Abstract

Background and purpose

The incidence of orthopedic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections is increasing. Vancomycin may therefore play an increasingly important role in orthopedic perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis. Studies investigating perioperative bone and soft tissue concentrations of vancomycin are sparse and challenged by a lack of appropriate methods. We assessed single-dose plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue (SCT) and bone concentrations of vancomycin using microdialysis in male patients undergoing total knee replacement.

Methods

1,000 mg of vancomycin was administered postoperatively intravenously over 100 minutes to 10 male patients undergoing primary total knee replacement. Vancomycin concentrations in plasma, SCT, cancellous, and cortical bone were measured over the following 8 hours. Microdialysis was applied for sampling in solid tissues.

Results

For all solid tissues, tissue penetration of vancomycin was significantly impaired. The time to a mean clinically relevant minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2 mg/L was 3, 36, 27, and 110 min for plasma, SCT, cancellous, and cortical bone, respectively. As opposed to the other compartments, a mean MIC of 4 mg/L could not be reached in cortical bone. The area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to the last measured value and peak drug concentrations (Cmax) for SCT, cancellous, and cortical bone was lower than that of free plasma. The time to Cmax was higher for all tissues compared with free plasma.

Interpretation

Postoperative penetration of vancomycin to bone and SCT was impaired and delayed in male patients undergoing total knee replacement surgery. Adequate perioperative vancomycin concentrations may not be reached using standard prophylactic dosage.

The objective of antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery is to lower the microbial load of intraoperative contamination to a level that host defenses can overcome (Mangram et al. 1999). Though specific antimicrobial target concentrations for this task are not established, it is advocated that not only plasma but also tissue concentrations should, at least, exceed minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of potential antimicrobial pathogens throughout surgery (Whiteside 2016). Traditionally, plasma concentrations of antimicrobials have been considered to reflect tissue concentrations. Recently, however, a number of studies have indicated that this may not always be true (Joukhadar et al. 2001, Barbour et al. 2009). Consequently, surgical antimicrobial dosing regimens based on plasma pharmacokinetics, i.e. the fate of drug in plasma, may result in insufficient perioperative tissue concentrations.

Determination of antimicrobial tissue concentrations is challenging. Various methodological approaches have been employed, but all seem to suffer from important methodological limitations (Mouton et al. 2008, Landersdorfer et al. 2009, Pea 2009). Particularly for bone, no ideal method has been established. Recently, the pharmacokinetic tool microdialysis (MD) has been shown to be useful for sampling various antimicrobials in drill holes in bone (Stolle et al. 2004, Schintler et al. 2009, Traunmuller et al. 2010a, Tottrup et al. 2014, Bue et al. 2015, Tottrup et al. 2015, Hanberg et al. 2016). In the context of orthopedic antimicrobial surgical prophylaxis, measurements obtained by means of MD seem relevant, and reflective of the true perioperative situation.

The most frequent cause of orthopedic infections is Staphylococcus aureus and the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections is increasing (Murillo et al. 2015, Benito et al. 2016). Vancomycin remains one of the few drugs effective against these bacteria and is recommended as first-line choice in the treatment of orthopedic MRSA infections (Lew and Waldvogel 2004, Trampuz and Widmer 2006). In the years to come, vancomycin may therefore become the first choice for perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis in some orthopedic settings. So far, vancomycin bone concentrations have only been assessed using the bone biopsy approach (Kitzes-Cohen et al. 2000, Vuorisalo et al. 2000, Landersdorfer et al. 2009). The rather large variation in tissue concentrations in these studies may be related to methodological challenges. In a recent pig study, we have successfully employed MD for measurement of vancomycin in drill holes in healthy cancellous and cortical bone and found incomplete and delayed bone penetration (Bue et al. 2015). If this is also the case in the clinical setting, perioperative tissue concentrations may be inadequate for optimal prevention of infection. We therefore assessed single-dose plasma, SCT, and bone concentrations of vancomycin using MD in male patients undergoing total knee replacement (TKR).

Material and methods

This study was conducted at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Horsens Regional Hospital, Denmark between March 2015 and January 2016. All chemical analyses were performed at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark.

Study design, patients, drug, and endpoints

Competent male patients with knee osteoarthritis were offered enrolment in the study if they were scheduled for a primary TKR. The patients were identified in the outpatient clinic by a single surgeon (OL) conducting the planned TKR. Exclusion criteria included allergy to vancomycin, on-going treatment with vancomycin, warfarin or other newer anticoagulants, and clinically reduced renal function.

10 patients were included in this study. All 10 patients completed the study. Mean (SD) weight of the patients was 97 (16) kg, giving a mean (SD) BMI of 30 (4.5), and they had a mean (SD) creatinine level on surgery day of 82 (14) µmol/L. As preoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis, all patients were given 1,500 mg of cefuroxime prior to surgery, which is the standard regimen in Denmark.

The MD probes were implanted at the respective locations during the TKR surgery. After the surgical procedures and calibration of the MD probes, 1,000 mg of vancomycin were administered intravenously in a peripheral catheter over 100 min. Sampling was conducted over 8 hours starting at the beginning of vancomycin infusion. Tissue penetration ratios and time to mean relevant minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) (1–8 mg/L) were the primary endpoints. Secondary endpoints were standard pharmacokinetic parameters; the area under the concentration-time curves (AUC0–last), peak drug concentration (Cmax), and time to Cmax (Tmax).

Surgery

At the end of TKR surgery, MD probes were placed in drill holes in cancellous bone in the medial tibial condyle and in cortical bone in the anterior margin approximately at the midpoint of the tibial diaphysis. While the medial tibial condyle was accessed via the TKR incision, a small 2 cm separate incision was used for the tibial diaphysis. The anatomical location of the cortical drill hole was chosen to ensure optimal intra cortical placement. The depths of the drill holes were aimed to be 25 mm for cancellous bone and 15 mm for cortical bone, and MD probes with membrane lengths of 20 and 10 mm were used. A new 2 mm drill was used for each patient. When drilling in cortical bone, saline was continuously applied, and drilling was ceased every few seconds to prevent heat necrosis of the bone. At both locations, the probes were tunneled approximately 2–3 cm under the skin before entering the drill holes. In addition to the bone probes, an SCT probe (20 mm membrane) was placed in the medial part of the thigh using the manufacturer’s standard introducer. To prevent displacement, all probes were fixed to the skin with single sutures. At the end of TKR surgery, a mixture of 150 mL ropivacaine (2 mg/mL), 1.5 mL toradol (30 mg/mL), and 0.75 mL adrenaline (1 mg/mL) was injected locally in the soft tissues surrounding the knee, intra-articularly, and in the posterior joint capsule of the knee as a routine part of pain management.

Microdialysis and sampling procedures

In vivo microdialysis is a probe-based technique, allowing for continuous sampling of water-soluble molecules in the interstitial space of accessible tissues (Joukhadar et al. 2001, Stolle et al. 2004, Schintler et al. 2009, Shukla et al. 2009, Traunmuller et al. 2010b, Hutschala et al. 2013). A semipermeable membrane at the tip of the probe allows for diffusion of molecules following the concentration gradient. As the probe is continuously perfused, equilibrium will never occur. Accordingly, the concentration in the dialysate will represent only a fraction of the actual concentration in the tissue. This fraction is referred to as the relative recovery (RR) and must be determined in order to estimate absolute tissue concentrations. In this study, retrodialysis by drug was applied for individual calibration of all the MD probes (Scheller and Kolb 1991). The principle of the retrodialysis method relies on the assumption that the diffusion across the semipermeable membrane is quantitatively equal in both directions. Therefore, vancomycin was added to the perfusion medium and the disappearance rate trough the membrane was taken as the RR. The RR was calculated using the following equation:

where Cdialysate is the concentration (µg/mL) in the dialysate, and Cperfusate is the concentration (µg/mL) in the perfusate.

The absolute, extracellular concentrations (µg/mL), Ctissue, were obtained by correcting for RR using the following equation:

A detailed description of MD can be found elsewhere (Muller 2002, Joukhadar and Muller 2005).

In the present study, the MD system consisted of CMA 107 precision pumps (µ-Dialysis AB, Stockholm, Sweden) and CMA 70 probes (membrane length 20 mm and 10 mm, molecular cut-off 20 kilo Daltons). After surgery, the MD probes were perfused with 0.9% NaCl containing vancomycin at a concentration of 1.25 µg/mL at a perfusion rate of 1 µL/min. After a 30-min tissue equilibration period, all catheters were individually calibrated by collecting a 60-min sample. Following calibration, the perfusate was changed to isotonic saline, and a 120-min washout period was allowed for. Vancomycin was then administered to the patient as previously described. For the first 2 hours, dialysates were harvested at 40-min intervals, and thereafter at 60-min intervals for the following 6 hours, giving a total of 9 samples in a sampling period of 8 hours. Venous blood samples were drawn from a peripheral catheter (cubital vein) in the middle of every dialysate sampling interval. Dialysates were instantly frozen on dry ice for a maximum of 10 hours, before being transferred to a –80 °C freezer until analysis. Dialysate concentrations were corrected for RR and ascribed to the midpoint of the sampling interval. Venous blood samples were stored at 5 °C for a maximum of 24 hours before being centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 minutes. Plasma aliquots were then frozen and stored at –80 °C until analysis.

Before removal of the probes, a CT scan of the drill hole in the anterior aspect of the tibia was conducted to verify that the drill had not penetrated to the bone marrow and that the probe had not been displaced.

Quantification of vancomycin concentrations

Measurement of the free concentration of vancomycin in plasma was determined with a homogeneous enzyme immunoassay- technique on the Cobas c501 platform (Roche, Switzerland) (Bue et al. 2015). The dialysate concentrations of vancomycin were quantified with Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography as previously described (Bue et al. 2015). The lower limit of quantification was defined as the lowest concentration with intra-run CV <20%, and was found to be 0.05 µg/mL.

Pharmacokinetic analysis and statistics

The pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters AUC0–last, Cmax, Tmax and terminal half-life (T1/2), were determined separately for each subject by non-compartmental analysis using the pharmacokinetic-series of commands in Stata (v. 14.1, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). The AUC0–last was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. Cmax was calculated as the maximum of all the recorded concentrations, and Tmax as the time to Cmax. T1/2 was calculated as ln(2)/λeq, where λeq,is the terminal elimination rate constant estimated by linear regression of the log concentration on time. These PK parameters were obtained in all 4 compartments from the same subject and hence a mixed model for repeated measurements was used with compartments as fixed effect and subject identification variable as a random effect. Furthermore, distinct residual variance was assumed within each compartment. The normality of the residuals was estimated using a Quantile–Quantile (QQ) plot for the residuals and the homogeneity of the residual variance was checked by plotting residuals vs. best linear unbiased prediction estimates. The normality of the estimated random effects was checked using a QQ-plot of the estimated random effects. Overall comparisons between the compartments were conducted using Wald’s test and pairwise comparisons using a t-test. The variables AUC0–last, Tmax, and T1/2 were analyzed using their log transformed data. A correction due to small sample size was handled using the Kenward–Roger approximation method. Consequently, AUC0–last, Tmax, and T1/2 values are given as medians with 95% CIs, and the pairwise comparisons were conducted on the log scale. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. No correction for multiple comparisons was applied. The tissue AUC0–last to plasma AUC0–last ratio (AUCtissue/AUCplasma) was calculated as a measure for tissue penetration. Statistical analyses were also performed using Stata. Values below the lower limit of detection were set to zero. The washout concentrations were low, and therefore not included in the analysis. Using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA), the time to mean MICs of 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/L was estimated using linear interpolation.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Central Denmark Region (registration number 1-16-02-472-14) and the Danish Health and Medicines Authority (EudraCT number 2014-000258-12). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The GCP unit at Aalborg and Aarhus University Hospitals conducted the mandatory monitoring procedures.

The work was supported by grants from the Korning Foundation, the Familien Hede Nielsen Foundation, the Scientific Foundation for Medical Doctors at Horsens Regional Hospital and the Bevica Foundation. No competing interests were declared.

Results

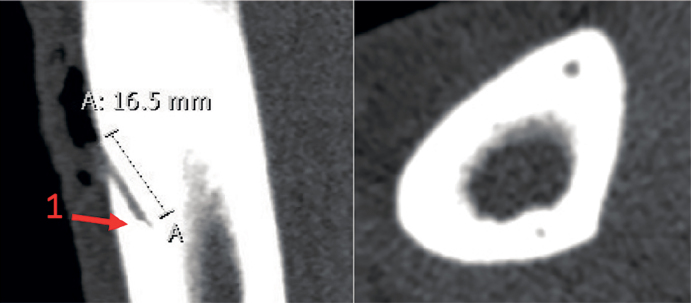

No serious adverse events or serious adverse reactions were observed. Dialysate concentrations could not be reliably determined in 2 patients, due to UHPLC apparatus failure, and their data were therefore excluded from the analysis. 2 cortical bone probes and 3 cancellous bone probes were malfunctioning, thus leaving data from 6 cortical bone locations, 5 cancellous bone locations, 8 SCT locations, and blood samples from all 10 patients. For 1 cancellous bone probe RR could not be reliably determined. Since the dialysate measurements for this probe resembled that of the other cancellous probes, RR for this probe was determined as the mean value of the remaining RR’s of the cancellous bone probes. CT- scans confirmed that all drill holes were positioned in cortical bone without communication to the bone marrow, and that all cortical bone probes were located within the drill-holes. Representative sectional views of the cortical drill hole are illustrated in Figure 1. Mean (SD) RRs were 20 (9) %, 35 (18) %, and 14 (6) % for SCT, cancellous, and cortical bone, respectively. For SCT, cancellous, and cortical bone, the mean (SD) measured concentrations in the last washout samples were 0.06 (0.07), 0.12 (0.25), and 0.10 (0.13) µg/mL, respectively.

Figure 1.

Representative sectional views of the cortical drill hole showing the position of the drill holes and the location of the cortical MD probe. 1: The gold thread within the MD probe membrane tip.

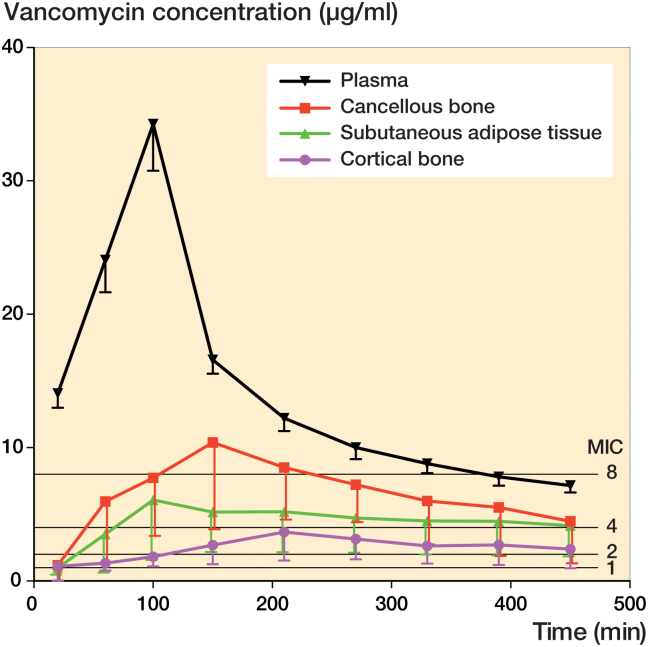

Vancomycin plasma and tissue concentration-time profiles are provided in Figure 2. Corresponding key pharmacokinetic parameters can be found in Table 1. Tissue penetration ratios (AUCtissue/AUCplasma) were below 0.5 for all solid tissues. Accordingly, AUC0–last for both bone compartments and SCT was also significantly lower than that of free plasma (p < 0.001). For the same 3 compartments, lower Cmax (p < 0.001) and higher Tmax compared with plasma were also found. Finally, AUC0–last and Cmax were lower in cortical compared with cancellous bone (p < 0.007).

Figure 2.

Mean concentration-time profiles for plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue, cancellous, and cortical bone. Bars represent 95% confidence interval. MICs of 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL are also depicted.

Table 1.

Key pharmacokinetic parameters for plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue, and cancellous and cortical bone. Values are medians (95% CI) unless otherwise stated.

| Pharmacokinetic parameter |

Plasma (unbound) |

Subcutaneous adipose tissue |

Cancellous bone |

Cortical bone |

Overall comparisona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–last (min µg/mL) | 6,296 (5,883–6,709) | 1,545 (698–2,392)c | 2,636 (1,527–3,744)c | 1,016 (661–1371)c,d | < 0.001 |

| Cmax (µg/mL)b | 34.3 (31.3–37.2) | 6.6 (3.4–9.8)c | 10.8 (6.3–15.3)c | 4.0 (2.5–5.4)c,d | < 0.001 |

| Tmax (min) | 100 (64–136) | 200 (120–281) | 148 (73–223) | 152 (81–223) | – |

| T1/2 (min) | 362 (311–414) | 583 (8–1,158) | 360 (21–700) | 392 (67–716) | 0.8 |

| AUCtissue/AUCplasma | 0.31 (0.16–0.46) | 0.45 (0.29–0.62) | 0.17 (0.11–0.24) | 0.008e |

AUC0–last = area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to the last measured value;

Cmax = peak drug concentration; Tmax = time to Cmax; T1/2 = half-life at β-phase;

AUCtissue/AUCplasma = tissue penetration expressed as the ratio of AUCtissue/AUCplasma

Overall comparison using Wald’s test for free plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue, cancellous, and cortical bone.

Values are means (95% CI).

p < 0.001 for comparison with the corresponding free plasma value.

p < 0.007 for comparison with cancellous bone.

T-test comparison of cancellous and cortical bone.

The time to mean concentrations of 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/L (MICs) are depicted in Table 2. The time to a mean MIC of 2 mg/L was 3, 36, 27, and 110 min for plasma, SCT, cancellous, and cortical bone, respectively. A mean MIC of 4 mg/L was reached after 6, 68, and 44 min for plasma, SCT, and cancellous bone, respectively. For cortical bone, a mean MIC of 4 mg/L could not be reached.

Table 2.

Time (min) to mean concentrations of 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/L for plasma, subcutaneous adipose tissue, cancellous, and cortical bone (MICs)

| MIC 1 | MIC 2 | MIC 4 | MIC 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical bone | 18 | 110 | – | – |

| Cancellous bone | 17 | 27 | 44 | 105 |

| Subcutaneous adipose tissue | 20 | 36 | 68 | – |

| Plasma (unbound) | 1 | 3 | 6 | 11 |

Discussion

This is the first clinical study to investigate vancomycin bone concentrations using the MD technique. The main finding is that vancomycin bone and SCT penetration is incomplete and delayed. This contrasts with the traditional conception that antimicrobial plasma concentrations reflect tissue concentrations and calls for special considerations with respect to vancomycin surgical prophylaxis in the orthopedic setting. Although antimicrobial tissue targets for prevention of surgical site infections are unknown, attaining tissue concentrations that, at least, exceeds MICs of relevant pathogens throughout surgery seems prudent (Rybak et al. 2009, Whiteside 2016). The majority of orthopedic pathogens exhibit MIC values in the range of 0.5–2.0 mg/L for vancomycin, while pathogens with higher MICs are infrequently encountered (EUCAST 2017). Our data shows that in some combinations of individual and pathogen, adequate vancomycin tissue concentrations are reached with substantial delay or not at all, particularly in cortical bone. The obvious solution to overcome this problem would be a dose increase. However, due to the potential toxicity associated with higher doses, this approach may not be feasible. On the other hand, the rather long half-life of vancomycin is advantageous in order to maintain adequate concentrations for a prolonged period. Other ways of applying vancomycin may be considered, e.g. administering diluted vancomycin locally in the surgical wound or intra-articularly before closure of the capsule (Whiteside 2016). Despite the fact that vancomycin target tissue concentrations for prevention of orthopedic infections are unknown, our pharmacokinetic study suggest that 1,000 mg of vancomycin may not be a safe choice for single-drug antimicrobial prophylaxis for TKR in male patients with normal renal function

On a more basic pharmacokinetic level, it is noteworthy that both cortical bone AUC0–last and Cmax were lower than those of cancellous bone. These findings are in accordance with previous findings for cefuroxime and vancomycin in pig studies and suggest that bone may not be considered as a homogenous compartment (Tottrup et al. 2014, Bue et al. 2015, Tottrup et al. 2015). Not surprisingly, the tissue penetration ratios, we found in male TKR patients are lower than those found for juvenile (aged 5 months) pigs (Bue et al. 2015). From a pharmacokinetic perspective, it is also interesting that inter-tissue differences exist with respect to tissue penetration ratios. Consequently, it seems reasonable that surgical prophylaxis PK studies assess pharmacokinetics in all relevant tissues.

For practical reasons, vancomycin was administered postoperatively. As such, the present study setup does not truly mimic the clinical situation where antimicrobial prophylaxis is administered preoperatively. The MD measurements in bone were conducted in drill holes. Currently no gold standard approach exists to determine antimicrobial bone concentrations, but MD measurements in small drill holes seem to reflect true orthopedic perioperative conditions: MD measurements appear to be clinically relevant with respect to the orthopaedic prophylactic situation. Another advantage of MD is that it allows not only for continuous sampling, but also for sampling after the end of surgery, which provides more useful pharmacokinetic data compared with alternative approaches like bone biopsies.

Some important limitations must be addressed. First, the study population consisted of a group of healthy but overweight males (as depicted by their BMI) undergoing TKR. The results can only safely be regarded as representative for this specific population and maybe also only for this specific anatomical region. It would be interesting to assess the effect of weight-based dosing, sex, and alternative anatomical regions. Second, the local injection of adrenaline and ropivacaine at the end of surgery may also have affected the tissue pharmacokinetics to some extent since both adrenaline and ropivacaine induces vasoconstriction. This may indeed explain the low concentrations found in SCT. Nonetheless, it reflects the true perioperative situation for this specific population. Finally, a number of bone probes were malfunctioning, possibly indicating poor reproducibility for MD bone measurements. Nevertheless, the variance in bone and SCT measurements was comparable. Thus, the malfunctioning bone probes are more likely to reflect that application of MD for clinical bone measurements is technically demanding rather than questioning the validity of measurements that are obtained.

In summary, the postoperative penetration of vancomycin to bone and SCT was found to be delayed and incomplete in this population of male patients undergoing TKR surgery. These findings suggest that in some combinations of individual and pathogen, adequate vancomycin tissue concentrations may be reached with substantial delay or not at all. Consequently, vancomycin may not be a safe choice for single-drug antimicrobial prophylaxis for TKR in this population.

MB, MT, HBS, KS, OL, and PH initiated and designed the study. OL conducted the surgery and MB assisted with the placement of the probes. MB and PH collected the data. TLA performed the chemical analyses. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data was done by MT, HBS, KS, TMT, and TLA. All authors drafted and revised the manuscript.

Acta thanks Henrik Husted and Alex Soriano for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Barbour A, Schmidt S, Rout W R, Ben-David K, Burkhardt O, Derendorf H.. Soft tissue penetration of cefuroxime determined by clinical microdialysis in morbidly obese patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009; 34 (3): 231–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito N, Franco M, Ribera A, Soriano A, Rodriguez-Pardo D, Sorli L, et al. Time trends in the aetiology of prosthetic joint infections: A multicentre cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22 (8): 732 e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bue M, Birke-Sorensen H, Thillemann T M, Hardlei T F, Soballe K, Tottrup M.. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in porcine cancellous and cortical bone determined by microdialysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2015; 46 (4): 434–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST European Committee on Antimicrobail Susceptibility Testing. European Committee on Antimicrobail Susceptibility Testing. 2017; 2017; Data from the EUCAST MIC distribution website. https://mic.eucast.org/Eucast2/SearchController/search.jsp?action=init

- Hanberg P, Bue M, Birke Sorensen H, Soballe K, Tottrup M.. Pharmacokinetics of single-dose cefuroxime in porcine intervertebral disc and vertebral cancellous bone determined by microdialysis. Spine J 2016; 16 (3): 432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutschala D, Skhirtladze K, Kinstner C, Zeitlinger M, Wisser W, Jaeger W, et al. Effect of cardiopulmonary bypass on regional antibiotic penetration into lung tissue. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57 (7): 2996–3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukhadar C, Muller M.. Microdialysis: Current applications in clinical pharmacokinetic studies and its potential role in the future. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005; 44 (9): 895–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukhadar C, Frossard M, Mayer B X, Brunner M, Klein N, Siostrzonek P, et al. Impaired target site penetration of beta-lactams may account for therapeutic failure in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 2001; 29 (2): 385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzes-Cohen R, Farin D, Piva G, Ivry S, Sharony R, Amar R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin administered as prophylaxis before cardiac surgery. Ther Drug Monit 2000; 22 (6): 661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landersdorfer C B, Bulitta J B, Kinzig M, Holzgrabe U, Sorgel F.. Penetration of antibacterials into bone: Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and bioanalytical considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009; 48 (2): 89–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew D P, Waldvogel F A.. Osteomyelitis. Lancet 2004; 364 (9431): 369–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangram A J, Horan T C, Pearson M L, Silver L C, Jarvis W R. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee.. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999.. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999; 20 (4): 250–78; quiz 79-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton J W, Theuretzbacher U, Craig W A, Tulkens P M, Derendorf H, Cars O.. Tissue concentrations: Do we ever learn? J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61 (2): 235–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M. Science, medicine, and the future: Microdialysis. BMJ 2002; 324 (7337): 588–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo O, Grau I, Lora-Tamayo J, Gomez-Junyent J, Ribera A, Tubau F, et al. The changing epidemiology of bacteraemic osteoarticular infections in the early 21st century. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21 (3): 254 e1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pea F. Penetration of antibacterials into bone: What do we really need to know for optimal prophylaxis and treatment of bone and joint infections? Clin Pharmacokinet 2009; 48 (2): 125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak M J, Lomaestro B M, Rotschafer J C, Moellering R C, Craig W A, Billeter M, et al. Vancomycin therapeutic guidelines: A summary of consensus recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49 (3): 325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller D, Kolb J.. The internal reference technique in microdialysis: A practical approach to monitoring dialysis efficiency and to calculating tissue concentration from dialysate samples. J Neurosci Methods 1991; 40 (1): 31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schintler M V, Traunmuller F, Metzler J, Kreuzwirt G, Spendel S, Mauric O, et al. High fosfomycin concentrations in bone and peripheral soft tissue in diabetic patients presenting with bacterial foot infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 64 (3): 574–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla C, Patel V, Juluru R, Stagni G.. Quantification and prediction of skin pharmacokinetics of amoxicillin and cefuroxime. Biopharm Drug Dispos 2009; 30 (6): 281–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolle L B, Arpi M, Holmberg-Jorgensen P, Riegels-Nielsen P, Keller J.. Application of microdialysis to cancellous bone tissue for measurement of gentamicin levels. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004; 54 (1): 263–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottrup M, Hardlei T F, Bendtsen M, Bue M, Brock B, Fuursted K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefuroxime in porcine cortical and cancellous bone determined by microdialysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58 (6): 3200–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottrup M, Bibby B M, Hardlei T F, Bue M, Kerrn-Jespersen S, Fuursted K, et al. Continuous versus short-term infusion of cefuroxime: Assessment of concept based on plasma, subcutaneous tissue, and bone pharmacokinetics in an animal model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59 (1): 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trampuz A, Widmer A F.. Infections associated with orthopedic implants. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2006; 19 (4): 349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traunmuller F, Schintler M V, Metzler J, Spendel S, Mauric O, Popovic M, et al. Soft tissue and bone penetration abilities of daptomycin in diabetic patients with bacterial foot infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010a; 65 (6): 1252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traunmuller F, Schintler M V, Spendel S, Popovic M, Mauric O, Scharnagl E, et al. Linezolid concentrations in infected soft tissue and bone following repetitive doses in diabetic patients with bacterial foot infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010b; 36 (1): 84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorisalo S, Pokela R, Satta J, Syrjala H.. Internal mammary artery harvesting and antibiotic concentrations in sternal bone during coronary artery bypass. Int J Angiol 2000; 9 (2): 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside L A. Prophylactic peri-operative local antibiotic irrigation. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (1 Suppl A): 23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]