Abstract

Background and purpose

The role of pelvic incidence in hip disorders is unclear. Therefore, we undertook a literature review to evaluate the evidence on that role.

Methods

A search was carried out on MEDLINE, SCOPUS, CENTRAL, and CINAHL databases. Quantitative analysis was based on comparison with a reference population of asymptomatic subjects.

Results

The search resulted in 326 records: 15 studies were analyzed qualitatively and 13 quantitatively. The estimates of pelvic incidence varied more than 10 degrees from 47 (SD 3.7) to 59 (SD 14). 2 studies concluded that higher pelvic incidence might contribute to the development of coxarthrosis while 1 study reported the opposite findings. In 2 studies, lower pelvic incidence was associated with a mixed type of femoroacetabular impingement. We formed a reference population from asymptomatic groups used or cited in the selected studies. The reference comprised 777 persons with pooled average pelvic incidence of 53 (SD 10) degrees. The estimate showed a relatively narrow 95% CI of 52 to 54 degrees. The 95% CIs of only 4 studies did not overlap the CIs of reference: 2 studies on coxarthrosis, 1 on mixed femoroacetabular impingement, and 1 on ankylosing spondylitis

Interpretation

We found no strong evidence that pelvic incidence plays any substantial role in hip disorders. Lower pelvic incidence may be associated with the mixed type of femoroacetabular impingement and hip problems amongst patients with ankylosing spondylitis. The evidence on association between pelvic incidence and coxarthrosis remained inconclusive.

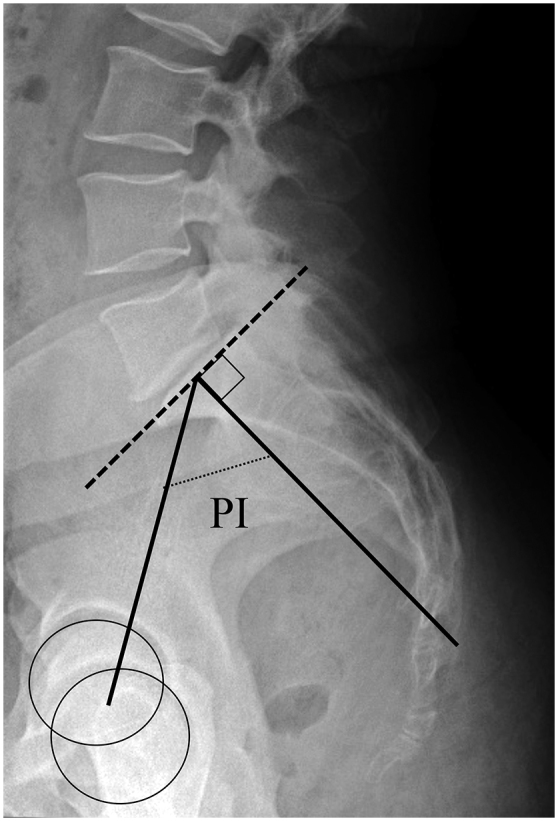

Pelvic incidence is an individual and unchangeable measure that describes pelvic anatomy independently of the position of the pelvis (Duval-Beaupere et al. 1992, Legaye et al. 1998). It is defined as the angle between the line perpendicular to the sacral plate at its midpoint and the line connecting this point to the center of the axis of the femoral heads (Legaye et al. 1998) (Figure 1). The pelvic incidence becomes stabilized around the age of 10 years (Mangione et al. 1997) varying widely from 33 to 85 degrees (Vaz et al. 2002). For more than 30 years, it has been thought that pelvic incidence may be related to certain spinal disorders (Offierski and MacNab 1983, Barrey et al. 2007, Chaleat-Valayer et al. 2011, Wang et al. 2014) and, sometimes, both back pain and pelvic incidence have been described as altered after a hip replacement (Ben-Galim et al. 2007, Parvizi et al. 2010, Eyvazov et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Measurement of pelvic incidence

The role of pelvic incidence in hip disorders has been studied less. There have been no comprehensive systematic reviews conducted on the topic so far. The reports on that role have been inconsistent, suggesting that either such a role does not exist (Weng et al. 2016, Ochi et al. 2017) or that higher pelvic incidence may predispose or be otherwise connected to coxarthrosis (Yoshimoto et al. 2005, Bredow et al. 2015, Ochi et al. 2017). The evidence has been controversial. It has been suggested that higher pelvic incidence might contribute to the development of hip osteoarthrosis, as individuals with increased pelvic incidence tend to lose the anterior covering of the acetabulum due to excessive pelvic tilt with aging (Yoshimoto et al. 2005). Additionally, hip osteoarthrosis may probably be triggered by damage to the cartilage or labrum caused by femoroacetabular impingement, which is related, in turn, to abnormal pelvic incidence (Beck et al. 2005). Gebhart et al. (2016) studied cadaveric specimens and reported a significant correlation between higher pelvic incidence and hip osteoarthrosis-while no such connection was found by Raphael et al. (2016) when analyzing computed tomography of patients with hip disorders. Even fewer studies have been conducted on the significance of pelvic incidence in hip pathologies other than coxarthrosis. It has been suggested that pelvic incidence may play some role in hip disorders associated with ankylosing spondylitis, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), and subchondral insufficiency fractures (Gao et al. 2015, Gu et al. 2015, Jo et al. 2016, Hellman et al. 2017). In 2 recent systematic reviews (Pierannunzii 2017, Riviere et al. 2017) on femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), lower pelvic incidence has been suggested to relate to a mixed type of impingement. The correlation between anterior pelvic tilt and lower pelvic incidence and FAI occurrence has been considered so important that Riviere et al. (2017) even suggested a classification of spinopelvic parameters as risk factors of developing FAI.

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the evidence on the connection between pelvic incidence and hip disorders.

Methods

PICO

The criteria for considering studies for this review were based on the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) framework as follows:

Adults with hip disorders excluding malignancy and acute trauma. Observational and clinical studies published in peer-reviewed journals excluding theses, conference proceedings, and guidelines. No restrictions based on the time of publication or language. Abstract available.

Intervention—not applicable.

Comparison—not applicable.

Outcome—primary: risk ratios or odds ratios; secondary—any outcome.

Data sources and searches

The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (via PubMed), CINAHL, and SCOPUS databases were searched in February 2017. The search clauses are presented in Table 1 (see Supplementary data). The references of identified articles and reviews were also checked for relevancy.

Study selection

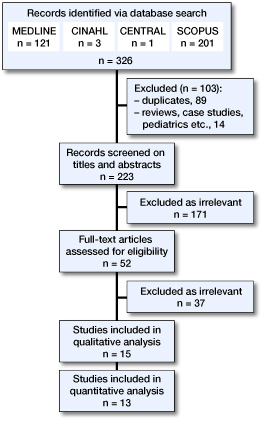

2 independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts of articles and assessed full texts of potentially relevant studies (Figure 2). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer. The methodological quality of the included trials was not rated.

Figure 2.

Search and data extraction flow. No additional records were identified from reference lists.

Data extraction

The ultimate goal of the review was to evaluate the available evidence on the topic quantitatively. Therefore, when extracting data, some records were omitted due to inability to provide the statistics needed for analysis or as being subsets of the same study. For example, a study was excluded if pelvic incidence average figures were not reported. The data needed for a quantitative analysis were extracted from the included trials using a standardized form based on recommendations by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 Edition, part 7.6.9 (Higgins and Green 2011).

Statistics

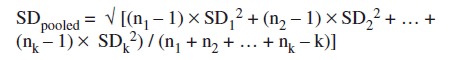

When not reported, a standard deviation (SD) was calculated from a range as:

Pooled average estimates (M) of several studies were calculated without weighting the studies according to their variance. Pooled SDs of several studies were calculated as (“n”—sample size):

|

The 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated as:

All the calculations were made using Microsoft® Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). The study protocol is available on request from the corresponding author.

Funding and potential conflicts of interest

No funding was received and no conflicts of interest are declared.

Results

The search resulted in 326 records, of which 223 were screened based on their titles and abstracts, and 52 based on their full texts (Table 2, see Supplementary data and Figure 2). 15 studies were analyzed qualitatively in more detail. After excluding 2 studies, the final sample for the quantitative analysis comprised 13 studies (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

All of the 15 studies were published within the last 8 years. Most of the included studies were retrospective. 10 studies targeted patients with coxarthrosis, 2 studies—patients with ankylosing spondylitis, 2 studies—patients with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), and 1 study was focused on subchondral insufficiency fractures. Reference groups were used in 7 studies: 6 reference samples were drawn out of a healthy population (of these, 1 sample was matched) and 1 control group consisted of patients with low back pain. Among the studies, 6 were cross-sectional while the rest assessed spinopelvic parameters before and after hip total replacement. Lateral standing radiography was used in all studies, except for 1 (Weinberg et al. 2016a). In addition, some of the included studies employed a 3D reconstruction technique, sitting radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were considered appropriate and clearly defined in all studies except for one (Gu et al. 2015).

The sample sizes of the included studies varied from 19 to 150 patients (Table 3, see Supplementary data). As expected, the patients with coxarthrosis and subchondral insufficiency fractures were older (around 60 years or older) than patients with ankylosing spondylitis or femoroacetabular impingement (< 40 years). Across the samples, there was a slight predomination of women. The estimates of pelvic incidence varied more than 10 degrees from 47 (SD 4) to 59 (SD 14). The authors of a few studies concluded that pelvic incidence might play some role in hip disorders, even though the sample sizes were considered underpowered to detect statistically significant results. 2 studies concluded that higher pelvic incidence might contribute to the development of coxarthrosis (Yoshimoto et al. 2005, Bredow et al. 2015). Conversely, 1 study (Weng et al. 2015) reported that pelvic incidence might not be involved in coxarthrosis. Gao et al. (2015) reported that pelvic incidence might be correlated with life quality, body pain, “vitality,” and “emotional role” in patients with ankylosing spondylitis when comparing the data gathered before and after hip replacement. Hellman et al. (2017) stated that pelvic incidence in patients with femoroacetabular impingement was lower than in the general population—49 (SD 12) versus 55 (SD 11), respectively. Weinberg et al. (2016a) specified further that this effect only exists in the Cam type of femoroacetabular impingement.

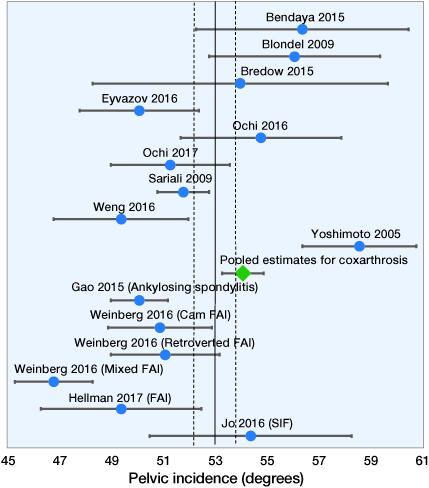

To form a reference population of asymptomatic individuals for this review, “healthy” groups used in the included studies along with the reports cited by them were pooled (Legaye et al. 1998, Roussouly et al. 2005, Vialle et al. 2005, Legaye 2009, Sariali et al. 2009, Weng et al. 2015, Jo et al. 2016, Weinberg et al. 2016a). In this way, the reference “healthy” sample comprised 777 persons (Table 4, see Supplementary data, and Figure 3). Their sex was equally distributed and they were younger (39 (SD 11) years) than their symptomatic counterparts, except for the studies on ankylosing spondylitis and femoroacetabular impingement. Within this asymptomatic group, the pooled average estimate of pelvic incidence was 53 (SD 10) degrees. The estimate showed a relatively narrow 95% CI of 52 to 54 degrees. For the subpopulation of patients with coxarthrosis (pooled n = 602 subjects), the pooled mean estimate of pelvic incidence was 54 (SD 11) degrees with 95% CI 53 to 55 degrees overlapping the 95% CI of the estimate pooled from an asymptomatic population. Figure 3 presents these findings in the form of a forest plot. From this figure, it can be noticed that CIs of only 4 studies did not overlap the 95% CI calculated for an asymptomatic population: 2 studies on coxarthrosis (Yoshimoto et al. 2005, Weng et al. 2015), 1 on mixed femoroacetabular impingement (Weinberg et al. 2016a), and 1 on ankylosing spondylitis (Gao et al. 2015).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of pelvic incidence estimates reported by the included studies and their pooled figures along with those for an asymptomatic population.Solid line delineates the pooled average estimate of pelvic incidence in an asymptomatic population. Dashed lines demarcate the 95% confidence interval of that estimate. Diamond shape represents the pooled estimate of pelvic incidence in patients with coxarthrosis. First-named author only cited.

Discussion

This systematic review did not find evidence that pelvic incidence would play any substantial role in hip disorders. However, the results suggested that lower pelvic incidence might be associated with femoroacetabular impingement (at least its mixed type) and with hip problems associated with ankylosing spondylitis. The evidence on association between pelvic incidence and coxarthrosis remained inconclusive.

The main weakness of this review lies in the weaknesses and the scope of the included studies. Most of the studies were retrospective and underpowered. Only a few studies focused on pelvic incidence as a main target. For the rest, pelvic incidence was only a secondary outcome or part of spinopelvic sagittal alignment totality. The study designs, reference groups, settings, and methods varied widely, leading to incapability to perform a true meta-analysis or to analyze systematically the methodological quality of the studies. We did not conduct a meta-synthesis and therefore the degree of heterogeneity between the included trials remains unknown. Our quantitative analysis should be generalized with caution—rather as an uncertain predisposition than as an exact recommendation. Despite these weaknesses, this systematic review provides valuable knowledge on the topic of interest both qualitatively and quantitatively. The results should be noted when screening for the risk factors of hip disorders, planning surgery, or predicting the course of these conditions.

This is the first systematic review focused entirely on the importance of only one single spinopelvic parameter—pelvic incidence—amongst patients with different hip problems. Therefore, the results are not directly comparable with any previous reports. The diversity and inconsistency of evidence on the topic may reflect the fact that, while the significance of pelvic incidence in different disorders has been proposed for 3 decades, most research on the subject is just beginning. Indeed, 12 of 15 included studies have been conducted very recently, in a narrow 2-year timeframe. Thus, one might expect more data on the matter to appear in the few next years, which may soon require a review update.

The interpretation of the results is especially difficult as there is no agreement on “normal” reference values for pelvic incidence (Vaz et al. 2002). It has even been suggested that such values may not be settable as there is also a high variance of pelvic incidence estimates amongst healthy subjects (Vrtovec et al. 2012). However, this doubt is not in line with probably the largest report on pelvic incidence measurement conducted on 880 cadaveric specimens (Weinberg et al. 2016b), which showed no barrier to creating reference values of pelvic incidence. Nevertheless, reference values are so far waiting to be created in a large population-based study on the topic.

According to this review, of all existing hip disorders, only 4 had been studied regarding the topic so far. As most included studies were conducted amongst patients with coxarthrosis, many questions are left for research. For example, the association between pelvic incidence and osteoporotic or other fractures in spinopelvic area is unclear.

The scope of this review was limited only to pelvic incidence. Pelvic posture and kinematics connected to spinal balance might play a more relevant role in hip disorders than pelvic incidence. There might be a connection between femoroacetabular impingement and low pelvic incidence. The pathogenesis and the exact definition of the mixed type of femoroacetabular impingement are unclear and femoroacetabular impingement often demonstrates anatomical features of both cam and pincer types (Ganz et al. 2003, 2008). This fact adds uncertainty concerning the association between the mixed type of femoroacetabular impingement and pelvic incidence.

In summary, we found no evidence that pelvic incidence plays any substantial role in hip disorders. Lower pelvic incidence may be associated with the mixed type of femoroacetabular impingement and hip problems amongst patients with ankylosing spondylitis. The evidence on association between pelvic incidence and coxarthrosis remained inconclusive.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Tables 1–4 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1377017

References

- Barrey C, Jund J, Noseda O, Roussouly P.. Sagittal balance of the pelvis–spine complex and lumbar degenerative diseases: A comparative study about 85 cases. Eur Spine J 2007. 16 (9): 1459–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz. R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: Femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87 (7): 1012–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N, Haim A, Hipp J, Dekel S, Floman Y.. Hip–spine syndrome: The effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32 (19): 2099–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendaya S, Lazennec J Y, Anglin C, Allena R, Sellam N, Thoumie P, Skalli W.. Healthy vs. osteoarthritic hips: A comparison of hip, pelvis and femoral parameters and relationships using the EOS® system. Clin Biomech 2015; 30 (2): 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel B, Parratte S, Tropiano P, Pauly V, Aubaniac J M, Argenson J N.. Pelvic tilt measurement before and after total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009; 95 (8): 568–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredow J, Katinakis F, Schlüter-Brust K, Krug B, Pfau D, Eysel P, Dargel J, Wegmann K.. Influence of hip replacement on sagittal alignment of the lumbar spine: An EOS study. Technology and Health Care 2015; 23 (6): 847–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaleat-Valayer E, Mac-Thiong J M, Paquet J, Berthonnaud E, Siani F, Roussouly P.. Sagittal spino-pelvic alignment in chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2011; 20 (Suppl 5): 634–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval-Beaupere G, Schmidt C, Cosson P A.. Barycentremetric study of the sagittal shape of spine and pelvis: The conditions required for an economic standing position Ann Biomed Eng 1992; 20 (4): 451–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyvazov K, Eyvazov B, Basar S, Nasto L A, Kanatli U.. Effects of total hip arthroplasty on spinal sagittal alignment and static balance: A prospective study on 28 patients. European Spine J 2016; 25 (11): 3615–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Notzli H, Siebenrock K A.. Femoroacetabular impingement: A cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (417): 112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris W H.. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: An integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (2): 264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wang B, Xie Z K, Shen P F, Xu J D, Zheng C, Qu Y X.. Total hip arthroplasty for ankylosing spondylitis: The spine-pelvis sagittal balance and quality of life. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research 2015; 19 (4): 516–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart J J, Weinberg D S, Bohl M S, Liu R W.. Relationship between pelvic incidence and osteoarthritis of the hip. Bone Joint Res 2016; 5 (2): 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Zhang Z, Kang Y, Sheng P, Yang Z, Zhang Z, Liao W.. Roles of sagittal anatomical parameters of the pelvis in primary total hip replacement for patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (12): 2219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellman M D, Haughom B D, Brown N M, Fillingham Y A, Philippon M J, Nho S J.. Femoroacetabular impingement and pelvic incidence: Radiographic comparison to an asymptomatic control. Arthroscopy 2017; 33(3): 545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 510 [updated March 2011]. 2011. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- Jo W L, Lee W S, Chae D S, Yang I H, Lee K M, Koo K H.. Decreased lumbar lordosis and deficient acetabular coverage are risk factors for subchondral insufficiency fracture. J Korean Medical Science 2016; 31 (10): 1650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legaye J. Influence of the sagittal balance of the spine on the anterior pelvic plane and on the acetabular orientation. Int Orthop 2009; 33 (6): 1695–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legaye J, Duval-Beaupere G, Hecquet J, Marty C.. Pelvic incidence: A fundamental pelvic parameter for three-dimensional regulation of spinal sagittal curves. Eur Spine J 1998; 7 (2): 99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione P, Gomez D, Senegas J.. Study of the course of the incidence angle during growth. Eur Spine J 1997; 6 (3): 163–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi H, Baba T, Homma Y, Matsumoto M, Nojiri H, Kaneko K.. Importance of the spinopelvic factors on the pelvic inclination from standing to sitting before total hip arthroplasty. Eur Spine J 2016; 25 (11): 3699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi H, Homma Y, Baba T, Nojiri H, Matsumoto M, Kaneko K.. Sagittal spinopelvic alignment predicts hip function after total hip arthroplasty. Gait Posture 2017; 52: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offierski C M, MacNab I.. Hip-spine syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983; 8 (3): 316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Pour A E, Hillibrand A, Goldberg G, Sharkey P F, Rothman R H.. Back pain and total hip arthroplasty: A prospective natural history study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (5): 1325–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierannunzii L. Pelvic posture and kinematics in femoroacetabular impingement: A systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael I J, Kepler C K, Restrepo S, Radcliff K E, Rasouli M R, Albert T J.. Pelvic incidence in patients with hip osteoarthritis. Arch Bone Joint Surg 2016; 4 (2): 132–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere C, Hardijzer A, Lazennec J Y, Beaule P, Muirhead-Allwood S, Cobb J.. Spine-hip relations add understandings to the pathophysiology of femoro-acetabular impingement: A systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017; 103(4): 549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J.. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005; 30 (3): 346–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sariali E, Lazennec J Y, Khiami F, Gorin M, Catonne Y.. Modification of pelvic orientation after total hip replacement in primary osteoarthritis. Hip International 2009; 19 (3): 257–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang B, Yin B, Liu W, Yang F, Lv G.. The relationship between spinopelvic parameters and clinical symptoms of severe isthmic spondylolisthesis: A prospective study of 64 patients. Eur Spine J 2014; 23 (3): 560–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz G, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J.. Sagittal morphology and equilibrium of pelvis and spine. Eur Spine J 2002; 11 (1): 80–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg D S, Gebhart J J, Liu R W, Salata M J.. Radiographic signs of femoroacetabular impingement are associated with decreased pelvic incidence arthroscopy. J Arthroscopic and Related Surgery 2016a; 32 (5): 806–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg D S, Morris W Z, Gebhart J J, Liu R W.. Pelvic incidence: An anatomic investigation of 880 cadaveric specimens. Eur Spine J 2016b; 25 (11): 3589–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng W J, Wang W J, Wu M D, Xu Z H, Xu L L, Qiu Y.. Characteristics of sagittal spine-pelvis-leg alignment in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis. Eur Spine J 2015; 24 (6): 1228–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng W, Wu H, Wu M, Zhu Y, Qiu Y, Wang W.. The effect of total hip arthroplasty on sagittal spinal-pelvic-leg alignment and low back pain in patients with severe hip osteoarthritis. Eur Spine J 2016; 25 (11): 3608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P.. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (2): 260–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrtovec T, Janssen M M, Pernus F, Castelein R M, Viergever M A.. Analysis of pelvic incidence from 3-dimensional images of a normal population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012; 37 (8): E479–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto H, Sato S, Masuda T, Kanno T, Shundo M, Hyakumachi T, Yanagibashi Y.. Spinopelvic alignment in patients with osteoarthrosis of the hip: A radiographic comparison to patients with low back pain. Spine 2005; 30 (14): 1650–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.