Abstract

Background

Internet discussion forums provide new, albeit less used data sources for exploring personal experiences of illness and treatment strategies.

Objective

To gain an understanding of how discussion forum participants value nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in smoking cessation (SC).

Setting

Finnish national Internet‐based discussion forum, STUMPPI, supporting SC and consisting of ten free discussion areas, each with a different focus. The analysis was based on STUMPPI forum participants’ postings (n = 24 481) in five discussion areas during January 2007–January 2012.

Design

Inductive content analysis of the postings concerning NRT use or comparing NRT to other SC methods.

Results

Three major themes related to NRT in SC emerged from the discussions. These were as follows: (I) distrust and negative attitude towards NRT; (II) neutral acceptance of NRT as a useful SC method; and (III) trust on the crucial role of NRT and other SC medicines. The negative attitude was related to following perceptions: NRT use maintains tobacco dependence, fear of NRT dependence or experience of not gaining help from NRT use. NRT was perceived to be useful particularly in the initiation of SC attempts and in dealing with physiological dependence. The most highlighted factors of successful quitting were quitters’ own psychological empowerment and peer support from the discussion community.

Conclusions

The majority of STUMPPI forum participants had low or balanced expectations towards the role of NRT in SC. More research from the smokers’ and quitters’ perspective is needed to assess the real value of NRT compared to other methods in SC.

Keywords: internet discussion forum, nicotine replacement therapy, postings, smoking cessation

Introduction

Pharmacotherapy is highlighted as the cornerstone of treatment in smoking cessation (SC) in several clinical guidelines, which primarily base their recommendations on scientific evidence on efficacy.1, 2, 3, 4 Despite the proven efficacy of pharmacotherapy in controlled clinical trials and interventions, SC is a more complicated phenomenon in real life, which may raise the question of the actual effectiveness of SC pharmacotherapy in practice. It is known that quitting without any assistance (i.e. ‘cold turkey’) is far more common than the use of any SC pharmacotherapy.2, 5, 6, 7, 8 There can be several reasons for non‐ or underuse of SC pharmacotherapy (see Table 1). Smokers and quitters may also prefer the use of non‐traditional SC aids or place an extremely strong emphasis on the role of their own willpower in successful SC.11, 12, 30, 45 Further research is needed to gain a better understanding of how smokers and quitters behave in real life and what their SC strategies and decision‐making processes are.

Table 1.

Comparison of the literature on NRT use and discussions from STUMPPI on NRT products use in real life

| Usage patterns (literature of real life use) | Additional usage patterns, emerged from the STUMPPI discussions |

|---|---|

No NRT use

|

No NRT use Cold turkey quitting

|

Use for a short time (brief use)

|

Use for a short time

|

Use for a small dosage

|

Use for a small dosage

|

| NRT combination therapy | NRT combination therapy

|

Use with wrong technique

|

Use with wrong technique

|

Concurrent use of NRT and cigarettes

|

Concurrent use of NRT and cigarettes

|

Dependence on NRT

|

Dependence on NRT

|

|

Long‐term use |

Long‐term use

|

|

To achieve long‐term cessation |

To achieve long‐term cessation

|

Careful plan of NRT treatment

|

Careful plan of NRT treatment

|

|

Misuse of NRT |

Misuse of NRT

|

Internet discussion forums provide a rich source of personal experiences of illness and conditions.46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54 The forums have been considered as a promising component of e‐health, as they provide easily accessible interactive forums with topics originating from participants’ needs.48, 49, 50 In these communities, participants can anonymously share sensitive health issues, express and gain peer support, bring up several informative matters and ask questions. Studies on participants’ experiences of various chronic, rare or life‐threatening conditions alleviate especially their need for informational and emotional support.50, 51, 52, 53 Furthermore, participation can support participants’ empowerment and self‐efficacy, which are two highly important components of permanent lifestyle changes such as SC.2, 50, 52 For researchers, these forums may provide a rich variety of participants’ perceptions, which is not possible to gain by traditional qualitative interviews.54

Despite the existence of a great variety of SC discussion forums, to our knowledge, only two previous studies have explored quitters’ communications in these forums.46, 47 Burri with her colleagues (2006) analysed general topics discussed by ex‐smokers without focusing on any special SC aids.46 Selby's group (2010) focused on the dynamics of interaction and the social support role of the SC discussion forum in Canada.47 No previous study has explored how smokers and quitters describe their use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and its perceived effectiveness in SC in a discussion forum. Our qualitative study aimed at understanding how quitters and smokers valued NRT in SC and how they share their experiences of NRT use in a Finnish national Internet discussion forum for SC. NRT was chosen as the focus of our study because it is the most commonly used SC pharmacotherapy, with easy availability as an over‐the‐counter medicine.9, 55

Methods

Study context

NRT in Finland

In Finland, NRT was introduced as a prescription medicine in 1983.56 During the late 1980s and early 1990s, several NRT drug forms and package sizes were switched to non‐prescription medicines available at pharmacies. After NRT had become a non‐prescription medicine, especially the Association of Finnish Pharmacies had systematically provided education, counselling materials and tools to increase community pharmacists’ involvement in SC, with a special focus on counselling NRT users.56, 57 These systematic efforts to increase Finnish pharmacists’ participation in SC were reflected in the Finnish SC Guideline, published for the first time in 2002.58 According to the guideline, the pharmacists’ role in SC is to counsel, support and guide the rational use of NRT in local multidisciplinary SC teams. In February 2006, NRT products were deregulated to general sales, leading to sales in kiosks, food stores and gas stations.59, 60 The deregulation was proceeded by a lively debate concentrating on for instance the role of NRT in SC.60 Currently, in Finland, NRT products are widely available, their pricing is free, and they are not included in the national reimbursement scheme. According to the results of the annual national survey on the health and health behaviour among the Finnish adult population, nearly 20% of Finnish smokers use NRT.61 NRT products are the third largest group of non‐prescription medicines when measured by their sales.62

STUMPPI national Internet‐based discussion forum for SC

The Organisation for Respiratory Health in Finland coordinates a long‐term national programme to reduce the consumption of tobacco products particularly among adults. Several other, non‐governmental health organizations take part in this programme. Since 2002, the organization has maintained a national tobacco cessation phone line, and since 2004, an Internet portal called STUMPPI, both financed by the Finland's Slot Machine Association (RAY) owned by the government.

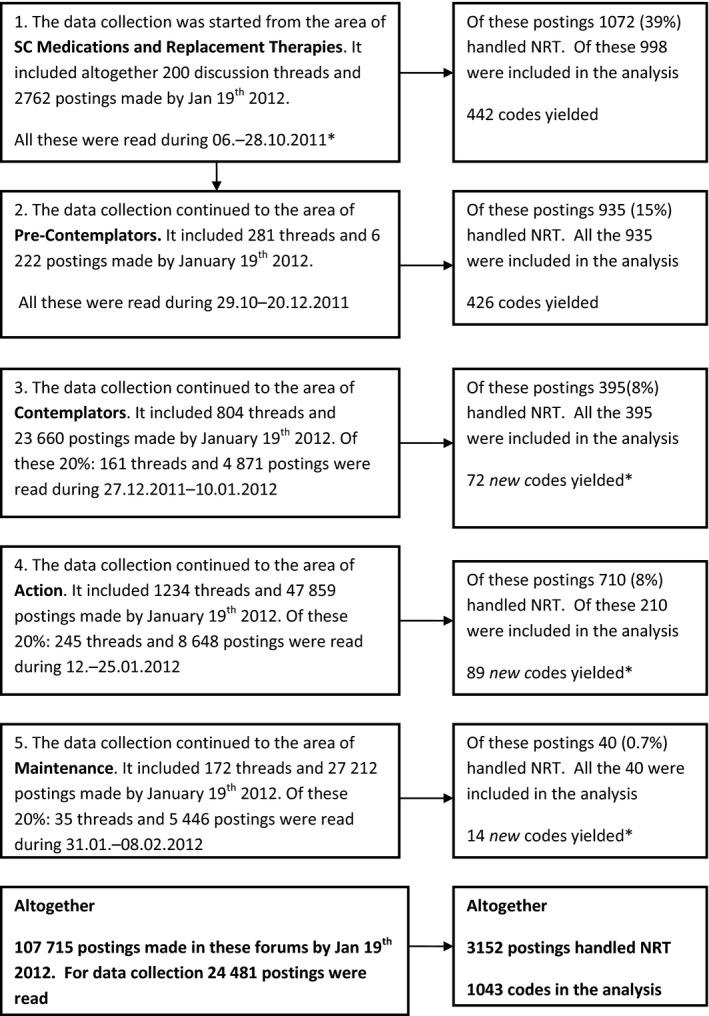

The STUMPPI website (2012) is constantly updated, and it contains a lot of current information on tobacco consumption and cessation.63 The website provides free services for registered and unregistered quitters and health professionals. The services includes an Internet‐based question and answer service, the possibility to speak with a health professional and ten Internet discussion areas, each with a different focus. The discussion areas have been part of the STUMPPI portal since January 2007. These discussion areas either target quitters at different stages of their SC process (Pre‐contemplators, Contemplators, Action, Maintenance), or they are related to specific topics (Joy of Success, SC Medications and Replacement Therapies, Cravings, Temptations and Ways to Deal with Them, Annoying Matters and Cessation from Snus) (Fig. 1). Health‐care professionals specialized in SC and working for STUMPPI, monitor the discussions for their appropriateness, but they do not intervene in the content of the discussions.

Figure 1.

Discussions in the areas of the STUMPPI forum and data collection.

Approximately 100 000 different users visit the STUMPPI discussion areas annually. By the end of May 2014, there were 5655 registered users in the forum. The users use the forum in very different ways: According to a rough estimation, about 40% of the registered users only read the threads and do not post themselves. A third of the registered users post less than five postings and a quarter posts over ten postings during their cessation process. However, there is a small group (approximately 5%) of very active users, who post sometimes over thousands of postings and stay on the forum for years.

Data collection and analysis

The five most popular discussion areas were selected for this study. The selected areas were those concentrating most clearly on the role of NRT in different stages of SC process. The data were collected during October 2011–March 2012. The following discussion areas were included: SC Medications and Replacement Therapies; Pre‐Contemplators; Contemplators; Action; and Maintenance. The data collection and analysis were started by reading systematically through all the postings made during January 2007 and January 2012 on the discussion areas of SC Medications and Replacement Therapies and Pre‐Contemplators (Fig. 1). The postings relevant to our research question were copied verbatim onto two specific MS Word files (Fig. 1).

The collected postings were analysed by applying the inductive content analysis method.64 This method pays special attention to the crucial aspects of the textual material, and it produces classifications based on the content of the material. The unit of analysis was fixed as one or more sentences dealing with opinions, perceptions, experiences or expectations related to NRT use or comparing NRT to other SC methods (prescription medicines or non‐pharmaceutical methods, including cold turkey).

The postings in the files were carefully read through several times to ensure comprehension of their fundamental features. Then, for each sentence, a short code, true to its original expression, was created by the comment action of MS Word. For each posting, only one code per viewpoint was created, but one posting could include several viewpoints and so yield several codes. The codes covering similar or nearly similar meanings were combined in a separate MS word file. These were grouped again to form categories, which were named according to their overall content.64 Later, the categories were again grouped to form broader categories, and finally, preliminary themes. The areas of SC Medications and Replacement Therapies and Pre‐Contemplators yielded altogether 868 codes (Fig. 1). On the basis of these codes, we created the first draft of our coding scheme. To gain an understanding of quitters’ perceptions of NRT at different stages of SC and assure data saturation, we extended the data collection to additionally include the following three discussion areas: Contemplators; Action (the most active forum); and Maintenance (Fig. 1). Due to the high number of postings on these areas, every fifth thread (20%) in sequence made between January 2007 and January 2012 was explored (Fig. 1). During the data collection from these areas, a log book in MS Excel was kept for each thread to count the number of the postings concerning NRT. Only postings introducing a new viewpoint compared to the original coding scheme were entered in to the analyses (Fig. 1). During the data collection, the initial coding scheme was modified: the main themes remained, but new categories emerged. Data saturation was reached in the Maintenance area after 8% of the threads were read.

After the initial data analysis, we ensured that no data from the discussions were missing from the analysis. For this purpose, all the MS Word files from different discussion areas (original data) were re‐read in March 2012. The original data were arranged according to the emerged themes in three new MS Word files. In the files, all sentences were arranged according to the order of categories. No data were left out of the coding scheme.

Ethical approval

Postings on the Internet can be seen as a public domain, which allows researchers to proceed without asking for informed consent from the participants.54 The University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board in Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences gave their approval for this study in June 2011. We also received permission and guidance from the Organisation for Respiratory Health in Finland to use STUMPPI forum for the data collection.

Results

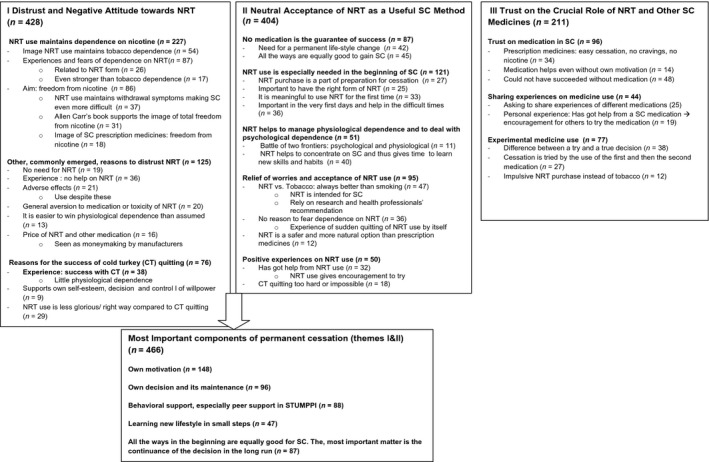

Three major themes emerged explaining how NRT is perceived as a SC method (conceptualized in Fig. 2). They were as follows: (i) distrust and negative attitude towards NRT; (ii) neutral acceptance of NRT as a useful SC method; and (iii) trust on the crucial role of NRT and other SC medicines. Most of the codes were related to the first (n = 428) and second theme (n = 404). The third theme was less common (n = 211). The next paragraphs will explain the themes in more detail.

Figure 2.

Key perceptions and experiences related to NRT as emerged from the discussions. The number of postings related to each category is reported in brackets.

Authentic examples of the postings are given in Table S1.

I Theme: Distrust and Negative Attitude towards NRT

Dependence on NRT as a key explanation

The most common explanation given by posters on the forum for their distrust of NRT was the fear that the use of NRT would maintain tobacco dependence or cause a new NRT dependence.

Nicotine was recognized as the substance responsible for the dependence on tobacco products. For this reason, some participants even considered NRT use as equal to smoking. Several participants reported their NRT dependence experiences. Some posters even stated that they had experienced a dependence on NRT that they felt was even stronger than their dependence on tobacco. They also said they had started to smoke again due to their NRT dependence.

Several participants highlighted that total freedom from nicotine was the ultimate goal of all SC attempts, and this freedom should be achieved as soon as possible. NRT use was often found to maintain withdrawal symptoms, and thus, make quitting even more difficult in the long run. Furthermore, in various postings, NRT use in quitting was found to be more harmful than beneficial. These attitudes reflected in the postings were partly due to the popularity of Allen Carr's book of Easyway ® to Stop Smoking (2012), which introduced the idea of total freedom from nicotine as the only real cessation.65 The pharmacological effects of NRT on receptors were seen in the postings as an explanation for NRT products’ addictive and withdrawal symptom maintaining characteristics. Withdrawal symptoms were seen as a sign of recovery after quitting NRT use.

Other common reasons for distrust

In addition to the fear of dependence on NRT, the use of these products was found to be unhelpful and unnecessary for several other reasons. Several participants told how they had experienced that no help was gained due to too low a dosage or minimal use. Some also reported failure despite adhering to the instructions for use. Also experiences or existing fear of adverse effects caused by NRT was brought up, although NRT use often continued despite these effects. A few participants considered that most quitters could do without nicotine, although the need for NRT has been misinterpreted, because of the overestimated physiological nicotine dependence. In some postings, the strong aversive attitude towards NRT use was also associated with the assumed toxic nature of NRT or general aversion to medications. In the discussions, the prices of NRT and prescription SC medications were mentioned as an obstacle to their use. Although the price of NRT was generally found reasonable compared to the price of tobacco.

Reasons for the success of cold turkey quitting

In several postings, distrust towards NRT was also explained by the success of quitting without using any pharmaceuticals. Even specific threads were dedicated to this so‐called cold turkey (CT) quitting. Reasons given for CT quitting were ease of quitting, absence of withdrawal symptoms indicating low nicotine dependence and freedom from nicotine. CT quitting was also connected with the idea of controlling one's own mind and life without the use of medicine. Some posters introduced CT quitting as a better option than NRT use in the quitting process. This culminated in the idea of NRT use as the less right way to quit, and thus, NRT users are not real quitters as long as they continue NRT use.

Usage patterns highlighted

In various postings, the negative perceptions towards NRT were reflected in the aim of not using NRT at all in SC. If this was the case, product use should be intentionally restricted to as short a time and as minimal a dosage as possible. The limited use was thought to be acceptable when it was a must, in the worst stages or during the first days of SC. Strict control of the use was perceived as a way to avoid the feared NRT dependence. However, it was also highlighted that the low dosage may have been the reason for their failure in previous quitting attempts.

II Theme: Neutral Acceptance of NRT as a Useful SC Method

Participants having a neutral attitude towards NRT use found it helpful. Though, it was highlighted that no medication guarantees successful quitting, and the actual work to maintain SC should be done by the quitters themselves. Similarly, it was highlighted that all the ways to quit smoking are equally good, and no‐one should judge the use of medication.

NRT use is especially needed in the beginning of SC

Several postings highlighted the importance of NRT use in the beginning of the cessation process. The purchase of NRT products before the actual quitting was an important preparatory step just like deciding the quitting date or subscribing to STUMPPI forum. The importance of finding the most suitable form of NRT was highlighted. A concrete obstacle mentioned was the limited NRT product assortment in most of the outlets outside of pharmacies. Several participants reported especially on their first time NRT use experiences, indicating it as being a meaningful and symbolic act. Various posters highlighted that NRT is needed especially in the very first days of the cessation and to deal with the most difficult situations, like strong cravings, withdrawal symptoms and the urge to smoke.

NRT use helps to manage physiological dependence and to deal with psychological dependence

In the discussions, a clear difference was made between physiological nicotine dependence and psychological dependence as components of tobacco dependence. In nearly all postings, psychological dependence was admitted to be the hardest part of SC. To concentrate on its management, one needed relief from physiological withdrawal symptoms, which NRT use could make tolerable. The concentration on psychological dependence included building up a new smoke‐free self‐image, learning a totally new lifestyle, daily habits and mentally making a permanent change.

Relief of worries and acceptance of NRT use

In the discussions, the most common justification for NRT use was the perception that NRT use is always a better option than continuing smoking. Furthermore, NRT usage was supported by the fact that NRT products are medicines intended for SC, and therefore, their use is highly recommended. Also, health professionals’ recommendations and research results were presented as a justification for NRT use, although these were not as such prominent justifications as participants’ personal experiences.

Several participants gave advice to others to relieve their fear of possible NRT dependence. They recommended concentrating first on mastering tobacco dependence. Later, there would be time to quit NRT use in small steps. Further, several quitters reported their own experience of how NRT use suddenly diminished by itself and considered NRT dependence rare. A few participants told how their own negative attitude towards NRT use had changed and how they had learned to accept NRT use. NRT was found to be a safer and more natural option compared to prescription medicines. It was also regarded as a safer option for those quitters who suffered from chronic conditions, like mental illness.

Positive experiences of NRT use

Several participants reported how they had gained help from NRT use. Furthermore, some participants, who self‐reported about their personal experience of a heavy tobacco dependency or long tobacco history, found NRT use encouraged them to at least to try to quit, which they otherwise would not have done. It was outlined that the majority of quitters do benefit from NRT use in SC, while CT quitting was regarded as too hard or even an impossible way.

Usage patterns highlighted

It was highlighted that it is important to use NRT for as long as the instructions for use recommend. Further, the use with sufficient dosage was highlighted including the benefits of combination therapy of patch and short‐acting NRT form. The sufficient treatment period and dosage were considered crucial in learning to cope with psychological dependence. However, some participants reported their own experience of how they were able to quit using NRT with a very low dosage and a short treatment period as they had learned to deal with the temptation to smoke or they experienced the given dosage to be too high. A detailed NRT treatment plan, which included an individualized and decreasing dosage regimen, was recommended to gain cessation. It was also seen to help in avoiding the feared NRT dependence.

Ways to maintain permanent cessation emerged from Themes I and II

Despite the positive and negative attitudes towards NRT use, discussion participants shared opinions on the most crucial components of permanent SC. These were the quitter's strong personal motivation, psychological change to manage his or her life, permanent decision not to smoke even a puff and the peer support provided by STUMPPI forum. The forum made it possible to gain and express support, share the best and worst moments of the quitting process or ask others about the most acute questions. This psychological peer support outnumbered the importance of any pharmacotherapy. Further, it was highlighted that in the long run, all the ways to support quitting are equally good, but most important is how to maintain a permanent lifestyle change.

III Theme: Trust on the crucial role of NRT and other SC medicines

Trust on medication in SC

Although the idea of medication use to achieve cessation was mainly balanced, some postings highlighted the crucial role of medication in SC. These perceptions were especially associated with prescription medicines (bupropion and varenicline) although trust on NRT was expressed, but less frequently. Prescription medicines were associated with the image of easy cessation, which was explained by their mechanism of action, course of treatment and the absence of nicotine. The culmination on the trust on medication was found among participants who posted that medicines guarantee cessation without their own true quitting motivation, or the success of their quitting was highly dependent on the medication.

Sharing experiences on medicine use

Especially under the discussion area on SC Medications and Replacement Therapy, various threads concentrated on sharing experiences of different medications. Medicines’ characteristics were compared such as efficacy, adverse effects and price. Medicine users having strong trust in their medication actively recommended the treatment option to other participants. Despite this, the individuality of the SC process and suitability of different SC aids as a personal choice were mostly highlighted.

Experimental medicine use

Medicine use in quitting was also reported to be experimental and the difference between true decision and medication use attempts was established. Some participants reported on how their previous quitting attempts had failed due to a lack of motivation. Despite this, they continued to experiment with other medicine use, in hope of achieving cessation. An example of this was an impulsive NRT purchase instead of tobacco without actually considering cessation.

Discussion

This qualitative analysis of 3152 postings in STUMPPI forum revealed a variety of forum participants’ perceptions in valuing NRT use in SC. Of these, the most common one was a negative attitude towards NRT use (Theme 1), offset by an acceptance of NRT use early on as a necessary aid in SC attempts (Theme II). However, the most highlighted component of successful quitting was the quitters’ psychological empowerment, which included their own decision and motivation to maintain a new smoke‐free lifestyle. This indicates that most of the participants had low or balanced expectations towards the role of NRT in SC. A great variety of NRT usage patterns emerged, with the emphasis on avoiding NRT use or at least minimizing the dose and treatment period (Tables 1 and S1). All these findings are in line with the usage patterns previously reported in the literature, although our study provided some new insights into some of the usage patterns (Table 1).

As the role of NRT is widely acknowledged in the treatment of physiological tobacco dependence, it was surprising that so many STUMPPI discussion forum participants had a negative attitude or experiences towards NRT use. The data for this study covered a period of 5 years (2007–2012), which is the immediate period after the deregulation of NRT product sales in the open market in Finland.59, 60 The deregulation led to the nearly exponential increase in NRT sales, but shifted the sales towards the smallest pack sizes of the mildest NRT gum products.62 This may have influenced the perceived effectiveness of NRT in SC. Recent evidence from the USA and Great Britain indicates that even though NRT use has significantly increased, smoking has not correspondingly decreased.66, 67 In further studies, it might also be interesting to assess the influence of increased NRT sales on smoking prevalence in Finland. These findings question the value of NRT in SC without a treatment plan and behavioural support.

Our findings confirm the previous findings that fears and experiences of NRT dependence are common among smokers and quitters. Actually, these fears and experiences were the key explanations for the negative attitude towards NRT use in our study. Smokers and quitters fear dependence on NRT, perceive NRT use only as a change of nicotine delivery from tobacco to NRT and maintenance of their nicotine dependence (Table 1). Although population‐based studies suggest that NRT dependence is rare,36, 37 many smokers and quitters fear dependence on NRT, and this hinders its appropriate use. Health professionals should take these smokers’ perceptions seriously and find new innovative and customized ways of being involved in the SC process in partnership with smokers. Similarly, the Finnish Current Care Guideline highlights the health professionals’ active role in SC to support quitters’ empowerment and counsel the rational use of pharmaceutical aids.58 NRT use can be a part of an individualized SC plan, but it cannot solely rely on it. The SC plan should take advantage of the smoker's own willingness to quit and make lifestyle changes. It should also respect non‐medical methods to support SC. In addition, health‐care professionals should be better aware of the group of NRT users who have become addicted to these products and need help in a planned withdrawal.

The discussion participants found the social support and possibility to reflect on one's SC process in the STUMPPI discussion community crucial for SC. Similarly, previous evidence suggests that Internet‐communities support better self‐efficiency, empowerment and health outcomes.48, 50 Peer support provided in the forums should be far better utilized to provide innovative, new SC services, based on quitters’ preferences. Similarly, the strategy of the Canadian and American leading National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative highlights the importance of assessing and understanding individual smokers’ needs, expectations and desires instead of considering them as passive treatment users.68 As quitters make the last choice whether to use or not to use specific SC methods, their perspectives should be a key priority in developing effective SC support, instead of the priorities of health professionals or manufacturers of SC interventions. Peer support‐based e‐services could be provided at a very low cost to the society and the individual user compared to traditional methods, such as pharmacotherapy. The decision makers coordinating SC services should understand the value of social support to their users, and more services utilizing peer support should be offered as one additional component of SC.

Most of the discussion participants were very knowledgeable on smoking, SC and methods supporting SC. Contrary to common concerns about the quality of health‐related information in the Internet discussions, there is evidence that participants critically evaluate the information provided in the discussions and individually have their own opinions and make up their own treatment plans.50 More research from the smokers’ and quitters’ perspective is needed to assess the real value of NRT compared to other methods in SC.

Our qualitative study applied the evaluation criteria of rigour of qualitative analysis69, which was modified suitably for Internet‐based research.49, 69 In terms of conformability, we had to balance between estimating theoretical saturation by researchers’ real‐time participation64 and appreciation of the natural occurrence of postings.49, 64 We analysed only five discussion areas because most of the postings in STUMPPI forum were made in these five areas. We systematically analysed these discussion areas and continued data collection until no new viewpoints emerged (see Methods). By doing this, we gained a rich and full overview of different aspects. In terms of the dependability of our findings, the results were discussed with professionals in the STUMPPI organization who daily follow the virtual discussions.

This analysis of 3152 postings during a 5‐year period (2007–2012) was selected for our study, to provide longitudinal data and an understanding of smokers’ perceptions on SC. This unique material provided insights into smokers’ and quitters’ thoughts and behaviours without the interference of a researcher. On the other hand, Internet discussion‐based data must be interpreted cautiously.49, 54, 70 The analysis of Internet discussions is based on what the participants on the forums ‘said’, rather than on their interpretation of what happened. The investigator must rely on postings without verifying these interpretations, that is by further questions, as could be done in an interview setting.54 Furthermore, there is evidence that proactive postings in the threads may receive the greatest diversity of responses, which can highlight the most critical viewpoints.70 Further, due to the anonymity in the discussions forums, it is possible to express fabricated comments. One could expect that largely too positive comments on any medicine use could be motivated by financial interests. However, while reading through the discussion chains, we noticed that the most positive or highly critical comments were balanced out by other discussion participants and as such the discussion chains presented mostly balanced opinions. Further, the vast material assessed offered us a great variety of aspects of NRT use, which was matched with different viewpoints. On the other hand, one could expect that smokers and quitters, who have a positive attitude towards NRT use, would not go to the STUMPPI forum. Furthermore, the study was not able to collect data on the perceptions of NRT users, who do not use the Internet. However, as our findings on NRT usage patterns were in line with the ones previously reported in the literature (Table 1), we expect our findings to give reliable insights into the smokers’ and quitters’ perceptions. In accordance with previous findings on sensitive health issues54, our experience found Internet discussion forum‐based data to be more informative and suitable for establishing smokers’ and quitters’ perspectives rather than traditional qualitative interviews. The discussion forums are proven to be a suitable source for information on users’ experiences on medications.71 In future, these forums should be more utilized in the research on medication use behaviours.

Conclusions

The majority of STUMPPI forum participants had low or balanced expectations towards the role of NRT in SC. From the smokers’ and quitters’ perspective, the most highlighted component of successful quitting was the quitters’ psychological empowerment, which included their own decision and motivation to maintain a new smoke‐free lifestyle. This study revealed that in the discussions, several smokers and quitters had different kinds of perceptions of NRT use. Of these perceptions, the fear of dependence on NRT products was very commonly brought up in the discussions. Health professionals should be aware of these smokers’ perceptions on NRT and find new innovative and customized ways of being involved in the SC process in partnership with smokers and quitters. Further, more research from the smokers’ and quitters’ perspective is needed to assess the real value of NRT compared to other methods in SC.

This experience of utilizing Internet discussion forums in data collection supports the previous findings to use these forums in data collection for information on medicine users’ experiences on medications. The trustworthiness of Internet discussion‐based data must be carefully assessed from several perspectives as they are different to traditional interview‐based studies. Nevertheless, these forums should be more utilized in researching medication use behaviours.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from Finnish Cultural Foundation (grant number 0007084/2007) and the Association of Finnish Pharmacies.

Supporting information

Table S1. The Key themes related to attitudes, experiences and expectations to NRT with reflections to usage patterns and examples of original citations.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the Organisation for Respiratory Health in Finland and especially Organisation Manager Mervi Puolanne for the possibility to use STUMPPI forum for data collection. We are grateful for smoking cessation specialist Taina Kangas from STUMPPI Organisation for her excellent comments related to the data analysis. We are grateful to Richard Stevenson M.Sc. for linguistic help with the manuscript.

References

- 1. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Brief Interventions and Referral for Smoking Cessation. Public Health Intervention Guidance no.1 (PH1). Manchester: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB et al Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: US Dept. of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Batra A. Treatment of tobacco dependence. Deutsches Ärztblatt International, 2011; 108: 555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zwar N, Richmond R, Borland R et al Supporting Smoking Cessation: A Guide for Health Professionals. Melbourne, Vic.: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gross B, Brose L, Schumann A et al Reasons for not using smoking cessation aids. BMC Public Health, 2008; 8: 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chapman S, MacKenzie R. The global research neglect of unassisted smoking cessation: causes and consequences. PLoS Medicine, 2010; 7: e1000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yeomans K, Payne KA, Marton JP et al Smoking, smoking cessation and relapse patterns: a web‐based survey of current and former smokers in the US. The International Journal of Clinical Practice, 2011; 65: 1043–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hung WT, Dunlop SM, Perez D, Cotter T. Use and perceived helpfulness of smoking cessation methods. Results from a population survey of recent quitters. BMC Public Health, 2011; 11: 592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shiffman S, Sweeney CT. Ten years after the Rx‐to‐OTC switch of nicotine replacement therapy: what have we learned about the benefits and risks of non‐prescription availability? Health Policy, 2008; 86: 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheong Y, Young HH, Borland R. A comparison between abrupt and gradual methods using data from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Study Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2007; 9: 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Medbo A, Meibye H, Rudebeck CE. “I did not intend to stop. I just could not stand cigarettes any more” A qualitative interview study on smoking cessation among the elderly. BMC Family Practice, 2011; 12: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cook‐Shimanek M, Burns EK, Levinson AH. Medicinal nicotine nonuse: smokers’ rationales for past behavior and intentions to try medicinal nicotine in a future quit attempt. Nicotine Tobacco Research, 2013; 15: 1926–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hammond D, McDonald PW, Fong GT, Borland R. Do smokers know how to quit? Knowledge and perceived effectiveness of cessation assistance as predictors of cessation behavior Addiction, 2004; 99: 1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaper J, Wagena EJ, Willemsen MC, Van Schayck CP. Reimbursement for smoking cessation treatment may double the abstinence rate: results of a randomized trial. Addiction, 2005; 100: 1012–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughes JR, Marcy TW, Naud S. Interest in treatments to stop smoking. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009; 36: 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bansal MA, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Giovino G. Stop‐ smoking medications: who uses them, who misuses them, and who is misinformed about them. Nicotine Tobacco Research, 2004; 6: S303–S310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferguson SG, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S, Sembower MA, Rohay JM, Allen J. Providing accurate safety information may increase a smoker's willingness to use nicotine replacement therapy as part of quit attempt. Addictive Behaviors, 2011; 36: 713–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vogt F, Hall S, Marteu T. Understanding why smokers do not want to use nicotine dependence medications to stop smoking: qualitative and quantitative studies. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2008; 10: 1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Etter JF, Perneger TV. Attitudes toward nicotine replacement therapy in smokers and ex‐smokers in the general public. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2001; 69: 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Rijt GAJ, Westernik H. Social and cognitive factors contributing to the intention to undergo a smoking cessation treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 2004; 29: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mills EJ, Wu P, Lockhart I, Wilson K, Ebbert JO. Adverse events associated with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for smoking cessation. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of one hundred and twenty studies involving 177 390 individuals. Tobacco Induces Diseases, 2010; 8: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McNeill A, Foulds J, Bates C. Regulation of nicotine replacement therapies (NRT): a critique of current practice. Addiction, 2001; 96: 1757–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fiore MC, Baker TB. Clinical practice. Treating smokers in the health care setting. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2011; 365: 1222–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mooney ME, Leventhal AM, Hatsukami DK. Attitudes and knowledge about nicotine and nicotine replacement therapy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2006; 8: 435–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Walker N, Howe C, Bullen C et al Does improved access and greater choice of nicotine replacement therapy affect smoking cessation success? Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 2011; 106: 1176–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walsh RA. Over‐the‐counter nicotine replacement therapy: a methodological review of the evidence supporting its effectiveness. Drug & Alcohol Review, 2008; 27: 529–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shaw JP, Ferry DG, Pethica D, Brenner D, Tucker IG. Usage patterns of transdermal nicotine when purchased as a non‐prescription medicine from pharmacies. Tobacco Control, 1998; 7: 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sims TH, Fiore MC. Pharmacotherapy for treating tobacco dependence. What is the ideal duration of therapy? Drugs, 2002; 16: 653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paul CL, Walsh RA, Girgis A. replacement therapy products over the counter: real‐life use in Australian community. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 2003; 27: 491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gilpin EA, Messer K, Pierce JP. Population effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids for smoking cessation: what is associated with increased success? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2006; 8: 661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burns EK, Levinson AH. Discontinuation of nicotine replacement therapy among smoking‐cessation attempters. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2008; 34: 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Balmford J, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings KM. Adherence to and reasons for premature discontinuation from stop‐smoking medications: data from the ITC Four‐Country Survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2011; 13: 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shiffman S, Sweeney CT, Ferguson SG, Sembower MA, Gitchell JG. Relationship between adherence to daily nicotine patch use and treatment efficacy: a secondary analysis of 10‐week randomized double blind placebo‐controlled clinical trial stimulating over the counter us in adult smokers. Clinical Therapeutics, 2008; 30: 1582–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ebbert JO, Hayes JT, Hurt RD. Combination pharmacotherapy for stopping smoking . Drugs, 2010; 70: 643–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Food and Drug Administration . Transcript of the Non‐Prescription Drugs Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hughes JR, Pillitteri JL, Callas PW, Callahan R, Kenny M. Misuse of and dependence on over‐the‐counter nicotine gum in a volunteer sample. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2004; 6: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hughes JR, Adams EH, Franzon MA, Maquire MK, Guary J. A prospective study of off‐label use of, abuse of, and dependence on nicotine inhaler. Tobacco Control, 2005; 14: 49–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beard E, McNeill A, Aveyard P, Fidler J, Michie S, West R. Use of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking reduction and during enforced temporary abstinence: a national survey of English smokers. Addiction, 2010; 106: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. West R, Hajek P, Foulds J, Nilsson F, May S, Meadows A. A comparison of the abuse liability and dependence potential of nicotine patch, gum, spray and inhaler. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2000; 149: 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Etter JF. Addiction to the nicotine gum in never smokers. BMC Public Health, 2007; 7: 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hajek P, McRobbie H, Gillison F. Dependence potential of nicotine replacement treatments: effects of product type, patient characteristics and cost to user. Preventive Medicine, 2007; 44: 230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Etter JF, Stapleton JA. Nicotine replacement therapy for long‐term smoking cessation: a meta‐analysis. Tobacco Control, 2006; 15: 280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Etter JF. Dependence on nicotine gum. Poster presentation held in the 9th Annual Conference of the SRNT Europe: Madrid, 2007.

- 44. Gerlach KK, Rohay JM, Gitchell JG, Shiffman S. Use of nicotine replacement therapy among never smokers in the 1999‐2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2008; 98: 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marques‐Vidal P, Melich‐Cerveira J, Paccaud FA, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Cornuz J. High expectation in non‐evidence‐based smoking cessation interventions among smokers—The Colaus study. Preventive Medicine, 2011; 52: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Burri M, Baujard V, Etter JF. A qualitative analysis of an Internet discussion forum for recent ex‐smokers. Nicotine Tobacco Research, 2006; 8: S13–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Selby P, van Mierlo T, Voci SC, Parent D, Cunningham JA. Online social and professional support for smokers trying to quit: an exploration of first time posts from 2562 members. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2010; 12: e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. LaCourisiere SP, Knobf T, McCorkie R. Cancer patients’ self‐reported attitudes about the Internet. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 2005; 7: e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Im EO, Chee W. An online forum as a qualitative research method. Nursing Research, 2006; 55: 267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Armstrong N, Powell J. Patient perspectives on health advice posted on Internet discussion boards: a Qualitative study. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coulson NS, Buchanan H, Aubeeluck A. Social support in cyberspace: a content analysis of communication within a Huntington's disease online support group. Patient Education & Counseling, 2007; 68: 173–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Van Uden‐Kraan CF, Drossaert CC, Taal E, Seydel ER, van de Laar MAFJ. Participation in online patient support groups endorses patients’ empowerment. Patient Education and Counseling, 2009; 74: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pohjanoksa‐Mäntylä M. Medicines Information Sources and Services for consumers: A special focus on the internet and people with depression. Academic Dissertation. Division of Social Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Helsinki,2010.

- 54. Seale C, Charteris‐Black J, MacFarlane A. Interviews and internet forums: a comparison of two sources of qualitative data. Qualitative Health Research, 2010; 20: 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database for Systematic Reviews, 2008; 1: CD000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kurko T, Salimäki J, Airaksinen M, Silén S, Pietilä K. The development and importance of Finnish community pharmacies’ involvement in smoking cessation in 1985‐2011. Dosis, 2011; 27: 140–152. [in Finnish with English abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Association of Finnish Pharmacies . Action plan community pharmacies supporting smoking cessation. Available at: http://www.savutonkunta.fi/sites/default/files/docs/apteekit_tupakasta_vieroituksen_tukena_toimenpideohjelma.pdf, accessed 27 July 2014 [in Finnish].

- 58. Working group set up by the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim and the Finnish Association for General Practice. Tobacco Dependence and Cessation, Current Care Guideline 2002, updated version, 2012. [in Finnish with English abstract].

- 59. Medicines Act and Decree and Amendments (395/1987), 1987. Available at: http://www.fimea.fi/download/18580_Laakelaki_englanniksi_paivitetty_5_2011.pdf, accessed 3 January 2014.

- 60. Kurko T, Silvast A, Wahlroos H, Pietilä K, Airaksinen M. Is Pharmaceutical policy evidence‐informed? A case of the deregulation process of nicotine replacement therapy products in Finland. Health Policy, 2012; 105: 246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Helldán A, Helakorpi S, Virtanen S, Uutela A. Health Behavior and Health Among the Finnish Adult Population, Spring 2013. National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2013. Available at: http://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/110841/URN_ISBN_978-952-302-051-1.pdf?sequence=1, accepted 31 May 2014 [in Finnish with English abstract].

- 62. Finnish Medicines Agency Fimea, Social Insurance Institution . Finnish Statistics on Medicines, 2010. Helsinki: Edita Prima Oy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63. STUMPPI (2012). Description of the actions. Available at: http://www.hengitysliitto.fi/Savuttomuus/Stumppi/, accessed 3 January 2014 [In Finnish].

- 64. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2008; 62: 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Carr A. (2012) Easyway to stop smoking. Available at: http://www.allencarrseasyway.com, accessed 3 January 2014.

- 66. Pierce JP, Sharon E, Cummins MM, White AH, Messer K. Quitlines and nicotine replacement for smoking cessation: do we need to change policy? Annual Review of Public Health, 2012; 33: 341–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kotz D, Brown J, West R. ‘Real‐world’ effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments: a population study. Addiction, 2014; 109: 491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Backinger CL, Thomton‐Bullock A, Miner C et al Building consumer demand for tobacco‐cessation products and services: the national tobacco cessation collaboratives consumer demand roundtable. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2010; 38: S307–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lincoln YS, Cuba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rollman JB, Krug K, Parente F. The Chat Room Phenomenon: reciprocal Communication in Cyberspace. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 2000; 3: 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schröder S, Zöllner YF, Schaefer M. Drug related problems with Antiparkinsonian agents: consumer Internet reports versus published data. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 2007; 16: 1161–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. The Key themes related to attitudes, experiences and expectations to NRT with reflections to usage patterns and examples of original citations.