Abstract

Background

Despite the availability of effective evidence‐based treatments for depression and anxiety, many ‘harder‐to‐reach’ social and patient groups experience difficulties accessing treatment. We developed a complex intervention, the AMP (Improving Access to Mental Health in Primary Care) programme, which combined community engagement (CE), tailored (individual and group) psychosocial interventions and primary care involvement.

Objectives

To develop and evaluate a model for community engagement component of the complex intervention. This paper focuses on the development of relationships between stakeholders, their engagement with the issue of access to mental health and with the programme through the CE model.

Design

Our evaluation draws on process data, qualitative interviews and focus groups, brought together through framework analysis to evaluate the issues and challenges encountered.

Setting & participants

A case study of the South Asian community project carried out in Longsight in Greater Manchester, United Kingdom.

Key findings

Complex problems require multiple local stakeholders to work in concert. Assets based approaches implicitly make demands on scarce time and resources. Community development approaches have many benefits, but perceptions of open‐ended investment are a barrier. The time‐limited nature of a CE intervention provides an impetus to ‘do it now’, allowing stakeholders to negotiate their investment over time and accommodating their wider commitments. Both tangible outcomes and recognition of process benefits were vital in maintaining involvement.

Conclusions

CE interventions can play a key role in improving accessibility and acceptability by engaging patients, the public and practitioners in research and in the local service ecology.

Keywords: action research, BME, community engagement, evaluation, interventions, mental health

Introduction

A wide range of interventions are effective in improving outcomes of common but disabling mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.1, 2 However, many groups with high levels of mental distress are disadvantaged because care is not available to them in the right place and time, or when they access it, their interaction with caregivers deters help seeking or diverts it into forms that do not address their needs. Drawing on a systematic reviews,3, 4 secondary analysis of existing data sets5, 6 and a conceptual review,7 we developed a complex intervention to improve access to mental health in primary care comprising three inter‐related components: community engagement (CE), promoting well‐being (comprising offer of a psychosocial therapeutic intervention) and improving quality of primary care provision.

This paper provides an overview of the rationale behind the CE model adopted to meet the aims of the wider Access to Mental Health in Primary Care (AMP) Programme8 and describes its implementation and evaluation.

Background: design for Community Engagement in the context of a complex intervention

Community engagement, which has been defined as:

‘building active and sustainable communities based on social justice, mutual respect, participation, equality, learning and cooperation. It involves changing power structures to remove the barriers that prevent people from participating in the issues that affect their lives’9

Has become a routine practice in many areas of health and public service provision and in some areas of research.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 The diverse aims and methods involved have led to a profusion of approaches, models and toolkits.

We undertook an extensive critical literature review of existing approaches. No single off‐the‐shelf approach met the needs of the programme. Accordingly, we drew pragmatically on a range of perspectives and techniques that have previously been used in CE for addressing health issues.17

Central to the intervention design was an understanding of access, treatment and recovery as a dynamic and often protracted set of processes and decisions, involving not only patients and health practitioners but also contingent on a wider range of community stakeholders and resources.18 Improving access for under‐served groups can involve addressing any of the barriers in the pathway: from people recognizing they may need help; to seeking, negotiating and engaging in treatment; to navigating successful treatment resolution and embedding effective self‐management.19 We determined that the nature, scale and impact of barriers and facilitators at the local level, as well as how they might best be approached, could only be understood by engaging actively with our target communities.

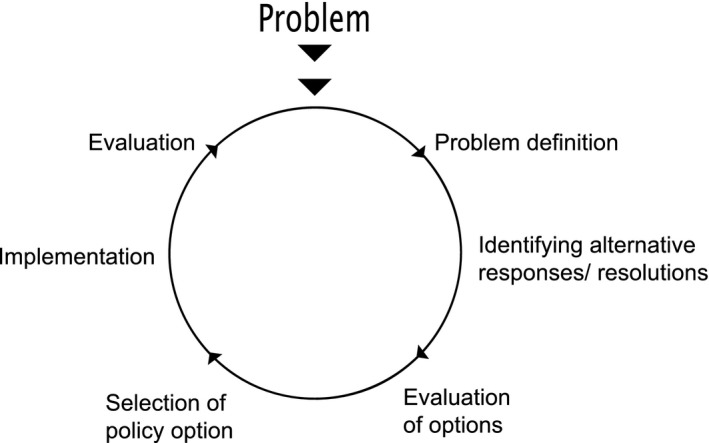

The CE model was conceived as an inductive community problem solving activity18 (Fig. 1). In drawing on the roots of action research, we found a common ground between well‐known approaches in health service improvement20 and community‐based participatory research.21 Aims were negotiated, augmented, refined and adapted through engagement as an integral part of the process. The role of the intervention team was to facilitate local action and local partnerships. It was envisaged that this approach would help stakeholders to continue beyond the intervention time frame by recognizing, utilizing and developing both local and wider resources.

Figure 1.

Common policy or problem‐solving cycle.

The approach emphasizes involving the community in reflecting on the problems and issues, and producing considered action at the local level in the relatively short time frame available. It allows for proactively building trust, key when working with under‐served communities with complex unmet mental health needs. The active collaborative participation involves local people and service providers in both negotiating and delivering on the agreed aims. Drawing on the wider traditions of action research, this can be seen as empowerment through action and delivery.22, 23, 24, 25

Methods

Aims

The CE component addressed four overarching programme aims (see Box 1).

Box 1. Aims of the Community Engagement intervention.

| Develop Knowledge | To develop our knowledge of the range of understandings and attitudes about mental health and wellbeing in the community |

| Networks and Partnerships | To develop local networks (required for the primary care training and the psychosocial intervention) to design and implement CE with these partners |

| Addressing Barriers to Access – 19 | To address stigma and the acceptability of seeking help and identify the practical barriers to engaging in treatment; to use this knowledge and these networks to address barriers to mental health‐care access and tailor health literacy approaches to improve awareness of mental health issues in the community, including, how, when and where to seek help |

| Embedding Gains and Agenda – Recursvity37 | To embed gains, foster relationships and raise the issue of improving access to mental health care, to impact on issues beyond the intervention time frame. |

The main focus of this paper is on the second aim: relationships between stakeholders, their engagement with the issue of access to mental health and with the programme through the CE model between 2010 and 2012.

Design of the community engagement model

Drawing on Lewin's18 ‘spirals’ of action research, our CE model involved four inductive components, implemented in sequence (see Box 2).

Box 2. Design of the Community Engagement model.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Information gathering | Consistent with aims 1 and 4 (see Box 1), identifies and engages with stakeholders for the following phases, which go on to address aims 2 and 3. The aims of information gathering were to:

|

| Community focus groups (CFGs) | Six‐monthly meeting of local stakeholders across the programme to provide feedback, priorities for action and strategic direction. The main roles of the CFG were to:

|

| Community champions | Champions were the day‐to‐day contact and face of the programme in the community, organizing and driving the activities identified in the CFG. |

| Community working groups (CWGs) | Monthly meeting of stakeholders working together to implement activities decided in CFG. |

Information gathering

Whilst our initial reviews provided key findings, knowledge and best practice in working with under‐served groups, they could not tell us about the specific issues in the intervention localities.

Information gathering was also the first step in building the trust and networks necessary for successful engagement. It involved the intervention team getting to know the local area, communities and stakeholders and understanding the range of issues related to mental health and access from local people's own perspectives.

We developed a research strategy drawing on the ethnographic tradition26 and incorporating recent methodological refinements.27 Information‐gathering lasted for about three months and involved three overlapping approaches:

Entry to the field: getting to know the localities and people and the experience of life in these communities. We used internet searches and site visits to identify local service providers and events where we could meet local people. We invited them to participate in ‘go‐along’ interviews, showing us around the local neighbourhood, telling us about local people, communities, the area and how they live their everyday lives.

Go‐Along interviews using snowball sampling28 from distinct start points located in the community (e.g. leaders, media, local business, education, police, health and social care providers, and within the voluntary sector). Accessing participants through local social networks allowed us to engage with people who would not be reached by sampling only from those in contact with formal services.

Mapping and collation of existing community data, using a snowball approach with starting points in primary care, public health, social care, voluntary sector, community media and local businesses.

These enabled development of:

Initial models of mental health understandings within the community

Key engagement messages

A database of contacts, projects and resources across health, social, voluntary and community sectors

Communications strategy – through identification of local community nodes, information points, media and key actors.

Our information gathering was built on ethnographic principles that the interviewee is the expert,26 and on the recognition that any knowledge we gained about the community would always be contingent, positional and incomplete.

Community champions

The Community Champion employed by the AMP programme in each locality was the primary day‐to‐day contact for the community and facilitated the community focus group (CFG) and community working group (CWG). These were part‐time appointments funded by the AMP programme. Senior members of the AMP research team supported each community champion.

Community focus groups

The Community focus groups (CFGs) were forums to negotiate the aims and agenda of the intervention with local people, agencies and wider stakeholders. The CFGs met every six months or so over a period of 2 years (see Box 3). We expected the CFGs to play an important role in negotiating different agendas between local service providers and to provide the strategic level buy‐in that was essential for many organisations if their workers were to dedicate time to participating in the working groups. It is important to emphasize that CFGs are not ‘focus groups’ as conventionally understood in the context of academic work. However, we found the term ‘Community Focus Group’ was the most useful and acceptable for communicating the broad intent of the group to a diverse range of stakeholders in way that all could understand and would be keen to engage with.

Box 3. Community Focus Group (CFG) participation.

| CFG 1 | CFG 2 | CFG 3 | CFG 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Third sector | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| Third sector (Bangladeshi) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Police | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Faith leaders | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GPs | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Practice managers | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Public health | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mental health counsellor (GPs) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Domestic violence counsellor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Teacher (secondary) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| AMP research team | 4 | 5 | 8 | 4 |

| Community champion | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 15 | 11 | 25 | 17 |

Membership of the CFGs was drawn from the contact list developed in the community mapping phase. They included primary care and wider health sector workers (health professionals and policy makers), members of voluntary or third sector organizations, faith leaders, community police, local business representatives and local councillors. Each site held four CFGs throughout the programme. Unlike conventional steering groups, the CFGs were participatory with members negotiating not only direction but also resources for action.

Community working groups

Whilst the focus of the CFGs was on strategic issues and direction, the focus of the CWG was on implementing the action plan formulated by the CFG. The CWG was intended to involve local workers, strategic partners and community members in dividing the tasks needed to deliver a project, using locally available people and skills. Meeting monthly, it was expected to provide a regular opportunity for members from different sectors to develop knowledge, relationships and partnerships, and hence to improve access to care through local services in the mid and longer term.

CFG attendees and a wider group suggested by them or identified during mapping were invited to attend, or nominate staff to attend the working group. We considered that splitting the ‘strategic’, agenda‐setting function of the CFG from the ‘operational’ function of the CWG might be useful in maintaining focus on the agreed actions and a sense of shared ownership of the group's activities by the wider community.

Intervention sites

The CE component was applied in two sites. We worked with South Asian people in Longsight in Manchester and with older people in Croxteth, Liverpool, both in the North West of England. We will focus here on Longsight as a case study as it also incorporated the Working Group element of the design.8 The Longsight community champion had lived in the area for a number of years. A British‐born Muslim with family in Pakistan, she had previous experience of working on cross‐cultural health issues in other localities. She worked substantially through the Community Working Group, many of whom became involved in the wider programme.

Evaluation

Evaluation in complex interventions involves attending not only to outcomes, but also to process evaluation. This details the background conditions that the ‘key ingredients’ require to operate and become embedded in the day‐to‐day routines and practices of the actors and stakeholders involved.29 The challenges of evaluating ‘action research’ type approaches in complex interventions are likewise well rehearsed.30, 31, 32 Illuminative evaluation has been used to approach the problems of evaluating interventions in a way which is meaningful to the range of institutional and public stakeholders typical in this kind of intervention.33 The first task in the CE evaluation was to understand the range of stakeholders – and for institutional stakeholders their operational background – during the intervention. There was a diverse range of process data available, from field notes of meetings to recordings of focus groups. These informed different aspects of the evaluation. The transcriptions of interviews carried out at the end of the programme were the primary source for the evaluation with reference made to other sources as necessary. The overall evaluation consisted of four related dimensions (see Box 4).

Box 4. Matrix for evaluation.

| Dimensions | Data |

|---|---|

| 1) Understanding stakeholders – Understanding the aims, needs and objectives of local strategic stakeholders and the degree to which the intervention addressed or advanced these agendas | Go‐along interviews, CFG and CWG field notes and recordings, Community Champion debriefing notes. Evaluation interviews. Wider process data (e.g. materials produced by CWG participants) |

| 2) CE model – Evaluating the efficacy of the model and processes of the CE approach we adopted | As above, + evaluation data from wider programme |

| 3) Population Impact – evaluating the potential for impact on the local population and patient body | Go‐along interviews. Focus groups conducted by community champion with local patient and community groups |

| 4) Evaluating the role of the CE intervention in the context of the wider programme | As above, + evaluation data from wider programme |

Analysis

Field notes, interview and focus group transcriptions from each phase were collected and coded by the originating interviewer using MAXQDA. Themes were developed inductively, in a grounded fashion34 with on‐going discussion across the research group, throughout the intervention. We then used an adaptation of framework analysis35, 36 to synthesize findings, develop our understandings of stakeholder groups and to understand their involvement and their perceptions of the interventions. The Framework approach involved developing a matrix (or table), of themes and sub themes on one axis, and individual informants, organized into stakeholder groups, on the other axis. The cells of the table hold direct quotes, allowing the research team to ‘eyeball’ the relationship between data and the organizing principles, or interpretations being applied. Development of the matrix, the themes and the groupings of stakeholders is an inductive process – being progressively refined until a configuration that best accommodates and explains the data is arrived at. The AMP team as a whole informed coding and matrix development at an interim analysis day. This involved researchers writing codes in three different coloured post‐it notes for grounded observations, insights from conceptual work and emerging themes. These post‐it notes were then arranged and re‐arranged into a draft matrix on an extended whiteboard to inform subsequent rounds of coding in MAXQDA. Framework had a number of advantages; firstly, as a procedure, it can be epistemologically neutral. The matrix can accommodate both data and concepts, allowing multidisciplinary teams with different perspectives and degrees of emersion in the data to work together. Secondly, different organizations of the themes and subthemes can be developed subsequently, allowing for orienting the matrix towards answering particular research questions. In our case, this involved synthesizing the grounded themes into frameworks based on the a priori evaluation aims and questions (Box 5); this was carried out by JL and HB prior to review by the rest of the team. The resulting matrixes demonstrated that the interpretations being brought to bear were supported by the data and informed the structure and content of the results presented below.

Box 5. Community Focus Group (CFG) priorities.

| Priorities identified for action | Action by CWG | |

|---|---|---|

| CFG1 March 2010 | Domestic violence, shame and honour, raising awareness, all generations |

Output 1 – Mental Health Calendar. produced and distributed 3000 mental health calendars tailored information and contacts in Urdu, English and Bengali. Output 2 – Facebook (and Twitter) a mechanism to share up to date information on changes in local services, events and resources, members could update their own information. A repository for mental health materials in South Asian languages. Output 3 – ‘Relaxation’ CDs in Urdu, English and Bengali to provide basic relief whilst waiting for treatment. |

| CFG2 September 2010 | Operational issues, timetabling, priorities | |

| CFG3 June 2011 | Communication and networking. Waiting times and language difficulties | |

| CFG4 June 2012 | Future of the group and agenda post intervention |

Results

The results below describe how the aims of the intervention were met through information gathering, building the CFG, negotiating aims and agendas, initiating action through the CWG and subsequent rounds of action and reflection. We draw on process data from across the intervention: indicative quotes and field notes are provided as appropriate to illustrate the themes emerging from the analysis.

Developing local knowledge

Longsight is an area close to Central Manchester in the UK, noted for its ethnically, linguistically and religiously diverse population. Census data suggests a population of around 15 500 (2011), although our preliminary work with local primary care providers suggested that up to double this figure were registered with local GPs.

During the information‐gathering phase (2–3 months), researchers immersed themselves in the local area, walking through the streets, shops, parks and market making field notes and taking photographs. These field notes provided an overview of local expertise and knowledge and gave us important insights into the motivations and needs of strategic stakeholders. The first stage focused on observing the activities and the ‘feel’ of the area:

‘I pass the Himmat Support Centre, which has a bouncy‐castle in the garden. There are several South Asian women standing near the front door. An Asian man in a wheelchair is being wheeled out of the gate, and a black man stands close to the gate, shuffling his feet; he appears to have learning difficulties and is talking to an Asian man that may have been his carer. The centre is busy and, on the basis of this afternoon's events, seems to be utilised by a varied cross section of the community.’

[Researcher notes]

The second stage involved understanding local activities through the eyes of the participants.

‘I sat and talked [informally] to … a member of the community mental health team, about his work in [Longsight] and … a football team for people with enduring mental health issues which he organises. He talked about his belief in the effectiveness of a community centre based approach to supporting people with mental health issues, and this was his motivation to become involved with [local church] and bring some of the CMHT's work to the centre.’

[Researcher notes]

Working through the contacts developed during the observation phase, go‐along interviews elicited more nuanced, personal or emotive understandings of the local area and people.

‘One woman said to me, “We used to have servants but now we are servants.” She was so ashamed that her son was a taxi driver when in Pakistan they had chauffeurs.’

[Researcher Notes]

The field notes from these exploratory site visits also enabled development of a database of local contacts and stakeholders. From this database, we identified potential candidates for the role of community champion and stakeholders to participate in the CFG.

The first community focus group provided a forum to feed back our findings, discuss them in the wider group and identify shared priorities for action. The agenda for each meeting tracked the problem‐solving cycle (see Fig. 1) and emerging priorities, and areas for action identified by the group are summarized below (see Box 5). Researchers used field notes and recordings to produce a summary of the discussions and action points for the CWG.

As Box 5 shows, the majority of agenda setting took place in the first CFG. However, issues and priorities were further developed over time. The first CFG highlighted that we had underestimated the role played by domestic violence and the fear of domestic violence. A local domestic violence expert was identified and recruited to the team.

Building networks and partnerships

A key challenge in multi‐agency working is negotiating common agendas between partners with different organisational structures, operational conditions, funding cycles and understandings of professional roles. Both strategic and operational staff can be required to formally or informally justify their investment of time (e.g. to line‐managers). The CFG provided a forum for negotiating values and trust as well as agendas and action plans. It also provided an arena for those working with patients and clients with depression and anxiety to discuss their experiences, issues and problems and to learn about other help available. We held CFGs at a number of different venues in the community to help members get to know other services.

Across all stakeholders, communication and time to communicate was considered a significant barrier to working together. This was exemplified in the first CFG. Whilst the third sector members were aware of one another, none of the primary care providers were aware of the local third sector group providing mental health drop in and counselling.

‘Most of the GPs are not aware of the services that are available within the community, so we don't get information about the services – only today… we didn't know that there's a local community centre which provides all these services.’

GP

The third sector representatives discussed how they regularly sent materials to GP surgeries but, despite a number of attempts, they had not been able to make contact.

‘We've done a lot of work trying to get GPs to know what we do in the local area – and there was a lot of knocking on doors a couple of years ago’

Community Group Manager

A primary care manager explained the barriers to establishing communications in the context of the daily demands on a busy GP surgery,

‘On any given day I'll get twenty or thirty emails and then I'll get sort of three four types of leaflets in my in‐tray “please put these in your surgery” I'll get five or six posters, most of them are in English. And I'll phone the head office to find out if they do it in Bengali or do it in whatever and then it's finding the space to put them.’

Primary Care Practice Manager

The practice manager went on to emphasize that materials must be highly accessible, not only in terms of patients’ literacy and language needs, but that communications and technologies must take account of the operational contexts of GP consultations:

‘Some things are better now – the diabetes ones you can get everything on the internet in a leaflet form [language]. So if the patient's in the consultation room the doctor can just print one off and give it to them.’

Primary Care Practice Manager

‘We have leaflets on audio file in about thirty different languages so even if they can't read…’

Community Centre Manager

‘It has to be really accessible – because the Doctors have ten minute appointment slots – so it'll take ten minutes for the person to come out with something and then if the internet's down or whatever it's not reasonable to expect them to get all the things off the computer in peak time’

Primary Care Practice Manager

Changes in service provision and personnel were also perceived as a barrier. Differences in organizational culture appeared to play a part. For instance, whilst most third sector providers had an online presence and used Twitter and Facebook to find out about new services, many NHS terminals specifically removed access to Facebook. GPs preferred to access services and referrals through their practice computer systems.

Addressing barriers to access – candidacy

Applied in the context of access for vulnerable groups, ‘candidacy’19 (Box 5) describes a person's readiness to identify their problems, or those of others, as legitimate reasons for health care or treatment. The lack of perceptions of a right, or need for care by patients, family members, or clinicians was identified as an important personal, social and cultural barrier to access.7

The CWG met for the first time in July 2010. Led by the community champion, the group included local service providers, public health, a community police officer, a local Imam and the practice manager of one of the practices involved in the study, joined by members of the research team. The first meetings revealed the group had a high level of cultural knowledge and specific experience but few had routinely worked together in the past. Turnout, enthusiasm and commitment remained high throughout the process and members took the initiative in inviting along people from other groups and services.

Working together in the CWG on a multi‐lingual mental health calendar (see Box 5) was reported to have benefited a range of stakeholders, both because of its content and the development of local networks associated with its creation. The calendar fostered awareness of candidacy and identification with the health message about accessing care as the calendar was passed to clients, between members of the public and between health professionals:

‘It's done awareness raising, it's kind of brought it out in the open, yeah, um it's given them a tool to go off, it's given them an arena for discussion about it because it kind of mentions quotes from the Koran as well so it's kind of got them to reflect that you know there is some of these or something that talks about mental health so it is something that happens in that community… I think when I spoke to people even though some there are some people that will not access our services because … they're a hard to reach community – but there've been people that have said oh I've passed my calendar onto somebody who needed it so indirectly that work was done basically yeah.’

CWG Member

There was a recognition that aspects of the cultural tailoring and adaptation of the calendar for the South Asian population would be difficult to achieve in conventional settings.

‘I have to admit I was a bit I didn't like the bit about black magic the way it was described but I understood where people were coming from and sometimes you've just got to go OK well you're speaking from the community's experience so that's the way we need to go.’

CWG Member

An issue emphasized in CFG3 was the long waiting times for counselling and mental health services in South Asian languages, particularly Bangla. Many members of the group were looking for resources and materials that could help patients and clients both whilst they were waiting for treatment and to provide more appropriate and accessible resources for them. After reviewing all the materials they could access, they found little that they considered fully appropriate and freely available. Members of the group have been working together on the content of an audio compact disc that they plan to make freely available to download from the Facebook group.1

Embedding gains and raising the agenda – recursivity

Recursivity37 (see Box 1) describes the cyclical impact of people attempting to access care and inadequate, or unacceptable care being offered. Over time, this can lead to a perception in particular communities that care is either not appropriate to them, or not available to them. Related to candidacy, progress in addressing recursivity involves social and cultural change over time.7 Personal presentation by a person the community identified with was recognized as an important mode of delivery in an avowedly oral culture. The Community Champion appeared on Asian Sound Radio to promote the calendar and the work of the group. The 2011 mental health calendar was launched in late December 2010. It was distributed through local GP practices, third sector partners (non‐governmental organisations) including mental health groups, Pakistani and Bangladeshi community groups and mosques, and later refreshed and updated for 2012. During 2011–12, over 3000 calendars were distributed in a population that according to census data has 5502 Pakistani and 1761 Bengali residents (although we suspect this is an underestimate). The calendar was popular with the public, health‐care providers, teachers and others working in the community.

Overall, respondents appeared to consider the work of the CFGs and CWG to be important and valuable. The facilitatory work and commitment of the community champion in maintaining contact through emails and phone calls appeared to be particularly important in this regard.

Whilst all stakeholders valued working together and building therapeutic partnerships across statutory and third sectors, routine activities did not provide a framework to move this up their list of competing priorities. Many, particularly in the third sector, had attempted, with limited success, to build these relationships in the past. The opportunity to work together on a common project helped in making new contacts, getting to know existing contacts better and developing trust.

Discussion

Problematic communication has been the biggest single issue identified through the community engagement intervention. Our overriding philosophy was to bring novel technology and innovative approaches to solve communication problems whilst emphasizing the importance of face‐to‐face interaction and in‐depth engagement with the community and community agencies.

Our initial mapping suggested a disparity between needs and routine service provision had perhaps played a role in fostering a vibrant ecology of third sector organisations. This was accompanied by a high level of flexibility and accommodation on the part of local service providers who frequently went beyond what might normally be expected of their roles to meet the needs of local people. The utility of our CE model was enhanced by its configuration as a discrete intervention with a phased approach and focused agenda. Our evaluation suggested that each component of the model had to be in place to effectively manage the multiple agendas and multiple stakeholders.

The phased approach gradually built trust with local people and organizations. This was evident, for example, in the increasing number and type of stakeholders attending the CFGs. Establishing a focused agenda, achievable within the limited timeframe of the AMP intervention, appeared to be valuable.

The limited time‐frame may have paradoxically proved advantageous. Both information gathering and evaluation highlighted respondents who had previous experiences of CE as an extended ‘talking shop’ that did not result in tangible action. In working together to produce specific outputs, our groups gained confidence in their ability to act, and in each other. The opportunity to engage in the programme, within a specific time frame and working on defined projects, appeared to offer an impetus to ‘do it now’.

Relevance to the published literature

The CE element of the AMP programme was tailored specifically to meet the needs of CE in a health intervention context. A key difference between our approach and more longstanding Community Development38, 39 approaches was a need to deliver tangible outcomes, on a controlled range of issues at the local level, within the intervention timeframe.24 Meeting the aims of the programme relied upon identifying and working towards solutions for the issues identified with community stakeholders.

The CE approach needs to give communities a sense of collective ownership of the interventions by involving them in both the design and delivery. Social capital theories have suggested that whilst deprived areas have higher levels of ‘bonding capital’ they are less likely to leverage ‘bridging capital’ to bring external resources to bear on addressing local problems.40 Asset‐Based approaches41 emphasize recognizing, utilizing and developing a community's assets and resources but recognize the need to draw on and bring in external skills and resources in a way that respects communities ownership of interventions. Many aspects of the programme are consistent with the vision of contemporary assets‐based approaches. The CE intervention approach and the wider programme methods drew on the inductive cycles of the action research tradition.18 The wide‐ranging influence of Lewin's action research in both working with the community and in contemporary management theory provided a practical and conceptual bridge which could accommodate the differential natures of NGOs, smaller community organizations and large state providers.

A recent systematic review42 highlights the difficulties of building a coherent evidence base for the effectiveness of community engagement in health inequalities. In particular, the authors note the limited evidence for outcomes based on theories of empowerment and insufficient resources allocated to rigorous process evaluation. However, we would argue this rests on the somewhat binary categorization of outcomes as systems focused or empowerment focused. The accounts related in the case studies here focus attention on the underlying complexities of valuation frames of individual participants and stakeholders. Many stakeholders are themselves operating simultaneously in both systems and community empowerment paradigms and bring multiple frames to valuations of both their wider roles and intervention outcomes.

Our findings also suggest that if we examine contemporary community engagement practices in the light of the more longstanding traditions of action research, we are reminded that dichotomization of systems and community are not so fundamentally distinct. Traditional action research emphasizes involving all stakeholders in problem definition, evaluating and implementing solutions and evaluating progress to inform future decision‐making. This division between action and reflection is mirrored organizationally in the division of labour between operational implementation and strategic decision‐making. This fundamental principle of discrete phases of action and reflection addresses some of the barriers and inertia faced by individual actors engaging with complex problems.

By providing a common arena for negotiating understandings of purpose, progress and roles, it empowers stakeholders to take collective action by trusting that mechanisms are in place. Communication, trust and knowledge translation between stakeholders both strategically and operationally is paramount. Whilst there has been much progress in theory and practice of community engagement, we consider these rudiments remain fundamental to understanding the mechanics of community projects. These principles of inductive problem‐solving outlined by Lewin formalized a process that so permeates our culture that it is in many ways ‘hidden in plain sight’. Process analysis allows us to take a more refined view of the finessing of these basic ingredients required to implement the model a given context.

Limitations and strengths

In Longsight, the separation of priority setting and strategic issues in the CFG, and working on joint action on the resulting agenda through the CWG, appeared important in enabling effective working. However, whilst we thought we had explained this aspect of the CE model to stakeholders and participants on numerous occasions, there appeared limited understanding of its intended operation when discussed in evaluation interviews. The division of strategic and operational aspects between the CFG and CWG was often unclear to those who were not routinely dealing with strategic issues. It seems that stakeholders needed to trust that this did work, without necessarily having an interest in why or how it worked. In retrospect, detailing the CE model and collecting all relevant materials together on a project internet site may have provided a more accessible source of information than printed, distributed materials.

Conclusions

Community engagement can be highly effective in a time‐limited intervention as part of a complex intervention. CE brings ownership to stakeholders, can embed gains at the local level and allows for tailoring of other aspects of the intervention to local needs.

In deprived communities with limited ability to engage with and navigate services effectively, and where wider and more longstanding development initiatives are in place, we would argue that CE has become essential in coordinating interventions and engaging patients, the public and local practitioners in both collaborative delivery of mental health care and participation in mental health research.

Some key mechanisms worth considering by those undertaking future CE work in health access are summarized below:

CE was essential in developing a fuller understanding of the issues contributing to poor access and how existing health systems, materials or communications failed to meet the needs of communities

Engaging communities and professionals to work together produced materials that the wider community engaged with, understood and identified with

The communities’ engagement and identification with these materials then enabled diffusion through extended social networks, empowering community members to act as knowledge brokers

The validity of the materials was nevertheless underpinned by distribution through more established knowledge brokers such as GP surgeries, Mosques and Community Centres

The wide dissemination of these tangible products provided essential evidence of the capacity for progress and contributed to perceptions of the success of the intervention for both participants and the wider community

Community members and local professionals working together fostered a sense of ownership of the interventions, developed and strengthened networks and empowered the community by demonstrating their capacity to act together to address local issues

A challenge for future research will be to address the methods of evaluation and implementation appropriate to evidence‐based medicine whilst maintaining the characteristic flexibility, community participation and ownership of such interventions.

Acknowledgements

This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (http://www.nihr.ac.uk/funding/programme-grants-for-applied-research.htm). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Note

References

- 1. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Common mental health disorders—identification and pathways to care: NICE clinical guideline [Internet]. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011. Report No.: 123. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123, accessed 11 February 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Common Mental Health Disorders: Evidence Update March 2013 [Internet]. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2013. Available at: https://arms.evidence.nhs.uk/resources/hub/943108/attachment, accessed 25 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lamb J, Bower P, Rogers A, Dowrick C, Gask L. Access to mental health in primary care: a qualitative meta‐synthesis of evidence from the experience of people from “hard to reach” groups. Health, 2012; 16: 76–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dowrick C, Gask L, Edwards S et al Researching the mental health needs of hard‐to‐reach groups: managing multiple sources of evidence. BMC Health Services Research, 2009; 9: 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chew‐Graham C, Kovandzic M, Gask L et al Why may older people with depression not present to primary care? Messages from secondary analysis of qualitative data. Health and Social Care in the Community, 2011; 20: 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kovandžić M, Chew‐Graham C, Reeve J et al Access to primary mental health care for hard‐to‐reach groups: from ‘silent suffering’ to ‘making it work’. Social Science and Medicine, 2011; 72: 763–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gask L, Bower P, Lamb J et al Improving access to psychosocial interventions for common mental health problems in the United Kingdom: narrative review and development of a conceptual model for complex interventions. BMC Health Services Research, 2012; 12: 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dowrick C, Chew‐Graham C, Lovell K et al Report to the National Institute for Health Research on an R&D programme to increase equity of access to high quality mental health servivces in primary care (RP‐PG‐0606‐1071) [Internet], 2013. Available at: http://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/pgfar/volume-1/issue-2, accessed 31 October 2013.

- 9. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Community engagement to improve health [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2008: 1–91. Report No. 9. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph009, accessed 24 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blake G, Diamond J, Foot J et al Community Engagement and Community Cohesion. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen EK, Reid MC, Parker SJ, Pillemer K. Tailoring evidence‐based interventions for new populations: a method for program adaptation through community engagement. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 2013; 36: 73–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chung B, Jones L, Dixon EL, Miranda J, Wells K, Community Partners in Care Steering Council . Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning community partners in care. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 2010; 21: 780–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health . Engaging and responding to communities. A Brief Guide to Local Involvement Networks [Internet]. Department of Health, 2010. Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/links/healthcareproviders/Documents/Engaging_and_responding_to_communities_LINks_guide_for_professionals.pdf, accessed 28 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Michener J, Yaggy S, Lyn M et al Improving the health of the community: Duke's experience with community engagement. Academic Medicine, 2008; 83: 408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rogers B, Robinson E. The Benefits of Community Engagement: A Review of the Evidence. London: Home Office, 2004: 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Swainson K, Summerbell C. The effectiveness of community engagement approaches and methods for health promotion interventions [Internet]. National Institute of Clinical Excellence, 2008: 1–226. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph9/resources/community-engagement-health-promotion-effectiveness-review-phase-32, accessed 29 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Downe S, Mckeown M, Johnson E, Koloczek L, Grunwald A, Malihi‐Shoja L. The UCLan community engagement and service user support (Comensus) project: valuing authenticity, making space for emergence. Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 392–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lewin K. Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 1946; 2: 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Woods MD, Kirk D, Agarwal S et al Vulnerable groups and access to health care: a critical interpretive review [Internet]. National Coordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organization R & D (NCCSDO), 2005. Available at: http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/81292/ES-08-1210-025.pdf, accessed 25 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee SYD. Review: conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 2008; 65: 379–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Las Nueces D, Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, Hicks LS. A systematic review of community‐based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Services Research, 2012; 47 (3 Pt 2): 1363–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braithwaite RL, Bianchi C, Taylor SE. Ethnographic approach to community organization and health empowerment. Health Education & Behavior, 1994; 21: 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salzer M. Consumer empowerment in mental health organizations: concept, benefits, and impediments. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 1997; 24: 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wells KB, Miranda J, Bruce ML, Alegria M, Wallerstein N. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 2004; 161: 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yoo S, Weed N, Lempa M, Mbondo M, Shada R, Goodman R. Collaborative community empowerment: an illustration of a six‐step process. Health Promotion Practice, 2004; 5: 256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gold RL. The Ethnographic Method in Sociology. Qualitative Inquiry: QI, 1997; 3: 388–402. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carpiano RM. Come take a walk with me: the “go‐along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well‐being. Health & Place, 2009; 15: 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Biernacki P, Waldorf D. Snowball sampling: problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research [Internet], 1981; 10: 141–163. Available at: http://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=146745, accessed 22 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. May C, Mair F, Dowrick C, Finch T. Process evaluation for complex interventions in primary care: understanding trials using the normalization process model. BMC Family Practice, 2007; 8: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J et al Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ, 2007; 334: 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Craig P, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: reflections on the 2008 MRC guidance. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2012; 50: 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanson‐Fisher R, Redman S, Hancock L et al Developing methodologies for evaluating community‐wide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 1996; 11: 227. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Russell J, Greenhalgh T, Boynton P, Rigby M. Soft networks for bridging the gap between research and practice: illuminative evaluation of CHAIN. BMJ, 2004; 328: 1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Glaser B. Conceptualization: on theory and theorizing using grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2002; 1: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research In: Brymon A, Burgess RG. (eds) Analysing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge, 1994: 174–194. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation [Internet]. National Centre for Social Research. London: Cabinet Office, 2003. Available at: http://www.civilservice.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/a_quality_framework_tcm6-38740.pdf, accessed 31 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rogers A, Kennedy A, Nelson E, Robinson A. Uncovering the limits of patient‐centeredness: implementing a self‐management trial for chronic illness. Qualitative Health Research, 2005; 15: 224–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seebohm P, Gilchrist A. Connect and Include [Internet]. London: National Social Inclusion Programme, 2008: 74 Available at: http://cdf.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Connect_and_Include.pdf, accessed 12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seebohm P, Henderson P, Munn‐Giddings C, Thomas P, Yasmeen S. Together We will Change: Community Development, Mental Health and Diversity [Internet]. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2005. Available at: http://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/pdfs/Together_we_will_change_report.pdf, accessed 4 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Altschuler A, Somkin C, Adler N. Local services and amenities, neighborhood social capital, and health. Social Science and Medicine, 2004; 59: 1219–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burkett I. Appreciating assets: a new report from the International Association for Community Development (IACD). Community Development Journal, 2011; 46: 573–578. [Google Scholar]

- 42. O'Mara‐Eves A, Brunton G, Mcdaid D et al Community Engagement to Reduce Inequalities in Health: A Systematic Review, Meta‐analysis and Economic Analysis. London: National Institute for Health Research, 2013: 1–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]