Abstract

Objective

To examine how smokers perceive FDA oversight of e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars.

Methods

Current US smokers (N = 1,520) participating in a randomized clinical trial of pictorial cigarette pack warnings completed a survey that included questions about attitudes toward new FDA regulations covering newly deemed tobacco products (ie, regulation of e-cigarettes, nicotine gels or liquids used in e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars).

Results

Between 47% and 56% of current smokers viewed these new FDA regulations favorably and between 17% – 24% opposed them. Favorable attitudes toward the regulations were more common among smokers with higher quit intentions (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.17, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.33) and more negative beliefs about smokers (aOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.33). Participants with higher education, higher income, and previous exposure to e-cigarette advertisements had higher odds of expressing positive attitudes toward the new FDA regulations (p < .05).

Conclusions

Almost half of current smokers viewed FDA regulation of newly deemed tobacco products favorably. Local and state policy-makers and tobacco control advocates can build on this support to enact and strengthen tobacco control provisions for e-cigarettes, cigars, and hookah.

Keywords: public policy, public opinion, non-cigarette tobacco products

INTRODUCTION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. In 2016, the agency released a new deeming rule extending its regulatory authority to include e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars.1 Other regulations already covered many of these newly deemed products to some extent because state and local governments can enact stronger tobacco prevention ordinances than called for in federal regulations.2 For instance, some nonfederal regulations restrict access to these products to youth under the age of 18, ban use of these products where cigarette smoking is prohibited, or raise taxes.3,4 The recent FDA deeming rule requires that all products derived from tobacco, including e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars, meet a public health standard set forth in the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, include health warnings on product packages and advertisements, and not be sold to youth under the age of 18.1 Additionally, manufacturers of these newly deemed tobacco products must now report harmful and potentially harmful constituents, not make modified risk claims on tobacco products (unless authorized by the FDA), and obtain authorization before selling new products.1

Enforcement of some of these new regulations began in August, 2016,1 but prior to this time several groups filed lawsuits against the FDA.5 Many of these lawsuits challenged the classification of e-cigarettes as “tobacco products”; others contested the regulation prohibiting the use of the term “mild” in tobacco products.5 These lawsuits may delay enforcement of some of these new regulations.

With impending enforcement, examining how the public perceives regulations of newly deemed tobacco products is timely. Attitudes toward tobacco control policies are associated with implementation, enforcement, and effectiveness.6,7 For instance, a review by the Interactional Agency for Research on Cancer concluded that “public attitudes are likely to impact how well such laws are complied with and enforced; hence, how well these laws achieve health protection goals.”8, p. 93 Specifically, when laws are enacted without public support, poor compliance can occur (especially for voluntary control measures, such as smoke-free homes).8 Compliance has been higher in countries that conducted public education campaigns accompanying the law and where there was increased public support.8 Additionally, a cross-sectional study of California youth found associations between favorable attitudes toward anti-tobacco policies and advocacy behaviors, such as asking someone not to smoke.9

Moreover, studies assessing policy attitudes can illuminate potential messages for media campaigns designed to increase public support for and compliance with regulation.10,11 Before implementation of a new law, media campaigns can inform individuals of the upcoming law and its rationale; after implementation, media campaigns can also increase support and compliance, typically by emphasizing the law’s benefits and thanking individuals for helping with successful implementation.12 Research suggests that high compliance exists in jurisdictions where media campaigns have been aired.13–15 For instance, a study of a social marketing campaign designed to promote Mexico City’s 2008 smoke-free law found an increase in support of the law and in increase in its perceived benefits.12 The FDA also uses media campaigns to encourage voluntary compliance of retailers with Tobacco Control Act regulations.16

Finally, state and local tobacco control policy-makers can use information garnered from studies examining policy attitudes to engage in local actions, including counter-marketing strategies, enforcement of provisions, and adoption of strengthened local tobacco control provisions. For instance, interviews with 444 state legislators found that perceived constituent support was associated with legislators’ intention to vote for a tax increase.6 Thus, research on policy attitudes can inform local and state policy-makers as they enact stronger tobacco control provisions. New York City, for example, relied on several strategies to build a spectrum of public support when seeking to raise the minimum age to purchase tobacco.17 Several other examples exist of state and local organizations using data about policy attitudes to enact stronger tobacco control efforts.18–20

Examining attitudes of smokers is especially important. When individuals perceive policies to be too restrictive, they may respond by ignoring such policies or opposing them.21,22 Smokers, who likely place greater importance on tobacco than non-smokers, may therefore react more negatively to potential tobacco control policies.21 Indeed, previous research has found that smokers are less supportive of tobacco control policies than non-smokers,10,23,24 and while data are limited, smokers may react more negatively to tobacco control efforts, such as cigarette pack warnings.21

Previous research has examined attitudes toward e-cigarette regulation, finding a moderate to high proportion of favorable attitudes for different e-cigarette regulations, depending on the type of regulation, participant characteristics, and setting (eg, geographic location).25,26 For instance, youth access restrictions are viewed more favorably than other types of regulations and smokers seem to have less favorable attitudes to regulations than non-smokers.25,26 However, no studies to our knowledge have examined attitudes for regulation of cigars or hookah, and none has done so exclusively with smokers. Our study examined attitudes toward FDA regulation of newly deemed tobacco products (ie, e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars) among a large sample of current US smokers.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Data for our study came from a randomized clinical trial of pictorial warnings on cigarette packs. Recruitment occurred from September 2014 to August 2015 in North Carolina and California. Participants were age 18 or older and current smokers (ie, had smoked more than 100 lifetime cigarettes and smoked every day or some days). The trial randomized 2,149 smokers to receive text-only warnings or pictorial warnings on their cigarette packs for 4 weeks. Participants completed surveys at the baseline visit and then at each weekly visit. Of the 1,731 participants who attended the third study visit when policy attitudes were assessed, we dropped data for 211 participants (12%) who had missing data on any of the variables examined, creating an analytic sample of 1,520 smokers. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved study procedures, and participants provided their written informed consent. More details about the study methods are available elsewhere.27

Measures

Policy attitudes

Four survey items assessed attitudes toward FDA regulation of newly deemed tobacco products. During the third week of the study, the survey included 4 items that read, “Do you think the FDA should regulate,” 1) “e-cigarettes and other vaping devices,” 2) “nicotine gels or liquids used in e-cigarettes and other vaping devices,” 3) “cigars,” and 4) “tobacco used for water pipes and hookah.” Response options to each of the items were “yes” (coded as 1), “no” (coded as 0), and “don’t know” (coded as 0). To create an index of attitudes toward FDA regulations of newly deemed tobacco products, we summed the 4 policy support variables (range 0–4, with higher scores indicating more favorable attitudes). Because the resulting index was strongly bimodal, we dichotomized scores for individuals who had favorable attitudes toward most regulations (ie, thought FDA should regulate 3 or all of the 4 products) vs. individuals who did not have favorable attitudes toward most regulations (ie, thought FDA should regulate 0, 1, or 2 products).

Demographics

Demographic characteristics assessed were race (white, Black / African American, or other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), gender (male, female, or transgender), sexual orientation (straight/heterosexual or gay, lesbian, or bisexual), age, poverty status (classified as above or below 150% of the Federal Poverty Line), and education. The dataset also included site (North Carolina or California) and trial arm (whether participants were assigned to receive pictorial warnings or text-only warnings).

Tobacco-related correlates

Tobacco-related correlates included smoking frequency, quit intentions, tobacco prevention media campaign awareness, e-cigarette advertising exposure, positive/negative smoker prototypes, positive/negative e-cigarette user prototypes, trait reactance, e-cigarette use, cigar use, and hookah use.

The smoking frequency survey item read, “On how many of the last 7 days did you smoke cigarettes?”. We classified participants as daily smokers if they reported smoking on all 7 days and non-daily smokers if they reported smoking on 1–6 days.28 The quit intention item read, “Are you planning to quit smoking…” with response options for “within the next month”, “within the next 6 months”, “sometime in the future beyond 6 months” or “not planning to quit”.29 We reverse coded responses so that item scores ranged from 1–4, with 4 indicating higher intentions.

Because media campaign awareness may be associated with policy attitudes,30 we assessed tobacco prevention media campaign exposure by asking whether participants had seen 4 Real Cost campaign advertisements or 1 Tips from Former Smokers campaign advertisement in the past 4 weeks. We dichotomized exposure as “yes” (if participants recalled seeing at least 1 advertisement, coded as 1) or “no” (if participants did not recall seeing any advertisements, coded as 0). Likewise, since previous research has found associations between exposure to information and advertising about e-cigarettes and public support for e-cigarette regulations,26,31 we assessed e-cigarette advertising exposure. The survey asked, “In the last 30 days, have you seen or heard any advertisements for e-cigarettes?” and dichotomized exposure as “yes” (coded as 1) or “no” (coded as 0). We adapted this item from the Wave 2 survey of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study.32

Previous research has found smoker prototypes to be associated with willingness/interest in trying tobacco products and relapse after quitting.33–35 However, no studies to our knowledge, have looked at it as a correlate of policy attitudes. The survey assessed positive (4 items) and negative smoker prototypes (4 items) by asking participants to consider “…how much the following characteristics describe a typical cigarette smoker your age.”33,36 The 5-point scale ranged from “not at all” (coded as 1) to “very much” (coded as 5). We created a mean score for positive smoker prototypes (cool, smart, sexy, healthy; α = .79) and for negative smoker prototypes (disgusting, unattractive, immature, inconsiderate; α = .82). The survey used the same items to assess positive (α = .86) and negative (α = .86) e-cigarette user prototypes, replacing “cigarette smoker” with “e-cigarette user.”

To assess e-cigarette, cigar, and hookah use, the survey assessed ever use (even one or 2 times) and use during the previous week. Cigar use included premium cigars, little cigars, and cigarillos. We classified participants as “never used”, “ever used”, or “used in past week”.

Since some research suggests that reactance is associated with lower support for tobacco control policies,21 we included a measure of trait reactance as a correlate of attitudes toward FDA regulations. The survey used 11 items from the Hong Psychological Reactance Scale that measures trait psychological reactance in response to different scenarios (eg, “I become angry when my freedom of choice is restricted”).37 The response scale ranged from strongly disagree (coded as 1) to strongly agree (coded as 5); we created a scale by averaging the responses (α = .86).38

Data Analysis

We first examined correlates of positive attitudes toward FDA regulations of newly deemed tobacco products using bivariate logistic regressions. We then conducted a multivariable logistic regression, including correlates from the bivariate analyses that were statistically significant with p < .10. Results included odds ratios (ORs), adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and confidence intervals (CI). Analyses used SAS version 9.4 survey procedures (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We set critical α = .05 and used 2-tailed statistical tests.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Most participants were ages 25 to 54 (68.2%) (Table 1). The sample was diverse, with a substantial number of African American (44.9%), low income (52.8%), low education (28.4% reported a high school degree or less), and sexual minority (17.1% identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual) participants. More than three-quarters of the sample were daily smokers (81.1%), and many participants were ever users of hookah (30.5%), cigars (39.3%), or e-cigarettes (47.4%).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, N = 1,520

| Characteristic | N (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Trial arm | |

| Text-only warnings | 768 (50.5) |

| Pictorial warnings | 752 (49.5) |

| Study site | |

| California | 822 (54.1) |

| North Carolina | 698 (45.9) |

| Age, years | |

| 18–24 | 215 (14.1) |

| 25–39 | 573 (37.7) |

| 40–54 | 464 (30.5) |

| ≥55 | 268 (17.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 721 (47.4) |

| Female | 773 (50.9) |

| Transgender | 26 (1.7) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight or heterosexual | 1260 (82.9) |

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | 260 (17.1) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |

| No | 1413 (93.0) |

| Yes | 107 (7.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 578 (38.0) |

| Black or African American | 683 (44.9) |

| Other | 259 (17.0) |

| Education | |

| High school degree or less | 432 (28.4) |

| Some college | 747 (49.1) |

| College graduate | 248 (16.3) |

| Graduate degree | 93 (6.1) |

| Low income <150% of federal poverty level | |

| No | 717 (47.2) |

| Yes | 803 (52.8) |

| Smoking frequency | |

| Daily | 1232 (81.1) |

| Non-daily | 288 (19.0) |

| Quit intentions, mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.8) |

| Tobacco prevention media campaign exposure | |

| Not exposed | 488 (32.1) |

| Exposed | 1032 (67.9) |

| E-cigarette advertising exposure in the past 30 days | |

| Not exposed | 580 (38.2) |

| Exposed | 940 (61.8) |

| Positive e-cigarette user prototype, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Negative e-cigarette user prototype, mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.9) |

| Positive smoker prototype, mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.9) |

| Negative smoker prototype, mean (SD) | 2.0 (0.9) |

| E-cigarette use | |

| Never used | 579 (38.1) |

| Ever used | 721 (47.4) |

| Used in past week | 220 (14.5) |

| Cigar use | |

| Never used | 608 (40.0) |

| Ever used | 597 (39.3) |

| Used in past week | 315 (20.7) |

| Hookah use | |

| Never used | 971 (63.9) |

| Ever used | 464 (30.5) |

| Used in past week | 85 (5.6) |

| Trait reactance, mean (SD) | 2.9 (0.7) |

Attitudes toward FDA regulations of newly deemed tobacco products

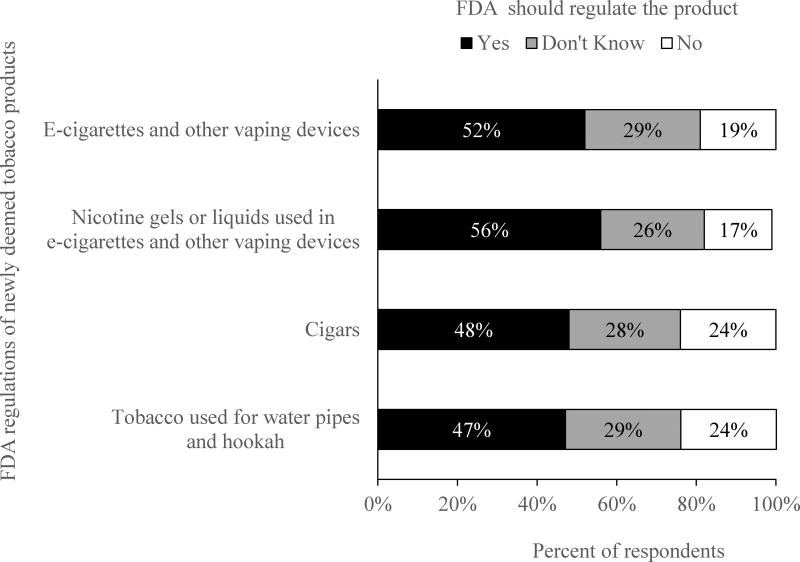

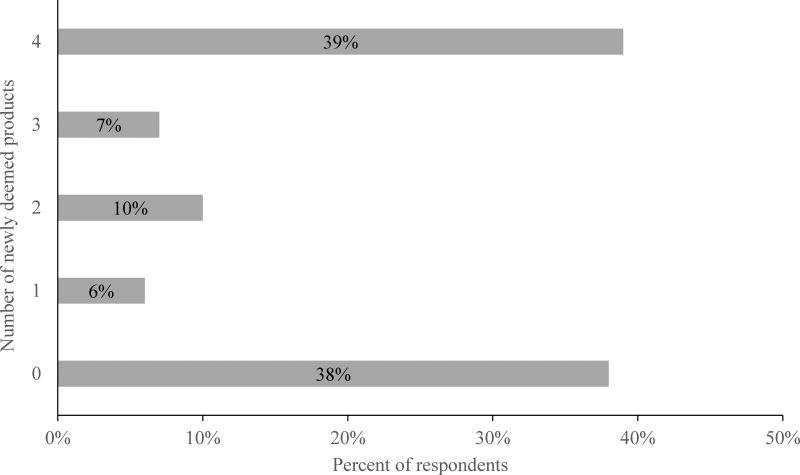

About half of respondents reported that FDA should regulate each newly deemed tobacco product (Figure 1). Smokers favored regulation of e-cigarette liquids and nicotine gels (56.2%) most, followed by regulation of e-cigarettes (51.8%), cigars (47.8%), and hookah (47.0%). Nearly one-third of smokers (26% to 29%) reported that they did not know whether they supported the regulations, and smaller percentages of smokers (17% to 24%) opposed these regulations. Slightly less than half (45.8%) of the participants had favorable attitudes toward 3 or 4 of the 4 regulations assessed (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Attitude Toward FDA Regulation of Newly Deemed Tobacco Products

Figure 2.

Number of Newly Deemed Tobacco Products that FDA Should Regulate

Correlates of favorable attitudes toward FDA regulation

Stronger quit intentions (aOR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.33) and more negative beliefs about smokers (aOR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.33) were associated with having favorable attitudes towards new FDA regulations in multivariable analysis (Table 2). Additionally, smokers who reported exposure to e-cigarette advertisements had higher odds of favorable attitudes than smokers who did not report exposure (aOR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.78). Smokers categorized as low income had lower odds of favorable attitudes than their higher-income counterparts (aOR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.58, 0.91). Smokers who reported some college (aOR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.93), a college degree (aOR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.45, 2.96), or a graduate degree (aOR: 2.94, 95% CI: 1.75, 4.93) had higher odds of favorable attitudes than smokers with a high school degree or less. In bivariate analyses, but not in multivariable analyses, having favorable attitudes toward new FDA regulations was less common among black respondents; respondents with positive smoker prototypes; respondents with positive e-cigarette user prototypes; and respondents who used cigars in the past week, whereas favorable attitudes were more common among respondents who had ever used e-cigarettes or ever used hookah.

Table 2.

Correlates of Favorable Attitudes Toward FDA Regulation of Newly Deemed Tobacco Products, N = 1,520

| Characteristic | Number supporting FDA regulations/total number in each category (%) |

Unadjusted models OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted model aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial arm | |||

| Text-only warnings | 352/768 (45.8) | REF | |

| Pictorial warnings | 344/752 (45.7) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.22) | |

| Study site | |||

| California | 391/822 (47.6) | REF | |

| North Carolina | 305/698 (43.7) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.05) | |

| Age, years | |||

| 18–24 | 98/215 (45.6) | REF | |

| 25–39 | 263/573 (45.9) | 1.01 (0.74, 1.39) | |

| 40–54 | 213/464 (45.9) | 1.01 (0.73, 1.40) | |

| ≥55 | 122/268 (45.5) | 1.00 (0.70, 1.43) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 328/721 (45.5) | REF | |

| Female | 355/773 (45.9) | 1.02 (0.83, 1.25) | |

| Transgender | 13/26 (50.0) | 1.20 (0.55, 2.62) | |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Straight or heterosexual | 564/1260 (44.8) | REF | REF |

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | 132/260 (50.8) | 1.27 (0.97, 1.66) | 1.17 (0.88, 1.55) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |||

| No | 646/1413 (45.7) | REF | |

| Yes | 50/107 (46.7) | 1.04 (0.70, 1.54) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 299/578 (51.7) | REF | REF |

| Black or African American | 266/683 (39.0) | 0.60 (0.48, 0.75)* | 0.89 (0.68, 1.16) |

| Other | 131/259 (50.6) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.28) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.58) |

| Education | |||

| High school degree or less | 142/432 (32.9) | REF | REF |

| Some college | 347/747 (46.5) | 1.77 (1.38, 2.27)* | 1.48 (1.14, 1.93)* |

| College graduate | 144/248 (58.1) | 2.83 (2.05, 3.90)* | 2.07 (1.45, 2.96)* |

| Graduate degree | 63/93 (67.7) | 4.29 (2.66, 6.92)* | 2.94 (1.75, 4.93)* |

| Low income, <150% of federal poverty level | |||

| No | 386/717 (53.8) | REF | REF |

| Yes | 310/803 (38.6) | 0.54 (0.44, 0.66)* | 0.73 (0.58, 0.91)* |

| Smoking frequency | |||

| Daily | 122/288 (42.4) | REF | |

| Non-daily | 574/1232 (46.6) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.54) | |

| Quit intentions | 1.26 (1.12, 1.43)* | 1.17 (1.02, 1.33)* | |

| Tobacco prevention media campaign exposure | |||

| Not exposed | 239/488 (49.0) | REF | REF |

| Exposed | 457/1032 (44.3) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.03) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.17) |

| E-cigarette advertising exposure in the past 30 days | |||

| Not exposed | 233/580 (40.2) | REF | REF |

| Exposed | 463/940 (49.3) | 1.45 (1.17, 1.78)* | 1.43 (1.14, 1.78)* |

| Positive e-cigarette user prototype | 0.83 (0.74, 0.92)* | 0.89 (0.78, 1.01) | |

| Negative e-cigarette user prototype | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | ||

| Positive smoker prototype | 0.87 (0.77, 0.97)* | 0.94 (0.82, 1.09) | |

| Negative smoker prototype | 1.14 (1.02, 1.27)* | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33)* | |

| E-cigarette use | |||

| Never used | 244/579 (41.1) | REF | REF |

| Ever used | 350/721 (48.5) | 1.30 (1.04, 1.62)* | 1.08 (0.84, 1.39) |

| Used in past week | 102/220 (46.4) | 1.19 (0.87, 1.62) | 1.13 (0.77, 1.60) |

| Cigar use | |||

| Never used | 282/608 (46.4) | REF | REF |

| Ever used | 294/597 (49.3) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.41) | 0.96 (0.74, 1.24) |

| Used in past week | 120/315 (38.1) | 0.71 (0.54, 0.94)* | 0.83 (0.61, 1.13) |

| Hookah use | |||

| Never used | 425/971 (43.8) | REF | REF |

| Ever used | 239/464 (51.5) | 1.37 (1.09, 1.70)* | 1.08 (0.82, 1.42) |

| Used in past week | 32/85 (37.7) | 0.78 (0.49, 1.23) | 0.91 (0.54, 1.53) |

| Trait reactance | 0.89 (0.77, 1.03) |

Note. The multivariable regression model included variables with p values <.10 in bivariate analyses.

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; REF= reference category.

p ≤ .05

DISCUSSION

Almost half of adult smokers in our study had favorable attitudes toward FDA regulations of newly deemed tobacco products. Support for FDA regulation of newly deemed products outweighed opposition. About half of smokers favored each of the 4 regulations, whereas only about 1 in 5 smokers opposed them. The remaining smokers were undecided. It is possible that since many smokers want to quit cigarettes,39 they would support regulations to prevent others from using other tobacco products. It is also possible that many smokers assumed that the FDA would regulate other tobacco products, such as cigars, e-cigarettes, and hookah, and therefore viewed regulations more favorably.

Research from public policy and agenda setting theory suggests that attitudes are an important factor in policy adoption, implementation, and effectiveness.6,7 For instance, in a review of the 1998 failed US Senate tobacco legislation, Blendon and Young concluded that lack of broad public support contributed to the legislation’s failure.40 Moreover, the tobacco industry can use public opposition to regulations to further delay implementation and marshal support among legislators concerned with limiting ‘individual freedom’.41,42 For these reasons, examining attitudes toward proposed or newly adopted regulations is important. While few studies have prospectively examined the relationship between attitudes and compliance with public health laws, some data suggest that how the public views laws or regulations may be associated with the extent to which they comply with regulations, taxes, and other legal requirements.43 Moreover, research from the US and UK suggests that there is a strong correlation between policy acceptability and perceived policy effectiveness.44 To increase the level of public support for new policies, tobacco control advocates could therefore use media campaigns as a population-level intervention. By emphasizing the need for regulation, the FDA’s role in regulating tobacco products, and the effectiveness of regulations, campaigns could attempt to make attitudes toward new FDA regulations more positive.12 Moreover, given that we found more than a quarter of smokers reported uncertainty regarding new FDA regulations, campaigns could focus on smokers who have not yet made up their minds as a way to increase favorable attitudes.

We also found that smokers with higher quit intentions and more negative beliefs about smokers had more favorable attitudes toward FDA regulations, a finding that is consistent with previous research.10 It is possible that smokers who would like to quit smoking cigarettes support regulations of other tobacco products as an additional measure to aid quit attempts. We cannot, however, determine the temporality of this association. At the very least, our findings suggest that media campaigns designed to increase public awareness or support about regulations could focus on smokers with low quit intentions. Notably, we found no difference in the proportion of favorable attitudes among users of e-cigarettes, hookah, and cigars compared to non-users of these products, which further suggests consistent support across products for these new regulations, independent of product use.

Smokers with income below the poverty line had less favorable attitudes toward FDA regulations and individuals with higher educational attainment had more favorable attitudes toward FDA regulations, suggesting the importance of including income and education as distinct control variables (rather than some combined “SES” variable) in future analyses.45 Finally, we found that exposure to e-cigarette advertising was associated with having more favorable attitudes toward most regulations. This finding stands in contrast with previous research in which higher exposure to advertising, media, and interpersonal discussion about e-cigarettes was associated with lower support for vaping regulations.31 It is possible that discrepancies occurred because other studies have looked at specific regulations (eg, policies to regulate vaping in certain venues) in the general public and our study looked at general regulations among smokers only. Future research could further explore the association between exposure to advertising and attitudes toward regulation.

Finally, in addition to federal regulation, states and localities can use favorable attitudes to enact and strengthen local tobacco control provisions. As of 2016, more than a dozen states and 500 localities have regulated e-cigarette use in existing smoke-free venues,46 more than a dozen states and 300 localities have regulated e-cigarette use in other venues,46 and several large cities—including Chicago and New York City—have regulated or prohibited the sale of flavored tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, cigars, and hookah.47 Our findings may suggest groups of individuals that local and state agencies may want to focus on to increase favorable attitudes toward regulations.

Limitations

Strengths of our study include our diverse sample of adult smokers. However, limitations include that we cannot determine the temporality of associations; our measures of FDA regulations did not include specific examples of regulations (eg, banning use, regulating sale) or what regulation means; and we did not assess awareness of current FDA regulations. Additionally, we collected data using a convenience sample of smokers for a randomized clinical trial, which may limit the generalizability of findings to smokers more broadly. Moreover, attitudes toward the deeming rule among non-smokers and after the implementation of the rule remain unknown. Despite these limitations, our study provides new data about attitudes toward FDA regulations of newly deemed tobacco products among US smokers. Future research could be used to explore more in-depth perceptions of specific regulations, policy support among non-smokers and former smokers, and what “regulation” may mean to different people.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION

Implementation of FDA regulations of newly deemed tobacco products is ongoing. Our findings suggest several areas of particular interest for tobacco regulatory science. First, about half of smokers supported FDA regulation of e-cigarettes, cigars, and hookah. Support is likely to be even higher among non-smokers.10,23,31 This high level of public support may facilitate compliance with and enforcement of the FDA’s new regulatory measures,12–16 such as reporting adverse experiences or product violations,48 and effectiveness of the FDA’s new regulatory measures, such as noticing health warnings on newly deemed tobacco products.49 Continued surveillance of public attitudes will allow FDA to tailor messaging about new policies.

However, some smokers were undecided about or opposed stronger regulations. As implementation and enforcement of FDA regulations continues, stronger educational campaigns that encourage compliance with existing and new regulations may be necessary. Such campaigns could emphasize the rationale and potential benefits of regulation and define FDA’s role in regulation.12 These campaigns could focus on smokers who have not made up their minds about regulations (~28% in our study) or smokers who opposed regulation (~22%). Such campaigns would have the potential to increase favorable attitudes toward regulation, and they could also help normalize policy change and regulation of tobacco products to counter marketing and arguments from the tobacco industry.

Finally, tobacco control regulations continue to occur locally and in states, outside of federal regulations. Community organizations and tobacco control advocates in states can build on the high level of support we found in our study to enact and strengthen tobacco control provisions for e-cigarettes, cigars, and hookah. Historically, grassroots community efforts have succeeded in encouraging adoption of some of the strongest and most innovative tobacco control policies, which can then pave the way for state and federal adoption.50 By using well-known strategies, such as allowing constituents to engage with policymakers or capitalizing on relationships with retailers,17 local communities can adopt innovative regulations of new tobacco products, such as flavor or advertising restrictions to prevent youth initiation. Moreover, community organizations and tobacco control advocates can even seek support from smokers who favor regulation to influence legislators’ perceptions of constituent support.6 In the meantime, while implementation of FDA regulation of newly deemed tobacco products continues, further research is needed on what types of regulations smokers and non-smokers favor, how they define regulation, and the role of the FDA in regulation.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30CA016086. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

T32-CA057726 from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health supported MGH’s time writing the paper.

Grant number P50 CA180907 from the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) supported SDK, AMS, and AOG’s time spent writing the paper. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Tara Queen for her help in thoughtfully reviewing the statistical analysis and study results.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board approved study procedures, and participants provided their written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Sarah D. Kowitt, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Adam O. Goldstein, Department of Family Medicine, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Allison M. Schmidt, Innovation, Research, and Training, Durham, NC.

Marissa G. Hall, Cancer Control Education Program, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Noel T. Brewer, Department of Health Behavior, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; regulations on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Fed Regist. 2016;79(80):1–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health Law Center. Federal regulation of tobacco: impact on state and local authority (on-line) [Accessed August 4, 2016]; Available at: http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-fda-impact.pdf.

- 3.Public Health Law Center at Mitchell Hamline School of Law. U.S. e-cigarette regulations - 50 state review (on-line) [Accessed August 4, 2016]; Available at: http://publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review.

- 4.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Regulating hookah and water pipe smoking (on-line) [Accessed August 4, 2016]; Available at: http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-reg-hookah-2016.pdf.

- 5.Convenience Store News. Lawsuits accumulating against FDA's deeming rule (on-line) [Accessed August 4, 2016]; Available at: http://www.csnews.com/product-categories/tobacco/lawsuits-accumulating-against-fdas-deeming-rule.

- 6.Flynn BS, Goldstein AO, Solomon LJ, et al. Predictors of state legislators' intentions to vote for cigarette tax increases. Prev Med. 1998;27(2):157–165. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies. Vol. 13. Geneva, Switzerland: IARC Press; 2009. Chapter 5: Public attitudes towards smoke-free policies – including compliance with policies. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unger JB, Rohrbach LA, Howard KA, et al. Attitudes toward anti-tobacco policy among California youth: associations with smoking status, psychosocial variables and advocacy actions. Health Educ Res. 1999 Dec;14(6):751–763. doi: 10.1093/her/14.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose SW, Emery SL, Ennett S, McNaughton Reyes HL, Scott JC, Ribisl KM. Public Support for Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act Point-of-Sale Provisions: Results of a National Study. Am J Public Health. 2015 Oct;105(10):e60–67. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Wenter D. Media advocacy, tobacco control policy change and teen smoking in Florida. Tob Control. 2007 Feb;16(1):47–52. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thrasher JF, Huang L, Perez-Hernandez R, et al. Evaluation of a social marketing campaign to support Mexico City's comprehensive smoke-free law. Am J Public Health. 2011 Feb;101(2):328–335. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.189704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thrasher JF, Boado M, Sebrie EM, Bianco E. Smoke-free policies and the social acceptability of smoking in Uruguay and Mexico: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009 Jun;11(6):591–599. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sebrie EM, Schoj V, Glantz SA. Smokefree environments in Latin America: on the road to real change? Prev Control. 2008 Jan 01;3(1):21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.precon.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong GT, Hyland A, Borland R, et al. Reductions in tobacco smoke pollution and increases in support for smoke-free public places following the implementation of comprehensive smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland: findings from the ITC Ireland/UK Survey. Tob Control. 2006 Jun;15(Suppl 3):iii51–58. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Compliance and Enforcement. Enforcement action plan for promotion and advertising restrictions (on-line) [Accessed April 25, 2017]; Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/RulesRegulationsGuidance/UCM227882.pdf.

- 17.Moreland-Russell S, Combs T, Schroth K, Luke D. Success in the city: the road to implementation of Tobacco 21 and Sensible Tobacco Enforcement in New York City. Tob Control. 2016 Oct;25(Suppl 1):i6–i9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Utah Tobacco Prevention and Control Program. Utah secondhand smoke policy implementation guide: multiple-unit housing (on-line) [Accessed April 25, 2017]; Available at: http://www.tobaccofreeutah.org/pdfs/shsoutdoor.pdf.

- 19.Figueroa HL, Lynch A, Totura C, Wolfersteig W. Maricopa county policy assessment: smoke-free parks (on-line) [Accessed April 21, 2017]; Available at: http://azdhs.gov/documents/prevention/tobacco-chronic-disease/tobacco-free-az/reports/smoke-free-parks-policy-assessment.pdf.

- 20.Sparks M, Bell RA, Sparks A, Sutfin EL. Creating a healthier college campus: a comprehensive manual for implementing tobacco-free policies (on-line) [Accessed April 21, 2017]; Available at: http://www.wakehealth.edu/uploadedFiles/User_Content/Research/Departments/Public_Health_Sciences/Tobacco_Free_Colleges/Tobacco-Free Manual_Web7.pdf.

- 21.Hall MG, Sheeran P, Noar SM, et al. Reactance to health warnings scale: development and validation. Ann Behav Med. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9799-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall MG, Sheeran P, Noar SM, et al. A brief measure of reactance to health warnings. J Behav Med. 2017;40(3):520–9. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9821-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winickoff JP, McMillen RC, Vallone DM, et al. US attitudes about banning menthol in cigarettes: results from a nationally representative survey. Am J Public Health. 2011 Jul;101(7):1234–1236. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson JL, Abrams DB, Niaura RS, et al. A ban on menthol cigarettes: impact on public opinion and smokers' intention to quit. Am J Public Health. 2012 Nov;102(11):e107–114. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unger JB, Barker D, Baezconde-Garbanati L, et al. Support for electronic cigarette regulations among California voters. Tob Control. 2017 May;26(3):334–337. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan AS, Lee C-j, Bigman CA. Public support for selected e-cigarette regulations and associations with overall information exposure and contradictory information exposure about e-cigarettes: Findings from a national survey of US adults. Prev Med. 2015;81:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewer NT, Hall MG, Noar SM, et al. Effect of pictorial cigarette pack warnings on changes in smoking behavior: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jul 1;176(7):905–912. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reliability and validity of self-reported smoking in an anonymous online survey with young adults. Health Psychol. 2011 Nov;30(6):693–701. doi: 10.1037/a0023443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein WM, Zajac LE, Monin MM. Worry as a moderator of the association between risk perceptions and quitting intentions in young adult and adult smokers. Ann Behav Med. 2009 Dec;38(3):256–261. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen JA, Davis KC, Kamyab K, Farrelly MC. Exploring the potential for a mass media campaign to influence support for a ban on tobacco promotion at the point of sale. Health Educ Res. 2015 Feb;30(1):87–97. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan AS, Bigman CA, Sanders-Jackson A. Sociodemographic correlates of self-reported exposure to e-cigarette communications and its association with public support for smoke-free and vape-free policies: results from a national survey of US adults. Tob Control. 2015 Nov;24(6):574–581. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Instruments for wave 2 of the PATH study (on-line) [Accessed January 25, 2017]; Available at: https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/PRAViewIC?ref_nbr=201407-0925-004&icID=212557.

- 33.McCool JP, Cameron L, Petrie K. Stereotyping the smoker: adolescents' appraisals of smokers in film. Tob Control. 2004 Sep;13(3):308–314. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibbons FX, Eggleston TJ. Smoker networks and the" typical smoker": a prospective analysis of smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1996;15(6):469. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for starting and stopping electronic cigarette use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):10345–10361. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111010345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCool J, Cameron LD, Robinson E. Do parents have any influence over how young people appraise tobacco images in the media? J Adolesc Health. 2011 Feb;48(2):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong S-M, Faedda S. Refinement of the Hong psychological reactance scale. Educ Psychol Meas. 1996;56(1):173–182. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jonason PK, Knowles HM. A unidimensional measure of Hong's psychological reactance scale. Psychol Rep. 2006 Apr;98(2):569–579. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.2.569-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blendon RJ, Young JT. The public and the comprehensive tobacco bill. JAMA. 1998 Oct 14;280(14):1279–1284. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myers E. Manipulation of Public Opinion by the Tobacco Industry: Past, Present, and Future, The. J. Health Care L. & Pol'y. 1998;2:79. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katz JE. Individual rights advocacy in tobacco control policies: an assessment and recommendation. Tob Control. 2005;14(suppl 2):ii31–ii37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morain S, Mello MM. Survey finds public support for legal interventions directed at health behavior to fight noncommunicable disease. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Mar;32(3):486–496. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrescu DC, Hollands GJ, Couturier DL, et al. Public Acceptability in the UK and USA of nudging to reduce obesity: the example of reducing sugar-sweetened beverages consumption. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0155995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(2):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Nonsmokers' Rights Foundation. States and municipalities with laws regulating use of electronic cigarettes (on-line) [Accessed January 9, 2017]; Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwi096vgj7bRAhUDOSYKHZ_yAigQFggaMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fno-smoke.org%2Fpdf%2Fecigslaws.pdf&usg=AFQjCNHbm0ufSipSai0xq1eKnaS4vo3Zdg&sig2=5-IGG2uM_59pNEwyILpWsA&bvm=bv.143423383,d.eWE.

- 47.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Regulating flavored tobacco products (on-line) [Accessed January 9, 2017]; Available at: http://publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-guide-regflavoredtobaccoprods-2014.pdf.

- 48.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Vaporizers, e-cigarettes, and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) (on-line) [Accessed June 7, 2017]; Available at: https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ProductsIngredientsComponents/ucm456610.htm#reporting.

- 49.Li Z, Marshall TE, Fong GT, et al. Noticing cigarette health warnings and support for new health warnings among non-smokers in China: findings from the International Tobacco Control project (ITC) China survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):476. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4397-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tobacco Control Legal Consortium. Preemption: the biggest challenge to tobacco control (on-line) [Accessed June 3, 2017]; Available at: http://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/resources/tclc-fs-preemption-tobacco-control-challenge-2014.pdf.