Abstract

Background

User involvement in long‐term care has become official policy in many countries. Procedural and managerial approaches to user involvement have numerous shortcomings in long‐term care. What is needed is a different approach that is beneficial and tuned to the needs of clients and professionals.

Aim

This article presents a care‐ethics approach to involvement. We illustrate this approach and its practical implementation by examining a case example of user involvement in long‐term elderly care.

Methodology

This case example is based on an action research project in a residential care home in the Netherlands. Seven female clients participated in the process, as well as diverse groups of professionals from this residential care home.

Results

The clients were concerned about meals, and collectively they became empowered and came up with ideas for improving meals. Professionals also shared the clients' experiences with meals, first in homogeneous groups and then in heterogeneous meetings with the client group. This process led to the development of partnership relations between clients and professionals.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a care‐ethics approach to user involvement is a means to increase resident empowerment in long‐term care. Clients and professionals start sharing their experiences and values through dialogue, and they develop mutual trust and openness while doing so.

Keywords: care‐ethics, collective action, empowerment, long‐term care, older people, partnership

Introduction

Long‐term care refers to care for older people, chronic patients and people with disabilities lasting more than 2 years. The expectation is that a considerable increase in the need for long‐term care will, in the near future, lead to more costs and a shortage of personnel. Failures to provide respectful, responsive and effective long‐term care have recently led to heated public debate about cost and quality in many European countries.1 The general belief is that institutional arrangements for long‐term care have led to the overprofessionalization of care, and that clients are approached as the passive receivers of that care. Policy resolutions prioritize community‐based care, individual choice and involvement in decision‐making and governance processes. It is assumed that people who need care have the right, and sometimes even an obligation, to influence the provision of those services.

Involvement in welfare and care institutions in the Netherlands is legally regulated through the Participation (Clients of Care Institutions) Act (Wmcz). Rights and procedures are clearly defined, but in practice tension arises between management and client councils leading to tokenism and a lack of influence.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Client councils are believed to have a voice, but in reality they mainly respond to policy documents and strategic decisions that have already been taken. The issues that are really important for clients, often involving day‐to‐day practicalities and well‐being, are expressed as individual complaints, and not pooled and placed on the policy agenda at a higher level. Another problem involves the issue of representation.7, 8 Councils work with representatives, often family members, who find it hard to stay in touch with clients. This leads to a situation in which councils have problems representing the majority, and the ever‐changing values and interests of an increasingly diverse group of patients.

In addition to a procedural approach, managerial responses to client involvement have led to the introduction of consumer indexes and other (digital) questionnaires to measure consumer satisfaction.9 These methods, which, in reality, involve nothing more than box ticking, are often one‐sidedly informed by management information needs, leaving little room for clients to be more structurally involved and voice their concerns.10 As clients can only express their satisfaction or dissatisfaction, they have no influence at all on any decisions surrounding care improvements.

A problem in both the procedural and managerial approaches to user involvement is the underlying myth of the autonomous subject in control and exerting choice. This myth does not gel with the reality of the people who lack the ability to influence the direction of their lives without support.11, 12 Such normative ideals and obligations of involvement may even have the opposite effect among people in vulnerable situations as it reinforces their incompetence.13 Barnes identifies another side‐effect of the consumer ideology: tension in the caring relationship with workers if clients start to act as consumers or users of care.2 This is indeed troublesome; care workers are the natural partners of clients, and the caring relationship is of the utmost importance for the well‐being of both clients and workers.

So, we see that both procedural and managerial approaches to involvement have their shortcomings. As user involvement is now the official policy of many health‐care bodies, there is an urgent need to develop a different approach, that is, an approach that benefits and is tuned to the needs of both clients and professionals.

The purpose of this article is to present a care‐ethics approach to involvement. We illustrate this approach by discussing a case study of user involvement in long‐term elderly care. Table 1 gives an overview of the differences between our approach compared with procedural and managerial approaches to involvement.

Table 1.

Three approaches to user involvement in long‐term care

| Procedural | Managerial | Care ethical | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aim | Establishing rights | Consumer satisfaction | Relational empowerment |

| Client councils | Measurements | Collective action | |

| Level of involvement | Advice | Information‐exchange | Partnership |

| Representative | Box ticking | Deliberative | |

| Responsibilities | Handed over to representatives | Individual | Collective |

Core aspects of a care‐ethics approach to involvement

Care‐ethics provides a new theoretical framework to conceptualize user involvement in long‐term care. Care‐ethics assumes that care is a fundamental human need and activity essential to well‐being and human flourishing.13, 14, 15, 16 Care‐ethics starts from a relational view on human beings. To put it simply: people need one another. In the context of involvement, this implies that the wish to become involved is motivated as much by the social need for connection as by the issue itself.2 Clients do not just want to influence their own life and environment, and they also look for meaningful contact and relationships. Moreover, influence can only be accomplished through relationships and mutual support. Care‐ethics helps us find ways to support the need for connectedness and dialogue, both among clients and between clients and care workers. Involvement is therefore viewed as a relational process.17, 18

A relational approach requires taking account of client dependency and of power differentials among clients and workers in residential settings. A collective process of involvement must therefore start among clients in the safe context of mutual encouragement.19, 20 We define collective action among clients as the joint and coordinated action of people based on their own agenda.21 This agenda covers topics that are important for people, and both stem from and generate solidarity within the wider community. In the context of care, this means that clients engaged in collective action do not act as consumers striving to protect their self‐interests, but rather as citizens working for a shared good.22 Through storytelling, clients develop their own agenda related to notions of well‐being and the good life.23, 24 This storytelling is essential for identifying dissatisfaction, whether material or immaterial, and for discovering a longed‐for‐future.25 Narration is also important to meaningfully and purposefully bring people together, to create events and to credit those who initiate action. Collective action is reinforced by collective experiences and the bond people develop in taking action.21

The kind of involvement we propose resonates with direct, deliberative forms of democracy.26 Deliberative democracy is not based on voting or the election of representatives. It is a form of democracy in which citizens debate directly with each other without the mediation of elected representatives.7 It is assumed that the experiential knowledge of lay persons is necessary in addition to technical or expert knowledge to arrive at solutions that acknowledge context, value and meaning.27 Ideally, deliberation leads to the transformation of perspectives, and consideration of various positions reaching beyond mere self‐interest.28, 29 For a fair deliberation, we need to consider power differentials between lay persons and experts. It has been demonstrated that if deliberation is to be fair, it is not enough to pay attention to the composition and selection of participants, the structuring of the agenda, framing of issues and goals. Simply including minor voices does not lead to equality. Emotive, rhetoric and anecdotic styles of speech may easily be discounted.30, 31, 32 Professionals' preparedness to listen and acknowledge emotional expressions are vital for fostering careful deliberation.

Involvement and deliberation are important values in themselves, but only become meaningful and relevant when they lead to transformative actions. Better care requires partnership between clients and workers. This collaboration entails openness, mutual respect for both expert and experiential knowledge, and above all trust.13, 33

Partnership implies a changing relationship, from a hierarchic power relation to a more equal relationship. This should not be envisaged as the handing of power from one person/group to another person/group or as a matter of taking power. Alternatively, we propose to understand this redressing of power as a process of empowerment for both clients and professionals. Relational empowerment sees empowerment as a mutually supportive process that mobilizes the strengths of people and communities.34, 35 Relational empowerment means that power emerges through interaction with others. One is never just someone who has power or is in need of empowerment. Everyone involved, regardless of power position and privileges, is both an agent and a subject in the empowerment process.36 This means that collaboration among clients may lead to the development of a collective interest and power and that their collaboration with other groups may lead to empowerment for all when they develop new partnerships.37

Based on this care‐ethics approach, we conducted several action research projects in residential care settings for older people.4, 5, 21 This resulted in the way of working that is discussed later.

A care‐ethics approach to involvement in practice

The care‐ethics approach proposed stimulates collective action by the formation of a client group and mobilizes the sources of strength within the group. The group dedicates itself to a particular topic that has come to the fore through their interaction and starts to share stories about that topic. The group process is fostered by a facilitator, either a professional, without a hierarchical relationship with clients, and/or a client council member or volunteer.

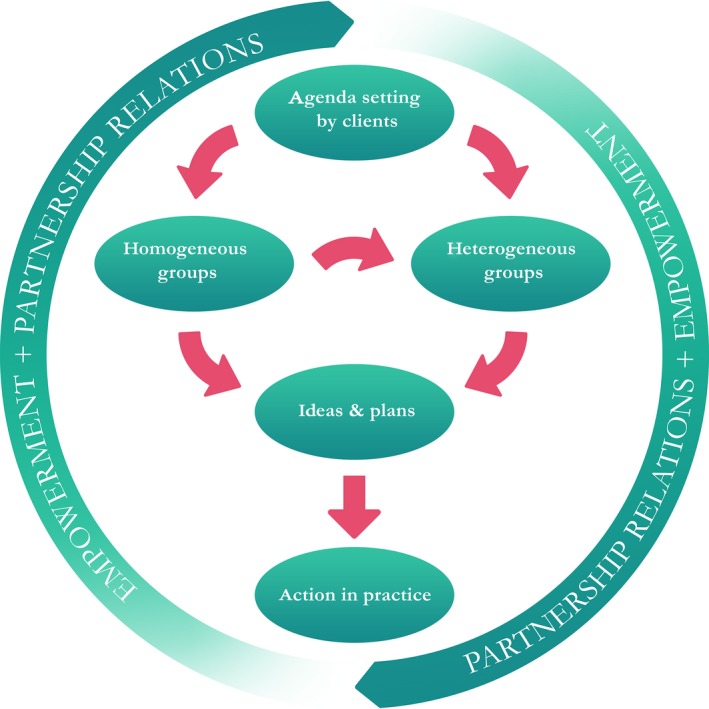

The process covers five steps in an action cycle (see Fig. 1):

Figure 1.

The action cycle and steps.

Agenda setting by clients: The facilitator brings together a group of eight to ten clients with diverse backgrounds, interests and experiences and organizes a meaningful exchange. Values, identity and life‐world experiences are shared through storytelling and an agenda for improving the quality of life and well‐being of clients is formulated.

Homogeneous groups: The client group (now an action group) is brought together on a regular basis by the facilitator (eight to ten times in total) to talk about a particular topic of interest. In this setting, they learn about each other's perspectives and to voice their own concerns. Creativity spurs on their conversation and helps them think in terms of possibilities rather than of problems. At the same time, the facilitator organizes homogeneous meetings with other stakeholders who are concerned with the topic to be addressed (at least one meeting per stakeholder group). These may be health‐care workers, volunteers, family, managers or other groups, depending on the issue. The idea behind these meetings is to ensure that other perspectives and views on the topic are raised.

Formulating ideas and plans: The action group and other groups formulate their ideas and plans for practice improvements. In this way, as many action agendas emerge as there are stakeholders. However, as a result of the deliberative process in which other stakeholders have already been introduced to the client perspective and vice versa, some ideas will overlap. The facilitator's role is to systematically structure all the ideas and plans with a view to finding common ground.

Heterogeneous groups: During the heterogeneous group meeting, clients and other stakeholders meet face‐to‐face to exchange ideas for practice improvements. There is a proportional balance between the number of clients and other groups to balance out the dialogue. The facilitator steers the dialogue and makes sure that clients feel their views are heard. When participants have developed mutual understanding, the facilitator put forward the various ideas and plans. Clients and stakeholders then talk about the workableness of combining and implementing ideas. This leads to a joint agenda for practice improvements.

Action in practice: Participants in the heterogeneous group sessions arrive at agreements about collaborative actions, which, after some time, will be jointly evaluated by the clients and stakeholders. New ideas for practice improvements may emerge from this collaboration.

Throughout the process, the facilitator plays an important role in supporting mutual understanding. Trust is created if the facilitator constructively deals with the power dynamics and distrust between stakeholders and prevents subtle forms of exclusion occurring.

The care‐ethics approach to involvement in action

We now illustrate the care‐ethics approach by discussing a case example of a project in which these principles were applied. The aim of this project was to involve older people in a residential setting in decision‐making processes concerning their life and well‐being. The researcher (VB) took on a proactive and facilitating role in the project, supervised by the first author. The project was run in a small residential care home in the south of the Netherlands. This residential care home had 129 apartments for people who could still live independently but who were in need of some kind of support due to frailty. A distinction is made between sheltered accommodation (56 apartments) and residential care apartments (73 apartments). The project covered a 1‐year period (2008–2009). Both top and middle managers were open to our approach and welcomed the project.

The first step was to bring together a group of residents to set their agenda. The staff were asked to recommend residents who were already involved in activities and residents who were less active. After a series of conversations, a core action group of seven women aged 82–92 decided to work on improving meals. All had some degree of physical infirmity and suffered from illness such as diabetes and/or rheumatism; and/or they had poor vision, hearing problems and decreased mobility.

Then, as part of the second step of the process, eight homogeneous (converging interests) meetings were held with this action group over a 7‐month period. The facilitator encouraged the group to explore the problems they had identified, which mainly involved meals, and included such aspects as atmosphere, nutrition, taste, variety, preparation, outsourced kitchen etcetera. In later gatherings, the group was encouraged to look for solutions. It was at this stage in the process that the participants began to feel they were one cohesive group, and they came up with a name for themselves: the Taste Buddies. A meeting was set up for the entire resident community to establish whether the other residents shared the same concerns. The facilitator also organized homogeneous meetings with kitchen staff and with the restaurant staff who served the meals.

As part of the third step of the process, two heterogeneous (diverging interests) dialogue meetings were held. First the action group met with the team leader and local manager to discuss their experiences with the meals and to explore where there might be room for improvement. Later, the Taste Buddies met with team leaders, kitchen staff, cook, restaurant staff, the local manager and a resident council member to discuss their ideas for improvement.

The fourth step in the process involves making plans. The Taste Buddies used a collage – illustrating their dream – to present their plans for improvement. Step five involves action in practice. The Taste Buddies were present during the job interviews to find two new cooks. The kitchen was reopened, and the meals cooked fresh on site. The Taste Buddies decided to continue as a group. Although two ladies passed away, new residents joined the group and the Taste Buddies still hold regular meetings with the cooks, kitchen staff and volunteers, where they discuss the menus and other relevant issues.

Role of the researcher – facilitator

As usual in action research, the researcher (VB) collected and analysed the data in collaboration with the participants in the project. See Table 2 for details. The meetings and interviews were carried out by the second author, and after consent audio recorded. The interviews were guided by a topic list. See Table 3 for the interview topics and observation items. The interviews took place in the apartment of the clients or work office and lasted about one and a half hour. Individual interviewees were handed a report of their interview for a member check. The second author kept field notes of the action group meetings as well as of the meetings with other stakeholders (kitchen staff, restaurant staff, client council, heterogeneous group) and reported them, together with a verbal explanation, to the participants at the next meeting. This integrates action and learning in an iterative process. At the same time, both researchers reflected on the data, with a focus on the dynamic, relational process of involvement and empowerment.

Table 2.

Data collection action research

| Data collection action research | Collaborative actions | |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews initializing phase |

|

|

| Homogeneous meetings |

|

|

| Heterogeneous meetings |

|

|

| Interviews evaluation phase |

|

|

Table 3.

Interview topics and observation items

| Interviews initializing phase |

Experiences with living/working in the residential care home Experiences with and perspectives on user involvement in this residential care home Communication and interaction among residents and between residents and professionals |

| Interviews evaluation phase |

Experiences with and insights on the user involvement in this project (barriers and success factors) Perspectives on possibilities for anchoring user involvement in the residential care home |

| Observation items (during homogeneous and heterogenous meetings) |

Contents: issues and concerns, tenor Group dynamics: atmosphere, interaction, communication style, forming of subgroups, conflicts, level of participation |

In addition to the usual scientific roles of data collector, analyser and descriptor, the researcher also took on several additional roles such as facilitator, teacher and Socratic guide. For example: VB acted as facilitator when bringing the residents and other stakeholders together in a heterogeneous meeting creating conditions for genuine dialogue. She played the role of teacher when she explained the experiences of various stakeholders towards one another. She played the role of Socratic guide when continually asking the Taste Buddies about their dreams about the meals and their – initially latent – ideas for improvement. When the group got bogged down in negative emotions, the researcher would bring in new vitality, by, for example, introducing creative tasks. These roles were dynamic and constantly changing, flowing with, and sometimes against, the dynamics in and between the participants.38, 39, 40 Member checks are central to collaborative action research. Feedback on the findings not only helps to consensually validate findings, but also prevents exploitation and fosters the transference of some ownership and control to the participants.

Later, once the project had ended, a secondary analysis of all data and analyses aimed to explore the possibilities of collective action as a vehicle for empowerment in the context of a residential setting with older people. Both authors analysed the interview transcripts, the field notes and logbook of the facilitator. The analysis was open to let issues emerge from the data. The analysis started with labelling text fragments per stakeholder group (clients in the action group, kitchen staff, restaurant staff, client council, team leaders and managers) followed by a comparison of the themes emerging in each stakeholder group. In the analysis, the focus was on the process of involvement and empowerment, (potential) conflicts and partnerships among and between groups, the role of the facilitator and collective actions. The authors discussed their themes until consensus was reached.

The Medical Ethics Committee of the VU Medical Centre approved the application of the PARTNER approach in long‐term case facilities. Care was taken to prevent overburdening and disempowerment of clients for example by introducing extra pauses when needed.

The Taste Buddies and their partners

The Taste Buddies and their relational empowerment

Initially, the Taste Buddies discussed a broad set of subjects for improvement. These included not feeling at home, not being able to go out, feeling dependent, experiences of loss and grief and not knowing one's neighbours. One theme stood out as particularly meaningful for them and was constantly recurring in the action group meetings: the meals. Action group members were dissatisfied with the meals. They saw dinner time at this home as messy and chaotic and felt that the food was of poor quality. They repeatedly stressed how important meals were: ‘It's the only time of the day when you have a nice get‐together. Dinner time means everything to me’ and: ‘It's a very important part of our lives, it really is!’ They shared their dissatisfaction by telling anecdotes, in minute detail, over and again. Meals were certainly not high on the local manager's list of priorities; he was more concerned with care‐related topics. However, this manager was aware of the complaints about the meals and was open to suggestions as to how meals could be improved.

The journey taken by the Taste Buddies did not simply go from having little influence straight to becoming involved. The dynamics were capricious and fluctuated. Initially, their interaction amounted to nothing more than a careful exploration of shared experiences about meals and downplaying anything negative. The group then began to feel more comfortable with each other and felt empowered by discovering that their discontent about meals was mutual. One of the ladies: ‘I'm glad I now hear there are more people who think the same way about the meals. I didn't dare say anything about it before. Honestly. I didn't dare to: I thought it was just me.’ However, constantly sharing negative experiences resulted in stagnation. The colourful collage the group made together put an end to negativism and the downward spiral because they had to envision the ideal situation in which anything was possible. There was a renewed sense of joy and a belief that they actually could succeed in getting meals improved. The Taste Buddies began to express an activist attitude, as the following statements illustrate: ‘We're not asking for perfection, just for improvements!’ and ‘I don't want to be proved right, I want something to be done about it.’ The group had learned, in a very natural way, how to transform their discontent into constructive advice for practice improvement. The group finally succeeded in turning their discontent into constructive advice.

Over time, these individual participants developed into a cohesive group in which they supported each other to keep going. Whenever one of them expressed doubt about the feasibility of their dreams, the others gently motivated her to stay positive. Trust was an important aspect of their process, as they had found a place in this group where they could speak freely about their concerns and dissatisfaction. This is reflected in the quote from one of the ladies when assuring her fellow participants that criticism is acceptable in the mutual encouragement of the group: ‘After all, we're here by ourselves, we can talk freely about this.’ The Taste Buddies admitted that criticising the food in public in front of other residents made them feel uncomfortable. One said: ‘I don't dare to complain about it, in that big restaurant…No, I can't do that.’ However, this group felt that during their meetings, their conversations were ‘among themselves’.

Engaging other parties, working towards partnership

For the kitchen and restaurant staff who came together in three separate meetings, the project was an opportunity to share their ideas about the meals with each other. It turned out that other issues and values underlay the subject of meals, such as the meaning of responsibility and good communication. Early in these meetings, participants were critical and negative about developments in the organization and their own lack of influence. For example, some restaurant staff pointed out that the kitchen staff did not appreciate their ideas for improving dinner time: ‘Then you get tension, like: mind your own business.’ A positive approach was used by the researcher for these meetings: the participants were asked to think about what could be done to make improvements and about what they could do to contribute towards the well‐being of clients. Furthermore, the facilitator introduced the participants in these groups to the issues and ideas of the Taste Buddies. They soon realized that they shared the same concerns and dreams. ‘Yes, we agree with the residents’ complaints, and we see the same opportunities for improvement.’ (restaurant staff). This made the staff feel that the residents were actually behind them, that they had the same goal, and that they could work on the problem together.

These homogeneous groups brought about a basis for partnership between the Taste Buddies and the other groups. They discovered common ground as they all wanted to improve the meals and to contribute to the well‐being of the clients in this residential care home. Positive support from the local manager and team leader towards the Taste Buddies was clear during the first heterogeneous meeting between them all. The team leader expressed her sympathy: ‘I do see the problems you have, and it also bothers me. We also want to change things.’ The manager's response was even stronger: ‘You're not a hundred percentage right, but a thousand.’ Both acknowledged that the Taste Buddies were right to complain and express their concern about the meals, and they encouraged them to talk to other groups as well.

So, in the final heterogeneous meeting, the Taste Buddies, kitchen staff, team leader, local manager, resident council members, volunteers and restaurant staff all got together to share their views. They first discussed the perspectives and values of the Taste Buddies as reflected in pictures they had taken. These pictures stood for the issues they had with the meals and were accompanied by salient captions. The participants recognized these issues very well. For example, one of the kitchen staff said: ‘Yes, that's something we often talk about, that the combination [of different parts of the menu] is not always good.′ The professionals came up with their own examples of these issues and discussed their dissatisfaction about the meals. There was openness about these critical remarks and about the wishes for improvement. The result was a feeling of mutual understanding and recognition, and this led to the participants arriving at agreements about practice improvements. A member of the kitchen staff added: ′We totally agree with the residents. If they're happy, we're happy.′ The managing director concluded: ′It's our job to keep you [residents] satisfied.′

Partnerships developed through these heterogeneous meetings and focused on a number of different aspects: discovery of common ground; recognition and mutual understanding of underlying values; all parties felt acknowledged for their ability to contribute; and the discovery that clients and professionals can be allies (and therefore partners) in creating practice improvements. Another important feature of this partnership development is the ownership and empowerment of the clients, the Taste Buddies. Instead of a situation in which the wishes and needs of clients are acknowledged and professionals then take over to implement practice improvements, the Taste Buddies were constantly approached as partners. They did not have to give up their sense of ownership of the project. This was supported by the researcher, as in the heterogeneous meetings she encouraged the participants to look for opportunities to implement practice improvements that involved an active role for the Taste Buddies. As clients were the owners of this project, they were the ones who directed the solutions, albeit in partnership with other stakeholders. This prevented a more one‐sided medical or health‐oriented solution to the discontent about the meals, and helped to focus on the contextual and social aspects brought fore by the clients.

Shared ownership, reassignment of responsibilities

The Taste Buddies became co‐managers, in the sense that they had real influence. These residents, who had initially been cautious about expressing their experiences, now considered it their responsibility to stand up for the other residents, as illustrated in the following quote: ′Yes, it [issues and concerns of residents] has to be brought up, because they [the organization] have to know what to do.’

The relationship between the taste Buddies and the other residents is another form of partnership that emerged during this project. The Taste Buddies felt it was their responsibility to check whether the other residents also shared their concerns. Informally, they validated their ideas: ‘I've put my feelers out to find out if the other residents also want change.’ Later in a gathering for all residents, the Taste Buddies presented their ideas for improving the meals and spoke with the other residents about these ideas to establish whether they were on the right track or not. The other residents were generally very positive about the ideas and efforts made by the Taste Buddies. Only a few residents expressed disapproval of this project because they did not believe that there was a problem with the meals at all. This discussion meeting was a supportive experience for the Taste Buddies because they learned that their efforts to get the meals improved were also meaningful to others. Later, positive responses from fellow residents were felt as encouragement to continue: ′If residents say that the food has improved a bit, then I think: Well, look what we have achieved!’

However, as the project proceeded, this partnership between the Taste Buddies and the other residents turned out to be a delicate one. The Taste Buddies felt the relationship with the other residents was supportive when the others were positive about the practice improvements. However, on the odd occasion when the meals were not tasty or something had gone wrong with the meals, some of the other residents went to the Taste Buddies to complain. The Taste Buddies found this a bit of a problem because they felt as though the other residents were now holding them responsible for the quality of the meals. They discussed this with the team leader and here again found a partnership. Together, they concluded that the team leader would have to tell all the residents exactly what they could expect from the Taste Buddies, and that residents with complaints about meals should also speak to him as team leader. The Taste Buddies felt supported by this action.

This process of building a partnership between the Taste Buddies and professionals demonstrates that identities and relationships shifted and that these groups developed trust, openness and mutual understanding about values. The Taste Buddies were therefore not only successful in terms of the concrete action they brought about, but also in terms of bringing about a change in their own perceptions of self and how they were seen and approached by their immediate environment.

Conclusion and discussion

In the case example presented here, a care‐ethics approach to user involvement appeared to be a means to increase the involvement of residents in long‐term care. The process led to their empowerment and also partly to an improved quality of life, here, for example, freshly cooked meals, a wider choice on the menu and a more pleasant atmosphere when dining. This related directly to the residents who formed the action group but also indirectly to the wider resident community through the practice improvements that resulted from the residents’ involvement and actions. The process also enhanced the development of partnership relations among residents, workers, managers and volunteers, and helped create an open climate.

This case example demonstrated that empowerment is a capricious and paradoxical process; it is fluid, often unpredictable and changeable over time and place.40 Rather than being ignored, tension or conflict should be discussed out in the open.41 In this case example, the facilitator supported the residents and helped to foster the group dynamics within the action group and with other parties. The facilitator was in a position of multiple partiality towards all parties involved, without being in a power position towards clients in the organization (e.g. being a care worker or manager). This prevented the organizational logic from dominating the process. It raises the question as to whether care workers or volunteers are willing and competent to act as facilitators, and whether they are in the position to relate to all stakeholders. We expect at least some training through an action–reflection cycle is needed for people to take up this role of facilitator. In developing facilitating skills, one issue that deserves attention is the precarious balance between directing and stimulating the action group and letting ownership develop in the group.

The care‐ethics approach to involvement assumes that residents and professionals go through a process of relational empowerment34, 35, 42: they start to share their experiences and values through dialogue, and while doing so they develop mutual trust and openness, a positive self‐identity and feeling of belonging. The managers, team leaders and staff of the organizations where we fostered this process were quite open to resident involvement. This open attitude on the part of managers and professionals will not be found in every organization, and resistance to change will have to be overcome. Further research is needed to gain an insight into the development of partnership between clients and professionals by means of the care‐ethics approach to user involvement.

We found that despite their advanced years, old residents were eager to join our projects. We also found differences in their willingness to join. Some were not interested at all, some developed an interest with time and some were triggered immediately. The extent to which people are willing to be involved could be closely connected to their biography.43 More research is needed to understand the intrinsic motivation of clients to participate, connected to their life history, experiences with living in a care institution and other possible factors. Other points for discussion include the feasibility of our care‐ethics approach in long‐term care settings with other vulnerable client populations (e.g. people with dementia, psycho‐geriatric and/or psychiatric illness or with severe physical impairments) or marginalized groups of people (e.g. migrants, gay people). The context and stakeholders in the presented project were in favour and open to user involvement. In order to gain more insight in the feasibility of the PARTNER approach to user involvement in long‐term care, further research is recommended in circumstances less favourable.

We conclude that a care‐ethics approach to user involvement fits with and builds on the need for connectedness and dialogue between older residents and others in the field of long‐term care. Care‐ethics stimulates collective action via a client action group and the development of partnership relations.

References

- 1. Barnes M. Care in Everyday Practice. An Ethics of Care in Practice. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilroy R. Why can't more people have a say? Learning to work with older people. Ageing & Society, 2003; 23: 659–674. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dewar BJ. Beyond tokenistic involvement of older people in research—a framework for future development and understanding. International Journal of Older People Nursing in association with Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2005; 14: 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baur VE, Abma TA, Widdershoven GAM. Participation of marginalized people in evaluation: mission impossible? Evaluation and Program Planning, 2010; 33: 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baur VE, Abma TA. Resident councils between life‐world and system: is there room for communicative action? Journal of Aging Studies, 2011; 25: 390–396. [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Dweyr C, Timonen V. Rethinking the value of residents’ councils: observations and lessons from an exploratory study. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 2010; 29: 762–771. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barber B. Strong Demsocracy. Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 8. In‘t Veld R. Knowledge Democracy. Consequences for Science, Politics and Media. Heidelberg, Dordrecht: Springer, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006: CD004563. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004563.pub2. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williamson C. Toward the Emancipation of Patients. Bristol: Policy Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mol A. The Logic of Care. Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. New York: Routledge, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnes M, Cotterell P (eds). Critical Perspectives on User Involvement. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sevenhuijsen S. Citizenship and the Ethics of Care. New York: Routledge, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mackenzie C, Stoljar N (eds). Relational Autonomy. Feminist Perspectives on Autonomy, Agency and the Social Self. New York: Oxford University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tronto J. Moral Boundaries. New York: Routledge, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Held V. The Ethics of Care – Personal, Political and Global. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bovaird T. Beyond engagement and participation: user and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 2007; 67: 846–860. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dunston R, Lee A, Boud D, Brodie P, Chiarella M. Co‐production and health system reform. From re‐imagining to re‐making. The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 2009; 68: 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karpowitz CF, Raphael C, Hammond AS. Deliberative democracy and inequality: two cheers for enclave deliberation among the disempowered. Politics & Society, 2009; 37: 576–615. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nierse C, Abma TA. Developing voice and empowerment: the first step towards a broad consultation in research agenda setting. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 2011; 55: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abma TA, Baur VE. Seeking connections, creating movement. The power of altruistic action. Health Care Analysis, 2012; doi:10.1007/s/10728‐012‐0222‐3. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baur V, Abma TA, Boelsma F, Woelders S. Pioneering partnerships. Resident involvement from multiple perspectives. Journal of Aging Studies, 2013; 27: 358–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Isin E, Wood P. Citizenship and Identity. London: Sage, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giddens A. Modernity and Self‐Identity, Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams L, LaBonte R, O'Brien M. Empowering social action through narratives of identity and culture. Health promotion international, 2003; 18: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rappaport J. Empowerment meets narrative: listening to stories and creating settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 1995; 23: 795–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barnes M. Deliberating with Care: Ethics and Knowledge in the Making of Social Policies. Inaugural Lecture. University of Brighton, 2008. 24 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yanow D. Assessing local knowledge. Deliberative policy analysis: understanding governance in the network society In: Hajer M, Wagenaar H. (eds) Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003: 228–246. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gadamer HG. Wahrheit und Methode. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Widdershoven GAM. Dialogue in evaluation: a hermeneutic perspective. Evaluation, 2001; 7: 253–263. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Young IM. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abma TA. Voices from the margins: political and ethical dilemmas in evaluation. Canadian Review of Social Policy/Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale, 1997; 39: 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baur VE, Abma TA, Baart I. ‘I stand alone’. An ethnodrama about the (dis)connections between a client and professionals in a residential care home. Health Care Analysis, 2012; doi: 10.1007/s10728‐012‐0203‐6. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gilson L. Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Social Science and Medicine, 2003; 56: 1453–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. VanderPlaat M. Locating the feminist scholar: relational empowerment and social activism. Qualitative Health Research, 1999; 9: 773–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Christens BD. Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 2011; 50: 114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prilleltensky I. The role of power in wellness, oppression and liberation. The promise of psycho‐political validity. Journal of Community Psychology, 2008; 36: 116–136. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hyung Hur M. Empowerment in terms of theoretical perspectives: exploring a typology of the process and components across disciplines. Journal of Community Psychology, 2006; 34: 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mertens DM. Transformative Research and Evaluation. New York: The Guilford Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mackewn J. Facilitation as action research in the moment In Reason P, Bradbury H. (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. Participative Inquiry and Practice. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2008: 615–629. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baur VE, Abma TA. The Taste Buddies: participation and empowerment in a residential home for older people. Aging & Society, 2011; 32: 1055–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rappaport J. In praise of paradox: a social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 1981; 9: 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nierse C, Schipper K, van Zadelhoff E, van de Griendt J, Abma TA. Collaboration and co‐ownership in research. Dynamics and dialogues between patient research partners and professional researchers in a research team. Health Expectations, 2011; 15: 242–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]