Abstract

Background and purpose

[18F]Fluoride ([18F]NaF) PET scan is frequently used for estimation of bone healing rate and extent in cases of bone allografting and fracture healing. Some authors claim that [18F]NaF uptake is a measure of osteoblastic activity, calcium metabolism, or bone turnover. Based on the known affinity of fluoride to hydroxyapatite, we challenged this view.

Methods

10 male rats received crushed, frozen allogeneic cortical bone fragments in a pouch in the abdominal wall on the right side, and hydroxyapatite granules on left side. [18F]NaF was injected intravenously after 7 days. 60 minutes later, the rats were killed and [18F]NaF uptake was visualized in a PET/CT scanner. Specimens were retrieved for micro CT and histology.

Results

MicroCT and histology showed no signs of new bone at the implant sites. Still, the implants showed a very high [18F]NaF uptake, on a par with the most actively growing and remodeling sites around the knee joint.

Interpretation

[18F]NaF binds with high affinity to dead bone and calcium phosphate materials. Hence, an [18F]NaF PET/CT scan does not allow for sound conclusions about new bone ingrowth into bone allograft, healing activity in long bone shaft fractures with necrotic fragments, or remodeling around calcium phosphate coated prostheses

Positron emission tomography using the [18F]NaF (18F PET scan) can be used for visualization of the skeleton, much in the same way as the well-established technetium-bisphosphonate scans ([Tc99m]Tc-HDP, [Tc99m]Tc-MDP), but with better resolution. The latter method has been used for many decades, most commonly in the search for skeletal metastases. It has become a common assumption among clinicians that a high uptake on a technetium scan indicates a high bone turnover, and the same tenet seems to have been applied to the 18F PET scan.

Like Tc-labelled bisphosphonates, fluoride ions have a high affinity to hydroxyapatite. This small ion diffuses freely in soft tissues and can pass through membranes. It reaches the mineral surfaces quickly after injection (Czernin et al. 2010, Li et al. 2012). However, living bone is covered by a cell layer that limits its access to the mineral, but dead bone and hydroxyapatite implants expose their binding sites more directly. Therefore, one would expect these materials to show a high uptake.

[18F]NaF PET scan has been used in studies claiming new bone ingrowth into morsellized allografts in hip revision already a week after implantation (Sörensen et al. 2003, Ullmark et al. 2007), for estimation of shaft fracture healing rate (Cheng et al. 2014, Lundblad et al. 2014) and for claiming that hydroxyapatite-coated implants cause an increased local bone formation rate (Ullmark et al. 2012). The aforementioned studies are just examples from a wider orthopedic literature, in which there seems to be consensus that [18F]NaF PET scans exclusively reflect bone formation or metabolism.

We wish to challenge this consensus by presenting a simple rat experiment, where dead bone fragments and hydroxyapatite granules were implanted intramuscularly in rats and analyzed after 7 days. New intramuscular bone formation is unlikely to follow upon this procedure and could be excluded by histology.

Methods

Overview

10 male Sprague Dawley rats with a mean weight of 630 g (SD 27) received grafts of crushed, frozen allogeneic cortical bone fragments in a muscle pouch in the abdominal wall on the right side, and hydroxyapatite granules on the left side. They also had a drill hole made in the right proximal tibia.

[18F]NaF was produced on the 9.6MeV MiniTrace cyclotron and [18F]NaF was administered by injection in a tail vein 7 days after grafting. 60 minutes later, the rats were killed with CO2 and [18F]NaF activity was visualized in a PET scanner. Specimens were retrieved for micro CT and histology.

Surgical procedure

The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane gas. Each rat received a subcutaneous injection of 7 mg oxytetracycline as infection prophylaxis and 0.015 mg buprenorphine as postoperative analgesic. Analgesic was given every 12 hours for the following 48 hours. The right hind leg and the abdomen were shaved and cleaned with chlorhexidine. The rat was placed in a surgical glove and 2 holes were cut in the glove, through one of which the shaved leg was pulled out; the other was big enough to expose the shaved abdomen. Sterile tape was wrapped around the paw and the leg and the abdomen were cleaned once more with chlorhexidine.

2 longitudinal incisions (approximately 10 mm) were made bilaterally, exposing the oblique muscles lateral to the rectus abdominis. Muscle pouches, approximately 3 × 5×5 mm in size, were created and filled with either allogenic cortical bone fragments or hydroxyapatite granules. The pouches were closed with a suture and the skin was then sutured. A 5–6 mm longitudinal incision was made along the rat tibia, and a hole was drilled by hand in the anteromedial surface of the proximal metaphysis, about 3 mm from the growth plate, using a 1.2 mm syringe needle. The skin was then sutured.

Grafting material

The synthetic grafting material used (Hydroset, Stryker, MI, USA) is a self-setting calcium phosphate cement that forms hydroxyapatite. The grafting material was shaped into small, pea-sized balls and allowed to set. Thereafter each ball was crushed into a mix of varying granule size.

The allogenic grafting material consisted of femurs from Sprague Dawley rats. The entire femurs were taken out, stripped of muscle and frozen at –20 °C for 2 weeks. Thereafter, they were thawed and ground with a pestle to a mash of small pieces of bone and marrow. No attempt was made to remove the marrow. The mash was frozen for 3 days and thawed in time for surgery.

18F PET scan

104 MBq (SD 34) of [18F]NaF was administered by intravenous tail injection after 7 days. The activity of each syringe was measured prior to and following injection in a dose calibrator. 60 minutes post-injection the rats were killed with CO2 and placed in a Discovery 710 PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). PET acquisition from head to tail was acquired with a field of view (FOV) of 30 cm, 256 × 256 matrix and 3 minutes per bed position. CT conditions were set to 120 kV and a Smart-auto beam current of 10–200 mA. Acquired images were reconstructed with the iterative Bayesian penalized likelihood algorithm Q.Clear and transferred to an AW-server for visualization and quantification of the [18F]NaF activity in the implants and reference sites. The peak standard uptake value (SUVpeak, kBq/cm3) was obtained for a volume of 1.4 cm3 at the location of the 2 implants and 2 reference sites (left and right knee joint) for each animal.

The semi-quantitative method of peak standardized uptake value (SUV peak) of [18F]NaF was used to assess the uptake in the 2 implants and corresponding reference sites. SUV peak is defined as the average SUV within a small fixed-size volume centered on the uptake region. SUV peak is considered to be less affected by image noise compared with the single-pixel value of SUV max and therefore is expected to reduce uncertainties in the quantification (Krak et al. 2005, Nahmias et al. 2008).

Micro CT

The right tibia and muscle tissue specimens were analyzed with micro CT (Skyscan 1174, v. 2; Bruker, Aarteselaar, Belgium). Topographic images of the bones with an isotropic voxel size of 16.4 µm were acquired at energy settings of 50 kV and 800 µA, using an aluminum filter of 0.5 mm, rotation step of 0.4° and frame averaging of 3. The images were reconstructed with NRecon (Skyscan, v. 1.6.8.0; Aarteselaar, Belgium) and corrected for ring artifacts and beam hardening.

Histology

The specimens were decalcified in 10% EDTA, dehydrated in a series of increasing concentration of ethanol and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. The muscle pouch specimens were sectioned perpendicular to the plane of the muscle layer and the tibiae were sectioned longitudinally in 4 µm sections and stained with HE.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board in Linköping, Sweden, in accordance with the Swedish Animal Welfare Act (1988:534) and EU-Directive 2010/63/EU. The registration ID is 49-15. The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (2031-47-5), AFA insurance company, EU 7th framework program (FP7/2007-2013, grant 279239) and a specific grant from Linköping University. No competing interests declared.

Results

Exclusions

2 animals died postoperatively for unknown reasons.

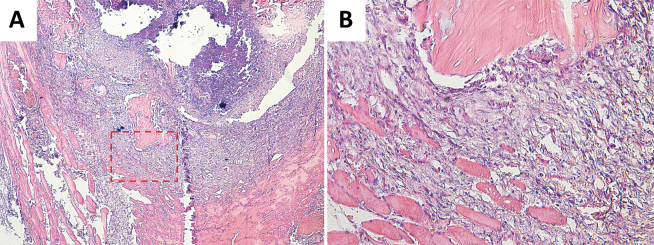

18F PET scan qualitative

In all animals, the sites with both implanted allogeneic bone and hydroxyapatite granules were easily detected by strong, distinctly localized [18F]NaF uptake (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PET images of the [18F]NaF uptake in grafts in the transverse (A) and coronal plane (B). Both of the sites (red circles) with implanted allogeneic bone (right side) and hydroxyapatite granules (left side) were easily distinguished in all animals.

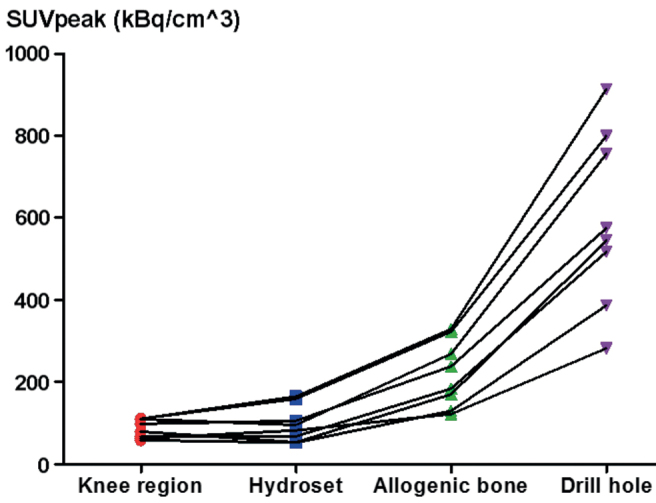

18F PET scan quantitative

The analyzed images resulted in a similar SUV peak for both types of implants. The implants showed a considerably higher uptake than the untraumatized knee. The knee on the traumatized side showed the highest uptake of all sites (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PET analysis of [18F]NaF uptake (SUV peak) at different sites. Each line connects the data from one individual animal. Both grafts showed a higher 18F uptake than the knee region. The tibia with the former drill hole showed the highest 18F uptake.

Micro CT

Images confirmed that the allogenic bone and hydroxyapatite grafts were intact in the tissue samples. The drill holes in the proximal tibiae were filled with new woven bone (Supplementary Figure 6).

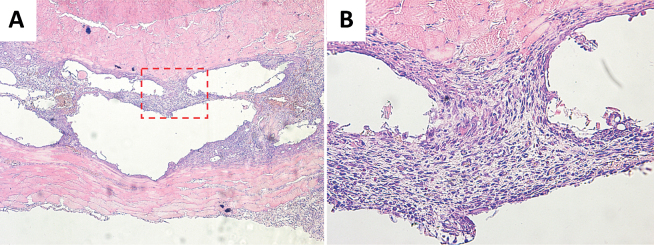

Histology

The allogenic bone fragments were surrounded by a granuloma inside the muscle pouch (Figure 3). The granuloma was dominated by inflammatory cells with only a little fibrosis. There were no signs of cartilage or bone formation. Osteocyte lacunae in the allogenic bone were empty.

Figure 3.

Histology images of allogenic bone fragments in muscle pouch (A 4×; B 20×). A granuloma, dominated by inflammatory cells, could be seen adjacent to the allogenic bone fragments. Osteocyte lacunae were empty in the fragments and no cartilage or bone formation could be seen.

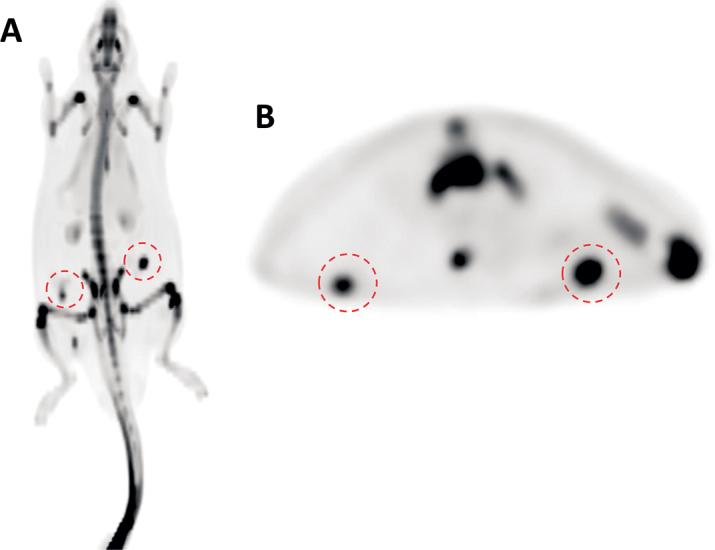

The hydroxyapatite granules had been dissolved during decalcification, leaving empty cavities in the tissue, surrounded by a granuloma similar to that surrounding the allogeneic bone (Figure 4). No cartilage or bone could be seen bordering the cavities where the granules had been, or elsewhere.

Figure 4.

Histology images of hydroxyapatite granules in muscle pouch (A 4×; B 20×). The tissue between the two muscle layers consisted of granuloma and empty cavities from the hydroxyapatite granules, which had been dissolved during decalcification. No cartilage or bone could be seen bordering the cavities where the granules had been, or elsewhere.

Discussion

We have shown high [18F]NaF PET activity in necrotic bone and hydroxyapatite granules in a muscle pouch without any histologic sign of living bone. If these materials had been inserted as bone replacements in a fracture, or at an implant, the “shining dead bone” could have led to false conclusions regarding the efficacy of grafting or bone replacement. Such conclusions seem common in the literature. We have not investigated the 18F PET activity in osteonecrosis (bone infarct), which is probably another situation where one could expect “shining dead bone” after revascularization.

For the [18F]NaF to reach the dead bone, a capillary network needs to be established. This may take some time, and the increasing [18F]NaF activity over time due to revascularization might have misled investigators to believe that it reflected bone ingrowth.

The [18F]NaF PET scan is an important tool for many purposes, such as the search for metastases. When dealing with bone grafts or other implanted minerals, it must not be forgotten, however, that the method is based on the affinity of fluoride to such materials and that the ion can reach the mineral surfaces directly via passive diffusion, without any involvement of osteoblasts.

Supplementary data

Details of PET (Figure 5), micro CT (Figure 6), and histology images (Figures 7–9) are available in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1372097

PA, OS, and MB planned the study. OS and MB conducted the surgery. JK and JM were responsible for production and handling of [18F]NaF. MR conducted the [18F]NaF PET scan. PA and MB did the data analysis. PA and MB wrote the manuscript draft, which was revised by all authors.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cheng C, Alt V, Pan L, Thormann U, Schnettler R, Strauss L G, Schumacher M, Gelinsky M, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A.. Preliminary evaluation of different biomaterials for defect healing in an experimental osteoporotic rat model with dynamic PET-CT (dPET-CT) using F-18-sodium fluoride (NaF). Injury 2014; 45 (3): 501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czernin J, Satyamurthy N, Schiepers C.. Molecular mechanisms of bone 18F-NaF deposition. J Nucl Med 2010; 51 (12): 1826–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Schiepers C, Lake R, Dadparvar S, Berenji GR.. Clinical utility of (18)F-fluoride PET/CT in benign and malignant bone diseases. Bone 2012; 50 (1): 128–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundblad H, Maguire G Q J, Olivecrona H, Jonsson C, Jacobsson H, Noz M E, Zeleznik M P, Weidenhielm L, Sundin A.. Can Na18F PET/CT be used to study bone remodeling in the tibia when patients are being treated with a Taylor Spatial Frame? ScientificWorldJournal 2014; 2014: 249326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krak N C, Boellaard R, Hoekstra O S, Twisk J W R, Hoekstra C J, Lammertsma A A.. Effects of ROI definition and reconstruction method on quantitative outcome and applicability in a response monitoring trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2005; 32: 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahmias C, Wahl L M.. Reproducibility of standardized uptake value measurements determined by 18F-FDG PET in malignant tumors. J Nucl Med 2008; 49: 1804–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen J, Ullmark G, Långström B, Nilsson O.. Rapid bone and blood flow formation in impacted morselized allografts: Positron emission tomography (PET) studies on allografts in 5 femoral component revisions of total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74 (6): 633–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmark G, Sörensen J, Långström B, Nilsson O.. Bone regeneration 6 years after impaction bone grafting: A PET analysis. Acta Orthop 2007; 78 (2): 201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmark G, Sörensen J, Nilsson O.. Analysis of bone formation on porous and calcium phosphate-coated acetabular cups: A randomised clinical [18F]fluoride PET study. Hip Int 2012; 22 (2): 172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.