on empirical studies (to enhance robustness and reliability), we recognise that not all evaluations of PHRs are conducted as empirical studies, and we identified and excluded three papers that were non‐empirical service evaluations or case reports. The PHR may have been used under different names not yet known to the authors, and we acknowledge this as a limitation to the search strategy. For example, in retrospect, we identified a paper which used the term ‘Interactive Health Communication Application’.25

Suggestions for further research

There is a need for good quality studies of the PHR, which will focus on patients' imperatives. Also, future studies will need to examine fully the potential for the PHR to be burdensome in some contexts.

Previously, the extent to which patients are empowered by the PHR has depended upon their willingness to carry their own health information.2 With the emergence of electronic PHRs,24, 25 different patient factors may affect uptake, not least concerns about the safety and accessibility of electronically held personal information. These factors will need to be brought to light in future qualitative studies.

The absence of a theoretical framework in current publications will need to be redressed in future evaluations and studies of the PHR, and a general theory of implementation38 described previously may be the key to this. Such a theory to underpin future research studies would greatly benefit this body of work, enabling a fuller understanding of the contribution of the PHR across the health system and the health system's capacity for sustaining it.

References

- 1. Hickman M, Drummond N, Grimshaw JA. Taxonomy of shared care for chronic disease. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 1994; 16: 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forsyth R, Maddock CA, Iedema RAM, Lassere M. Patient perceptions of carrying their own health information: approaches towards responsibility and playing an active role in their own health – implications for a patient‐held health file. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 416–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams JG, Cheung WY, Chetwynd N et al Pragmatic randomised trial to evaluate the use of patient held records for the continuing care of patients with cancer. Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10: 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Does the patient‐held record improve continuity and related outcomes in cancer care: a systematic review. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 2007; 10: 75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cornbleet MA, Campbell P, Murray S, Stevenson M, Bond S. Patient‐held records in cancer and palliative care: a randomized, prospective trial. Palliative Medicine, 2002; 16: 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson S, Mayor P. A patient‐held record for cancer patients from diagnosis onwards. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 2002; 8: 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greasley P, Pickersgill D, Leach C, Walshaw H. The development and piloting of a patient held record with adult mental health users. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 2000; 7: 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson N, Sridharan S, Megson M, Patel V. Preventing chronic disease in people with mental health problems: The HEALTH Passport (Helping Everyone Achieve Long Term Health) approach. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 24th Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; Paris France. Conference Start: 03/09/2011 Conference End: 07/09/2011. Conference Publication (var.pagings); 21: S612.

- 9. Webster J, Forbes K, Foster S, Thomas I, Griffin A, Timms H. Sharing antenatal care: client satisfaction and use of the ‘patient‐held record’. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 1996; 36: 11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lovell A, Zander L, James C, Foot S, Swan A, Reynolds A. The St. Thomas's hospital maternity case notes study: a randomised controlled trial to assess the effects of giving expectant mothers their own maternity case notes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 1987; 1: 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dickey LL. Promoting preventive care with patient‐held minirecords: a review. Patient Education and Counseling, 1993; 20: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lester H, Allan T, Wilson S, Jowett S, Roberts L. A cluster randomised controlled trial of patient‐held medical records for people with schizophrenia receiving shared care. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 2003; 53: 197–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lecouturier J, Crack L, Mannix K, Hall RH, Bond S. Evaluation of a patient‐held record for patients with cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 2002; 11: 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drury M, Yudkin P, Harcourt J et al Patients with cancer holding their own records: a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice, 2000; 50: 105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farquhar MC, Barclay SL, Earl H, Grande GE, Emery J, Crawford RA. Barriers to effective communication across the primary/secondary interface: examples from the ovarian cancer patient journey (a qualitative study). European Journal of Cancer Care (England), 2005; 14: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoevers MA, Muijsenbergh METC, Lagro‐Janssen ALM. Patient‐held records for undocumented immigrants: a blind spot. A systematic review of patient‐held records. Ethnicity and Health, 2009; 14: 497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henderson C, Laugharne R. User‐held personalised information for routine care of people with severe mental illness (review). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011; 5: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ayana M, Pound P, Lampe F, Ebrahim S. Improving stroke patients’ care: a patient held record is not enough. BMC Health Services Research, 2001; 1: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Finlay IG, Jones N, Wyatt P, Neil J. Use of an unstructured patient‐held record in palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 1998; 12: 397–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Essex B, Doig R, Renshaw J. Pilot study of records of shared care for people with mental illnesses. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition), 1990; 300: 1442–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bridgford A, Davis TME. A comprehensive patient‐held record for diabetes. Part one: initial development of the Diabetes Databank. Practical Diabetes International, 2001; 18: 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Apple Incorporated . My health record keeper. Available at: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/my-health-record-keeper/id418612831?mt=8, accessed 29 November 2013.

- 23. My Medical . The best iPhone medical record is now on Android too. © 2011. Available at: http://www.mymedicalapp.com/, accessed 29 November 2013.

- 24. University Hospital Southampton . My health record. Available at: http://www.uhs.nhs.uk/AboutTheTrust/Myhealthrecord/Myhealthrecord.aspx, accessed 29 November 2013.

- 25. Grimsbo GH, Engelsrud GH, Ruland CM, Finset A. Cancer patients' experiences of using an Interactive Health Communication Application (IHCA). International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well‐being, 2012; 7: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology, 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. British Medical Journal, 2010; 340: c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dixon‐Woods M, Bonas S, Booth A et al How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective Qualitative Research, 2006; 6: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ring N, Ritchie K, Mandava L, Jepson R. A guide to synthesising qualitative research for researchers undertaking health technology assessments and systematic reviews. NHS Quality Improvement Scotland, 2010; Available at: http://www.nhshealthquality.org/nhsqis/8837.html, accessed 29 November 2013.

- 30. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2007; 19: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Phipps H. Carrying their own medical records: the perspective of pregnant women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2001; 41: 398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kennedy S. An investigation into the practicalities of introducing client held health records to a multidisciplinary community team for people with a learning disability. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 2003; 49: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stafford A, Laugharne R. Evaluation of a client held record introduced by a community mental health team. The Psychiatrist, 1997; 21: 757–759. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davies TME, Bridgford AA. Comprehensive patient‐held record for diabetes. Part two: large‐scale assessment of the diabetes databank by patients and health care workers. Practical Diabetes International, 2001; 18: 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cher L, Matthews M, Byrne K, Simons K, Costantin D, Scott C. Evaluation of a Patient‐Held Record (PHR) for primary brain tumour patients. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009, 36th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Clinical Oncological Society of Australia, COSA Gold Coast, QLD Australia. Conference Start: 17/11/2009 Conference End: 19/11/2009. Conference Publication (var.pagings). 5, A191.

- 36. Department of Health and Institute for Innovations . What matters to patients? Developing the evidence base for measuring and improving patient experience. Final project report, November 2011. King's Fund, London.

- 37. May C, Montori V, Mair F. Analysis ‘we need minimally disruptive medicine’. British Medical Journal, 2009; 339: 485–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. May C. Towards a general theory of implementation. Implementing Science, 2013; 8: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thornton A, Lee P. Publication bias in meta‐analysis: its causes and consequences. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2000; 53: 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]