Abstract

Background

Critical illness requires specialist and timely management. The aim of this study was to create a geographic accessibility profile of the Scottish population to emergency departments and intensive care units.

Methods

This was a descriptive, geographical analysis of population access to ‘intermediate’ and ‘definitive’ critical care services in Scotland. Access was defined by the number of people able to reach services within 45 to 60 min, by road and by helicopter. Access was analysed by health board, rurality and as a country using freely available geographically referenced population data.

Results

Ninety-six percent of the population reside within a 45-min drive of the nearest intermediate critical care facility, and 94% of the population live within a 45-min ambulance drive time to the nearest intensive care unit. By helicopter, these figures were 95% and 91%, respectively. Some health boards had no access to definitive critical care services within 45 min via helicopter or road. Very remote small towns and very remote rural areas had poorer access than less remote and rural regions.

Keywords: Intensive care, GIS, access, Scotland

Introduction

Critical illness requires specialist care, which is typically not available in all hospitals. Delayed access to services has been shown to be associated with increased mortality and hospital length of stay.1–3 Ensuring equity of access is a key objective for healthcare systems,4 and quantifying the geographic accessibility of the population to critical care services plays an important role in this.

Previous evaluations of geographical accessibility have focused on specific conditions, or certain services. Wallace et al.5 conducted an evaluation of geographical access to severe acute respiratory failure centres in the United States, which revealed wide variation across states and regions. There have been evaluations of the accessibility to burn,6 trauma and neurosurgical centres in the United States and Canada,7–10 and trauma care in the United Kingdom.11,12 However, all of these studies considered isolated aspects of accessibility, rather than providing a comprehensive profile of access to critical care services.

The aim of this study was to conduct a population-based analysis of geographical access to critical care services in Scotland, with particular reference to the effects of rurality and inter-regional variations. Scotland has excellent geographically referenced population data, and a highly granular classification of rurality, facilitating such an evaluation.

Scotland has a mixed urban/rural population, with large cities as well as areas of low population density. The recently published National Clinical Strategy sets out a framework for the development of health services across Scotland for the next 15 years.13 It emphasises the importance of planning services at a population level and the development of hospital networks to deliver complex care. The accessibility of critical care services, across Scotland as a whole, has not previously been analysed in this context.

Methods

Study design

This is a geographical analysis of population and areal coverage. Geographical accessibility was defined as the percentage of the population that could reach a critical care service within a certain time (45 or 60 min), and the percentage of land area from which a hospital with a critical care service could be reached within this time.

Setting

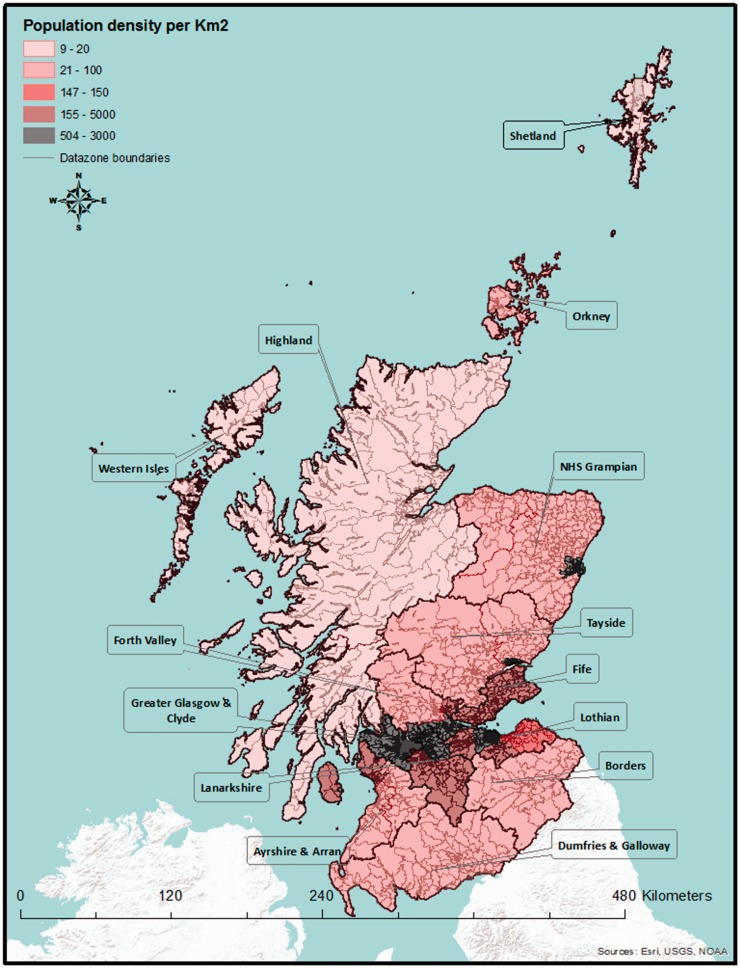

Scotland has a land area of 78,770 km2, constituting approximately one-third of the United Kingdom’s land mass, and a population of 5.4 million.14 Eighty-one percent of the Scottish population live in urban areas, predominantly in the so-called ‘Central Belt’, which extends from Glasgow in the West to Edinburgh in the East, and the coastal areas in the East and North East. Large areas, predominantly in the mountainous West and North West, are sparsely populated, with among the lowest population densities in Europe (Figure 1).14 Scotland has 790 islands, although only 95 are inhabited. The combined population of the Scottish islands is 103,000.15

Figure 1.

Population density in Scotland with datazones underlain.

Administrative regions and rurality

We analysed access for the population and country as a whole, as well as by administrative area (health board region), and rurality. There are 14 boards, of varying size, which are responsible for the delivery of healthcare services (Figure 1 and Table 1). Scotland has an established urban/rural classification scheme.16 The latest, eight-fold version of the classification divides the country into large urban areas, other urban areas, accessible small towns, remote small towns, very remote small towns, accessible rural areas, remote rural areas and very remote rural areas using a combination of settlement size and drive time (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 1.

Accessibility by road ambulance: Population and areal coverage, by health board.

| Health board |

Intermediate critical care facilities |

Definitive critical care facilities |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

|||||

| Name | km2 | n | km2 | % | n | % | km2 | % | n | % |

| Ayrshire and Arran | 3369 | 373,339 | 3369 | 100 | 373,339 | 100 | 2835 | 84 | 366,827 | 98 |

| Borders | 4732 | 113,615 | 4334 | 92 | 110,238 | 97 | 4334 | 92 | 110,238 | 97 |

| Dumfries and Galloway | 6426 | 151,302 | 6085 | 95 | 148,441 | 98 | 4672 | 73 | 121,149 | 80 |

| Fife | 1325 | 367,036 | 1325 | 100 | 367,036 | 100 | 1325 | 100 | 367,036 | 100 |

| Forth Valley | 2643 | 297,529 | 2296 | 87 | 296,616 | 100 | 2204 | 83 | 296,470 | 100 |

| Greater Glasgow and Clyde | 1104 | 1,143,934 | 1104 | 100 | 1,143,934 | 100 | 1104 | 100 | 1,143,934 | 100 |

| Grampian | 8736 | 568,800 | 6571 | 75 | 538,979 | 95 | 4938 | 57 | 480,225 | 84 |

| Highland | 32,593 | 320,067 | 13,046 | 40 | 246,329 | 77 | 5603 | 17 | 175,841 | 55 |

| Lanarkshire | 2242 | 651,635 | 2242 | 100 | 651,635 | 100 | 2242 | 100 | 651,635 | 100 |

| Lothian | 1724 | 834,461 | 1724 | 100 | 834,461 | 100 | 1724 | 100 | 834,461 | 100 |

| Orkney | 990 | 21,349 | 457 | 46 | 16,512 | 77 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shetland | 1467 | 23,154 | 598 | 41 | 14,919 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tayside | 7527 | 409,481 | 5669 | 75 | 407,069 | 99 | 5660 | 75 | 407,063 | 99 |

| Western Isles | 3060 | 28,396 | 1172 | 38 | 18,019 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Classification of critical care services

The Scottish Intensive Care Society audit group (SICSAG) lists 26 intensive care units (ICUs), in 23 hospitals.17 Most of these centres are University-affiliated hospitals or large district general hospitals located in areas of high population density. However, critical care is not only provided in ICUs - most emergency departments have the ability to intubate patients, and commence ventilatory and cardiovascular support, but other treatments, such as renal replacement therapy or intracranial pressure monitoring, are generally only available in ICUs. Critical care services were therefore defined as either ‘intermediate’ or ‘definitive’. Intermediate critical care was defined as the ability to provide advanced airway management, including drug-assisted intubation, cardiovascular monitoring with central and arterial lines and vasoactive drug treatment. This level of care would be expected in most emergency departments, even when hospitals do not have critical care ward facilities. Definitive critical care was defined as the level of care which would be expected from an ICU, including advanced respiratory and circulatory support, and renal replacement therapy, equating to level 3 critical care, as defined by the Intensive Care Society.18

Identification and geocoding of hospitals

We used reports from audit Scotland19 and SICSAG17 to identify centres which provide such services and to classify them. Thirty hospitals were identified, of which 20 have definitive critical care facilities. A further 10 offer intermediate services only. This study was focused on adult services, and we therefore excluded the two paediatric ICUs and a stand-alone specialist cardiothoracic ICU. The hospitals’ locations were georeferenced using Google maps.20 The WGS 1984 co-ordinate system was used throughout.

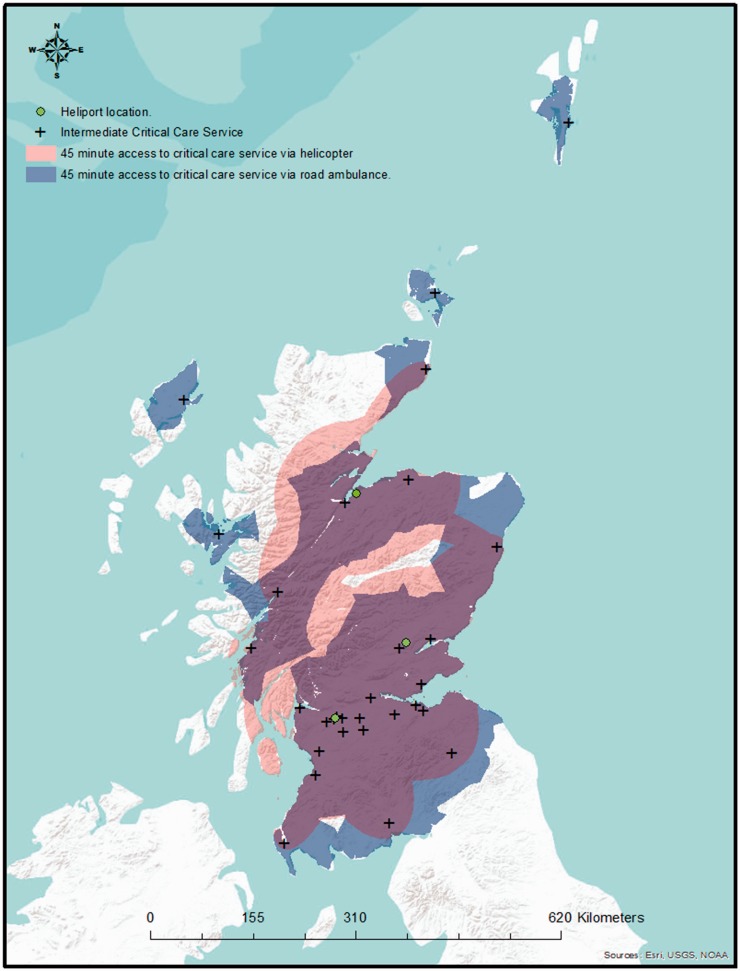

Helicopter locations

The Scottish Ambulance Service has three EC-145 helicopters, based in Glasgow, Perth and Inverness (Figure 2). The longitude and latitude of these locations were, again, determined using Google maps.20

Figure 2.

Location of critical care facilities, with 45-min drive times and 45-min helicopter access.

Access time threshold

The analyses are based on an ‘access time threshold’, defined as the time within which a patient can reach a desired level of care, from the point of being ready to depart from the patient’s location. This concept is widely used by trauma networks,7,10 but there is presently no equivalent guidance specifically relating to critically ill patients. The Scottish Trauma Network operates with a 45-min access time threshold,21 and we therefore used this figure for our primary analysis. However, other trauma systems use a 60-min threshold, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has recently advocated for a lengthening of the trauma network access time thresholds,22 based on experiences in England. We have, therefore, included a sensitivity analysis, using the 60-min threshold, as supplementary data.

Isochrone derivation

An area which can be reached from a central location within a set time, or from which a central location can be reached, is referred to as an isochrone.

Drive-time isochrones

For each hospital 45 and 60 min drive time isochrones were determined using ‘blue light’ travel times, defined as the speed limit plus 10 mph to simulate road ambulance travel. The drive-time isochrone calculations were performed by an external company (Mercator GeoSystems, Sheffield, UK), and used to create ‘shapefiles’, a file format widely used by geographical information systems (GIS).

Flight-time isochrones

We assumed that critically ill patients would initially be attended by a road ambulance, or local practitioner, before calling a helicopter. This model broadly reflects current practice. The total time to reach a hospital therefore comprised the helicopter’s flight time to the patient’s location, and the flight time from the patient’s location to hospital, as well as the start-up and loading times. The Scottish Ambulance Service’s helicopters are based at heliports, rather than hospitals, and the inbound and outbound flight times therefore differ, and the area from which a patient can be retrieved is defined by an ellipse, rather than a circle. The methodology used to calculate these ellipses is described in a previous publication.12 We calculated the size, location and orientation of these ellipses for each of the 90 combinations of heliport and hospital. We assumed a helicopter cruising speed of 250 km/h, and a total of 15 min of start-up and loading time (i.e. 30-min and 45-min flying time, respectively); 30-min and 45-min flight times equate to ellipses with major radii of 125 and 187.5 km. Minor radii vary depending on the bearing between hospital and heliport, and the major value of the major radius.

Population data

The Scottish Government uses a small area geography referred to as ‘datazones’ for the dissemination of census and statistical data. Datazones correlate with natural physical and societal boundaries, and have known populations, of between 500 and 1000 residents. These datazones and associated demographic data are freely available23 (Figure 1).

Spatial analysis

The spatial analysis was conducted using ArcGIS 10.1 (ESRI®, Redlands, California), a GIS package. The drive-time and helicopter isochrones were overlain onto the datazone shapefiles, containing the demographic and geographical data, including health board boundaries and urban/rural classification. The number of residents and the geographical area beneath the drive-time isochrones was calculated using the intersect feature. Where datazones were split by drive time or helicopter boundaries, a polygon-in-polygon analysis was used to determine an average population per km2 of that datazone. The new area was calculated, and from that, the population within the split polygon could be estimated. The sum of polygons was produced to give population and areas within a specified access time threshold to the nearest critical care service.

Results

Access to definitive critical care services

By road

Overall, 94% of the Scottish population live within a 45-min ambulance drive time of a definitive critical care service, but a 45-min drive time covers less than half of the Scottish landmass (47%).

Analysis by health board (Table 1) shows that regional population coverage varies from 0% to 100%. Fife, Forth Valley, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lanarkshire and Lothian health boards are able to provide complete population coverage. Ayrshire and Arran, Borders and Tayside health boards provide almost complete population coverage (98%, 97% and 99%, respectively), whereas coverage is lower in Dumfries and Galloway (80%), Grampian (84%) and Highland (55%). Areal coverage (Table 1) is complete in Fife, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lanarkshire and Lothian, but less in Ayrshire and Arran (84%), the Borders (92%), Dumfries and Galloway (73%), Forth Valley (83%), Grampian (53%) and Highland (17%). The population of the islands (Orkney, Shetland and Western Isles health boards) do not have access to definitive critical care services within the 45-min access time threshold.

Analysis by rurality (Table 2) reveals that population coverage is complete in large urban areas, and almost complete in other urban areas (99%), accessible small towns (98%) and accessible rural areas (95%). Population coverage is lower in remote small towns (73%) and remote rural areas (79%) and very low in very remote small towns (4%) and very remote rural areas (12%). Areal coverage (Table 2) closely follows the pattern of population coverage.

Table 2.

Accessibility by road ambulance: Population and areal coverage, by Scottish urban/rural classification category.

| Health board |

Intermediate critical care facilities |

Definitive critical care facilities |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

|||||

| Name | km2 | n | km2 | % | n | % | km2 | % | n | % |

| Large urban areas | 505 | 1,792,214 | 505 | 100 | 1,792,214 | 100 | 505 | 100 | 1,792,214 | 100 |

| Other urban areas | 691 | 1,780,740 | 690 | 100 | 1,778,865 | 100 | 673 | 97 | 1,759,115 | 99 |

| Accessible small towns | 188 | 451,419 | 188 | 100 | 451,419 | 100 | 186 | 99 | 444,448 | 98 |

| Remote small towns | 54 | 105,997 | 52 | 97 | 101,055 | 95 | 42 | 77 | 76,916 | 73 |

| Very remote small towns | 45 | 62,959 | 35 | 77 | 43,646 | 69 | 2 | 5 | 2789 | 4 |

| Accessible rural areas | 18,558 | 748,324 | 18,153 | 98 | 735,068 | 98 | 16,998 | 92 | 714,381 | 95 |

| Remote rural areas | 17,828 | 184,698 | 16,831 | 94 | 174,683 | 95 | 13,944 | 78 | 145,898 | 79 |

| Very remote rural areas | 40,066 | 176,503 | 13,467 | 34 | 90,632 | 51 | 4293 | 11 | 21,145 | 12 |

By helicopter

Ninety-one percent of the Scottish population can access definitive critical care services within the 45 min by helicopter. The Island health boards – Western Isles, Orkney and Shetland – have no population or areal coverage by helicopter. Seven health boards (Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lothian, Lanarkshire and Tayside) have complete population coverage. The Borders have 55% population coverage, Dumfries and Galloway 50%, Grampian 71% and Highland 67% (Table 1). Areal coverage is complete in Fife, Greater Glasgow and Clyde and Lanarkshire only, but near-complete in Lothian (99%) and Forth Valley (96%). Areal coverage is much lower in the remaining board areas and as low as 34% in the Highlands.

Table 2 shows the population coverage by helicopter, by degree of rurality. Large urban areas have complete population coverage by helicopter, and other urban areas have near-complete coverage (98%). Accessible small towns have 85%, and accessible rural areas 86% population coverage. Very remote small towns and very remote rural areas have the lowest population coverage (24% and 30%, respectively). Areal coverage again broadly follows population coverage.

Access to intermediate critical care services

By road

Ninety-six percent of the Scottish population reside within a 45-min ambulance drive time of the nearest intermediate critical care service. This equates to 64% of the Scottish landmass.

Analysis by health board (Table 3) shows that population coverage by road ranges from 63% to 100%. Six health boards (Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Forth Valley, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lanarkshire and Lothian) have complete population coverage. The health boards with lower population coverage are the Western Isles (63%), Shetland (64%), Orkney (77%) and Highland (77%). Areal coverage broadly follows population coverage, with lower coverage in the Highlands (40%), and on the Orkney (46%) and Shetland (41%) Islands and the Western Isles (38%).

Table 3.

Accessibility by helicopter: Population and areal coverage, by health board.

| Health board |

Intermediate critical care facilities |

Definitive critical care facilities |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

|||||

| Name | km2 | n | km2 | % | n | % | km2 | % | n | % |

| Ayrshire and Arran | 3369 | 373,339 | 3369 | 100 | 373,339 | 100 | 3124 | 93 | 372,207 | 100 |

| Borders | 4732 | 113,615 | 2706 | 57 | 62,134 | 55 | 2706 | 57 | 62,134 | 55 |

| Dumfries and Galloway | 6426 | 151,302 | 3411 | 53 | 89,847 | 59 | 2921 | 45 | 76,170 | 50 |

| Fife | 1325 | 367,036 | 1325 | 100 | 367,036 | 100 | 1325 | 100 | 367,036 | 100 |

| Forth Valley | 2643 | 297,529 | 2643 | 100 | 297,529 | 100 | 2544 | 96 | 297,212 | 100 |

| Greater Glasgow and Clyde | 1104 | 1,143,934 | 1104 | 100 | 1,143,934 | 100 | 1104 | 100 | 1,143,934 | 100 |

| Grampian | 8736 | 568,800 | 6247 | 72 | 544,544 | 96 | 5058 | 58 | 406,419 | 71 |

| Highland | 32,593 | 320,067 | 17,621 | 54 | 273,090 | 85 | 11,075 | 34 | 215,894 | 67 |

| Lanarkshire | 2242 | 651,635 | 2242 | 100 | 651,635 | 100 | 2242 | 100 | 651,635 | 100 |

| Lothian | 1724 | 834,461 | 1714 | 99 | 834,299 | 100 | 1714 | 99 | 834,299 | 100 |

| Orkney | 990 | 21,349 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shetland | 1467 | 23,154 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tayside | 7527 | 409,481 | 7461 | 99 | 409,388 | 100 | 6796 | 90 | 408,807 | 100 |

| Western Isles | 3060 | 28,396 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The analysis by urban/rural classification category (Table 4) shows that 100% of the population residing in large urban areas, other urban areas and accessible small towns have access to intermediate critical care services by road within 45 min. Population coverage is also high in remote small towns (95%), accessible rural areas (98%) and remote rural areas (95%), but lower in very remote small towns (69%) and very remote rural areas (51%). Again, areal coverage broadly follows population coverage.

Table 4.

Accessibility by helicopter: Population and areal coverage, by Scottish urban/rural classification category.

| Scottish rural urban category |

Intermediate critical care facilities |

Definitive critical care facilities |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

Area |

Population |

|||||

| Name | km2 | n | km2 | % | n | % | km2 | % | n | % |

| Large urban areas | 505 | 1,792,214 | 505 | 100 | 1,792,214 | 100 | 505 | 100 | 1,792,214 | 100 |

| Other urban areas | 691 | 1,780,740 | 689 | 100 | 1,745,686 | 98 | 689 | 100 | 1,745,686 | 98 |

| Accessible small towns | 188 | 451,419 | 182 | 97 | 436,087 | 97 | 177 | 94 | 381,533 | 85 |

| Remote small towns | 54 | 105,997 | 42 | 77 | 75,622 | 71 | 33 | 61 | 53,505 | 50 |

| Very remote small towns | 45 | 62,959 | 22 | 49 | 31,743 | 50 | 9 | 20 | 14,856 | 24 |

| Accessible rural areas | 18,558 | 748,324 | 15,677 | 84 | 671,349 | 90 | 14,498 | 78 | 645,322 | 86 |

| Remote rural areas | 17,828 | 184,698 | 14,342 | 80 | 150,435 | 81 | 12,493 | 70 | 136,513 | 74 |

| Very remote rural areas | 40,066 | 176,503 | 18,361 | 46 | 71,664 | 41 | 12,190 | 30 | 53,052 | 30 |

By helicopter

Ninety-five percent of the Scottish population can be retrieved and taken to the nearest intermediate critical care service within 45 min by helicopter, but there is considerable variation between health boards (Table 3). The Island health boards lie outwith of the range of the 45-min helicopter access time threshold, and thus have no population or areal coverage. The health boards serving the central belt all have complete population coverage. Highland (85%), Grampian (96%), the Borders (55%) and Dumfries and Galloway (59%) have lower degrees of population coverage. Areal coverage broadly follows this pattern, albeit with lower coverage in the Highlands (54%).

Analysis by urban/rural classification (Table 4) shows that large and other urban areas and accessible small towns have complete or near-complete population and areal coverage. Very remote small towns and very remote rural areas have the lowest population (50% and 41%, respectively) and areal (49% and 46%) coverage, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis: 60-min access time threshold

The results of the sensitivity analysis using a 60-min (rather than 45 min) access time threshold are shown in Supplementary Tables 6–9. As expected, lengthening the access time threshold increases coverage. In terms of access to definitive critical care facilities, population coverage by road is complete or near-complete in all areas except the Highlands (61%), increased to 80% using helicopters. The Islands continue to have no coverage. All categories of the urban/rural classification have complete or near-complete access to definitive critical care facilities, by road and helicopter, except very remote small towns and very remote rural areas, which have 19% and 21% population coverage by road, respectively. Population coverage in these areas is increased to 47% using helicopters.

In terms of access to intermediate critical care facilities, a 60-min access time threshold marginally improves health board population coverage by road. By helicopter, however, parts of the Orkney Islands become accessible. Lengthening the access time threshold improves population road coverage in very remote small towns and rural areas. In addition, helicopter use increases coverage in these areas to 90% and 73%, respectively.

Discussion

We have conducted a population-based evaluation of geographical access to critical care services in Scotland. We have established a methodology using freely accessible data to describe the proportion of the population that can access critical care services within 45 to 60 min, by road and by air.

There is an increasing interest in the concept of equity of access to healthcare resources.4,24 In countries with diverse geography, such as Scotland, ensuring equity is challenging, with evidence that there may be disparities in equity of access to critical care service. In another study from Scotland, Docherty et al. have shown that, after standardization for gender and socioeconomic status, there was evidence of regional variation in ICU admission rates for elderly patients. The authors concluded that their data indicated possible rationing, based on age, and geographic variation in access to care.25 Quantifying the geographical access to critical care provides information on where these inequities lie, and how such disparities might be reduced.

We have shown that, residing within a 45-min drive to the nearest definitive critical care facility, and the aeromedical retrieval network providing definitive critical care access for 91% of the population, also within 45 min. An even greater proportion of the population have access to intermediate critical care facilities within this timeframe. In some areas, a greater proportion of the population can access critical care services within 45 min via road ambulance rather than air ambulance. This finding is the result of the location of the heliports, in Perth, Glasgow and Inverness. We have previously analysed these locations in relation to major trauma.12

Our data suggest that the current critical care network infrastructure can serve the majority of the population who develop a critical illness in a time-sensitive fashion. As might be expected, remote areas, and health boards serving these areas, have poorer access to critical care services, with certain isolated communities having poor access to level three critical care facilities, even via helicopter. We have shown that, of the mainland health boards, Grampian and Highland have relatively poor population access to critical care. Similarly, in terms of rurality, very remote small towns and very remote rural areas have poor access to definitive critical care facilities, but reasonable access to intermediate care. Remote small towns, accessible rural areas and remote rural areas have surprisingly good access, even to definitive critical care. The number of people who live in remote areas is relatively small, but in a healthcare system which aims to provide equity of access, consideration should be given to addressing these inequities. This would, most likely, involve the enhancement of local facilities, as well as the existing aeromedical retrieval and transfer service, but requires further study.26

This analysis has limitations. It is based exclusively on population distribution data, and the geographical distribution of patients who suffer critical illness may differ from that of the general population. The most frequent cause of critical illness outside of the home is trauma, but the organisation of trauma services differs from that of critical care, and has been extensively analysed.11,12 The use of an inbound-leg access time threshold can be questioned – arguably, the total time from notification of the ambulance service (regardless of whether by the patient, relatives, or a clinician) to arrival in hospital may be more important. However, most analyses have focused on inbound time only, at least in part because it is difficult to accurately model the outward leg of a journey – ambulances do not return to a ‘base location’ before attending the next call. In contrast, our model of helicopter tasking does incorporate both outbound and inbound legs, which reflects current practice, because most critically ill patients are seen by a local provider first. However, there are a number of factors, which we were not able to include in this model, including adverse weather conditions, night time flying and the time taken to transfer the patient from landing to the emergency department at the destination hospital. At present, the Scottish Ambulance Service does not have night-flying capability, which means that the realised access is less than half of the theoretical access.

However, this study also has several strengths. The most important are the population-based design, which provides a comprehensive picture of geographical accessibility, and the use of elliptical isochrones to monitor helicopter coverage. The use of smaller geographical units, such as health board regions, and the urban/rural classification, adds detail and granularity, and permits the identification of settings with poorer access. Furthermore, the analyses described here are technically straightforward, and can be conducted using freely and readily available data, making the techniques easily reproducible.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of profiling the accessibility of services using geographically referenced population distribution data. Overall, there is good population access to critical care services in Scotland, but there remain disparities, in identifiable areas. The impact of these disparities on utilisation rates and clinical outcomes requires further study.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Health Services Research Unit at the University of Aberdeen receives funding from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone.

References

- 1.Hung S-C, Kung C-T, Hung C-W, et al. Determining delayed admission to intensive care unit for mechanically ventilated patients in the emergency department. Crit Care 2014; 18: 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso LTQ, Grion CMC, Matsuo T, et al. Impact of delayed admission to intensive care units on mortality of critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care 2011; 15: R28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 1477–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver A, Mossialos E. Equity of access to health care: outlining the foundations for action. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004; 58: 655–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Seymour CW, et al. Geographic access to high capability severe acute respiratory failure centers in the United States. PLoS One 2014; 9: e94057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klein MB, Kramer CB, Nelson J, et al. Geographic access to burn center hospitals. JAMA 2009; 302: 1774–1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branas CC, MacKenzie EJ, Williams JC, et al. Access to trauma centers in the United States. JAMA 2005; 293: 2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nance ML, Carr BG, Branas CC. Access to pediatric trauma care in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163: 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hameed SM, Schuurman N, Razek T, et al. Access to trauma systems in Canada. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care 2010; 69: 1350–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward MJ, Shutter LA, Branas CC, et al. Geographic access to US neurocritical care units registered with the Neurocritical Care Society. Neurocrit Care 2012; 16: 232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jansen JO, Morrison JJ, Wang H, et al. Access to specialist care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015; 79: 756–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodds N, Emerson P, Phillips S, et al. Analysis of aeromedical retrieval coverage using elliptical isochrones. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016; 82: 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scottish Government. A national clinical strategy for Scotland, www.gov.scot/Resource/0049/00494144.pdf (2016, accessed 10 May 2016).

- 14.National Records of Scotland Indexing Team. National records of Scotland, www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data (accessed 10 May 2016).

- 15.National Records of Scotland. 2011 Census: first results on population and household estimates for Scotland—Release 1C (Part Two). Edinburgh: National Records of Scotland, 2013.

- 16.Scottish Government R and ES and ASD. Scottish government urban/rural classification 2013–2014, www.gov.scot/Resource/0046/00464780.pdf (2014, accessed 18 October 2016).

- 17.Scottish Intensive Care Society audit group, www.sicsag.scot.nhs.uk/ (accessed 25 May 2017).

- 18.The Intensive Care Society: levels of critical care for adult patients: standards and guidelines, www.ics.ac.uk/professional/standards_safety_quality/standards_and_guidelines/levels_of_critical_care_for_adult_patients (2015, accessed 1 June 2017).

- 19.Audit Scotland. Accident and emergency: briefing paper to the Public Audit Committee. Edinburgh: Audit Scotland, 2015.

- 20.Google maps, www.googlemaps.com (2017, accessed 5 April 2017).

- 21.Calderwood C. Saving lives. Giving life back, www.traumacare.scot/files/National-Trauma-Network-Implementation-Group-Jan-2017.pdf (2017, accessed 14 April 2017).

- 22.NICE. Major trauma: service delivery|guidance and guidelines, www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng40 (2016, accessed 14 April 2017).

- 23.The Scottish Government. Scottish neighbourhood statistics guide, www.gov.scot/Publications/2005/02/20697/52626 (2005, accessed 10 May 2016).

- 24.Government at a Glance 2011 Equity in access to health care XII. Government performance indicators from selected sectors, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2011-en (2011, accessed 19 September 2016).

- 25.Docherty AB, Anderson NH, Walsh TS, et al. Equity of access to critical care among elderly patients in Scotland: a national cohort study. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Scottish Government. Towards a single national specialist transport service for Scotland – ScotSTAR strategic vision national planning forum – Specialist transport services strategic review. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government, 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.