Abstract

Background

Although it is widely recognized that children are willing, capable and legally entitled to be active participants in their health care, parents are generally invited to evaluate paediatric hospital care and services rather than children themselves. This is problematic because parents cannot serve as the only spokespersons for the perspectives and experiences of children.

Objective

To investigate children's experiences with and perspectives on the quality of hospital care and services in the Netherlands, and how they think care and services could be improved.

Design

A qualitative study incorporating different participatory data collection methods, including photovoice and children writing a letter to the chief executive of the hospital.

Setting

Paediatric departments of eight hospitals in the Netherlands (two teaching and six regional).

Participants

Children and adolescents (n = 63) with either acute or chronic disorders, aged between 6 and 18 years.

Results

The research results provide insights into children's health and social well‐being in hospitals. Important aspects of health, like being able to sleep well and nutrition that fits children's preferences, are structurally being neglected.

Conclusion

The participatory approach brought children's ideas ‘alive’ and generated concrete areas for improvement that stimulated hospitals to take action. This demonstrates that participatory methods are not merely tools to gather children's views but can serve as vehicles for creating health‐care services that more closely meet children's own needs and wishes.

Keywords: children, hospitalization, Netherlands, paediatric health care, participatory research, patient participation, photovoice, young people

Introduction

Children and adolescents are significant users of health‐care services, and it is increasingly accepted that they are not only objects of care but knowledgeable social actors who have their own perspectives on issues that relate to them, including health care.1, 2, 3, 4, 5

These changing views of children have led to international reforms in health policies, guidelines and legislation to support or even obligate the involvement of young people in decisions about their health care. For example, in September 2011, the Council of Europe adopted the Guidelines on Child‐Friendly Health‐Care. These Guidelines aim to integrate already existing international conventions for children's rights with respect to health and health care, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), into a practical framework that promotes the delivery of child‐oriented health care in the Council of Europe member states. Participation is one of the five main principles of these Guidelines and needs to be applied in individual medical decision making and in the assessment, planning and improvement of health‐care services.6

The Netherlands is one of the pioneer countries in recognizing the rights of minors to participate in treatment decision making. The Dutch Medical Treatment Act (WGBO;1995) states that young people aged 16 or over have the right to make their own treatment decisions, and those between 12 and 15 years are entitled to take decisions with their parents. The Dutch legal system, however, does not require children's participation in health care at the collective level, as service‐users or in policy‐making processes. Consistent with daily hospital practice in the Netherlands7, 8, 9 and elsewhere,10, 11 children and young people are rarely given opportunities to provide feedback on their experience of hospital care and services. Children's willingness12, 13, 14 and capability15, 16, 17, 18 to have a say in health‐care services and the value of their perspectives for improving child‐oriented care19, 20 have repeatedly been demonstrated, but the opinions of parents still generally form the basis for measuring the quality of paediatric hospital care.21, 22, 23, 24 This is problematic because the views of parents, although important, do not represent those of children, and thus, parents alone cannot serve as spokespersons for their children.25, 26, 27

The current paper describes a multihospital study that was carried out in eight Dutch hospitals. It is the first comprehensive study of children's and young people's experiences with and perspectives on the quality of paediatric hospital care and services in the Netherlands. It contributes to a growing body of knowledge about how children can play an active role in creating health‐care practices that better suit their own needs. Furthermore, it provides evidence about the potential of participatory research techniques to invoke change in health‐care settings. In this paper, we use the term children when referring to our study population (6–18 years old). We distinguish between particular age groups when relevant.

Methods

Design

We used a qualitative study design incorporating a wide range of participatory data collection methods.28 Photovoice and ‘letter to the chief executive’ were open to all ages. With adolescents (13–18), online and face‐to‐face interviews were also used. These methods were chosen because they allow the children to tell their own story instead of making them the object of the researcher's inquiry.29, 30, 31

Setting

Both in‐ and outpatient paediatric departments of eight Dutch hospitals participated in the study. Two of the hospitals are teaching hospitals with an associated paediatric hospital. The others are smaller, regional hospitals. In six hospitals, one of the four methods was used, and in the other hospitals, two or three methods were used. The distribution of the methods between the different hospitals depended on their preferences, target group and capacity to facilitate the data collection activities. When more than one method was available, children could choose which method they preferred; only one method per child was used.

Participants

Some 63 children with either acute or chronic conditions, aged 6–18 years, participated in the study (Table 1) with an average age of 13 years. The vast majority of children were recruited from inpatient departments (n = 58).

Table 1.

Number of participants for each of the methods used

| Method | No. of hospitals involved | Girls | Boys | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photovoice | 3 | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Letter to the chief executive | 1 | 10 | 13 | 23 |

| Online interviews | 3 | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Face‐to‐face interviews | 3 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| TOTAL | 32 | 31 | 63 |

Procedures

Children were invited to participate in the study by hospital play specialists who provided them and their parents with a letter explaining the aims and procedures of the study. We considered that hospital play specialists were the right persons to decide which children might be interested and able to participate. If children agreed to participate, they were approached by one of the researchers from the national patient organization (Zorgbelang) who planned and carried out the data collection activities. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Photovoice

Only children who stayed in hospital for 3 days or more could be involved in the photovoice activities because they needed to have enough time to take photographs. In addition, a stay of 3 days or more gave them more experiences on which to draw. Children received an introduction box containing a camera, an information and instruction letter for themselves and their parents, a consent form, and a notebook and pen. Children were asked to make a total of 10–15 photographs, capturing things and places they liked and did not like. Children were given up to 1 week to take the photographs, depending on the length of their stay. After this, the photographs were printed. Then, children incorporated their photographs with texts, explaining the meaning behind the photographs in either a scrapbook or collage. These were used to present the results to the hospital management but also formed the basis for face‐to‐face discussion of the photographs with children, either individually or within a group. During these photo‐elicitation interviews, the interviewer asked short questions, such as: What is this? What is happening here? Why did you make this picture? The interviews were generally conducted at a quiet room in the hospital shortly after making the photographs. In two instances, the interview was done at home because the child had already been discharged. As an acknowledgement of their efforts, children received copies of their photographs after the interview.

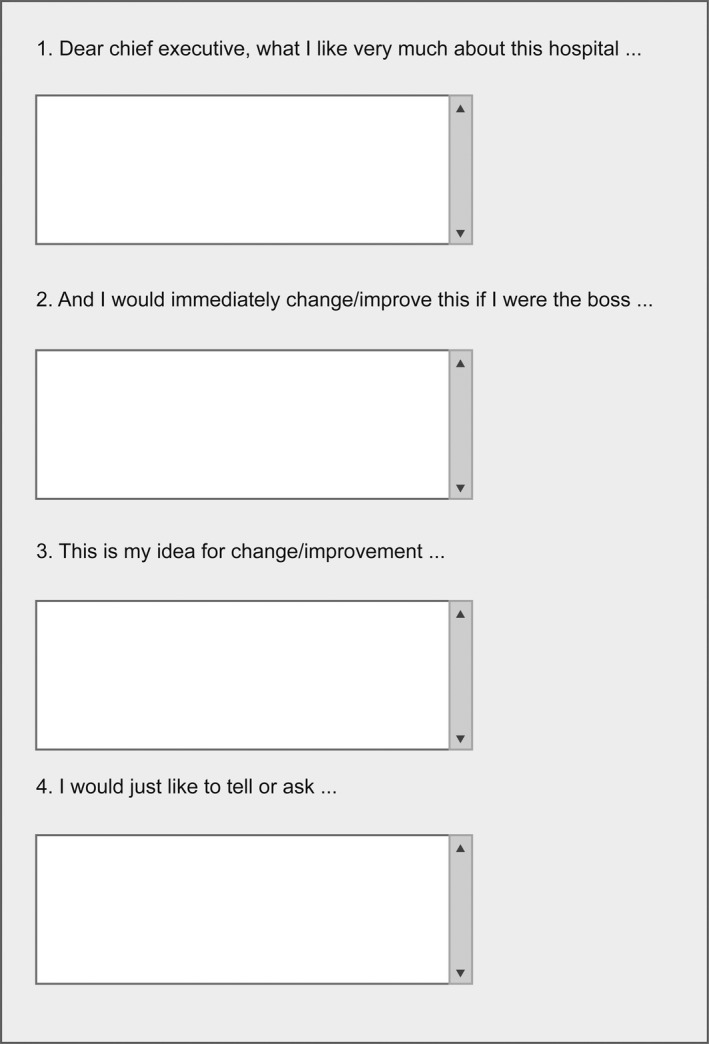

Letter to the chief executive

Children were invited to write their letter through a specially designed format (Fig. 1), available through a link on the website of the hospital. In this hospital, all children have access to an infotainment system above their bed on which they could fill in the format at a moment that suited them. The letters were automatically saved and copied into a Excel file for analysis.

Figure 1.

Format ‘letter to the chief executive’.

Online interviews using Facebook or MSN Messenger

Interview appointments were made on a day and time that suited the participants. More than half of the interviews (n = 7) were conducted while children were still hospitalized, and these participants were given a laptop or iPad, so they could participate in the interview from their bed. In the other six cases, adolescents participated at home shortly after their discharge from the hospital using their own computer. The interviews were semi‐structured; the interviewer opened with some general questions, such as: What was it like to be admitted at the hospital? What went well and what not? If you were the boss of the hospital what would you change? The interviewer asked probing questions to search for depth in the children's stories. The interviews lasted about 30 min. Afterwards, the transcription of the conversation was copied and saved in a Word file after which the chat history was deleted to guarantee the privacy of the participants.

Face‐to‐face interviews using pre‐formulated statements

Children were asked on the spot if they wanted to participate. Children that agreed participated from their own room and were given a box with pre‐formulated statements (Table 2) that served as starting points for the conversation. Young people were asked to pick statements from the box and to discuss their associations and experiences with them. Moreover, participants were explicitly invited to bring up their own topics of discussion. In this way, the dialogue between child and researcher was encouraged without the researcher being dominant.

Table 2.

Examples of pre‐formulated statements

| There is too little to do in the hospital for young people my age. |

| Everyone should have a computer in their room with access to the Internet. |

| When I need someone in the hospital, they should always come right away. |

| I do not like that I have to share a room with children that are much younger or much older than me. |

| I am not afraid to ask the nurse or doctor a question. |

| It is always asked what I would like and that is being listened to. |

| They ask my parents more questions and explain more to them than to me. |

Ethics

As the research project does not fall under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, official ethical approval was not needed. All participants and their parents received verbal and written information about the project and provided written consent. Verbal consent was obtained from children prior to audio recording of interviews. The children were informed that the information provided would not be linked to their individual identities, that participation was voluntary and that withdrawal was possible at any time. For example, two children that had agreed to participate in a face‐to‐face interview withdrew because they were too ill or too tired on the day of the interview. Four children that participated in the photography activities withdrew from the photo‐elicitation interview after they had been discharged because they decided they did not want to be interviewed. The research team was concerned not to overburden the children. Researchers drew the interviews to a halt if children's verbal and physical expressions indicated that they needed some rest.

Data management and analysis

All data were stored digitally. The written data were analysed together using qualitative content analysis.32, 33 All transcripts were read in their entirety and coded for recurring themes. The codes were then sorted into more abstract (sub) categories. The derived categories were discussed and revised with the project team. As photographs used in photo‐elicitation are not intended to stand alone,34 the photographs were not analysed in detail themselves. Instead, they were used to generate dialogue on how children give meaning to their hospital experiences.

Results

The aim of this study was to explore comprehensively children's experiences with and perspectives on the quality of paediatric hospital care and how this can be improved. By analysing children's positive and negative experiences, five themes were identified: (i) attitudes of health‐care professionals, (ii) communication with staff, (iii) contact with peers and family, (iv) treatment procedures and (v) hospital environment and facilities.

Attitudes of health‐care professionals

Children emphasized that doctors, nurses and other hospital staff needed to have sufficient time and attention for patients and should be willing to help the patient and to answer questions. They also appreciated personal qualities of staff members, such as sociability, kindness and amiability:

I believe the nurses are doing a good job. They are kind to me and they are patient.

(6‐year‐old girl)

These positive experiences, as well as the less positive ones, emphasize the importance of pleasant, open interaction between patients and their care givers. According to children, hastiness and a lack of time among nursing staff, which is unfortunately not uncommon due to the high workload in health care, does not contribute to such interaction:

Some are very brusque […] One of them just tosses down the medicines and then walks away quickly. They could at least say something.

(14‐year‐old girl)

Communication with staff

Children emphasized the importance of effective communication, including being well‐informed, health‐care professionals speaking directly to them, consultation between hospital staff, and being listened to.

Accessible and adequate information

Children frequently stressed the importance of being clearly informed about the treatment, planning and procedures. Children also wanted to receive information about details that adults may consider not interesting or too complex for children, such as the type of medication they are receiving.

Well‐informed children are generally very satisfied and describe examples of situations in which they were well prepared and knew what to expect:

They explained everything very well, before I underwent surgery. I was well informed about what they were planning to do and why. I appreciate that very much.

(14‐year‐old girl)

Poorly informed children, on the other hand, express feelings of discomfort or even anxiety. They articulate a strong desire for appropriate information about the timing, purpose and procedures of medical interventions and the opportunity to ask questions:

There is not enough time to ask questions. I was not well prepared for the surgery. I did not know how long I had to stay here [the hospital], whether or not I could go outside, whether or not I was allowed to take a shower. I did not have the opportunity to ask those things beforehand. I had to ask all those things yesterday, at the very last moment, in the operating room.

(18‐year‐old girl)

Direct communication with staff

Children, and in particular adolescents, highly appreciate being directly approached by health professionals, rather than through their parents:

You are kept informed about everything, which is great. They ask you questions, they ask me and my parents. Both, really. That is great. Everything is always clear to me and that is what is most important, as in the end it is about me.

(17‐year‐old girl)

This does, however, not mean that parents should be absent or silent during a medical encounter; their involvement is very much appreciated by almost all children. Children considered that parents were able to remember and recall important information, complement children's narratives, introduce things that children had forgotten to say or ask questions that children do not dare to ask themselves. This contrasts with the growing tendency to let children see their medical specialist alone.

Consultation and communication between staff

While children are predominantly positive about communication and relationships with doctors and nursing staff, they express concerns and complain about communication between staff. Problems that were observed include: miscommunication, poor information transfer and conflicting information and advice:

Yesterday all these doctors kept coming up to me and I had to tell all of them the same story over and over again. That is kind of weird. Why don't they write things down?

(12‐year‐old boy)

Another girl commented:

I had a conversation with the doctor about being admitted to hospital. No clear agreements were made about what they were going to do. He thought, I expect, that they would explain it here [nursing ward], and here, they thought he had already done it. So that did not go very well. Everyone thought I already knew everything but that was not true at all. I was rather unhappy about that. It is alright now, because I asked a lot. Everything is clear now. But I was rather unhappy about that.

(15‐year‐old girl)

The example illustrates children's appetite for information but also demonstrates that children are sharp observers rather than passive recipients of care.

Being listened to

Children clearly wish to have a say and to be listened to with regard to both their treatment and the stay in hospital. This was especially the case for chronically ill adolescents who had already been admitted to hospital several times and have extensive knowledge and experience of their condition and treatment. This group of patients specifically want their experience based views to be taken into account, but, unfortunately, this was not always the case:

[…] I told them the drip was not set up properly and that I was not feeling well because of it and that the bed needed to be put back. Then they said: ‘Well, the drip is already in and it is done’ but then I fainted anyway. The bed should have been adjusted. At that time, they did not listen.

(17‐year‐old girl)

The findings also show that children wish to take part in decision‐making processes. For example, some adolescents appreciate being able to choose with whom they share a room or whether they want to be admitted to the children's ward or the adult department. Smaller children, for instance, like to choose whether the anaesthesia is administered by injection or by means of a cap. However, there are many examples that illustrate that children's views and wishes are not always taken into account:

[…] the TV is turned off at a certain time. And the nurse comes by to tell you to go to sleep. I find that a bit strange, I can decide that for myself.

(18‐year‐old girl)

For participation to be successful, it is important that children's contributions are taken into account and acted upon. When children feel that they are not being listened to, they are less likely to make an effort to be heard next time.

Participation, furthermore, calls for an atmosphere in which children are aware of their participation rights and opportunities and feel free to voice their views and preferences and to ask questions:

I dare to ask anything; that's my nature. But I think that everyone could do that here [children's ward]. It's quite open. There's enough opportunity.

(17‐year‐old‐girl)

Some children, however, described situations that demonstrate the contrary:

I would enjoy sharing the same room with someone. I would like that. But I think you do not have a choice. You just have to wait and see where you will end up.

(14‐year‐old boy)

Another boy commented:

I had to get out of bed for the finger prick. But I wanted to stay in bed a little while longer. And I wanted to say that they should come back later, I would like that better, but I cannot do that. But if I could, I would really like that.

(12‐year‐old boy)

These examples illustrate that children are occasionally uncertain about whether they have a choice and that some even keep quiet because they believe they are not allowed to reveal their preferences or think it is inappropriate to do so.

Contact with peers and family

Children wish to have the outside world within reach. It is, therefore, important to them that the right conditions for this are created: access to the Internet, use of mobile phones and unrestricted visiting hours. Children indicate that they do not like to be lonely in hospital and, consequently, express a great desire to be accompanied by familiar people. Children repeatedly mentioned the joy of receiving visits and post cards from family members and friends. Moreover, children very much appreciate their parents having the opportunity to stay overnight.

Modern technologies and social media provide a great opportunity to stay in touch with people at home. Children, for example, mentioned how important it was for them to be able to send text messages to classmates and emails to teachers and to chat online with friends or parents:

The laptop is important. If you're missing your parents, you can talk to them on Hyves [a Dutch social media platform] or Facebook.

(9‐year‐old‐boy)

Children also report enjoying the company of fellow patients. Children consider that playrooms and sitting rooms are a good place to meet others. Furthermore, most children do not mind sharing a room and many even prefer it, preferably if there is someone of their own age to play with or talk to. Some children also stressed that having a roommate reduces the need for parents to stay the night. None of the children disliked the parents of a roommate spending the night in their room because they valued this opportunity themselves and consequently sympathize with children in a similar situation.

Treatment procedures

Children frequently talked about the medical interventions that they undergo. Intrusive procedures that were regarded as unpleasant, frightening and painful were most often mentioned, such as taking blood samples, inserting a drip, receiving injections and inserting stomach tubes. Many children felt that the waiting time before such medical interventions was too long. They felt unhappy about waiting because it makes them even more nervous:

[If I were the boss, I would change this immediately …] It always annoys me that I have to wait a long time for the epidural. The epidural is always given later than the scheduled time which I really don't like because I'm apprehensive.

(6‐year‐old‐girl)

Children, moreover, highlight the importance of guidance and distraction from hospital play specialists during intrusive procedures. However, according to the children, this is not yet sufficiently done in all hospitals:

I want a lot of distraction when I am being injected because that happens too little. It also helps if you get a small reward after the injection because then the end is a bit more fun.

(9‐year‐old girl)

The preferred method of distraction differs per child which means that it is important to ask children what they would prefer and to offer them a choice. Some children, for instance, appreciate having their own soft toy with them while others prefer a small reward, like a toy or sticker.

Hospital facilities and environment

Children had much to say about the hospital facilities and environment. Remarks focused specifically on hospital facilities, poor hospital food, the furnishings and decorations of the paediatric department, and lack of privacy.

Hospital facilities

Children appreciate the many entertainment activities facilitated by the hospital, such as watching television, playing computer games and playing with the hospital play specialists, and spending time in the playroom or the teenager's room. Access to and functioning of some equipment was problematic: poorly working computers, slow Internet connections, broken televisions, and fees for television and Internet use. The latter was especially important for children whose parents could not afford to pay these fees. Children also wished for some more activities for patients aged 12 and over, such as organizing a weekly ‘fun night’ for teenagers that have to stay in hospital for a longer period.

Some adolescents, especially those that stayed in hospital for more than a few days, had concerns about missing lessons and falling behind at school. To maintain schoolwork during hospital admission, children wished for opportunities to go to hospital school, receive individual tuition or to make use of the electronic learning environment offered by many schools, again emphasizing the importance of access to the Internet.

Hospital food

With few exceptions, children had nothing positive to say about hospital food. Several issues were raised repeatedly, including undercooked, unappetizing and non‐fresh food, little variation in the menus and food that does not meet particular cultural or religious dietary requirements:

The main meal of the day should be improved. Often I didn't eat because it doesn't taste nice.

(8‐year‐old‐boy)

Furnishings and decorations

Children attach great value to a colourful decor and furnishing of the rooms and corridors in the children's hospital or department, and they much prefer this to more standard hospital decor:

I once went to a small hospital in Germany. And everything was so sterile and white there. You just felt like: you are alive, but that is all. Compared to that, I like this [hospital] better.

(14‐year‐old boy)

According to children, bright and colourful settings contribute to a pleasant atmosphere. Although all paediatric departments, to a greater or lesser extent, addressed the ‘child‐friendly’ decoration of their unit, children think this still needs improvement in some hospitals and they made a number of suggestions, like message boards and some extra space to display their mail. Children also frequently mentioned the desire for a private toilet and shower. This arises largely from practical considerations. Children, especially those that are extremely weak and/or attached to a drip stand, experience great difficulties getting to toilets in the corridor.

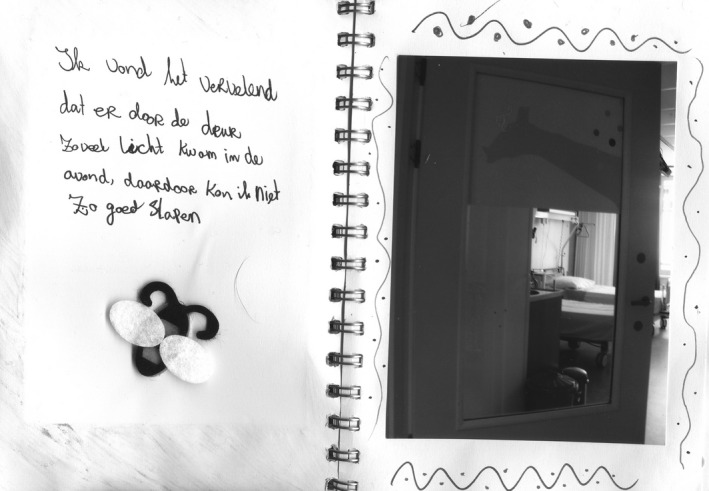

Some children made comments about doors and windows. For example, in one newly built hospital, transparent doors were problematic because they allowed in too much light (Fig. 2). This was especially an issue at night because it causes difficulties with sleeping. In another hospital, one girl complained about a window that could not open:

Figure 2.

Photograph made by a 12‐year‐old‐girl: ‘It bothered me that a lot of light shone through the door at night, I could not sleep very well because of that’.

I cannot get any fresh air in my room, and now I have a cloud in my head. I wish the window could open, like in the room I stayed in last time.

(15‐year‐old girl)

Privacy

One girl explicitly considered the privacy aspect of private shower and toilet facilities:

Actually, every room should have a private shower and toilet, also with regard to privacy. Because if you return from surgery, you do not have any clothes on, except for a blue gown. And then there are many nurses and there are no curtains. I do not feel comfortable with that.

(18‐year‐old girl)

The need for more privacy was also articulated in relation to other environmental issues, such as not having a place to be on your own. As one boy aptly put it:

[I would like] a place to be alone, other than the toilet.

(9‐year‐old boy)

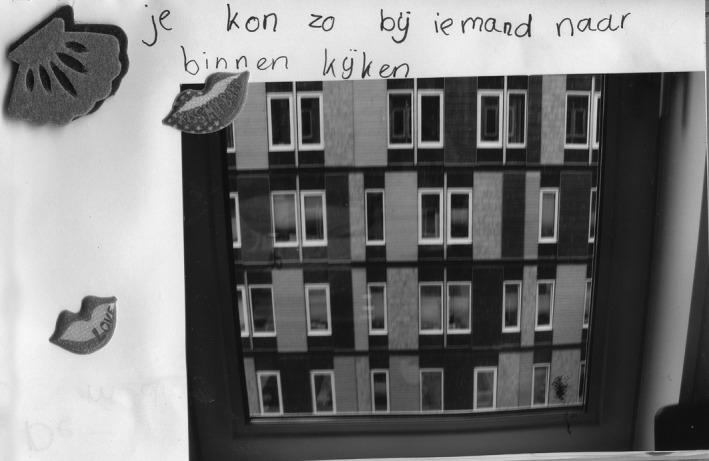

Others experienced the absence of window blinds as a violation of their privacy. One girl, for example, made a photograph (Fig. 3) of the view from her room that shows that the other building is very near and that blinds are absent, making it possible to look inside someone else's room.

Figure 3.

Photograph made by a 13‐year‐old‐girl: ‘You could easily look into someone else's room’.

Discussion

The object of this study was to investigate children's experiences with paediatric hospital care in order to consider the feasibility of creating health‐care services that more closely meet children's own needs and wishes. Some findings may not seem interesting because they have long been known. Despite this knowledge, major aspects of health and well‐being of ill and diseased children, such as nutrition that fits their preferences and being able to sleep well, are structurally being neglected in hospitals. Children's priorities for hospital care and services are well‐documented, but they are often not acted upon. Our study established that participatory methods have the potential to promote direct action and bring about meaningful changes.

Health and social well‐being of children in hospital

The importance of a healthy diet and being responsive to children's general sleeping habits may seem self‐evident, especially when considering that this directly contributes to the healing process. The need for window blinds so that children can sleep in darkness (Fig. 2) seems obvious but had been completely overlooked when designing the new children's ward in one of the hospitals in our study.

Other key findings underline the importance of taking into account social aspects that are known to greatly affect children's subjective well‐being, including relationships with family, friends and peers.35, 36 Children repeatedly mentioned that they were happy when parents could stay the night and when they received visits from family members and friends. This is consistent with the findings of Pelander & Leino‐Kilpi37 who reported that separation from parents and family, friends, home and school were children's worst experiences during hospitalization. Wilson et al.38 made similar observations from research with school‐aged children who indicated being alone as a primary fear of hospitalization that makes them feel ‘scared, mad and sad.’ This evidence reaffirms the importance of hospital policies, including unrestricted visiting hours and the possibility for parents to room‐in with their hospitalized child, that have been introduced over the last 20 years in an attempt to make hospitals more child‐friendly places.

Children, and in particular adolescents, also highlighted the need for electronic communication with people outside the hospital using mobile phones and the Internet for both social and educational reasons. This is not surprising given that the popularity and use of such technologies has increased considerably among children over recent years, even faster than among the rest of the population,39 and has become an integral part of young people's daily lives, allowing them to maintain relationships with friends and peers.40 Increasing numbers of schools in the Netherlands make use of electronic learning environments, which means that it is important that children in hospital, especially those admitted for longer periods of time, have access to a computer with Internet in order to keep up with school.

Children complained about broken computers, slow Internet connections and fees for Internet use, leading us to suggest that some hospitals are lagging behind the rapid technological developments in society. Lambert et al.41 drew similar conclusions from research with young children (5–8 years), arguing that health care has been slow in keeping up with global advancements in children's use of social technologies. Hospitals need to consider how to facilitate children's technological connectivity, important for both their social and school lives. This may be even more crucial for adolescents because peers are more important in their lives and play a substantial role in their psychosocial development.39 For example, Kendall et al.42 suggested that the psychosocial impact of congenital cardiac disease on adolescents, such as disruption of social relationships, may play a greater role in determining self‐perceived health than the physical limitations they experience.

Many of the other topics that participants raised support findings from previous studies, such as children's preference for a warm and colourful decor,19 more privacy,43, 44 complaints about poor hospital food,45, 46 the need for sufficient preparation and guidance during stressful medical interventions38, 46and the importance of good relationships45, 47, 48 and effective communication49, 50, 51 with hospital staff. Lightfoot & Sloper,2 for example, showed that young people with a chronic illness or physical disability find staff communication with patients to be of key importance.

Given that these topics have long been recognized and highlighted by a number of authors, no further evidence is required to demonstrate that these are major issues for children. Instead, hospital staff need to acknowledge and act upon them. As Curtis and colleagues45 point out, practitioners and managers are often poor at acting on such knowledge, although we did not find that in this study.

Methodological strengths

Many of the children's needs and areas for improvement identified during this study were acted upon by the hospitals. Examples include blinding of doors and windows and developing child‐friendly menus that have been tasted and assessed by a specially established team. Other action points could not be addressed immediately but are now receiving attention or have been placed high on the agenda. We believe that the participatory approach taken in this study has played an essential role in motivating hospitals to take direct action upon the issues identified by the children. The methodology has a number of strengths which supported implementation of the findings.

First, our approach acknowledged that children are experts about their own lives, and we provided them with the opportunity to tell their own stories. Second, it facilitated direct communication between young patients and hospital management, giving children the unusual opportunity to speak up and be heard in their own words, without parents or researchers interpreting their words or acting as their spokespersons. Third, photovoice was able to provide visual metaphors of what the children wanted to tell.52 Finally, the data produced by children generated concrete points for improvement to which hospital managers were able to respond.

Participatory methods are uncommon and not well accepted in hospital settings34 as a result of widespread unfamiliarity with the participatory philosophy and an ideological clash with the medical paradigm. However, in our opinion, participatory methods have greater potential to bring about changes that matter to children than traditional social research methods. For this reason, we recommend that participatory approaches should be employed to evaluate hospital care with children on a structural basis. Hospital managers should be involved from the very start in order to make sure that they fully embrace the initiative. Ultimately, children and young people are dependent on policymakers and hospital managers to implement participant's needs and create more responsive health‐care services.

Conclusion

Using a number of participatory research methods, children and young people were very eager to share their experiences. The strength of this participatory approach is that it brought children's ideas ‘alive’ and generated concrete areas for improvement that stimulated hospitals to actually address and act upon the issues raised by children. This demonstrates that participatory methods are not merely tools to gather children's views but can serve as vehicles for making changes that matter.

Source of funding

This research project was funded by Fonds PGO, an executive organization of the Dutch government that provides grants on behalf of the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport.

Acknowledgements

The study was executed in close co‐operation with the Dutch Child & Hospital Foundation and Zorgbelang, a national patient organization in the Netherlands. We would like to thank the children and young people who participated in the study, and all hospital staff members involved for their dedication to this project. We are also grateful to Sarah Cummings for editing our writing and to Kim van Dijk for her assistance in translating children's quotations cited in this paper.

References

- 1. Sinclair R. Participation in practice: making it meaningful, effective and sustainable. Children & Society, 2004; 18: 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lightfoot J, Sloper P. Having a say in health: involving young people with a chronic illness or physical disability in local health services development. Children & Society, 2003; 17: 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hallström I, Elander G. Decision‐making during hospitalization: parents' and children's involvement. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2003; 13: 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aynsley‐Green A, Barker M, Burr S, et al Who is speaking for children and adolescents and for their health at the policy level. British Medical Journal, 2000; 321: 229–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clavering EK, McLaughlin J. Children's participation in health research: from objects to agents? Child: Care, Health and Development, 2010; 36: 603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Council of Europe . Guidelines on child‐friendly health care. Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 21 September 2011.

- 7. Tates K, Meeuwesen L. ‘Let mum have her say’: turntaking in doctor‐parent‐child communication. Patient Education and Counseling, 2000; 40: 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Staa A, Jedeloo S, Latour JM, Trappenburg MJ. Exciting but exhausting: experiences with participatory research with chronically ill adolescents. Health Expectations, 2010; 13: 95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dedding C. Delen in macht en onmacht. Kindparticipatie in de (alledaagse) diabeteszorg [Sharing power and powerlessness. Child participation in the (ordinary) diabetes care]. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vis SA, Strandbu A, Holtan A, Thomas N. Participation and health ‐ a research review of child participation in planning and decision‐making. Child & Family Social Work, 2011; 16: 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Runeson I, Hallström I, Elander G, Hermerén G. Children's participation in the decision‐making process during hospitalization: an observational study. Nursing Ethics, 2002; 9: 583–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carter B. Chronic pain in childhood and the medical encounter: professional ventriloquism and hidden voices. Qualitative Health Research, 2002; 12: 28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coyne I. Consultation with children in hospital: children, parents' and nurses' perspectives. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2006; 15: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coyne I, Harder M. Children's participation in decision‐making: balancing protection with shared decision‐making using a situational perspective. Journal of Child Health Care, 2011; 15: 312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alderson P, Sutcliffe K, Curtis K. Children as partners with adults in their medical care. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 2006; 91: 300–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coyne I. Children's participation in consultations and decision‐making at health service level: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2008; 45: 1682–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goodenough T, Kent J. ‘What did you think about that?’ Researching children ‘s perceptions of participation in a longitudinal genetic epidemiological study. Children & Society, 2003; 17: 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moore L, Kirk S. A literature review of children's and young people's participation in decisions relating to health care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2010; 19: 2215–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kilkelly U. Child‐friendly health care: the views and experiences of children and young people in Council of Europe member States. 2011.

- 20. Van Staa A, Jedeloo S, van der Stege H. ‘What we want’: chronically ill adolescents' preferences and priorities for improving health care. Patient Preference and Adherence, 2011; 5: 291–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beresford BA, Sloper P. Chronically ill adolescents' experiences of communicating with doctors: a qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2003; 33: 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ygge BM, Arnetz JE. Quality of paediatric care: application and validation of an instrument for measuring parent satisfaction with hospital care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2001; 13: 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ammentorp J, Rasmussen AM, Nørgaard B, Kirketerp E, Kofoed P‐E. Electronic questionnaires for measuring parent satisfaction and as a basis for quality improvement. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2007; 19: 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith B, Ganser CMC, Brustowicz RM, Goldmann DA. Quality of care at a children's hospital. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 2011; 153: 1123–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Knopf JM, Hornung RW, Slap GB, DeVellis RF, Britto MT. Views of treatment decision making from adolescents with chronic illnesses and their parents: a pilot study. Health Expectations, 2008; 11: 343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christensen P, Prout A. Working with ethical symmetry in social research with children. Childhood, 2002; 9: 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coad JE, Shaw KL. Is children's choice in health care rhetoric or reality? A scoping review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2008; 64: 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dedding C, Schalkers I, Willekens T. Children's Participation in Hospital. A Short Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Involving Children in Improving Quality of Care. Utrecht: Stichting Kind & Ziekenhuis, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Langhout RD, Thomas E. Imagining participatory action research in collaboration with children: an introduction. American Journal of Community Psychology, 2010; 46: 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mason J, Hood S. Exploring issues of children as actors in social research. Children and Youth Services Review, 2011; 33: 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lundy L, McEvoy L. Children's rights and research processes: assisting children to (in)formed views. Childhood, 2011; 19: 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsieh H‐F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 2004; 24: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carter B, Ford K. Researching children's health experiences: the place for participatory, child‐centered, arts‐based approaches. Research in Nursing & Health, 2013; 36: 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adamson P. Child Well‐being in Rich Countries. A Comparative Overview. Florence: Unicef Office of Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rees G, Goswami H, Pople L, Bradshaw J, Keung AMG. The Good Childhood Report 2012. A review of our children ‘s well‐being. 2012.

- 37. Pelander T, Leino‐Kilpi H. Children's best and worst experiences during hospitalisation. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 2010; 24: 726–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilson ME, Megel ME, Enenbach L, Carlson KL. The voices of children: stories about hospitalization. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 2010; 24: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kuntsche E, Simons‐Morton B, ter Bogt T, et al Electronic media communication with friends from 2002 to 2006 and links to face‐to‐face contacts in adolescence: an HBSC study in 31 European and North American countries and regions. International Journal of Public Health, 2009; 54: 243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A et al Social determinants of health and well‐being among young people. Health behaviour in school‐aged children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen; 2010.

- 41. Lambert V, Coad J, Hicks P, Glacken M. Social spaces for young children in hospital. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2013; 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kendall L, Lewin RJP, Parsons JM, et al Factors associated with self‐perceived state of health in adolescents with congenital cardiac disease attending paediatric cardiologic clinics. Cardiology in the Young, 2001; 11: 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pelander T, Leino‐Kilpi H. Quality in pediatric nursing care: children's expectations. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 2004; 27: 139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ekra EMR, Gjengedal E. Being hospitalized with a newly diagnosed chronic illness—A phenomenological study of children's lifeworld in the hospital. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well‐Being, 2012; 7: 18694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma KC, Liabo K, Dphil HR, Ffphà MB, Curtis K. Consulted but not heard: a qualitative study of young people ‘s views of their local health service. Health Expectations, 2004; 7: 149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Coyne I. Children's experiences of hospitalization. Journal of Child Health Care, 2006; 10: 326–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jackson AM. ‘Follow the Fish’: involving young people in primary care in Midlothian. Health Expectations, 2003; 6: 342–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Livesley J, Long T. Children's experiences as hospital in‐patients: voice, competence and work. Messages for nursing from a critical ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 2013; 50: 1292–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lambert V, Glacken M, McCarron M. Communication between children and health professionals in a child hospital setting: a child transitional communication model. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2011; 67: 569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tates K, Meeuwesen L. Doctor–parent–child communication. A (re)view of the literature. Social Science & Medicine, 2001; 52: 839–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Birks Y, Sloper P, Lewin R, Parsons J. Exploring health‐related experiences of children and young people with congenital heart disease. Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 16–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lorenz LS, Kolb B. Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expectations, 2009; 12: 262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]