Abstract

Background

The involvement of patient representatives in health technology assessment is increasingly seen by policy makers and researchers as key for the deployment of patient‐centred health care, but there is uncertainty and a lack of theoretical understanding regarding the knowledge and expertise brought by patient representatives and organisations to HTA processes.

Objective

To propose a conceptually‐robust typological model of the knowledge and expertise held by patient organisations.

Design, data collection and analysis

The study followed a case‐study design. Data were collected within an international research project on patient organisations' engagement with knowledge, and included archival and documentary data, in‐depth interviews with key members of the organisation and participant observation. Data analysis followed standard procedure of qualitative analysis anchored in an analytic induction approach.

Results

Analysis identified three stages in the history of the patient organisation under analysis – Alzheimer's Society. In a first period, the focus is on ‘caring knowledge’ and an emphasis on its volunteer membership. In a transition stage, a combination of experiential, clinical and scientific knowledge is proposed in an attempt to expand its field of activism into HTA. In the most recent phase, there is a deepening of its network of associations to secure its role in the production of evidence.

Conclusions

Analysis identified an important relationship between the forms of knowledge deployed by patient organisations and the networks of expertise and policy they mobilise to pursue their activities. A model of this relationship is outlined, for the use of further research and practice on patient involvement.

Keywords: health technolgy assessment, knowledge networks, patient and public involvement, quality of life in dementia

One of the most significant changes in the organization of health care in the past two decades has been the increase in calls and attempts to involve users and publics in the processes of decision making. The application of forms of patient and public involvement (PPI) in healthcare decision making is seen to be able to make services and interventions more responsive to the needs of the patients and more aligned with public views on aspects of healthcare organization such as priority setting. It is argued that PPI can address the ‘legitimacy problem’ of a wide range of healthcare institutions,1 but there is still little knowledge about the relationship between procedures, processes and outcomes of PPI: Who and how to involve, for what reasons, in which situations?

Health technology assessment (HTA) is identified as a key domain in this arena because of how it underpins much of the knowledge and evidence that is brought to bear in healthcare decision making. Some researchers have advocated that patient‐focused HTA should reinforce the implementation of patient‐centred care through the systematic evaluation of evidence on relevant preferences and views.2 A recent literature review on patient and public involvement (PPI) in HTA processes found that patient and public representatives are mainly involved to provide evidence of needs and perspectives on the evaluation of technologies, but there is no systematic conceptualization of the value and role of such contributions.3 An international survey of PPI practices found that while there is evidence to suggest PPI procedures are widespread, HTA organizations are unclear about how to share knowledge about their activities and what the value of that knowledge is for other institutions.4

These uncertainties are underpinned by a lack of theory regarding the knowledge and expertise brought by patient representatives and organizations to HTA processes. Presently, patients' involvement in HTA is justified by the need to include ‘experiential knowledge’ of living with and managing an illness in the evaluation of the clinical, social and ethical effects of using a healthcare technology.5 Because illness experience varies across individual, social and cultural variables, there have been increased calls to systematize the integration of this type of knowledge by conducting primary or secondary research on patient perspectives.3, 6 To a significant degree, these proposals aim to address the ambiguous status of individual patients' perspectives both in HTA agencies and the social sciences, where some have argued that ‘experiential knowledge’ cannot be a robust base to evaluate the worth of research or technology.7

In this work, I argue that research on patient involvement in HTA should shift from focusing on individual, embodied knowledge, derived from living with an illness, towards an understanding of knowledge as amassed and deployed by networks of variable complexity. Indeed, in Borkman's original formulation of the concept of ‘experiential knowledge’, expertise was derived from the collection, comparison and sorting of individual experiences in self‐help groups; it was collectively produced and distributed across members of the group.8 Although such ‘experiential knowledge’ is usually seen in opposition to professional knowledge, particularly with the emergence of health social movements that specifically challenged established expertise from the 1960s,9 patient organizations have diversified the range of networks in which they participate10 and expanded their repertoire of knowledge‐related activities, increasingly collaborating across expertise lines.11 In our cross‐national, European study of patient organizations' involvement in knowledge generation, dissemination and use, we have found that condition‐focused organizations increasingly assume a hybrid epistemic identity, by articulating the collection and shaping of experiential knowledge with credentialed knowledge, some of them becoming part and parcel of networks of established expertise.12 Publicly assuming, this hybrid epistemic identity provides some patient organizations and their members with a capacity to intervene in and shape ‘evidence‐based’ policy environments, including their participation in HTA research and forums, while others remain attached solely to their ‘experiential knowledge’.

This work aims thus to contribute to the understanding of the processes by which groups or citizens become involved in public issues around health technologies13, 14, 15 by asking two related questions: (i) What knowledge‐related activities are patient organizations involved in? and (ii) How are these knowledge activities related to the networks in which the patient organization is embedded? In the paper, I will address these questions by using the case of the Alzheimer's Society (AS), the leading patient organization for persons living with dementia and their carers in England and Wales. The case was integrated in the European study referred to above and described in the Methods section and is used here because it represents an instance where high involvement in shaping research in HTA is associated with a strong historical integration in expert and policy networks both nationally and globally. The relationship between involvement and network integration shapes the organizations' epistemic identity: how organizations construct their own role as knowledge producers; the value they ascribe to knowledge; and their understanding of the value and relationship between different types of knowledge. Below, I explore how the AS has actively transformed its epistemic identity by mobilizing, extending and deepening collaborative links with clinicians, researchers and policy makers. This entailed questioning its sole reliance on ‘experiential knowledge’ as a basis to participate in the public shaping of dementia policy, and pursuing instead a hybrid identity that values the combination of experiential, clinical and scientific knowledge forms. In the Discussion, I will suggest that the case of the AS should be placed within a typology for patient and patient organization involvement in HTA that could, with basis on more research, guide analysis and integration of users' views in HTA.

Methods

The paper is based on research undertaken as part of a 3‐year international collaborative project entitled European Patient Organizations in Knowledge Society (EPOKS) which investigated patient organizations' involvement in the production of knowledge through a variety of case studies across national contexts and condition areas. In the project, case studies provided an inductive understanding of complex links between activism, knowledge and networks and helped us identify dimensions, conditions and relationships that underpin different forms of activism.

This work draws on a more detailed examination of single case study. A case study is usually defined as a detailed exploration of a single event, process or setting. Recognized as a crucial methodology in the social sciences and as integral to social science reasoning,16 case study research aims to use cases to tease out and identify dimensions, conditions and relationships within social phenomena. As such, case studies are also widely recognized for how they support the identification of previously ignored dimensions and relationships, having been the basis of key investigations in the history of the social sciences. Case studies provide an inductive understanding of complex causal links and of the conditions under which they might be deployed. Case studies may, however, suffer from selection bias where the choice of case is not explicitly articulated in relation to previous theory.

The data collected for the case study included: (i) archival data relating to the history of the organization between 1979 and 2013, held in the main offices of the AS in London; (ii) media archives collected through the data base FACTIVA relating to the AS (1979–2013); (iii) documentary data relating to the knowledge‐related activities pursued by the organization, provided by the AS or collected through their website; (iv) in‐depth interviews with key actors within the organization focusing on the role of knowledge and evidence in the activities and governance of the organization (n = 8); (v) ethnographic observation of events – conference, campaign actions, etc. – organized by the organization.

The analysis of the data for the case study presented in this work followed an analytical induction approach, a species of case‐based reasoning whereby instances are outlined and analysed in close and iterative relationship with the formulation of hypotheses.17 This entailed the use of (i) historical methods to map main events – the turning points – of the development of the organization, (ii) standard qualitative analysis techniques of constant comparison, thematic coding and deviant case analysis to characterize the knowledge activities pursued by the organization, and (iii) analysis of the institutional networks in which such positions are embedded at different phases of the development of the organization. This work was aided by the use of NVivo software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia).

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Applied Social Sciences, Durham University, drawing on guidance from the Economic and Social Research Council and the European Commission. Due to the public profile of the interviewees, it was agreed that that they would not require anonymization of transcripts but would have access to the final transcript used in analysis. All the other data collected were in the public domain.

Results

In this section, I explore the dynamic relationship between the forms of knowledge assembled and deployed by one patient organization and the networks of expertise and policy it mobilized to pursue its activities. I identify three phases of this dynamic in the history of the AS. In the first period, the AS established its epistemic identity around ‘caring knowledge’ by drawing on its volunteer membership, links with clinical specialists and support from the State. In a transition stage, the AS re‐articulated its identity as a combination of experiential, clinical and scientific knowledge in an attempt to redraw its relationship with volunteers and to expand its field of activism into HTA. In the most recent phase, the AS deepened and expanded its network of associations to secure its role in the production of evidence that is brought to bear in health policy making.

Becoming a carer organization (1979–99)

Established in 1979 as the result of the cooperation between two former carers and two clinicians, the then named Alzheimer's Disease Society (ADS) set its mission to be the provision of carer mutual support and of information on the relatively less known illness, to members and the public. Supported by the newly established third‐sector grants from the Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS), the ADS quickly developed its care services into the mid‐1980s. In 1981, the ADS received its first grant from the DHSS, which enabled the appointment of the first Development Officer and for paying the running costs of a small office. This was key to its development in terms of branches and membership and its establishment in the public sphere, through features in the news and TV documentaries (e.g. ‘Suffer the Carers’, 1982). The growing reliance of the ADS on government grants is attested by the fact that in 1985, DHSS grants accounted for 85% of the income of the organization. This supported further expansion, but also brought organizational uncertainties which were compounded by a 1987 audit on the DHSS which found ADS' accounting not to be within the ‘standards of accountancy’.18 This prompted a ‘major re‐organisation’ (ADS Annual Report 1988) and streamlining of management between 1988 and 1991.

The expansion of the volunteer‐based structure of the organization supported its growing awareness raising activities – the ‘Alzheimer's Awareness Week’ – with targeted media interventions. This in turn fuelled the information providing role of the organization, particularly through its newly established public helpline. For this, it relied on its ‘medical and scientific advisors’, who would ‘fill the gaps’ as they emerged through information requests (Interview Clive Evers, ADS Information Director 1989–2001, August 2009). The secure link with carers and volunteers was seen as a means to ‘produce political clout’ (Clive Ever Interview) in a context where changes in the organization of elderly care and social care were becoming more prominent in the UK. These factors worked together to make the ADS an important stakeholder in social care policy, and in 1990, the organization was a witness in the House of Commons Enquiry on Social Services.

By 1996, the ADS had 470 staff, 413 of whom were employed in the provision of care services. Caring and ‘caring knowledge’ defined the public identity of the organization: ‘we may not be able to offer the hope of a cure but we do offer unique understanding of caring issues, knowledge based on patient experience’ (ADS Annual Report, 1996–97; my emphasis). This epistemic identity underpins a variety of campaigning activities around the reorganization of community care services, the contribution of informal care to dementia management and consistent denunciations of the ‘healthcare lottery’ experienced by users of dementia services in the NHS and social care (The Times, 13 April 1996; ADS Annual Report, 1997–98: p. 4).

From carer to hybrid organization (1999–2005)

At the turn of the century, however, the now renamed AS, along with other organizations of the Alzheimer's movement,19 took its first step towards the integration of persons living with dementia (PWD) in the governance of the Society, its dementia services and information and research programmes. Publicly signalling this change, Harry Cayton, the AS Director at the time, urged the newly formed National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) to include the views of PWDs in the assessment of dementia drugs which had just been commissioned (Cayton, H. The Guardian, April 2000). However, this also represented a challenge to the blueprint of the organization and to the society's identity as a ‘carer's organisztion’. Further centralization of management and discussions on how to ensure standardized quality of service across branches, set out in the One Society Programme in 2003, was interpreted by some within the Society as a challenge to the role of the volunteer (usually ex‐carers) and to their experiential knowledge base (Interview with Eileen Winston, London, 11 October 2009; Rebellion at the Alzheimer's Society’, The Guardian, 13 October 2004).

Aiming to solve these tensions, the AS had to redefine its epistemic identity. Whereas previously this was underpinned by ‘experiential knowledge’, by 2003, the AS fully endorsed a more complex understanding of the organization as assembling a ‘unique knowledge [that] brings together the expertise of carers with the skills and insights of health and social care professionals and the discoveries of scientific research (Harry Cayton, ADS newsletter, August 1996: p. 2). Indicative of the epistemic hybridisation of the organization, this identity became key in the integration of the AS in the debates about HTA and the value of dementia drugs that were to affect the organization in the years to come. In particular, it enabled the organization to articulate and mobilize an extended network of actors that blurred expertise and membership boundaries.

Reckoning networks (2005–12)

Between 2005 and 2007, the AS was involved in a major public controversy over access to dementia drugs on the National Health Service. The controversy was sparked when NICE suggested in 2005 that dementia drugs might be taken off NHS prescription packages on the basis of their cost‐effectiveness value. From the start, the AS pointed towards the uncertainty of quality of life measurement in dementia that underpinned that evaluation, and attacked NICE's focus on positive changes in cognitive scores as outcome measures. Designing and conducting its own ‘research in the wild’20 in the form of a survey of their members, the AS argued that it was the maintenance of abilities and quality of life rather than cognitive enhancement that patients and carers valued.

In parallel with their engagement with NICE, the AS mobilized to form a public campaign on the issue – The Action of Alzheimer's Drugs Alliance – which comprised a heterogeneous set of institutions including Royal Colleges, universities, academic institutions and clinical centres. In October 2005, MPs from all parties passed an early motion in the House of Commons in which they ‘agree[d] with the Action on Alzheimer's Drugs Alliance that effective drug treatments for Alzheimer's disease should be available on the NHS and that NICE has failed to consider the important concerns […] about its draft guidance’.

In view of this, NICE ordered a recalculation of the available data and in January 2006 published a new recommendation that cholinesterase inhibitors should be available for patients with moderate dementia only. They had nevertheless still not taken into account the issue of quality of life measurement, which motivated the AS to join clinicians, researchers and manufacturers in appealing the decision. The appeals were rejected, and clinicians withdrew from the coalition of challengers, leaving the AS to join the judicial review put forward by manufacturers. Mainstream and professional publications suggested that, by challenging NICE's methodology through the courts, the AS was undermining the regulator's public legitimacy in favour of commercial agendas.

In response to these losses and charges, the AS aimed to redefine its public identity by setting the agenda on national dementia strategy. This took the form of the commissioning and propagation of a series of expert reports on the state and future of dementia care, coordinated by sustained public demonstrations and political lobbying: the ‘Putting Care Right’ campaign (2007–12). The start of the campaign was marked by the publication of the Dementia UK 2007 Report, where the AS sponsored credentialized experts from the LSE and the University of Kent to produce an assessment of the prevalence and economic cost of various types of dementia, and of levels of provision across the country. This exercise not only included the AS in the scientific effort to produce accurate estimates of the prevalence of dementia, but also, and importantly, endorsed the organization's capacity to speak for a group with specific needs in health and social care. Well linked into institutions of political representation, particularly Committees of House of Commons and Lords, the AS combined this political capital with the scientific authority of the report to be included in the negotiations that led to the establishment of the National Dementia Strategy in 2009.21

Combining formal participation in these forums with public activism, the AS embarked then on an assessment and critique of the state of dementia care in the UK through a series of campaign and lobbying actions focusing on care homes (2008), hospitals (2009) and community settings (2011). All campaigns were supported by reports using in‐house quantitative research and a collection of personal accounts from carers and PWDs. It is clear that the use of systematic reviewing and social research methodologies supported the AS’ aim to speak for ‘systemic issues’ in the organization of dementia care, such as lack of specialized dementia care training and time‐based tasking in care homes. But of equal importance was AS’ use of personal accounts of experience of the issues. This combination exemplifies AS’ attachment to a hybrid epistemic identity, where the quantification of factors leading to institutional failure gains relevance and depth when paired with exemplars of personal experience.

However, the status of experience and experiential knowledge in the public activities of the AS was still an unresolved issue. Attributing the weakness of their arguments against NICE to the lack of methodological sophistication with which they had depicted the views of their members (Fieldwork data), from 2008 onwards, the AS linked with social scientists and other charities to produce, first a report on the diagnosis and management of dementia from the perspective of PWDs (Dementia out of the Shadows) and then, crucially, two pieces of research about the issue of measurement of quality of life in dementia (My name is not Dementia). Of the latter, the first was a literature review conducted by experts at the University of Kent which identified an undue focus on health‐related quality of life indicators in dementia research, particularly on cognition, and advocated the development of hybrid quality of life indicators that combine ‘objective’ with ‘subjective’ domains of well‐being.22

Such expert endorsement of the position of the AS in relation to the use of quality of life measurement in HTA was complemented by mixed methods research used to gather the views of ‘seldom heard groups’ in quality of life in dementia research.23 The AS suggested that the research showed that ‘people with dementia, even those with more severe dementia, do not automatically find their lives dominated by the condition itself and the impact that it has on their mental functioning’.23 This directly challenged the assumptions of standardized quality of life measurement and academic quality of life research in dementia, but it was not aimed as a confrontation. Instead, the strategy of the AS was to publicly disclose key uncertainties in research on quality of life in dementia24 and to align itself with a network of research and policy actors to pursue of a transformation of this field of research. This not only secured the AS’ place on the collective negotiation about research policy in dementia in the UK from 2010 onwards, through its membership of the Ministerial Advisory Board Group on Dementia Research, but also enabled it to influence the attention given to ‘hybrid’ quality of life indicators within that forum and in the programme of dementia research sponsored by the National Institute of Health Research.

Discussion

This case study report addresses a key issue in PPI in HTA and other instances of health policy making: How to conceptualize and understand the contribution of patient representatives and patient organizations in the generation and assessment of evidence? Current frameworks for integrating patients in HTA draw on the role of moral preferences and/or experiential knowledge in the clinical, social and ethical evaluation of health technologies.2 Often, however, this knowledge is conceptualized as embodied in individuals or articulated in their personal stories. This raises epistemological questions about the status of experiential knowledge in HTA.

In this work, I took as my point of departure the view that knowledge, including ‘experiential knowledge’, is generated and deployed by networks25 and that to understand one we have to understand the other. I have suggested that it is possible for patient organizations to reformulate their epistemic identity so as to value and pursue the cross‐linking between different forms of knowledge. As we have seen in the case of the AS, this is underpinned by a trajectory of mutual reinforcement between strengthening of networks and expansion of the repertoire of knowledge‐related activities of the organization. This dynamic enabled the AS to publicly expose core uncertainties in the measurement of quality of life in dementia and to actively shape the HTA research agenda on this issue. Importantly, it was because the AS explicitly investigated, in association with experts, through a variety of methodologies, the role of ‘experience’ in quality of life measurement that it was able to transform it into a matter of collective enquiry. In other words, experiential knowledge became a part of the question to be investigated, rather than simply the answer to the issue of patient involvement in HTA.

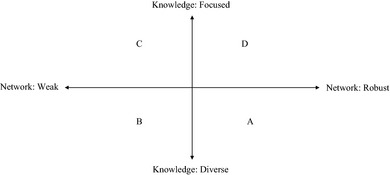

As I have indicated, the exploration of the case of the AS is not intended as a guideline on how to involve patient organizations in HTA. Rather, it represents a case within a space of possible epistemic identities that patient organizations might deploy in their interaction with HTA agencies. Based on this case, it is hypothesized that patient organizations’ epistemic identity is a function of the relationship between knowledge activities and network integration. Knowledge activities can be ranked according to diversity, from single focus in one area – experiential knowledge or biomedical research – to diverse domains of engagement. Network integration relates to the strength and heterogeneity of links with other actors, which can be operationalized as robustness. This model predicts four different types of epistemic identity for patient organizations (Fig. 1): robust hybrid (A), weak hybrid (B), weak focused (C) and robust focused (D).

Figure 1.

Epistemic identity as function of the relationship between knowledge activities and network integration.

Type A organizations are similar to the AS in its most recent phase of development, actively articulating their knowledge activities and their network alignment. Organizations of type B aim to diversify their knowledge engagement but show asymmetries in their ability to participate in some networks. They might, like the AS during its transition period, be locked into particular networks or unable to link effectively to others. Weak focused (C) organizations are those that invest in one type of knowledge – say, experiential knowledge – linked to one kind of network – members. Finally, robust focused organizations (D) are those able to incorporate their specific, unique knowledge form as a key contribution to a wider process of knowledge making. This could be ‘experiential knowledge’ when this is used specifically in the remaking of expert knowledge about particular illnesses, for example. This typology, as most in the social sciences, is not intended to be a discrete, rigid classification of species of organizations but rather as a conceptual tool to understand the patient organizations’ epistemic identities, and, importantly, their dynamic – how they might, as did the AS, traverse between types of organization in their development.

HTA agencies and researchers wanting to integrate patient representatives and patient organizations in assessment processes could draw on this tool to make sense of the contribution they can make. Framing their possible contribution only in terms of ‘perspectives’ and ‘experiential knowledge’ risks not only wasting relevant knowledge but also creating preventable conflict around PPI. Moreover, using this model would underpin PPI in HTA on a sound theoretical basis that acknowledges the diversity of forms of engagement of patient organizations with knowledge making. This would mean relying less on the expert‐lay boundary and delineate HTA as open‐membership ‘hybrid forums’ where experts, practitioners and patients collectively articulate the relationship between the evidence‐base and contexts of use of technology.26, 27

A key limitation of the typological model presented here is that it is based on a single case study. As explained in the Methods section, the model was devised through the use of analytical induction. This means that the model is not proposed as a finished conceptual tool. It is indeed one of the features of analytical induction that models are proposed as working hypotheses. As a form of case‐based reasoning, analytic induction requires constant testing and conceptual development. The aim is not to use cases to confirm or reject theories, but to use them as resources for further conceptual exploration. It is my hope that readers of this study will further test, expand and critique the model here proposed to gain a better understanding of patient involvement in the evaluation of health technologies.

Funding

The research was funded by the European Commission 7th Framework Programme within Science in Society initiative.

Conflict of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

I thank the staff of the Alzheimer's Society for their help with data collection. This manuscript gained from the helpful comments of Madeleine Akrich and Orla O'Donovan.

References

- 1. Lloyd K, White J. Democratizing clinical research. Nature, 2011; 474: 277–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Facey K, Boivin A, Gracia J et al Patients' perspectives in health technology assessment: a route to robust evidence and fair deliberation. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 2010; 26: 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gagnon M‐P, Desmartis M, Lepage‐Savary D et al Introducing patients' and the public's perspectives to health technology assessment: a systematic review of international experiences. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 2011; 27: 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitty JA. An international survey of the public engagement practices of health technology assessment organizations. Value in Health, 2013; 16: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Europe HE. Understanding Health Technology Assessment. Brussels/London: Health Equality Europe, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lehoux P, Williams‐Jones B. Mapping the integration of social and ethical issues in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 2007; 23: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prior L. Belief, knowledge and expertise: the emergence of the lay expert in medical sociology. Sociology of Health & Illness, 2003; 25: 41–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borkman T. Experiential knowledge: a new concept for the analysis of self‐help groups. The Social Service Review, 1976; 50: 445–456. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown P, Zavestoski S, McCormick S, Mayer B, Morello‐Frosch R. Gasior Altman R. Embodied health movements: new approaches to social movements in health. Sociology of Health & Illness, 2004; 26: 50–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baggott R, Allsop J, Jones K. Speaking for Patients and Carers: Health Consumer Groups and the Policy Process. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Basingstoke, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rabeharisoa V, Callon M. The involvement of patients' associations in research. International Social Science Journal, 2002; 54: 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rabeharisoa V, Moreira T, Akrich M. Evidence‐based activism: patients' organisations, users' and activist's groups in knowledge society. Biosocieties, 2014; 9: 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin GP. Citizens, publics, others and their role in participatory processes: a commentary on Lehoux, Daudelin and Abelson. Social Science & Medicine, 2012; 74: 1851–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lehoux P, Daudelin G, Abelson J. A response to Martin on the role of citizens, publics and others in participatory processes. Social Science & Medicine, 2012; 74: 1854–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Daudelin G, Lehoux P, Abelson J, Denis JL. The integration of citizens into a science/policy network in genetics: governance arrangements and asymmetry in expertise. Health Expectations, 2011; 14: 261–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ragin CC, Becker HS. What is a Case?: Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katz J. Analytic induction In: Smelser N, Baltes P. (eds) International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Hague: Elsevier, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Plummer J. How are Charities Accountable. London: Demos, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beard RL. Advocating voice: organisational, historical and social milieux of the Alzheimer's disease movement. Sociology of Health & Illness, 2004; 26: 797–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Callon M, Rabeharisoa V. Research, “in the wild” and the shaping of new social identities. Technology in Society, 2003; 25: 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Department of Health . Living Well With Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy. London: DOH, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Warner J, Milne A, Peet J. My Name is not Dementia: Literature Review: Alzheimer's Society. Alzheimer's Society, Location: London, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williamson T. My Name is Not Dementia: People With Dementia Discuss Quality of Life. Alzheimer's Society, Location: Alzheimer's Society, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bond J. Quality of Life and Older People. London: McGraw‐Hill International, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Callon M. Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St. Breuc Bay In: Law J. (ed.) Power, Action and Belief A New Sociology of Knowledge? (Sociological Review Monograph 32). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986: 197–233. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Callon M, Lascoumes P, Barthe Y. Acting in an Uncertain World. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moreira T. The Transformation of Contemporary Health Care: The Market, The Laboratory and The Forum. New York: Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]