Abstract

Background and objective

Children from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds are at risk of having developmental problems go undetected prior to starting school, and missing out on early intervention. Our aim was to explore the family and service characteristics, beliefs and experiences that influence the journey of families from CALD backgrounds in accessing developmental surveillance (DS) and early intervention services in south‐eastern Sydney, Australia.

Design, setting and participants

This qualitative study used in‐depth interviews conducted with 13 parents from CALD backgrounds and 27 health and early childhood professionals in Sydney. The Andersen Behavioural Model of Health Service Use (BM) was the underlying theoretical framework for thematic analysis.

Results and discussion

Family and service knowledge about early childhood development (ECD), community attitudes, social isolation and English language proficiency were dominant themes that impacted on the probability of families accessing services in the first place. Those that impeded or facilitated access were resources, extended family and social support, information availability, competing needs, complex service pathways and community engagement. There were variable practices of early detection through DS. Children from CALD backgrounds with developmental problems were perceived to miss out on DS and early intervention despite language delay being a key issue identified by participants.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of increased community and family awareness and professional training in ECD; better coordination of health and early childhood services, with simpler referral pathways to early intervention to prevent children from CALD backgrounds ‘slipping through the net’.

Keywords: culturally and linguistically diverse, early childhood development, health and early childhood services, parents, qualitative research

Introduction

The key to an individual's long‐term health, well‐being and social function is a solid foundation in early childhood development (ECD).1 Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) data demon‐strate that in Australia, around a third of children from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds starting their first year of school are ‘developmentally vulnerable’, which means that they have not acquired the necessary language, self‐help, socio‐emotional, cognitive, motor and/or behavioural skills they need to flourish in school and later life.2, 3 Risk is associated with English proficiency, with 22% of children from CALD backgrounds who are proficient in English being developmentally vulnerable (similar to the percentage for all children in Australia) compared to over 90% of children who are not proficient in English.2, 3

Identification of children early in the preschool years and timely referral to early intervention (including high‐quality early childhood education and speech therapy) has been shown to improve the developmental outcomes.1, 4, 5, 6, 7 The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the American Academy of Paediatrics recommend a system of universal developmental surveillance (DS) to facilitate early detection of developmental problems, promotion of ECD and timely referral to early intervention.8, 9 DS involves a careful history of parental concerns about their child's development combined with clinical observation and standardized tools.9 In New South Wales, of which south‐east Sydney is a geographic area, DS is undertaken over the first 4 years of life using the personal health record (‘Blue Book’) by child and family health nurses (CFHNs) and general practitioners (GPs).

International and Australian data have demonstrated that the practice of DS in primary health‐care services is suboptimal in terms of the proportion of families who access these services and the quality of DS undertaken.10, 11 Of concern, according to AEDC data, only a quarter of developmentally vulnerable children have their problems detected and receive any early intervention prior to starting school.12, 13 There is a paucity of research on risk factors that impact on access to DS and early intervention. If one examines the use of preventive health services generally, families from CALD backgrounds, particularly those with poor English proficiency, belonging to certain ethnic groups, lower socio‐economic status and lowerlevels of maternal education, have been found to have an inequitable access to these services.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 In addition, there is evidence that children from CALD backgrounds are at greater risk of having developmental problems go undetected even if they do access services due to language delays being attributed by health professionals to their exposure to more than one language at home.20

A recent Australian study of the broader parental conceptualization of preventive child health care found that parents consulted family members and early childhood staff about their developmental concerns for their children before accessing preventive health services. The authors recommended that future research should investigate the collaboration between primary health care and early childhood professionals around early detection of developmental concerns.21 This is supported by the literature that argues that early childhood settings such as supported playgroups and preschools provide an ideal opportunity for monitoring ECD, early detection of developmental problems through DS, and timely referral to early intervention services.19 In order to develop strategies to prevent children from CALD back‐grounds arriving at school with undetected and unaddressed developmental problems, we need to further explore access to DS and early intervention from a family, health and early childhood service professional perspective. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore the family and service characteristics, beliefs and experiences that influence the journey of families from CALD backgrounds in accessing DS and early intervention services in south‐eastern Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

We used the Andersen Behavioural Model of Health Service Use (BM) as the underlying analytical framework for this study.22 It has been used extensively since 1968 as an analytical model to define and measure equitable access to health care.22, 23, 24 This multilevel model defines individual and contextual characteristics that impact on access as ‘predisposing, enabling, need variables’ and ‘health behaviours’ that sequentially impact on the use of health services.22 ‘Predisposing’ variables are characteristics of an individual or their environment that exist before an individual's perception of a condition and influence the probability that an individual will utilize a service. ‘Predisposing’ variables include demographic variables (e.g. gender, ethnicity), social structure variables (e.g. education, socioeconomic status) and knowledge/beliefs around the condition.23, 25, 26, 27, 28 ‘Enabling’ variables reflect the individual and environmental means and resources which facilitate or impede access (utilization) of a service.27 Examples of enabling variables are individual and household wealth, availability and accessibility of a health service in the community, health policy and organization of a health service.27, 29

Predisposing and enabling components are necessary for the use of health services, but without a need, services will not be accessed. Need can be defined not only by a predisposition to a condition but also how the individual, family or community perceives it as important.23, 25, 26, 28 In addition, personal health practices of families and the process of care at the service level impact on service use and health outcomes.22 The BM has been adapted over the last 50 years to include concepts such as equity, potential and real access, efficiency, effectiveness and vulnerable populations.30 It has been used internationally in quantitative and qualitative studies of children's access to preventive health services.21, 23, 28 To our knowledge, this is the first time it has also been used to specifically examine access to DS and early intervention services in the health and early childhood setting.

Design

Setting

The project was undertaken in a socioeconomically disadvantaged area of south‐eastern Sydney in New south Wales, Australia, with a significant CALD population with 47% of the community having a language background other than English.31 Recent data have found that 22.4% of children from this area were developmentally vulnerable with only 5.9% of these children receiving any early intervention prior to attending school.32

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained through SCHN HREC ethics committee HREC # 12SCHN439.

Recruitment strategy

Parents/carers from CALD backgrounds who had a recent experience of raising a preschool‐aged child; and health and early childhood professionals who provided services to parents/carers including those from CALD backgrounds were eligible for inclusion in the study. An early childhood professional was defined as a professional who worked in family support, community development (with parents) and/or in early childhood education settings. Families were recruited through multicultural playgroups and parenting groups run through non‐government organizations who work with CALD communities. All professional interviews were undertaken first. There was purposeful sampling of professionals from a variety of government, non‐government, privately and publically run organizations, who worked in early childhood, health, education and disability. Health and early childhood professionals who were thought to be able to give a variety of important insights were identified by the project team through non‐government organizations, interagency groups, a primary health‐care organization and a children's hospital. The snowballing technique, using ‘word of mouth’ was used to identify additional participants where we asked professionals to suggest other professionals and parents/carers to approach. Purposeful sampling of parents/carers from differing cultural, linguistic and socioeconomic backgrounds, with varying degrees of service exposure (as identified by the professionals who suggested them), and experiences was also used. The project was promoted in the NGOs to parents/carers through a flyer and by professionals working in these NGOs, and potential parents were then asked their permission to be approached.

After participants were approached and agreed to participate, the purpose of the project was explained both verbally and in writing to each participant by the project officer. Interpreters were also provided on request by the participants. If the participant had a reasonable proficiency of English and also had an email address, the consent form was sent to them prior to the interview. Alternatively, they were given the consent form directly by the project officer, and interviews were arranged usually within a couple of weeks of agreement to participate. The consent form was reviewed at the beginning of the interview with an interpreter and always signed before the interview began. Questions about the interview being recorded were discussed also prior to interview and on the day. Written and signed consent was obtained from each participant. Participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity as data were to be stored in a de‐identified manner in a safe and secure environment. All participation in the study was voluntary. Participants were free to withdraw their consent at any time without any prejudice. No participants approached refused to be interviewed or withdrew their consent. Recruitment ceased when data saturation was achieved, and we had identified the ‘negative case’, individuals whose beliefs contradict those of the majority.33

Characteristics of participants

A total of 40 participants took part, 27 health and early childhood professionals and 13 parents. Participant characteristics are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. Parents/carers came from eight self‐identified ethnic groups. The majority were female. All were caring for preschool aged, and eight had more than one child. Five had a child with a developmental problem. Health and early childhood service professionals had a wide range of professional roles, but all were focused on working the CALD families with preschool children. They came from the non‐government sector, government sector (education, disability,health, childcare) and the private sector (GPs, childcare, local primary health‐care organization).

Table 1.

Parent/Carer characteristics

| Study number | Gender | Ethnicity | Data collection method |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F | Czechoslovakian | Individual Interview |

| P2 | F | Bangladeshi | Individual Interview |

| P3 | F | German | Individual Interview |

| P4 | F | Bangladeshi | Individual Interview |

| P5 | F | Bangladeshi | Individual Interview |

| P6 | F | Korean | Individual Interview |

| P7 | M | Iraqi | Group Interview (husband and wife) |

| P8 | F | Iraqi | |

| P9 | F | Greek | Group Interview (playgroup) |

| P10 | F | Italian | |

| P11 | F | Lebanese | |

| P12 | F | Iraqi | |

| P13 | F | Greek |

Table 2.

Health and early childhood professional characteristics

| Study number | Gender | Role | Sector | Data collection method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | M | Community Development | NGO 1 | Individual interview |

| S2 | M | Community Development | NGO 1 | Individual interview |

| S3 | F | Family Support Worker | NGO 1 | Individual interview |

| S4 | F | Family Support Worker | NGO 1 | Individual interview |

| S5 | F | Family Support Worker | NGO 1 | Individual interview |

| S6 | F | Senior Case Manager | NGO 2 | Individual interview |

| S7 | F | Child and Family Practitioner | NGO 2 | Individual interview |

| S8 | F | Child and Family Practitioner | NGO 2 | Individual interview |

| S9 | F | Coordinator of Children's Program | NGO 3 | Individual interview |

| S10 | F | Manager | NGO 3 | Individual interview |

| S11 | F | Director | Child Care 1 | Individual interview |

| S12 | F | Family support services | NGO 4 | Individual interview |

| S13 | F | Parent coach educator | NGO 4 | Individual interview |

| S14 | F | Manager Access | Disability (government) | Individual interview |

| S15 | M | Acting Manager Access | Disability (government) | Individual interview |

| S16 | F | Speech Pathologist | Disability (government) | Individual interview |

| S17 | F | Principal | Education (government) | Individual interview |

| S18 | F | Deputy Principal | Education (government) | Individual interview |

| S19 | F | Director & educator | Child Care 2 | Individual interview |

| S20 | F | Early Childhood Health Nurse | Health (government) | Group interview (S20 and S21) |

| S21 | F | Early Childhood Health Nurse | Health (government) | |

| S22 | F | Early Childhood Health Nurse | Health (government) | Group interview (S22 and S23) |

| S23 | F | Early Childhood Health Nurse | Health (government) | |

| S24 | M | General Practioner | Private Practice 1 | Individual interview |

| S25 | F | Nurse, Community Leader | Health (government) | |

| S26 | F | Project Officer | Primary Health Organisation | |

| S27 | F | General Practioner | Private Practice 2 |

Data collection

Data were collected between July and October 2013. Semi‐structured, recorded, in‐depth group and individual face‐to‐face interviews lasting 30–60 min with contemporaneous field notes were conducted using an interview guide (Box 1) developed by the project team. The interview guide was piloted on staff and family members of the project team. Details of interview type are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. Type of interview was determined by participant preference. One individual interview was not tape‐recorded due to participant preference, and one group interview was not tape‐recorded due to logistics of the play group. Three parents requested interpreters (Korean and Bengali). The project team consisted of four members of non‐government organizations (NP, JG, BJ and RK) with community development, social work and early childhood qualifications, as well as four child health professionals with extensive experience working with CALD communities (SW, VS, DP and JC). Interviews were undertaken by the project officer and other members of the project team. Three service professionals elected to provide an email response to the interview guide as they were unable to be interviewed due to their time constraints.

Box 1. Interview guides.

Interview guide for parents

What does child development mean to you?

What things help children develop? (prompt – what services)

What would you do if you were worried about your child's development? (Prompt: Where would you go? What services?)

How useful do you find services that support child development?

How would you make these services better?

Interview guide for early childhood and health professionals

How do you promote child development with families?

If you were worried about a child's development, how do you approach this with the family? (Prompt: what works and what doesn't?)

Where would you refer if you were concerned about a child's development?

How would you make these services better?

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and participants offered the opportunity to revise their transcript. Audiotapes were also reviewed against the transcripts by NP. Inductive thematic analysis was undertaken of transcripts, field notes and email responses. All project team members assisted with the coding of data to examine it for key themes and to compare coding. There was then discussion and consensus within the project team around these themes. Data collection and analysis of transcripts continued until no new themes or hypotheses emerged (data saturation). Deductive analysis was undertaken where the dominant inductive themes were arranged under the categories of the BM by the first author SW. This was cross‐checked by LK. Project team and participant feedback were then sought on the categorization to check coding validity. To assist inductive and deductive analysis, data were coded with NVivo 10 software.34

Results

Dominant themes

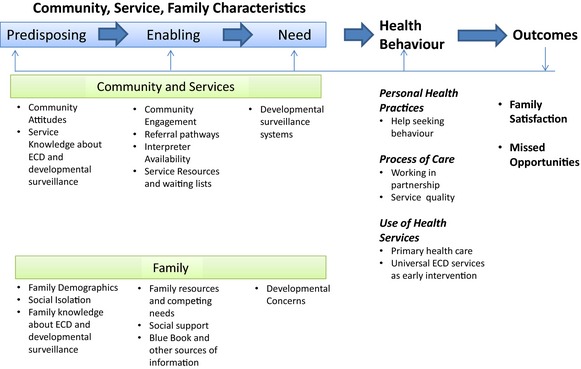

Figure 1 gives an overview of the dominant themes identified in the study through inductive analysis and their deductive categorization according to the BM. An example of the sequential and cumulative relationship between the components of the BM is illustrated in Box 2 using a composite from a number of family journeys.

Figure 1.

Adapted BM.

Box 2. The family journey.

I had no experience and I don't ‐ I didn't even know what's the services available for kids… (Predisposing) and just used to stay at home… at that stage we didn't know about autism (Predisposing) I discussed with other women from (home country) when we sort of got together in the friends gathering, oh he'll be alright when he goes to the school, (Predisposing) GP didn't pick up what's going on. (Predisposing). I couldn't spend lot of time with my daughter, sometimes busy with housework you know, because I was new and I was not too much expert in work so I have to do lot of thing I have to learn. (Enabling). We didn't give our daughter to any childcare at the time, because of our affordability we couldn't afford child care and we were a student visa at the time (Enabling) he (GP) just told us can she ‐ is she talking or? We say no but he didn't tell anything, just do the hearing test, yeah (Enabling). She had no blue book. (Enabling). We have to go to GP first, otherwise we can't go to paediatrician (Enabling). Language delay, which didn't have to do with the bilingual stuff (Need). Sometimes I take my daughter to some playgroups (Health Behaviours) We used to take her just to the GP for general check‐ups (Health Behaviours) …but he (GP) didn't pick up (Outcome) GP its was too disappointing. They need to refer us so they need to learn, they need to get some understanding of it, so (Outcome). If he would have the early interventions when he was two he would have progressed differently. (Outcome).

Predisposing, enabling and need characteristics identified

Predisposing characteristics

See Box 3.

Box 3. Predisposing characteristics – Quotes.

| Characteristic | Illustrative quotes from participants |

|---|---|

| Predisposing | |

| Community attitudes | And like, in my culture sometimes some of the people they think's okay. Your child is not normal, so called normal, because of your fault. (S2) |

| And I find that some CALD families don't let go, they just want to keep them home ‘til they're five and then start school. (S9) | |

| Family and service knowledge regarding early childhood development and developmental surveillance | I didn't have any actually idea how child develop, how their mentally or emotionally develop. I didn't have any idea because in our family, you know, I didn't have lot of ‐ I didn't see lot of children (P2) |

| I assume that when a child is born there is a certain amount of follow up that Hospitals or, you know, from a more medical sort of side of things is done to sort of monitor that development and you've got, you know, the blue book and those sorts of things. (S15) | |

| Family demographic characteristics | Because I can only exchange greetings in English and I can't do any in English with somebody and also I have some fear that I could be different because of my clumsy language so I avoid relating to Australians that much. (P6) |

| I find that a lot of time the father, the males are the one that, disagree to go for appointment, work comes first. (S12) | |

| Social isolation | So yeah after coming to Australia everything is new, yeah. You know different culture, different environment and I used to ‐ oh I had no relatives here. (P2) |

| Very big move you know like everything is new here. Moving from another country it's really a very big change and coping with everything, everything is new. (P4) | |

| Well most of the (X) community out there are very you know, they work … and they split shifts between themselves so they don't actually socialise. Their children are at home all the time. (S20) | |

Community attitudes

Community attitudes were perceived to impact on access to DS and early intervention. In some groups, terms such as ‘autism’ or ‘language delay’ were unknown, and for others, it was a source of shame and stigma to have a child with a disability. It was also perceived that there was reluctance by some families to use universal sources of early intervention such as early childhood education because looking after children was perceived to be the role of the family.

Family and service knowledge regarding early childhood development and developmental surveillance

Many parents from CALD backgrounds and some service professionals did not have a clear understanding of what constituted normal ECD much less about how to identify children with developmental issues through DS, whose role it was and where to go if they were concerned about a child. Those parents, who had a child with a developmental problem, described that comparison to other children made them aware there was an issue.

Family demographic characteristics

Ethnicity, English as a second language and other risk factors such as mental health, education and socioeconomic disadvantage were felt by participants to impact on the probability of accessing services. Previous adverse parental experiences with authority were also important. Professionals described a gender imbalance in English proficiency with the father often acting as an interpreter and filtering the information that the mother received. The father may also have power of veto in accessing services.

Social isolation

Social isolation was a significant issue for many parents from CALD backgrounds, especially for mothers. This isolation was worsened by the fact that many did not know about support and early intervention services such as supported playgroups. The fact that their own parents lived overseas or alternatively because the grandparents were the full‐time carers while the parents were at work compounded this. Certain groups of parents were perceived by professionals as being more socially isolated.

Enabling characteristics

See Box 4.

Box 4. Enabling characteristics – Quotes.

| Enabling | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Community engagement | You have a community leader so they spread it throughout the community where they come and they just have conversations and then you're able to get external presenters to come in and talk about the types of services. (S14) |

| I find that playgroup at the park's really good. Playgroup at the park, it's the best for any services that want to do playgroup because you're open to the community, we put signs up. And that's when you can approach the community to say, come on down, you can bring your kids along and have a little play, we're free. So that's how we get most of our families, especially at the park. We get about 40 families a week. (S12) | |

| Referral pathway | I think with some of our families, it's that actual you know, going to the doctor, getting a referral and then making that appointment and then going there. That is an issue with some families to actually make that physical oh I've got to go to the children's hospital, where do I go, what to do… (S18) |

| Interpreter availability | They didn't ask me or we didn't ask maybe, yeah, did you have interpreter or not. So everything deal ‐ we did in English. (P2) |

| Yes I was invited to come to the early childhood centre in the, in my area but in the first meeting (Information given to mothers at the maternity hospital.) they had an interpreter for me and that interpreter was too rushing and she asked me to say things very quickly and she intimidated me so I just didn't do it. (P6) | |

| Resources, competing priorities and waiting lists | We're talking about a community that's got no money (S20) |

| We didn't have like very regular time schedule, we had a very tight schedule instead and sometimes when my husband came home I go out for work because then my husband look after the baby and when I came back home, he goes back out for his study and then to his work, so I looked after my baby. (P5) | |

| The hardest thing I think, that we come up against is that you've identified that there's a need, you've identified that you've got a two year old that's not talking and, you know, you can try and work with Mum on doing stuff but I can't do a hearing test, I can't know if there's anything else cognitively going on and I can't go and get that kid into a hearing test until I've had a Paediatric referral so I have to wait three, six months for Paediatric assessment, then I wait a month to get the report back and the referral sent off and then I'm on a waiting list for hearing for the next three, six months. (S6) | |

| Social support | Like you know, it would be more helpful for me if my mum and dad stayed with me and give me some support, you know, but sometimes still I sometimes it's overwhelming for me. (P2) |

| So a parent might be concerned about their child, but there might be someone else in the family, like a grandmother or an aunt, who says there's nothing wrong and there's no need to do anything. (S16) | |

| Blue book resources | I really feel for my son because he's born in Bangladesh because at least if I had the (blue) book I knew that maybe why he's not doing that sort of talking and one year and two years but nothing to do he was born in Bangladesh. (P4) |

| The blue book's our core ‐ our personal health record is where everything starts. They bring it with them and they do ‐ we only do core visits at the clinic but those questions and that are there part of that developmental check and screening, we try and get them to do that when they ‐before they sort of visit.… I think they just see it as something they drag around with them. I'm not sure that they actually read it… (S20) |

Community engagement

Information sharing, culturally appropriate practice and building trusting relationships were described by professionals as key elements in community engagement for promotion of ECD, DS and early intervention. The importance of having multicultural health workers who have a better understanding of families' cultural perspectives was highlighted. In particular, community leaders who were perceived as experts on ECD in their CALD communities, such as multicultural workers, were influential in facilitating how parents access DS and early intervention services. However, it was pointed out that it was not essential for a professional to be of the same cultural group as long as families were treated with respect. Some services felt that they were not targeting CALD communities effectively. Others reported success through free, supported multicultural playgroups in public spaces and parent groups.

Referral pathways

The role of the GP as a gatekeeper of the health system was perceived as a barrier because the family may not go to their GP, their GP may not detect that there is a problem and/or may not know of referral options. In addition, there was a confusing duplication and lack of communication between early intervention services, inconsistent intake processes and ever changing, complex referral pathways. These were felt to be overwhelming for families from CALD backgrounds particularly when there was limited English proficiency and literacy.

Interpreter availability

Parents and services reported that interpreters and translated materials were not universally available. Experiences with interpreters were mixed with professionals describing their usefulness; however, some parents described a lack of sensitivity and felt intimidated by interpreters. Telephone interpreting, although helpful, was not used uniformly by services and was difficult to access when professionals were out in the field. Some parents would travel a long way out of the area to access health professionals who were from their own culture and spoke their language.

Resources, competing priorities and waiting lists

Parents and professionals described significant financial barriers for parents in accessing services that promoted ECD, in particular early childhood education and private speech pathology. In addition, there were long wait lists for publically funded services such as speech pathology and short consultation times for GPs. CFHNs described having less funding than acute services as they were not dealing with ‘sick children’. Parents/carers also described significant competing priorities for time and resources for families including other children, housework and the necessity in some families that the parents work long hours out of home.

Social support

Extended family networks were able to promote ECD within their families, and there were examples given of family members facilitating parents accessing DS and early intervention. However, there were examples given where family and community members could also act as a barrier by denying that a child had a developmental problem.

Use of the blue book and other family information sources

Parents used a wide variety of information on ECD and services: their friends, neighbours, the internet, books from the local library, newspaper articles and ECD professionals with varying success. Use of the personal health record or ‘Blue Book’ that promotes ECD, DS and early intervention in NSW was inconsistent by parents and professionals. It was mainly used for ‘vaccinations’ and documenting growth by parents, GPs and paediatricians. CFHNs were the only professional group to describe its importance for ECD and DS and early intervention. Families whose children were born overseas reported that they did not have a ‘Blue Book’, which contributed to their lack of awareness regarding ECD and services.

Need

See Box 5.

Box 5. Need – Illustrative quotes.

| Need | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|

| Developmental concerns | One of the biggest issues that we have with kids coming to school with not the language that they need and the understanding that they need because of their language issues… whether it's a developmental learning thing, whether its speech whatever so that's that's an issue for us but I would say, oh look at least a third of the children in Kinder I would be concerned that they're not at this stage. (S17) |

| When he string two words together, but never went over the next hurdle to form sentences. So we, again, doctors told us bilingual, it takes a bit longer, so we waited a bit longer, but it didn't change. (P3) | |

| Developmental surveillance | Not sort of jumping in too quickly but at the same token, don't letting it go on too long, because there could be a problem there, and we could be just chalking it up to a bilingual child. (S19) |

| We are not taught how to refer, where to refer, etc., the pathways are not as clear as say‐ antenatal shared care‐ which has their own website. (S27) |

Developmental concerns and developmental surveillance systems

Parents and professionals identified language, behaviour and school readiness as key concerns in relation to children from CALD backgrounds. Participants also reported a reliance of parents on the expertise of health and early childhood professionals to alert them of concerns. Only the CFHNs were confident in their ability to undertake DS. Other health and early childhood professionals described the importance of taking time to observe children as a team but had variable and non‐standardized approaches to monitoring child development. For example, one health professional assessed a child's comprehension by asking them to ‘breathe in, breathe out’, and if child stares blankly at the ceiling, ‘something is not right’. Those professionals who used checklists felt that they helped families to see that children are on or off ‘track’.

Many parents reported that professionals missed their child's language delay by attributing it to bilingualism (being exposed to two languages) rather than impairment. Many professionals reported that they did not have sufficient training in ECD, detection of developmental problems, especially in bilingual families and where to refer. There were also examples of ‘inaccurate detection’ by early childhood professionals where children were being inappropriately flagged as possibly having a language delay or autism without standardized DS, which caused unnecessary parental distress.

Health behaviours

See Box 6.

Box 6. Health behaviours – Illustrative quotes.

| Health behaviours | Illustrative quotes from participants |

|---|---|

| Personal health practices | |

| Help seeking behaviour | I talk about my own culture most parents they want to believe that their child are the best, the healthiest, that they're the most intelligent. Maybe it's a feel of guilt that they don't want to accept there is a problem, or a feel of shame. (S4) |

| I think what I've been really surprised with is that families are often really intuitive and will come to you when they feel comfortable and say – ‘I'm concerned. I have this worry’. (S5) | |

| Process of care | |

| Working in partnership | In my experience gaining trust is the first thing and if I go in with an agenda, it doesn't, it often doesn't really work (S7) |

| I'm here to be supportive for the families but my ultimate responsibility is the children that are in my care (S13) | |

| Service quality | I feel like one, they're (GPs) not very thorough in filling it (blue book) out. So even if they did do what they were to do, they don't always fill out their blue books properly. Which then sends the parents into a spin because they feel like you did it but you didn't do it because you didn't complete it. So then they come here and get it repeated. (S20) |

| So if they can admit that they don't know… And that's a problem for doctors, if they can admit then they could put you on another path. Even mention that there is something, like a developmental clinic. No doctor mentioned that (P3) | |

| Use of services | |

| Source of primary health care | I normally ask them to see their doctor, their GP, to check the child development. Or for the younger children maybe the clinics where somebody can really assess the child and make sure that they have been doing the right things (S4) |

| In (home country) the speech pathology she said using some spoon you hold his tongue behind the teeth down or up because he don't know the tongue, it's going up and down. And I try this once, maybe twice and now he know he saw something spoon or like that and he covered his mouth. Now he doesn't even try. (P1) | |

| Universal ECD services for early intervention | It was kids around them, because I haven't friends in this country the same age. That's why it was the best thing go to a playgroup. Because they need met another kids. (P1) |

| That's why maybe. So after coming back I used to take her to playgroup and the coordinator of the playgroup and she told me these services are available, you can take her to speech therapy you know. (P2) | |

Personal health practices

Help seeking behaviours

Service professionals gave examples of parents who were reluctant to hear a negative message about their child's development. Denial, shame, fear and guilt were perceived to drive this resistance. Mothers were described as being responsible for their child's development and perceived that they had ‘failed’ if a concern was raised. One GP felt that resistance was the parental response ‘70–80%’ of the time. However, another GP, some parents and early childhood professionals gave examples of parents seeking help when there was a developmental concern, despite feelings of guilt and self‐blame.

Process of care

Working in partnership

All services described the importance of working in partnership with families through building a trusting therapeutic relationship with parents. Professionals reported that a fluid, tentative, open‐ended way of interacting with families, a ‘soft entry’ or ‘fishing expedition’ seemed to work best. In this way, parents were helped to identify problems themselves if possible, or they could also be approached in a direct but sensitive way if they did not. There was a delicate balance in keeping resistant families engaged when there were developmental concerns so that their child had further assessment and early intervention in a timely manner.

Service quality

All participants described concerns in terms of the quality of some health and early childhood services in undertaking DS. It was reported that many GPs did not have the time to pick up on developmental issues, given their focus on general medical issues. However, there were also examples where GPs had detected developmental problems and referred on to early intervention.

Use of services

Sources of primary health care

GPs were seen as the first ‘port of call’ by parents and early childhood services when there was a developmental concern, as they were perceived as having the best access to a complicated health system. The CFHNs reported that following the six months of age check‐up, contact with families from CALD backgrounds was very irregular. Parents/carers also reported using CFHNs less frequently with subsequent children. A number of parents gave examples of conflicting advice given between health professionals from their ‘home’ country versus those in Australia.

Universal ECD services for early interven‐tion

Supported playgroups for the parents from CALD backgrounds were reported to be a key source of social support and affordable early intervention that could be further promoted amongst health professionals. There were many examples given of multicultural playgroup coordinators role modelling, informing and advocating for optimum ECD. Mothers whose children attended supported playgroups described them as being ‘life savers’. Drawbacks of playgroups noted were irregular attendance and their short hours.

Outcomes

See Box 7.

Box 7. Outcomes – Illustrative quotes.

| Outcome | Illustrative quotes from participants |

|---|---|

| Family satisfaction | I was still going. I was searching. I never gave up. Mm. It was just finding someone who believed me. And said there is a problem, finally admitting that there is something to be dealt with (P3) |

| That they feel they're being talked to like they are stupid, they don't know anything, they don't know their child, we know better, this is what we have to do. (S7) | |

| Missed opportunities | From speech point of view, I am aware expressive speech Is usually delayed if the child is raised in a bilingual environment .however…. I can confidently say that children whose parents are from non‐English background with mild or subtle development concerns tend to present much later. (S25) |

Family satisfaction

Many parents were satisfied with services; however, a number of parents described health professionals, in particular doctors, not taking their concerns about their children seriously. One mother described going from doctor to doctor including a hospital emergency department on three occasions before finding a doctor ‘many suburbs away’ who would believe her that there was ‘something wrong’ with her child's development (P3). Some professionals described issues with families being treated insensitively and poor professional communication.

Missed opportunities

Although there were instances of success in DS and early intervention described, the consensus was that children were ‘slipping through the net’ with their developmental problems undetected by the time they started school. Many services described ‘feeling impotent’ because children were not accessing high‐quality early intervention even after problems were detected due to waiting lists, affordability and parental resistance.

Discussion and recommendations

This qualitative study has explored key themes that parents/carers, health and early childhood professionals believe to impact on access to DS and early intervention for children from CALD backgrounds using the conceptual framework of BM. The demographic and psychosocial variables of English proficiency, socioeconomic status, family resources and ethnicity that were identified are well described in quantitative research.28, 30 What this study adds is further understanding of the process of access and the interaction of predisposing, enabling and need variables in this process on health behaviours and equity of access. In particular, it highlights the importance of family and service knowledge about ECD and DS, the impact of social isolation and community attitudes; how services are promoted, trained and resourced; and the clarity of referral pathways as key variables that play a role in a family's journey in accessing services. These merit further examination in qualitative and quantitative health service research.12, 21, 35

Professionals and parents were in agreement about most of the factors that they felt impacted on access to services; however, there was a key difference around perceptions of how parents and professionals respond when there is a developmental concern about a child. Many of the professionals described parents' denial and resistance, but many parents described trying to seek help and not being ‘heard’ by professionals. This highlights the importance of professionals working in partnership with families, advocacy, greater access to multicultural workers and interpreters, and professional grounding in communication skills, especially around having difficult conversations in a culturally appropriate manner.

Participant concerns about language delay in children from CALD backgrounds reflect international and Australian research on frequency and type of parental developmental concerns.36, 37 There was a general consensus that despite these concerns, children were not being identified and accessing early intervention in a timely manner. The lack of professional use of standardized tools (except CFHNs) for DS in our study may result in the underdetection of developmental problems such as language delay in CALD communities.11, 20 There were also many examples given of language delays and other significant developmental disorders in children from CALD backgrounds being missed due to professional and family belief that bilingualism, a child being exposed to more than one language, was responsible for late talking. Previous research shows that there is no evidence that children exposed to two languages reach language developmental milestones later than their monolingual counterparts in their first language although there may be qualitative differences in their speech sounds.20, 38 The false belief by professionals about the impact of bilingualism on language development in our study and lack of a standardized approach to DS highlights need for training professionals in culturally appropriate yet standardized approaches to DS.20

Our participants' experiences of complex referral pathways show a clear need for a coordinated referral pathway with strong GP–CFHN–early childhood collaboration. This will ensure high‐quality continuity of care in the preschool years for effective DS and early intervention. This is especially important as families from CALD backgrounds and early childhood professionals viewed GPs as the ‘first port of call’ when they had a developmental concern, and CFHNs were accessed infrequently after infancy and in families with more than one child.

Limitations

A systematic approach was used in sampling, data collection and analysis to enhance the reliability and validity of the study: checking of transcripts against tapes and notes taken, triangulation, and feedback, to ensure rigour. Although purposeful sampling was used to select a wide range of parents with different experiences, a potential limitation was that the majority of parents from CALD backgrounds were recruited through their connection to non‐government organizations which run multicultural playgroups. This meant that these parents may have been more in favour of these services. In addition, although we had parents from a wide range of CALD backgrounds, we did not have all key CALD groups represented. Five of our parents had one child with some sort of developmental problem as we wanted to understand the experience of parents who have been through the DS and early intervention ‘system’. We may have had different perceptions if our group of parents had less experience with developmental problems; however, within our current sample, we reached saturation and the negative case for all dominant themes.

The use of interpreters in three parents groups and the use of a playgroup for a group interview although strengths due to increasing the variety of parents we interviewed also pose limitations. We transcribed what the interpreters said verbatim not the parents. In the playgroup, we were not able to transcribe verbatim due to logistics, and some parents may have been less candid than they would have been in an individual interview.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the usefulness of conceptual models such as the Andersen Behavioural Model of Health Service Use in qualitatively exploring determinants of inequitable access to DS and early intervention. A number of service delivery and policy implications flow on from the findings. The study highlights the importance of increased community and family awareness through promotion of ECD, the need for training in DS for health and early childhood professionals; and better coordination of services, with simpler referral pathways to early intervention to prevent children from CALD backgrounds ‘slipping through the net’.

Funding

The project was funded by a grant from the Multicultural Health Unit at South East Sydney Local Health District.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Multicultural Health Unit of South East Sydney Local Health District, all the participants and the government and non government agencies that supported the project. In addition, we would like to thank Dr Alexandra Hendry, Professor Valsamma Eapen, Astrid Perry, Lisa Woodland, Milica Mihajlovic, Associate Professor Karen Zwi and Dr Meredith O'Connor for their input into the development and critique of this project.

References

- 1. Shonkoff JP. From neurons to neighborhoods: old and new challenges for developmental and behavioral pediatrics. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 2003; 24: 70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. AIHW . Headline indicators for children's health, development and wellbeing Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (ed.). Canberra, ACT: Australia, Cat. No. PHE 144, 2011: 1–162. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldfeld S, Mithen J, Barber L, O'Connor M, Sayers M, Brinkman S. The AEDI Language Diversity Study Report. Melbourne, Vic.: Centre for Community Child Health, The Royal Children's Hospital, Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson LM, Shinn C, Fullilove MT et al The effectiveness of early childhood development programs: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2003; 3 (Suppl.): 32–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J et al Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 2010; 125: e17–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Law J, Garrett Z, Nye C. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and language delay or disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McLaughlin MR. Speech and language delay in children. American Family Physician, 2011; 83: 1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. RCH, Centre for Community Child Health . Health Screening and Surveillance: A Critical Review of the Literature, National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra, ACT: Centre for Community Child Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9. AAP . Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics, 2006; 118: 405–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. King TM, Tandon SD, Macias MM et al Implementing developmental screening and referrals: lessons learned from a national project. Pediatrics, 2010; 125: 350–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woolfenden S, Short K, Blackmore R, Pennock R, Moore M. How do primary health‐care practitioners identify and manage communication impairments in preschool children? Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2013. DOI: 10.1071/PY12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winter P, Luddy S. Engaging families in the early childhood development story (MCEECDYA) Ministerial Council for Education, Early Childhood Development and Youth Affairs. Melbourne, Vic.: Early Childhood Services, Department of Education and Children's Services, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldfeld S, O'Connor M, Sayers M, Moore T, Oberklaid F. Prevalence and correlates of special health care needs in a population cohort of Australian children at school entry. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 2012; 33: 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fort HM, Harris E, Roland M. Access to primary health care: three challenges to equity. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2004; 10: 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murray SB, Skull SA. Hurdles to health: immigrant and refugee health care in Australia. Australian Health Review, 2005; 29: 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schyve P. Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: the joint commission perspective. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2007; 22: 360–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM, Abbott P et al Childhood disability in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: a literature review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2013; 12: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carmichael A, Williams HE. Use of health care services for an infant population in a poor socio‐economic status, multi‐ethnic municipality in Melbourne. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 1983; 19: 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oberklaid F, Baird G, Blair M, Melhuish E, Hall D. Children's health and development: approaches to early identification and intervention. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 2013; 98: 1008–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stow C, Dodd B. Providing an equitable service to bilingual children in the UK: a review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 2003; 38: 351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alexander KE, Brijnath B, Mazza D. Parents' decision making and access to preventive healthcare for young children: applying Andersen's Model. Health Expectations, 2013. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1995; 36: 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amin R, Shah NM, Becker S. Socio economic factors differentiating maternal and child health‐seeking behavior in rural Bangladesh: a cross‐sectional analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2010; 9 http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/9/1/9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halfon N, Inkelas M, Wood D. Nonfinancial barriers to care for children and youth. Annual Review of Public Health, 1995; 16: 447–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Habibov NFL. Modelling prenatal health care utilization in Tajikistan using a two‐stage approach: implications for policy and research. Health Policy and Planning, 2008; 23: 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fosu GB. Childhood morbidity and health services utilization: cross‐national comparisons of user‐related factors from DHS data. Social Science and Medicine, 1994; 38: 1209–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miller DC, Gelberg L, Kwan L et al Racial disparities in access to care for men in a public assistance program for prostate cancer. Journal of Community Health, 2008; 33: 318–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re‐revisiting Andersen's Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998‐2011. Psycho‐Social Medicine, 2012; 9: Doc11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P, Gelberg L. Determinants of regular source of care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Medical Care, 1997; 35: 814–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Research, 2000; 34: 1273–1302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. ABS . Australian Bureau of Statistics, Table Builder http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/tablebuilder accessed 4/2014.

- 32. Centre for Community Child Health and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research . A Snapshot of Early Childhood Development in Australia Australian Early Development Index (AEDI) National Report 2009. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenhalgh T, Taylor R. Papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). British Medical Journal, 1997; 315: 740–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, Version 10. QSR International Pty Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. COAG . Investing in the Early Years – A National Early Childhood Development Strategy. An initiative of the Councils of Australian Governments. Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Armstrong M, Goldfeld S. Good Beginnings for Young Children and Families: A Feasibility Study. Wodonga, Vic.: Health CfCC, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldfeld SR, Wright M, Oberklaid F. Parents, infants and health care: utilization of health services in the first 12 months of life. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2003; 39: 249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hambly H, Wren Y, McLeod S, Roulstone S. The influence of bilingualism on speech production: a systematic review. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 2013; 48: 1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]