Abstract

Background and purpose

Mortality rates following hip fracture (HF) surgery are high. We evaluated the influence of the basic mobility status on acute hospital discharge to 1- and 5-year mortality rates after HF.

Patients and methods

444 patients with HF ≥60 years (mean age 81 years, 77% women) being pre-fracture ambulatory and admitted from their own homes, were consecutively included in an in-hospital enhanced recovery program and followed for 5 years. The Cumulated Ambulation Score (CAS, 0–6 points, 6 points equals independence) was used to evaluate the basic mobility status on hospital discharge.

Results

102 patients with a CAS <6 stayed in the acute ward a median of 22 (15–32) days post-surgery as compared with a median of 12 (8–16) days for those 342 patients who achieved a CAS =6. Overall 1-year mortality was 16%; in those with CAS <6 it was 30% and in those with CAS =6 it was 12%. Corresponding data for 5-year deaths were 78% and 50%. Multivariable Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the likelihood of not surviving the first 5 years after hip fracture was 1.5 times higher for those with a CAS <6 and for men; 2 times higher for those 80 years or older; increased by 50% per point higher ASA grade; and was reduced by 11% per point higher New Mobility Score, when adjusted for the cognitive and fracture type status.

Interpretation

Further studies focused on interventions that improve the basic mobility status of patients with HF should be instigated within the early time period following surgery.

The mortality rate following hip fracture (HF) surgery is high and has a multifactorial pathogenesis (Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014, Nikkel et al. 2015). The influence of potentially modifiable factors, such as the post-surgery ambulatory level, on long-term mortality rates seems less studied compared with preoperative risk factors (Kristensen 2011, Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014). Yet, some data suggest that post-surgery walking ability as opposed to bedridden or wheelchair status, the ability to stand up versus not, the post-surgery time to ambulation, and a decreased combined balance and gait score may predict long-term mortality following HF (Hoenig et al. 1997, Fox et al. 1998, Gdalevich et al. 2004, Siu et al. 2006, Panula et al. 2009, Dubljanin-Raspopovic et al. 2013, Iosifidis et al. 2016).

However, the influence of the post-surgery basic mobility level, as evaluated with the easily applicable, reliable and standardized Cumulated Ambulation Score (CAS) (Foss et al. 2006, Kristensen et al. 2009), on long-term mortality rates following HF has not been studied.

The main aim of this study was to examine whether the basic mobility status on acute hospital discharge was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 1 and 5 years after HF surgery when adjusted for important pre-surgery risk factors as reported in 2 meta-analyses (Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014). Secondary aims were to determine the relative role of the 3 basic mobility activities evaluated with the CAS: bed, chair, and walking skills, to a non-independent status, and whether the length of hospital stay (LOS) influenced post-discharge mortality rates.

Patients and methods

Patients

493 pre-fracture ambulatory patients with HF admitted from their own homes, who followed a multidisciplinary enhanced recovery program at the orthopedic hip fracture unit, Hvidovre Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and who were discharged from the acute hospital, were studied in 2 consecutive prospective cohorts (Kristensen et al. 2010, Kristensen and Kehlet 2012). Patients who also had other fractures than the hip fracture, surgical restrictions of mobilization, re-surgery during admittance, early transfer to medical wards or “home” hospital, and thereby were not able to follow the enhanced program were excluded from the 2 previous studies. Further, those who died during admittance in the orthopedic ward were not included. We excluded 47 patients younger than 60 years of age and 2 foreigners, and thus 444 patients were included in the present study.

Primary and secondary exposures

The CAS (Foss et al. 2006), which evaluates independence in the 3 basic mobility activities—getting in and out of bed, sit-to-stand-to-sit in a chair with arms (seat height approximately 45cm), and indoor walking with or without a walking aid—was used as the primary exposure. The distribution of CAS scores (0 = not able to despite human assistance and verbal cueing, 1 = able to, with human assistance and/or verbal cueing from one or more persons, or 2 = able to safely, without human assistance or verbal cueing) for each of the 3 CAS activities (Kristensen et al. 2009), and the cumulated 1-day CAS score (0–6 points) were collected from the routine physical therapist score sheets. The CAS is an obligatory national register score reported to the Danish Multidisciplinary Hip Fracture Database, with the pre-fracture and acute hospital discharge CAS score reported, enabling calculation of a change score, reflecting the early rehabilitation outcome. Also, the CAS is used in other countries (Piscitelli et al. 2012, Taraldsen et al. 2014). The post-surgery LOS in days was used as a secondary exposure.

Adjustment variables

The adjustment variables to the basic mobility status on hospital discharge were age, sex, pre-fracture function evaluated with the reliable and modified New Mobility Score (NMS, 0–9 points) (Kristensen and Kehlet 2012), cognitive status, fracture type, and the ASA grade (1–4 points), which are among the key preoperative characteristics associated with the long-term risk of mortality, as shown in recent meta-analyses (Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome, the date of death within 5 years following the index hip fracture surgery, was obtained retrospectively from the Danish Civil Registration system and transformed into post-surgery days to death. Also, as a secondary outcome, post-discharge days to death was recorded for the evaluation of the potential association with LOS (Nordstrom et al. 2015, Nikkel et al. 2015).

Discharge criteria

The functional discharge criteria for patients being discharged directly back to own home were standardized, and included the ability independently to: get in and out of bed, sit to stand to sit from a chair with arms, and walk with an aid to be used in the home, as evaluated with the CAS score, and getting to and from a place of eating and manage toilet. Functional discharge criteria for patients with hip fracture are seldom reported, but although used in the present fast-track program, patients are far from being considered fully rehabilitated at the time of hospital discharge, even if fulfilling these criteria.

Statistics

Patient characteristics for those who died were compared with those alive at 1-year post-surgery using Student’s t-test for age (Q-Q plots indicated a normal distribution), the Mann–Whitney test for post-surgery LOS, and chi-square tests for sex, pre-fracture function (NMS, 2–5 versus 5–9 points), cognitive status, ASA grades (1–2 versus 3–4), fracture type (femoral neck versus trochanteric), type of surgery, discharge destination (own home versus 24-hour rehabilitation setting or nursing home), and the basic mobility CAS status on discharge. The CAS was dichotomized as independent (CAS =6) as opposed to not independent (CAS <6).

The variables mentioned above, except for the type of surgery (dependent on the fracture type), LOS and discharge destination (highly associated with the basic mobility status on discharge), were entered into a multivariable Cox proportional hazards models including 95% confidence intervals (CI) to examine their influence on the 1-year and 5-year post-surgery mortality rates. The NMS and ASA grade were entered as continuous variables, while age was entered in decades. Log-minus-log versus log of survival time graphs in the 2 Cox models showed parallel curves for the independent and non-independent basic mobility group. Corresponding Kaplan–Meier survival graphs were generated for the 2 CAS groups, and for the 1-year post-discharge mortality and LOS (grouped as 0–5, 6–10, 11–14, and >14 days) (Nikkel et al. 2015). Data are presented as mean (SD) if normally distributed, otherwise as median (25–75% quartiles) or as number (percentage). A p-value below 0.05 was considered significant; GraphPad software (San Diego, CA, USA) and SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, BY, USA) were used for the statistical analyses.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and data collection within the study period was registered with the data protection agency (2003-41-3113). No funding was received for the present study, and the authors report no conflict of interest.

Results

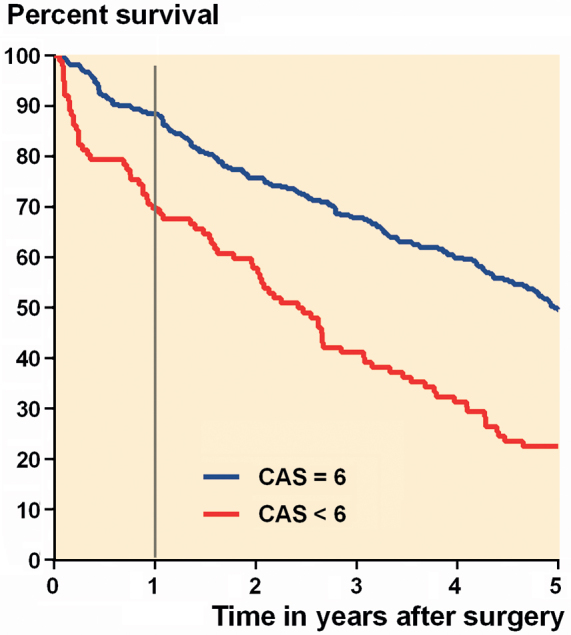

Characteristics of the 444 pre-fracture ambulatory patients (aged ≥60 years), of whom 71 (16%) and 251 (57%), respectively, died within 1 and 5 years post-surgery, are reported in Table 1. 102 (23%) patients were discharged from the acute hospital without reaching an independent basic mobility status (CAS <6) and stayed more days (median of 22 [15–32]) in the acute hospital, as compared with the independent (CAS =6) group with 12 [8–16] days (p < 0.001). 83 (81%) patients in the non-independent group were discharged to further rehabilitation or permanent nursing home, compared with 30 (9%) in the independent group. 79 (78%) patients in the non-independent group died within the 5-year follow-up period compared with 172 (50%) in the independent group (p < 0.001). The 1-year and 5-year survival rates for the non-independent group were 66% (HR =0.34, CI 0.14–0.43) and 55% (HR =0.45, CI 0.26–0.50) lower than in the independent group, respectively (Figure 1). The Mantel–Cox log-rank survival distribution tests also differed: x2(1) = 23 (p < 0.001) and x2(1) = 36 (p < 0.001), and, compared with the non-independent group, the post-surgery survival times were longer for patients in the independent group, with a mean of 341 (CI 334–349) days as opposed to 297 (CI 273–320) days for 1-year survival and 3.7 (CI 3.5–3.8) years as opposed to 2.5 (CI 2.2–2.9) years for 5-year survival.

Table 1.

Characteristics and 1-year mortality: values are mean (SD) for age and median (IQR) for the length of stay; otherwise, number (%)

| Alive 1-year post-surgery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | Yes | No | ||

| Variables | n = 444 | n = 373 (84) | n = 71 (16) | p-value |

| Age, years | 81.4 (8.5) | 81.2 (8.5) | 82.9 (8.0) | 0.1 |

| Men | 103 (23) | 80 (78) | 23 (22) | 0.05 |

| Women | 341 (77) | 293 (86) | 48 (14) | |

| New Mobility Score 2–4 points | 156 (35) | 116 (74) | 40 (26) | < 0.001 |

| New Mobility Score 5–9 points | 288 (65) | 257 (89) | 31 (11) | |

| Low cognitive status | 86 (19) | 68 (79) | 18 (21) | 0.2 |

| High cognitive status | 358 (81) | 305 (85) | 53 (15) | |

| ASA grade 1–2 | 244 (55) | 219 (90) | 25 (10) | < 0.001 |

| ASA grade 3–4 | 200 (45) | 154 (77) | 46 (23) | |

| Femoral neck fracture | 225 (51) | 196 (87) | 29 (13) | 0.07 |

| Trochanteric fracturea | 219 (49) | 177 (81) | 42 (19) | |

| 2 screws/nails | 60 (15) | 58 (97) | 2 (3) | 0.1 |

| Hemiarthroplasty | 139 (31) | 115 (83) | 24 (17) | |

| Total arthroplasty | 6 (1) | 6 (100) | n/a | |

| Dynamic Hip Screw with 2-hole plate | 18 (4) | 15 (83) | 3 (17) | |

| Dynamic Hip Screw with 4-hole plate | 179 (40) | 145 (81) | 34 (19) | |

| Short intramedullary hip screw | 24 (5) | 20 (83) | 4 (17) | |

| Long intramedullary hip screw | 18 (4) | 14 (78) | 4 (22) | |

| Discharged to previous residence | 331 (75) | 289 (87) | 42 (13) | 0.001 |

| Not discharged to previous residence | 113 (25) | 84 (74) | 29 (26) | |

| Length of stay, post-surgery | 13 (9–20) | 13 (9–18) | 18 (12–29) | < 0.001 |

| Cumulated Ambulation Score =6 b | 342 (77) | 302 (88) | 40 (12) | < 0.001 |

| Cumulated Ambulation Score <6 | 102 (23) | 71 (70) | 31 (30) | |

Includes 12 subtrochanteric fractures.

A score of 6 equals independent basic mobility status on hospital discharge.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier graph of 1-year (grey vertical line) and 5-year post-surgical survival of patients independent in basic mobility (CAS =6, blue line) and not (CAS <6, red line) on acute hospital discharge.

Adjusted Cox regression analysis showed that the likelihood of not surviving the first post-surgery year was 2 times higher for men and those with CAS <6, while the corresponding 5-year likelihoods were 1.5 times higher for those with a CAS <6 and for men; 2 times higher for those 80 years or older; increased by 50% per point higher ASA grade; and was reduced by 11% per point higher New Mobility Score, when adjusted for the cognitive and fracture type status (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis of risk factors of mortality within 1 and 5 years after hip fracture surgery, n = 444

| 1-year adjusted | 5-year adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

| 60–69 years of age | Reference | |||

| 70–79 years of age | 1.1 (0.4–3.3) | 0.8 | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) | 0.6 |

| 80–89 years of age | 1.9 (0.7–4.9) | 0.2 | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | 0.02 |

| 90 years and older | 1.5 (0.5–4.5) | 0.4 | 2.1 (1.2–3.7) | 0.01 |

| Women | Reference | |||

| Men | 2.1 (1.3–3.6) | 0.005 | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 0.01 |

| NMS 2–9 (continuous) a | 0.87 (0.77–0.97) | 0.01 | 0.89 (0.84–0.94) | < 0.001 |

| High cognitive status | Reference | |||

| Low cognitive status | 0.93 (0.53–1.6) | 0.8 | 0.94 (0.69–1.3) | 0.7 |

| ASA grade 1–4 (continuous) | 1.5 (0.98–2.3) | 0.07 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | < 0.001 |

| Femoral neck fracture | Reference | |||

| Trochanteric fractureb | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 0.4 | 0.97 (0.74–1.3) | 0.8 |

| Cumulated Ambulation Score =6c | Reference | |||

| Cumulated Ambulation Score <6 | 1.8 (1.1–3.2) | 0.04 | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 0.03 |

NMS: New Mobility Score, high scores indicate high pre-fracture functional level.

Includes 12 subtrochanteric fractures.

A score of 6 equals independent basic mobility status on hospital discharge.

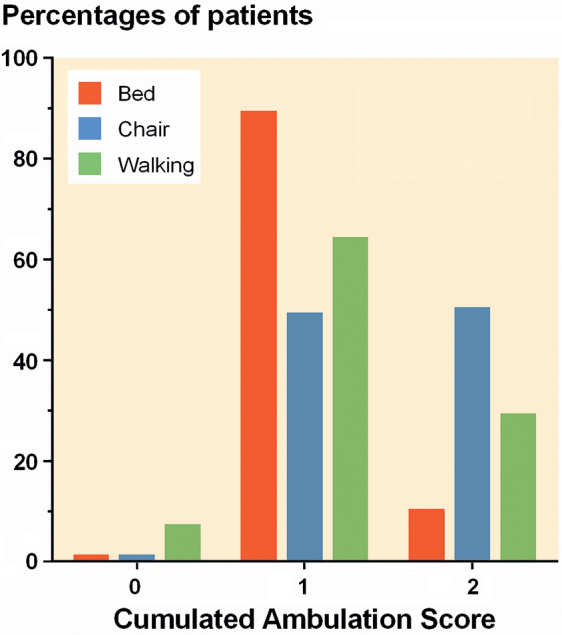

Basic mobility activities

Subgroup analysis showed that only 1 of the 102 non-independent patients was completely bedridden upon hospital discharge, but that 92 (90%) were non-independent in the CAS activity getting in and out of bed, while this was the case for 50% and 71%, respectively, for the sit-to-stand-to-sit and walking activity (Figure 2). Furthermore, the 1-year survival decreased (HR =0.57, CI 0.37–0.88) with lower CAS points (0–5 points). Corresponding 5-year data were (HR =0.37, CI 0.21–0.67).

Figure 2.

Distribution of CAS scores: 0 = cannot, 1 = can with assistance/guiding, and 2 = can independent of human assistance for each of the 3 CAS activities, at time of hospital discharge, for the 102 patients not reaching independence in the total CAS =6 points.

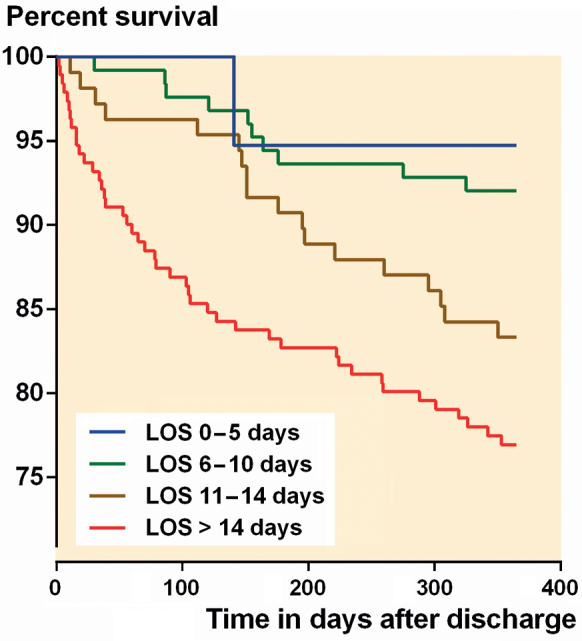

Influence of LOS on post-discharge mortality rates

73 patients (16%) died within the first year following discharge, and the risk of death increased by 1.5% per day longer in hospital (HR =1.015, CI 1.01–1.02) as illustrated by 5% 1-year deaths in patients with LOS from 0–5 days, 8% in the 6–10 days group, 17% in the 11–14 days group, and 23% of patients with LOS >14 days (Figure 3), and confirmed by the log-rank survival distribution test: x2(3) = 14.9 (p = 0.002).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier graph of 1-year post-discharge survival of patients according to post-surgery length of hospital stay (LOS).

Discussion

We found that the basic mobility status on acute hospital discharge, evaluated with the reliable and validated CAS score, was associated with long-term mortality rates in patients with hip fracture when adjusted for important pre-surgery variables. We also found that the basic mobility activity, getting in and out of bed, was the most compromised, and that mortality rates and LOS had a direct relationship. The patients studied (60 years or older at the time of the fracture, pre-fracture ambulatory, and residing in their own home) followed a multidisciplinary in-hospital enhanced recovery program. Nevertheless, although we focused our study on the patients considered to have the best potential for leaving hospital with an independent basic mobility status, this was not reached for almost 25% of our patients and was associated with the death of more than 75% after 5 years.

Basic mobility status

The importance of the ambulatory status early after surgery we found corresponds well to that reported from other countries (Gdalevich et al. 2004, Siu et al. 2006, Panula et al. 2009, Dubljanin-Raspopovic et al. 2013, Iosifidis et al. 2016), with the same 1-year or longer follow-up. However, none based their ambulatory variable on a combined score where independence was only reached if independent in a combination of bed, chair, and walking activities as evaluated with the CAS. This seems important, as our subgroup analysis revealed that some patients classified as non-independent actually were able to get up from a chair (50% of patients) and maybe also to walk (29%) independently, but not able to get in and out of bed without some level of personal assistance (90%).

Nonetheless, the overall questions are: why do some patients not reach an independent ambulatory level, and what can possibly be done to further enhance the perioperative multidisciplinary program?

We know that the post-surgery ambulatory status following HF is influenced by e.g. age, pre-fracture function, fracture type, anemia, hip fracture-related pain, muscle strength, and fear of falling (Kristensen 2011), in addition to the ability to complete planned physical therapy on the first post-surgery day (Hulsbaek et al. 2015), and associated with short-term mortality (Foss et al. 2006). Further, a recent study provides knowledge of patient-reported factors limiting the basic mobility status and ability to complete planned physical therapy early after HF surgery, with fatigue and hip fracture-related pain the most frequent reported reasons (Munter et al. 2017). Correspondingly, fatigue and pain were significantly related to functional ability 3 months post-discharge hip fracture rehabilitation (Folden and Tappen 2007).

Handling hip fracture-related pain is already a strong in-hospital focus area, but still not perfectly handled during acute hospitalization, and especially for patients with a trochanteric fracture (Kristensen 2011). On the contrary, monitoring and specific interventions towards reducing fatigue or fear of falling are commonly not part of today’s hip fracture programs and sparsely studied in this patient group. Also, it might be that continuation of the more intensive physiotherapy program throughout the entire admittance could have reduced the number of non-independent patients at the time of discharge.

Other variables

In addition to the basic mobility CAS status, we also found that men, and those with a lower pre-fracture functional level, were more likely to die within both time-points, compared with women, and those with a better functional status. Further, the risk of 5-year deaths was increased by 50% per 1 point higher ASA grade, and for those 80 years or older compared with those in their sixties. Our findings thereby add to the evidence (Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014) of the 4 variables mentioned earlier as strong pre-surgery predictors of mortality following HF. However, in significant contrast to the 2 recent reviews (Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014), we found no statistical influence of the cognitive status for increased risk of mortality, probably explained by our inclusion of pre-fracture ambulatory patients without severe cognitive impairments, and no nursing home residents.

Length of stay

The influence of LOS on short- and long-term mortality after the HF has been extensively discussed within the last few years (Nordstrom et al. 2015, Nikkel et al. 2015, Sheehan et al. 2016), and to some extent focused on the general reduction in LOS. We found that each day of increase in LOS was associated with a 3% increased odds of death during the first post-surgery year. Our finding of mortality associated with longer LOS is in accordance with data from New York state (Nikkel et al. 2015), but in contrast to that reported from Sweden (Nordstrom et al. 2015). However, caution is needed when interpreting and comparing LOS after hip fracture surgery, as this is strongly influenced by the discharge destination, the fulfillment of functional discharge criteria, and whether nursing home residents (commonly discharged back to their home a few days after surgery) are included in the analysis.

Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths are that all patients were followed for 5 years post-surgery; deaths were verified by the national civil registry; we studied only patients with pre-fracture independent walking status, and who followed the same enhanced hip fracture program. A weakness is that we did not include other post-surgery variables (e.g. medical complications), beyond the post-surgery basic mobility status, in our long-term mortality analysis. However, we wished to examine the influence of the modifiable post-surgery basic mobility status only, when adjusted for well-established pre-surgery factors (Hu et al. 2012, Smith et al. 2014). Other weaknesses may be that a specific co-morbidity measurement was not evaluated as a confounder, and that we have no post-discharge rehabilitation data. In summary, we found increased 1- and 5-year mortality rates for HF patients with pre-fracture independent mobility but without independent basic mobility status on hospital discharge. We also found that longer LOS was associated with higher mortality rates. Further studies, focused on whether early interventions that improve the basic mobility status of patients with HF also decrease mortality rates, should be instigated.

MTK collected the materials, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft. HK contributed to interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript.

We thank the Physical Therapy staff for their valuable contribution to daily monitoring and registration of the progress in basic mobility of the patients, using the CAS score.

Acta thanks Max Gordon and Lena Zidén for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Dubljanin-Raspopovic E, Markovic-Denic L, Marinkovic J, Nedeljkovic U, Bumbasirevic M.. Does early functional outcome predict 1-year mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (8): 2703–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folden S, Tappen R.. Factors influencing function and recovery following hip repair surgery. Orthop Nurs 2007; 26 (4): 234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss N B, Kristensen M T, Kehlet H.. Prediction of postoperative morbidity, mortality and rehabilitation in hip fracture patients: The cumulated ambulation score. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20 (8): 701–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K M, Hawkes W G, Hebel J R, Felsenthal G, Clark M, Zimmerman S I, Kenzora J E, Magaziner J.. Mobility after hip fracture predicts health outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46 (2): 169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdalevich M, Cohen D, Yosef D, Tauber C.. Morbidity and mortality after hip fracture: The impact of operative delay. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124 (5): 334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig H, Rubenstein L V, Sloane R, Horner R, Kahn K.. What is the role of timing in the surgical and rehabilitative care of community-dwelling older persons with acute hip fracture? Arch Intern Med 1997; 157 (5): 513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y.. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2012; 43 (6): 676–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsbaek S, Larsen R F, Troelsen A.. Predictors of not regaining basic mobility after hip fracture surgery. Disabil Rehabil 2015; 37 (19): 1739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosifidis M, Iliopoulos E, Panagiotou A, Apostolidis K, Traios S, Giantsis G.. Walking ability before and after a hip fracture in elderly predict greater long-term survivorship. J Orthop Sci 2016; 21 (1): 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen M T. Factors affecting functional prognosis of patients with hip fracture. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 47 (2): 257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen M T, Kehlet H.. Most patients regain prefracture basic mobility after hip fracture surgery in a fast-track programme. Dan Med J 2012; 59 (6): A4447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen M T, Andersen L, Bech-Jensen R, Moos M, Hovmand B, Ekdahl C, Kehlet H.. High intertester reliability of the cumulated ambulation score for the evaluation of basic mobility in patients with hip fracture. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23 (12): 1116–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen M T, Foss N B, Ekdahl C, Kehlet H.. Prefracture functional level evaluated by the New Mobility Score predicts in-hospital outcome after hip fracture surgery. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (3): 296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munter K H, Clemmesen C G, Foss N B, Palm H, Kristensen M T.. Fatigue and pain limit independent mobility and physiotherapy after hip fracture surgery. Disabil Rehabil 2017; 1–9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikkel L E, Kates S L, Schreck M, Maceroli M, Mahmood B, Elfar J C.. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and risk of early mortality after discharge in New York state: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2015; 351: h6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom P, Gustafson Y, Michaelsson K, Nordstrom A.. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and short term risk of death after discharge: A total cohort study in Sweden. BMJ 2015; 350: h696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panula J, Pihlajamaki H, Savela M, Jaatinen P T, Vahlberg T, Aarnio P, Kivela S L.. Cervical hip fracture in a Finnish population: Incidence and mortality. Scand J Surg 2009; 98 (3): 180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli P, Metozzi A, Benvenuti E, Bonamassa L, Brandi G, Cavalli L, Colli E, Fossi C, Parri S, Giolli L, Tanini A, Fasano A, Di T G, Brandi M L.. Connections between the outcomes of osteoporotic hip fractures and depression, delirium or dementia in elderly patients: Rationale and preliminary data from the CODE study. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2012; 9 (1): 40–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan K J, Sobolev B, Chudyk A, Stephens T, Guy P.. Patient and system factors of mortality after hip fracture: A scoping review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17: 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu A L, Penrod J D, Boockvar K S, Koval K, Strauss E, Morrison R S.. Early ambulation after hip fracture: Effects on function and mortality. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166 (7): 766–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, Ong A, Myint P K.. Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2014; 43 (4): 464–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraldsen K, Sletvold O, Thingstad P, Saltvedt I, Granat M H, Lydersen S, Helbostad J L.. Physical behavior and function early after hip fracture surgery in patients receiving comprehensive geriatric care or orthopedic care: A randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014; 69 (3): 338–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]